An Indecisive Mind

1776

Nathanael Greene was for burning New York City to the ground to keep it from falling to the British. Congress would not stand for such a move. After the devastating loss on Long Island, Washington had to decide whether to hold the city or relinquish it to the enemy. He saw the military logic of a retreat before a superior force. “On the other hand, to abandon a City, which has been by some deemed defensible . . . has a tendency to dispirit the troops.”1 He worried about his own reputation, noting that “declining an engagement subjects a general to reproach.”2

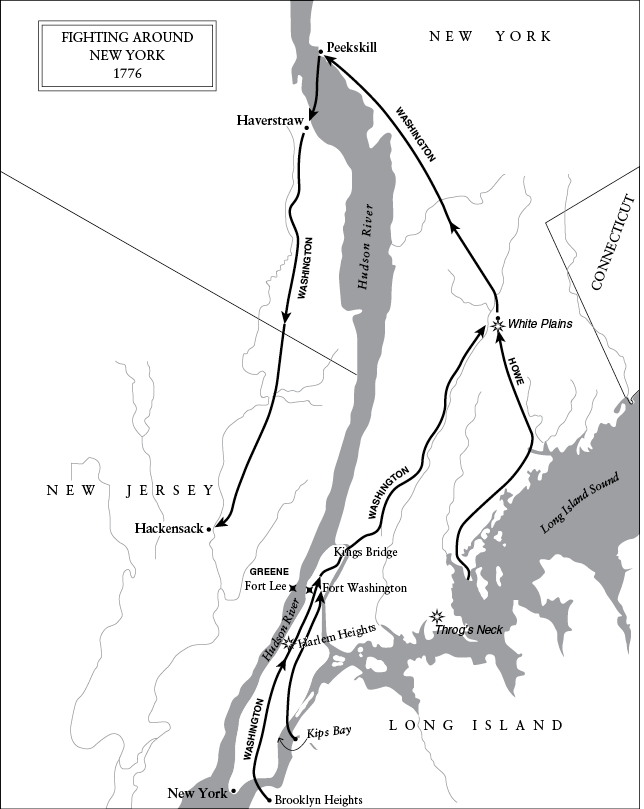

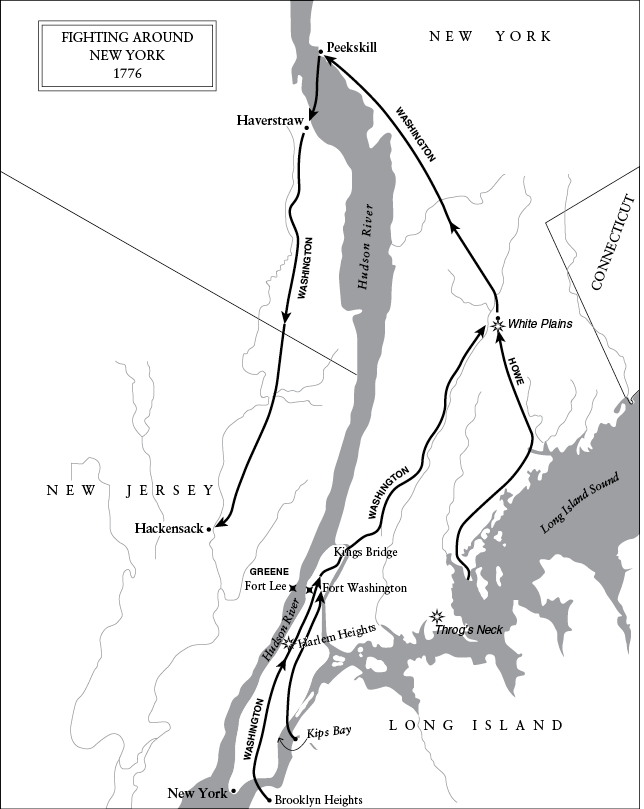

During the second week in September 1776, even as he tried to monitor the fraught events unfolding on the border of Canada, Washington admitted that his army had to clear out. He started the bulk of the men marching toward Harlem Heights, a defensible ridge across Manhattan Island ten miles north of the city limits.

