Sudden and Violent

1776

“Whoever commands the Sea must command the town,” Major General Charles Lee wrote Washington from New York.1 The British commanded the sea—the guns of the warship Asia already glowered at the city from the harbor. With more ships, the enemy could pulverize defenses and land troops at will. “Should they get that town and Command of the North River,” Washington worried, “they can Stop the intercourse between the Northern & Southern Colonies upon which depends the Safety of America.”2

Last autumn’s Canada expedition had aimed to secure the northern end of the critical Hudson-Champlain corridor. The prospects of victory there were now dashed. New York City, Washington declared, was “the place that we must use every endeavor to keep from them.” To assess the situation, he sent Lee, whom he valued as “the first officer in Military knowledge and experience we have in the whole army.”3

A commercial hub ever since the Dutch merchant Peter Minuit established a trading post there for the West India Company in 1626, New York City occupied a cramped square mile at the southern tip of Manhattan Island. The spindle-shanked General Lee recognized the dilemma: New York must be held; New York could not be held. The loss of the colonies’ second largest city and major commercial port would strike the rebellion a critical blow; defending an island without naval superiority was futile. The best he could advise was to erect fortifications that would make it “expensive” for the British to prevail. He quickly laid out plans for gun batteries on the East River and the Hudson, also known as the North River. Barricades would block the ends of the streets and forts would guard key locations around Manhattan and adjacent Long Island.

The work had to be done quickly. Spring was coming and British regulars were certainly on the way from England. They would be accompanied, rumor had it, by legions of professional soldiers hired from the principalities of King George’s relatives in Germany.

Just as Lee began to organize work parties, he discovered that General Henry Clinton had left Boston and was headed toward the southern colonies, intent on establishing a base of operations in Virginia or the Carolinas. Three thousand additional troops from Ireland commanded by Lord Cornwallis would join him. Together, they would open a new front in a poorly defended territory that was rife with loyalists.

Congress turned frantically to General Lee. “We want you at N. York—We want you at Cambridge—We want you in Virginia,” John Adams wrote.4 With work under way in New York, the South took precedence. Lee rode off to shore up the defenses of cities there. He handed over command to an inexperienced local officer who was almost as eccentric as Lee himself.

* * *

William Alexander had grown up in New York. His father, a Scottish immigrant, had prospered as a lawyer and investor. His Dutch mother, an astute businesswoman, had amassed her own fortune. The doting parents had given young Billie a first-rate education. His aptitude for science impressed his teachers. His marriage to Sarah Livingston cemented his connection to one of New York’s most influential clans—Sarah’s cousin Janet was the widow of the martyred Richard Montgomery.

The French and Indian War broke out when Alexander was in his late twenties. He served briefly as secretary to a family friend, William Shirley, the provincial commander who replaced General Braddock. Having botched the early phase of the war, Shirley was called to London to explain himself. Alexander decided to go along in order to defend his mentor and to garner payment for some of his own cash outlays.

He had planned to visit England for a few months. His stay stretched to five years. The reason: William Alexander had fallen in love with British aristocracy. He could not get enough of lords and ladies, of elegant conversation, country estates, and riding after hares and hounds. He lived on fatted geese and fortified wine. He came to know bluebloods like Lord Shelburne, the Duke of Argyle, and Lord Bute, who would become prime minister under George III. Styling himself an expert in colonial affairs, he murmured advice into the ears of the ruling class.

Then one day it dawned on him that he was just as worthy as the worthies. A bit of digging in the archives would surely prove his connection to that distant Alexander whom King James I had dubbed the Earl of Stirling in Shakespeare’s day. The title would give him a claim on the American lands the king had promised to the bygone earl: ten million acres across Canada, Maine, and Long Island, enough to support a lavish life. One of his friends laughed when Alexander revealed his plan, thinking it a joke.

It was no joke. In Edinburgh, Alexander and a team of solicitors strained their eyes over ancient documents. Soon they compiled a tangled family tree that, yes, did seem to indicate that the young American was in line for the title. The Scottish Lords approved, but British peers, whose nod was needed to pursue the land claim, scoffed.

