The young United States was not a wealthy nation. Prior to the gold strikes in Georgia in the 1830s and California in 1848, little of material wealth had been found within the nation's boundaries. Relying almost solely on commercial import duties and tariffs for income, the nation had a handful of fledgling industries and no power to tax individual incomes or business profits. The nation also had a huge debt to repay, which it had incurred during the Revolutionary War. Due to the controversial fiscal proposals of Alexander Hamilton, the new federal government had assumed the debt of the Continental Congress and the individual states. It had borrowed money to pay off the international debt while settling on maintaining a perpetual internal or national debt and funding the government with secure bonds.

Of all the costs borne by the early treasury, it was the army, which had swelled in size to drive allied Indian tribes from the Ohio River Valley, that drained away the lion's share of the nation's paltry fiscal resources. Representative Albert Gallatin, a member of the House Committee of Ways and Means and later the secretary of the treasury under President Thomas Jefferson, believed that “military expenditures unnecessarily exhausted a nation's resources.”1 To that end, Gallatin sought the reformation of Treasury Department procedures and a severe reduction in the size of the military. Since the inception of the federal government in 1789, army or War Department officials had assessed the military budget, but Gallatin wanted a more rigorous process for overseeing and handling its administration.

Congress passed legislation in May 1792 creating the Office of the Accountant of the War Department, which made the War Department subordinate to the US Treasury Department in fiscal matters. This office “was authorized to settle all accounts and expenses of the War Department” and report from time to time “all such settlements for the inspection and revision of the accounting officers of the treasury.”2 This crafty congressional maneuver placed a unit of the Treasury within the War Department and effectively “tied the hands of the Secretary of War.”3 The accountant's office assigned to the War Department had complete autonomy and was housed in a separate building with six clerks. The first accountant, Joseph Howell (of which little is known), retired in less than three years. President George Washington appointed William Simmons of Philadelphia, then chief clerk, as the new accountant in April 1795.4

By an act of 1798, Congress separated the Navy from the Army Department, giving an accountant to each. Besides adding a messenger and another two clerks to the accountant of the War Department's office, Congress increased its duties to purchase arms and munitions and to oversee the finances of the Indian Department.5 From then on, the secretary of war's sole fiscal responsibility was to provide the department's budget, while the accountant's office strictly adhered to the settlement of incoming bills. The procedure for settling the accounts was simple; once the accountant finalized the vouchers for reimbursement, he made out a warrant for the settled amount, signed it, and sent it to the secretary of war for his countersignature. If the account could not be settled, the accountant sent a letter to the authorized officer discussing the discrepancy, and the exchange continued until an agreement was reached. If the account still met with resistance, legislation had been provided so that the accountant could send the disputed account to the comptroller for review. After 1802, the accountant stopped transferring the challenged expenditures to the comptroller, because it delayed payment for months, and decided to settle them himself.

The government accountants were the watchdogs of Gallatin's policy, and Simmons was scrupulous in his attention to detail as well as in familiarizing himself with all of the congressional acts relating to military law and procedure. The process by which an approved expenditure incurred by a military officer in the line of duty received reimbursement was arduous: it depended on the complexity of the account, sending the required documents to the accountant's office, waiting for settlement, and then receiving payment. The amount of time this bureaucratic exercise took could span up to three months, which was counterbalanced by local merchant conditions and the availability of specie money.

Various monetary instruments used in the regular course of business passed between the accountant and military officer-clerks, and terms such as warrants, vouchers, drafts, and bills of exchange were the subject of conversation. The accountant regularly employed warrants and vouchers. Warrants were authorizations signed by two parties validating that a transaction was legitimate, while vouchers were receipts showing the value of what was purchased. A draft was a sort of promissory note issued by an officer to a merchant for goods received, while a bill of exchange was a delayed transfer of money. Thus, a draft appeared to have ready value and was used much like a check today, but in Saint Louis, where specie money was scarce, the value was exchanged in goods. A bill of exchange only had ready value after it was sent to the government for reimbursement.

The scarcity of specie money was a serious problem and one that Lewis and Clark had to bear on their own through the use of drafts and a plethora of IOUs, which regularly circulated throughout Saint Louis. Clark wrote several times to the secretary of war explaining the dire necessity of having money available to pay for incidental expenses and was forced to authorize trips to Louisville to obtain it. Clark wrote to the War Department in 1808 that a “[g]reat demand for specie by the different offices of gov't. military agents & near the place is the cause of cash being very scarce and compels me to receive the money whenever I can get it and give bills—in several instances I have been obliged to send to the different towns near, for cash: and at two different times to Louisville; which is too great a risque, to bring silver (as a great portion of the country is yet a wilderness) and no bank notes to be procured.”6

Thus, officers who were appointed to positions that interfaced with the accountant's office were ill-equipped in the field, where stupendous amounts of paper or ledger transactions were necessary for consistent tabulation. If the figures were not correct, then the onus was placed on the officer's abilities when he sent bills in for payment. In the interim, the officer ran a deficit and sometimes used his own money to bridge the shortfall. What happened in many cases was that the accountant disagreed with the bill and returned it for review, and sometimes this happened repeatedly. But the cruelest part of the review process was invisible: if Simmons refused to settle the account, the disbursing officer was responsible for the difference, which came out of his own pocket.

In February 1799, Simmons infuriated a Capt. Samuel Vance, who had been trying to collect payment on a longstanding account. Vance, a veteran officer of six years, acted as paymaster, and a soldier in his regiment made a claim for clothing to the secretary of war. Simmons objected to the settlement and returned the papers without cause. When Vance met with him he asked Simmons to give him a reason why the claim was returned. Simmons believed the claim had been fabricated, what he called “a rascally one,” and that “the papers he now presented were insufficient.” This led to a heated confrontation between Vance and Simmons, during which Vance called Simmons a villain. Simmons felt “grossly insulted,” and took great exception to this treatment of an “executive in the duties of his office.”7 Simmons had Vance arrested and subjected him to a court-martial. While Vance was exonerated for any wrongdoing, Simmons's reputation was made as one to be feared.

Meriwether Lewis had met Simmons as early as 1797, when Lewis served as the army paymaster in Detroit, and a year later when he served on the recruiting service.8 While these duties placed Lewis directly in Simmons's purview, Lewis, a master of mathematical detail, had no problems with the accounting system during those years.

When the United States purchased Louisiana in 1803, the scope of the accountant's duties increased enormously because a myriad of jobs and official positions had to be created and appointed to administer the new lands. Forts would have to be built to protect the hundred thousand inhabitants, and territorial administrations would have to be created to govern and establish laws. Indian agents were hired to conduct business with the hundreds of Native American tribes on the west side of the Mississippi River, factories (official government trading posts) were established to facilitate the Indian trade, and a vast network of new opportunities was formed to serve a growing country.

The transfer of the governance of the Louisiana Purchase was divided into parts as a consequence of its size and the lack of infrastructure. Gen. James Wilkinson oversaw the American transfer of Lower Louisiana in New Orleans in 1803, and Capt. Amos Stoddard presided over the transfer of Upper Louisiana in Saint Louis in March 1804. Once the American government took control of Louisiana, the first task was to assess the existing military fortifications, and both Stoddard and Wilkinson reported that new forts were necessary. Forts required a multiplicity of supplies, materials, and purchases, which required authorized contractors to deliver a constant stream of goods on a regular schedule.

