It was William’s birthday, but, in spite of that, his spirit was gloomy and overcast. He hadn’t got Jumble, his beloved mongrel, and a birthday without Jumble was, in William’s eyes, a hollow mockery of a birthday.

Jumble had hurt his foot in a rabbit trap, and had been treated for it at home, till William’s well-meaning but mistaken ministrations had caused the vet to advise Jumble’s removal to his own establishment.

William had indignantly protested, but his family was adamant. And when the question of his birthday celebration was broached, feeling was still high on both sides.

“I’d like a dog for my birthday present,” said William.

“You’ve got a dog,” said his mother.

“I shan’t have when you an’ that man have killed it between you,” said William. “He puts on their bandages so tight that their calculations stop flowin’ an’ that’s jus’ the same as stranglin’ ’em.”

“Nonsense, William!”

“Anyway, I want a dog for my birthday present. I’m sick of not havin’ a dog. I want another dog. I want two more dogs.”

“Nonsense! Of course you can’t have another dog.”

“I said two more dogs.”

“You can’t have two more dogs.”

“Well, anyway, I needn’t go to the dancing-class on my birthday.”

The dancing-class was at present the bane of William’s life. It took place on Wednesday afternoons – William’s half-holiday – and it was an ever-present and burning grievance to him.

He was looking forward to his birthday chiefly because he took for granted that he would be given a holiday from the dancing-class. But it turned out that there, too, Fate was against him.

Of course he must go to the dancing-class, said Mrs Brown. It was only an hour, and it was a most expensive course, and she’d promised that he shouldn’t miss a single lesson because Mrs Beauchamp said that he was very slow and clumsy and she really hadn’t wanted to take him.

To William it seemed the worst that could possibly happen to him. But it wasn’t. When he heard that Ethel’s admirer, Mr Dewar, was coming to tea on his birthday, his indignation rose to boiling point.

“But it’s my birthday. I don’t want him here on my birthday.”

William had a deeply rooted objection to Mr Dewar. Mr Dewar had an off-hand, facetious manner which William had disliked from his first meeting with him.

William awoke on the morning of his birthday, still in a mood of unmelting resentment.

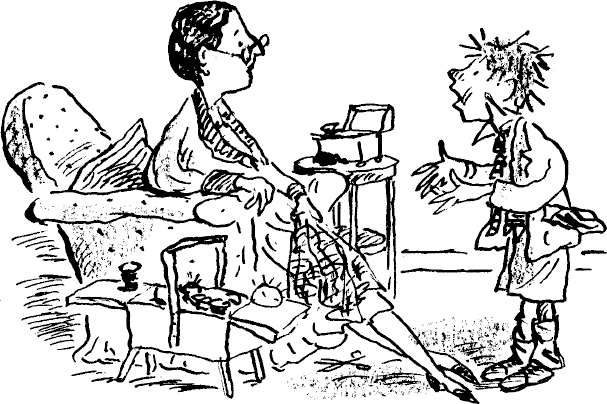

He went downstairs morosely to receive his presents.

His mother’s present to him was a dozen new handkerchiefs with his initials upon each, his father’s a new leather pencil-case. William thanked them with a manner of cynical aloofness of which he was rather proud.

“Now, William,” said his mother anxiously, “you’ll go to the dancing-class nicely this afternoon, won’t you?”

“I’ll go the way I gen’rally go to things. I’ve only got one way of goin’ anywhere. I don’t know whether it’s nice or not.”

This brilliant repartee cheered him considerably. But still: no Jumble; a dancing class; that man to tea. Gloom closed over him again. Mrs Brown was still looking at him anxiously. She had an uneasy suspicion that he meant to play truant from the dancing-class.

When she saw him in his hat and coat after lunch she said again, “William, you are going to the dancing-class, aren’t you?”

William walked past her with a short laugh that was wild and reckless and daredevil and bitter and sardonic. It was, in short, a very good laugh, and he was proud of it.

Then he swaggered down the drive, and very ostentatiously turned off in the opposite direction to the direction of his dancing-class. He walked on slowly for some time and then turned and retraced his steps with furtive swiftness.

To do so he had to pass the gate of his home, but he meant to do this in the ditch so that his mother, who might be still anxiously watching the road for the reassuring sight of his return, should be denied the satisfaction of it.

He could not resist, however, peeping cautiously out of the ditch when he reached the gate, to see if she were watching for him. There was no sign of her, but there was something else that made William rise to his feet, his eyes and mouth wide open with amazement.

There, tied to a tree in the drive near the front door, were two young collies, little more than pups. Two dogs. He’d asked his family for two dogs and here they were. Two dogs. He could hardly believe his eyes.

His heart swelled with gratitude and affection for his family. How he’d misjudged them! Thinking they didn’t care two pins about his birthday, and here they’d got him the two dogs he’d asked for as a surprise, without saying anything to him about it. Just put them there for him to find.

