13

THE Saint Stephen’s Episcopal Church basement smelled of cabbage, which might have explained the puckered-up face of Reverend Jonas P. Mudge. “And what exactly is the nature of your business with Mr. Hanscombe?” he sniffed, peering through thick glasses at Bitsy, Max, and Alex. “We are quite busy here, and—”

From behind him a voice called out, “Let them in, Jonas, fiddledeedee, lunch is over and I’m a free man.”

“As you wish, Nigel,” the reverend said, stepping aside.

Down a dim, narrow corridor walked a bent but quick-moving silhouette. As he emerged into the light of the open door, he smiled. One eye drooped, but the other shone as brightly as in the photo of his younger self. Looking from Max to Alex, the eye quickly became moist with emotion. “Glorious,” he said. “So my instincts about you were correct. Please. Come in, children. Reverend, we shall be in my office.”

He led them into a small side office with no windows. Flicking on a light, Nigel gestured to the corner, where several folded metal chairs were propped against the bare wall. Max, Alex, and Bitsy unfolded three of them as the old man sat on a battered wooden desk. With a smile, he thrust out his arms joyously. “What a banner day this is! How utterly enchanting to see you again—”

“We need facts,” Max said. “Are you really who you say you are—a relative of Gaston, the nephew who shot Jules Verne?”

Nigel’s face flinched with surprise. He focused on Max, his good eye steel-gray and steady. “Well, we don’t stand on ceremony, do we? The facts. Yes, Gaston is my ancestor.”

“Did you know about the list that Queasly had saved?” Max pressed.

“A list?” Nigel replied. “I thought Gaston had written a rather long work.”

“I think that’s probably lost,” Max said. “The club never got it. But Gaston made a short summary. You didn’t know that?”

“No.”

“So you didn’t know where it was hidden?”

“No. Did you find it?”

“I’m asking the questions,” Max said.

Nigel let out a high-pitched squeak of a laugh. “You drive a hard bargain, young man. I like that.”

“Did you know you gave us a code that only worked on one page?” Max pressed on.

“Not exactly. I don’t really know how the codes work.”

“Do you have any other code keys?”

Nigel’s eyebrows shot way up. “Well, well . . . I believe I do.” He nearly floated off his desk, spinning around to sit in a chair. From a file cabinet he pulled out a metal box of his own and spun a combination lock to reveal another metal box, which he unlocked with a key. Inside that was a third box guarded by a finger pad, and from that he pulled out an unmarked manila envelope. His fingers were shaking. “You will forgive my nerves. I had given up hope, and as I have no children, these documents would have died with me.”

He spilled out a small stack of papers, each about the size of an index card. Max recognized the one on top. “V minus two, C plus one,” he said. “We used that one already. It decoded the first page.”

“Ah,” Nigel said. “That would explain why the card is labeled on the back with a 1. Code one for page one.”

“Splendid!” Bitsy said. “Where is the one for page two?”

Max quickly found the card labeled 2, then turned it to the front.

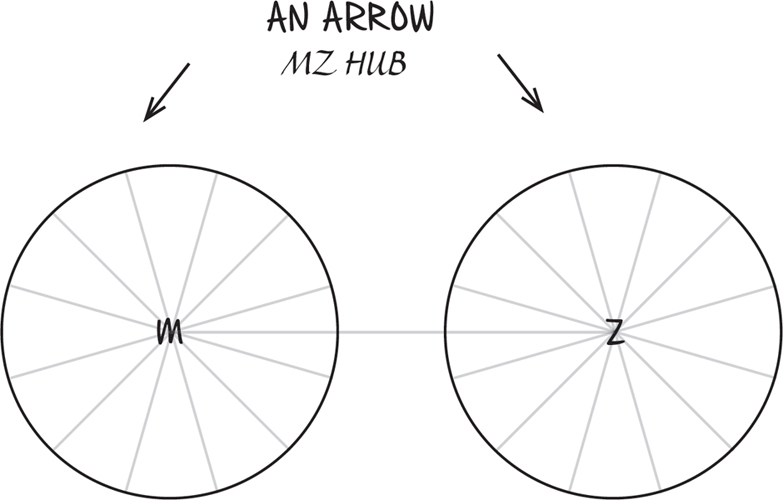

“What on earth—?” he murmured.

“Wagon wheels,” Bitsy said. “How . . . eccentric.”

Alex groaned. “How is this supposed to help us?”

“This one,” Nigel said, “has remained a mystery.”

Max drummed his fingers on the table. They let out a dull pudududum . . . pudududum . . . “I’m not getting why there’s a drawing of wheels. This is a code. A code is about letters.”

“Yes, lad, I have looked at this many times,” Nigel said. “I can only assume that the text on top is crucial. It refers to ‘an arrow’ . . .”

“But there are two arrows,” Bitsy said.

“It also says ‘MZ hub’—whatever MZ means—and there are two hubs,” Max said.

