Learning to Be Soldiers

1775

The incursion into Canada, the patriots’ first major offensive expedition, would prove to be one of the most extraordinary efforts of the entire war. A critical role in the operation would fall to the itinerant teamster who had years ago followed Braddock into the Ohio Country and been flogged for his insolence.

In the summer of 1775, Daniel Morgan had volunteered to join the first troops specifically recruited for a national army. The hulking Virginian with the loud, twangy voice and the mad gleam in his eye took command of one of ten companies of “expert riflemen.” Congress had voted to raise these “continental” troops from the backwoods of Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania to reinforce the siege around Boston. These wild outlanders were experienced in frontier war, accustomed to hard living, and armed with an unusual firearm: the light, long-barreled, frighteningly accurate, uniquely American Pennsylvania rifle.

Now thirty-nine, Morgan was eager to support his “brethren in Boston.” Like many of the backwoodsmen, he knew the ways of Indians. His riflemen had a reputation for cunning and savagery that rivaled that of America’s natives. Congress viewed them as a secret weapon capable of delivering the British a lethal blow.

After the French war, Morgan had pursued his rowdy life, eager for fights, foot races, and bouts of drinking. He merrily joined in backwoods brawls described as “Biting, Butting, Tripping, Throtling, Gouging, Cursing,” and “kicking one another on the Cods.”1 The sport proved an excellent preparation for war.

During his late twenties, Morgan came under the influence of the teenage daughter of a local farmer. Contemporaries described Abigail Curry as “plain, sensible, and pious.” She passed on some of her education and her religious sensibility to the gruff backwoodsman. She bore him two daughters, Nancy and Betsy, during the 1760s, and they finally married in 1773. Daniel went no more a roving. He rented some land in the Shenandoah Valley to grow tobacco and hemp, and did well enough as a yeoman farmer to purchase a few slaves.

The news from Boston reawakened his taste for a fight. Like most participants, he expected the war to be exciting, successful, and short. Abandoning his family and farm for a few months seemed a small price to pay to take part in a drama that might endow its actors with immortality.

Enthusiasm for the cause made recruitment easy. Morgan preached glory and the rights of man in loud, rough terms that made sense to unschooled backwoodsmen. He took his pick of volunteers, selecting the biggest men, the best marksmen, and the hardiest fighters.

Congress had stipulated companies of sixty-eight men—Morgan signed up ninety-six in less than a week. The men possessed the instincts of hunters: deep patience, hair-trigger awareness of their surroundings, and the ability to withstand rain, cold, and hunger. Each was fitted out with a rifle and a tomahawk. Each carried a scalping knife, a nine-inch blade suitable for eating, whittling, or slicing human flesh. Instead of a uniform, the men wore their traditional dun-colored hunting shirts fashioned from heavy fringed linen, along with leather leggings and moccasins. This gear was practical and set them apart as the first of America’s special forces.

Morgan trained his men for three weeks in the rudiments of war as he understood it. On July 15, they marched toward Boston. Townspeople turned out to offer them bread, cider, and hearty cheers. Local militiamen marched alongside to show support. Virginia congressman Richard Henry Lee marveled at “their amazing hardihood, their method of living so long in the woods without carrying provisions with them.”

“They are the finest marksmen in the world,” John Hancock declared. “They do execution with their Rifle guns at an amazing distance.” Unlike a musket, a rifle, fully five feet long, had spiral grooves incised along the interior of its barrel. The ridges gave the ball a gyroscopic spin, causing it to fly far more accurately than one from a musket. To impress the locals, one man would confidently hold a five-inch target between his knees for his mates to fire at from forty yards. Then all would strip to the waist, paint themselves like Indians, and put on displays of ferocity.

These intrepid riflemen arrived in Cambridge on August 6, 1775, having tramped a total of nearly six hundred miles in three weeks, an astounding pace. They found themselves in a camp that was suddenly the third-largest city on the continent. Their arrival created a sensation. Their rough language mortified the local descendants of Puritans. They demonstrated the accuracy of their backwoods hunting implements for mystified New Englanders. John Adams thought a rifle “a peculiar kind of musket.”

