Maps, no less than narratives, are among our most basic documents, and when they are examined carefully they shed great light on the timeline of history and reveal the growth of knowledge as well as the progress of human endeavors. A history without maps is inconceivable.

Thus, a crucial aspect in the planning of the single most important exploration in American history, that of Thomas Jefferson's Corps of Discovery, the Lewis and Clark Expedition, was to obtain reliable maps to chart their route.

How did Lewis and Clark do this?

The answer to the captains’ success in finding a viable map of the Upper Missouri River is to be found in the story of cartographer James MacKay, a Scotsman who, based on his extensive trading with the Indians in Canada, and on his proficiency in mapmaking and experience in surveying, had been hired to lead the Spanish expedition up to the Missouri in Louisiana territory.

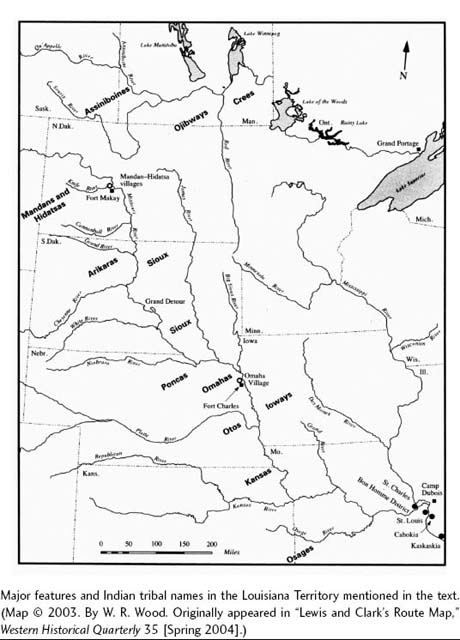

A superficial look at history would indicate that MacKay was only one small player in the international intrigue of land and economic disputes in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. It would suggest that the handwriting on the map, in both French and English, proved that John Evans (MacKay's field assistant) and Nicolas de Finiels (a Frenchman who assisted MacKay and others in various cartographic efforts) contributed to the actual drawing of the map—which is now known as the Indian Office Map.

But a cursory look at history, as always, can be misleading. It is true that it was John Evans who, on that 1795 expedition, traveled the Upper Missouri River to the Mandans while MacKay remained in Fort Charles—795 miles above Saint Louis— and it is logical to think, since it was Evans who explored the Upper Missouri, that he would have been the one to draw the map. Also, there did exist at the time an international aspect of cooperation: MacKay, Evans, Antoine Soulard (surveyor general of Upper Louisiana), and Finiels all assisted one another on cartographic efforts. It is perhaps because of this, combined with Evans's explorations on the Upper Missouri, that historians have denied MacKay's role as the primary draftsman of the Missouri River map. The truth is to be found in detailed detective work.

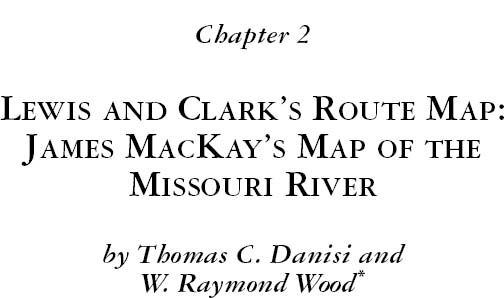

The story begins in the 1790s. At that time, Louisiana encompassed a huge swath of country west of the Mississippi, and distant European powers lacked the means to populate it or patrol its borders. When Spain took control of the region in 1762, British traders in Canada had already begun establishing alliances with the various Indian nations along Louisiana's northern boundary. These alliances enabled the British to make deep forays into Spanish territory without fear of reprisal. It proved very difficult for Spain to wrest control from the British. Beginning in 1789, a few hunters, including Juan Munier and Joseph Garreau, were the first Spanish to explore the Missouri. Jacques d’Eglise followed a year later. These men reported that the British had been stealing the trade from the Spanish and were underselling them in their own territory. Something had to be done and quickly: the Spanish would have to ascend the Missouri, establish relations with the Indian tribes, and somehow win them over from the British.1 In 1791, Spain appointed as governor general of Louisiana the Baron de Carondelet. One of Carondelet's first decrees was to throw open the trade to all subjects of His Catholic Majesty Carlos IV. In that year, Spain learned that the British had established a trading alliance with the river tribes on the Upper Missouri, and, if war broke out, the Spanish would lose control of that river. While Carondelet's decree offered advantages, the Indians had already become allied with the British and thus discouraged Spanish traders from going upriver. This development demanded a strategic plan, and, in 1793, a group of Saint Louis traders formed the “Company of Explorers of the Upper Missouri,” pooling their resources to finance well-equipped expeditions. While the financing appeared to come easily, finding suitable persons to lead the expeditions proved challenging. The first two expeditions, led by Jean Baptiste Truteau and a man named Antoine Lecuyer, made little progress on the Missouri.2 However, in choosing James MacKay to lead the third expedition in 1795, the traders found a well-prepared and uniquely talented man.

