One of the most fascinating and instructive recent discoveries regarding the life of Meriwether Lewis was his battle with malaria, which in his time was called “the ague,” an incurable and untreatable disease. Few examples of his illness have survived, mainly from the expedition journals and from official correspondence, but also from those closest to him who wrote about his condition. Definitive proof has now been found from the physician who cared for him from April 1808 to September 1809, the full term of his governorship while he was in Saint Louis. This is a remarkable discovery not only because it occurred in the year of Lewis's death, but also because the care was provided by a trained physician who noted on what date he saw Lewis and what treatment he prescribed for him.

Lewis's malarial woes possibly began when serving in the militia in 1795, as evidenced by a letter he wrote to his mother on April 6 of that year in which he told her that he had succumbed to a camp fever. “I have had a pretty severe touch of the disorder which has been so prevalent among the troops.”1 Lewis joined the regular army as an ensign in the Second Sub-Legion on May 1, 1795, and was assigned to Fort Greenville, which was commanded by Gen. Anthony Wayne, overall commander of the US Army at the time. Fort Greenville, located seventy-five miles north of Cincinnati, Ohio, was named for Nathaniel Greene, a personal friend of Wayne and a fellow Revolutionary War officer.

Gen. Wayne won the decisive battle in the Ohio country against the Indians at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794, and a treaty was signed with the various tribes involved at Fort Greenville in August 1795.2 By this time Lewis had chosen the army as his career and was serving with the entry-level officer's rank of ensign. Orderly books show that Lewis would have been exposed to various maladies at Fort Greenville, the most prevalent being malarial fever or “ague.” After the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794, Wayne reported that “the soldiery gets sick very fast with the fever and ague, and have it severly.” The next day he wrote that “the troops were very sickly” and that “the number of our sick increases daily, provision is nearly exhausted.”3

But the summer of 1795 was much worse—especially at Fort Greenville—where hundreds had taken ill.4 The fort was huge, having fifty acres of land within the picket area and a capacity of 4,000.5 On August 9, Gen. Wayne wrote to the secretary of war, “[T]he sickly season has commenced, & we are totally destitute of hospital stores—bark etc. etc.” The “bark” referred to by Gen. Wayne was Peruvian bark, quina in the indigenous language, which was a common treatment for the fever and ague (discussed in greater depth below). Wayne had hoped that the War Department would soon demonstrate “the indispensable Necessity of immediately remedying the deficit” of bark on hand in the fort.6 On September 2, Wayne was most concerned that they had not received any supplies with “the sick list increasing by rapid degrees.”7 In the late summer of 1795, Wayne reported that 120 men were ill in August and 300 in September “and what is truly alarming, there is not nor has there been one ounce of bark in the Medical Stores” for the past six months.8

In desperation, Wayne ordered the removal of the hospital “one mile into the open woods, in a pleasant position.”9 This was a commonly-advised form of treatment for epidemic disease during the period, to take men out of crowded, stuffy hospital rooms and get them into a situation where fresh air could prevent the spread of disease and could help them to recover. Additionally, some physicians believed that fetid, putrid air, like that issuing from a swamp, was somehow the cause of the fever itself. This theory was in dispute during the late 1700s, but was the source of the name of the disease, malaria, from the Italian words for “bad air.” Unfortunately, medical science of the time was not sufficiently advanced to understand that bad air was not a cause, nor fresh air a remedy, for malaria.

On October 5, 1795, Gen. Wayne was at a loss for words when he wrote that they were “totally destitute…of Medicine and Hospital stores.” He had sent men “to Kentucky to procure peruvian bark,” and they were able to obtain twenty pounds.10 One of his officers reported that out of 1,000 troops, 700 had been ill with the ague and fever.11 By early November, 336 were still on the sick list, and by mid-month, medicinal supplies had finally arrived.12

Illnesses at the fort were common, but the ague was a distinctive disease with pronounced features. From the French term fievre aegue, or Latin, febris acuta, the word ague “referred originally to any acute febrile disease and especially a fever accompanied by a shaking or shivering fit.”13 At some point in time, ague and malaria became synonymous.