As an elite force, the riflemen were given a separate bivouac and excused from routine camp duties. But a month of inaction wore on them. They drank rum, fought among themselves, and stole from surrounding farms. “They are such a boastful, bragging set of people,” an observer noted, “and think none are men or can fight but themselves.”2 When Washington asked for recruits to invade Canada, every one of them volunteered. Morgan’s Virginians and two Pennsylvania companies were chosen by lot.

* * *

Congress had initially assigned the attack on the fourteenth colony to General Philip Schuyler, commander of the Northern Department. The forty-two-year-old scion of a powerful Albany family, Schuyler supported the patriot cause but remained deeply suspicious of the rebels’ egalitarian notions. During the war with the French, he had served as a supply officer, a post suited to an experienced businessman.

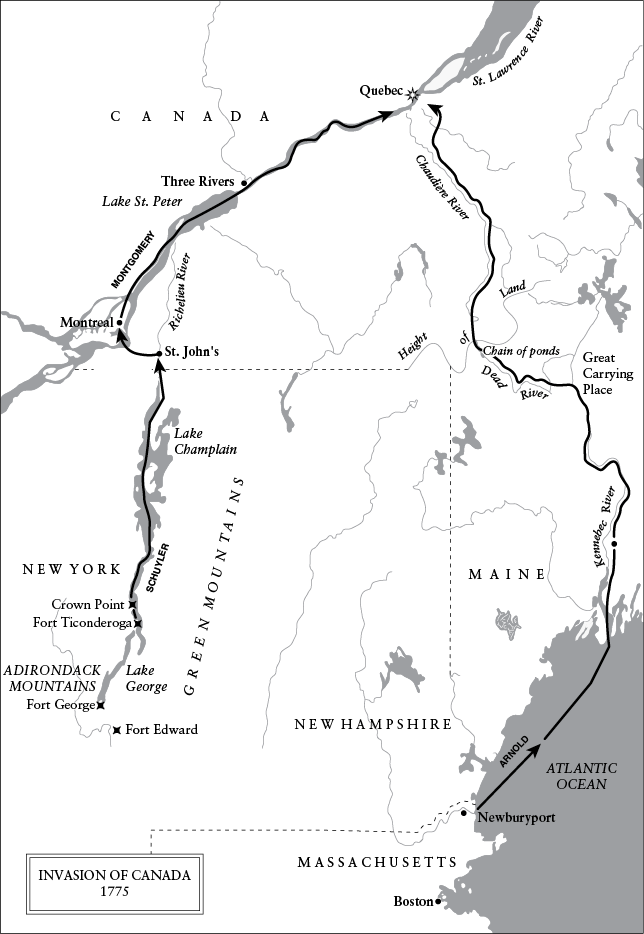

He agreed to the operation, then he delayed. In August, with the campaigning season slipping by, Washington turned the Canada invasion into a pincer maneuver. He would send another force north along a little-used route through Maine to threaten Quebec City while Schuyler’s men pushed toward Montreal. The British commander in Canada, Guy Carleton, would have to divide his meager force or relinquish territory to defend a single point.

Schuyler finally set out and besieged the British fort at St. John’s that Arnold had raided in the spring. While the operation was under way, the commander fell ill with “Barbarous Complications of Disorders.” He turned the mission over to his second in command, the former British officer Richard Montgomery. The veteran Montgomery questioned whether Schuyler had the “strong nerves” required for war.

* * *

While Montgomery’s traditional corps relied on artillery for its heavy hitting, the wing approaching through Maine would embody a new strategic idea. Relieved of the burden of heavy guns, the force would gain mobility. The lethal fire of the riflemen would, in lieu of cannon, give the force a long-range killing capability. The big backwoodsmen could also serve as shock troops for storming the walls of the city.

As the group was getting organized, Morgan sized up the officer chosen to lead this unique force: Benedict Arnold had returned to the cause. At thirty-four, Arnold was six years younger than Morgan. Both men were self-made, but in different ways. Morgan had spent months wandering through trackless forests with his rifle, sleeping under stars and rain. Arnold had negotiated with sharp-minded merchants and used his wits to turn a profit. In the course of the war, the two would emerge as the patriots’ most skilled natural fighters.