MacKay arrived in Canada sometime between 1776 and 1777, and for the next five years his whereabouts are unknown. In 1783, the British traders Holmes and Grant hired him. Robert Grant, an experienced trader from Montreal associated with the North West Company, took him to Grand Portage, the rendezvous for Canadian traders on the north shore of Lake Superior.3 Evidently, James's brother John was also in Grant's outfit, but they separated a year later.4

MacKay was released to go to the Saskatchewan River as a clerk, but he was back on the Assiniboine River for the winter 1786–1787. On returning to Grant in 1787, he was given an opportunity to travel overland to the Mandan and Hidatsa villages on the Missouri River.5 That overland journey was usually made during the winter using dog trains to haul small outfits and bring back peltry and foodstuffs, especially corn. When his contract ended in 1788, MacKay went back to Montreal with the returning canoes. Relations with the Canadian traders soured, however, and he renewed association with his brother, John, in New York City, and began trading in the United States.6 In June 1789, MacKay met with Don Diego Gardoqui, the Spanish chargé in New York City and presented him with a map, “a su modo” of the British—Canadian trade.7

MacKay started a fur-trading partnership with depots in Cahokia, Cincinnati, and New York City.8 He had arrived in Cahokia by September 1791, made acquaintances in Saint Louis that same year, and established a name by 1793.9 On May 20, 1793, Zenon Trudeau, lieutenant governor of Upper Louisiana, wrote to Baron de Carondelet, governor general of Louisiana, that he hoped “to see within a few days a well informed Canadian mozo [young man]” who had been trading with the Mandan nation. He hoped to obtain from him information on the British among those Indians.10 Trudeau and Jacques Clamorgan, director of the Saint Louis—based fur-trading Missouri Company, were so impressed with MacKay's abilities—to make maps, to write and speak the French language, and to trade with a variety of Indian tribes—that they hired him to head an expedition up the Missouri for the company MacKay then left Spanish Louisiana to conclude his business in New York and Cincinnati.11

Two other notable men arrived in Spanish Louisiana at about the same time as MacKay: John Thomas Evans and Antoine Pierre Soulard. Evans had come to the United States looking for a tribe of Welsh Indians he thought might be the Mandans. On October 10, 1792, he arrived in Baltimore, where he stayed and worked for various Welshmen. In March 1794, he departed by boat and landed in New Madrid [present-day Missouri] about two months later. Upon entering Spanish domains, he took the oath of allegiance that the commandant, Thomas Portell, forced on all newcomers. It appears that Evans contracted malaria and stayed with a Welsh couple in New Madrid before he continued on toward Saint Louis. On the way to Saint Louis, Evans became lost and finally turned up at a Spanish post opposite Kaskaskia, deranged from the summer heat. Fortunately, he met another Welshman, the lawyer John Rice Jones, who took care of him on the Illinois side of the river.12 A month later, Jones introduced him to a Cahokia merchant and court clerk, William Arundel. Evans stayed at Arundel's home until Christmas 1794, when he learned about James MacKay's forthcoming expedition up the Missouri River and left for Saint Louis, hoping to join.13 It was an inopportune time for Evans to go to Saint Louis. War with Britain was imminent, and explaining to Zenon Trudeau, the lieutenant governor, that he was on a quest to find a tribe of Welsh Indians must have sounded preposterous to the highest ranking official in Upper Louisiana. Suspicious of British spies entering Spanish country, Trudeau had Evans “[i]mprisoned, loaded with iron and put in the Stoks…in the dead of winter.”14

A few months after Evans was thrown in jail, in February 1794, Antoine Soulard arrived at Sainte Genevieve.15 The commandant of New Bourbon, Pierre Charles Delassus de Luziéres, knew Soulard because he had deserted the naval service at Martinique, France, with one of de Luziéres's sons. This son had told de Luziéres that the two had not wished to recognize the French Republic as their home and had decided to join the family in America.16 The commandant of Sainte Genevieve had fears that Kentuckians might attack Louisiana. With no defenses in the village, Soulard volunteered to help and began “directing the works on the fort” according to the “plans and sketches” of a Flemish engineer, Louis Vandenbemden.17 The work was completed quickly, and Trudeau summoned Soulard to Saint Louis, who arrived there by March 20, 1794.18

In August of that same year, MacKay had gone to Cincinnati to conclude his partnership in his eastern business interests with John Robertson. While in Cincinnati, MacKay met with John Rees, or Rhys, a native of Wales, who told him of Evans's quest for Welsh Indians and gave him a small dictionary of Welsh and Mandan vocabulary. MacKay had been among the Mandans in 1787 but “had heard nothing of a Welch tribe.” When MacKay arrived in Saint Louis a few weeks later, he “sent for, & engaged for [his] assistant Mr. Evans who spoke and wrote the Welch language with facility.”19 MacKay, realizing that Evans could be an asset to the expedition, decided to employ him as his lieutenant and field operator.

