ON THE ACCOUNT

WWoodes Rogers’s appointment as captain general and governor in chief of the entire Bahamian archipelago gave him vast authority, but nowhere near enough warships (two) or men (a hundred soldiers) to take the place away from the thousand or so buccaneers who had taken root and refuge there. Not if they chose to resist.

Nor would Rogers have the advantage of surprise. Months before his planned arrival to take up his post at Nassau, a proclamation had been dispatched there announcing his advent, and that he would come with the king’s pardon for all who were willing to give up their wicked ways.

The brotherhood’s response at Nassau was to seize the ship bearing the message, and to convene a council that brought in the biggest family gathering of brethren since Morgan’s time. Their sloops and schooners sailed in from the Mexican Gulf to Newfoundland. The big question for all was whether to resist or take the pardon. A fight would mean a declaration of independence from England and its empire, with inevitable and untold consequences. It was very tempting to accept, instead, a royal pardon that would forgive everything one had done, as long as one didn’t do it again. In the end, that was the decision made by the majority, and Rogers’s arrival was unopposed, except for one last, impudent broadside from some of those who chose to escape and carry on with their ways.

To Rogers’s relief, when he stepped ashore, he was saluted by several hundred scruffy but loyal subjects, and from them he immediately began forming a militia to enforce and protect his new government. He also commissioned some of his ex-buccaneers to go out and capture their unrepentant former friends for trial and hanging, which they did.

Rogers had won by dividing the English buccaneer community between those who didn’t want to declare war on their own flag, and those whose war was with the entire abusive (to poor sailors) system of the maritime world – flags and letters of marque be damned. These sailed “on the account,” as it was called, meaning on their own account, a state of affairs described most eloquently by Captain Sam Bellamy.

Working the New England coast in his thirty-gun, oared frigate Whydah Gally, Bellamy came across a sloop in the middle of a dense fog. The master of the sloop, seeing a warship appear out of the mist, hailed it through his speaking trumpet: “Where are you from?”

“The seas,” answered Bellamy, promptly seizing the sloop. Customarily, the buccaneers tried to enlist any of their prisoners who wanted to be as free as themselves. As Bellamy put it to the sloop’s master when he turned down the invitation:

Damn ye, you are a sneaking puppy, and so are all those who will submit to be governed by laws which rich men have made for their own security, for the cowardly whelps have not the courage otherwise to defend what they get by their knavery. But damn ye all together. Damn them for a pack of crafty rascals, and you, who serve them, for a parcel of hen-hearted numbskulls. They vilify us, the scoundrels do, when there is only one difference, they rob under the cover of law, forsooth, and we plunder the rich under the protection of our own courage.

All of Bellamy’s captives were let go safe and sound, and off sailed Whydah back into the mists.

Like others of the brethren, Bellamy used the outports of northeastern America, from Maine to Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, to recruit willing hands. As well, they could tuck in to a remote cove for refitting, rest, recreation, and music. Musicians were much prized, and were given an increased share of the spoils. Bellamy even staged theatrical dramas on his quarterdeck. His luck ran out off Cape Cod, where his ship drove aground in a gale, drowning him and all of his crew except for eight, who survived the wreck to be tried and hanged in Boston. Silver pieces of eight from Whydah’s treasure still wash ashore off Cape Cod.

With no more major ports of refuge willing to take them, the freelance brethren still operating had to make a choice between sailing big, full-rigged ships, like Whydah, or smaller vessels, such as sloops. Besides firepower, the advantage of a big ship was its better ability to make long voyages. Its drawbacks included some disadvantage in chasing smaller craft, particularly in shoal waters, where a big corsair could be outmaneuvered by a clever smaller quarry. Also, with no adequate ports available for supply and repair, a big ship had to be replaced eventually by some fresher prize taken at sea.

In the Americas, the brotherhood largely got rid of bigger warships, with their bigger problems, adopting in their place the smaller, more versatile single-masted sloops used by the Bermudians and Bahamians. These could not be heavily enough gunned to fight the Royal Navy’s ships, but their swivel cannon, light carriage guns, and big crews were more than a match for the average merchant vessel.