Washington told Arnold that “upon the success of this enterprise . . . the safety and welfare of the whole continent may depend.”3 In addition to the two hundred riflemen, Arnold picked eight hundred New England and New York militiamen, many of them veterans of Bunker Hill. In mid-September, the strike force, a total of 1,050 men, marched to coastal Newburyport, Massachusetts, where they would board on a flotilla of small ships for a dash up the coast. Before embarking, they staged a grand parade through town. Amid the cheers, the reality of the great task began to sink in. It dawned on one twenty-two-year-old volunteer that “many of us should never return to our parents and families.”4

Munching on the ginger that Arnold, the former apothecary, had thoughtfully provided, the men still succumbed to seasickness as they scudded 140 miles along the stormy coast. Yet in a few days they were gathering themselves at the mouth of the Kennebec River, preparing for a trek into the unknown.

The men loaded their supplies into two hundred boats that a local carpenter had slapped together, “very badly,” from green wood. Each twenty-foot-long vessel could hold up to a ton of supplies or six men. They carried forty-five days’ of food for the expected twenty-day trip—barrels of flour and of preserved beef and pork. Military supplies—powder and ammunition, as well as their own muskets and rifles—added to their load.

Like Arnold himself, most of the leaders were neophytes at war, guided as much by improvisation and guesswork as by experience. Lieutenant Colonel Christopher Greene, a cousin of Nathanael Greene, owned a Rhode Island mill. Major Return J. Meigs was a Connecticut merchant. Captain Henry Dearborn, a twenty-four-year-old New Hampshire physician, had marched his company toward Lexington the very day the news arrived, despite the fact that his wife had given birth that same morning. With John Stark, he had survived the worst of the Bunker Hill inferno. Heading off to Canada, Dearborn took along his black Newfoundland dog for companionship. The oldest and most experienced officer was forty-six-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Roger Enos. He had already been to Quebec with the British army in 1759. His men would haul the bulk of the expedition’s reserve supplies at the rear of the march.

At least two men took their wives. Joseph Grier’s spouse was a strapping six-footer. Jemima Warner went along because she was concerned about the health of her husband, James. Wives frequently accompanied husbands on military campaigns, but for women to sign on for such a perilous expedition was extraordinary. Another who made the trek was Aaron Burr, a zealous nineteen-year-old graduate of the College of New Jersey at Princeton, who served as a volunteer aide to Arnold.

The riflemen were the core of the force. Arnold put all three rifle companies under Captain Morgan. The experienced woodsmen would go first, blazing the trail for the others. Morgan was suited to commanding hard men. Later portraits show him with the angled nose and battered face of a seasoned pugilist. They downplay an ugly scar he carried on the side of his face. Serving with a ranger corps on the Virginia frontier after the Braddock debacle, he had ridden into an Indian ambush. A bullet had torn through his neck and cheek, knocking out his teeth. He had barely escaped with his life.

“His manners were of the severest cast,” one of his men wrote of Morgan, “but where he became attached, he was kind and truly affectionate.”5

* * *

Maine’s glacier-clawed landscape, with its three thousand ponds and lakes, offered a grim prospect for travelers. As the Kennebec River stepped toward the sea, it leaped over a series of rapids and waterfalls. At each, the men had to pole, paddle, and push the boats against the tumbling water. Or they had to unload the vessels, haul them out, carry them as far as the next manageable stretch, return for their equipment and supplies, carry that, reload the boats, and go on. Again and again they moved their sixty-five tons of supplies over these punishing portages. At one point, a soldier recorded, the river was “exceeding rapid and rocky for five miles, so that any man would think, at its first appearance, that it was impossible to get Boats up it.”

On October 10 they passed the last frontier settlement and plunged into “the greatest forest upon earth.” They would not encounter another human habitation for three hundred miles. They could see mountains “on each side of the river, high and snow on the tops.” In the brittle evening air, they heard the honking of great wedges of geese heading south. The weather turned severely cold, and they awoke each morning to find their clothes stiff with ice.

