chapter 7

“The Transition” Young Adults Returning Home

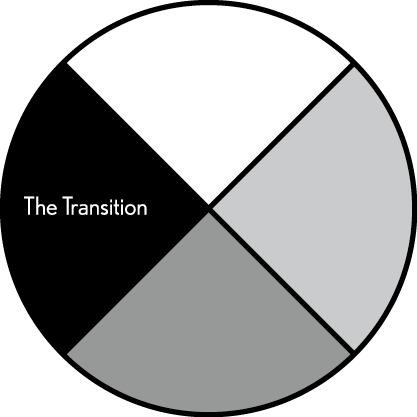

The journey continues in the western door with the transition to adulthood (see Figure 9). In the west, this is a time for maturity and reflection. This chapter opens with a voice of a survivor as she transitions from the school to her outside life. I then briefly describe some of the nutrients such as the marriage ceremony, parenting teachings, and additional ceremonies that prepare adults for life. These nutrients nourish them with the knowledge and when to ask for the ceremonies, to remain in balance. I then offer some of the experiences of the survivors as they transitioned from the regimented school life and survived. Finally, despite efforts to diminish the Anishinaabe mino-bimaadiziwin (the way of a good life), I discuss how these individuals found creative ways to work, raise families and nourish the Anishinaabe life force energy or mnidoo bemaasing bemaadiziwin within them.

Well I think at that time I was used to being on my own. When I left the school for the summertime, I actually took care of my older brother, fought for him, helped him get on the right bus, helped him get off. He eventually quit going to residential school before I did so he functioned just fine without me but when we’re together, I did the thinking and so I just kind of went on that way.

I remember the first time that I went to a home that I was an alien in and so I wanted to move out of there so the first summer I was out of the residential school and I made a decision to move out and I moved into the YWCA. Now, because I was only 16 I had to get permission from the Social Services of the State of Michigan to live on my own otherwise I’d be called a runaway so I went through all that and they gave me permission to stay at the YWCA and they put me in a room all by myself in a section of the building where there was nobody else. It was kind of like near the swimming pool and I felt so alone there and that was the first time that I was ever alone you could say and it made me stop and wonder whether I would survive in a world that I had never ever really lived in. I was used to so many kids in a room that we kind of nurtured one another. We didn’t have an adult nurturing us but we had each other and so I really missed my family from school and I thought well I survived residential school, I’m going to survive this and the first night I had a lot of trouble sleeping but, after that, I didn’t then so I’d been living, not living on my own cause two years later I was married and started having kids but, for those two years I lived on my own and it was very strange. (Susie, October 2, 2010)

As young adults the former students were now experiencing their first taste of freedom. While the freedom was sweet, very few survivors had a place to go, or a place to fit in. Imagine the loneliness of being at the Young Womens’ Christian Association (YWCA) with no friends. This contrasts significantly to the Anishinaabe way of life of being welcomed into a family circle, a clan, a community and nation.

Figure 9. The Transition

Please note that the colours that make up the Medicine Wheel are a crucial part of its extended meaning. The versions used in this text use the following colour formation: the North quadrant is white, the Eastern quadrant is yellow, the Southern quadrant is red, and the Western quadrant is black. The Medicine Wheels presented in this book have been approved by the Elders consulted for this work.

Anishinaabe Mino-bimaadiziwin

(The Way of a Good Life)

The next development of Anishinaabek maturation includes the teachings of the role of becoming both a marriage partner and a parent. We must participate in these ceremonies to make us aware of the responsibilities of what is required to be successful partners and caregivers. Elder Doug Williams describes the process of the marriage ceremony as follows:

… when the two partners have picked each other to marry, or the family have picked them for them. Just before that—they have a ceremony that we would call today a wedding ceremony. In the old days it was called wiijiiwaagan that means that they are going to be joined. They are going to be joined with somebody they are going to be walking with. Now when that happens then for sure the men then get together with the young man who’s going to get married. The women get together with the woman who is going to get married and the men go through the teachings about how to treat women and also the teachings of sexuality right so that’s basically in a nutshell what happens.1

