When Meriwether Lewis and William Clark first arrived in Kaskaskia, Illinois, with a skeletal crew of expedition members on November 29, 1803, Lewis met several individuals from the Indiana territorial government.1 Unknown to Lewis, the purpose of their meeting was procuring lucrative positions in the newly bought Louisiana territory. While historians have described the “Louisiana Purchase” many times, an essential part of the story has been missing for more than two centuries, leading to a misinterpretation of the facts.2 How Lewis was swindled in late 1803 requires some explanation and a short history on how the Americans acquired Louisiana.

Louisiana, the territory encompassing the Mississippi River and its tributaries, was claimed by the French in the seventeenth century. The portion of the territory to the west of the Mississippi, but including the “Isle of Orleans” and the city of New Orleans, was passed to the Spanish in 1762, prior to the end of the French and Indian War, to ensure that it did not become a possession of the British in the war settlement. The French under Napoleon wanted Louisiana back in 1800 as part of a scheme to revitalize Caribbean sugar cane interests, using Louisiana as a granary to feed Caribbean slaves. The revolution begun by Toussaint L'Overture in Haiti, coupled with yellow fever, doomed Napoleon's scheme, and by 1803, strapped for cash in the face of impending warfare with Great Britain, Napoleon was willing to sell it to a willing buyer: the United States. Louisiana was important to the Americans not for the lands west of the Mississippi, but rather because it contained New Orleans, and with it the right of free passage down the Mississippi, allowing Ohio River and Illinois farmers to take their goods to market. The territory, sight unseen, had cost the nation about fifteen million dollars, and having bought it, President Thomas Jefferson wanted to explore it. Jefferson's dream of cross-continental exploration had once been an ambition of his father, Peter Jefferson, and Thomas had tried to inaugurate at least four expeditions, all of which failed, prior to his presidency. He believed that a small military scouting party with expertise in the sciences could comprise an effective exploration team, and he appointed his private secretary, Lewis, as expedition leader. But before Lewis stepped into Louisiana, other events transpired that would shape his future.

The Northwest Territory was a prize of the American War of Independence, which extended the reach of the United States to the east bank of the Mississippi. Many Americans on the east coast were eager to exploit or homestead these new lands, some of which were divided into land grants as rewards to Revolutionary War veterans. Resistance from consolidated Indian tribal groups prevented easy settlement, however, and it was not until the signing of the Treaty of Greenville with the Indians in 1795, coupled with the clarification of national boundaries in the Jay Treaty with Great Britain of 1794, that the area was truly ready for settlement, and it was soon divided into the Indiana and Ohio territories.

Jefferson learned in the latter half of 1802 that Spain had secretly retroceded Louisiana to France. On October 16, 1802, top-ranking Spanish officials at New Orleans closed the port to Americans bringing goods from the north in reaction to reading about the retrocession. The Spanish intendant at New Orleans, two days later, issued a proclamation canceling the American right of deposit at that city. He pointed out that the treaty of San Lorenzo, signed by the United States and Spain in 1795, called for the right of deposit to last three years. The three years were long since up, Europe was at peace, and he must consequently close it until the king at Madrid should order it opened. The proclamation was a bombshell. Western trade was based on the free deposit at New Orleans, and the economic health of thousands of people depended on it. On the afternoon of October 18, two American flatboats reached the city and tied up, as usual, at the muddy batture just above the town, but were forbidden to land. Recalling the proverbial toughness of the men who handled the flatboats, the official who forbade their landing did not go unguarded. The news of the closure swept back up the river and created a storm of controversy. Demands for action were made and a letter published in the Kentucky Gazette that stated that “the reptile Spaniards” acted “in a hostile manner…with degrading remarks that the people of the United States have no national character.”3

Forbidding Americans access to New Orleans was in direct conflict with the 1795 treaty of San Lorenzo between Spain and the United States, which allowed Americans the right of import and export without paying a tariff.4 This event led Jefferson to send his diplomats to France to buy New Orleans. At the end of February 1803, Napoleon sold Louisiana to fund his war chest in Europe, and by July 1803, the news of the Louisiana Purchase had spread to the east side of the Mississippi River.5

Speculation ran the gamut in the Indiana Territory, which was located east of the Mississippi; some said that the territory would be extended to include Louisiana.6 A sliver of the Indiana Territory population eyed Louisiana in a different light altogether, and speculators hoped to acquire precious tracts of mineral land. The mining country in Upper Louisiana around the district of Sainte Genevieve held an abundance of lead ore, more pure than in the United States, and since lead was used in the manufacture of ordnance materials, the most potentially lucrative portion of the new territory was directly across the river from Kaskaskia.