No matter. Homesick at last, Alexander returned to America, where he would ever after remain Lord Stirling. His wife was Lady Sarah, his daughters Lady Mary and Lady Kitty. They rode around in the most sumptuous, the most vulgar coach on the continent. In Basking Ridge, New Jersey, thirty-five miles west of New York, the new lord built himself an opulent country home. Famous for his hospitality, Lord Stirling tippled and dined as became a lord. He pursued his interest in science, publishing a paper on his observation of a transit of Venus across the sun. His spending so far outpaced his income that his lordship soon found himself bankrupt. He sponsored a lottery to raise money. It failed. Sheriffs began to sell his household possessions at auction. Then came the Revolution.

A debauched, forty-nine-year-old patrician born to privilege, a self-styled nobleman, Lord Stirling would seem to be the archetype of the American Tory, steadfast in his loyalty to the Crown. Instead, he wholeheartedly embraced the cause of the rebels. Some accused him of using the rebellion to slip out from under his debts, but any such relief could hardly be worth the enormous risk he ran in siding with treason. His motives were sincere—Lord Stirling, in spite of his fascination with aristocracy, was a child of the Enlightenment.

He energetically recruited New Jersey militiamen, boosting the cause in that wavering colony. In spite of his scanty military experience, he soon found himself in command of the entire body of troops raised there. Congress commended his “alertness, activity, and good conduct” after he led a raid on a British cargo ship in the harbor. The representatives made him a brigadier general in the Continental Army.

Stirling certainly looked the part. Red-faced and bald, he was “a man of noble presence,” who presented “the most martial Appearance of any general in the service.”5 General Lee summoned Stirling and his regiments to New York to help prepare the city’s defenses. Lee considered him “a great acquisition” and on departing gave him command of the single most critical location in America.

Lord Stirling followed General Lee’s defensive plan to the letter. He enlisted a thousand citizens to help, including members of the patriotic gentry, who toiled so hard with their delicate hands that “the blood rushed out of their fingers.”6 By March 20, Stirling, who had described himself as a “young beginner” when he was appointed, could report that the effort was hurtling ahead. Ever optimistic, he thought it would be an “easy summer’s work” to secure the whole continent. He did not yet know that General Howe, now in the process of abandoning Boston, was determined to take New York.

* * *

George Washington arrived in the city in late April 1776. Looking over the situation, he wrote, “The plan of defence formed by General Lee is, from what little I know of the place, a very judicious one.”7

Command at New York had passed from Lord Stirling to Israel Putnam, one of the original major generals in the Continental Army. Putnam, whom a historian described as looking like a “cherubic bulldog,” wore the aura of a folk hero.8 As a young man, he had crawled into a cave to kill a dangerous wolf. He had fallen prisoner to Indians who nearly roasted him alive. During the French war, Putnam had held General Howe’s dying older brother George in his arms after the fighting near Fort Ticonderoga. Later, Putnam had survived a hurricane and a shipwreck in Havana.

The fifty-eight-year-old was still game. He declared martial law in New York and imposed a curfew. On his own initiative, he led a thousand militiamen to occupy Governor’s Island, at the mouth of the East River, a thrilling reprise of his seizure of Bunker Hill. When Washington arrived, Putnam became his second in command. The experienced Horatio Gates, another former British officer who had enlisted in the patriot cause, served as adjutant general, the army’s chief administrative officer.

Washington commanded nearly ten thousand men. To New Yorkers, the soldiers were rustics. “They have all the simplicity of ploughmen,” an urbanite observed. For their part, the New England militiamen were awestruck: “This city York exceeds all places that ever I saw,” one said.9

Across the East River, the western end of Long Island rose to form the modest highlands now known as Brooklyn Heights. Lee had seen the necessity of holding this ground and Lord Stirling had started building a four-sided citadel there. The cannon of Fort Stirling would threaten British ships in the river and protect the city from the east.

To lead the forces defending Long Island, Washington turned to another inexperienced officer. He saw something of himself in the young Nathanael Greene: a certain solidity, an attention to detail, a modest equanimity. Like Washington, Greene had missed the chance for a formal education, but also like Washington, he was a learner with a mind grounded in practicality.

On Long Island, Greene set his troops working to finish Lee’s defensive plan. In addition to Stirling’s citadel, he constructed a string of forts meant to seal off the area facing New York. Ditches and ramparts would join the strong points across the thick peninsula. The men erected a tangle of sharpened tree branches, a structure known as an abatis, the eighteenth-century equivalent of barbed wire. These veterans of the spade transformed Greene’s book knowledge into formidable defensive works.