“Now,” wrote Private Caleb Haskell, “we are learning to be soldiers.”6

Morgan and his men forged a way over the Great Carrying Place, a series of portages between ponds, to the Dead River, so called because of its easy-flowing water. The crossing took five days. They hauled the boats and supplies through “Spruce Swamps Knee deep in mire.” Dysentery ravaged the ranks. Arnold ordered a log hospital thrown up. He was already down to 950 men and twenty-five days’ provisions.

On they moved into the “eternal night” of the wilderness. “A dreary aspect,” one man wrote, “a perpetual silence, an universal void, form the face of nature in this part of the world.”7 A prolonged, drenching rain caused the river to rise twelve feet and fill with debris. Rifleman George Morison wrote in his journal about “stumbling over fallen logs, one leg sinking deeper in the mire than the other. . . . Down goes a boat and the carriers with it. A hearty laugh prevails.”8

On October 23, as men tried to dry their sodden clothing around fires, Arnold noted that the increasingly intense cold would freeze the ground and make walking easier. Most of the troops shared their leader’s hopeful outlook. Fighting men had an advantage, wrote Private Morison: “Great as their sufferings often are, they are never doomed to endure the miseries of those terrible spectres, spleen and melancholy.”9

Then came the kicker. Enos and his officers, trailing behind the rest with the bulk of the provisions, decided to turn back. They took food, weapons, medical supplies, and a third of the army. Enos fully justified his decision to disobey orders and quit the apparently suicidal course that Arnold, Morgan, and the others had embraced. He had been defeated not by the enemy but by America’s vast terrain and the fear it engendered.

“In an absolute danger of starving,” the rest of the men stood one hundred miles from the settlements in Quebec, two hundred miles from those in Maine. “No one thought of returning,” a soldier recorded in his diary. “We found it best to endure it patiently.” Arnold went ahead in a canoe, promising to send supplies back as soon as he made contact with civilization over the mountains.

The men continued to ascend, now moving along a chain of ponds that were the source of the Dead River. They reached the divide that marked the border with Canada. They watched the mountains close in. “Every prospect of distress,” one man wrote, “now came thundering on.”

They had survived two weeks on half rations. By October 28, almost all food was exhausted. Each man was allotted a pint of flour and less than an ounce of salt pork per day. Many miles of hard marching lay ahead.

Passing onto the downhill phase of the journey did not make the going easier. Daniel Morgan quickly discovered why the river they needed to follow was named Chaudière, French for “cauldron” or “boiler.” Boarding his boat, he hurtled along in the white water until the rapids flipped the craft over. He lost not just food, personal possessions, and guns, but the first man of the expedition to drown.

Still, the unspoiled beauty of the scene moved some of the men. “This place was not a little delightsome,” noted Isaac Senter, the expedition’s surgeon, “considering its situation in the midst of an amazing wilderness.”10

They entered a morass of streams and marshes. “After walking a few hours in the swamp,” a participant reported, “we seemed to have lost all sense of feeling in our feet and ankles.” The men stepped along “in great fear of breaking our bones or dislocating our joints.”11 To be disabled was certain death. On October 30 they waded six miles through a swamp “which was pane glass thick frozen.” Mrs. Grier held her skirts above her waist, but none of the men “dared to intimate a disrespectful idea of her.”

Their provisions exhausted, they ate moss, candles, and lip salve. They ate “roots and bark off trees and broth from boiling shoes and cartridge boxes.” On the first day of November they killed two dogs, one of them Henry Dearborn’s Newfoundland, and ate them “with good appetite, even the feet and skins.”

As one group prepared to plunge through yet another morass, Jemima Warner noticed that her husband was missing. She went back “with tears of affection in her eyes” and found him lying exhausted along the trail. She sat with him for several days in the cold until he “fell victim to the King of Terrors.” She covered his body with leaves and later arrived in camp carrying his rifle and powder horn.

All of this they experienced in the unearthly mental state that accompanies extreme hunger and fatigue. Their minds became taut wires through which they could hear the hum of the stars. The mountains and clouds, trees and rocks, as light as their bodies, seemed to float dreamlike in the cold. The aroma of pine and moss became intense.

“We are so faint and weak, we can scarcely walk,” one man noted. Another said, “That sensation of the mind called ‘the horrors,’ seemed to prevail.”12

* * *

While Morgan and Arnold struggled through Maine, Richard Montgomery and the force marching along the western route to Canada had run into problems of their own. The five hundred British soldiers at St. John’s managed to hold off Montgomery’s two thousand inexperienced men for two miserable months.