According to Basil Johnston, the marriage ceremony had a pre-marriage waltz. The first step is prudence, then acceptance, judgement, loyalty, kindness, and finally, the ceremony. The ceremony begins with the young man asking the woman’s father for permission. Once accepted, the ceremony is performed by the grandparents. The young woman must be ready to marry and possess skills needed to maintain a home such as cooking and sewing. During the ceremony, the grandmother tells stories and the hems of their marriage coats are sewn. Ritual words are spoken followed by feasting and the playing of games.2

The Anishnabeg word for the relationship between a man and a woman was “weedjeewaugun”3 meaning companion—a term which referred equally to male or female. There was no distinction in sex: no notion of inferiority or superiority. More particularly, “weedjeewaugun” meant Companion on the Path of Life—“he who goes with” or “she who walks with.” For both men and women, a companion was someone to walk with and be with through all aspects of life and living. Such was the notion of marriage: the taking of a companion. It is the strongest of bonds.

For the Anishinabeg, a woman’s worth was not measured by a lithe body, an unblemished complexion, full breasts, or sensual lips. How well she cooked, how well she sewed—or even nature of her temper—were the things that counted in a woman. How many deer or fish he could find his family, and how frequently he could provide them, were the standards for a man.4

Part of what makes us Anishinaabek is the roles that we are assigned as human beings. As adults we are also assigned positions of authority, whether we agree or not. Learning the responsibility of a role is part of the maturation process. As Anishinaabek people it was our custom to obtain these responsibilities through rites of passage; for boys, it is the big fast. For the girls, it is the “Walking Out Ceremony,” and for women, the “Full Moon Ceremony” among other important rituals. Since the children were taken off and put into residential school, these roles and responsibilities were never rooted in their psyche. This situation contributed to their roles being unfulfilled and further resulted in broken relationships.

The Transition

When the students left residential school some were still very young and continued on in school in their community. Others left at age sixteen and some eventually graduated and/or apprenticed at another institution. To be sure, many of the former students no longer had any conception of birth family or community (Susie, October 2, 2010), and Alice Blondin-Perrin, a survivor of St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic Mission School at Fort Resolution, Northwest Territories said “when I was in residential school, I did not even know what a family unit was.5 When they returned home they felt like aliens in their own home (Susie, October 2, 2010) and community (Patrick, October 2, 2010).

There was a lot of residential school residue; the former students were angry about their traumatic experiences. They felt like no one cared about them. When they changed, so did their behaviour. They became guarded, untrusting, unable to count on anyone (Sylvia, October 3, 2010). They took these behaviours with them into their adult world. What emerged from the compartmentalizing of pain resulted in unacknowledged and unresolved anger. One survivor said that there were men survivors that were so mad at their family and the government that they never reconciled with anyone, but some men at the end of their life might reconcile with themselves (anonymous communication). Elder Shirley Williams commented, “a lot of survivors died due to unresolved anger.”6 Another survivor said:

I say you should go to A.A., they’ll tell you how to get rid of your garbage, said you’ll have to take it all the way to the dump, you know, to get rid of it, you know, you don’t have to carry it all your life. That’s what I like about A.A. It’s my lifesaver; it’s my support group. It’s been very good to me, showed me how to live a better life, a forgiving life, a peaceful life, serenity, peace, no more anger. It pops up, but I know how to get rid of it, anger, no more fear, you know, that’s why that fear part, it used to scare me if anybody knew about my past, I would be afraid. I didn’t want to dig into that but now the more I talk—I don’t know how many people knew about my sexual abuse. I carried that for 50 years I wouldn’t let anyone know. (Leonard, June 9, 2008)

When I interviewed Leonard, it was important to him that his story needed to be told. He revealed to me that he was raped by two students at the Shingwauk residential school. He had also given his testominal before the Indian Residential School Independent Assessment Process because he felt it was important for the truth to come out. Leonard felt it was freeing that the truth be known and he made this decision so that it may be easier for other males to disclose.