Stoddard's report recommended building a new fort eighteen miles from Saint Louis, to be named Fort Bellefontaine, and an important facet of that installation was hiring a trustworthy contractor to supply meat and other essential foodstuffs. The secretary of war hired T. & C. Bullitt in October 1804, months before the fort was built and when the troops were still using the old fortifications in Saint Louis as their encampment.9 The fort was completed in December 1805 and Bullitt, who had been delivering provisions in Saint Louis during construction, switched delivery to Fort Bellefontaine. Bullitt began sending bills for payment, but at some point Simmons refused to reimburse the contractor, and after repeated review over a number of years, Simmons began to ignore letters and bills from the contractor. By that time, the contractor had ceased doing business with the War Department but he continued to fight for reimbursement.

In November 1810, the comptroller of the treasury reviewed the case and could not understand Simmons's refusal to reimburse Bullitt. Simmons said that he would not pay because Fort Bellefontaine was not specified as the installation for which provisions were being procured in the original agreement. He was correct on that one point, but Simmons also argued that Henry Dearborn, the secretary of war, had fixed the price of incoming supplies. Gabriel Duvall, comptroller of the treasury and a lawyer, reminded Simmons that Dearborn had not consulted the contractor because he resided in another state and had made a decision “ex parte, and in justice ought to be considered as open to examination.”10 The comptroller immediately paid Bullitt.11

Simmons's rationale was not based on any legal footing but on faulty empirical reasoning. Importantly, there was no government entity or immediate superior who could force him to transfer contested accounts to the comptroller, even though legislation had provided for it. When Lewis returned from the expedition to the Pacific Ocean, Simmons required that Lewis present a formal accounting of the expedition expenses, but the intrinsic details of the expedition, namely the journals and notebooks kept by expedition members, paled in comparison to the extrinsic ones, which were the innumerable ledger items recorded by the clerks in Simmons's office.12

Lewis met with Simmons during the summer of 1807, but Lewis was too busy to track down incidental receipts when other important duties competed for his attention. Simmons wrote to Lewis when he was in Philadelphia that summer and said that he was going to suspend payment of Lewis's account until his arrival in Washington. “You will therefore do well to bring with you any papers or documents which may relate to your expenditures on the Expedition, so as to explain such of the charges as may require it.” Simmons said that the charges for subsistence to the men required the authority of the secretary of war.13 Simmons had no idea of the complexity of the business side of the expedition, nor did he care. He was simply trying to subtract money that the government owed Lewis.

When Lewis did not arrive by the appointed time, Simmons forced him to comply by dispatching another letter on July 31 raising the subsistence topic again; “I conceive it would be proper, before I finally close the account to be laid before the Secy. of War for the approbation of the President of the United States.”14 When they finally met on August 5, Lewis had difficulty producing paper for every transaction, and unbeknownst to him, Simmons back-charged those amounts, reporting that Lewis owed the government $9,685.77! Even though President Thomas Jefferson provided Lewis with a carte blanche letter of credit for expedition expenses in 1803, Simmons reported this egregious amount, which was printed in a Treasury publication for debtors. Lewis was expected to pay the overage within three years or a suit would be filed by the government.15

Once Lewis completed his business with Simmons he departed Washington, en route first to the Burr trial in Richmond, Virginia, and then to Charlottesville to pack and head toward Saint Louis. Lewis met with Gen. Wilkinson in Richmond at the trial and probably talked with Wilkinson about the continual squabbles with the accountant. He likely found a sympathetic ear with Wilkinson, who had been ordered by the War Department to attend the Burr trial and to provide testimony, yet Simmons refused to pay the bill for his expenses to do so. Wilkinson explained in a letter to Secretary Gallatin that “the conflict is not between Burr, the conspirator and the United States, but between an injured citizen and a despotic vindictive executive & a military panderer. I am sick of it.…” He had spent $160 traveling from New Orleans to Richmond, Virginia, and was “almost penniless.”16

Two other incidents exemplify Simmons's autocratic reign. For years, Simmons had been fighting with Gen. Wilkinson, and he finally had enough documentation to convene a court-martial hearing in 1808 by claiming that Wilkinson had irresponsibly spent thousands of dollars in a four-year period. The general had allegedly hid the expenses in extra rations and quarters and in forage for horses. Simmons sent the complaint to Henry Dearborn, the secretary of war, who then informed President Jefferson and Caesar Rodney, the attorney general of the United States. Rodney pointed out not only that Wilkinson was a brigadier general, but also that, as the nation's overall military commander, he was entitled to additional awards from the president, and thus, Wilkinson, because of his rank, was permitted to enjoy those benefits.17

Simmons disagreed, which prompted Dearborn to send a complaint to the comptroller. What is evident from this exchange is that the secretary of war was, surprisingly, subordinate to the Treasury Department in this matter. Also by virtue of the fact that Dearborn had to explain his position, it is evident that the Treasury Department made the ultimate decision.

Having understood that the accountant of this department has doubted the legality of an allowance I had, with the approbation of the President of the United States, directed to be made to Gen. Wilkinson…commanding officer at New Orleans…I take the liberty of stating the facts.…In the 5th section of the act fixing the military peace establishment, passed March 16, 1802, the President is authorized to allow the commanding officers of posts…additional number of rations, as he shall deem proper…. In the compensation Gen. Wilkinson receives by law, as brigadier-general, the usual rations were estimated; but it is presumed that this cannot justly bar him from an extra allowance…which, in the opinion of the United States, would entitle any other officer to an extra allowance of rations. This allowance to him for quarters…is nothing more than what is granted to all other officers according to their respective grades, although there has never been any law for furnishing officers or soldiers with quarters, any more than for tents or fuel…. I…have thought it my duty to make this statement to you, to aid in any opinion you may please to give.18

The comptroller agreed with Dearborn and passed on a credit to Wilkinson.19 This unanimous decision angered Simmons, and, incredibly, he turned over Wilkinson's account to a Washington newspaper, going public with the information that government officials had approved $56,000 of public money for frivolous expenditures. Simmons's tirade stated, in part:

Fellow-citizens…your treasury has been plundered…by the connivance of the President, the Secretary of War, and the Attorney-General of the United States…. [W]ith such facts staring them in the face…the democratic members of the legislature…have offered the most…unqualified approbation…of the administration thus…sanctioning, countenancing, and encouraging the most gross and abominable fraud and peculation.20

Simmons was in a unique position of power, as evidenced by the fact that he did not incur any penalties or censure for this violation of government privilege and releasing internal, nonpublic documents to the press.