The story of the MacKay map of the Missouri River begins when the first expedition for the Missouri Company, headed by Jean Baptiste Truteau, a schoolmaster, left Saint Louis on June 7, 1794. Clamorgan had provided Truteau with a plan or idea so “that he may know his whereabouts.”20 The north half of this plan, taken directly from MacKay's travels in Canada in 1784 through 1788, was the first of its kind and gave a tactical view of where the British traders had encroached upon Spanish soil.21 When MacKay first met Zenon Trudeau and Jacques Clamorgan in May 1793, he had shown them this “topographical idea of the Upper Mississippi and Missouri.”22 MacKay had met with Soulard to help produce a map for Carondelet. Trudeau wrote to Carondelet on November 24, 1794, stating that he was remitting some maps drawn by Soulard “among which was a map of the Missouri river.”23

Trudeau's admission of a Soulard map is interesting; Soulard could not have completed it by himself, because during the summer and autumn months that year he suffered bouts of “most violent fever” and “would have succumbed,” except that Trudeau and his wife took care of him.24 In other words, being so ill, Soulard, who had not been on the Upper Missouri River, could only have completed a map of the river with MacKay's assistance, because MacKay had visited the Upper Missouri River. Nonetheless, Trudeau recommended that Soulard serve as the surveyor of Upper Louisiana, and in December, Soulard made a voyage to New Orleans, where he was appointed surveyor general on February 3, 1795.25

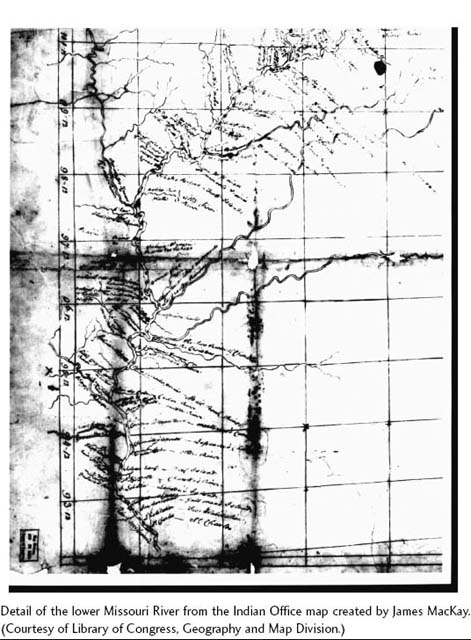

Between January and August 1795, Soulard began surveying land grants in Saint Louis and Cape Girardeau, as well as drafting a large-scale map, “Ydea Topografica,” of the Missouri River Basin.26 The original Spanish map is titled “A Topographical idea of the Upper Mississippi & Missouri that shows the progress of the Spanish Discovery of the Missouri river & the encroachments [or usurpations] of the English companies over the Spanish possessions.”27 The French copy attributes its drawing to Soulard, who completed it in August 1795, though MacKay revised “Ydea Topografica” when he returned from his expedition in 1797.28 Soulard wrote on December 15 of that year that the map was “corrected by one of the voyagers of the company of discovery,” and that he would soon present a map of the Missouri to Manuel Gayoso de Lemos, the new governor general of Louisiana, “much more correct than what I gave you earlier.”29

Charting a river requires at least two people: the surveyor and the draftsman. The surveyor takes measurements and sketches landmarks like islands, bends in the river, and large trees, recording the field notes in a book, while the draftsman draws a grid and translates the measurements from the field notes into a diagram that represents the river. In 1795, charting a river required taking detailed astronomical observations to determine longitude and latitude, the critical east and west directions. William Dunbar, who lived in Spanish Louisiana in the 1790s, had been hired by the Spanish as their astronomer. Dunbar had advanced the science of astronomical observation further than any of the prominent group of Philadelphian astronomers had during this period by “requiring neither assistant nor timepiece.”30 Dunbar was able to reduce the complexity yet raise the bar for accuracy; however, in 1795, James MacKay knew only one method and, by hiring Evans, it presupposed that an assistant was mandatory.31

Near the end of August 1795, the third expedition for the Missouri Company left Saint Louis with a number of objectives: to make a map ascertaining the northern boundary of the province, since no chart had been drawn nor evidence collected that verified the northern extent of Louisiana; to establish forts along the Missouri River; to reach the Mandan in North Dakota; and to find a water route to the Pacific Ocean.32 Governor Carondelet was so pleased with the possibility of finding a water route that he offered a cash prize of 3,000 piasters to the first Spanish subject who could penetrate to the Pacific Ocean via the Missouri River. He also promised to pay the salaries of one hundred men to guard the forts that MacKay would build along the route of that river.33 How such a complex expedition with so few resources was to achieve its goal is a mystery, but MacKay, having been assured that the Missouri Company was well financed, embarked upon the exploration.