Further, since the former students had never been taught to make decisions and were now free to do so, some lacked the confidence to believe in their ability to make choices, or feared doing so. Others, on the other hand, relished making their own decisions and felt empowered. Many of the former students feared authority and zhaaganaash people. As one survivor recalled her feelings as a student:

I learned that white people were not all bad and out to harm me. In fact, they were very nice to me. This gave me the courage and my self-confidence grew. I didn’t feel like such a wounded bird. (Geraldine, October 7, 2010)

Most of the residential school survivors I interviewed returned to families that were fractured or broken within their community. As one survivor said:

I had to learn to cope then and I just wrote some thoughts a couple of weeks ago about the things that we felt as former students and one of the things that I wrote down was—when we came out of residential school and I’m sure that this is multiplied by thousands, we had no conception of our birth family and conception of community—the way it used to be. Now there were a lot of kids that went home to happy families. Families that wanted them in the summertime and things like that, but there were also many families that were broken and I know from experience that families on reserves are fractured. They don’t do the—they don’t take up the responsibility of their position in other words, the mothers aren’t mothering, the brothers aren’t brothering, and aunties and uncles have bypassed their jobs too and of course the grandmas and grandpas they’re around, they seem and try and nurture but there’s a lot of them that don’t either so I think that was hard for me—was not necessarily at the school and yet it was really a part of the school. (Susie, October 2, 2010)

Some former students who returned to their communities felt they no longer belonged to their home community or First Nation. “Yeah, we didn’t fit in when we came back because we weren’t part of a family. We were just two kids that were added to the community” (Patrick, October 2, 2010). Another survivor told me that when he left residential school, he went looking for his mother. When he found her, she didn’t recognize him. This situation reminded me of the part in the movie, It’s a Wonderful Life when George Bailey goes to his mother’s house and he asks, “Mother don’t you know me, it’s George, I’m your son” and she responds, “I don’t have a son.” This same student, feeling rejected and abandoned by his mother again, ended up marrying a woman several years older than him because he was looking for a mother.7

Although some former students were able to maintain their language, others lost their language while in residential school. As one survivor said:

All the family in Detroit invited us over to visit them. They lived by Brigg’s Stadium and we couldn’t talk to them and they were mad at us probably thought we were standoffish. They didn’t know that it got beaten out of us. It took a long time for us to discuss that—that’s what really, really angered them. There was a nice clique of them in that area by Brigg’s Stadium on Michigan Avenue. They were very disappointed in me and kind of—after that we didn’t associate any more. (Patrick, October 2, 2010)

Many of the survivors did not return to Walpole Island or their home territory. This period is seen as a transition time when they had to make their own decisions rather than have residential school staff make decisions for them. Even this arrangement was problematic for the young adults. Many students only changed their regimented lifestyle from one institution to another. Three of the males I interviewed joined the military. One said enlisting in the military saved his life:

After a while I got a notice—the F.B.I. came to my house one time. They wanted to know why I didn’t register for the draft. I told them, “well I’m going back to Canada, and I’m going to Walpole tomorrow.” They said, “Well before you go, go down to the register.” Of course, when the F.B.I. comes to your door knocking, it scares the heck out of you, anybody would, so I was scared so I went and registered, signed. About six months later I got drafted cause I used to go back and forth from Walpole to Detroit you know. I’d stay over here a couple of weeks, couple there, couple of weeks, a week, a day, whatever, a month and I get this notice in the mail go down to the certain selected service board, and we want to talk to you and that was the end of that, then I was in the army.

That was a big turning point in my life I think, otherwise I would have made a criminal running the streets of Detroit. I would have wound up in Detroit. When I look back in hindsight that was really a good thing that happened that I got drafted in the army and taught me you know to obey and do things. I went to boot camp. I went to Texas for boot camp. I went to Germany for 18 months. All that was good in a round about way. Good came out of that for me. (Leonard, June 9, 2008)

One survivor joined the United States Marine Corps at 18 and later the United States Air Force. He served in Korea, did his basic training and eventually made sergeant. For him, the military allowed him to do a lot in his life. Once asked by an interviewer about his feelings about being at Shingwauk Indian Residential School, he contributed this:

A guy asked me to describe my feelings about Shingwauk and the best thing I could think of was—I was in the Vietnam War and I was in Vietnam three times. Once when I was a Marine and twice when I was in the Air Force and several times I come close to dying and that didn’t seem to bother me too much. I did think about it. But I told this interviewer, I says, “I was in two wars in my life and I enjoyed Vietnam much more than I ever enjoyed the two years in Shingwauk.” (Vernon, October 2, 2010)