Simmons hounded individuals like Wilkinson, whom he believed stole money from the government. He also attacked Gilbert C. Russell's tenure in the army from 1803 to 1810. Capt. Russell, commander of Fort Pickering, is a well-known figure in the literature because he cared for the ailing Lewis in the final two weeks of September 1809 and had wanted to accompany him to Washington but did not receive his orders in time. Russell was from Tennessee and was a friend of Sen. Joseph Anderson, also from the same state. On two occasions, Russell circumvented Simmons by giving his protested accounts to Anderson, who pushed them through channels and ensured that they were paid in April 1806.21 When a few months later Simmons wanted Russell arrested for defrauding the government, Russell explained the circumstances: “The accountant pretends or wishes to attach criminality to me for receiving pay for the months of October and November 1806 after passing receipts to William P. Anderson of Nashville T.”22 Russell asked Dearborn to make a formal inquiry, and, if his action made an “unfavourable impression,” he wanted the secretary of war to make things right, even if it meant his discharge.23

Simmons was the ultimate fiscal predator when judging what he thought were erroneous expenses, but according to congressional law, he had no authority to judge any account. Legislation provided the accountant's office with the means to send disputed accounts to the comptroller for review, and he would then render a decision. Over the course of Jefferson's administration, the comptroller reminded Simmons several times of that specific rule:

As the accounting officers of the treasury are authorized to revise settlements made in your office, and not to decide on claims in the first instance, it is necessary that you should admit or disallow the claim, in order that it may be finally decided on in this department.24

No matter, every disbursing agent became Simmons's prey regardless of what the comptroller had reminded him. His zeal to force military officers to conform not only to the fiscal laws, but to his sometimes bizarre interpretations of the laws, worsened after the passage of the Embargo Act in 1807, which was an attempt to financially strangle England by ceasing to export or import furs and other goods.25 The United States suffered greatly under the embargo because England was the nation's chief trading partner during the era. As a result, Treasury Secretary Gallatin tightened budget expenditures and imposed stricter regulations for military and territorial reimbursements. This budget tightening affected Upper Louisiana, a distant territory awakening from fiscal dormancy

The beginning of Lewis's financial troubles began with the return of the Mandan chief, Sheheke-shote, to his village along the Missouri River in modern-day North Dakota in May 1807, which was about a year before Lewis arrived in the territory. While Lewis was in Philadelphia working on the journals for publication, William Clark had been sent to Saint Louis in the spring of 1807, and his first order of business was the return of the Mandan chief and his family The genesis of the problem stemmed from the invitation of Lewis and Clark to the chief and his family to accompany them to Washington to meet with the president. The chief returned to Saint Louis in March 1807 to await transport home. Dearborn approved a military escort to accompany the chief, but due to the insufficient number of troops stationed at Fort Bellefontaine, he instructed Clark to use a combination of military and civilian personnel to take the Mandan entourage up the Missouri River.

You are authorized to draw on this Department, for four hundred dollars, to be laid out in suitable articles to be sent with the party, as presents to the Mandan Nations…you will likewise draw on this Department such Sum as may be found indispensibly necessary in fitting out the party for the Voyage…. Should any merchants or traders be found disposed to send goods as high up the Missouri as the Mandan towns, and will, without delay take measures for dispatching a suitable number of men with such goods so that they may be associated with the voyage…you will afford them encouragement, by granting them licenses to trade with the Indians generally on the Missouri from the Ricaras upward: and engage…for two years at least, no other persons will be licensed to trade with those Indians.26

Dearborn also allowed Clark to “furnish, each man…ammunition for the voyage…at the expense of the United States,” and also instructed him to recruit as many suitable men to enlist in the army for five years.27 There were no takers.

One of the Louisiana territorial judges, John B. C. Lucas, wrote to a friend explaining that various trading companies were feuding for the Mandan contract.

There is a company forming here for the purpose of carrying on the fur trade on the heads of the Missouri, it is all ready composed of eight or nine parties; the funds of the Company amount…to…$5000, there were at first two or three companies…who were all…jealous of each other; and whose interest…might have led them to mutual injury, after various conferences they have…agreed to consolidate their interest into one, it is said that the expedition will take place in the course of next month, the whole party will come to one hundred men, several of the partners are going with the expedition, they will not return for three years.28

Clark, adept at discerning tense Indian relations, thought that the party escorting the Mandan chief would encounter hostility somewhere up the Missouri. He believed that the strength of the escort required manpower and cobbled together an impressive number of persons from various groups: a Sioux deputation, two trading ventures, and two military escorts. The Sioux deputation was going to the Yankton Indian village in modern-day South Dakota, while the Mandans would press on to North Dakota. The group totaled 101 adults composed of soldiers, traders, boatmen, interpreters, hunters, Sioux warriors, and from the Mandan nation, eighteen chiefs, men, women, and six children.29

The group departed Saint Louis on May 18, 1807, and split up on August 23 when the main party journeyed onward to Mandan territory.30 The party was attacked on September 9 by hundreds of maddened Arikara Indians, and four men were killed, five wounded, and the rest narrowly escaped to Saint Louis.31 George Shannon and Renè Jesseaume were two of the men wounded in the melee; they had accompanied Lewis and Clark, Jesseaume during portions of their 1804 to 1806 journey, and Shannon for the entire trek. On this trip they were not so lucky; Shannon had his leg amputated in Saint Louis and Jesseaume “received two dangerous wounds that made one fear for his life, and which retained him more than four months in Saint Louis, without being able to get out of bed.”32 The cost of the stricken military escort totaled about $6,500.33

Pierre Dorion, the Sioux interpreter who accompanied the Mandan party, survived the ambush. Dorion visited Saint Louis in May 1807 with a Sioux delegation and entreated Clark to pay him his salary, which had not been accomplished since his appointment as interpreter in December 1805.34 Clark was reluctant to pay him because there was a chance that he would quit, and Dorion's role was too important to be vacated. Remarkably, Clark instead gave gifts to the Sioux and urged Dorion to send yet another letter to Simmons.

I take the liberty of representing to you…that my Salary as Sub-agent is barely Sufficient to the maintenance of my family and that the expences I have been compelled to incur to obey the orders of government or rather of persons employed by them cannot be charged to me: I have been obliged to borrow, to meet these expenses, and I am now at the mercy of my creditors: I must then entreat you to give the most prompt orders to reimburse me for the two due…amounting to $1061.96 and which have been entirely employed for the service of the Government…in my last journey, I ran a risk of loosing my life, having been struck by the Ricara [Arikara] Savages.35

Simmons ignored Dorion's plea.36

When Lewis arrived in Saint Louis in March 1808, the Louisiana territorial administration had been in neglect for almost three years, a sure sign that large sums of money would be required to fix it. Even Frederick Bates, the most boastful and egotistical official in Saint Louis, and Lewis's territorial secretary, believed that his best judgments for the discharge of the duties of government were so difficult that “I feel that I am no atlas for so great a weight.”37 After only one year on the job, he believed the territory had been an insupportable burden and was relieved that his tenure had ended as acting governor. “It was a task to which I thought myself unequal even before experience had demonstrated the truth of my fears.”38

This was a really bad omen because Bates, who had been a capable Detroit administrator, had concluded that territorial problems abounded in every sector of Upper Louisiana. The new governor, Meriwether Lewis, would be forced to confront a daunting diversity of territorial issues, which would take varying amounts of money and latitude, and put him in economic peril. The Jefferson administration was oblivious to the most obvious: their star pupil was on a collision course with Simmons's office. Issues that required Lewis's immediate attention centered on language barriers, warring native Americans, trading licenses, bootlegging, property rights, mineral lands, squatters, civil unrest, amending and printing territorial laws, forming a militia, protection and safety, enactment of laws, murders, theft, and hiring Indian Department personnel. The most vexing problem centered on the return of the Mandan chief and his family to their homeland.