A flurry of activity began in the Indiana Territory in the summer of 1802. John Rice Jones, the attorney general, invited the US War Department to locate a military camp on his land in Kaskaskia, for free. The War Department accepted his “liberal and patriotic proposal,” and by autumn a military company of about fifty men, commanded by Capt. Russell Bissell, occupied a piece of his land.7 Six months later, another company of troops was sent out to Kaskaskia under the command of Capt. Amos Stoddard, who would preside over the transfer of the territory.8

Many American citizens did not want the United States to buy Louisiana, and some members of Congress voiced their concerns that the Louisiana population had no idea of a democratic government. They viewed the French and Spanish inhabitants as an ignorant people because they had lived under a monarchy.9 President Jefferson agreed that “our new fellow citizens are as yet as incapable of self government as children.”10

Other viewpoints were also expressed. Too much was at stake, according to the citizens of Knox, Saint Clair, and Randolph Counties, in the Indiana Territory (today's southern Illinois), who petitioned Congress, claiming that lands on the east side of the Mississippi were poor and limited while the new lands on the west side were far more attractive.11 While petitions galvanized attention on a particular problem, a more intensified approach emerged when Indiana Territory officials put themselves on the line and pitched a specific and alarming cause. Indiana territorial judge Thomas T. Davis was the first to report land fraud in Upper Louisiana on October 17, 1803. From Kaskaskia, Davis wrote to John Breckinridge, a Kentucky senator, asking him for the appointment as governor of the new territory, and explaining the land fraud issue in a roundabout way:

You were very friendly in procuring me this Judgship; but as I expect a Division of the Territory to take place…I must ask the favor of you to nominate me to the President as Governor to the new Territory. I am persuaded that my General Acquaintance with the people & the country will render the appointment popular. The United-States will be greatly imposed on by the Spanish Officers who are to this Day Granting large Tracts of Land to individuals & Dating them back so as to bear Date before the late Treaty. Some Deeds are made to men who have been Dead 15 or 20 Years and Regular Transfers to appearance to the present holders—the frauds are numerous & Americans chiefly Concerned.12

John Rice Jones also sent a letter from Kaskaskia the following day, but sent it anonymously to Albert Gallatin, President Jefferson's secretary of the treasury, which was subsequently printed for Congress and later included in the American State Papers.

You have no guess how the United States are imposed on by the Spanish officers, since they have heard of the cession of Louisiana: grants are daily making for large tracts of land and dated back; some made to men who have been dead fifteen or twenty years, and transferred down to the present holders. These grants are made to Americans, with a reserve of interest to the officer who makes them; within fifteen days the following places have been granted, to wit: forty-five acres choice of the lead mines…the iron mine on Wine creek, with ten thousand acres around it…the Common touching St. Louis…and many other grants of ten, fifteen, twenty, and thirty thousand acres.…I could name persons as well as places.13

Isaac Darnielle, a lawyer from Cahokia, also wrote to Breckinridge in October and believed that Upper Louisiana was to be joined with the Indiana Territory Darnielle opposed the plan: he felt that a majority of designing men had been appointed to the Indiana government and “occupied places sufficient to give them influence over the Ignorant and uninformed part of the people.” They could be elected to places of primary importance in the government of Upper Louisiana. He also warned the senator that John Rice Jones was “capable of natural and acquired abilities…a man of bad character….”14

The following month, President Jefferson wrote to Gallatin about the land problems in Spanish Louisiana:

There are a great number of Americans in that territory whom Spain attracted thither by the bait of concessions fifteen or twenty years ago, and who will have profited by the facility of the moment to acquire land for but little. Many adventurers from the east bank will also have made purchases, and in those wildernesses, possession is a title that the law can not easily contest.15

In the meantime, Kaskaskia became the headquarters for Jones and Davis, who awaited the arrival of President Jefferson's point man, Meriwether Lewis. The purpose of Lewis's landing at Kaskaskia was to gather supplies and to enlist soldiers from Bissell's and Stoddard's companies for the western expedition. On December 3, 1803, William Clark departed upriver while Lewis remained behind to meet with Davis and Jones.16