Part way up the island, nervous, untried troops were guarding an inviting landing spot along the East River at Kips Bay. They watched as four massive British warships made their way up the river and dropped anchor two hundred yards away. They could count the black holes of seventy-four large cannon scowling at them from the ships’ sides. Crowds of British and Hessian soldiers were gathering on the opposite shore.

The next morning, September 15, these same recruits peered over their ramparts as the thousands of enemy soldiers embarked in a flotilla of rowboats. The late-summer day turned sultry and stagnant. Sailors began to maneuver the crowded boats into the river, pausing near the center of the channel. The defenders could make out the faces of their enemies.

“All of a sudden there came such a peal of thunder from the British shipping that I thought my head would go with the sound,” remembered Joseph Plumb Martin, one of the privates waiting in the shallow trenches the troops had dug to defend the beach.3

“So terrible and incessant a roar of guns,” another observer declared, “few even in the army and navy had ever heard before.”4

Cannonballs tore into the mounds of earth in front of the troops, lifting spouts of sand and plowing great gaps. The guns’ mind-numbing detonations deranged the defenders’ senses and shattered their determination to resist. They panicked. “The demons of fear and disorder,” Martin remembered, “seemed to take full possession of all and everything that day.”

The German and British invaders stepped ashore under a pall of heavy smoke without losing a man. “I saw a Hessian sever a rebel’s head from his body,” a British officer reported, “and clap it on a pole in the entrenchments.”5

Washington came galloping down from his headquarters four miles to the north. Five thousand of his men remained in New York City, along with tons of supplies and scores of heavy cannon. If the defenders allowed the British to march across the island and block the army’s retreat, the loss would be fatal. The enemy must be stopped.

“I used every means in my power to rally and get them in some order,” he reported to Congress, “but my attempts were fruitless and ineffectual.” This was an understatement. Washington’s usual tight control slipped and his “ungovernable passions” took over. He became a “harum Starum ranting Swearing fellow.” He screamed orders. He dashed his hat onto the ground. “Distressed and enraged,” an observer noted, he “drew his sword and snapped his pistols” to check the fleeing men. “Are these the men,” he shouted, “with which I am to defend America?”6 As advancing enemy troops came within musket range of the American commander in chief, Washington’s alarmed aides had to yank the reins of his horse to rush him to safety.

“I could wish the transactions of this day blotted out of the annals of America,” wrote a patriot officer. “Nothing appeared but fright, disgrace, and confusion.”7

Washington sent orders to hurry the evacuation of troops up the west side of the island. Israel Putnam, by means of “extraordinary exertions,” organized a hasty departure, forcing Henry Knox to leave behind some of his cannon. Fortunately for Washington, General Howe moved at his usual cautious pace. Rather than rush the advance guard across to the Hudson and cut the island in half, he waited until another nine thousand of his troops could be ferried across the East River. The delay gave Old Put the time he needed. The American troops managed to reach the safety of their lines at Harlem Heights just before night descended and the British sealed the largely empty trap.

Washington blamed the rout on the “disgraceful and dastardly conduct” of the troops. Others recognized that it was not the men but the officers who were to blame. “The bulk of the officers of the army are a parcel of ignorant, stupid men,” Henry Knox wrote to his brother, “who might make tolerable soldiers but bad officers.”8 He began to push for the establishment of an academy to train professional military leaders, a cause he would champion for years to come.

The loyalist residents of New York City welcomed the redcoats enthusiastically. Some carried British soldiers on their shoulders and acted like “overjoyed Bedlamites” at the return of legitimate authority to the city.

The day after the Kips Bay fiasco, a skirmish south of Harlem Heights suddenly flamed into a full-scale battle. The clash provided Nathanael Greene with his first taste of combat. After years of studying and dreaming about war, after listening to the roar of the battle of Long Island from his sick bed, he now found himself in the middle of a chaotic, nerve-jangling fight. He and General Putnam rallied their men. The British fell back and were soon running up a slope opposite the Heights, seeking protection under the guns of British warships on the river. Washington gave orders for his troops to break off the chase lest they should stray too close to the main British line. In the fight, they had killed or wounded almost 400 enemy soldiers, losing only 150 of their own men.