As young adults, former students of the residential schools carried within them a different set of values and learned habits that they were forced to uphold as residual from that era. Unable to trust, many of them carried anger, which is understandable in this horrible situation. Many were loners, always on their guard, and ready to do battle. Many students had not learned their traditional ways of knowing or ways to deal with their unresolved anger through ceremony or other means to reconcile their feelings. It was pointed out to me by two survivors, that the earlier the child was taken to residential school, the more adversely affected their later adult life would be (Geraldine, October 7, 2010). Because the students did not experience any affection or emotional support from the staff, they would find parenting a challenge. This is a big issue and drawback for generations of children who were born to survivors.8 One student remarked:

My first baby died and, my second baby, he was born in 1953. My mother raised him because I didn’t think anything about leaving, leaving my children because I was left, like when I was nine months old, my grandma told her to go work in Detroit and she left me. I didn’t know I was abandoned. (Una, October 3, 2010)

Seeking Employment and a Sense of Place

Many of the former students were not only challenged to find a sense of place but also employment. Edmund J. Danziger, Jr. (1991), a professor of history at Bowling Green State University in the United States, describes the history of settlement in the Michigan area as robust because of the cession treaties.

In the nineteenth century the expansion westward of many white farmers forced Indian cessions of vast land holdings. Ultimately they were confined to 226 reserves across Canada, where aggressive agents employed many of the same methods used by the BIA [Bureau of Indian Affairs] in Michigan to destroy traditional Indian cultures.9

As a result, the ensuing consequence was that poverty and unemployment were rampant on the reserves and it was no different at Walpole Island. The people of this territory suffered the same fate of chronic unemployment and chronic poverty and resolved that there were no jobs on the reservation and the alternative was to starve.10 By the 1970s, the unemployment rate was 60 percent prompting Walpole Islanders and former students of the residential school to migrate to where they could get a regular pay cheque. Since Walpole Island is located just across the water from Detroit, Michigan, this city proved to be a starting point for a number of the young adults who left residential school. Detroit had a large Indian population at the time and was a bustling metropolis. Jobs were a big draw, and many of the former students worked in Detroit. Some started working at a very early age as these two survivors illustrate:

I lived in Detroit then, that’s where I went after Shingwauk. My mother moved to Detroit during like wartime stuff. Plants were busy. My stepdad was making pretty good money—good money I think my sister said at that time, so that’s where we went. We ended up in Detroit. (Leonard, June 9, 2008)

I was 13 then she gives me a job where she worked. She was doing housework across the river and the guy phoned and said, “I’ll give you work” so I was raking grass, cutting grass and all that, leaves, whatever. I even put up a garden for him but anyway that fall he took me down to Detroit and started working down there. He asked me, he says, “Come on down, I’ll give you work” so anyway I went down there when I was thirteen and then started working for him. I stayed with him for about—probably about five years and he paid me cash cause he couldn’t put me on payroll being underage and from then I started working, never was without a job, never. (Eric, October 7, 2010)

Some survivors worked in the auto plants, one worked in a restaurant, another worked for the state, and one was a die and toolmaker. Other former students went into construction and one survivor reported that he was an ironworker. Edmund Jefferson Danziger, Jr. further writes that because of the bulging Native American population, services were stepped up to address the increasing needs:

Innovative services also rested to a degree upon Detroit practices and institutions established before 1970: Indian personal networks of family and close friends, the bar culture, native neighborhoods, close reservation ties, and the venerable NAIA.11 By the early 1980s, after a decade of heady revivalism, an extensive Indian social-cultural infrastructure had thus evolved.12

Love of family is an important factor in the survivors’ lives. Many of the female former students got married, had children and were full-time caregivers and stay-at-home mothers. One survivor maintains that he has an enormous family because he wanted to be surrounded by love and lamented that:

Yeah, well that was one of my things when I left school. I don’t want to ever treat anybody the way I was treated. So that’s where all the love came in for kids and family I guess, that’s why we had a big family. (Eric, October 7, 2010)

Most of the survivors never spoke about their time at Shingwauk or any of the residential schools or about the trauma suffered while there. As a characteristic of Anishinaabek people, we think deeply before we act by using our observational skills. The students by nature would remain silent as they were not allowed to speak their language and they did not know English. They would not talk about the experience of residential school because of the trauma. Some of the former students buried themselves in their work and one survivor admitted:

I got a job at the Indian agency and I worked for the feds off and on and I got to be Band Administrator one time so it was a necessity for me to work because I couldn’t just sit around and do nothing for a long time. It was tough trying to blend back with the Band. The people of the Band here—when we were up at Shingwauk, it was very difficult and still very difficult for me to have friends because I don’t make friends very well without losing that friendship. (Patrick, October 2, 2010)