Greene issued strict orders for the men to perform guard duty according to the book and to avoid wounding “the Modesty of female decency” when bathing nude in local ponds. Even coarse language he deemed “unmanly and unsoldier like.”10

Brooklyn was then a small hamlet in the agricultural expanse of Kings County. The word derived from breuckelen, Dutch for “broken land” or “marsh.” Large areas were drowned with salt water at high tide. Living in close quarters near swamps, surrounded by flies and mosquitos, the men soon began to fall to typhoid and typhus, known collectively as “putrid fever.”

“The air of the whole city seems infected,” wrote an American doctor. Many complained of “the stench that rose from the American camps.” Illness spread, killing some and leaving many groaning in barns and sheds. By July, every third man was laid low.

* * *

Washington’s senior officers, exercising the privileges of rank, tried to maintain a semblance of civilized life. They occupied the mansions of the city’s departed loyalists and visited each other’s headquarters for dinner. Washington had brought Martha to New York; Knox and Greene invited their wives, as well. The pretty, vivacious Caty Greene’s sharp wit and flirtatious nature at times unsettled her insecure husband. Caty enjoyed the excitement and formed a close relationship with the motherly Martha Washington, who had turned forty-five in June. Knox’s daughter, named Lucy after her mother, had been born during his wife’s trip from Boston in April. Henry doted on her, but he also fretted about the presence of the pink infant in an armed camp.

Knox had established his headquarters in a luxurious house abandoned by a loyalist at the southern tip of the city. He and Lucy liked to breakfast in the second-floor room where arched windows offered a panoramic view of the harbor. On Saturday, June 29, they caught sight of ships sailing into the lower bay. Ships and more ships. And still more. The white sails of forty-five warships and transports soon fluttered above the water.

The arrival of the British fleet sparked an uproar. American guns boomed warnings. Troops sprinted to their posts. Imagining Lucy and their baby in the line of fire, Knox nearly panicked. “My God, may I never experience the like feelings again!” he later wrote.11 To disguise his fear, he scolded Lucy “like a fury” for having stayed against his advice. Now she had to go, as did most of the remaining women and children in the city.

Knox hurried to make sure his guns were ready. He thought his large cannon would intimidate any invader, but he had not imagined a force like this one. Just five ships of the line, the massive battleships of the day, wielded more guns than Knox could muster to defend the entire city. The naval guns would be handled by experts; Knox had to entrust his pieces to inexperienced infantrymen drafted from the ranks. One neophyte subordinate was a twenty-one-year-old Kings College student named Alexander Hamilton, whom Knox assigned to the Battery at the south end of the island.

Within four days, 130 ships had anchored in the outer harbor, many of them troop transports. The redcoats of General Howe’s army were disembarking on Staten Island without opposition—the island’s militia had collectively gone over to the enemy. The British set up camp and waited for yet more troops. Rather than let the American rebellion smolder, King George’s ministers had decided to extinguish it with unanswerable power.

Washington, with Lee’s warning about command of the sea echoing in his mind, was dramatic in summing up what was at stake. “The fate of unborn millions,” he wrote, “will now depend, under God, on the courage and conduct of this army.”

Then urgent news arrived at New York from Philadelphia. In a letter, John Hancock, the president of Congress, was understated: “That our affairs may take a more favorable turn, the Congress have judged it necessary to dissolve the connection between Great Britain and the American colonies.”12 It was the monumental step that Washington, Knox, and other military men had been urging for months. On July 9, Washington had the Declaration of Independence read to all his men.

An excited John Adams declared, “We are in the very midst of a revolution, the most complete, unexpected and remarkable of any in the history of nations.”13 In New York City, jubilant rebels pulled down the 4,000-pound gilded lead statue of the king, hacked off his majesty’s head, and hauled away the metal to make musket balls.

A few days later, Knox wrote to Lucy, who was living in yet another temporary home in Connecticut, “I thank Heaven you were not here yesterday.” On a lovely summer afternoon, two British warships, the Rose and the Phoenix, accompanied by a schooner and two tenders, broke away from the fleet and headed north. They entered the Hudson River, firing at American defenses as they went. They even unloosed a broadside into the city itself, sending civilians screaming in terror.

