Since Meriwether Lewis's death in the Tennessee backwoods on October 11,1809, tremendous interest has fueled endless speculation about how events unfolded during his journey from Fort Pickering (modern-day Memphis) to Nashville, Tennessee. Writers and historians have determined from reading official correspondence that Lewis's demise was somehow intricately linked to Maj. James Neelly, the Chickasaw Indian agent who traveled with him. They have also employed a plethora of guesswork to try and discredit Neelly, to question the route that he and Lewis took when they departed Fort Pickering, to instill doubt about the events at the homestead of Robert Grinder known as Grinder's Inn, and to assert that the letter Neelly wrote from Nashville, informing Thomas Jefferson of Lewis's death, was a cover-up.1

Given these accusations from leading historians that discredit Maj. James Neelly, it is important to establish who James Neelly was as a historical figure, whether or not he actually accompanied Lewis during the explorer's final days of life, and if he was the author of the letter to Thomas Jefferson describing Lewis's death.

Up until the present, James Neelly was an easy target for criticism because little information had been found about him. This criticism resulted in a skewed conception of his conduct when he was the Chickasaw Indian agent from July 1809 to June 1812.2 Recently, a program on the History Channel presented documentation that supposedly placed Neelly in a courtroom fifty-five miles away from Grinder's Inn on October 11, 1809, the date of Lewis's demise.3 This new information and the way in which it was presented might lead persons unacquainted with the details of Neelly's life to believe that Neelly lied to Thomas Jefferson in his letter about Lewis's death; it might even lead to wild speculation that he was involved in Lewis's murder—or was at the very least an accomplice. If it is true that Neelly was in court and not at Lewis's side, the order of events, including Neelly's arrival at Nashville on October 18, would be thrown into doubt, exacerbating the mystery of Lewis's final days.

However, as in many other instances involving historical mysteries, dogged research can uncover hitherto unknown sources. A danger inherent in this statement is encapsulated in the word “dogged”; partial research involving single documents taken out of context can often result in worse misconceptions than those that had existed when there was a vacuum of historical knowledge. Thorough research of a topic, approached through traditional and nontraditional types of documentation, can yield new and enlightening perspectives on the past, while half-baked efforts can lead to dangerous misconceptions and false conclusions.

In order to properly tell the story of James Neelly's involvement in the final days of Lewis's life, we first have to examine the development of the Natchez Trace, which ultimately led to James Neelly's appointment as an Indian agent and his timely arrival at Fort Pickering in 1809.

The Natchez Trace was an important wilderness road leading from Natchez to Nashville; it was also known as the Old Natchez Trace, Chickasaw Trace, or the Columbian Highway.4 It had begun as an Indian trail or a game trail that cut through the present states of Mississippi and Tennessee and wound through land that was occupied by the Chickasaw and Choctaw Indians.5 According to historian Arrell Gibson, the Natchez Trace served as “a strategic land bridge connecting the Cumberland and Ohio River settlements with the lower Mississippi Valley and Gulf.”6 It had been hewn out of the Mississippi and Tennessee wilderness and was considered unsafe because it “exposed the traveler to dangers of the natural elements, disgruntled Indians, and—worst of all—attack by notorious highwaymen and murderers.”7

In 1797, the United States government signed a treaty with the Chickasaw Nation, the stated purpose of which was to exchange land for goods, but with the unstated primary goal of opening the Natchez Trace as a major postal route and thoroughfare for travelers. Work on what was then referred to as the Natchez Road-commenced in 1802 and took a decade to complete.8 In the process of building out the road, large numbers of squatters encroached upon Chickasaw soil. This encroachment led to the passage of laws under the aegis of the US Department of Indian Affairs, which regulated the intercourse and commerce with the tribes. In an effort to prevent squatting, the department appointed an Indian agent to reside among the Chickasaws who would serve as their intermediary and report crimes against them and incursions upon their land back to Washington.