The expedition arrived at the Omaha village in Nebraska in mid-October and built Fort Charles, approximately twenty miles south of present-day Sioux City, Iowa. The Omaha chief, Blackbird, had the reputation of being both difficult and tyrannical. He demanded daily communication with MacKay. This meant that MacKay had to remain at the fort when Evans left for the Mandan at the end of November. MacKay realized that Evans would have to continue the survey of the river on his own, and so MacKay taught Evans with precision and gave him a comprehensive list of instructions:

You will keep a journal of each day and month of the year to avoid any error in the observations of the important journey which you are undertaking. In your journal you will place all that will be remarkable in the country that you will traverse; likewise the route, distance, latitude and longitude, when you observe it, also the winds and weather. You will also keep another journal in which you will make note of all the…territory…lakes; rivers; mountains; portages, with their extent and location.34

MacKay also wrote about the accuracy of the observations:

In your route from here to the home of the Ponca, trace out as exactly as possible a general route and distance from the Missouri as well as the rivers which fall into it; and although you cannot take the direction of each turn and current of the Missouri, since you go by land, you can mark the general course of the mountains which will be parallel to each bank. You will observe the same thing for every other river (landmark) which you may see during your journey, whether river, lake, ocean, or chain of mountains which may effect your observations.35

MacKay, in effect, instructed Evans on how to take a detailed set of field notes so that when he received them, MacKay could continue updating the map of the Missouri River. MacKay also reminded Evans that if he ran out of ink to “use the powder, and for want of powder, in the summer you will surely find some fruit whose juice can replace both.”36 Clearly, the man who needed such orders written down could not have been the author of the map.

MacKay also gave Evans a supplemental set of instructions to ensure that Evans's observations, regardless of the distance between them, would remain accurate. He wrote, “As I mean to make Sunday (being a remarkable day) the day for observing the distance of the moon from the sun I wish you to do the same when convenient so that we may be the better able to compare them when you return.” He treated Evans as a novice and his student. His instructions continued:

“I will always make my observations when the sun is on the meridian which will of course give the just time of day. You may draw a meridian line by the north star if you should be a couple of days in one place & if the sky be clear at night if this cannot be you may take it by the compass if you know exactly the variation.” He also told Evans not to reveal his plans to anyone, including Truteau, the leader of the first expedition.37

MacKay had sent a message to the Sioux before Evans left to notify them that an expedition was en route. A few weeks after Evans left Fort Charles, his party came upon a band of Sioux who chased him for an entire day and were about to overtake him when night fell.38 Evans returned to Fort Charles on January 6, 1796, although he left again on January 28.39 It took him two months to reach the Arikara village—traveling seven hundred miles by water and then spending an additional six weeks to talk the Arikaras into letting him journey onward.40 On September 23, Evans arrived at the lower Mandan village, in present-day North Dakota, and found a fort built by the merchants of Montreal that he named Fort Makay [Evans's spelling]. Carrying a formal notice written by MacKay, Evans ordered several British traders on October 8 to leave Spanish soil. The traders were surprised to learn that it was the same James MacKay, a former trader and friend, who was chasing them out of the territory.41

Evans had assumed that supplies were forthcoming, but when none arrived and what he had at Fort Makay ran out, he departed for Saint Louis. MacKay's supplies were also depleted by March 1797, when Clamorgan ordered him to return to Saint Louis. MacKay arrived a few days before May 13. Evans arrived on July 15. Trudeau wrote to Carondelet at the end of May, informing the governor that MacKay had arrived and had already completed a substantial section of the map—the first “three hundred and fifty leagues.”42 When Evans returned from the Mandans, MacKay took the Upper Missouri River data and completed drafting the expedition map. He referred to several documents that were an integral part of the expedition: MacKay's Table of Distances and the journals written by him and Evans.43 The map employed the French language to designate the names of rivers and locations. Jacques Clamorgan, on October 14, 1797, wrote about the map to André Lopez, the intendant at New Orleans:

I am sending to the governor, the well-chartered map at the expenses and fees of the company. I hope that the company will take back its usual vigor without delay and that it will merit in the future by its zealousness and activity in making discoveries, the bounty of the government.44

Two months later, on January 16, 1798, Zenon Trudeau informed Manuel de Gayoso, governor general of Louisiana, that he was sending the river map and “a relación,” or record, of the voyage:

I am enclosing to Your Excellency a relación of the voyage which M. Mackay has made in the Upper Missouri, and the map of the said river, as far as the Mandan nation, made by the same person, which I believe to be the most exact of those which have been formed up to the present, since M. Mackay was instructed in the matter and knew that he had pledged himself to procure this map with careful attention for the government. Up to the present time the government had only [information] intellectually based upon the simple relaciónes of the hunters.45

Trudeau wrote again to Gayoso on March 5, 1798, explaining that Auguste Chouteau would deliver another copy of the map.