Knox’s artillery corps fired two hundred cannon rounds without seriously damaging the vessels. The captain of the Rose and his officers sipped claret on the quarterdeck as the ships skimmed unscathed past the guns of Fort Washington, the Americans’ last line of defense at the north end of Manhattan. By the end of the day, the British ships were anchored thirty miles above the city, ready to cut waterborne supplies and to incite local Tories.

The foray dismayed and embarrassed Henry Knox. Some of his men had been drunk, more were incompetent. They were too “impetuous” around the guns, Knox observed. Their carelessness had caused several cannon, including two of Alexander Hamilton’s, to explode, killing six men.

If two ships could skim past the American gauntlet, so could the entire fleet. The British demonstration had suddenly drained New York City of its military value. The city had become a trap. If the British army were to secure a beachhead to the north, Washington’s own force, arrayed on two islands, would be cut off. His tentative optimism evaporated. Militarily, the best bet was to abandon the city, but Congress would not allow him to cede it without a fight.

Another group of warships now dropped anchor in the lower bay. They included the Eagle, the sixty-four-gun flagship of Admiral Richard Howe. Known as “Black Dick” because of his swarthy complexion, he was the dour older brother of General William Howe. He had come to America not only as naval commander but also as peace commissioner. The British ministers, blanching at the potential cost of another prolonged war, were willing to make concessions. A negotiated settlement would be a feather in the caps of the Howe brothers. Such a course seemed eminently practical even after Howe heard about the Declaration of Independence. That measure, said one of his aides, simply pointed up “the villainy and the madness of these deluded people.”14

Black Dick, fifty years old and a veteran of two wars, sent over his adjutant with a letter addressed to “Mr. Washington, Esq., etc. etc., etc.” Washington, whom John Adams would call one of the great actors of the age, was in his element. His bearing and gravity could not fail to impress. The general insisted on being referred to by his appropriate title. The et ceteras, the adjutant declared, implied everything. “Or anything,” Washington rejoined, “or nothing.”

Howe was authorized to pardon the rebels’ treason. Washington pointed out that “those who have committed no fault want no pardon.” If the admiral wanted to negotiate, he should apply to Congress, which spoke for the new nation. Knox attended the meeting and wrote that he “lamented exceedingly the absence of my Lucy” to enjoy this historic repartee. The British officer “appeared awe-struck, as if he was before something supernatural. Indeed, I don’t wonder at it. He was before a very great man.”15

The British military build-up around New York continued. Arriving troops moved into well-ordered camps on Staten Island and enjoyed the ripening melons and peaches. They raped local women—a young officer named Lord Rawdon complained that the wenches didn’t tolerate the assaults “with the proper resignation,” resulting in “most entertaining courts-martial.”16

On August 1, General Henry Clinton arrived with nine more warships, thirty-five transports, and three thousand veteran troops. He and Lord Cornwallis had attempted to capture the important southern port at Charleston. American general Charles Lee had arrived just before the British attack to help the citizens of Charleston prepare their defenses. Patriot guns had prevented the enemy from gaining the harbor. Unsuccessful in their southern adventure, a chastened Clinton and Cornwallis joined the main British army for the attempt against a much more important prize.

They were followed by yet another fleet of ships carrying Hessian soldiers. The Germans had been thirteen weeks at sea and were glad to step onto dry land. Now General Howe had assembled his army: thirty-two thousand trained and disciplined soldiers, along with four hundred warships and transports to move them at will. “A Force so formidable would make the first Power in Europe tremble,” was how the commander of a British escort frigate described it.17

To counter this host, Washington commanded twenty-eight thousand men in New York, only twenty thousand of them fit for duty. Many of the reinforcements who had streamed in during the summer were militiamen, eager but inexperienced. “Let their Force be what it will,” General Howe declared, “it can never stand against the veteran Troops commanded by the best Officers in Europe.”18

Washington struggled to guess Howe’s intentions. Why the maddening delay? Why did he not attack? There was, he wrote, “something exceedingly mysterious in the conduct of the enemy.” Tedious guard duty and continual false alarms abraded the nerves of Washington’s men and officers.

Then a grievous misfortune. The disease that had depleted Washington’s force struck Nathanael Greene, who had spent the summer preparing the fortifications on Long Island. On August 15, he reported being “confined to my Bed with a raging fever.” Five days later he was “sick nearly to death.”