The Americans came back elated. For now, they had stopped running, had given the enemy a beating. “They find that if they stick to these mighty men,” Knox noted, “they will run as fast as other people.”9 Washington wrote of the engagement, “It seems, to have greatly inspired the whole of our Troops.”

For the next few weeks, the two armies stared at each other from lines that stretched across Manhattan. From Harlem Heights, the Americans watched New York City burn on September 21, the fire touched off by “Providence—or some honest fellow,” Washington noted. The blaze reduced nearly a quarter of the town to ashes. Daniel Morgan and some of his companions from the Quebec expedition, on their way to being exchanged for British prisoners, watched the inferno from ships in the harbor. They saw the towering steeple of Trinity church, erected in 1698 with the help of the pious pirate Captain Kidd, turn to a “pyramid of fire” before it crashed to the ground.

Washington now made the odd decision to hold his position on Harlem Heights. If the enemy were to land troops north of Manhattan and cut off the Americans’ escape route over Kings Bridge, the army would again be trapped. They could be surrounded and defeated or isolated and starved to death. Nathanael Greene, for one, wanted to get out: “Tis our business to . . . take post where the Enemy will be Obligd to fight us and not we them.”10

The burden of command weighed on Washington. “In confidence,” he wrote to his cousin Lund, “I tell you that I never was in such an unhappy, divided state since I was born.” He was, he admitted, “wearied to death.”

Desertions, expiring enlistments, illness, and battle casualties had cut his army in half since midsummer. After a brief hiatus, the violence resumed. On October 9, three British warships sailed up the Hudson River, straight through the barriers that the rebels had constructed in the water, past the guns of Fort Washington on the eastern and Fort Lee on the western heights. “To our surprise and mortification,” Washington wrote, “they ran through without the least difficulty.” Three days later, Howe landed troops on the mainland, threatening to trap Washington’s forces.

General Charles Lee had just returned from helping thwart the British attack on Charleston. His appearance relieved many in the army who valued his experienced opinion. Alarmed, he pointed out that remaining in Manhattan was worse than folly. The troops must withdraw north before the enemy cut them off. They had to start now.

A council of war agreed. The officers decided to abandon all but the narrow northern tip of Manhattan, which was safely dominated by the guns of Fort Washington. Lord Stirling, who along with General Sullivan had returned to the army in a prisoner exchange, immediately led an occupying force to White Plains, fifteen miles north of Manhattan.

On October 28, Howe attacked the Americans dug in on high ground near White Plains village. Fall foliage filled the limpid day with gold, vermilion, and bright orange. The British and German soldiers had seen nothing like a northeast autumn. Their own scarlet and blue coats added to the spectacle. Their polished bayonets glittered in the harvest-scented air.

The battle began with a thunderous bombardment. “The air groaned with streams of cannon and musket shot.”11 It ended with Hessians pushing the Americans off a nearby hill and chasing them through a forest of burning leaves. The British won, but endured 250 casualties, twice as many as the rebels. The Americans pulled back and awaited a renewed attack that never came. On November 5, the British withdrew. Where were they headed now?

Washington divided his army. General Lee would remain with seven thousand troops near White Plains, ready to react to British movements. Another four thousand men would guard the strategic Hudson Highlands to the northwest in order to prevent the enemy from moving up the river. They would also protect the ferry crossings essential to coordinating the American forces. Washington and Lord Stirling would cross to the west side of the Hudson and march two thousand men south, joining Greene’s brigade at Fort Lee. Washington suspected that New Jersey, and ultimately the capital at Philadelphia, were Howe’s targets.

* * *

Commanding Forts Lee and Washington, which straddled the Hudson at the north end of Manhattan, Nathanael Greene had anticipated his superior’s concern. He had directed his men to establish a string of supply depots on the road to Philadelphia, which ran south through Newark to Brunswick, then straight across the state to Trenton, which lay a day’s march from the capital. It was the type of initiative and foresight that heightened Washington’s confidence in the young general.