Malaria was likely introduced into colonial America from Africa by the slave trade.14 It had a complex etiology and was caused by four distinct parasites that were transmitted by mosquitoes. “The fevers caused by these four organisms vary enough in their clinical presentations that different labels evolved for their symptom complexes.”15 The nature of the disease established “long-term chronic infections, in which the host stays infectious to ensure that sufficient transmission…can occur to guarantee survival.”16 Because malaria is not a single disease, it went by a dozen archaic names like “autumnal fever,” “bilious fever,” “remittent fever,” “intermittent fever,” or, simply, “the ague” in various parts of the country.17

By the mid-1750s physicians were writing that the disease was a year-round illness. “From the latter end of January or beginning of February to August, Agues or Intermittents are said to be Vernal; and from August to January or beginning of February, autumnal.”18 Attempting to understand malaria in nineteenth-century America defied medical reasoning because it was episodic or periodic, was not confined in terms of geographic area, was not limited to areas of epidemic concentration (and so did not seem to be spread from one person to another), and was incredibly debilitating and grueling when attacking the patient, but in the intermission of the attack the patient's “memory is almost always impaired or even completely obliterated,” followed by periods in which the patient displays no symptoms at all, only to have renewed attacks months or even years later.19 As delineated at a conference commemorating the three hundredth anniversary of the use of Peruvian bark in 1931, the observable symptoms were laid out in this fashion:

Called ague at a very early period on account of the acute fever, that term soon applied to the more conspicuous feature, the chill, with shaking of the body, in common language ague shakes. Beginning with a feeling of chilliness and with shivering, violent shaking follows. The temperature rises even during the chill, and soon can be felt as a burning heat all over the body, with thirst, nausea, and vomiting, pains in muscles and bones, headache, delirium, and other symptoms. After some hours the fever subsides, followed by profuse perspiration, after which there is a stage of relative well-being, the intermission or remission, according to the degree of freedom from the symptoms.20

That degree of freedom might last a day before the suffering continued, as described in an 1801 medical textbook:

[It] begins with the most intense, painful, and irksome cold, penetrating, as it were, to the very bones. After the first paroxysm, in which there is generally great rigor…sometimes the teeth…by being struck together are knocked out of their sockets. The cold stage can last a great number of hours distressing the patient…then a 5–6 hour head ache.21

Each attack lasted about twenty-four hours and was repeated every day, every third day, or every fifth day for a number of months and then would disappear only to return a few months later as the individual went into a relapse.22 A relapse is defined as a “return of symptoms and signs of a disease after a period of improvement.”23 An attack of malaria was most times left vague with very little description in historic documentation. However, there are personal accounts of malarial sufferers in various populations of the time, and tending to them required intensive care instead of the popular notion of dabbing a cool, wet cloth occasionally on a hot forehead. Malarial symptoms often began with a high fever during which the patient writhed and tossed and had to be restrained by being bound to a bed frame. Soldiers residing in temporary shelters were known to abandon their beds and wander into the fields and swamps and consequently drown.24

The malaria parasite had the capacity to infect all the peoples of the Americas if the mosquito vector was present. In 1793–94, it affected Upper Louisiana where Zenon Trudeau, the Spanish lieutenant governor who resided in Saint Louis, reported that the entire region in the summer months was subject to severe illness due to the fevers and relapses.25 But the fever could strike any time of the year, evidenced by Lewis's bout with it on November 13, 1803, when he said that he was “siezed with a violent ague.”26 This was a familiar pattern, and hundreds of military documents attest to accounts of soldiers and officers who had experienced this radical illness. Capt. Amos Stoddard, the US Army officer who presided over the transfer of the Upper Louisiana Territory to the United States in March 1804, reported that the entire local population suffered from intermittent fever.

The climate in this quarter has frequently been deemed unhealthy. St. Louis is in…lat. 38°, 25°, N.—Strangers from the northern States, (such, for instance, as your humble servant,) are sometimes sickly the first season of their arrival. The usual disorders are of a bilious nature. Intermittents, and fevers and agues, prevail at times—but they readily yield to detergent medicines, succeeded by a few doses of Peruvian bark…. The warm season usually commences about the 10th of July, and ends in September; and during part of this time the mercury generally rises, in the middle of the day, to 94°, and not unfrequently to 108°.27

Stoddard remained in Saint Louis until he led an Indian deputation to Washington in October 1805. About a year later, when stationed in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, he requested a transfer to a post in Tennessee: “It is also very healthy—of such a place I really stand in need, as my frame is still much shattered in consequence of the fever, under which I languished for more than seven months.”28