A reluctant Washington replaced Greene with General John Sullivan. The former New Hampshire lawyer had been one of the first to respond to the crisis at Boston. Enthusiasm and political connections had won him high rank in the army. Earlier in the summer, the intense, dark-haired Irishman had led troops north to reinforce the crumbling American army in Canada, the remnants of the invasion led by Richard Montgomery and Benedict Arnold. Sullivan had blindly sent his men against a superior British force, then managed a chaotic retreat. Replaced by Horatio Gates, he had rushed to Philadelphia in a fit of anger to resign his commission. His friends convinced him to stay in the service.

Asked his opinion, Washington described Sullivan as “active, spirited, and Zealously attach’d to the Cause.” But, he said, Sullivan “has his wants, and he has his foibles. The latter are manifested in a little tincture of vanity, and in an over-desire of being popular.”19 Nevertheless, Sullivan’s political allies in Congress had promoted the ambitious soldier to major general. He lacked Greene’s innate judgment, as well as his familiarity with the geography of Long Island.

Two days later, on August 22, drums in the American camp beat “to arms.” The sound, after four months of waiting, sent an electric charge through the men. British transports were sailing across the placid waters of the bay to deposit eight thousand troops on the shore of Long Island. The redcoats quickly shoved back the rebel riflemen screening the shore. Now hidden from American eyes, boatmen ferried another fifteen thousand troops, the bulk of Howe’s army, across the bay. The British lined up in an eight-mile arc along the plains of southern Kings County.

Washington, still in New York, was told about the landing of the advanced guard. He decided it was a trick. Howe was trying to get him to commit his forces to Long Island before striking the main blow elsewhere, probably at Manhattan. The cautious Washington sent four more regiments across, but held his best troops in New York.

