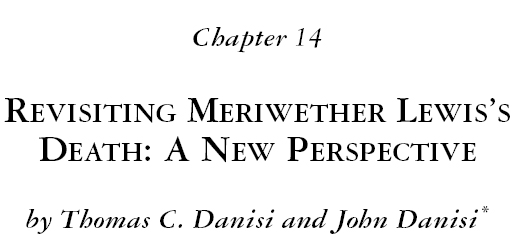

One of the great American historical mysteries concerns the death of Meriwether Lewis (1774–1809). Did he commit suicide? In the past fifty years, the discovery of letters written at the time of the explorer's last days indicate that he was subject to depression, to bouts of alcoholism, and to mental derangement. Although the prevailing view supports the reasoning that depression drove him to suicide, we believe through studying new finds that Meriwether Lewis, in his adult life, suffered from chronic, severe, and untreated malaria, an incurable disease at that time. In light of this new information, Meriwether Lewis was not stricken with a psychological illness, namely, depression, but rather with a physiological disease, “the ague,” which is known today as malaria.1 A study of Lewis's malaria and the symptoms it produced provides the gateway toward a better understanding of the nature of his death.

HYPOCHONDRIA TIED TO A DEPRESSIVE STATE OF MIND:

EXTREME DEPRESSION MADE LEWIS KILL HIMSELF

Most historians have concluded that Lewis's illness was psychological and that he suffered from lifelong depression. They have repeatedly claimed that a pattern of behavior had developed during his life that was consistent with someone who suffered from a mental condition. Historians have arrived at this conclusion based mainly on Thomas Jefferson's testimony, but also from other persons who knew Lewis. Evidence left behind by Lewis's contemporaries described events leading up to his death and discussed his death after the fact in terms of what were perceived as signs and portents that foreshadowed his demise. Lewis's contemporaries have been placed by historians in an order based on the importance of their connection to him and their perceived veracity based on class and position in society: President Thomas Jefferson, William Clark, Capt. Gilbert Russell, Maj. James Neelly, John Pernier, and Priscilla Grinder.

When Thomas Jefferson's election to the presidency of the United States was determined by the Electoral College in February 1801, he hired Meriwether Lewis as his private secretary. In 1803, Jefferson appointed Lewis as the leader of the famous Lewis and Clark Expedition, and then four years later, as governor of the Louisiana Territory.2 William Clark accompanied Meriwether Lewis on the Lewis and Clark Expedition as cocommander and also resided in Saint Louis as Indian agent of the Louisiana Territory during the same timeframe that Meriwether Lewis was governor.3 Capt. Gilbert Russell, commander of Fort Pickering, cared for Lewis in the last two weeks of September 1809.4

Thomas Jefferson, in 1813, wrote the most definitive view of Lewis's death in a biographical letter for the introduction to the Lewis and Clark Expedition Journals. Jefferson knew Lewis's family well, having lived near them in Charlottesville, Virginia. In this letter Jefferson outlined the most damning evidence about Lewis's illness, which has led most historians to conclude that Lewis committed suicide.5

Governor Lewis had from early life been subject to hypocondriac affections. It was a constitutional disposition in all of the nearer branches of the family of his name…. While he lived with me in Washington, I observed at times sensible depressions of mind.6

Jefferson also repeated his view to Capt. Gilbert Russell:

We have all to lament that a fame so dearly earned was clouded finally by such an act of desperation. He was much afflicted & habitually so with hypocondria.7

Jefferson's explanation of Lewis's illness was the result of a series of events that culminated in Lewis's unexpected death. On September 4, 1809, Lewis departed Saint Louis on a boat bound for New Orleans, which would take him to Washington.8 A week later he disembarked at New Madrid with his servant, John Pernier, and went to the New Madrid Courthouse to make out a will.9 Four days later, on September 15, he arrived at Fort Pickering, the site of present-day Memphis, Tennessee. Capt. Gilbert Russell reported that the boat crew informed him that Lewis had made two attempts to kill himself—and in one of them he nearly succeeded. As Russell assisted Lewis up to the fort, he commented that Lewis was in a state of mental derangement.10 Lewis remained at the fort for about two weeks, recovering his health.