Davis had just returned from Upper Louisiana and was confident that there would be no opposition to the United States taking possession. The two informed Lewis and Stoddard of the land fraud issue, and Jones departed at the end of November to uncover more details in Sainte Genevieve. He returned to Kaskaskia at the beginning of January and met with Lewis and Stoddard.17

During my stay in the Illinois, I discovered that a scheme of iniquity had for sometime been practicing on the…Spanish side of the Mississippi to defraud the United States of a considerable quantity of land. The method…was to make large grants of land to individuals dated above three years ago…. Information hereof had been made some weeks since by Capn M. Lewis to the President and by Capn Stoddard of the Artillery who has received orders to take possession of St. Louis & appointed commandant there…. I have therefor little doubt but that proper precaution will be taken to invalidate these iniquitous and fraudulent grants.18

Ten days into the new year, Stoddard sent a disturbing report to President Jefferson. He claimed that Zenon Trudeau, the former Spanish lieutenant governor of Upper Louisiana from 1792 to 1799, was the mastermind behind the land fraud. Jones had tangible proof that Trudeau, who had lived in Saint Louis, was “induced by the speculators to sign a number of blank sheets of paper which were used as the basis of large land claims.”

The Attorney General of the Indiana Territory, who, a few days since, visited the Louisiana side, has given me some information which I think it my duty to communicate.

Attempts are now making to defraud the United States [of]…nearly…two hundred thousand acres of land, including all the best mines, have been surveyed to various individuals in the course of a few weeks past. All the official papers…bear the signature of M.—the predecessor of the present lieutenant-governor…. This state of things has suggested the possibility of a successful fraud; and the progress of it will probably turn out to be this: M…who was certainly authorized to cause surveys of land to be made to settlers has been prevailed on to put his signature to blank papers. It is now five years since M.—was commandant of Upper Louisiana, to which these papers appear to be antedated.19

The Stoddard report revolved around one event that occurred in 1799 and resulted in a monstrous land speculation scheme in the Sainte Genevieve mining district. To this day, no one has discovered how Jones acquired this damaging information and for what purpose. It not only condemned Trudeau but also ruined the reputation of several Spanish officers with the incoming American administration. What has not previously been uncovered by historians is that the Stoddard report was influenced and contrived by two avid land speculators and partners, Moses Austin and John Rice Jones, who were “joint claimants” in the largest and most profitable lead mine in Upper Louisiana from 1798 to 1812.20 Furthermore, the blank sheets of paper known as the “Trudeau concessions” originated with Austin in 1799, although we are led to believe that the emergence of those blanks occurred in 1803.21

Austin and Jones concocted this scheme to deliberately freeze the mineral land wealth in Sainte Genevieve. The reason why they did this is because they did not want the Sainte Genevieve habitants to acquire mineral land concessions and wanted the lead mines for themselves and for their American friends. A time lag preceded the news of both the retrocession and the sale of Louisiana, which caught Upper Louisiana residents unaware of their circumstances, and at the beginning of September 1803, the so-called landgrab in Upper Louisiana exploded.22 The landgrab was initiated because the habitants feared that the American government would not honor their simple system of conceded lands and petitioned the commandants for surveys.

The largest amount of surveying occurred in the Sainte Genevieve district and included ten mines of varying size that had been worked intermittently for years, owing to deadly attacks from the Indians.23 Although working the mines was perilous, the miners had no choice, since mining lead was their sole (and very lucrative) occupation.

Most of the habitants lived on and cultivated a part of their land concession, but the process of having a land grant confirmed or completing a title under the Spanish involved several steps. A habitant had to address the commandant of the district, either orally, because many of the inhabitants could not write, or in writing, in what was commonly known as a petition or requête. The requête was a letter of introduction detailing the petitioner's accomplishments and goals as well as a request for title to the desired land. Depending upon the commandant's recommendation, the lieutenant governor would then approve the requête. In other cases, the inhabitant did not petition the commandant, but simply stepped onto a vacant tract of land and acquired it. The lieutenant governor told the inhabitants that “their best titles were their axes and hoes,” which was the only proof needed to show cultivation or habitation.24

The next step was to have the land surveyed, which in almost all of the concessions was not performed because it cost more than the land was worth. Completing the title involved taking the papers to New Orleans, where it passed through four to seven offices, to have it recorded.25 In the history of Upper Louisiana, only eleven concessions had a complete title.26