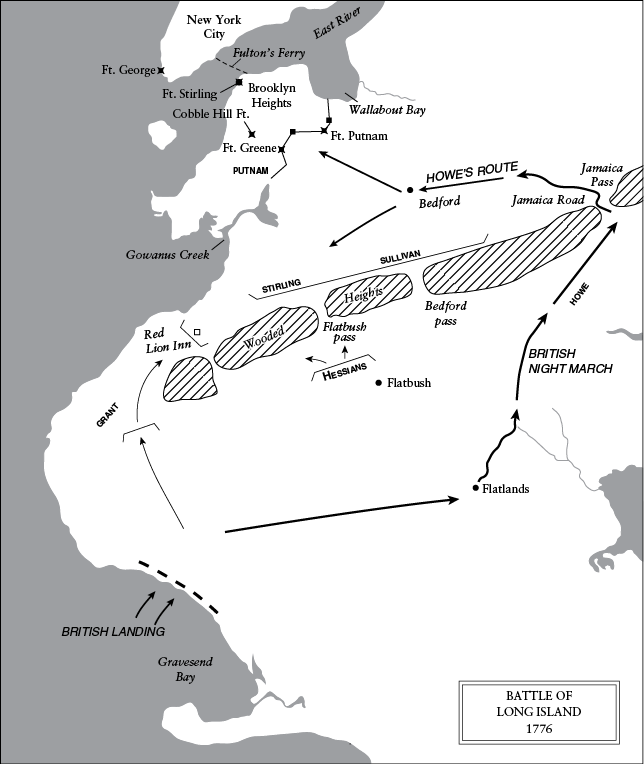

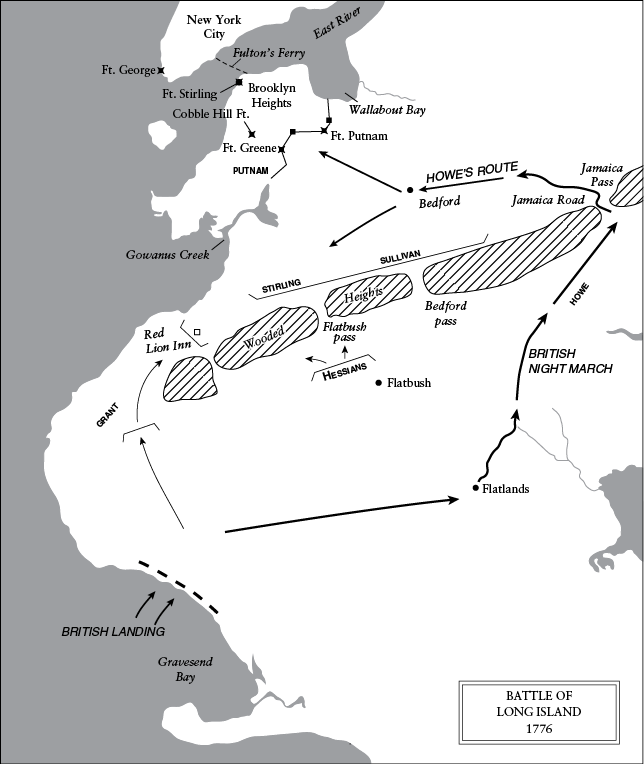

The next day, he went over himself to ride the ground with Sullivan. He concurred with a significant alteration that Sullivan had made in the plan laid down by Lee and implemented by Stirling and Greene. He would align three thousand men along a rocky, wooded ridge that ran ten miles obliquely in front of the fortified line. The steep, densely wooded, sixty-foot-high obstacle would serve as its own defense, preventing the passage of artillery or massed troops. Sullivan would station most of his own men at the three roads that cut through the ridge, one by the Gowanus marshes in the west and two more near the villages of Bedford and Flatbush in the center.

“The hour is fast approaching,” Washington wrote that day, “on which the honor and success of this army, and the safety of our bleeding country depend.”20 Trepidation suddenly swarmed Washington’s mind. Doubting the judgment of the vain and callow Sullivan, he abruptly named Israel Putnam overall commander on Long Island. Sullivan would assume responsibility only for the soldiers on the ridge; Putnam would direct the defense from inside the Americans’ fortifications.

For the second time that summer, the prickly John Sullivan saw himself superseded. For the second time that week, the defenders of Long Island came under a new commander. Yet Sullivan’s inexperience was a trait shared by all officers, including Washington. Directing a skirmish was one thing. Moving masses of troops over a wide area was a far more intricate matter. “The limited and contracted knowledge which any of us have in Military Matters,” Washington admitted, “stands in very little Stead.” They were, in fact, amateurs at war. Their resources were “some knowledge of Men and Books” and an elusive quality that Washington called “enterprizing genius.”21

That same day, 4,300 Hessians marched off transports to take up positions on Long Island opposite the center of the American line. Howe’s total force on the island had reached twenty thousand men.

On Sunday, August 25, Washington sent six more regiments to Long Island. He had divided his force almost in half in the face of a superior enemy, something all military textbooks condemned. Convinced the enemy was on “the point of striking the long expected blow,” he crossed to Long Island once again to survey the American position. With Putnam and Sullivan, he rode along the ridge that now formed the first line of defense. “At all hazards prevent the Enemy’s passing the Wood and approaching your Works,” he told Putnam.22 He warned that when the attack came, it was likely to be “sudden and violent.”

* * *

Sullivan commanded the center of the ridge in person. He stationed a force of riflemen to his left and assigned Lord Stirling to guard his right. On the night of August 26, Stirling was sleeping in his camp behind the line. His troops were arrayed across the Gowanus Road at the western end of the American front. Two of the best units in the Continental Army manned this important position. The First Delaware Regiment, under Colonel John Haslet, was the largest battalion in the army, eight hundred men outfitted in identical blue coats with white waistcoats. Colonel William Smallwood had recruited his First Maryland soldiers from some of the best families in Baltimore. The men of both units carried good English muskets fitted with bayonets. Unfortunately, the two colonels had been detained in the city that night to serve on a court-martial.

At midnight, a smattering of musket fire broke out—some British scouts had raided a watermelon patch near the Red Lion Inn just beyond the pass. Then the night settled into deep quiet. A couple of hours later, sentries on the Gowanus Road, their eyes tired from staring into darkness, spotted three hundred British regulars marching toward them like a bad dream. The guards ran for it. Awakened inside the fortifications, Putnam rode out to Lord Stirling’s camp and ordered him to meet whatever enemy force was advancing toward his position and to “repulse them.”

Stirling roused his young men at three in the morning, the hour of nightmare. Through keen blackness, with no experience of combat, they marched to meet the enemy. If this was to be the “grand Push,” it would be their first battle, the first battle fought by soldiers of the newly independent United States, and the first time that Americans faced the enemy without stone walls or breastworks for protection.