On September 29, Maj. James Neelly, the Chickasaw Indian agent, departed Fort Pickering to escort Lewis to Nashville. Neelly noted less than a week into their trip “that [Lewis] appeared at times deranged in mind.” They rested two days, then two horses strayed from camp and Neelly went looking for them the morning that Lewis, Pernier, and the packer continued on to a small wayside inn known as Grinder's Stand.11 When they arrived at Grinder's Stand on the evening of October 10, Neelly had still not rejoined them. That evening Priscilla Grinder made dinner and reported that when she served the food Lewis “walked backward and forward before the door talking to himself.”12 Afterward, Lewis went to his room, Priscilla and her children to hers, and Pernier and the packer to the stable. Before Neelly's arrival the next morning, Lewis had died from gunshot wounds. 13

When Maj. Neelly arrived at Grinder's Stand on the morning of October 11, he prepared Lewis's body and then buried him, afterward questioning Priscilla Grinder and Pernier. He then took Lewis's belongings to Nashville, arriving about October 18, and sent a long letter to Thomas Jefferson detailing the trip from Fort Pickering. The letter began with very distressing news:

It is with extreme pain that I have to inform you of the death of His Excellency Meriwether Lewis, Governor of upper Louisiana who died on the morning of the 11th Instant and I am sorry to say by Suicide.14

William Clark, who had been traveling eastward, had the news broken to him in a brutally unfair way: by reading a newspaper account. Immediately afterward he penned his reaction to Lewis's sudden and unexpected death in a letter to an extremely trusted correspondent, his older brother Jonathan Clark, stating that “I fear O! I fear the waight of his mind has over come him, what will be the Consequence?”15

Most historians have claimed that it was depression that brought about his death—that is, by suicide.16 Three historians who have written on Lewis and Clark, Gary Moulton, Stephen Ambrose, and Dr. David Peck, believed that depression caused Lewis's death.

Moulton believed in a strict analysis of Jefferson's statement that Lewis was subject to hypochondriac affections and “that he suffered bouts of depression," which resulted in a “state of severe depression” when he departed Saint Louis.17

Ambrose's approach was direct and unwavering: that Lewis's sensible depressions of mind equated to “the same melancholy in Lewis's father, and…a malady that ran in the family.” He further wrote that his depression was exacerbated by drinking to excess and “suffering from a manic-depressive psychosis.”18

Peck sided with what he perceived to be Jefferson's viewpoint, that “Lewis had a constitutional/genetic tendency toward depression, which was beyond his conscious control.”19

Traditional historians such as Dawson Phelps, Paul Russell Cutright, and Donald Jackson have concluded that Meriwether Lewis suffered from depression in its various forms. Dawson Phelps, the most outspoken of the group and a National Park Service historian, stated flatly in 1956 that Lewis killed himself. Phelps based this statement on Lewis's troubled governorship, noting that he was beset with financial woes and agreeing with Jefferson's observation that Lewis “suffered from sensible depressions of mind.” Phelps ended his paper with a judgment that still resounds today: “In the absence of direct and pertinent contemporary evidence to the contrary, of which not a scintilla exists, the verdict of suicide must stand.”20

Paul Russell Cutright believed that Lewis was unstable and based his conclusion on four factors: his failure to find a wife; his intemperance; his delay in furnishing a manuscript copy to publisher Conrad; and the erosion of his long-standing relationship with Jefferson.21

Besides depression as the cause of his suicide, there is also the additional claim that Lewis was an alcoholic. Donald Jackson, editor of Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, agreed with Phelps, “I am inclined to believe that Lewis died by his own hand,” but attributed the act to Lewis's “lapse into intemperance.”22 At the time, Jackson had found a letter that Capt. Gilbert Russell had written to Thomas Jefferson describing this new aspect:

The fact is…his untimely death may be attributed solely to the free use he made of liquor which he acknowledged verry candidly after he recovered & expressed a firm determination never to drink any more spirits or use snuff again both of which I deprived him of for several days & confined him to claret & a little white wine.23

Jackson also confirmed his hypothesis by citing Jefferson's reply to Russell:

[H]e was much afflicted and habitually so with hypocondria. this was probably increased by the habit into which he had fallen & the painful reflections that would necessarily produce in a mind like this.24