In 1808, the Arkansas Indian agent John Breck Treat succumbed to malaria:

A few days ago…a sudden and very severe attack of the Fever seiz'd me and although it only remained eight or ten days…I have…constantly…been extremely ill: almost the whole time confined to my bed from which I now write this—from the emaciated, and feeble state I now am in; it is extremely uncertain when I may become convalescent…this is the first month of serious sickness which I have ever experienced.29

The disease was continental and not localized to the east coast and midwestern riverine areas, and was probably carried west over trade routes by early European explorers or by ship-borne traders putting in on the Pacific coast. Chinookan and Kalapuyan peoples in the Willamette Valley suffered with malaria at least by the early nineteenth century.30

It first broke out among the Indians near the fort, and spread far into the country…And with the natives it proved very fatal, sweeping off whole bands, partly probably owing to their plunging into the water when the fever came on constantly.31

They did not understand the illness, and since malaria has its own sweating stage, native logic inferred that “a cure would have been a dip in cold water.”32 Consequently, “maddened by fever, they would rush headlong into the cooling stream…in search of relief” and perish.33

Fur traders in the 1840s were all too familiar with the disease:

[O]ne of my Indians began to show symptoms of the…fever…and the…sick native was obliged to lie down in the bottom of the canoe in great distress. When we reached our evening encampment he was burning with a high fever…. The darkness and damp, chill miasma of the Willamette soon closed over us, and…being unable to endure the pains of fever…[he] crawled to the river's brink and tried to allay the burning inward heat by large draughts from the running stream…in the morning our patient was a picture of disease and distress…by noon…the violence of his pains obliged us to put ashore under the shade of some low willows. In a few minutes violent retchings of the stomach commenced…and in less than an hour he lay stretched upon the grass…a frightful corpse.34

These attacks were typically treated with what Gen. Wayne referred to as the “bark.” Peruvian bark was so named because it was obtained from the bark of several species of the genus Cinchona of the Rubiaceae family that are indigenous to tropical South America. Peruvian bark, also known as Quina was long used by the Quechua Indians of Peru to halt shivering due to low temperatures, and quina-quina indicated “great value,” or medicine of medicines or bark of barks.35 While Cinchona was widely used in England and praised in America as a “sovereign remedy” for the ague, Dr. Samuel Latham Mitchill, a prominent physician, found that “the Peruvian bark was commonly…ineffectual.”36 This was due to three reasons: there were twenty-five distinct species of Cinchona; the content in the bark of the anti-malarial ingredient, quinine, varied in Cinchona trees from 3 percent to 13 percent; and its effectiveness varied between individual trees and different parts of the same tree. The alkaloid, quinine, was isolated from the bark in 1823, and the current treatment for malaria still uses its derivative.37 The grade was established by bark color: red (Cinchona Rubra), yellow (Cinchona Flava), and gray or pale (Cinchona Pallida).38 The highest grade, red, yielded two alkaloids, quinine and cinchonine, while the yellow only produced quinine.39 The Spanish, who cornered the bark market, coveted the highest grade for themselves, casting in doubt the medicinal properties of the fifteen pounds of pulverized Peruvian bark purchased by the Lewis and Clark Expedition.40

For the bark to be utilized, it had to be pulverized into a powder and made into an infusion or decoction, like a tea, but it had its limitations.41 When reduced to a powder, whether it was preserved in a box or in closed vessels, it lost “a great deal of its efficacy,” unless pulverized for immediate use.42 The brewing could take as long as forty-five minutes, and the product was so bitter it had to be mixed in a quart of claret, port wine, or brandy, which the patient drank at regular intervals for a number of days. Cinchona was not regarded as a “specific” for intermittent or other fevers because the accepted practice of the time revolved around the Greek doctrine that “perceptible evacuation was essential to cure and that a drug ingested as hot tea was counterindicated in a fever.”43 Unfortunately, by the time this treatment began to have some effect, the attack had probably run its course. Continued heavy use could produce serious side effects, including tinnitus (ringing in the ears) and deafness.44