Stirling met Colonel Samuel Atlee and his Pennsylvania musket regiment retreating along the Gowanus Road. It was more than a skirmish, Atlee told him. They faced a large body of troops commanded by General James Grant, a fat Scotsman who had earlier bragged about the ease with which he would whip the Americans. His men were advancing in full force. “Indeed I saw their front between us and the Red Lion,” Stirling noted. He quickly issued orders.23

“The enemy advanced towards us,” wrote Major Mordechai Gist, the ranking officer with the Maryland battalion, “upon which Lord Stirling, who commanded, drew up in a line and offered them battle in true English taste.”24 Stirling posted his men in formal battle array and ordered them to face the enemy in the open. This time, it was the British who took cover behind trees.

Lightning from field guns and muskets flashed in the darkness. Quiet became din. The battlefield took on the jagged confusion of a dream. Rather than rush the American line, the British “began a heavy fire from their cannon and mortars,” wrote Gist, “for both the Balls and Shells flew very fast, now and then taking off a head.” For men who had never endured organized violence, the sudden decapitation of a comrade was a rude introduction to the hallucinatory world of combat. “Our men,” Gist added, “stood it amazingly well.”

They stood it and stood it. The concussions of British artillery and the zinging musketballs stripped the world of all safety. The deafening percussion went on hour after hour.

All of New York came awake to the desperate struggle that had erupted. As dawn brightened the eastern sky, Stirling rode up and down his lines, adjusting, encouraging. General Washington came over from New York—he could do little but observe from Cobble Hill, a high point inside the American fortifications. At nine o’clock, amid the din, Stirling’s ears picked out the firing of a single cannon. Could it be? Yes, the boom sounded a second time—from behind him. What could it mean?

An instant later—for Stirling, for Sullivan and Putnam, for Washington and the whole Continental Army—the veil dropped. The attack against Stirling was a diversion. While Grant’s cannon banged away at the American right, General Howe had marched his army through the darkness to a distant pass where the Jamaica Road went around the end of the American line. The pass, Howe noted, had, through “unaccountable negligence,” been left undefended. His men captured the five mounted sentinels stationed there and slipped around to the north of Sullivan’s men. They marched down the length of road that led straight toward the main American fortifications.

Now the whole tenor of the battle changed. The Hessians, who had been exchanging a sporadic fire with Sullivan’s men in the center, formed for an attack in earnest. The green-jacketed jaegers, German hunters, scrambled through the woods, firing with short-barreled rifles. The huge, brass-helmeted grenadiers came tromping forward, their drums pounding an angry tattoo. The Americans, accustomed to clean-shaven faces, had never seen the like of the fierce black mustaches the men wore. These fairytale giants from the German woods, smelling blood, thrust their eighteen-inch bayonets into any American flesh that came within reach. They had no mercy.

Caught in a vice between the Hessians in front and Howe’s infantry to their rear, Sullivan’s men threw down their muskets and sprinted to gain the relative safety of the fortified lines two miles away. Fear gave their feet wings. “The rebels abandoned every Spot as fast, I should say faster, than the King’s Troops advanced upon them,” General Howe’s secretary noted.25

Sullivan did what he could, which was nothing. “The last I heard of him,” one of his officers reported, “he was in a corn Field close by our Lines with a Pistol in each Hand.” He was captured by three Hessians.26

The American outer line collapsed. Lord Stirling, with his Maryland and Delaware regiments, stood alone outside the fortifications. They now faced the all-out attack of Grant’s brigade at their front, the Hessians sweeping down the ridge from the east, and General Cornwallis leading the British advance guard against their rear. Stirling “encouraged and animated our young soldiers with almost invincible resolution,” Major Gist wrote. Watching the action beyond the American fortifications, Washington was reported to have sobbed or yelled, “Good God! What brave fellows I must this day lose.” It apparently had not occurred to him or to Putnam to order these troops to retreat. Lord Stirling had been directed to repulse the enemy and he had received no further orders. He fought on.

Finally, pressed on three sides, Stirling saw that the only escape was through the marshy Gowanus Creek. He detached 250 Marylanders as a rear guard and sent the rest of his regiments toward the water. Wading through the tidal muck under fire, most of them made it across, emerging inside the American lines “looking like water rats.”

