Various documents connected to Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, and the Corps of Discovery in the form of letters, official reports, and period newspaper articles, have garnered special attention over the course of many years of intense study. One document, intricately linked with Lewis's death in 1809, has received a great deal of notoriety as a result, yet its background is a mystery to historians. Known as the “Gilbert Russell Statement,” it is a four-page document detailing the circumstances of Lewis's death, an event that has baffled historians for two centuries.1

In 1811, Gilbert Russell, an officer in the US Army, was ordered by the secretary of War to Fredericktown, Maryland, to attend Gen. James Wilkinson's court-martial. The trial was convened because hundreds of soldiers had perished from malaria under Wilkinson's command during the summer and autumn of 1809. Russell provided testimony at the trial to establish Wilkinson's character and, during this same trip, also gave a statement regarding Lewis's death, which had occurred two years previously. Russell had personal knowledge of the events surrounding Lewis's death because he had been the commander of Fort Pickering (near today's Memphis, Tennessee) when Lewis passed through that post in 1809. Fort Pickering was the last habitation where Lewis was seen prior to his death. A knowledge of his actions and behavior at the fort is crucial to understanding the events that unfolded a few days later when Lewis died along the Natchez Trace, en route to Nashville.

What has not been properly addressed by historians is that the Russell Statement is a recollection of the event, not a firsthand report, and Russell's version of the story was composed not only from his own experiences, but also from interviews he conducted with various persons who conversed with Lewis at Fort Pickering and knew of events that had taken place along the Natchez Trace and at Grinder's Stand, the scene of Lewis's death. These eyewitnesses to various portions of the story included Maj. James Neelly, David Hogg (the factor at Fort Pickering), and Dr. William C. Smith, the surgeon's mate at Fort Pickering. Russell's recollection was also based upon reading newspaper reports and his correspondence with officials like Thomas Jefferson and William D. Meriwether, the administrator for the Lewis estate.

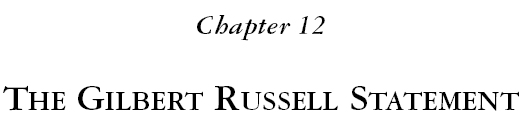

The Gilbert Russell Statements begins :

Governor Lewis left St. Louis…early in September 1809, intending to go by the route of the Mississippi and the Ocean, to the City of Washington, taking with him all the papers relative to his expedition to the pacific Ocean, for the purpose of preparing and putting them to the press, and to have some drafts paid which had been drawn by him on the Government and protested. On the morning of the 15 th of September, the Boat in which he was a passenger landed him at Fort pickering in a state of mental derangement…. The Subscriber being then the Commanding Officer of the Fort on discovering from the crew that he had made two attempts to Kill himself, in one of which he had nearly succeeded, resolved at once to take possession of him and his papers, and detain them there untill he recovered…. [O]n the sixth or seventh day all symptoms of derangement disappeared and he was completely in his senses…. On the 29th of the same month he left…with the Chickasaw agent…and some of the Chiefs, intending to proceed the usual route thro’ the Indian Country…. [I]n three or four days he was again affected with the same mental disease….2

In the year 2006, historian James Holmberg had difficulty describing the document because he did not know “why the statement was given.”3 Those who suggest that Lewis was murdered in 1809 generally believe that the Russell Statement is a forgery and have suggested two incidents with which it is supposed to coincide: a revisionist version of Lewis's final days, and the identification of Brig. Gen. James Wilkinson, the commanding general of the United States Army, as Lewis's murderer.4

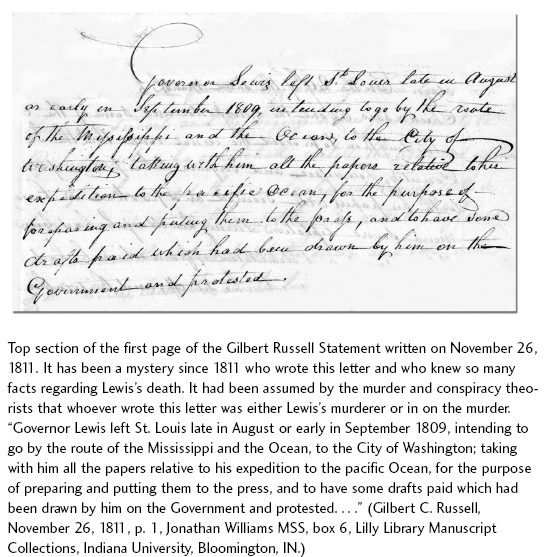

The Russell Statement describes the route Lewis took from Saint Louis to Fort Pickering in September 1809. It describes his behavior during that time, his departure to Nashville, and the events leading up to his death on October 11. The statement bears the signatures of Gilbert Russell and a man named Jonathan Williams, another army officer, but neither the text nor the signature are actually in Russell's hand. Russell had penned two earlier letters in January 1810, both sent to Thomas Jefferson, which detailed the events leading up to Lewis's death.5