PPerhaps Nassau’s most infamous pirate of all was William Teach, or Blackbeard, as he is known to history. He sailed for a while with a forty-gun ship named Queen Anne’s Revenge, but abandoned her (and her crew) in favor of a ten-gun sloop, which he then used as a private, armed yacht, cruising the Carolina coasts and raiding east to Bermuda.

Teach was a big man, and a formidable competitor, worthy of his legend, but his main talent was getting what he wanted by invoking terror rather than fighting. By a contemporary account:

Captain Teach assumed the cognomen of Blackbeard from that large quantity of hair, which, like a frightful meteor, covered his whole face and frightened America more than any comet that had appeared there a long time. This beard was black, which he suffered to grow of an extravagant length. …. He was accustomed to twist it with ribbons, in small tails. …. In time of action he wore a sling over his shoulders with three brace of pistols and stuck lighted matches under his hat, which … his eyes naturally looking fierce and wild, made him altogether an idea of a fury, from hell.

Blackbeard’s terror tactics worked very well … until, abruptly, they didn’t. In 1718, two sloops under the command of a Royal Navy officer found Blackbeard at Ocracoke Inlet, off the Carolina coast, and put an end to his career in a hard-fought action. It ended with his severed head hung at the tip of his enemy’s bowsprit, giving rise to the local legend of Blackbeard’s ghost haunting Ocracoke Inlet, forever looking for his missing head.

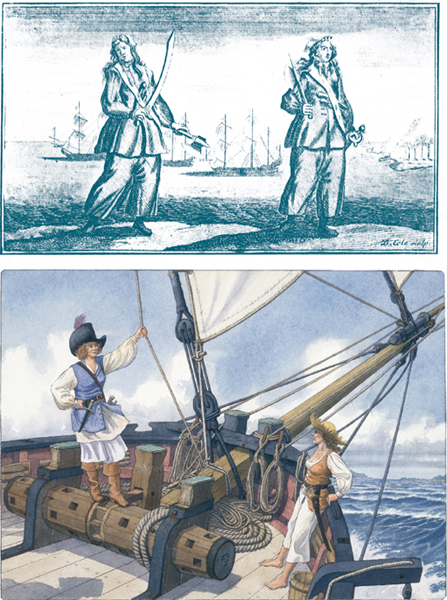

Meanwhile, other Nassau refugees carved their names in history just as notoriously as Blackbeard, notably the pirates Anne Bonny and Mary Read, two women in their twenties who both dressed and posed as men, when it suited their purpose, as it did when they coincidentally signed on as crew aboard Calico Jack Rackham’s sloop. There they met. Anne Bonny had abandoned a wastrel husband in order to sail away with Calico Jack. Mary Read, retired from a career in the British army, was now involved in an entirely different adventure. Both women would play the role of fierce young men when they wished, or become desirable females by changing clothes and attitudes. By all accounts, they could both be very seductive, but dangerous. When Mary Read set her eyes on a young lover, and that individual was challenged to a duel by another buccaneer, she would take on the challenger first, with pistols and cutlasses, and blow away that threat to her chosen mate.

In 1720, Rackham’s sloop was captured at Jamaica. Its whole company was put on trial, and most were given the death sentence, including Calico Jack and his two female crew. His women had been their sloop’s only real defense during the brief action, fighting on after Rackham and the men of his crew had fled below decks. There they had escaped the hail of fire from the pirate-hunting sloop that had overwhelmed them, but not their fate.

“If you had fought like a man, you wouldn’t have to be hanged like a dog,” Anne Bonny told Calico Jack when they were allowed to see one another before his hanging. Her own hanging was postponed because she was discovered to be pregnant at the time, which was Mary Read’s condition also. Mary died in prison with a fever. Anne’s fate is lost to history, except for the fact that she did not hang.

What did Anne Bonny and Mary Read actually look like? Many portraits were made of them after their popular stories were published, but their artists never saw their subjects, making for imaginative results. For instance, the 1724 engraving above shows a brutish pair with rhino-like bodies. Yet both young women were noted in contemporary accounts as very attractive when they wanted to be. A newer and opposite interpretation imagines them at ease and undisguised, having a chat on their sloop’s foredeck under a sunny Caribbean sky.