Other survivors became community leaders. For example as one survivor said:

You can see it in a lot of them, for one thing a lot of residential school children ended up going back to their reservations and becoming leaders on those reservations. I noticed that when I came home from the military. I got a few calls from different places and these people were councillors, and chiefs and police officers, things like that . . . But the ones, the ones that did make it became the leaders, they still had some problems about the school—I can’t really put a thumb down on exactly what their problems were but you could tell that they did have problems. Sometimes in a group we would talk about it and there were a lot of tears that period of time and I was—I became emotional seeing people that I went to school with, with so many problems and I didn’t know how I could show them or help them deal with it. I think a lot of my anger was taken out of me because of the things that I did while I was in the military. (Vernon, October 2, 2010)

As adults, the survivors worked hard and in return their adult children, the second generation, became hard workers.

I once asked my daughter, “Why are you guys such hard workers?” All six of my children work very hard and they may have other bad qualities, but they are all very hard workers and when I asked that child, she said, “We saw you working mother, so we just thought that was the thing to do.” Now my grandchildren don’t have that but my children do and so I see that in all the other families whether it be just a homemaker or whatever it is. (Susie, October 2, 2010)

Nurturing the Anishinaabe Life Force Energy

or “mnidoo bemaasing bemaadiziwin”

As Anishinaabek we are born into a set of relationships, a family, a clan, a community and nation. In this case, First Nations children were taken and placed in residential schools and while there they created substitute families. When they left residential school many found themselves alone; unable to return to their original family or original territory. Having never gained the Traditional Teachings from the Elders or the rites of passage, they lost their role and their identity in who they were supposed to be. Now they had to relearn to think, learn how to make decisions, relearn how to eat and how to live on their own. They needed to go forward without any guidance from anyone.

When you begin that path there is no—you really don’t know who you are in that respect. You mature, play with your child then you go out and you wander. You’re youthful. You look for a partner and so on until after that then you begin to know your truth . . . that energy is a combination of you as a physical being and as a spiritual being . . . 13

As previously stated, those two faces come together.

There is foreignness in being alone, as the essence of being Anishinaabek is through relationship. For these survivors, their art of strength, their Anishinaabe life force energy or mnidoo bemaasing bemaadiziwin was found in relationship: family, work, and/or military. Recall that a sense of belonging was key to feeding the survivors life force energy or mnidoo bemaasing bemaadiziwin. Other survivors I interviewed found family in work or military relationships. For example:

He says “I can get you a job doing trade work on cars” so well same thing again I’d quit over here Friday. I worked over here, two years and two months I think in Algonac then I went to Detroit, same thing, I’d quit Friday and started working over there Monday. I kept working, work, work—like I said there was plenty of work and that was about 1952 I think but I met her [motioning to his wife] in ’49. I think we went down—they could of had me for kidnapping cause I took her across the border, she was under age. We snuck away so anyway I was always working. There was a lot of work then I worked for that fellow for about 20, about 27 years altogether down Detroit off and on, like two years here, two years at Plymouth, about a year and a half in General Motors then he wrote me about three letters and the last letter he wrote me—”I guarantee you a lifetime job.” Hey, that sounded good so I went and talked to him.

Then I worked 23 years steady with him until the boys took over. He died—passed away so that broke that lifetime job. What his sons figured—I guess and after he died, the way he used to run business was the bigger contractors they’d subcontract, subcontract maybe they ended up about three, four subcontractors and before he got the money to his office that’s how long it took about a year and he had the bigger wheels Chrysler, Kelsey-Hayes, Great Lakes Steel, McLeod Steel, all those big companies down there that’s how he ran it but when the grandsons took over everybody else 30, 60, 90 day basis and they had to pay right now, a lot of the companies just dropped them just like that, and the company was going bankrupt so they laid me off. Let me see in ’75, I think or ’74 somewhere in there, laid me off down there, working on.