War had seared Montgomery long before the Revolution commenced. The son of Anglo-Irish gentry, the young man had been raised to fight. During the Seven Years’ War he had helped the British take Fort Ticonderoga and Montreal. He had endured a full range of slaughter and misery while campaigning in America’s wilderness; he had fought through the hellish siege of Havana as the British grappled with Spanish forces. After returning to England, he languished. Europe was exhausted by war. Promotions dried up. His career stalled.

Montgomery himself was exhausted. He sold his commission, left the army and moved to America, seeking the life of a simple farmer. He renewed his connection with heiress Janet Livingston, whom he had met during his period of service. Their marriage in 1773 joined Montgomery to one of the most powerful families in America. The couple settled on a Hudson Valley farm. His wife wanted a child. He did not. Melancholy, the eighteenth-century term for depression, haunted him. “My happiness is not lasting,” he wrote. “It has no foundation.”

He signed on to defend his adopted country and was appointed brigadier general under Schuyler. He felt it a “hard fate to be obliged to oppose a power I had been ever taught to reverence.” Before he left to join his men and to fight against his former comrades, he said, “‘Tis a mad world, my masters, I once thought so, now I know it.”13

The New York soldiers who fought under him at St. John’s knew that in Montgomery they had a commander with strong nerves, one of the most competent and inspiring officers on the continent. When they finally overran the post, they also captured a good portion of all British regulars in Canada. Their victory delivered the enemy “a most fatal stab.” The men’s own nerves were growing accustomed to fire and death. They were sure they could take Quebec and perhaps end the war before winter.

But Montgomery saw that time was slipping dangerously past. The enlistment of a portion of his troops would run out at the end of November. Days were growing shorter. The cold, dirty weather was turning roads to muck.

The British governor of Canada, General Guy Carleton, with only 130 soldiers left to command, abandoned Montreal. He lacked faith in the French Canadians, who had, he thought, “imbibed too much of the American Spirit of Licentiousness and Independence.”14 He hurried back to Quebec, allowing the Americans to take Montreal without a shot.

Yet Montgomery’s foreboding continued. In his letters to Janet, he often included the phrase, “If I live . . .” He admonished her not to send him “whining letters” that “lower my spirits.”

* * *

On November 2, the supplies Arnold had promised began to reach his scattered and famished troops: two oxen, a cow, two sheep, and three bushels of potatoes. The cattle were butchered and eaten on the spot, the bloody hides fashioned into crude moccasins. Soon cornmeal, mutton, and tobacco arrived. It was “like a translation from death to life,” one man noted. “Echoes of gladness resounded from front to rear.”

The inhabitants around Quebec were astounded to see the bearded, emaciated troops emerge from the wilderness. Of the 1,050 men who started, 675 had completed the miraculous journey. If they had reached the city a few days earlier, Arnold and his men might have taken it. But they found that a corps of loyal Scots Canadians had just arrived to defend the walled city. Arnold chose to withdraw twenty miles and wait for Montgomery. He reported to Washington that his men were “almost naked and in want of every necessity.”

In early December, Montgomery arrived, leading only three hundred of his New York men. He had left some to secure Montreal. The rest had departed when their enlistments expired, or had fallen ill or deserted. Arnold’s men cheered the arrival of this diminished prong of the grand pincer. They cheered the food, supplies, and winter clothing that Montgomery brought with him. The addition of several hundred Canadian militiamen, who had chosen to join the cause of those they called Bostonois or “Congress Troops,” raised their numbers to more than thirteen hundred.

General Carleton organized his defenses, but remained pessimistic. “We have so many enemies within and foolish people, dupes to those traitors,” he wrote to London authorities, “that I think our fate extremely doubtful.”15

From outside the city walls, Montgomery sent Carleton word that he was having trouble restraining his hordes from “insulting your works” and taking “an ample and just retaliation.” The British commander, who had fought with Montgomery in the West Indies, sneered at the threat.