Upon Lewis's arrival in Saint Louis, he paid his men from the rewards of the expedition. Lewis had received a load of credit, which amounted to double pay for expedition members and a generous grant of land for each in the Louisiana Territory. Lewis set about paying some members of the expedition who remained in Saint Louis after their return in September 1806. William Clark, who had been appointed Indian agent for the Louisiana Territory, was due to arrive in Saint Louis with his new bride in June, but pressing matters surrounding Indian Department business forced Lewis to immediately take action, and he paid the Sioux interpreter, Dorion.39

A priority vying for reform was the enactment of territorial laws, which would quell civil unrest and murders. The unrest had occurred mainly in Sainte Genevieve, a town ninety miles south of Saint Louis, due to the abundance of lead in the hills to the west, which prompted a landgrab and resulted in the so-called mineral wars. Indian murders had garnered special attention due to selling liquor to Native Americans, which was forbidden but, nonetheless, took place, prompting more hostilities. Beginning in June 1808, Lewis convened the territorial judges and soon began passing a wide range of laws.40 Once Clark arrived in Saint Louis the division of responsibility between the two fell into the same pattern as when they had commanded the expedition. The administration of the territory began to take shape with military precision.

One challenge that the two could tackle together revolved around safety for the territorial residents. The Upper Louisiana country had always been an unsafe locale due to the large number of tribes in the area and a severe shortage of troops, first with the Spanish administration and then with the Americans. Normally a territory's second line of defense fell to the militia, except in Louisiana few were eager to volunteer. Indian hostilities had been on the rise owing to the ever-expanding American frontier and discontent about American settlements. Saint Louis was a relatively defenseless place, and the subject of one Indian raid. Lewis and Clark's answer to the problem was to galvanize the residents into accepting their militia duties. The perception of an organized militia would have “a powerful effect” upon the Indians, which Clark had hoped would “prevent the intended Blow altogether.”41

In spite of all these demands swirling about him, Lewis took time off to see Saint Louis and began buying prime real estate in the Saint Louis area. Territorial governors were required by law to own a freehold estate of a thousand acres, and Lewis knew a good deal when he saw it.42 By the end of July 1808 he had purchased about 5,700 acres for $5,530. One of the tracts had a good source of flowing water and would make “an excellent mill seat.”43 The purchase terms were generous, and Lewis could pay the balance over the next year.

Lewis invited Joseph Charless, a printer from Louisville, to establish a newspaper in Saint Louis. A printer was vital to the territory for publishing national events, advertisements, and the local news, not to mention the compendium of Lewis's new territorial laws. Lewis sent Charless $225 in bank bills and a draft as a loan to establish the printing shop, but Lewis learned that the post rider had drowned in the Little Wabash River and the funds had disappeared. He then raised the exact amount again and sent it to Charless.44 Another item lost in the rider's pouch was Dorion's payment, which did not become apparent for some time, and when Lewis sent a duplicate bill, he was not reimbursed. This was yet another example of Lewis's lost income, which would diminish his personal wealth and negatively affect him the following summer.45

Lewis hired a favorite interpreter, Peter Provenchere, to translate the territorial laws into French, which would then be published and circulated throughout the territory.46 Provenchere had accompanied the Mandan entourage to Washington. He spoke and wrote several languages, and coupled with Charless's talent, the two could commence proper communications in the town.

In July 1808, Lewis advanced Charless $500 for the purchase of paper for publishing the territorial laws, 250 copies in English and 100 in French.47 At the end of the month, Lewis gave Provenchere a partial payment of about $71, and sent the bill to James Madison, the secretary of state. At the end of 1808, he paid Charless the balance so that the publication would be ready in the first quarter of 1809. In all, Lewis disbursed about $1,500 of his own money, and after sending invoices for each expenditure with the reasoning behind them, all of them were rejected by the secretary of state's office! This was puzzling because the secretary of state was required by an act of Congress to reimburse governors when they published public laws.48

Earlier in the year, Dearborn ordered Lewis to hire several persons to explore the saltpeter caves on the Osage River. He wanted a detailed report on its extent, quality, distance from Saint Louis, and how long it could be worked. Saltpeter was a major component of gunpowder, and the secretary was looking for extensive deposits of the mineral that could be worked for at least seven years. In mid-August Lewis hired two persons to carry out the work, but when he sent the $730 draft for reimbursement, Simmons refused to pay it.49 This refusal did not make any sense unless Simmons was trying to delay what he believed were unauthorized expenditures.50 From a strategic point of view, it delayed planning for the defense of the territory.

A new fort and trading factory was to be established about 250 miles up the Missouri River, and the trading facility at Fort Bellefontaine would close in November 1808. About eighty soldiers accompanied William Clark, who would select the site, and the fort would be built beginning in September 1808.51 Clark, as the new Indian agent of the territory, would officiate at a treaty signing, exchanging American goods for Osage Indian land and offering protection using the fort's resources. What Clark had in mind, however, was seen as being disadvantageous to the Osage, and Pierre Chouteau came to their rescue by interfering with the treaty signing.52

A few days before Clark departed Saint Louis, he wrote to Dearborn inquiring about the timing for the second attempt to return the Mandan chief to North Dakota. It would take time to prepare and obtain approval for those plans, and Clark had set his sights on the spring of 1809, since “Govr. Lewis will be absent at that time,” editing the journals for publication.

If the Government does not intend to send a Military Command with the Mandan Chief next Spring, and you think it necessary that arrangements should be made in this country…to send him up to his nation…if I am to make the arrangements…to get him to his Country I must request the favour of you to inform me. That timely preparations may be made by some party so as to let out early in the spring—My former plan has been defeated for the want of a few more regular troops, or a sufficient time for a large company to equip themselves. I think a Company can be formed of Hunters & Traders attached to a few troops who will take up the Indians, if Government should not send a large command into that country.53

Clark's letter did not reach Dearborn until September 23, and it took until mid-November before he received the secretary's approval.54 By late October, Lewis and Clark learned that the Osage Treaty signed at the new fort was refused due to Chouteau's interference, which forced Governor Lewis to revise it and invite the Osage to Saint Louis.55 This took much preparation and there were two signings, one with the Big and Little Osage on November 10, 1808, accompanied with multiple Indian councils, and the other on August 31, 1809, during which the Arkansas Osage delivered up “200 miles square of the finest country in Louisiana for which they received merchandize to the amount of about $2500.” Clark recommended that the Senate ratify the treaty as it would “require five times the amount to effect a purchase of the same tract.”56