There’s a fellow here Jim T. was a water works—I don’t know I don’t think he had no title at the time, but anyway he come over on a Saturday and needed someone to help him so I said, “Yeah, okay”, “can you drive a truck?” “yep,” “a tar back hoe,” “yeah,” I drove truck for the R.S. Company for about eight years on the city there and I was dispatcher for about five but anyway we worked on a Saturday—put in a water line helped Jim with that and then so he said “I got another one Monday, can you come over Monday?” “Yeah, okay.” Albert was the boss and he said, “Eric, I need a truck driver,” he says, “could you drive for a couple of weeks?” and I said, “Sure, sure” okay so I drove a truck, dump truck so 25 years later and I’m still there now that insurance policy over here 70 and out so I had to get out so that was all the work. (Eric, October 7, 2010)

In the same vein, another survivor described her work life:

The goodness and kindness of people in my everyday life really helped me to blossom as a human being. From a very early age my goal was to be a nurse but because I dropped out of school that was not possible. My career has been working as a receptionist, bookkeeper, and supervisor and finally, as an ophthalmic assistant for doctors in Sarnia and they all were very wonderful people. I have been fortunate in my life to have a loyal loving husband, six very dear children, seven delightful grandchildren and seven treasured great grandchildren. My choices guided by the Great Spirit served me well. (Geraldine, October 5, 2010)

Another survivor recounted his experience in the military:

I joined the Marine Corps when I was eighteen, just after I turned eighteen and a lot of people said “Oh they’ll never take you—they’ll never take you, you don’t—you’re not smart enough for—you didn’t go to school” but during that time—during that period of time, they had a war going on in Korea and they needed a cannon fodder so they took me. And, I guess I wasn’t so dumb after all. I made sergeant where a lot of people didn’t . . . (Vernon, October 2, 2010)

Acceptance into a family was paramount to the survivors as they craved a sense of belonging. As young ones some had had the happy experience of returning to Walpole Island and becoming a part of a combined family while others felt rejected and alien from their birth family. As the latter may have been the case, some survivors sought out substitute families and lifestyles. Some embraced alcohol while others became workaholics. One survivor, after many years of drinking joined Alcoholics Anonymous as his new family. Others tried to pick up the culture again. Some also embraced organized religion. Many had to learn how to like themselves and relearn how to live a healthier way for the rest of their lives. They knew that they had to do something. One survivor remarked that:

There was nowhere to go, no one to talk to at that time and I thought well I got—I got a life to live. I have family and stuff and I want to change all that. I said I don’t want to be living like I did at the residential school. I want to change that and I can you know so what little I started to do is find myself—what am I doing that’s going to console other people. (Gladys, October 9, 2010)

However, what she found from other survivors was that “they said, ‘I don’t want to hear it’ and I thought geez it’s something that happened in your life and they’re always bitter. They’re bitter all the time” (Gladys, October 9, 2010).

The Shingwauk Project in Sault Ste. Marie facilitated the coming together of the Shingwauk Family for sharing, healing and learning.14 All of the activities—for example reunions, healing circles, publications, videos, photo displays, curriculum development, historical tours, and the establishment of archive, library and heritage collections—were in keeping with the original vision of Chief Shingwauk in providing education for the Anishinaabek people, while maintaining their traditions and culture. But most important was reclaiming their identity as Indigenous people and recovering the most sacred: the language, ceremonies, and Indigenous knowledge.

The former students had worked to transform the site into an inviting, loving and safe environment. They came to realize how much the school experiment had affected their lives. For the Shingwauk survivors, by again becoming part of the Shingwauk Family, many of their needs were fulfilled. They were accepted back into their family, they gained a sense of belonging and made a commitment to this community as in essence their connection and conception of community had been restored (Leonard, June 9, 2008; Patrick, October 2, 2010; and Susie, October 2, 2010).

As the survivors transitioned from young adults into their later years, what was paramount for them was to feel a keen sense of belonging. Getting married, finding work in a community or joining the military service accomplished this life purpose. Many survivors made a decision not to allow their life force to be destroyed. They found ways to move forward; each doing it in their own way. Some returned to their traditional ceremonies, some found healing and relationships through Alcoholics Anonymous, and some waited to see how others fared before starting their own. To me, a healing journey is a lifelong process that encompasses many layers of growth and understanding.

Even though the coping and survival skills learned at residential school numbed their feelings, their hearts were intact with the values and the teachings of the Seven Grandfathers as witnessed by their lives in present day. In the next chapter we will discover the many ways in which survivors chose to live out their later years and what responsibilities they embraced and challenges they overcame in reclaiming their spirit and becoming cultural warriors within their lives.