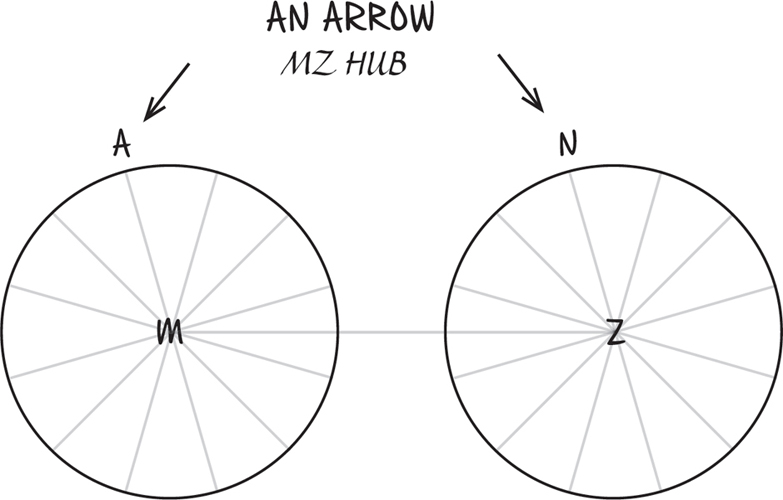

“Aren’t M and Z random letters?” Alex said. “Two letters, two hubs? Maybe that’s a start. You put the letters into the hubs?”

“Why would you do that?” Bitsy asked.

“I don’t know, for some crazy, code-y reason?” Alex said.

Nigel opened a drawer and pulled out a pencil. “Be my guest.”

Max took it and wrote carefully on the card:

Max stared at it a moment. “So what does ‘an arrow’ mean?”

Pudududum . . . pudududum . . .

“Will you stop that?” Alex snapped.

“Perhaps the arrows indicate which way to spin the wheels?” Bitsy suggested.

“This is a code, not a toy,” Nigel said.

Max slapped his hand down on the table. “Maybe it’s not ‘an arrow’! M and Z are two random letters, right? Two letters, followed by their location—‘hub.’ So maybe A and N are meant to be two random letters too. Then that top line could mean ‘A, N arrow.’”

“So if we put the M and the Z in the hubs,” Alex piped up, “we can put A and N where the arrows are!”

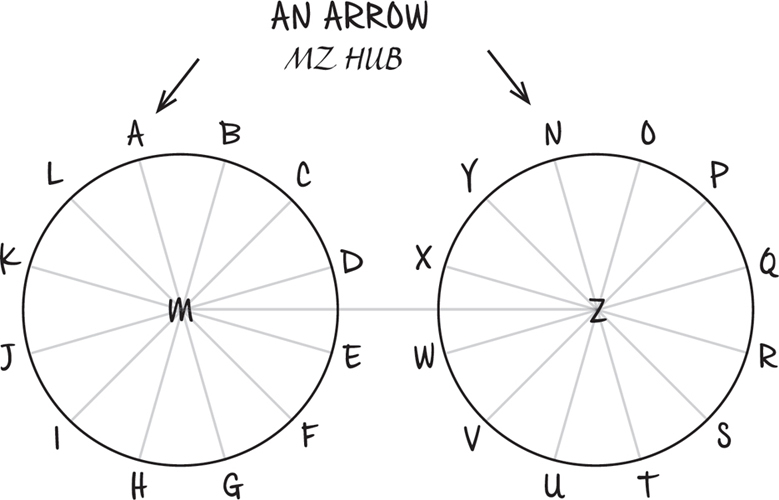

“Clever!” Bitsy said. “Looks like the circles are dividing the alphabet. The first one is A through M, and the second circle is N through Z.”

“Where do the other letters go?” Max murmured. Pudududum . . . pudududum . . .

Alex smacked her hand down over Max’s. “Max, there are twelve lines in each circle. M and Z are in the middle, so there are twenty-four letters left. So if you had a letter at each end, they’d all fit!”

Max nodded. “The first half of the alphabet in the first circle, the second half in the second circle . . . letters arranged around the circumference, like numbers on an analog clock . . .”

He quickly filled in more letters:

Max jumped up from the table. “Y-y-y-yes! Got it!”

“It’s . . . lovely,” Nigel said. “But what does it mean?”

Alex peered at it. “I’m thinking it’s a substitution. You swap each letter with the letter on the opposite side of the circle, connected by the line—so A for G and G for A. Same with B and H, C and I, and so on. The ones in the middle, M and Z, swap with each other.”

Bitsy leaned over the desk, pulling out page 2.

Hkcta nbk Hgyci Yozzgncut ul Krnxguxjctgxcfs Iuzvfcignkj Kpktny, Fkgjcta nu nbk Jcyiupkxs ul g Yohyngtik ul Otyvkgeghfk Xkpufoncutgxs Czvuxngtik nu nbk Bozgt Xgik

Yohzcnnkj hs Agynut nbk Zgatclciktn

Hkact qcnb Cycy bcvvoxcy, ghupk gff gtj qcnbuon qbcib tunbcta igt bgvvkt.

Gjj nbk ygfohxcuoy gtj igngfsncigffs zgxpkfuoy kllkiny ovut nbcy yohyngtik, jkxcpkj lxuz nbk luffuqcta qgnkx yuoxiky:

* Vxkykxpkj qcnb nbk nctinoxk ul iucf joyn lxuz nbk Eumbcz Xcpkx

* Krnxginkj lxuz nbk xkj iugn ul nbk gticktn qkn xcpkx buxyk lxuz nbk yuoxik ul nbk Xcpkx Ynsr

* Ngekt lxuz g aufl hgff’y iktnkx ct nbk lgn zuotngcty ul Zkrciu

* Jkxcpkj lxuz nbk hfgie yzkgx ul knkxtcns lxuz Gxzgtju ul Egnbzgtjo

* Xkyiokj lxuz g bun igpk ct nbk quxfj’y iufjkyn fgtj zgyy

“This will take forever,” Bitsy said. “You have to replace every single letter?”

“Ugh,” Alex groaned.

“Can we have a bite to eat first?” Nigel asked.

But Max was already writing. “Eat all you want. I’m working.”