In December, officials in Saint Louis commented that Lewis was about to leave the territory and travel to Philadelphia to work on the publication of the journals. Every time that Clark, Bates, or Lewis mentioned his imminent departure, Lewis was forced to stay and work out another problem in the territory. The time of departure was finally fixed and Lewis wrote his mother that “you may expect me in the course of this winter.”57 Lewis and Clark were relying upon Territorial Secretary Bates to assist Clark, but the plan backfired when he flatly refused. “Mr. Bates has very earnestly requested of me not to impose on him duties in the Indian department during my absence, alleging that it is a subject with which he is wholly unacquainted.” Pierre Chouteau's interference with the signing of the Osage Treaty had caused tension between Clark and Chouteau back in September. Lewis wanted Bates to act as a buffer between them, but Bates was not interested. “Mr. Bates is extremely unwilling to exercise the authority of superintendent,” Lewis wrote.58

While the issues with Bates had finally come to a head, two other events prevented Lewis's departure. The first was the establishment of the first Masonic lodge in Saint Louis, which occurred on November 8, 1808.59 The second event was unexpected; from mid-November to almost mid-January, Lewis had again succumbed to a malarial relapse.60 During the times that he was not ill, he composed a long letter to Thomas Jefferson detailing the Osage Indian Treaty. 61 A shortened version was printed in the American State Papers, but historians have yet to acknowledge that Lewis was still communicating with the president.62

The letter was long and divided into multiple sections, which amounted to fifty pages.63 Once Lewis regained his strength, the weather turned bitterly cold and Lewis and Clark began to organize the mission to return the Mandan chief, Sheheke-shote, to his nation. It took almost the entire winter to assemble the parties to be engaged in the enterprise, sign papers, and to set deadlines.

In his quarterly briefing to Congress in December 1808, Treasury Secretary Gallatin reported that the Embargo Act had strangled the life out of the nation's economy and that government revenue had dropped by $6 million from the previous year and was “daily decreasing.”64 For all intents and purposes, the US government was broke, and he recommended that President Jefferson rescind the Embargo Act.65 In a frantic effort to economize, Gallatin believed that the War and Navy Departments still had excesses to wring from their budgets:

It is believed that the present system of accountability of the military and naval establishments may be rendered more prompt and direct, and is susceptible of improvements which, without embarrassing the public service, will have a tendency more effectually to check any abuses of subordinate agents.66

The term “subordinate agents” was a broad stroke that included a wide range of government appointees, contractors, and hirelings who had been qualified and vetted by high-ranking American officials. Gallatin's newly found religion of economy served to further embolden a man like Simmons, and it was bad news indeed for military officers and other government officials who expended their own money and were then subject to intense scrutiny over every penny spent.

The election of James Madison to the presidency in 1809 contrasted the politics of two administrations, one departing and the other arriving.67 Jefferson's model of expansion would soon give way to Madison's model of contraction, but a few days prior to Madison's inauguration, Secretary of War Dearborn stepped out of character and suddenly recommended the removal of William Simmons:

It was early perceived that the passions, prejudice, general disposition and character of the Accountant of the Department of War, rendered him very unsuitable for the Office he holds; and I should have applied for his removal several years ago, had I not been induced to expect, from year to year, that such an arrangement would have been made in relation to the Accounting Offices of the War and Navy Departments, as would have superseded the necessity of such an application. But of late the conduct of Mr. Simmons has been such in regard to the Head of the War Department as to compel me in justice to that Department and to the Office I have had the honor of holding, as well as to my Successor, to request that he be removed; and I am fully pursuaded that the opinion of the public Officers generally who have been acquainted with his character and conduct accords with mine,—that he ought not to be continued in Office.68

For all those unfortunate officers over the preceding thirteen years who had wrestled with receiving reimbursement for expenses honestly incurred in the performance of their duties and for the benefit of the United States, Dearborn's letter finally condemned Simmons's behavior and his “perplexing incapacity in the settlement of public accounts.”69 Unfortunately, the letter was an empty threat; if he had only attached proof, including specific charges, outgoing President Jefferson could have removed Simmons. Why, then, did Dearborn write the letter? Perhaps in response to his own guilt of inaction and to alert his successor of the accountant's conduct.

Madison's appointment to replace Dearborn as head of the War Department was William Eustis, a trained physician who had served four years in the House of Representatives from his home state of Massachusetts, and then as a hospital administrator. It is baffling why Madison appointed Eustis to one of the most demanding posts in the presidential cabinet, which was reiterated by Treasury Secretary Gallatin when he wrote of Eustis's “incapacity and…total want of confidence” throughout the public service.70 Eustis had little military experience per se, although he had been a key surgeon and hospital administrator during the Revolutionary War. The appointment may have been purely political; Eustis was a staunch Republican in the midst of Federalist New England and had won his races for his House seat in opposition to John Quincy Adams and Josiah Quincy III, narrowly defeating both. Eustis began his official duties on April 5, 1809, but had little effect on the department's accounts payable, not being directly involved in the process. Simmons communicated with all disbursement officers when settling their accounts—not Eustis. And even if Eustis had the authority, he knew nothing about War Department business, being completely unfamiliar with its personnel for the first six months of his tenure, which spanned the final months of Lewis's governorship of the Louisiana Territory.71

In the fall of 1808, Saint Louis officials had been working out the details for the coming year. At the top of the list was the inadequacy of the mail system where the Louisiana Territory was a distant point on the rider's trail, resulting in the slow delivery of important correspondence and reimbursements.72 Lewis made a formal complaint to the postmaster general detailing those delays and why improved delivery was absolutely critical to the efficient administration of the territory. Gideon Granger, the postmaster general, admitted that he had been “apprised of several failures,” but wintertime was notorious for “deep snow and uncommon high water,” which further hampered delivery.73 While Granger said that he would launch a “strict investigation,” it would take much time to complete.74

The slow delivery of the mail was but a minor distraction compared with one of the thorniest problems still facing Governor Lewis. In February 1809, Lewis and Clark devised a new and bolder plan for returning the Mandan chief to his village. No one wanted a repeat performance of the dead and wounded men that had resulted from the 1807 attempt on the books of the territorial administration. Further delays in returning the chief and his family would only make the United States look weak in the face of tribal power, leading the Mandans to consider the US a poor trading partner and military ally. On a personal level, neither Lewis nor Clark needed reminders of George Shannon's amputated leg or the complaints of Renè Jesseaume, the Mandan interpreter, of his shoulder and thigh wounds, even though both men received a salary while they recovered.75 In hindsight, placing the entire responsibility for the success of the 1807 expedition on Ensign Pryor had been a mistake, and Lewis realized that experienced personnel were essential.

Borrowing an idea from Secretary Dearborn's instructions of March 1807, the Missouri Fur Company (MFC) was formed to take advantage of a once-in-a-lifetime endeavor, funded by the US government. The project set up a fur trade company with the intention of “killing two birds with one stone.” The lucrative business aspects of the proposal would draw investors and participants, while the large party of men assembled would be able to successfully fight its way past the Arikara blockade of the Missouri River—if that became necessary. The fur trade aspects of the proposal were enticing because the scheme was designed to propel the company's hunt of beaver beyond hostile territory into the relatively peaceful region of the Upper Missouri.