His heart still swelling with love and gratitude, he went up the drive. The church clock struck the hour. He’d only just be in time for the dancing-class now, even if he ran all the way.

His mother had wanted him to be in time for the dancing-class and the sight of the two dogs had touched his heart so deeply that he wanted to do something in return, to please his mother.

He’d hurry off to the dancing-class at once, and wait till he came back to thank them for the dogs.

He stooped down, undid the two leads from the tree, and ran off again down the drive. The two dogs leapt joyfully beside him.

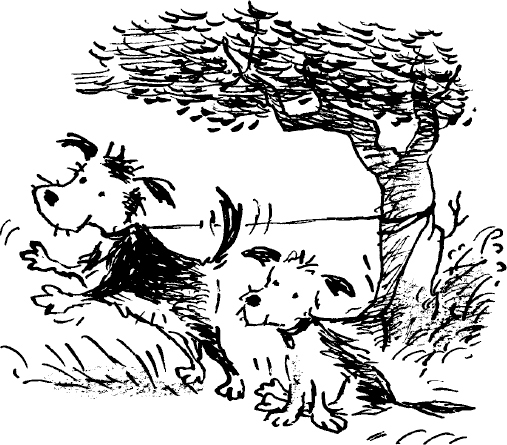

The smaller collie began to direct his energies to burrowing in the ditches, and the larger one to squeezing through the hedge, where he found himself, to his surprise, in a field of sheep.

He did not know that they were sheep. It was his first day in the country. He had only that morning left a London shop. But dim instincts began to stir in him.

William, watching with mingled consternation and delight, saw him round up the sheep in the field and begin to drive them pell-mell through the hedge into the road; then, hurrying, snapping, barking, drive the whole jostling perturbed flock of them down the road towards William’s house.

William stood and watched the proceedings. The delight it afforded him was tempered with apprehension.

The collie had now made his way into a third field, in search of recruits, while his main army waited for him meekly in the road. William hastily decided to dissociate himself from the proceedings entirely. Better to let one of his dogs go than risk losing both . . .

He hurried on to the dancing-class. Near the front door he tied the collie to a tree with the lead, and entered a room where a lot of little boys – most of whom William disliked intensely – were brushing their hair and changing their shoes.

At last a tinkly little bell rang, and they made their way to the large room where the dancing-class was held. From an opposite door was issuing a bevy of little girls, dressed in fairy-like frills, with white socks and dancing-shoes.

There followed an attendant army of mothers and nurses who had been divesting them of stockings and shoes and outdoor garments.

William greeted these fairy-like beings with his most hideous grimace. The one he disliked most of all (a haughty beauty with auburn curls) was given him as a partner.

“Need I have William?” she pleaded. “He’s so awful.”

“I’m not,” said William. “I’m no more awful than her.”

“Have him for a few minutes, dear,” said Mrs Beauchamp, who was tall and majestic and almost incredibly sinuous, “and then I’ll let you have someone else.”

The dancing-class proceeded on its normal course. William glanced at the clock and sighed. Only five minutes gone. A whole hour of it – and on his birthday. His birthday. Even the thought of his two new dogs did not quite wipe out that grievance.

“Please may I stop having William now? He’s doing the steps all wrong.”

William defended himself with spirit.

“I’m doin’ ’em right. It’s her what’s doin’ ’em wrong.”

Mrs Beauchamp stopped them and gave William another partner – a little girl with untidy hair and a roguish smile. She was a partner more to William’s liking, and the dance developed into a competition as to who could tread more often on the other’s feet.

It was, of course, a pastime unworthy of a famous Indian Chief, but it was better than dancing. He confided in her.

“It’s my birthday today, and I’ve had two dogs given me.”

“Oo! Lucky!”

“An’ I’ve got one already, so that makes three. Three dogs I’ve got.”

“Oo, I say! Have you got ’em here?”

“I only brought one. It’s in the garden tied to a tree near the door.”

“Oo, I’m goin’ to look at it when we get round to the window!”

They edged to the window, and the little girl glanced out with interest, and stood, suddenly paralysed with horror, her mouth and eyes wide open. But almost immediately her vocal powers returned to her.

“Look!” she said. “Oh, look!”

They all crowded to the window.

The collie had escaped from his lead and found his way into the little girls’ dressing-room.

There he had collected the stockings, shoes, and navy-blue knickers that lay about and brought them all out on to the lawn, where he was happily engaged in worrying them.

Remnants lay everywhere about him. He was tossing up into the air one leg of a pair of navy-blue knickers. Around him the air was thick with wool and fluff. Bits of unravelled stockings, with here and there a dismembered hat, lay about on the lawn in glorious confusion.

He was having the time of his life.

After a moment’s frozen horror the whole dancing-class – little girls, little boys, nurses, mothers, and dancing-mistress – surged out on to the lawn.

The collie saw them coming and leapt up playfully, half a pair of knickers hanging out of one corner of his mouth, and a stocking out of the other.