According to Jackson, the word “habit” confirmed that Lewis suffered from alcoholic depression and that it eventually led to his suicide.25 True enough, Jefferson used the word “habit,” but Jefferson was not using the word to refer to alcoholism, but to hypochondria. Clay Jenkinson connected Lewis's inherited disposition to a “man afflicted with bipolar personality disorder,” which “points to melancholia, alcoholism, and suicide” as the likely causes of death.26 Another historian who is also a medical doctor, Ronald Loge, refuted the hypothesis that Lewis suffered from malaria, and instead, relied upon a strict medical and evidentiary standpoint that “historical retrospective or forensic analysis is unable to demonstrate this.”27

Other peripheral views concerning Lewis's death are interesting but speculative. Some do not mirror Jefferson's statement but instead concentrate on the events at Grinder's Stand or dismiss facts regarding Lewis's personal history. For instance, Dr. Reimert Ravenolt, an epidemiologist, declared that Lewis had contracted syphilis from relations with Indian women on the expedition and probably died from it years after infection. Ravenholt believed that the escapade occurred on August 13 and 14, 1805, but Lewis had written statements to the contrary.28 “I think its most disgusting thing I ever beheld is these dirty naked wenches.” Lewis's knowledge of the effects of venereal disease was abundantly described throughout the journals: “once this disorder is contracted it…always ends up in [decrepitude], death, premature old age.” 29 Since Lewis was responsible for the health of his men, and as an officer of the army was sworn to observe protocols through personal example; and since he announced in general orders that his men should refrain from liaisons with native women for the sake of their health and the success of the expedition; and since he personally treated those with the disease, seeing firsthand the aftereffects, it seems doubtful that he indulged in this sort of dalliance.

Another novel theory attempted to discredit Priscilla Grinder and Pernier by suggesting that the night of Lewis's death was moonless, and thus, whatever the two thought they saw, they couldn't have.30 The theory dismisses the science of photometry, implying that it had no bearing on the night in question—that these two persons living during this time period and in the wilderness could not acclimate their sight to darkness. Photometry textbooks clearly state that a person's eyes will adjust to darkness when leaving an area of bright light (not candle or firelight, which is not bright enough) after twenty minutes.31

There are theories suggesting that Lewis was assassinated by thugs at Grinder's Stand or by minions sent by the nefarious Gen. James Wilkinson. Nameless thugs have always been an interesting story line, but with no foundation, and the feeble attempt to tie Wilkinson to the plot is even weaker because he was stationed more than five hundred miles from Fort Pickering.

Other theories came from the psychiatric sector: Howard Kushner embraced Jefferson's description of Lewis's constitutional disposition. He argued that Lewis's father's death invoked “incomplete mourning,” where Lewis played catch-up to his “repressed loss,” which corroborated the predictable suicide.32

Kay Jamison, on the other hand, remained within the bounds of the historian's perspective and took Lewis's own grasp of wonder or lack thereof, postexpedition, to say that “the same bold, restless temperament that Jefferson saw in…Lewis can lie uneasily just this side of a restless, deadly despair.”33 If these two positions were really true, Lewis would never have risen from his bed and explored the continent.

Finally, historian Ann Rogers disagreed with the evidence presented in the biography Meriwether Lewis that argued that Jefferson's description of hypochondria was a description of a physical disorder. She countered that it was “an outlook, a disposition, a state of mind.”34 Rogers quoted various letters that Jefferson wrote from 1787–1816 using the word hypochondria and maintained Jefferson was referring to temperament and “not diagnosing any physical disease.”35 What she failed to acknowledge is that the eighteenth-century word hypochondria did not carry the same definition in modern usage, which she has misinterpreted to be the same. The eighteenth-century word pertains to a physiological complex while the modern term stipulates a mental state where the patient is continually anxious about an unreal physical condition.36

HYPOCHONDRIA TIED TO A PHYSICAL DISORDER:

THE AGUE (MALARIA) MADE LEWIS SHOOT HIMSELF

Let us return to Jefferson's statement about Meriwether Lewis's condition. It is important to do so because Jefferson was intimately acquainted and involved with Lewis's life and because Jefferson's statement has been used to establish the nature of Lewis's death.37 Jefferson wrote:

Governor Lewis had from early life been subject to hypocondriac affections. It was a constitutional disposition in all of the nearer branches of the family of his name…. While he lived with me in Washington, I observed at times sensible depressions of mind.38

Two questions arise here: What did Jefferson mean in writing that Lewis was afflicted with hypochondria? And secondly, what did Jefferson mean when he said that Lewis's hypochondria had a constitutional source? Surprisingly, the historians mentioned earlier seem to speak about the first question, but they fail to address the second question in an adequate or complete way.