The MFC sold shares in the company, and William Clark became one of the partners along with other wealthy Saint Louis and Cahokia residents. Lewis felt that Pierre Chouteau, the Osage Indian agent, was the fittest person to lead the expedition, and his experience in the fur trade and with native peoples was equal to the task. At the end of February, plans for the Mandan expedition were laid out and the contract was signed. Lewis wrote six drafts on March 7, 1809, amounting to $7,000, and he explained what the money would buy:

[T]he said company are likewise bound to raise or organize arm and equip at their own expense One hundred and forty effective volunteers to act under my orders as a body of the militia of this Territory, and to furnish what ever may be deem'd necessary for the expedition, or to insure its success.76

In the meantime, Clark wrote to the War Department asking to build an Indian house and storage facility for peltries in the town of Saint Louis, near where Lewis and Clark engaged in daily business matters.77 At the time, the Indian house was located at Fort Bellefontaine, eighteen land miles north of Saint Louis, which was too far for Clark to manage, but the rates for renting in town were exorbitant. Clark knew that he could save the government a large expense if they constructed and owned buildings for this purpose near the governor's office.78

Clark's letter dated January 26, 1809, was addressed to Dearborn, but when it arrived in Washington, Dearborn had resigned and the letter was given to Simmons, who proceeded to dismiss Clark's proposal and criticize him for past expenses:

Before any authority can be given for erecting the buildings proposed in your letter…it is necessary that this Department should be furnished with a partial estimate of the expense—The Expenditures in the Terr. of Louisiana on account of the Indian Department have exceeded expectations; the amount in 1808, was not less than $20000—you will please therefore in future…forward to the Secy. of War quarterly estimates of the Expense in your Agency—They should be transmitted in sufficient season to enable him to advise you of his Approbation, before any Bills are drawn on that department.79

An important piece of information in Simmons's reply was a new government mandate of quarterly estimates, which contained instructions that Lewis and Clark could not have anticipated and would be problematic due to the inadequate mail system. Clark sent his letter on January 26, and received, on July 1, Simmons's May 11—dated reply. That one communication cycle took five months to complete. The whole idea of quarterly estimates, coupled with the inadequate communication system and lag times, made reimbursement for territorial and Indian Department expenses a long and cumbersome process. Added to this was the wild unpredictability of Simmons and the ever-present possibility that legitimate expenses incurred out of the pockets of government officials would not be reimbursed on some technicality. Although Simmons said that expenditures required the secretary of war's approbation, that was not true either in law or in practice, because the mandate gave Simmons extraordinary power and he became both judge and jury on all War Department disbursements.

As territorial business increased over the next couple of months, an unforeseen event further disrupted Governor Lewis's financial affairs. A federal official in Saint Louis criticized the plan to return the Mandan chief and wrote a formal complaint to his superior, John Mason, superintendent of Indian affairs. Rodolphe Tillier, the factor of the Indian factory at Fort Bellefontaine, gave damaging information in his complaint that enabled Simmons to further disable Lewis's administration.

There is no doubt that Tillier had an ax to grind. When Clark established Fort Osage in August and September 1808, the trading factory at Fort Bellefontaine was relocated, and Tillier's position was terminated. He believed that Lewis had recommended his removal because of an altercation that had resulted in the firing of his assistant, George Sibley, in November 1807.80 In reality, the factory was moved because Gen. Wilkinson suggested its relocation as early as 1805 to a location close to where the tribe actually resided, and Dearborn had approved the move.81

Tillier waited for the change in the presidential administration to inform Mason of his version of Lewis's plan and sent three letters.82 Tillier supplied trumped-up and inflammatory information to Mason in an attempt to land a new job:

To represent the present situation of these remote parts of the United States Territory may be of public service, to the wise administration of your Excellency; and can give no offence if founded on Fact & real Truth.

Two years ago an Expidition had been made here under the command of Lieut. Pryor to take back the Mandan Chief & family, it failed on account of being coupled with a private expidition…as no inquiries have been made of the real cause, tho’ the Public has suffered no fault…that it was entirely owing to the Misunderstanding and Mismanagement of the parties of Lieut. Pryor and Chouteau's people.

Last year a War was predetermined against the Osages & all the surrounding savages were invited in grand Council to join the Administration utterly to destroy them, without ever manifesting any plausible ground or reason.…I am well informed by one of the principal Osage interpreters that if they did not submit they were threatened to be utterly destroyed from the face of the Earth!

There is an other expedition on foot of about 200 men divided into shares to hunt Beaver in the upper part of the Missouri…however it was after designed…to bring the Mandan Chief and family home that the Governor promised the company seven thousand dollars if delivered safe. at present it seems by Proclamation of the Governor to be altogether on public account, man'd & officered and paid as U.S. militia.…Is it proper for the public service that the U.S. officers as a Governor or a Super Intendant of Indian Affairs & U.S. Factor at St. Louis should take any share in Mercantile and Private concerns.83

Tillier was not privy to any discussions between Lewis and Clark, and what he reported to the War Department was a distortion of the facts.

Two weeks later, Tillier sent another letter deploring Lewis's plan, which was “afeared not a creditable one.”84 In his final letter, Tillier baited Mason to forward his version of the events to President Madison.

I intended to send the enclosed to his Excellency the Pres. After mature deliberation I have changed my mind, & submit to your judgment if the Facts alledged may be interesting to him, or the U. States or if it will be better to bury them in oblivion in either case, disclaim any personal motive of ill will, or interested motive of courting favour at the expence of another.85

Mason dutifully forwarded the letter to Madison, which set off a chain reaction of events that ended with the president's approval to reject any other payments above the initial cost of the expedition, empowering Simmons to execute the order.86

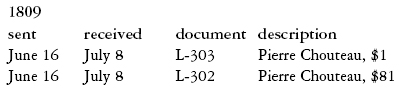

Lewis's original drafts of $7,000 were paid, but in May he sent three other bills connected to the expedition without including a quarterly estimate. Those three drafts did not arrive in Washington until October 7 and would not be paid in time, which meant that Lewis's liquid capital was greatly reduced. The following is an itemized list of Lewis's transactions pertaining to the cost of the expedition:

By this time Lewis had received two refusals for inconsequential sums from the secretary of state and had already returned them to the secretary of the treasury.88 Not having heard from the War Department, he sent two additional bills on June 16. Those two bills arrived three months before the ones sent in May, which arrived on October 7, 1809.89

Clark replied to Simmons on July 1 acknowledging that he would begin submitting quarterly estimates and sent a detailed bill with a list of Indian agents, subagents, and interpreters “who received their salary from me…authorized by the Secty. of War or the Superintendent of this Territory.”90 When Simmons received Clark's letter, he rejected eight of the twenty-two salaries, which amounted to $1,069.91.91 That meant that Clark had to pay those men from his own funds until he either had the time to meet with Simmons face to face or appeal the rejection of his request. Simmons explained his position on the matter:

Those appointments have not been authorized or approved by this Department; nor has the expediency or propriety of making them been submitted to the Government; or an opportunity given to determine, whether the appropriations for the Indian Department would justify such an increase in expenditure. It does not appear to be necessary that the expense attending our Relations with the Indians in the Territory of Louisiana, should be four times as much as the whole expense of supporting its civil government.92