The Chickasaw Indian Agency was established in the Mississippi Territory, near a thriving Chickasaw village called Big Town, halfway between Natchez and Nashville, near modern day Okolona, Mississippi, at milepost 241.4 of the Natchez Trace Parkway.9 In May 1802, Henry Dearborn, the secretary of war, described the numerous duties and responsibilities of the Chickasaw agent:

The motives of the Government for sending Agents to reside with the Indian Nations, are the cultivation of peace and harmony between the U. States, and the Indian Nations generally; the detection of any improper conduct in the Indians, or the Citizens of the U. States, or others, relating to the Indians, or their lands, and the introduction of the Arts of husbandry, and domestic manufactures, as means of producing, and diffusing the blessings attached to a well regulated civil society: To effect the foregoing important objects of your Agency, you will use all the prudent means in your power. Suitable measures should be pursued for introducing the use of the plough, and the growth of Cotton as well as Grain. A Woman well calculated for the business should be employed in teaching the females spinning and weaving, and other household Arts; the use of Spiritous Liquors you should discourage by precept, and example…. You will refer to the Act passed the 30th March 1802 entitled an Act to regulate trade…to preserve peace on the frontiers.10

These agents also took charge of a subset of responsibilities that related to internal problems, such as insuring peaceful travel through Indian lands, collecting debts, recovering stolen horses, removing trespassers, and capturing fugitives.11

By 1808, the Chickasaw Agency was large and contained “a stable, granary, and fodder loft,” and still later, “a blacksmith's shop, and shelter to house the spinners and weavers.”12 There were also houses for the Indian interpreter, Indian agent, weaver and instructor of husbandry, blacksmith, and a lodge for visiting Indian dignitaries. James Neelly, the fourth Chickasaw Indian agent, succeeded Thomas Wright in 1809.13 Wright had succumbed to a severe attack of the ague on August 10, 1808, and at the end of September he died from it.14 A few months later, in February 1809, George Colbert, half Chickasaw and “chief negotiator” of that nation, recommended Neelly to Secretary Dearborn:

Father if you would be so good as to indulge us, we could recommend an old Gentleman of our acquaintance that is not so fond of Speculation, as our former agents have been, his name is Maj. James Neely but perhaps it may be too forward in us to recommend any person to Government—therefore we will leave it to your superior judgment to send us a good man…we would prefer an Elderly man as an agent as young men in the heat of youth may abuse your authority, there has been an instance of that already, in this nation of an agent going wrong, the red people wished to put him right & he threatned us with the Government & the Laws therefore we conceive that an Old is more suitable to do business with red people than a young man.15

Colbert's use of the word speculation meant other nefarious activities, too: a former agent had established a tavern at the agency to supplement his income by selling liquor, while others were known to engage in private trading.16 Colbert himself operated a ferry forty miles from the Chickasaw village near modern Tupelo, Mississippi, where the Natchez Trace crosses the Tennessee River.17 The river was deep at this place, with a rapid current that made it “impossible to ford,” and Colbert made a good income from this business—about $2,000 annually.18

Having not received an answer from the secretary of war, Chenubbee Mingo, the king or headman of the Chickasaws, followed with another letter to Dearborn explaining the necessity of a Chickasaw Indian agent, the constant trespassing of intruders on Chickasaw land, and the distribution of their annuity:19

Father: after the death of our late Agent last fall we petitioned the Government of the United States to send us an Agent, a good sedate sober man from some one of the old states, & we have never received any answer as yet.—the reason why we did petition for such an Agent, was that some of the individuals of the neighbouring states, are a good deal inclined to land speculation—for instance gentlemin from near franklin Tennessee by the name of Potter & whom we heard had petitioned to Government for this Agency has with some others been in our land hunting old lines, at least fifty miles within our boundary line this makes us believe that were we to have any Agent from any of the neighbouring states they might be guilty of the like Practices…our Annuity for the last year has been laying at the Chickasaw Bluffs above twelve months & we are afraid it may be damaged—if the President our Father would be pleased to authorize the officer Commanding fort Pickering or any other person that he may think proper to deliver it to us—we will take it as a particular favour & as an instance of his Parental kindness to his red Children the Chickasaws.20