I have spoken to you in different letters about Mr. Mackay and this would be a good occasion to let you meet/know him. Even if Mr. Mackay would not ask for the favor of being presented to you, I will take the liberty of asking you to look upon him with interest. I can assure you that he deserves it, and in a few days you are going to appreciate him as I and all persons that already know him do. Can Mackay meet with you to talk about the Missouri? He is the author of the map that Mr. Chouteau is going to give you.46

MacKay had suggested to Trudeau that he would make another map of the Missouri more detailed than the one being sent with Chouteau. Trudeau wrote to Gayoso speaking about MacKay and the maps, “He also has the intention [literally: ambition] of continuing to make another complete one, but the expenses will be too considerable to propose them to you.”47 As Trudeau noted, the expenses would certainly have been prohibitive, since the Missouri Company had expended all of its resources on the three previous expeditions. MacKay departed in late March 1798 to meet Gayoso and talk with him about the success of the expedition. John Evans, after completing his work as a deputy surveyor, departed for New Orleans in the beginning of July.

More evidence disputes that either Evans or Finiels drafted the Missouri River map. In 1908, Frederick Teggart discussed an Evans map that came into the possession of John Hay and William Henry Harrison.48 In late October 1797, Soulard had appointed Evans the deputy surveyor of Cape Girardeau, and on November 7, Evans had departed for the district with surveying instructions.49 Sometime in May 1798, a flood devastated the district and Evans lost most of his belongings. Intent on going to New Orleans to meet MacKay and Gayoso, he tried to sell his surveying instruments and asked Bartholomew Cousin, the newly appointed surveyor of Cape Girardeau, to help him with his map and to buy his instruments. Cousin replied that he had no use for his instruments and that his assistant would “send you your…chart which I have not divided because I don't remember on what scale it is drawn, nor what is the exact longitude and latitude of any plan on it….”50 In the meantime, Jones gave the incomplete chart to John Hay, who had the means to complete it.51 Hay had been a British trader and had a merchant store established at Cahokia under the name Todd and Hay. Events that were to thrust the map into the limelight began to converge: in January 1801, Jones was appointed attorney general of the Indiana Territory and moved to Vincennes, the capital.52 When William Henry Harrison, governor of the territory, was apprised of the expedition in 1803, Jones sent the map to him. Harrison wrote to William Clark on November 13, 1803, informing him that he had the map copied and “now send it to you by Post rider.”53

On November 26, 1803, Harrison wrote President Jefferson that he was sending a “map which is a copy of the manuscript map of Mr. Evans who ascended the Missouri river by order of the Sp. gov't further than any other person.”54 He wrote to Lewis on January 13, 1804, that he was sending him a map, which was a copy of the copy from Harrison: “I now enclose a map of the Missouri as far as the Mandans, 12. or 1500. miles I presume above its mouth. It is said to be very accurate, having been done by a mr. [sic] Evans by order of the Spanish Government. But whether he corrected by astronomical observations or not we are not informed.”55 The map was indeed incorrect. MacKay had given Evans a raw copy, a template of the map, because he believed Evans had the ability to complete it.

Before MacKay went to New Orleans, Finiels drafted a map for him. In fact, he and Finiels assisted each other, which has not been fully understood because the dates of their mapmaking overlap. They both produced maps during 1797 and 1798: MacKay from May to December 1797; Finiels from August 1797 to June 1798. Finiels arrived in Saint Louis on June 3, 1797. He had been hired in Philadelphia to oversee the building of defenses at Saint Louis. But Carlos Howard, the military commandant, refused to employ him. Howard had no explicit order from Carondelet and believed that Finiels, an artillerist engineer, was not as competent as Louis Vandenbemden, a fortifications engineer.56 Finiels decided to embark upon a private mapping project during 1797–1798.

Finiels refers to a map completed in mid-1798. “La carte de cette Riviere que j'ai dressée en 1798 sur les memoirs ds/des Mess./Messieurs MacKay et Evans donnera une notion trés exacte de la partie de son cours que l'on peut regarder comme la mieux connue jusques apresant.” (“The map of this river that I drew up in 1798 [based] upon the accounts of Messieurs MacKay and Evans will give a very exact notion/idea of its [the river's] course which one can regard as the best known up to the present”).57 The Finiels map, which measures ten feet long and a yard wide, shows the Missouri River for more than eighty miles west of its mouth.

This map is Finiels's greatest achievement, a colossal, unauthorized, and personal project: mapping the central Mississippi Valley. His idea for it was likely due to MacKay's arrival from the Upper Missouri, replete with fresh data regarding the expedition and Soulard's “Ydea Topografica,” as well as the fact that Soulard possessed the surveying measurements for many of the villages. In terms of artistry and accuracy of detail, Finiels's map of the central Mississippi Valley stands apart from any other produced in the history of North America.58 Even now, Finiels's hand translates an ancient time into a living one. The map details Saint Louis, Carondelet, Prairie du Pont (“Prairie of the Bridge,” now Dupo), Cahokia, River Des Peres, Chouteau's Pond, the Commonfields, Cape Girardeau, Sainte Genevieve, and New Madrid. Tiny red squares represent houses, and he depicts each field under cultivation, the hills, and the green-tinted Mississippi River. The breadth and majesty of this map argue for the amount of time and concentration Finiels took to complete it.