The bark was not the only remedy for malaria, as many physicians of the time prescribed calomel, the powdered form of mercury. Dr. Benjamin Rush, one of Thomas Jefferson's medical advisors, relied on calomel exclusively as treatment for malaria and dispensed his own formula, a combination of mercury and jalap, a strong purgative, which came to be known as “Rush's pills.”45 In preparation for the expedition, Lewis consulted Dr. Rush about his illness in May of 1803. Rush specifically wrote: “Directions for Mr. Lewis for the preservation of his health & of those of who were to accompany him,” and forwarded those instructions to Jefferson.46 Rush believed solely in “heroic” medicine and prescribed his own mercury pills to Lewis—and the expedition bought “50 doz. Bilious Pills to Order of B. Rush,” which were taken for all sorts of ills.47 Dr. Rush believed that Lewis suffered from a recurring bilious fever, another name for the ague, but a fever that presented with a malarial character. Lewis dutifully adhered to Rush's prescription, but over the years modified the formula and noted it in his account book:

Method of treating bilious fever when unattented by Typhus or nervous symptoms—Let the patient take a strong puke of tartar emetic: the second day after a purge of Calomel and Jallop, which should be repeated after two days more, to be taken in the morning, and no cold water to be used that day.—a pill of opium and tartar to be taken every night and after the purgatives. ten grains of Rhubard [rhubarb] and 20 grains of Barks should be repeated every morning and at 12 O'clock.48

The most telling feature of this description is the length of time that he devoted to the treatment, and conversely how long the bout affected him. Another name for this disorder was bilious cholic, which could produce “excruciating pain,” and often “relaps'd with such violence” that as one observer remarked “baffled the powers of medicine.”49

There has been a tremendous amount of curiousity expended on why Lewis chose Clark to be coleader of the expedition. It is possible that their original bond was formed as a result of the illness at Greenville in the summer of 1795. On September 10, Clark departed Greenville on a special assignment, ending the period during which Lewis and Clark originally served together in the army, making it most probable that Lewis and Clark began their friendship between May 1 and September 9 of 1795.50 In August, Gen. Wayne reported that 120 soldiers were sick with malaria at Fort Greenville. That was cause for great alarm because the medical staff, comprised of one surgeon and four surgeon's mates, was wholly insufficient to care for the multitude of sick.51 Other soldiers and officers were employed to carry out the menial duties, and without hospital stores, one can only imagine the desperate situation confronting Gen. Wayne.

Sickness consumed vast amounts of energy from both the ill as well as the healthy in the form of caretaking. It is quite possible that either Lewis or Clark or both were taken ill during this period, or one or both might have assisted with the care of patients. Being expert marksmen was the catalyst that brought the two together, but illness, and its caretaking counterpart, may have clinched the friendship. By May 1803, Lewis chose Clark as the expedition's cocommander, and upon receiving Lewis's moving invitation, Clark gladly accepted:

My friend I join you with hand & Heart and anticipate advantages which will certainly derive from the accomplishment of so vast, Hazidous and fatiguing enter-prize. You as doub[t] will inform the president of my determination to join you in an “official Character” as mentioned in your letter.52

Lewis and Clark were adept at caring for both their men and Native Americans on the expedition and were given the appellation “Captain—Physicians” by modern medical doctor—historians.53

The evidence is overwhelming that malaria was a prevalent and formidable disease in seventeenth-and eighteenth-century America. Although historians agree that Lewis became infected with malaria at some point in his life, they dismiss its relevance to the expedition and to his later duties as governor of the Louisiana Territory and author of a published form of the expedition journals. What they failed to appreciate was that once Lewis had contracted malaria, he had it for the rest of his life—it was incurable and untreatable during his lifetime.

As stated in the biography Meriwether Lewis, “Malaria is a disease fitted with a hydra-head of painful secondary complications that mimic other conditions like anemia, jaundice, migraine-type headaches, and enlarged liver and spleen.”54 During March 1807, several persons visiting Thomas Jefferson, including Jefferson and Lewis, became ill with a bout of malaria. Historians have characterized this example as a humorous situation where everyone in the presidential mansion caught a cold, but what this really demonstrates is that malaria can imitate many diseases and fool even the most hardened experts.55 Several persons residing with President Jefferson jointly experienced what is called today a synchronous malarial attack. Malaria can strike in the middle of winter as easily as in the summer months because the parasite depends upon the host's circadian rhythm, which signals the opportune time to proliferate.56

On March 2, President Jefferson reported that his son-in-law, Thomas Mann Randolph Jr., had succumbed to a “chill and fever,” which lasted four days, and Lewis and others attended to the stricken man. On March 6, Jefferson remarked that he had caught a very bad cold, and On March 11, Lewis wrote that he had been indisposed and took some of Rush's pills.57 This prompted historians to conclude that everyone at Jefferson's mansion had caught his cold.58