That confidence was about to be put to the test. The British had proven they could run ships up the Hudson past the guns overlooking the river. Howe’s army was now ranging north of Manhattan. Yet Greene still insisted that Fort Washington be held. He figured the British would never dare to thrust into New Jersey with an armed post at their rear. If they besieged Fort Washington, it would take them until December at the earliest to prevail against its high dirt walls and guns. If worse came to worst, Greene could easily ferry the garrison across the river.

Washington was not so sure. When more British ships slipped up the river in early November, he wrote to Greene, “If we cannot prevent vessels passing up, and the Enemy are possessed of the surrounding country, what valuable purpose can it answer” to hold the fort? Then he conceded, “But, as you are on the Spot, I leave it to you.” Greene was confident. “I can not conceive the garrison to be in any great danger,” he wrote back. “The men may be brought off at any time.”12

Within days, Howe was massing fourteen thousand troops around upper Manhattan. In response, Greene sent more men across the river from New Jersey, bringing the total American force around Fort Washington to 2,800. This was reckless folly, but Greene could not see it. The immediate commander of the fort, Colonel Robert Magaw encouraged Greene in his error. “We have labored like Horses and completed a Fort said to be one of the Strongest in America,” he boasted.13 A thirty-five-year-old bachelor lawyer from the Pennsylvania frontier, Magaw loved to fight. But like Greene, he had only been soldiering for a year. Both men consulted wishes rather than reality in assessing the situation.

On November 13, Washington arrived to look over the terrain in person. He would later speak of “warfare in my mind,” but he did not countermand Greene’s strategy. Two days later, catching up on paperwork at his headquarters in Hackensack, the commander received an urgent message. The British, under a flag of truce, had delivered Magaw a demand to surrender Fort Washington in two hours. If he refused, all the defenders would be put to the sword. Such threats were traditional intimidation tactics in sieges and were allowed under the customs of war.

Washington galloped the five miles to Fort Lee. He was starting to cross the river under a darkening sky when he met Generals Greene and Putnam returning. Magaw had refused to surrender. “Activated by the most glorious cause that mankind ever fought in,” the fort’s commander had written to Howe, “I am determined to defend this post to the last extremity.” There was nothing to do for the moment.

The next morning, Washington went over to the fort named for him, accompanied by Greene, Putnam, and Hugh Mercer. The fifty-year-old Mercer, a Scottish immigrant and physician, was a fellow Virginian and close friend of Washington, a comrade during the French and Indian War. While the generals were taking stock of the situation, the British began to attack American positions from three sides.

Four thousand infantrymen approached the American lines from the south. The loud, contemptuous Hessian colonel Johann Rall led a five-hundred-man regiment of grenadiers up the precipitous north slope of the heights on which the fort stood. Scottish Highland troops attacked from the east.

The four American generals had made their way to the Morris House, Washington’s former headquarters south of the fort. “There we all stood in a very awkward situation,” Greene later recorded. “As the disposition was made, and the enemy advancing, we durst not attempt to make any new disposition; indeed we saw nothing amiss.”14

Suddenly, enemy troops came rattling through the woods. The generals had to get Washington away instantly. Fifteen minutes later, the Morris House was in British hands.

At the north end of the heights, a regiment of Pennsylvania riflemen fired down at the German grenadiers who were scrambling up the steep cliff. They were backed by the fire of two cannon. A gunner’s mate named John Corbin stepped in front of the barrel to ram home a cartridge. The Germans fired their own guns from a nearby hill and killed him. Corbin’s wife, Margaret, who had celebrated her twenty-fifth birthday a few days earlier, stepped up to take his place. She was a child of the frontier, her father having been killed and her mother kidnapped in the raids that followed Braddock’s defeat on the Monongahela. Knowing the routine of the gunners, she helped service the piece until canister shot ripped into her breast and shattered her arm. Captured, she would survive her wound and receive a soldier’s pension.