It must have been infuriating for Lewis and Clark to be reprimanded by a person who knew nothing about Louisiana territorial affairs and who ignored previous authorizations from Dearborn. After receiving a rejected payment from the Treasury Department for a miniscule $18, Lewis waded into the financial depths and wrote to Simmons on July 8 hoping for leniency. This letter, which has never before been published, shows that Lewis was extremely worried over all of his unreimbursed expenditures up to that time:

[T]his occurrence has given me infinite concern as the fate of other bills drawn for similar purposes to a considerable amount cannot be mistaken; this rejection cannot fail to impress the public mind unfavourably with rispect to me, nor is this consideration more painfull than the censure which must arise in the mind of the executive from my having drawn for public monies without authority; a third and not less imbarassing circumstance attending the transaction is that my private funds are entirely incompetent to meet those bills if protested….93

By this time, Mason had received the three letters from Tillier regarding the alleged improper federal funding of the fur trade expedition to return the Mandan chief, and he forwarded them to President Madison. Coincidentally, on July 8, Simmons had just received an odd letter from Pierre Chouteau. The Osage Indian agent always corresponded in French, but this letter was written in English; it had in fact been penned by Territorial Secretary Frederick Bates and Chouteau had signed it. The letter was undoubtedly meant to derail Lewis's administration as governor of Louisiana:

The contract…transmitted by the Governor, will have given…the principles of this arrangement…it is as well mercantile as military…a detachment of the militia of Louisiana as high as the Mandan-village and commercial afterwards…. If my participation in speculations of this kind should excite the surprise of government as inconsistent with my duties…I…refer you to Governor Lewis, whose advices I have pursued…. My agency has…been limited to the Osages, and…I accompany the expedition, merely in a military capacity…and as soon as my command ceases at the Mandan Village, shall return with all convenient haste to Saint Louis.…I take the liberty to enclose a Power of Attorney, by which my son Peter Chouteau…is empowered to draw in my absence….94

Bates had almost certainly concocted the contents of this letter, and the insinuating tone is typical of his writing style. His hatred for Lewis by this point in time was palpable and was a clear motivation for the veiled hints of impropriety: “If my participation in speculations of this kind should excite the surprise of government as inconsistent with my duties…” The other part allowed Simmons to judge the legality of Chouteau's temporary lateral move: “I take the liberty to enclose a Power of Attorney…”

Instead of merely weighing the ethics of the proposed expedition in light of the insinuations of the letter, Simmons used the power of his office as well. True to character, Simmons decided that Chouteau had vacated his position as Osage Indian agent in order to lead the expedition and so terminated his salary. Simmons then wrote a nasty letter to Governor Lewis, on July 15, that had President Madison's sanction:

After the sum of seven thousand dollars had been advanced on the Bills drawn by your Excellency on account of your Contract with the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company…and after this Department had been advised that “for this purpose the Company was bound to raise, organize, arm & equip at their own expence one hundred and forty Volunteers and to furnish whatever might be deemed necessary for the Expedition, or to insure its success”—it was not expected that any further advances or any further agency would be required on the part of the United States. Seven thousand dollars was considered as competent to effect the object. Your Excellency will not be surprized that your Bill of the 13th of May [to pay Pierre Chouteau $500]…has not been honored…. 95

Since Simmons had not received a quarterly estimate from Lewis, he rejected the payment out of hand.

Although Lewis hadn't really explained the details of the expedition to Simmons, Tillier and Bates had given the accountant ample misinformation, which Simmons used against Governor Lewis:

In…accepting the volunteer services of 140 men for a military expedition to a point and purpose not designated, which expedition is stated to combine commercial as well as military objects, and when an Agent of the Government appointed for other purposes [Chouteau] is selected for the command, it is thought the Government might, without injury to the public interests, have been consulted. As the object & destination of this Force is unknown, and more especially as it combines Commercial purposes, so it cannot be considered as having the sanction of the Government of the United States, or that they are responsible for the consequences…Being responsible for the expenditure of Public money & made judges in such cases whether the Funds appropriated by the Legislature are applicable and adequate to the object, it is desirable in all practicable cases that they should be advised and consulted when expenditure is required. As the Agency of Mr. Chouteau is become vacant by his accepting the command of the Detachment it is in contemplation to appoint a suitable character to supply his place. Another bill of your Excellency's…drawn for erecting an assaying Furnace has not been protected…. The President has been consulted and the observations herein contained have his approval….96

The military part of the expedition had a designated point and purpose, but Tillier and Bates were emphasizing the commercial and military combination, which ran counter to the use of public funds. Lewis had not explained the plan to the War Department because it had been previously approved and sanctioned by Dearborn in 1807. When Simmons charged Lewis that he had not complied “in all practicable cases,” Lewis hadn't been advised of the government mandate of quarterly expenditures until after he sent the bills. The accountant refused five drafts, which amounted to $1,242, in his letter of July 15, 1809, four of which had been preapproved by Dearborn in March 1808.97

One can only imagine what Lewis was feeling when he read Simmons's refusal—with each sentence, his administration was unraveling before him. He responded to Simmons on August 18:

Yours of the 15th July is now before me, the feelings it excites are truly painful. With respect to every public expenditure, I have always accompanied my Draft by Letters of advice, stating explicitly, the object of the expenditure: if the object be not a proper one…I am responsible; but if on investigation, it does appear to have been necessary…I shall hope for relief.98

Penned by Jeremiah Connor, the sheriff of Saint Louis, because Lewis was sick with malaria and his shaking hands could not write legibly, Lewis's letter was seven pages and explained, point by point, Lewis's intentions in an attempt to refute the accountant's remarks.99 Letters of advice had accompanied every one of his drafts since his arrival in Saint Louis. On the last page of the letter, Lewis spoke about missing correspondence that he had sent to Washington to which he had not received an answer. “I have reason to believe that sundry of my Letters have been lost, as there remain several important Subjects on which I have not yet received an Answer.”100 His July 8 letter was never received; two others written in 1808 arrived with their contents missing; others arrived just before his death in October; and one arrived after his death.101

Lewis personally paid for the expenses of publishing the laws.102 On August 29, 1809, he met with the legislature and laid before them an account for printing and translating the laws of the territory in the amount of $1,5 24.57.103 The following day the legislature approved the bill, but it does not appear when he was reimbursed, or if Lewis paid Peter Provenchere the $560 owed to him.104 Provenchere wrote to his father on December 21, 1809, complaining that he hadn't been paid:

The disastrous death of our last Governor, while he was himself on a voyage from here to Washington, and who was a debtor of Mr. P. Ch. [Pierre Chouteau] of a very consequential sum, has put the latter in such a constrained position that whatever connections were between the two of us, would make it useless for him to employ me as before. I am, then, reduced in St. Louis to working for his elder brother [Auguste Chouteau], work of not enough consequence to fully occupy me. After all this, you can judge what my position is and see that I am really forced to leave St. Louis…. The death of Governor Lewis is again a misfortune for me, for because of his influence, I would have obtained something to do, although actually his conduct…was disapproved by the government. I lost hope, then, of getting anything.105

With expenses piling up and his reputation on the line both in Saint Louis and in Washington, Lewis knew that he had but one chance to salvage his personal honor and preserve his chances for a future career, and that was to go to the nation's capital to explain himself to the president and to confront Accountant Simmons about his unreimbursed drafts. Lewis departed Saint Louis on September 4 with the intent of going to Washington by water, but upon reaching Fort Pickering at the Chickasaw Bluffs on September 15, he rested for two weeks, as he had been stricken with a bout of malaria. Capt. Gilbert Russell, the commanding officer of the fort, took care of him and wanted to accompany Lewis to Washington.