Comparing the handwriting in the two Russell letters of 1810 with this 1811 statement, even a layman can see that two entirely different people penned them.6 The discrepancy in handwriting led to a presumptuous and controversial conclusion on the part of conspiracy theorists, wherein it was claimed that whoever wrote the 1811 statement possessed such intimate knowledge of so many crucial details of Lewis's murder that he must have been Lewis's murderer—or at least in on the conspiracy to kill him. To the untrained eye the Russell Statement is truly an enigma. Who was its author? Who possessed such detailed knowledge about the circumstances surrounding Lewis's death? Why was the document written? Was the author the long-rumored murderer of Meriwether Lewis?

After searching through many archival collections for clues regarding this mystery, the Russell Statement must be considered as a completely authentic document that represents the viewpoint and experience of Capt. Russell. It is not in his handwriting because it is a legal document—an affidavit, which is a sworn statement administered in a court of law. The evolution of this important document begs for a comprehensive explanation.

Capt. Russell assumed command of Fort Pickering in June 1809.7 During the next few months he wrote letters to the US secretary of war complaining about the deplorable condition of the fort, frequent sickness, and the inefficient surgeon of the garrison.8 He reported in August that the ague and fever, known as malaria today, had depleted his troops to the extent that but eight or nine of them were fit for duty.9 Less than a month later, Lewis arrived at the fort, also extremely sick from the ague, and he recuperated for nearly two weeks under Russell's care.10 Maj. Neelly, who was appointed US agent to the Chickasaw Nation on July 7, 1809, and was a significant figure in the story of Lewis's death, arrived at Fort Pickering for the first time on September 18.11 Neelly accompanied Lewis on his overland trip east, eventually arriving at Grinder's Stand, the place of Lewis's demise.

During the two weeks that Lewis resided at Fort Pickering, Russell, much concerned about his condition, wrote to his commanding officer asking for a furlough in the hopes that he could accompany Lewis to Washington. Russell later told Thomas Jefferson that “I had made application to the General & expected [a] leave of absence every day to go to Washington…with Governor Lewis.”12 Historians have guessed that Russell was referring to Gen. James Wilkinson, but that is an incorrect assumption.

Wilkinson was stationed in New Orleans during that time, and it took four weeks for mail posted from Fort Pickering to arrive in that city. What actually happened was that Russell received orders to move his company to Fort Pickering in March 1809, and when he did, he sent William Simmons, the accountant of the War Department, an expense account of the trip. Simmons denied the expenses and Russell then asked the secretary of war, Gen. Henry Dearborn, for a furlough to come to Washington and discuss the account.13 Russell had had a similar problem with Simmons a few years earlier.14

When Russell told Jefferson that he requested a furlough, he was referring to the expense account problem. He had hoped that the furlough was imminent but he had only been at Fort Pickering a little over three months, and with his garrison so sickened by malarial fever he could hardly have expected approval to leave his post. However, if true, the request reveals how genuinely concerned Russell must have been about Lewis's condition, knowing that when Lewis continued on toward Washington he would need a reliable protector, perhaps an experienced nurse if he had a relapse, and someone who realized the horrible nature of Lewis's attempts to alleviate his pain while burdened with fever. Since Russell could not leave his post, he had to settle for sending Maj. Neelly as a surrogate to fulfill these roles.15 Russell, still at Fort Pickering over a year later in November 1810, wrote once again to his superiors and repeated his desire to visit Washington.16 Perhaps this request also involved the now-deceased Lewis, for Russell had a tale to tell regarding Lewis's final days that he alone was privy to.