Return J. Meigs, the Cherokee Indian agent, had been assisting the Chickasaws since Wright's unexpected illness and death. He explained the utmost urgency to fill the position of Chickasaw agent in a letter to the secretary of war dated June 12, 1809: in June 1809 he had to remove ninety-three families, all farmers, from Chickasaw land.21 Although these family groups were compliant, there were others who were an aggressive and feared lot:

The great length of this frontier & the few troops in this quarter, puts it in the power of lawless characters to impose on the Indians & to put the U. States to considerable expence. Should this disposition to encroach on Indian lands increase, they will perhaps at some future period put the few troops here at defiance. These intruders are always well armed, desperate characters, have nothing to lose; & many of them hold barbarous sentiment toward Indians. They see very extensive tracts of forrest held by the Indians imcullivated, disproportioned to the present or even expected population of the tribes, they cannot purchase lands. They plead necessity in the first instance, & if the land should be purchased of the Indians will plead a right of preemption making a merit of their crimes.22

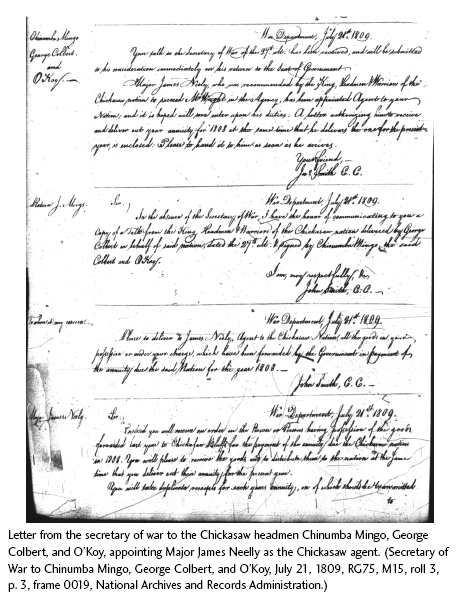

Finally on July 7, 1809, the secretary of war took the advice of Colbert and appointed James Neelly as Chickasaw Indian agent at the standard rate of $1,000 annually and $365 for subsistence.23

Neelly did not receive the news until August 8, when Gen. James Robertson, the commissioner of Indian affairs from Nashville, delivered the commission in person at his home, a few miles from Franklin, Tennessee.24 Neelly, who held the rank of major in the Tennessee militia, was from Duck River, outside Franklin. During the three years that Neelly served as Indian agent, he remained faithful to his appointment, which is not surprising, since he was closely allied with the regional government in Williamson County, Tennessee. In February 1800, when the Court of Common Pleas and Quarter Sessions was established in Franklin, Neelly was immediately enlisted as a juror in civil court, appointed a juror in the Superior Court, and he collected taxes for Capt. Gordon's Company until his appointment as Indian agent.25 Neelly's commission also contained an extensive letter from the secretary of war, which included orders to hasten to his post and take command of the agency and buildings. When the former agent, Wright, suddenly died, the War Department routed the annuities due to the tribe to the factor at Fort Pickering, 150 miles northwest of the agency.26 It was essential that Neelly, when he completed his initial work at the agency, depart post haste to meet with the Chickasaw chiefs, then travel to the fort, meet with the factor, pick up the articles for the Chickasaws, and return to the agency to distribute them.27

On July 21, the War Department acknowledged the letters from the Chickasaw chiefs and informed them of the new appointment:

Maj. James Neelly, who was recommended by the King, Headmen & Warriors…to succeed Mr. Wright in the Agency, has been appointed Agent to your Nation; and it is hoped will soon enter upon his duties. A letter authorizing him to receive and deliver out your annuity for 1808 at this time that he delivers the one for the present year, is enclosed: Please to hand it to him as soon as he arrives.28

The War Department instructed Maj. Neelly to take possession and distribute the annuities for 1808 and 1809, which covered a vast quantity of materials.29