As Corbin lay wounded, she watched the German grenadiers begin to emerge over the lip of the heights, driving the riflemen before them. Colonel Rall was known as “The Lion” for his ferocity. The Germans had suffered many casualties during the climb and were in a mood for revenge. The Americans ran for the fort. There an eighteen-year-old Connecticut soldier was moving down a passage with two comrades to defend an outer breastworks. “There came a ball,” he noted, “and took off both their heads, the contents of which besmeared my face pretty well.”15

Soon a white flag appeared over Fort Washington. All the defenders, 2,800 soldiers from Washington’s rapidly dwindling army, became prisoners. The British were surprised to see that many of them were old men and boys younger than fifteen. All were filthy and lacked military bearing. “Their odd figures frequently excited the laughter of our soldiers.”

Their fate was no laughing matter. Like other American captives, most would die in British hands. Some starved to death in excrement-layered New York churches and warehouses. The rest were packed into the hell of black ship holds and sent to Gravesend Bay, off Long Island, where disease and exposure finished them off.

* * *

“I feel mad, vext, sick, and sorry,” Nathanael Greene wrote to Henry Knox after the surrender. “Never did I need the consoling voice of a friend more than now.”16 Insecure by nature, he pressed Knox for news of how the loss was seen by other officers. Would Greene be sacked?

Washington was certainly upset. Some said he wept as he watched from the New Jersey shore. An aide recorded that he “hesitated more than I ever knew him on any other occasion.”17

“I am wearied almost to death with the retrograde motions of things,” he wrote to his brother Jack. “What adds to my mortification is, that this post after the last ships went past it, was held contrary to my wishes and opinions.”18

What? It was Washington who had approved the dispositions of his inexperienced subordinate. A military leader does not express himself in wishes and opinions. He gives orders. His Excellency was still learning.

Having taken Fort Washington, General Howe moved with uncustomary dispatch. On a rainy night three days after the surrender, he sent five thousand men rowing across the Hudson River on flatboats. It was the first independent command for Lord Cornwallis, the most enterprising officer in England. This thirty-eight-year-old son of privilege had joined his majesty’s army at seventeen and was prized for his competence. He landed his force at the base of the sheer Palisade cliffs on the west side of the river. His men trudged up a steep, four-foot-wide trail, expecting a fight at the top. General Greene had neglected to station guards there. The British winched eight field guns up the cliff. They were not discovered until daylight.

Fort Lee, more of an armed camp than a fortification, was doomed. All Greene could do was to order an instant retreat. The British marched into the fort to find fires burning, cooking pots bubbling. They found hundreds of tents, cases of entrenching tools, and scores of cannon. When a German officer recommended a spirited attack against the fleeing Americans, Cornwallis replied, “Let them go.” The beaten, disintegrating army of rebels was not even worth pursuing.

* * *

Now came the great retreat that Washington had feared. First to Newark. Then to Brunswick, near the southern tip of Staten Island. Then across the narrow waist of New Jersey toward Trenton. Washington’s iron determination became the army’s backbone. “A deportment so firm, so dignified, but yet so modest and composed,” wrote eighteen-year-old James Monroe, “I have never seen in any other person.”19

Cornwallis, under orders from Howe, followed Washington across the state without trying to crush his force. Washington called upon General Lee, still camped near White Plains, to bring his troops and help defend Philadelphia. Lee, who claimed he “foresaw, predicted, all that has happened,” failed to respond.20 In the midst of the army’s worst catastrophe, Washington now faced a crisis of leadership. His second in command, who led more troops than Washington himself, was heeding his own notions about the proper way to execute the war.

Lee’s resistance to Washington was based on more than mere vanity. He was concerned about his troops, many of whom lacked shoes. Politically more radical than most of the other military leaders, Lee believed in a war fought by militia drawn from an “active vigorous yeomanry.” He was sure that “a plan of Defense, harrassing and impeding can alone Succeed.” The army, he thought, should keep a presence in New Jersey to rally local militia and reinforce their efforts. If Washington abandoned the state, loyalists would reign.

Others were hinting that Lee, not Washington, should be in charge. On November 21, Washington’s secretary and aide Joseph Reed wrote to Lee, “I do not mean to flatter nor praise you at the Expense of any other, but I confess I do think that it is entirely owing to you that this Army & the Liberties of America . . . are not totally cut off. . . . You have Decision, a Quality often wanting in Minds otherwise valuable.”21

Washington continued to urge Lee to hurry forward with his men. In deference to the style of the day and to Lee’s superior military experience, he did not issue a flat-out order. Lee continued to resist.