Russell's account of his experiences with Lewis during the two weeks at Fort Pickering is corroborated by another, rarely cited, original document in the collections of the Missouri History Museum in Saint Louis. It is a letter written by a man named James Howe to Frederick Bates, secretary of the Louisiana Territory, on September 28, 1809, from Nashville, Tennessee. Note the date; the letter was written thirteen days before Lewis's death by a man who had no particular interest in the matter other than passing along distressing information and lamenting Lewis's condition. Although the information reported is third hand, it is crucial evidence because it was written prior to Lewis's death:

I arrived here two days ago on my way to Maryland—yesterday Majr Stoddart of the army arrived here from Fort Adams, and informs me that in his passage through the indian nation, in the vicinity of Chickasaw Bluffs he saw a person, immediately from the Bluffs who informed him, that Governor Lewis had arrived there (some time previous to his leaving it) in a state of mental derangement, that he had made several attempts to put an end to his own existence, which this person had prevented, and that Capt. Russell, the [commanding] officer at the Bluffs had taken him into his own quarters where he was obliged to keep a strict watch over him to prevent his committing violence on himself and had caused his boat to be unloaded and the key to be secured in his stores.

I am in hopes this account will prove exaggerated tho’ I fear there is too much truth in it—As the post leaves this tomorrow I have thought it would not be improper to communicate these circumstances as I have heard them, to you.17

While Russell dealt with problems at Fort Pickering, downriver Gen. Wilkinson was about to become embroiled in a tragic situation that he could not have prevented. The War Department at the end of April 1809 ordered Wilkinson to move the troops in New Orleans up the Mississippi River to Fort Adams and Natchez. Wilkinson did not receive those orders on a timely basis and instead moved the troops twelve miles southwest of their encampment to Terre aux Boeufs due to the impending sickly season.18 The bilious fevers were strong that summer, however, and overtook the troops in their new location.19 Consequently Wilkinson was forced to move again but this time lacked boats and supplies, and by November 1809 more than 700 soldiers had died of the illness.20 A physician caring for the sick troops testified that “a number [of them], in a state of delirium, wandered from their lodgings into the fields and swamps and there expired.”21

Murder theory proponents claim that Wilkinson orchestrated the murder of Governor Lewis from afar, but moving 2,000 troops to two separate cantonments in succession was an enormous and time-consuming undertaking. The second move proved more dangerous: Wilkinson did not have enough boats to ferry the sick, and the boats that arrived on August 17 from Fort Adams were leaking and “in very bad order and some almost rotten.” Lt. Samuel McCormick, who superintended the boats, said that they had to be refitted for service, and several new ones had to be built. “Rudders, oars, masts and sails were made and completed by September 10.”22 Wilkinson personally supervised their repair, attending “daily to urge the progress of it,” but in September, Wilkinson was stricken with the ague. Dr. Robert Dow explained that Wilkinson was confined to his bed and “had a remittent fever attended by very violent paroxysms,” and did not recover until the end of the month.23 Dr. William Hood visited Wilkinson several times in September and described the depth of his malarial attack: “[H]is state of convalescence was tedious owing, I believe, to the great anxiety of mind which he then appeared to labour under and then being, incessantly importuned on business.”24

Word of the massive mortality rate spread quickly, and President James Madison was appalled that Wilkinson failed to follow orders to protect his command. In April 1811, the House of Representatives appointed two committees, one to inquire into the fatalities and the other to investigate Wilkinson's public life, character, and conduct.25 The House determined that the government possessed enough evidence to put Wilkinson on trial, and President Madison approved the military court-martial to convene on the first Monday of September 1811.

Wilkinson chose a number of military personnel and civilians as defense witnesses, some of whom were well known: Maj. Amos Stoddard, Col. William Russell, Col. Jonathan Williams, Maj. Gilbert Christian Russell, Col. John Bollinger, William Claiborne, Capt. Daniel Hughes, George Mather, and Col. William Wikoff. Brigadier Geneneral Peter Gansevoort chaired as president of the trial, which began on September 2 and ended on December 25, 1811.26

Russell testified on three separate days in the same month: Tuesday, November 5; Wednesday, November 20; and Saturday, November 23, 1811. He maintained that Wilkinson's conduct during the years he was in the Mississippi and Orleans territories was exemplary and he also gave a character reference.27 The significance of the court-martial and its links to the Russell Statement, which was dated during this same period, was not apparent, however, until a crucial handwriting comparison was made. Looking at both the record of the court-martial proceedings and the Russell Statement side by side, one can easily see that they were written by the same person; the man who served as the clerk of the court-martial. There were several scriveners (court scribes) in attendance for the duration of the trial, so it is difficult to determine which of the named men this was; however, the handwriting was indisputably the same.28 And thus, on November 28, 1811, one of the court scriveners for the Wilkinson trial wrote in beautiful flowing penmanship Gilbert Russell's own statement of the events leading up to Lewis's death.