Neelly's first month as agent was packed with chores and travel. The Chickasaw Agency was due south from Neelly's home on Duck River on the Natchez Road, and Neelly arrived there about August 26.30 The following day he assessed the agency property and reported dismal conditions regarding the office and residence:

After my arrival at this place I viewed the Public Buildings in hopes to find a Comfortable house to live in but to my surprise I only found the remains of a house that is an old shell, the roof at first was covered with what workmen call lap shingles, there is part of them gone & all the remainder loose, the Sleepers are all rotten & not worth repairing. by the best judgment that I can Collect to view it—the bottom logs of the smoak house are rotten & the kitchen is in a decayed state—from a letter that I found among Mr. Wright's papers from Henry Dearborn Esqr. your predecessor in Office a letter in answer to a letter from Mr. Wright respecting permission to repair or build an addition to the agency house Mr. Dearborn's letter directs him to make such Economical repairs or addition to the Agency house as he might think proper—I suppose on the strength of that letter Mr. Wright in his lifetime had got a frame almost complete ready to be raised as an addition to the Agency house which frame is still lying here unfinished—on viewing the plan I percieve his intention was to keep public entertainment which would have given great umbrage to the Indians as they wish to reserve that business soley to themselves for the benefit of the nation it is said that Mr. Wright had began the business & that the Indians would soon have drove him, had not death taken him off. now sir if you forbid it not I think the best plan would be to put up the new frame in place of the Old one—as I cannot think of living in the old one there is no possibility of making it a safe or comfortable house to live in—this I hope you will advise me of as soon as practicable as the season is fast advancing should it not meet your approbation, I must, I suppose, live in a wigwam, Indian fashion—as I expect my board will be high until I get a house to put my family in.31

After making his assessment of the agency, Neelly prepared to fulfill his duty to the Chickasaws regarding their annuities, and purchased a government horse on August 30 for $125.32 He set out first to the Chickasaw village to make introductions and then headed to Fort Pickering to meet with David Hogg, the factor, and take possession of the annuities to return them for distribution. Maj. Neelly made good time on the 150-mile journey and arrived at the fort on September 18. There he learned that Governor Lewis had arrived by boat three days earlier, so ill that he required assistance to walk from the bottom of the bluff up the 120 square log steps to the fort.33

Maj. Neelly had never met Lewis, but because of a simple act of kindness, his life would be forever changed. Our knowledge of Neelly's involvement with the governor at the time of Lewis's death is based on various letters written to Thomas Jefferson, including those by Maj.Neelly himself.34 While at Fort Pickering, Lewis changed his mind about his preferred travel route to Washington, deciding not to proceed to New Orleans for an ocean voyage because, as he informed President Madison, of his “apprehension from the heat of the lower country.”35 Lewis's concern regarding “the heat” was an expression of his worries about malarial fever, which Lewis had already succumbed to in the beginning of August 1809, a month before departing from Saint Louis. Reports from New Orleans stated that the fever was rampant there, and in an era when medical knowledge of malarial fevers was limited, such areas were to be avoided by those coping with the disease. When Lewis arrived at Fort Pickering he was still sick with fever, which is known to incapacitate for several days.

Gilbert Russell, the commander of the fort, thought that he might be able to escort Lewis to Washington. He had been corresponding with the accountant of the War Department over a costly unpaid bill and had asked the secretary of war for permission to go to Washington to clear up the matter.36 Russell waited an extra week for the mail to arrive, thinking that his approval was forthcoming from the War Department.37 When the approval did not arrive, Neelly may have stepped in to offer his services to the ailing governor and hero of western exploration. Russell may have requested that Neelly, as a government employee, accompany Lewis, who was still very ill while staying at the fort. Russell was certainly very concerned over Lewis's condition. Exactly how Neelly's services were offered and accepted is unknown, but on September 29, 1809, Lewis, his servant John Pernia, a hired horsepacker, and Neelly departed Fort Pickering for the Natchez Trace.38