Lewis's “hypocondriac affections” are not to be understood as having a genetic or a psychical source, but, in Jefferson's phrase, a “constitutional source”; that is, an organic or bodily source passed on to Lewis by his family in the form of a “diseased body.” As so understood, Lewis's hypochondriac affections, his “sensible depressions of mind,” are byproducts, or afflictions, arising from the diseased organs in Lewis's body, notably, the diseased organs in the hypochondriac, or abdominal, region of Lewis's body. And Jefferson also notes that Lewis's body, in its diseased state, has its roots ultimately in his father: “It was a constitutional disposition in all of the nearer branches of the family of his name, and was more immediately inherited by him from his father.”

Jefferson remarks about the intimate relation between the hypochondriac mind and the diseased body. He writes, “There are indeed (who might say Nay) gloomy and hypochondriac minds, inhabitants of diseased bodies, disgusted with the present, and despairing of the future; always counting that the worst will happen, because it may happen.”39 Jefferson's statement is crucial to understanding the nature of hypochondria, which is linked to a bodily disposition or bodily makeup. It follows that we must connect Lewis's hypochondria with Lewis's constitutional makeup, that is, his bodily makeup or disposition, if we are going to understand the full significance of Jefferson's statement.

It is important to note that Jefferson's acquaintance with the word “hypochondria” is not rooted in the modern science of psychology—indeed, it is not rooted in psychology at all. It has its roots in his knowledge of the languages of Greek and Latin, which he studied and mastered. As is well-known and documented, Jefferson was a lifelong student of the Greek language.40 In 1800 he reminded us that “to read the Latin & Greek authors in their original, is a sublime luxury.…I thank on my knees, him who directed my early education, for having put into my possession this rich source of delight.” Almost twenty years later, he reiterated his deep passion for reading Greek texts in their original state: “The utilities we derive from the remains of the Greek and Latin languages are…models of pure taste in writing…. Among the values of classical learning, I estimate the luxury of reading the Greek and Roman authors in all the beauties of their originals.”41

When Jefferson wrote about “hypochondriac affections,” and “hypochondria,” we have to assume that he was referring to an organic, or, a bodily condition. But the question arises: What do the languages of ancient Greek and Latin tell us? The word “hypochondriac” comes from the Greek—hypochondriakos—and from the Latin—hypochondriacus—meaning “of the abdomen” and in the singular form, “hypochondria” or the abdominal region of the body. Jefferson's statement that Lewis was afflicted with hypochondriac affections means he was affected by and concerned with that region of the body. Hypochondriac affections actually referred to the disease, which is hypochondria of pathological proportions, “a complex physical sickness,” and that the “hypochondriasis [or hypochondria] that afflicted Lewis was a debilitating complication of chronic untreated malarial fever.”42 In short, Jefferson is informing us that Lewis's concern has to do not only with the abdominal region of his body but also with a disease inhabiting his body.

Jefferson's description of Lewis's hypochondria points to a complex condition, and the root cause of his illness originated from a physiological disease. This syndrome needs to be examined in some detail in order to understand the depth of its meaning. In the usage of the time, hypochondria described a set of physical symptoms. The first part of the word, hypo, means “under” and chondros means “cartilage,” and the compound word referred to the area immediately below the ribs. The anatomical region below the ribs and above the pelvis, called the hypochondrium, included the cartilage, viscera, muscles, and organs located there. When ailments were ascribed to the hypochondrium, the physical illness was known as hypochondriasis.43

When Jefferson stated that Lewis suffered from hypochondriac affections, he was referring to a physical locality, the abdominal area or the hypochondriac region of the body. An 1841 medical dictionary explained it in this way:

The seat of the hypochondriac affections is in the stomach and the bowels…. On dissection of the hypochondriacal persons, some of the abdominal viscera (particularly the liver and spleen) are usually found considerably enlarged.44