During the next few weeks, the two sides engaged in a desultory cannon duel. The Americans tried building fortifications of ice, which enemy guns quickly splintered. One cannonball demolished Montgomery’s carriage and killed his horses seconds after he stepped down, one of his several brushes with death. Another shot decapitated a woman drawing water from a stream. It was Jemima Warner, who had left her dead husband under leaves back in the mountains.

Morgan’s riflemen fired at long range toward any defender who appeared on the walls. After they shot a sentry through the head, a British captain complained about the “skulking riflemen . . . These fellows who call themselves soldiers . . . are worse than savages. They lie in wait to shoot a sentry! A deed worthy of Yankee men at war!”

The soldiers suffered from “lice Itch Jaundice Crabs Bedbugs and an unknown sight of Fleas.”16 Worse—smallpox soon began to prostrate one man after another.

General Montgomery mulled his options. Tall, slender, balding, with a handsome, slightly pockmarked face, he was beloved for “his manliness of soul, heroic bravery, and suavity of manners.” Staring at the wintery walls of Quebec, he knew that he must act. Most of the New England troops had enlisted only through December. No pleading could convince them to stay past their promised time. The only course left was to take Quebec by storm. With limited manpower, the key to entering the city was to concentrate on one point. But where?

Montgomery chose the Lower Town, the sprawling waterfront commercial district at the foot of the cliffs on which Quebec stood. “I propose amusing Mr. Carleton with a formal attack, erecting batteries, etc.,” Montgomery wrote to Schuyler in the sardonic tone of the day, “but mean to assault the works, I believe towards the lower town, which is the weakest point.” Taking the Lower Town would cut off the garrison from the water. A threat to burn the warehouses and places of business might induce the inhabitants to surrender.

On December 16, Montgomery put the question to his officers. They debated the matter: a few staunchly opposed the foolhardy attempt, the majority voted to lead their men against the city’s walls. They agreed that the faint of heart could bow out, only volunteers would be included.

“Fortune favors the brave,” Montgomery stated. On the evening of Christmas Day, the general gave a rousing address to the troops. “General Montgomery was born to command,” one man wrote. He sweetened the prospect of attack, proclaiming that “all who get safe into the city will live well,” plundering as they pleased. They would attack using the “first strong north-wester” for cover.

Although Montgomery kept up a brave front for his men, he was feeling the strain. “I must go home,” he had written to Schuyler. “I am weary of power and totally want that patience and temper so requisite for such a command.”17

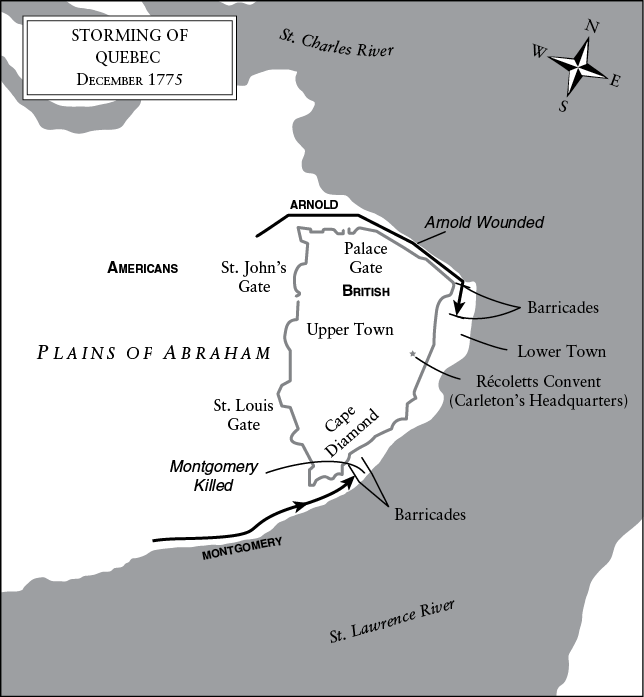

Quebec sat on a rocky bluff at the end of a peninsula between two rivers: the Charles on the northwest side, the tidal St. Lawrence on the southeast. Montgomery’s plan was to set fires at the western gates as a diversion and attack the Lower Town from two directions. He would personally lead an advance party along the path between the bottom of the bluff and the St. Lawrence. Arnold would advance on the Charles side with the main force.