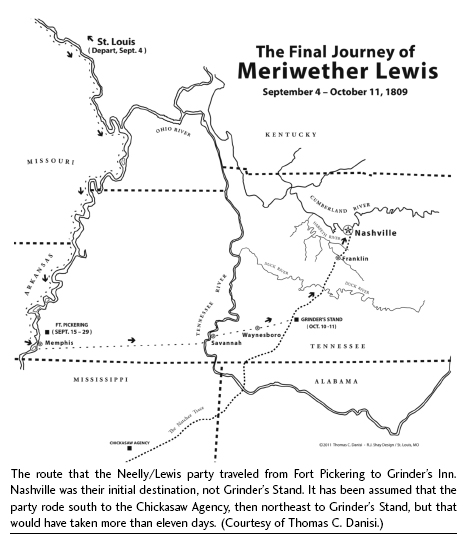

Some historians believe that the party first traveled to the Chickasaw Agency before turning north for Nashville, but that would have been physically impossible. Simple math dictates otherwise when considering the standard travel time on horseback of 10–15 miles per day and keeping in mind Lewis's physical condition. The agency was not on the direct route from Memphis to Nashville, and in fact was in the opposite direction. From Memphis to the Chickasaw Agency “as the crow flies” is about 110 miles, which would have been a much longer route over the twisting roads of the time.39 From the agency at milepost 241.4 on the Natchez Trace to Grinder's Stand, the inn where Lewis died at milepost 385, is 143 more miles, for a total of 253 miles. In a simple calculation of the distance at 10–15 miles per day it would have taken 17–25 days to reach Grinder's Inn by way of the Chickasaw Agency, instead of the eleven days they actually spent in travel.

Additionally, after they departed Fort Pickering, there were complications. Neelly stated that after crossing the Tennessee River, which is located at Savannah, Tennessee, Lewis became ill and the party rested for two days. The direct distance from Fort Pickering (Memphis) to Grinder's Inn is about 150 miles, and given an eight-day spread, only the most direct route would have allowed them to reach their destination. The party probably traveled the route of present day US 64.40

The party made their penultimate camp at milepost 375, and on the morning of October 10, Neelly remained behind to look for two horses that strayed the previous night.41 The party was approaching the area where Neelly lived. Since he was very familiar with the locale, he could have advised Lewis on October 10 about how to proceed until he could catch up and bring the lost horses. Neelly knew that a man named Robert Grinder had accommodations for travelers and that his “stand” or inn was not far—a day's ride.42

Late in the afternoon, Lewis and the two others arrived at Robert Grinder's house. In the early morning hours of October 11, Meriwether Lewis died. Maj. Neelly arrived the next day, reporting that “I came up some time after & had him as decently Buried as I could in that place.”43

Recently, Maj. Neelly's solid two-hundred-year-old account of the events has been challenged by a new interpretation of a historical court document, an interpretation that was aired on the December 9, 2010, presentation of Decoded for the History Channel.44 Tony Turnbow, an attorney who practices in Franklin, Tennessee, and the discoverer of the court document, alleged that Neelly was in a Tennessee courtroom on October 11, 1809, rather than on the Natchez Trace with Lewis. The Williamson County Court document shows that a lawsuit had been filed against James Neelly, who had been ordered to be in court on October 11 and thus could not have been at Grinder's Inn.45

Tony Turnbow very generously shared copies of the documents he relied upon in drawing his conclusions. In the preparation of this chapter, the court documents were utilized, as was the expertise of Tennessee attorney Caesar Cirigliano, who practices criminal and civil law in Williamson County today. Mr. Cirigliano's investigation of the documents revealed that Neelly had simply not been ordered by the court to be present on October 11, 1809. The minute book of the county court states:

Thomas Masterson & Co. vs. James Neelly. Debt $103.44 Dam. $20 This day came the parties by their attor & came also a jury of good and lawful men…who being elected tried and sworn the truth to speak upon the issue joined upon their oath.…46

