Asking the right questions at the right time is grounded in scholarship and intuition, and equally important is addressing those questions to individuals who know how to answer them. This progression is the starting point for an equally simple paradigm—teamwork, which often begins invisibly, but inevitably becomes truly useful. I am deeply appreciative and grateful toward these individuals and institutions that helped with this lengthy process.

Martha Riley, librarian at Washington University School of Medicine, Bernard Becker Medical Library, Rare Book Department, provided extensive assistance on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century medicine; Philip Skroska, archivist from the Rare Book Department, for his suggestions regarding the endless reels of medical microfilm. Of equal weight, and what I have come to claim as my alma mater, is the Missouri History Museum. Since 1976, persons from this revered institution have assisted my research, and I thank Emily Troxell Jaycox, Molly Kodner, Dennis Northcott, and Carol Verble. The museum's library staff, Edna, Jason, and Randy, have given loads of time searching through the shelves.

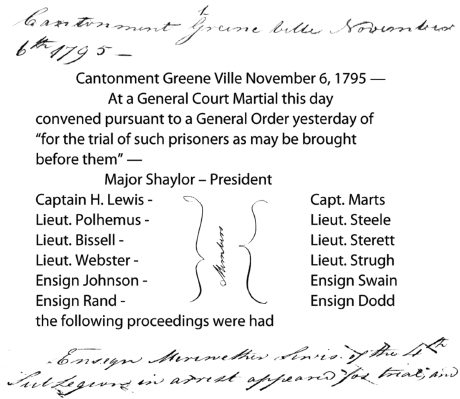

I am especially grateful to Daniel N. Rolph and David Haugaard from the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, whose extensive holdings on Gen. Anthony Wayne also included the original 1795 Meriwether Lewis court-martial proceedings. I am equally appreciative to Charles Wise and Rhonda Chalfant from the Pettis County Historical Society and Museum in Sedalia, Missouri, for allowing me to access Dr. Antoine Saugrain's medical ledgers and to photograph the pages of Meriwether Lewis's malarial treatment. I am also indebted to Sue Presnell from Indiana University's Lilly Library, which holds the Jonathan Williams papers, who assisted with the original Gilbert Russell Statement and other pertinent documentation, and to Melanie Bower from the Museum of the City of New York, which holds the Samuel Latham Mitchill papers. Mitchill, a Washington official, wrote daily to his wife, Catherine, describing Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and other historical figures.

Several Missouri institutions helped with strategic historical documentation, such as the Missouri State Archives, the Saint Louis Mercantile Library at the University of Missouri, the Civil Court Archives for the City of Saint Louis, the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Library, the State Historical Society of Missouri, and the Supreme Court Library of Missouri. There were also institutions that assisted from afar: the New York Historical Society, the Kentucky Historical Society, the University of Virginia's Small and Alderman Libraries, the New York Public Library, the Tennessee State Library and Archives, the Williamson County Court Archives, and two academic libraries in Saint Louis, Washington University's Olin Library and Saint Louis University's Pius Library. Special mention to Susan Snyder from the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, for her kind permission to republish the James MacKay archival map from the Louisiana Papers collection, and to Carolyn Doyle for granting permission to reprint the article from the Western Historical Quarterly.

My historical study evolved by drilling deep into a source that is so pervasive that it remains invisible most of the time: Google's digitization of out-of-print books. For the scholar, researcher, and student, this easy and quick aid is a formidable educational tool and one that I thanked every time I didn't have to go somewhere to read a book or obtain permission through interlibrary loan. This courtesy also applies to many smaller institutions like the Ohio History Online Portal, Cornell University Library: The Making of America, and the Wisconsin Historical Society, which publishes valuable online historical information.

These resources are only contributory when ably utilized, and much gratitude is owed to a tiny legion, a small “think tank” of individuals, who helped with the organization of a gargantuan amount of documentation. Robert J. Moore Jr., Lewis and Clark historian and author, grappled with numerous historical, textual, and technical aspects of the manuscript, and because of his guidance and editorial recommendations, the complexity of the project was less daunting. I wish to thank R. Mark Buller, a formidable researcher in the sciences, whose editing skills sharpened the focus of the subject matter, and Jeanne M. Serra, whose legal/medical expertise helped to hone my research when hunting for clues on Lewis's malarial condition and to build “brick by brick” dynamic presentations.1

I am also indebted to coauthors John Danisi and W. Raymond Wood for their expertise. John Danisi assisted with the final chapter, which required a logical, organizational structure to simplify the arguments surrounding Lewis's death.2 The chapter on Lewis and Clark's route map contained numerous details, and I thank W. Raymond Wood for helping me set the record straight, and for also agreeing to be a coauthor when I was an unknown historian at the time.3

There is also a ring of individuals who assisted with special services: Caesar A. Cirigliano, who gladly researched historical legal documentation from Tennessee;4 Professor Nancy Durbin of Lindenwood University, my eighteenth-century French translator; Bob Shay, who took a dull graph and redesigned it into a fascinating time line of Lewis's life, created the map of Lewis's “Final Journey,” and who also livened up most of the illustrations in the book; George Huxtable, for his remarks concerning on-land navigation; Lorna Hainesworth, for her timely contribution on the Cumberland Gap; Andrew Janicki, expert model maker of Fort Greenville, who provided much information on the Ohio forts; Patrick Riley, who provided information about persons connected with General Anthony Wayne and Fort Greenville; Jill Schriewer, for her statistical analysis on the Meriwether Lewis correspondence; Tony Turnbow, for sending the Williamson County Court minutes documentation; Zoe Lemcovitz and Catherine Lemcovitz, aka Mrs. Z., for their comments when reading early chapters; Jay Buckley for endorsing my research on Lewis's physical illness; Bill Gleason, for his encouragement when I first began to research history; and T. Melodious, Inc., for loaning out its chief audio designer to research and write early American history for the past thirty-five years!

Additional appreciation to the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, which supported my research on Meriwether Lewis with a grant in 2004; to Jim Merritt and Wendy Raney, the former editors of the foundation's scholarly journal, We Proceeded On, for publishing several of my articles; to Barb Kubik for her assistance with the foundation's grant and for other helpful suggestions. Special thanks to Lewis's descendants, Jane Sale Henley and Ann Sale Dahl and to Saint Louis chapter of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation members Jerry Garrett, Bev Leer, Patti Malvern-Frick, and LuAnn Hunter for their encouragement over the years.

I also laud the efforts of Prometheus Books, and specifically Steven L. Mitchell, editor-in-chief, for publishing American history. The staff at Prometheus has been both exemplary and highly accommodative with last minute details.

Lastly, and in retrospect, I have recently acknowledged a penchant for tracking down historical clues, which seems to come under the purview of one word: curiosity. It was ignited from an early age, and I thank my parents, Jack Francis Danisi and Mary Henrietta Kelly, for supplying the spark.

Ensign Meriwether Lewis of the 4th

SubLegion in arrest appeared for trial, and

challenged Capt. Marts, Lieutenants Bissell

Sterett and Webster from sitting as members

on his trial—

Ensign Rand, challenged on the part

of the United States—

Captain McRea, Lieutenants Diven

and Freemer, and Ensigns Richmond and

Scott returned vice those challenged

appeared—

Captain McRea, Lieut. Diven, Lieut.

Freemer, and Ensign Richmond challenged

by Ensign Lewis—

First page of Meriwether Lewis's courts-martial proceedings, held at Cantonment Greene Ville on November 6, 1795. (Anthony Wayne Papers, General Orders of Court-Martial, May 1793-October 1796, vol. 50, folio 49–91, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.)