The illness that affected several persons at the same time was a classic presentation of the ague. Jefferson complained of a periodical headache, which was his way of explaining the agues in the head that are also described today as a retroorbital headache—a sharp pain behind the eye.59 Medical historians believe that his periodical headache was a migraine; however, Daniel Drake, one of the foremost physicians of the upper Mississippi Valley, recognized that the periodical headache was a symptom of the ague.60 Jefferson suffered from relentless headaches, what he “called the Sun-pain,” beginning in 1764, and by 1807, they had become a familiar and debilitating malady.61 Little documentation exists about Lewis's malarial bout, but it disabled him until the beginning of April, when he departed Washington for Philadelphia. Jefferson, on the other hand, was very ill too and wrote how those headaches crippled him. He relied upon the most advanced treatments of the day, using bark and calomel, hallmark remedies for this type of condition.62 Jefferson was so ill from these frequent malarial attacks that he departed the capital for Monticello to recuperate. It was the third week of May 1807 before Jefferson had recovered; he had actually been sick for almost three months.63

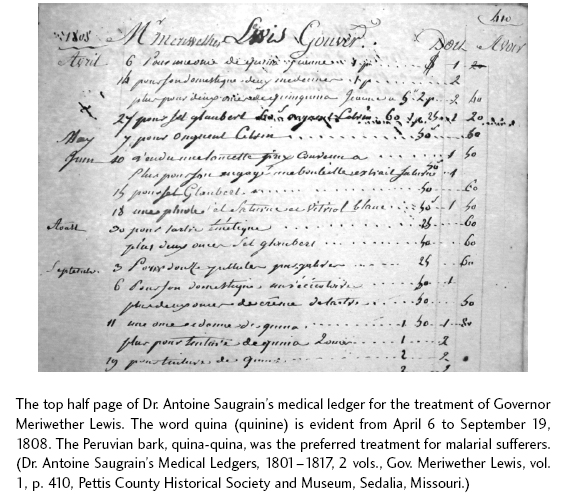

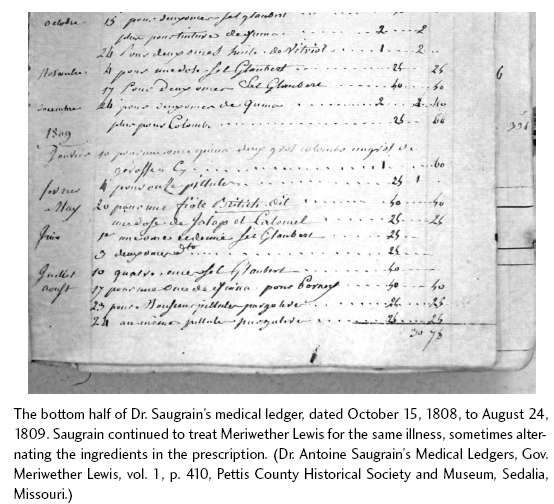

Like Jefferson, Lewis continued to seek medical treatment for malaria. When Lewis arrived in Saint Louis on March 8, 1808, to take up his duties as governor, he met with Dr. Antoine Saugrain, a physician and chemist, who began treating him for the disease less than a month later.64

Born in Paris, France, Dr. Saugrain began practicing medicine in 1783, and by 1799 he had arrived in Saint Louis and opened a practice. In 1805, he was appointed surgeon's mate at Fort Bellefontaine, and four years he later became surgeon at the fort. It is noteworthy that in 1809 he was also the first physician west of the Mississippi River to use the Jenner cowpox vaccine to prevent smallpox.65

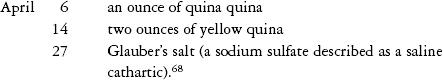

Beginning April 6, 1808, the illness that plagued Lewis since writing to his mother on April 6, 1795, sporadically returned, culminating in a steep descent into a series of drastic prescriptions that allows us to see, for the first time, Lewis's physical debility. Thirteen years to the day that he informed his mother of a bout with camp or putrid fever, Lewis met with Dr. Antoine Saugrain, and judging from the entries in Dr. Saugrain's medical ledgers, the governor was very ill.66 On April 6, Saugrain gave Lewis an ounce of quina quina.67 For the entire month, Lewis battled malaria:

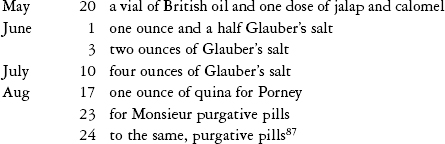

Lewis was illness-free for the next six weeks, although on June 15 he received a dose of Glauber's salt and on June 18 a vial of “saturne white vitriol,” which was a by-product of sulfuric acid, a substance to “check diarrhea.”69 For almost two months following, Lewis was healthy again, until August 30, when Saugrain gave him tartar emetic and two ounces of Glauber salts: it is evident that Lewis had already been ill for a time.70 Tartar emetic, a combination of antimony and potassium dissolved in water with Glauber's salts, was “an all-purpose depletive,” which in “small amounts…produced disabling vomiting.”71 This therapy regimen of purging the digestive tract was thought at the time to alleviate the symptoms of malaria, but of course it only made Lewis more sick.

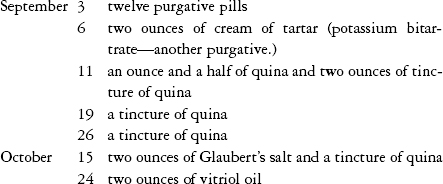

The entire month of September 1808, which mirrored the physical distress to Lewis caused by the same disease a year later, demonstrated (through entries in Dr. Saugrain's ledger) the episodic nature of malaria:72

In Lewis's account book, he kept several formulas, one of which he labeled the “best stomachic,”73 which was a specific for malaria: “1/4 oz of cloves, 1/4 oz of Columbo, 1 oz Peruvian bark, 1 quart of port wine—the ingredients to be well pounded and shook when taken—a wine glass twise or twise a day may be taken with good effect, it is an excellent restorative.”74

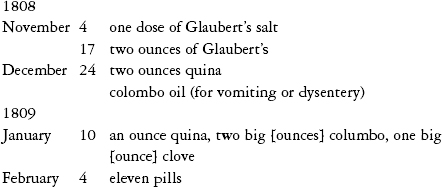

Lewis wrote to his mother on December 1, 1808, stating that he generally shared good health.75 He also wrote a voluminous letter to President Jefferson on December 15 detailing a number of events from the time of his arrival in Saint Louis to the signing of the Osage Treaty on November 10, 1808.76 For the remainder of 1808 and into early 1809, Dr. Saugrain's ledger contained a repeat of the same prescriptions:

For about two months, Lewis enjoyed good health and finalized plans for the Missouri Fur Company to return the Mandan chief Sheheke-shote and his family after two long years in Saint Louis. On May 20, Dr. Saugrain gave Lewis a vial of British oil and one dose of calomel and jalap. British oil and jalap were unsavory substances—the first was a combination of the oils of turpentine, linseed, amber, juniper, and petroleum, while the other was a Mexican root and “drastic cathartic” that caused violent intestinal cramping. Calomel and jalap were used together to evacuate the mercury as fast as possible.77 Up until this time, Lewis had been taking quina quina, his preferred treatment, but Saugrain switched Lewis to a more powerful alternative. This dosage was a poisonous cathartic and the same treatment that Dr. Rush prescribed for malaria and almost everything else.

At the end of May, Dr. Saugrain was appointed surgeon of Fort Bellefontaine and required to make a report on current conditions there, which he described as dismal: “Intermittants are very prevalent in all Seasons of the Year…but they leave the Patient in a state of debility…. Putrid fevers cause great debility towards the end and have been mortal in several cases.”78

It was specifically his understanding of the air and damps, in the form of effluvia or miasma—bad air, that led him to describe how the illness pervaded the air and released “noxious…exhalations” near Bellefontaine:

The Cantonment [fort] is situated on a low, flat and Morassy bottom…after a Rain the Water having no issue, becomes stagnant, which, together with a neighboring Creek, which is dry during the Summer, occasions noxious and foeted [fetid] Exhalations, injurious to health: as a proof of the insalubrity of the Air of this place, after a Considerable rain, the Sick reports are generally double and often treble.79

Saugrain was all too familiar with the summer conditions in the Louisiana Territory, which coincided with Lewis's continued bout with malaria and sick soldiers at the fort and in the surrounding area.80