Thus, the hypochondriac region was comprised of some of the major organs in the body that processed blood and filtered toxins: the spleen and the liver. It also included the digestive system, the stomach, and the intestines. As late as 1850, physicians were still calling the abdominal area the hypochondriac region.45

In the literature of the time, the hypochondriac region was commonly associated with a lexicon of phrases, including vapours and spleen, which ultimately evolved into the more recognized term splenic humors. Meriwether Lewis included the term spleen in his 1795 court-martial trial: “[T]he records of this noble Tribunal…ought to be held sacred to honor and justice among military men, should not be disgraced with charges fostered by malice and dictated by spleen.”46

The term “dictated by spleen” was associated with physiological pain and covered a variety of ailments like malaise, pain, temper, and disgust, as did the highly emotive, “vents his spleen,” or “the spleen of the satirist,” or “be thou my shelter from the spleen of vexatious housewives,” to the more nasty “a farrago of miserable spleen,” or the highly poignant, “his antagonists…are not real characters, but the mere drivelling effusions of his spleen and malice.”47 Hypochondriac affections and spleen coexisted together in a time when this sickness was thought to dwell in this bodily region.

One physical disorder that enlarged the spleen and liver was known as the ague. The ague was also tied to physical symptoms known as hypochondriac affections. Some historians have argued that the ague and malaria were unrelated, but today, malariologists have agreed that the two conditions were one and the same, namely, the ague was malaria.48

The ague was the name of an old disease, but in the late eighteenth century it was a fever accompanied by a shaking or shivering fit.49 When persons succumbed to this illness, they referred to it as “ague and fever.”50 Sometimes they only mentioned the ague, and for good reason: it attacked them incessantly for a period of weeks to months and impaired their thinking.51 At some point in time, ague and malaria became synonymous. The Greeks knew it as intermittent fever, and its familiar presentation began with a fever, skull-splitting headaches, intense chills, and prodigious sweating. The attack usually lasted twelve to eighteen hours, and a period of convalescence followed, during which it could take days for the patient to fully recover unless the sufferer experienced another attack, which could occur every day or every third day for a period of months.52

Malaria was known by a dozen archaic names like autumnal fever, bilious fever, remittent fever, intermittent fever, bilious remittent fever, the chills and fever, or, simply, the ague. Those names were used in different parts of the country because malaria is not a single disease but a family of four different diseases caused by four different parasites.53

The malarial parasites are microscopic and live in the gut of a mosquito. The bite or sting of the mosquito transmits the parasites into the bloodstream, which then make their way to the liver. The parasites may remain dormant for a time or morph into several stages of maturity until they burst out of the liver in great numbers and invade the red blood cells for nourishment, which triggers the body's defense mechanism to switch on, resulting in the characteristic stages of fever, chills, and sweating.

Once the disease becomes chronic, a reduction of red blood cells is common, which puts a great strain on the spleen, causing it to enlarge.54 A healthy spleen weighs barely five ounces, but after repeated malarial attacks, the spleen can occupy the entire abdominal cavity and weigh up to ten pounds. The enlargement of that organ has been characterized by patients as a dragging pain in the abdomen.55

Untreated malaria can lead to unpredictable, wild, and erratic behavior and has been cited by physicians during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as well as today. When Lewis arrived at Fort Pickering, Capt. Gilbert Russell reported that he was in a state of mental derangement. Dr. Jean Alibert remarked:

Every paroxysm of [intermittent] fever…was evidently marked by a derangement of intellectual functions…. The delirium continued the whole day…the patient awoke…spoke rationally for a few minutes, but soon relapsed again into such a deep delirium that he could scarcely be kept in bed.56

Alibert was confirming that the patient he was treating was being restrained. A more alarming reason for the restraint was to prevent a patient from committing bodily harm, a factor that English physician John Pringle noted when describing soldiers who had succumbed to the first stage of the ague.