During his stay at Fort Pickering, Lewis had changed his mind about traveling any further downriver. New Orleans had been struck with a malarial epidemic and would be a most unhealthy place to be. Lewis continued overland to try to reach Washington and died on his way there, never having had his face-to-face meeting with the officials who could have cleared his name and his financial health.

The career of William Simmons was not yet ended, however, and his parsimonious and autocratic reign was destined to ruin or end more lives. Dr. John M. Daniel, the hospital surgeon stationed in New Orleans, worried about the outbreak of malaria there, requested of Simmons the establishment of a small hospital. Predictably, Simmons replied that there was no need and that “there is not any other post within the US [containing] a body of troops sufficient to require or justify such an establishment.”106 By November of that year, more than 700 soldiers had died in New Orleans from the epidemic.107

At the beginning of 1809, a Capt. Thomas Van Dyke was ordered by the War Department to move his troops to a fort in eastern Tennessee. Simmons rejected the entire amount of a $623 bill submitted by Van Dyke for the relocation. Van Dyke mirrored Lewis's angst when he wrote in August 1809:

I feel conscious of having exercised my best judgment for the promotion of my countries interest and true good—from the subsequent statement & facts I still hope to impress you with the same belief…in addition to those [facts] mentioned it may not be improper to observe, that having a large family to support, & dependent on my pay alone, for that support, my situation will be extremely embarrassed, without my accounts are admitted.108

After Lewis died, several Saint Louis residents brought suit against his estate to recover their debts. When reviewing Lewis's lawsuits in 1810 and 1811 and Lewis's estate papers, there was no mention of a debt from the territorial legislature. There were other expenses that Simmons, the secretary of state, and the secretary of the treasury refused to pay, which amounted to about $3,800 out of Lewis's pocket that were never reimbursed. The refusal of these expenses ushered in Lewis's financial ruin, which had started with his trying to fulfill the land ownership requirement of his post through the purchase of extensive land holdings in the territory.109

From 1810 to 1812, the US government acknowledged many of the drafts that Simmons refused, and these were paid to Lewis's estate.

A chart showing some of the bills incurred by Governor Lewis later reimbursed by the government:

If Simmons had followed treasury and congressional protocol, Lewis would not have incurred these debts, but in the last three months of his governorship, he faced unspeakable anxiety, misfortune, and embarrassment. Simply put, Simmons's unchecked power degraded the life of a great man in the service of his country.

EPILOGUE

William Eustis served as secretary of war until after the start of the War of 1812, when, in the midst of trying to prepare the nation for a sudden war and military defeats on the battlefield, he resigned from office due to public pressure. In 1813, President Madison replaced him with the far more experienced John Armstrong. Armstrong was known to be a tough, no-nonsense, but even-tempered individual, but he clashed often with Simmons. On January 3, 1814, Armstrong brought the nature of Simmons's tenure to the attention of a congressional committee whose mandate was to investigate the abuses that had occurred from the “many defects in the organisation and practice of the Accounting branch of this department.”114 Armstrong wanted the committee to propose a bill establishing that

the expending departments of the government ought to have…little…to do with the settling of accounts and that balances…due to individuals…with the United States should be…found by the Accounting officers of the treasury department.115

In the past, the secretary of war was obliged to sign warrants before the accountant fulfilled his duty, which resulted in great abuses against such government officials as Meriwether Lewis, Capt. Samuel Vance, Thomas and Cuthbert Bullitt , Gen. James Wilkinson, Capt. Gilbert C. Russell, Pierre Dorion, William Clark, Pierre Chouteau, Peter Provenchere, and Capt. Thomas Van Dyke. The attorney general prepared a bill according to Armstrong's instructions and delivered it to the Senate, but it was set aside with the comments indicating

that the provision already existed; that the law commanded reports of Accountants to be submitted to the officers of the Treasury department for examination and revision; that this was obviously and wisely intended as a check upon these reports and that to ensure this end, warrants…could not be legally drawn until after such examination and revision had been made, and that otherwise the check upon the haste, the errors or the corruption of Accountants, contemplated by the law would be lost and the provision itself become a mere fiction.116

Ezekiel Bacon, the comptroller of the treasury, having received this note from Armstrong, wrote to Simmons and reprimanded him for settling and revising accounts, especially a large one from the deputy commissary of purchases:

[T]he adoption of such a course of proceedings…appeared to be entirely novel in itself, & inconsistent with the whole system of accountability which has heretofore been prescribed by this Department of their own government, as well as for that of the Accounting Officers of the War Department.117

Bacon reiterated the various sections in the act of Congress that regulated Simmons's duties, which provided “that the Accountant to the Department of War shall report from time to time all such settlements…for the inspection and revision of the accounting officers of the Treasury.”118 Simmons had not observed that provision since 1802 because he thought it wasted time.119 Armstrong believed that the practice fell “under the head of deficient morals.”120

Armstrong had met with Simmons and told him that he would not sign any more warrants until each and every account was approved by the Treasury Department. One of the clerks in Simmons's office brought several reports accompanied with warrants to sign, but Armstrong “tore them up with great violence, and put them in the fire,” and returned the rest to the accountant.121 Armstrong then discussed the matter with President Madison on June 29, 1814, explaining that many officers in the government shared his concern and “that I could multiply proofs of this sort of mischief and misrepresentation—from three to three hundred.”122

Armstrong provided what Dearborn did not—proof. He described an account of one officer where Simmons refused to sign a warrant for $3,500, “and which, after eight journies to this place, would have enabled him to discharge debts incurred in public accounts two years ago.”123 Armstrong also wrote about the abuse that Simmons had waged on Wilkinson for five years and mentioned other accounts.

President Madison wrote to Armstrong a week later, and in a four-page letter described many aspects of Simmons's duties, including the requirement of submitting quarterly accounts to the Treasury, the reason for warrants, what they meant, and their legality and usage. Armstrong thought that the signatures on the warrants were essential to the final settlement of an account, but Madison stated that they only provided authenticity.124 After Madison replied to Armstrong, the president sent a brief letter to Simmons: “It being requisite that the office of Accountant to the Department of War be placed in other hands, you will consider it as ceasing to be in your's after this date.”125

Finally, justice had been meted out, but it was too late for a dedicated individual like Lewis. For over a decade, one person with too much power had been able to negatively affect the governance of the country, the administration of the nation's defense establishment, and its mechanism for diplomacy with Native American tribes. How many persons did Simmons flatly refuse to pay, and how many accounts were arbitrarily modified or delayed in the far reaches of the empire? Simmons's office reviewed thousands of transactions yearly.126 As we have seen, the fanatical machinations of this one man led to the deaths of innocent men from disease, and can be cited as a major contributing factor to the death of the governor of the Louisiana Territory, Meriwether Lewis.127