By December 29, it seemed likely the clock would run out before the men could act on the plan. Many of the soldiers were already packing, settling debts, and preparing to return home on January 1. The weather, which had tormented them during the march, now remained frustratingly clear. If they attacked without the cover of a storm, the defenders inside the walls could anticipate and counter every move.

The next evening it began to snow. A screeching gale swept in from the northeast. Word went out for the men to be ready at midnight. They would attack on the last day of 1775.

Doctor Isaac Senter, the battalion physician, remembered that General Montgomery was “extremely anxious” during the preparations. Fortune, Montgomery had written, although it might favor the brave, “often baffles the sanguine expectations of poor mortals.”

Waiting in darkness, the troops hunched against the fanged blizzard. At four in the morning, rockets fired to coordinate the separate attacks. Artillerymen working mortars began to lob bombs into the city. The time for action had come.

Montgomery led his three hundred New York musketmen on a mission known as a “forlorn hope.” Derived from a Dutch military term verloren hoop, “detached troop,” it had nothing to do with hope but simply meant an advance assault force. Yet the English words carried their own connotation and fit the tenor of Montgomery’s mind.

His contingent descended the steep path to the river. Accompanied by his officers and by workmen equipped with axes and saws, he took the lead. The soldiers strung out behind him. They crept along the narrow ledge between the river and the steep rock cliff on their left. The bitter wind took their breath away.

The river had thrown large blocks of ice onto the path. It took them an hour to scramble two miles. They reached a barricade that Carleton had ordered built to protect the Lower Town. The palisade of stakes was undefended. Carpenters hacked an opening. Beyond, officers made out a two-story blockhouse, its black gun portals staring blankly. Nothing moved.

Every second was precious now. Rather than wait for his straggling men to come up, Montgomery chose to advance with fifteen officers. He drew his short sword with its silver dog’s head pommel. He motioned his men forward into the snowy darkness.

* * *

On the opposite side of the peninsula, Daniel Morgan and his riflemen were marching into Lower Town at the head of the main body of six hundred soldiers that Colonel Arnold commanded.

“Covering the locks of our guns with the lappets of our coats,” Private John Joseph Henry recorded, “holding down our heads (for it was impossible to bear up our faces against the imperious storm of snow and wind), we ran along the foot of the hill in single file.”18 Unseen defenders fired down on them from the walls, which loomed on the rocky promontory to the men’s right.

When they reached one of the barricades blocking the road, Arnold ordered Morgan and his riflemen to assault the obstacle. The riflemen surged forward. They ran to the log wall and fired point blank through the loopholes. The shots echoed, the flashes lit the swirling snow. A fragment of a ricocheting ball tore through Arnold’s left calf. Unable to stand, his boot overflowing with blood, he allowed himself to be helped to the rear.

Morgan ordered a scaling ladder placed against the barrier and, he later reported, “for fear the business might not be executed with spirit, I mounted myself.” A musket blast scorched his face. He fell back. Enraged, he rose and scrambled up again. His momentum carried him over the parapet. He landed on a cannon, “which hurt me exceedingly.” As the riflemen swarmed over the top behind him, fifty enemy soldiers fled in panic. Dozens surrendered as the Americans rushed into buildings beyond.19

A number of the officers present outranked Captain Morgan, but in the crisis, the younger men deferred to his age, size, and air of cold command. The Virginia rifleman took charge. The moment was ripe. Enemy soldiers, especially the French-Canadian militiamen, were surrendering. Panic was gripping the populace. Some townspeople were welcoming the invaders with shouts of Vive la liberté! The tide seemed to have turned. The arrival of Montgomery’s contingent from the opposite direction would hammer home the victory.

General Carleton did not panic. He sent his limited force of defenders to the northern walls to fire down on Arnold’s men as they streamed into the Lower Town. Amid the chaos, Carleton made two critical decisions. First, he marshaled defenders to rush out and take a stand against the Americans at a second barricade closer to the city walls. Then he sent sixty of his scant remaining men through the Palace Gate on the northwest side of the fortified city. They would tread in the footsteps of Arnold’s men to attack them from behind.