There were some instances of the head being so suddenly and violently affected, that without any previous complaint the men ran about in a wild manner, and were believed to be mad, till the solution of the fit by a sweat, and its periodic returns, discovered the true nature of their delirium.57

Pringle, a military camp physician for twenty-five years, may not have known the modern term for malaria, but he knew the sequence:

That a few returns of the paroxysms reduced their strongest men to so low a condition as to disable them from standing. That some became at once delirious…and would have thrown themselves out of the window, or into the water, if not prevented.58

Aboard the boat, Lewis's irrational behavior had to be restrained, and there is evidence from the modern day to support this claim. In 1995, a New York Times writer traveling in Uganda succumbed to a malarial fever and “a friend had to throw himself across my body to keep me from shaking myself off the bed.”59

Priscilla Grinder reported that after Lewis had retired to his room at Grinder's Stand, she was suddenly awakened in the early morning by the sound of gunshots.

In 1828, Dr. John Macculloch, another English physician tending to chronic and uncured ague patients, wrote about their irrational thinking:

The patient feels a species of antipathy against some peculiar part of his body…or he longs to commit the act by wounding that particular point…this very point is the one eternally forcing itself on his imagination as an object of hatred and revenge. And so perfectly insane is this feeling, that I have been informed by more than one patient…that there is no conviction…that death would follow; or rather the impression is…if the offending part could be exterminated or cured by the injury…that the patient would then be well.60

Lewis's actions in his final hours are consistent with Macculloch's observations:

There is also a particular part of the body affected by an uneasy but undefinable sensation, such that the mind constantly reverts to it as a source of suffering…or a condition of absolute pain…always returning to that one point under the same stage of the fever or delirium. When, as is not unusual, it is seated in the head, it is even distinguishable by a dull pain, or a confusion, or a sense of “buzzing” (for it is described by patients) in one fixed place.…I have the assurance of such patients, that the suicidal desire is exclusively directed to that spot, and that while a pistol would be the only acceptable mode, there would also be no satisfaction unless that were directed to this actual and only point.61

The unsystematic courses of action employed by malarial sufferers were extreme efforts to allay pain, even if it meant to wound themselves in the head.62

These examples mirror Meriwether Lewis's final days. His affliction was real, it was located in the hypochondrium, and he had sought counsel from Doctors Benjamin Rush and Antoine Saugrain.63

In May 1803, prior to the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Lewis consulted with Dr. Benjamin Rush in Philadelphia about his illness. Rush wrote eleven instructions for Lewis and prescribed his own pills as a remedy. Rush's instructions and pills signify that Lewis was under the care of a physician. Rush stated that Lewis suffered from a bilious condition, which meant a certain type of fever originating in the liver and located on the right side of the hypochondriac region.64

Three months later, on September 14, 1803, Lewis provided more information about his illness. Descending the Ohio River, he wrote that “the fever and ague and bilious fevers here commence their baneful oppression and continue through the whole course of the river with increasing violence as you approach its mouth.”65

One has to wonder, as Lewis traveled down the Ohio on the biggest adventure of his life, why he wrote about a specific and serious illness. Instead of contemplating future geographical wonders, he dwelled on a grim aspect of his life.

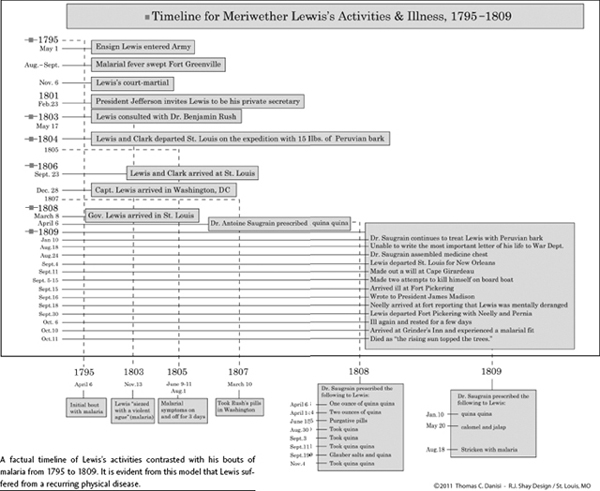

Then, on November 13, when he departed Fort Massac on the Ohio River, he suddenly fell ill and wrote:

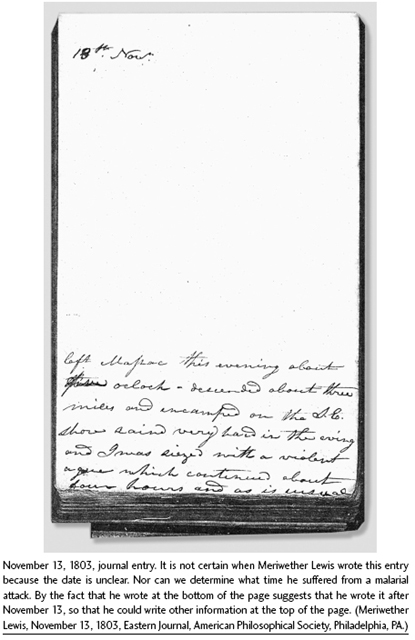

Left Massac this evening about five oclock—descended about three miles and encamped on the S.E. shore raind very hard in eving and I was siezed with a violent ague which continued for about four hours and as is usual was succeeded by a feever which however fortunately abated in some measure by sunrise the next morning.66

The phrase “as is usual” implies that Lewis suffered from a long-standing illness, and this is today a marker of a disease that is periodic and/or episodic in nature. The original journal entry of this date affords a rare view of this event.67 Lewis stated the next day that he was entirely clear of the fever by that evening.68 But he was so weak that he experienced difficulty when writing anything until November 27, which is when he had fully recovered from the malarial episode.69

Historians have stated that what Lewis experienced was “the ague and fever,” which has been equated to a bout of the flu where a person experiences high fever and chills for a short duration. Loge claimed that Lewis “was describing nothing more than a shaking chill—that is, the ague.” Because Lewis didn't couch the malarial attack in terms that we are familiar with today—“never recorded a fever relapse”—Loge stated that Lewis was simply talking about a shaking chill.70 But there is proof to the contrary, and what Lewis described was perfectly understandable to readers of his time.

In the narrowest definition of the ague, it is a shaking chill or an acute fever, and in Webster's International Dictionary, it is defined as “a fever of malarial character attended by paroxysms which occur at regular intervals. Each paroxysm has three stages marked by chill, fever, and sweating.”71 Medical dictionaries are more precise. As far back as 1809 the ague and intermittent fever were interchangeable and “known by cold, hot, and sweating stages, in succession, attending each paroxysm, and followed by an intermission or remission.”72

Dr. John Elliotson in 1842 stated that the “ague shatters the constitution,” and he also explained why malarial sufferers abbreviated their descriptions when writing about them:

[T]he common people limit the word “fever” to the hot, or hot and sweating stages; and denominate only the cold stage “ague;”—so that it is common to hear one of the lower orders that has got “the ague and fever,” but “ague” properly speaking, includes the whole of the three stages.73

When Lewis was on the expedition he had been stricken with malaria several times, but Loge has dismissed this because Lewis “did not have any indication of a malaria-like syndrome.”74 For example, referring to June 11, 1805, which was the end date of a malarial episode, Loge stated that it was “not characteristic of any form of malaria.” Lewis's condition between June 9 and 12, 1805, was indeed characteristic of a bout of dysentery and symptomatic of malaria, which is one of the most common features of that disease, and which originates from a derangement of the liver.75

June 9

I felt myself unwell this morning and took a portion of [glauber] salts from which I feel much releif this evening.

June 10

I still feel myself somewhat unwell with the disentary, but determined to set out in the morning up the South fork or Missouri.

June 11

This morning I felt much better, but somewhat w[e]akened by my disorder. at 8 A.M. I swung my pack, and set forward with my little party.…I determined to take dinner here, but before the meal was prepared I was taken with such violent pain in the intestens that I was unable to partake of the feast of marrowbones. my pain still increased and towards evening was attended with a high fever; finding myself unable to march, I determined to prepare a camp of some willow boughs and remain all night. having brought no medecine with me I resolved to try an experiment with some simples; and the Choke cherry which grew abundanly in the bottom struck my attention; I directed a parsel of the small twigs to be geathered striped of their leaves, cut into pieces of about 2 Inches in length and boiled in water untill a strong black decoction of an astringent bitter tast was produced; at sunset I took a point [pint] of this decoction and abut [about] an hour after repeated the dze [dose] by 10 in the evening I was entirely releived from pain and in fact every symptom of the disorder forsook me; my fever abated, a gentle perspiration was produced and I had a comfortable and refreshing nights rest.