Cirigliano explained that the county court minutes show that “this day came the parties by their attor”; in other words, the litigants in the civil suit were represented before the court by their attorneys, and the litigants did not have to be present. The legal wording is very exact: “came the parties by their attor.” The abbreviation “attor,” common at the time, was included in most legal writing from the county court minutes of Williamson County. This wording indicates that attorneys represented the parties at the courthouse on that date. It does not state or imply that the parties and their attorneys were both present; it is common practice, observed today as well, to waive the presence of the client in court when represented by counsel in a civil suit of this type.47

One other point must be made: How important was this trial to Neelly? Some might feel, from reading the document, that since Neelly was close enough to where the court met at Franklin, about fifty-five miles away, he might have been inclined to drop everything and go to court. However, this would be unlikely considering that Neelly had taken it upon himself to deliver the ailing Lewis safely to authorities at Nashville. Since Neelly would most certainly miss his day in court, how important was his appearance? What would be the ramifications if Neelly did not appear? Actually, nothing serious would have occurred except that he would have lost the case by default and would therefore have had to pay the amount of money for which he was being sued, which totaled $123.44 with damages. Although this was a substantial amount of money at the time, there is no evidence that it would have worried Neelly. And there is proof for this line of reasoning: On July 8, 1805, Neelly was called as a witness in a civil lawsuit. Neelly “was solemnly called but came not.” The court levied a fine of $125 unless he could show sufficient cause of his inability to appear and he was ordered to attend at the next court, which was set for January 17, 1806. On that day, Neelly “came not” and had to pay the fine.48 The case was a civil and not a criminal action, and Neelly was under no obligation to attend, as he had been in 1805 when he was subpoenaed as a witness to someone else's lawsuit. Although his attorney may have ably represented Neelly on the date in question, the court records reveal no further disposition of the case, which may have been dropped there after.

These two arguments, while clever in dismantling the impact and seriousness of Neelly's involvement, do not absolve him of wrongdoing and continue to reinforce the idea that he might have been underhanded in some way. The underlying problem with the lawsuit is that no identifying characteristics mark the James Neelly named in the suit. There is no information pertaining to age or date of birth, nor the location where he lived or worked. Furthermore, the discoverer of this document left too many questions unanswered. Who was James Neelly, and was he an honorable or dishonorable man?

As archaeologist and historian W. Raymond Wood ably wrote, “The truth is to be found in detailed detective work.”49 In an effort to corroborate Turnbow's assertion, deep research was conducted to fully understand the inconsistencies. The Williamson County clerk at the time of the Neelly suit was Nicholas P. Hardeman, who also operated a merchant store in Franklin, Tennessee, with his brother. The Hardemans ran a brisk business with many of the locals, including an extensive number of individuals by the name of Neelly. Taking a sample of the Hardemans’ accounts from this time period, fourteen Neellys are revealed to have transacted business with the store. The Hardemans made particular identification for four Neellys with similar names: Maj. James Neelly, James Neelly Sr., James Neelly Jr., and James Neelly, Esquire.50

The lawsuit papers that Turnbow provided originated from the Williamson County Court files and County Clerk Minutes record book. The County Clerk Minutes record book spans the years from 1800 to 1815 and interestingly contains many entries with the name of Neelly. For instance, on January 13, 1807, there are two separate Neelly entries regarding the repair of a road, which corroborates the identifications in the Hardeman accounts. The entries stipulate the “keeping in repair [of] the public road lately laid from Jas. Neellys to Cannons horse mill…,” while the other entry calls for “keeping in repair the public road from…N. P. Hardemans land to Duck river ridge…to the mouth of Maj. James Neellys spring branch where it enters into Murfrees Fork….”51

One court document viewed in isolation should not be enough evidence to dismantle an honorable man's reputation. The fact that four James Neellys were living in the same area at the same time casts doubt upon whether the defendant in the October 11, 1809, lawsuit was even the same James Neelly who was Chickasaw Indian agent and accompanied Lewis from Fort Pickering.52

On October 11, 1809, after burying Lewis, Maj. Neelly and party departed Grinder's Inn and made their way to Nashville with Lewis's belongings. It was probably one of the most grueling and tragic weeks of Neelly's life. Within a day's ride and minus two horses, they had to cross another large river and then travel over rough terrain: “Duck River was fordable and once over it the Trace struck boldly into the mountains that made up most of the 50 miles to Nashville. Travellers had to dismount at this stage and get along the best they could on foot through sandy soil that played sad havoc with their feet.”53