A week later, Washington accidentally opened a letter from Lee to Reed. “I . . . lament with you that fatal indecision of mind which in war is a much greater disqualification than stupidity,” Lee wrote. He listed some excuses for his failure to comply with Washington’s request. He asserted that he would set his troops in motion when ready because “I really think our Chief will do better with me than without me.”

The word “indecision” must have bitten Washington as deeply as the evidence that his trusted secretary had criticized him behind his back. Indecision, his indecision, had cost the army at every step.

The recalcitrant Lee was writing in private letters that “the present crisis” required a “brave, virtuous kind of treason.”22 He stationed his force in Morristown, directly west of New York and fifty miles from Washington, who was now at Trenton. General Horatio Gates, freed from danger by Arnold’s sacrificial battle at Valcour Island, had brought some of his troops to reinforce Washington’s men. He received an invitation from Lee to join forces and “reconquer . . . the Jerseys.” It was Gates, his former comrade in the British army, who had urged Lee to come to America. Like Lee, Gates thought highly of militia. He was not, however, prepared to subvert the chain of command.

On December 8, Washington sent Lee an unambiguous order to advance. “The Militia in this part of the Province seem sanguine,” Lee replied three days later. “If they could be assured of an army remaining amongst ’em, I believe they would raise a considerable number.”23

The situation in New Jersey was actually deteriorating. On November 30, the Howe brothers had offered a “full and free pardon” to anyone who would take an oath of allegiance to the king. Thousands, afraid of losing their property, hurried forth to swear. Loyalists began to take reprisals on patriot neighbors.

British and German troops contributed their own savagery. Nathanael Greene, in a letter to Caty, claimed that “the brutes often ravish the mothers and daughters and compel the fathers and sons to behold their brutality.” The rape of girls as young as ten was reported.

The news grew even darker. Howe had sent General Henry Clinton to Providence to secure that important port against rebel privateers. He had taken the city easily and now dominated Rhode Island. During the first week in December, Washington, ceding New Jersey, transferred his army to a defensive position on the west bank of the Delaware River, which divided that state from Pennsylvania.

Prospects were bad. Two thousand of Washington’s troops, their enlistments having run out, had limped off toward home. Another three thousand men were too sick to report for duty. At the end of the month, when almost all enlistments would expire, the Continental Army would effectively dissolve.

On December 13, General Lee was still refusing to join Washington. That morning, ensconced with a small guard at an inn several miles from his camp, he was finishing up some paperwork. In a letter to Gates, he facetiously referred to “the ingenious manoeuvre of Fort Washington.” He went on: “Entre nous, a certain great man is damnably deficient. He has thrown me into a situation where I have my choice of difficulties.”24

Suddenly, a squadron of British cavalry came pounding up to surround the inn. One of their officers, a twenty-two-year-old subaltern and military prodigy named Banastre Tarleton, threatened to burn the building and those in it if Lee refused to come out. Lee, still in his slippers and night clothes, surrendered.

Lee’s capture delighted the enemy. A Hessian officer said that Lee was the only rebel general they had reason to fear. “This is a most miraculous event,” Tarleton wrote home to his mother. “It appears like a dream.” He was sure his coup would put an end to the campaign.25

For Washington, the surprising turn of events may not have been entirely unwelcome. “Unhappy man!” he wrote, “taken by his own Imprudence.” His back against the wall, he had little time to dwell on the loss.

Nathanael Greene, who had spent the autumn learning the hard, bloody lessons of being a general, clung to a shred of optimism. “I hope this is the dark part of the night,” he wrote home to Caty, “which generally is just before day.”26

Washington also dared to hope. Perhaps the British were a bit too overconfident. Perhaps his men could still pull off a counterstroke. Perhaps he could then hold out long enough to recruit a new army. Perhaps. If not, he wrote to Lund, “I think the game will be pretty well up.”27