June 12, 1805

This morning I felt myself quite revived, took another portion of my decoction and set out at sunrise.

It would appear from Lewis's summary that the chokecherry plant had reduced the fever and stopped the dysentery but “this is characteristic of the malarial cycle, suggesting that Lewis's relief had more to do with his fever's natural ebbing” than any treatment during the time in which he lived.76

After Lewis returned from the expedition he had several bouts with malaria, including March and July 1807 and throughout 1808–1809. But despite these attacks, Lewis was an active, energetic, and effective governor, which has been little understood until now. Historians have tagged Lewis as a depressed individual, but there is no evidence to prove it—being physically ill with untreatable malaria could be depressing, but actually, Lewis rose above it. From November 1807 until September 1809, Lewis was busily engaged with territorial duties and his letters to officials and friends confirm it.

During the two weeks that Lewis recuperated at Fort Pickering, he had changed his mind about going to New Orleans for two reasons: he didn't want his journals falling into the hands of the British when traveling by boat, and he expressed concern about the heat in the lower country.77 The heat was an expression of a dire malady. Reports coming from the barges on the Mississippi advised to stay clear of New Orleans: an ague and fever epidemic was killing the inhabitants and army personnel. By November of that year, more than 700 soldiers had perished.78

Lewis then departed the fort with Maj. Neelly, Pernier, and the packer, but after resting at a camp, a week later, Neelly had to look for the horses. Alexander Wilson, an ornithologist and a close friend of Lewis, visited the Grinder family seven months after Lewis's death. He interviewed Priscilla Grinder about the events that occurred on the late afternoon of October 10, when Lewis exhibited a recurrent form of malaria:

Lewis…walked backwards and forwards before the door, talking to himself. Sometimes…he would seem as if he were walking up to her; and would suddenly wheel around, and walk back as fast as he could. Supper being ready he sat down, but had not eat…a few mouthfuls when he started up, speaking…in a violent manner. At these times…she observed his face to flush as if it had come on him in a fit.79

Lewis was delirious, and Priscilla Grinder, familiar with this illness, knew what it was. When Neelly interviewed her, he reported that Lewis “reached the house of a Mr. Grinder about sun set, the man of the house being from home, and no person there but a woman who discovering the governor to be deranged gave him up the house & slept herself in one near it.”

Lewis's actions, on that fateful night, were not unique. It may be an aberration from the point of view of healthy patients, but Lewis was a malarial sufferer. Dr. Macculloch corroborated that the treatment that Lewis performed, shooting himself, had been attempted by others as a remedy and that some of these patients had lived thereafter:

[T]his particular aberration…is well known…while I need not do more than suggest one peculiar part of the body which has been often the offending and selected point; the act having been…not always followed by death.80

In a prior chapter medical evidence identified that Meriwether Lewis had malaria and that he had the same set of feelings and desires displayed by Macculloch's patients. Lewis had a certain antipathy toward his head and liver/spleen and wanted to wound it by shooting it, as if the shooting would cure it. Ultimately he was following Macculloch's description, and was one among those malarial patients who wounded “the offending part.” In this scenario, Lewis desired to alleviate his pain but was not trying to terminate his life. The reader must understand that the pain in his head was unbearable and debilitating. As Macculloch pointed out, “There is also a particular part of the body affected by an uneasy but undefinable sensation, such that the mind constantly reverts to it as a source of suffering…or a condition of absolute pain.”

Lewis was driven to shoot the offending part because of the absolute pain.

In sum, the ague made him do it. Lewis probably contracted the disease in 1795. He followed a regimen of treatment prescribed by Dr. Rush and later by Dr. Saugrain, and his actions mirrored those of Macculloch's patients. In light of these facts, Meriwether Lewis did not commit suicide. Lewis was suffering from an acute physiological illness, that is, the ague or malaria. As such, that acute illness was the cause not only of his erratic behavior but also the radical and violent actions he performed upon himself in October 1809.

Historians, in the past, have claimed that Lewis killed himself; my conclusion, as a historian, is that Lewis did not mean to kill himself in his malarial attack. Rather, he, by his actions, meant only to treat his absolute pain.