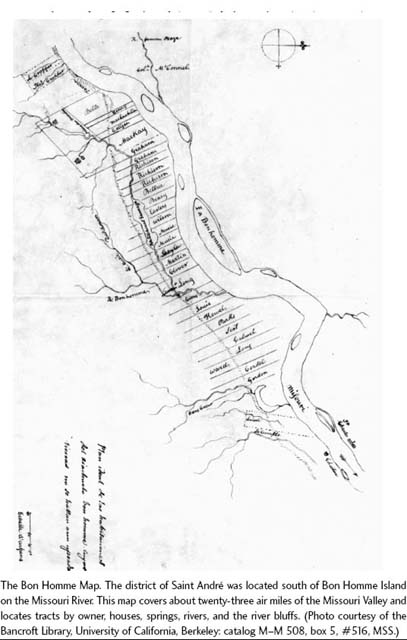

The time necessary to complete this map precludes the idea that Finiels could have also drafted a Missouri River map laden with all the complexities of a course of 1,510 miles. But surprisingly, Finiels describes another map that he drafted in 1797 near the Bon Homme Creek on the Missouri River. From the French manuscript of “Notice sur la Louisiane Supérieure” (“An Account of Upper Louisiana”), Finiels states that he made a map for MacKay—not the Missouri Company: “C'est sur ses memoires et sur ses relevés que j'ai dressé pour lui en 1797 la derniere carte du Missouri.” (“It is upon his written statement and upon his account that I drew up for him in 1797 the latest map of the Missouri.”)59 Finiels's attempts to make a distinction between MacKay's Missouri River map (a version of the Indian Office map) and the one that he drafted for MacKay that was of an unnamed district; thus the appellation “latest map of the Missouri.” The map is titled “Plan ideal de las habitaciones del riachuelo bon homme cuyos tierras no se hallan aun apeadas,” or “An ideal map of the habitations of the Bon Homme creek whose lands have not been delineated [up until now].”60 It was a proposed plan of the district subject to approval by the governor and soon to be given the name Saint André. Trudeau forwarded the map to Gayoso on February 28, 1798, adding his description of the progress of the new settlement:

I am sending you a small ideal map of the American's habitations, situated on the shores of the Missouri and the Bonhomme creek. Part of these are already established and in all of them they made the corn harvest last year; currently we are working to construct a mill over that which belongs to Lorenzo Long, who has brought in (for this) black stones and very intelligent workers, such that I have no doubt that this place will be prosperous before two years, for a distance from seven necessity of appointing there a trustworthy person as Commander and who can correspond with me at least in the French language. I propose to you Mr. James (Don Juan) MacKay who has already held from your predecessor the title of Commander of the forts which are to be constructed in the Upper Missouri, he is well known as an intelligent and prudent man and the only one who speaks the French language among those who hold lands in the said place and that you can have confidence in his fidelity and it is equally well that the above-mentioned Mr. MacKay be named captain of the militia company that needs to be formed out of the said inhabitants. And as I have expressed to you, the commanders of the town of Ste. Genevieve, New Bourbon and Cape Girardeau have a compensation of 800 pesos yearly, the others equally deserve it and among them Mr. MacKay. I find that it is appropriate that you appoint him to that which I propose to you.61

MacKay's interest in the area of this plan came naturally. Once he had completed the chart for Clamorgan in October, he began looking for a place to live. The Bon Homme settlement attracted him probably because it was in need of a commandant.62 Therefore, he set himself to making a plan of the district with Finiels's assistance. Like Soulard, in 1795, when Trudeau proposed him as surveyor general, MacKay also demonstrated his abilities to the lieutenant governor. Evidently, the idea worked. MacKay had already chosen the location for the tract he was asking Trudeau to grant him. Trudeau agreed, granting MacKay about 3,700 acres near the Bon Homme Creek on December 23, 1797.63 MacKay's plan of the Bon Homme district is a small-scale map, illustrating houses, rivers, islands, hills, lot sizes, and the names of the owners of lots. This map is unique to MacKay's heritage; however, when comparing it to Finiels's Mississippi Valley map, a recognizable feature stands out: the manner in which the rivers are drawn. The shape and contours of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers, and the rendering of their sandbars, are so similar that they appear to be made by the same hand. To the untrained eye, the technical skills between MacKay and Finiels would have been difficult to ascertain, but it was their artistic treatment that helped solve who drafted which map. Unaware of the Bon Homme plan, historians have mistakenly credited Finiels with the drafting of MacKay's Missouri River map.64 But an identifiable design element exists on MacKay's Missouri River map and on the Bon Homme plan that does not appear on Finiels's map: it is the fleur-des-lis drawn by MacKay on the north arrow. This element, an unconventional map symbol, assisted in the recognition of his maps.