Lewis attempted to write to the secretary of war on July 8, but writing proved to be difficult.81 Malarial sufferers struggled when writing letters and some took months before they could competently hold a quill. An account written by a traveler to a friend in Saint Louis described his frustration after succumbing to malaria, from which it took weeks to regain some strength. He wrote an almost unreadable letter, to which he alluded, saying, “you will Discover by the shaking of my hand.”82 Interestingly, on August 18, Lewis received a stinging rebuke from the accountant of the War Department, rejecting payment of a draft he had submitted.83 On that day, shocked beyond description, Lewis did not pen the most important letter of his life—someone else wrote it for him because he was probably in the throes of an ongoing malarial relapse. “Yours of the 15 th July is now before me, the feelings it excites are truly painful. With respect to every public expenditure, I have always accompanied my Draft by letters of advice, stating explicitly, the object of the expenditure….”84

About a week later, on August 24, Lewis paid Saugrain for purgative pills and to assemble a medicine chest for his voyage down the Mississippi River to New Orleans.85 This was the trip that Lewis had been planning for a year, to return to Philadelphia and work on the publication of the expedition journals.

Governor Lewis was by no means the only person in Saint Louis who was ill with malaria—the month of August proved to be sickly for many Saint Louis residents, including most of Lewis's friends.86 This timeline continues to demonstrate Lewis's illness in the summer of 1809:

Judging from these dates, it is clear that Lewis preferred quina quina to ingesting calomel, and the argument that Lewis suffered from mercury poisoning has been greatly overstated. Lewis preferred Peruvian bark, then Glauber's salts, and rarely, calomel, to treat his malarial symptoms.88

On September 4, 1809, Lewis departed Saint Louis by boat. His intention was to travel to New Orleans and take a seafaring boat around Florida and then sail up the east coast of the United States to Washington. Upon his arrival eleven days later at Fort Pickering, in present-day Memphis, Tennessee, Lewis had succumbed to a malarial relapse. The boat crew informed Capt. Gilbert Russell, the commander of Fort Pickering, that Lewis had made two attempts to kill himself during the trip and that upon his arrival he was mentally deranged.89 Capt. Russell assisted Lewis up the 120 square-log steps to the fort and put him in his own quarters.

Capt. Russell had first arrived at Fort Pickering on June 9, 1809, and had reported that the fort “was in the most wretched state.” Russell summarized the work to be performed from repairing the pickets, the roofs of the officer's quarters, and the huts for the men to replacing rotted floors and building a chimney. By August 26, none of the repair work had been accomplished because his company had been stricken with malaria: “And such has been the unhealthiness of the season that with the Troops I have as yet been able to make no improvement to Fort Pickering—Out of forty eight Officers & men I have sometimes had but eight or nine fit for duty.”90

Other distressing news followed him when he reported that “four of my best Mechanics” were drown'd a few days ago…. My only two Brick layers were drown'd” too.91 The cause of their drowning could have easily been related to malaria. William C. Smith, the surgeon of the garrison, mirrored Russell's complaints and reported that from the time of Russell's arrival at the fort “sickness had immediately prevail'd here in an uncommon manner.” Regardless of his duties, Smith was stricken for five months and “in that time frequently prescribing for the sick, when confined on my bed.” He recovered the first week of November but felt that his health was permanently damaged “probably forever…under the most obstinate and confirmed complaint of my liver.”92

Under appalling circumstances, Lewis arrived “to this sequestered and sickly Post.”93 Without skilled workmen or cash, Russell's own quarters were completely dilapidated, and even though he invited the ailing Lewis to recuperate in them, who can imagine their condition? This was the frontier, and rudimentary conditions were the norm, as evidenced by Russell's ending paragraph to the secretary of war: “Unless the Garrison is repair'd before the hard weather commences, which can not be done without a considerable sum of money in its present state the Troops would all die.”94 Conditions were just as unfavorable in Saint Louis at Fort Bellefontaine, but with Dr. Saugrain as surgeon's mate, an expert was at the helm who had seen many diseases and assorted ills on the frontier.

With the discovery of Antoine Saugrain's medical ledgers, a new understanding has emerged about Meriwether Lewis and the frontier life that surrounded him. The prevailing thought concerning Lewis's illness has always been that it was mental in origin, while today, medical testimony from 1809 proves the opposite. Lewis suffered from a physical disease, which tormented him for his entire adult life.