Ten miles from Nashville the Trace crossed the Harpeth River, which was “fifty yards wide” and “the road widened, announcing the nearness of a settlement.”54

They arrived about October 18 in Nashville, where a small US trading post had been established years earlier.55 A special agent of the United States, Capt. John Brahan, receiver of public monies, was Neelly's local superior, and Neelly reported the details of Gov. Lewis's death to him. It has been a mystery to historians why Capt. Brahan was in Nashville and not with his company of soldiers. However, it may be of some interest that Albert Gallatin, the secretary of the treasury, had temporarily appointed Brahan to a nonmilitary position. Gen. James Wilkinson even complained to the secretary of war about Gallatin's over-reaching authority in June 1809:

One of my Captains, Brahan, at Columbian Springs, has been appointed by Mr. Gallatin a receiver of public monies for the sale of lands some where. He has received his appointment & instructions whilst at the head of his platoon. I respect the authority from whence they emanated too much to counteract the intention, & have therefore given him leave of absence without forcing a resignation; but I must believe it is not exactly correct, to take our officers from us without our privity or approbation.56

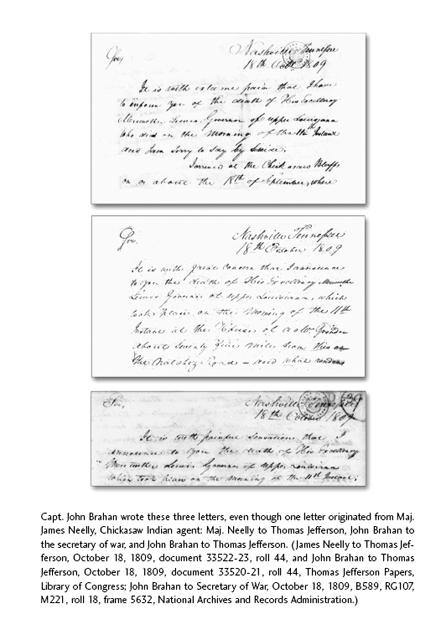

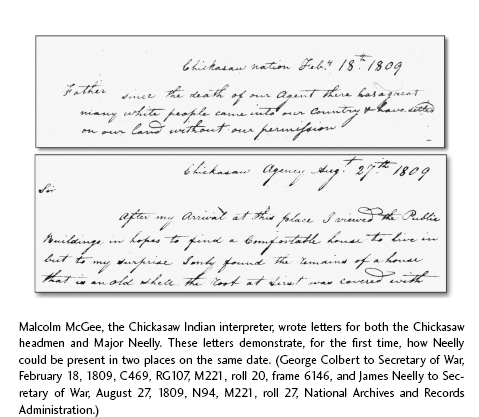

On October 18, 1809, letters were written to Thomas Jefferson and to the secretary of war detailing the tragic news.57 What has not been uncovered until now is that Brahan wrote not only letters of his own but Maj. Neelly's letter as well. This oversight explains some of the apparent dates where Maj. Neelly was in two places on the same date. While Maj. Neelly was an Indian agent, for instance, Malcolm McGee, the Indian interpreter at the agency, wrote almost all the letters for Neelly, Chinumba, and Colbert. For the first time it makes sense how Maj. Neelly could have been in Nashville on October 18 and also have a letter with that same date written from the Chickasaw Agency.58

While it has been thought that Maj. Neelly was somehow a suspicious figure and had possibly lied or attempted a cover-up in regard to Lewis's death, it has now been proven by authentic documentation that he was an ordinary man somehow embroiled in a suspected murder because of errant speculation. At the end of September 1809, Maj. Neelly, busy organizing an Indian agency, trying to do justice to his government appointment and the Indian people who requested his services, volunteered for a thankless assignment that has met with extreme controversy for at least a century, but now, hopefully, has been more fully explained.