When MacKay began as commandant at Saint André in November 1798, he continued surveying while handling all civil and criminal matters in the district.65 Five months earlier, when Gayoso appointed Charles de Lassus as lieutenant governor, he told him that MacKay merited his special attention. De Lassus was instructed to help MacKay fulfill his duties and to pay particular attention in “obtaining the most rapid and exact information concerning the intentions of the traders from Canada in Spanish territory.”66 In 1802, François Perrin du Lac allegedly made a voyage up the Missouri and produced a map that he ambiguously credited to “un ancien traiteur de la rivière des Illinois….” 67 Historian Annie Abel's claim that Perrin du Lac was referring to Jean Baptiste Truteau as the ancient trader gave rise to an arduous debate over MacKay's expertise in the ensuing decades.68

One of Meriwether Lewis's primary goals when planning the expedition was to find the most up-to-date maps of the Missouri River, and he had obtained several of them before arriving in Saint Louis, including one by Aaron Arrowsmith and another by David Thompson. On December 8, 1803, Lewis arrived in Saint Louis without William Clark but accompanied by two interpreters from Cahokia, John Hay and Nicholas Jarrot. Lewis met with Charles de Lassus, the lieutenant governor, who had become suspicious about the expedition because Lewis presented a French passport instead of a Spanish one. De Lassus told Lewis that if the papers had been in the name of the Spanish king, there would have been no difficulty granting the expedition access to the Missouri. De Lassus needed time to write to his superiors in New Orleans and ask permission; he told Lewis he would have an answer by the spring of 1804. Lewis “agreed to wait” and said that he would spend the winter on the east side of the Mississippi.69

A day later, Clark and the remainder of the corps made their formal entrance in Saint Louis. “Under Sales & Cullers,” Clark noted, they put ashore where “hundreds Came to the bank to view us.” Clark was surprised to see some of his old friends from Vincennes and Kaskaskia. While Lewis remained in Saint Louis tending to business affairs, Clark “proceeded on” to find a site where the group could establish the temporary encampment.70 Lewis had asked de Lassus if he could meet with individuals in Saint Louis who might be able to help him with the geographic information of the country. Although de Lassus granted permission, Lewis wrote that, while the inhabitants were eager to help, “every thing must be obtained by stealth.” Furthermore, Lewis stated that everything underwent his examination and “you may readily conceive the restraint which exists on many points.” For example, when Lewis met with some merchants, he reported that they were all afraid of de Lassus, especially the inhabitants, who moved more “as tho’ the fear of the Commandant, than that of god, was before their eyes….” Even some of the wealthiest had been jailed for slight offenses, which “has produced a general dread of [de Lassus] among all classes of the people.” Antoine Soulard, surveyor general of Upper Louisiana, had agreed to let Lewis copy government information from the 1800 census, but when he realized that Lewis was going to copy the whole document, he expressed extreme fear. Soulard became so agitated that Lewis desisted and wrote “if it were known that he had given me permission to copy an official paper…it would injure him with his government.”71 Although full of trepidation, Soulard did help Lewis, but he failed to obtain the genuine map of the Missouri River. If Lewis and Clark were to depend on MacKay's map for the first part of their journey, it was absolutely urgent to meet with him.

But de Lassus had only granted the Americans access to Saint Louis, and MacKay, commandant of Saint André, wrote that his district was a “long journey” from there. Finiels believed that a trip to Saint Charles by water took about two days and Saint André was almost nine miles further west.72 Delays continued to hamper Lewis, and now the most important person in Upper Louisiana lay out of reach. If the Scotsman were truly an expert, then they probably would meet often to strategize and make maps, yet it could be the height of summer before they departed.

Jefferson believed that the transfer of the country would take place at the end of December, and Lewis had relied on that information. Henry Dearborn, the secretary of war, had approved a journey up the Missouri in July 1803, and when Lewis wrote to Jefferson on October 3 from Cincinnati, he confirmed that he would “make a tour this winter on horseback of some hundred miles…on the South side of the Missouri.” He also thought that he could prevail on William Clark “to undertake a similar excurtion through some other portion of the country.” Lewis had hoped that when he arrived in Saint Louis, Louisiana would have been transferred to American soil, so that by February or March 1, he would have procured additional information about the country that would further attest “to the utility” of the expedition. In a letter dated November 16, Jefferson cautioned Lewis to revise his plans because he believed by the time Lewis arrived in Saint Louis, the Missouri River would begin to freeze. He thought that Lewis should remain at Cahokia or Kaskaskia for the winter and gain the necessary information he had requested months earlier instead of taking an ambiguous trip that might incur Spanish opposition and be “exposed to risques,” which Jefferson wanted to avoid at all cost.73