The remaining question was why did Russell provide such a statement during the course of the Wilkinson court-martial? To answer this question, the reader must first become acquainted with a little-known early American organization. The following people, all familiar to Lewis and Clark historians, have something in common: Amos Stoddard, William Russell, Jonathan Williams, Peter Gansevoort, William Clark, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, Samuel Latham Mitchill, Frederick Hassler, Zebulon Pike, James Wilkinson, and Meriwether Lewis.29 These persons were all members of the United States Military Philosophical Society, which was founded in 1802 by Col. Jonathan Williams, a grandnephew of Benjamin Franklin.30 The society's purpose was “to stimulate the collection and dissemination of military knowledge,” but Jonathan Williams eloquently wrote a more detailed description of the society's goals:

[T]o preserve for future generations the science which their fathers have obtained by dear experience on fields of glory.…It will become an immediate object to join to the institution the most respectable military and scientific characters of our country…and it is hoped that knowledge resulting from their honourable experience will be saved from oblivion, and secured among the archives of the society.31

The society began collecting important papers written in the field concerning new and ancient fortifications, harbors, floating batteries, or gun boats, boat designs, maps, canals, coast surveys, meteorological observations, barometrical measurements, mountain altitudes, and experiments conducted on musket barrels. The society sponsored publications and endorsed scientific works that gave them validity.32 There was also the occasional letter addressing future works like the one Samuel Latham Mitchill wrote to Williams at the end of December 1806: “I have just had a conversation with Capt. Lewis, who has just returned from his journey to the Pacific Ocean. He is a very interesting Traveller, and will in due time furnish us with a Book & Map of his Adventures and Discoveries.”33

At its inception, the United States Military Philosophical Society regularly held its annual meeting at West Point, then in New York City, and finally wherever a quorum was in attendance.34 By 1811, the society numbered about a hundred members, and a segment of its membership attended the Wilkinson court-martial. How fortunate that the most important person associated with Meriwether Lewis in September 1809 was at Fredericktown in a court of law. Jonathan Williams, who had been called as a defense witness, wrote copious notes during the trial.35 If you will recall, the second name appended to the Russell Statement is that of Jonathan Williams. Because of his active leadership of the United States Military Philosophical Society and his past inquiries and interest in Lewis's story, it was completely understandable that Williams would want to depose Gilbert Russell, a key witness, on one of the young nation's saddest and most important chapters.

On November 28, 1811, Gilbert Russell recalled the two weeks he spent with Lewis in the autumn of 1809 while the court clerk patiently scribed his testimony. Russell may have been reading from a document that he had previously compiled, which would establish that he already knew that he would be giving a sworn statement to Williams. If we look at the last couple of sentences of the 1811 statement, Russell declares, “His death was greatly lamented. And that a fame so dearly earned as his should be clouded by such an act of desperation was to his friends still greater cause of regret.” In April 1810 Thomas Jefferson had replied to Russell's two letters describing Lewis's demise by concluding, “We have all to lament that a fame so dearly earned was clouded finally by such an act of desperation.”36 It is obvious that Russell agreed with Jefferson's bitter sentiment, and even included a paraphrase of it in his 1811 statement.

One other piece of documentation removes any vestigial doubt of the authenticity of the Russell Statement. The paper that the Russell Statement is written upon and the paper that Jonathan Williams wrote his copious notes upon at the Wilkinson court-martial each bear the identical watermark: C. WILMOTT 1809.37

Because historians and other readers did not understand the nature of the Russell Statement, why it was written, and from whom the information came, they jumped to the conclusion that it revealed a specific historical figure to be a murderer, or at least to have ordered a murder. This was quite unfair to the already somewhat tarnished reputation of James Wilkinson. Ironically, Wilkinson was unwittingly the catalyst for the circumstances surrounding the creation of the statement, for it was written primarily because his court-martial brought together the various dramatis personae necessary for its creation; a witness to history, a person interested in the preservation, through official testimony, of the historical record, and an official scribe skilled in the taking of testimony for legal purposes.