General Montgomery had still not arrived. Morgan urged that they should rush ahead and assault the town as planned. But now the others asserted their rank. Leaving a mass of prisoners lightly guarded in their rear would be a mistake. It made more sense to solidify their gains and wait for Montgomery. A frustrated Morgan argued to no avail.

Time ticked away. An impatient Morgan went to look for troops who had gotten lost near the docks. A tepid light was staining the eastern sky. When enemy troops began to congregate at the second barrier, the American officers finally allowed Morgan to attack. Running ahead with his riflemen, he collided with British regulars. A lieutenant demanded his surrender. Morgan’s answer was to shoot him in the head. But enemy fire now forced the Americans to take cover in doorways. They tried to pick off the soldiers firing from the second barricade. Morgan moved among them, encouraging and rallying. From the center of the street, he directed their fire. “Betwixt every peal the awful voice of Morgan is heard,” one of the riflemen remembered, “whose gigantic stature and terrible appearance carries dismay among the foe wherever he comes.”

The gray light of a snowy day revealed the dire situation: facing defenders far more familiar with the lay of the land, the Americans found the momentum of the battle going against them, and still no sign of General Montgomery. Morgan continued to urge on his troops. “He seems to be all soul,” the account continued, “and moves as if he did not touch the earth.”20

But the attackers’ situation continued to erode. The British regulars advancing from behind captured some Americans who had gotten lost in the urban maze. The British took up a defensive position at the first barricade, hemming in the Americans between the two walls. The prospect of victory dissolved as groups of disorganized patriot soldiers began to surrender rather than be killed. Morgan pushed for an immediate escape attempt. The other officers overruled him.

As he saw men throwing down their weapons around him, Morgan “stormed and raged.” He broke into tears of angry frustration. He would not give up. He would not concede that the awful ordeal had been for nothing. But surrounded, backed against a wall, he finally had to relinquish his sword.

The attack was over. In three and a half hours, 60 Americans had been killed or wounded, 426 captured. More than a third of the army in Canada had been wiped away. For all they knew, the American cause may have gone down to defeat with them.

Morgan and the others were taken to an improvised prison. A British officer wrote home, “You can have no conception of the Kind of men composed their officers. Of those we took, one major was a blacksmith, another a hatter. Of their captains there was a butcher . . . a tanner, a shoemaker, a tavern keeper, etc. Yet they all pretended to be gentlemen.”21

The Americans soon learned why General Montgomery had never arrived on the scene that snowy night. As he had rushed through the barricade with the lead unit of his forlorn hope, defenders in the blockhouse had greeted them with the roar of a cannon. The charge of grapeshot, a mass of lead balls that turned the piece into a giant shotgun, “mowed them down like grain,” one of the defenders observed. Montgomery and six of his officers were torn apart. The shock induced the others to turn back. Fortune had indeed baffled the expectations of poor mortals.

* * *

Montgomery instantly became a symbol of the sacrifice that was required to win Liberty. The fall of a great man testified to the seriousness of the cause. “Weep, America,” an officer wrote to Montgomery’s brother-in-law, “for thou hast lost one of thy most virtuous and bravest sons!”

America wept. Congress voted to erect a monument in Montgomery’s honor. “In the Death of this gentleman,” Washington wrote, “America has sustained a heavy Loss.”22

Janet Montgomery never remarried. She lived for half a century, treasuring the memory of the man she called “an angel sent to us for a moment.” Childless, she corresponded with some of the many children named for her late husband, encouraging them to live up to his virtues.

Americans had entered the conflict convinced that free warriors fighting for liberty could vanquish professional soldiers. The notion held both truth and falsehood. At Concord, at Bunker Hill, and in the phenomenal feat of arms that was the invasion of Canada, spirit and patriotism had made up, in part, for discipline and experience. Amateur soldiers and neophyte officers had come close to snuffing out British sovereignty in North America. The men who attacked Quebec had marched with hopeful hearts. They had learned the lessons that Montgomery had understood before they started: that war is cruel, fortune fickle, liberty costly.

Washington sat frustrated before Boston, his army evaporating, recruitment slow, supplies lacking, the first heat of enthusiasm for the cause gone. In the spring, British reinforcements would arrive in numbers. He needed a victory.