In the meantime, Clark found an excellent site for the military encampment opposite the mouth of the Missouri River and named it Camp Dubois. Apparently, the site was well-known to the local population too, and after Clark had landed at the bank, several canoes of drunken Indians managed to camp near him. In the following days, Clark noted Indians paddling up and down the Mississippi who undoubtedly alerted villagers at Portage des Sioux of the American encampment. Portage des Sioux, located on the west bank of the Mississippi, was the closest Spanish settlement to Camp Dubois, about five miles up the Mississippi. Samuel Griffith, an American farmer from Portage des Sioux, visited Clark on December 16, 23, and 24. Clark ordered John Shields to accompany Griffith to purchase dairy items and Shields returned on Christmas Day with “a cheese and 4 lb butter.”74

Jefferson had sent another letter repeating his orders to Lewis that he should not enter the Missouri until spring, to which Lewis had already indicated his compliance in his December 28 letter. Still, the most essential part of the expedition, examining an accurate map, was out of their grasp. Deciding not to wait any longer, they implemented a plan that has remained hidden for two centuries. Lewis and Clark dispatched Private Joseph Field up the Missouri to locate James MacKay and invite him to Camp Dubois. Field traveled “30 miles up” river to Saint André, where MacKay was commandant.75

The journal entry on January 10, 1804, reveals that the historic meeting between Lewis and Clark and MacKay was kept secret. Lewis and Clark ordered Field up the Missouri regardless of the subtle illegality. While de Lassus had granted access to Saint Louis, where he could monitor their activities, he certainly did not intend for MacKay to reveal government information. Yet, would the Saint André commandant accept the invitation? If he did, he would have to evade telling de Lassus. And if he brought the official map of the Missouri River, a classified government document, that, too, would be illegal. But MacKay took the risk because he needed a job. He learned in September 1803 that the United States had bought Louisiana, and he had informed a Kentucky congressman that becoming an American citizen would deprive him of his office and salary.76 By handing over the genuine map to Lewis and Clark, updated with an additional five years of river information, MacKay would demonstrate his allegiance to the new American government.

The journal entries preceding January 10 were brief, and Clark does not mention when he sent Private Field to locate MacKay. Field probably left on January 7, the same day that Clark began drawing a map of the Missouri River “for the purpose of correcting from the information which I may get of the countrey to the NW.”77 It may have taken Field until the morning of January 9 to find MacKay, who had witnessed the signing of a warranty deed at Saint André. Later in the day, MacKay went to Marais des Lairds (Bridgeton, Missouri) to witness and authorize other documents and then went to Portage des Sioux. The portage was a thin strip of land, a peninsula between the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers north of Camp Dubois.78 After surveying some lots at Portage des Sioux on January 10, MacKay made his way to Lewis and Clark's headquarters at Wood River.79

As Field returned to Camp Dubois, Clark watched the private cross the Mississippi “between the Sheets of floating Ice with Some risque.…” Suspicious that Field took too long to return, Clark questioned him about the trip and was told that it had been impossible for Field to cross, for “the Ice run so thick in the Missourie.” That took time. Clark also didn't like the fact that Field had remained “so long” on the Missouri where he likely was recognized by the inhabitants. Field allayed Clark's fears by saying “that the people is greatly in favour of the Americans.” Field returned at 1:00 p.m., and MacKay arrived at camp some time thereafter.80

The meeting probably was long. Due to the winter weather, the afternoon hour when MacKay arrived, and the fact they needed much time to discuss the intricacies of a river map written in French, MacKay stayed overnight and possibly longer. Clark's journal entries for the next two days were short; he continued to complain of being ill due to the severe “Ducking” on January 9 and indicated that Lewis may have left the camp late on January 12. By January 21, Clark began making detailed calculations based on the distances from Camp Dubois to the Mandans, from the Mandans to the Rocky Mountains, and from the mountains to the Pacific.81

Finally, de Lassus received official word that Louisiana had indeed been sold to the United States. On February 21, he wrote to Capt. Amos Stoddard, the American military official who was to oversee the transfer of the country, and informed him that they should meet. They agreed to the dates to transfer ownership: on March 9, Spain would transfer the country to France and on March 10, France would transfer it to the United States. By March 21, Lewis and Clark had traveled up the Missouri with Spanish Osage Indian agent Pierre Chouteau and Charles Gratiot, a wealthy landowner. Sometime in the spring of 1804, Lewis and Clark drafted a new map based on previous maps made by MacKay, Soulard, Chouteau, and on information gleaned from traders. That map was sent to President Jefferson with Chouteau, who later accompanied an Osage Indian delegation to Washington in July 1804.82

The convoluted history of the map of the Missouri River as high as the Mandan and Hidatsa villages is an important but overlooked detail of the march of the Corps of Discovery. The background of James MacKay and the contribution of his invaluable map shows a curious international progression to what is usually regarded as a strictly national enterprise. It was a transplanted Scot with a history of British service who, at personal risk, provided the link between the preceding Spanish and fleeting French regime to the United States’ assumption of authority in Louisiana. Lewis and Clark's predecessors had already carefully laid out a third of the landmarks that the expedition's members would note in their journals—landmarks that had been named by French voyageurs nearly a century earlier, and that, indeed, persist as toponyms (though often in English translation) to this day.