Sword in hand, Lord Stirling led his Maryland contingent in a sharp counterattack to the north against Cornwallis. Flung back, the Americans regrouped and tried again. And again. They came very close to breaking through and gaining the fortified line. Their commander, a soldier noted, “fought like a wolf.” 27

After five charges, Stirling saw that it was “impossible to do more than to provide for safety.” His men ran for it the best they could—all but nine were killed or captured. Stirling was cornered and forced to surrender. As his biographer duly noted, no one could have predicted that this amateur, “this overweight, rheumatic, vain, pompous, gluttonous inebriate,” would shine so in battle.28

By noon, the largest battle that would be fought during the entire war was over. It seemed to officers on both sides that the rebellion itself was finished. The Americans had been utterly defeated. William Howe had outthought, outmaneuvered, and outfought George Washington. Nathanael Greene, who had yet to participate in a battle, lamented his absence. “Gracious God! to be confined at such a time.” He suggested that the outcome “would have been otherwise,” had he been in command.29

And the cost. Captain Joseph Jewett lingered in agony from bayonet wounds to his chest and stomach—a day and a half later he was “sensible of being near his End, often repeating that it was hard work to Die.”30 Three hundred other Americans had been killed, hundreds wounded, and hundreds, including three generals, taken prisoner.

The rest of the bedraggled force was now trapped inside their perimeter. The victorious British and Hessian troops might have instantly overrun them, but Howe followed, a historian noted, “the dictates of prudence rather than those of vigor.”31 Sure of victory, he called his men back and began a classic siege. The cocky General Grant opined that “if a good bleeding can bring those Bible-faced Yankees to their senses, the fever of independency should soon abate.”32

* * *

With half his army trapped in a cul de sac, George Washington had full cause to despair. Yet he did not despair. He did not flinch. The next day, as the fine weather turned cold and rainy, Washington did the unexpected: he ordered two more regiments over to Long Island. The sight of 1,200 fresh men marching up from the Brooklyn ferry landing with drums beating did wonders for the morale of the weary army manning the fortifications.

The drenching rain developed into a cold nor’easter. The storm dampened the spirits of the soldiers, but the contrary wind kept the British navy from getting up the East River and cutting them off. American riflemen popped away at the enemy from the forts and from forward skirmish positions as often as their damp gunpowder would allow. The British began digging ditches that would soon bring their cannon within range of the forts.

By the following day, some Americans stood waist-deep in waterlogged trenches. Washington had not slept the past two nights. He displayed no anger, frustration, or panic. He thought out his situation and ordered men to confiscate all available boats along the Manhattan shoreline. They would be used, he let on, to bring more troops over from New Jersey.

In the late afternoon, with the boats assembling, he called a war council of his officers. Retreat was the only option. Washington was going to try to slip the army on Long Island, 9,500 men, over to New York. The move would test the nerves of every man in the force. As each regiment withdrew, the others would have to spread out to maintain the illusion of a strong defensive line. Down at the Brooklyn ferry landing, John Glover, a stocky, redheaded member of the Massachusetts “codfish aristocracy,” commanded a regiment recruited from rugged Marblehead fishermen. These watermen would row the army across an estuary churning with contrary currents.

As a drizzly darkness fell and the wind died, the silent evacuation began. Orders were passed in whispers; wheels were muffled; the men were warned not even to cough. The fishermen began rowing their makeshift ferries, the gunwales inches above the water. Over and back, over and back. Washington personally supervised the loading. Henry Knox directed his gunners in hauling and ferrying across almost all his critical cannon. For those left in the lines, the danger steadily grew. If the British got wind of what was going on, the men who remained would be instantly overrun and slaughtered.

Dawn came and hundreds of men remained on the Brooklyn side. Luckily, a dense fog formed along the waterfront and continued to obscure the movement from British eyes. By seven in the morning, all the troops had escaped. None had died in the effort. Washington stepped into the last vessel to cross.

An hour later, British officers appeared on the empty Brooklyn shore. They peered across in astonishment. Washington, who bore most of the blame for the calamitous defeat three days earlier, had pulled off one of the most delicate exploits of the war. But the escape could not erase the rout. British experience had bested American enthusiasm. “In general,” John Adams noted wryly, “our generals have been out-generalled.”33

The British were exuberant. Having easily triumphed over Washington’s amateur army in battle, they now had his troops on the run. Lord Cornwallis was sure that “in a short time their army will disperse and the war will be over.” Soon after the battle, British general Henry Clinton, who had devised the brilliant flanking march that had beaten the Americans, wrote home to his sister. He ended with that perpetual, poignant soldier’s cliché: he would, he assured her, be home by Christmas.