They bore down upon him in a crowd. He wagged his tail in delight. All these people coming to play with him!

He entered into the spirit of the game at once and leapt off to the shrubbery, followed by all these jolly people. A glorious game! The best fun he’d had for weeks . . .

Meanwhile William was making his way quietly homeward. They’d say it was all his fault, of course, but he’d learnt by experience that it was best to get as far as possible away from the scene of a crime . . .

He turned the bend in the road that brought his own house in sight, and there he stood as if turned suddenly to stone. He’d forgotten the other dog.

The front garden was a sea of sheep. They covered drive, grass and flower beds. They even stood on the steps that led to the front door. The overflow filled the road outside.

Behind them was the other collie pup, running to and fro, crowding them up still more closely, pursuing truants and bringing them back to the fold.

Having collected the sheep, his instinct had told him to bring them to his master. His master was, of course, the man who had brought him from the shop, not the boy who had taken him for a walk. His master was in this house. He had brought the sheep to his master . . .

His master was, in fact, with Ethel in the drawing-room. Mrs Brown was out and was not expected back till tea-time.

Mr Dewar had not yet told Ethel about the two collies he had brought for her. She’d said last week that she “adored” collies, and he’d decided to bring her a couple of them. He meant to introduce the subject quite carelessly, at the right moment.

And so, when she told him that he seemed to understand her better than any other man she’d ever met (she said this to all her admirers in turn), he said to her quite casually, “Oh! By the way, I forgot to mention it but I just bought a little present – or rather presents – for you this afternoon. They’re in the drive.”

Ethel’s face lit up with pleasure and interest.

“Oh, how perfectly sweet of you,” she said.

“Have a look at them, and see if you like them.”

She walked over to the window. He remained in his armchair, watching the back of her Botticelli neck, lounging at his ease – the gracious, all-providing male. She looked out. Sheep – hundreds and thousands of sheep – filled the drive, the lawn, the steps, the road outside.

“Well,” said Mr Dewar, “do you like them?”

She raised a hand to her head.

“What are they for?” she said faintly.

“Pets,” said Mr Dewar.

“Pets!” she screamed. “I’ve nowhere to keep them. I’ve nothing to feed them on.”

“Oh, they only want a few dog biscuits.”

“Dog biscuits?”

Ethel stared at them wildly for another second, then collapsed on to the nearest chair in hysterics.

Mrs Brown had returned home. Mrs Brown had had literally to fight her way to the front door through a tightly packed mass of sheep.

Mr Dewar was wildly apologetic. He couldn’t think what had happened. He couldn’t think where the sheep had come from.

The other dog arrived at the same moment as a crowd of indignant farmers demanding their sheep. It still had a knicker hanging out of one corner of its mouth and a stocking out of the other.

William was nowhere to be seen.

William came home about half an hour later. There were no signs of Mr Dewar, or the dogs, or the sheep. Ethel and Mrs Brown were in the drawing-room.

“I shall never speak to him again,” Ethel was saying. “I don’t care whether it was his fault or not. I’ve told him never to come to the house again.”

“I don’t think he’d dare to when your father’s seen the state the grass is in. It looks like a ploughed field.”

“As if I’d want hundreds of sheep like that,” said Ethel, still confusing what Mr Dewar had meant to do with what he had actually done. “Pets indeed!”

“And Mrs Beauchamp’s just rung up about the other dog,” went on Mrs Brown. “It evidently followed William to the dancing-class and tore up some stockings and things there. I don’t see how she can blame us for that. She really was very rude about it. I don’t think I shall let William go to any more of her dancing-classes.”

William sat listening with an expressionless face, but his heart was singing within him. No more dancing classes . . . that man never coming to the house any more. A glorious birthday – except for one thing, of course.

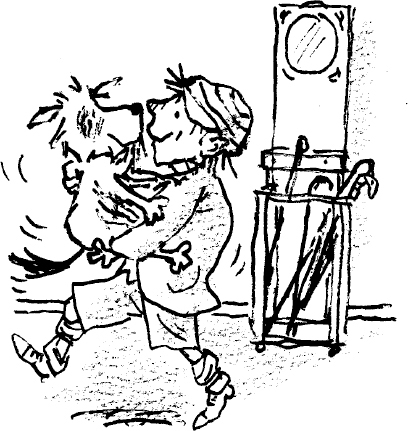

But just then the housemaid came into the room.

“Please, ’m, it’s the man from the vet with Master William’s dog. He says he’s quite all right now.”

William leapt from the room, and he and Jumble fell upon each other ecstatically in the hall. The minute he saw Jumble, William knew that he could never have endured to have any other dog.

“I’ll take him for a little walk. I bet he wants one.”

The joy of walking along the road again, with his beloved Jumble at his heels. William’s heart was full of dreamy content.

He’d got Jumble back. That man was never coming to the house any more.

He wasn’t going to any more dancing-classes.

It was the nicest birthday he’d ever had in his life.