Historians have presented an alternate account of what transpired a few months before the transfer of Louisiana—that Spanish officials conspired against the American government and doled out the royal domain to friends, relatives, and to themselves.27 In reality, the habitants’ livelihood was at a stake—they lived a meager existence, at the poverty level, and bartered in furs and grains. They worked their land, extracting minerals or selling produce. When Upper Louisiana officials became cognizant that the United States would be their new sovereign, they realized that the habitants were in jeopardy of losing their land concessions, since they had no papers that verified ownership. It was at this moment in time that Austin could see that the mineral lands that he had selected might fall into the wrong hands. Austin and Jones decided to create a diversion that has not been understood until recently.28 A few paragraphs of explanation will bring their scheme into focus.29

In the year 1797, Moses Austin, a successful Virginia miner, found that he was competing with the lead coming out of Spanish Louisiana. He decided to travel to Sainte Genevieve and assess an opportunity for greater employment and profit. Sainte Genevieve lies across the Mississippi River from Kaskaskia, and it is where Austin first met John Rice Jones, who offered to accompany him as his guide and interpreter.30 Upon their arrival in the mining district, Austin verified that the purity of the ore was superior to Virginia lead. In addition, it was cheaper, more abundant, more enriched, and was also untaxed. He decided to move to Sainte Genevieve and become a Spanish subject.31

Austin formed a partnership with Jones and the commandants from Sainte Genevieve and New Bourbon on January 26, 1797.32 The partnership was necessary in order to be granted land in the Spanish country, otherwise the commandants would have opposed the grant. Austin had also promised that he would bring thirty American families with him and that they would also receive land concessions.33 Austin was granted three square miles of mineral land, 6,085 acres, and provisions were made to dispense those land concessions to his followers. In July 1799, when a new lieutenant governor took office, a survey had not been completed for Austin, nor had the orders of surveys been obtained for Austin's followers.34 This was because five of Austin's followers had yet to ask for the acreage, since they had not decided where to locate their land concessions.35

The surveyor general of Upper Louisiana, Antoine Soulard, asked the outgoing lieutenant governor, Zenon Trudeau, to leave with him eight blank but signed land concessions “to be delivered to…Mr. Austin's followers.”36 Saint Louis is ninety miles from Sainte Genevieve, but in 1799 it took weeks to arrive at that location. Soulard gave the concession blanks to an officer who was traveling to Sainte Genevieve to deliver them to Austin so that he could complete the names and quantities.37 A few months later, Soulard and Austin met and Soulard noted that Austin had signed his name to five of the petitions instead of the petitions being signed by his followers. When Soulard called his attention to it, Austin said that some of his followers were absent from the country. This was not possible, since Austin already knew which followers had come with him from Virginia. In the fall of 1803, Soulard requested that Austin make the survey payments, but Austin remarked that his people were not satisfied with the concessions. Soulard then asked Austin to return the concessions, but only five were delivered.38 Austin retained three of the blanks.39 A few weeks later, Jones showed them to Lewis and Stoddard during their meeting in January 1804. Jones passed along his version of the land grant situation in the new territory to President Jefferson on February 11, 1804.40

[F]rom the Information of Capt. Lewis, who I had the pleasure of seeing at Cahokia a few days ago appears not to be true. Some part, perhaps the whole of the Information contained in the “emancipated american,” has I doubt not, been communicated to you by Capt. Lewis, who informed me of his Intention of doing so—For fear it has not I take the liberty of enclosing a newspaper, wherein that piece has been inserted, for your perusal, and of assuring you that, from the best Information I could obtain on the spot, it does not in the least exaggerate the conduct of the late Spanish officers, and that the charges alledged against them, can most, if not all of them be substantiated.41

After meeting with Jones, Lewis asked Stoddard to procure a knowledgeable person to report on the history and production of the lead mines. Stoddard recommended Austin as “the most experienced and judicious man on such subjects then on that quarter.” Austin wrote a dissertation on the lead mines of Upper Louisiana, which accompanied the message sent to the president in November 1804 that was read before Congress.42

After the United States took control of Upper Louisiana, Austin received select appointments and became famous as a mining entrepreneur.43 He was never prosecuted because the extent of his fabrication of land grants was unknown. Jones, too, received lucrative positions in the Indiana territorial legislature. The Jefferson administration also passed a law to limit the number of grants by declaring that no land could be granted after the date of the treaty, which was signed on April 30, 1803.

Although historians have lauded both Austin and Jones as true-blooded Americans, the facts counter this praise and furnish proof that they were the actual conspirators—not the Spanish officers—in a wide-ranging landgrab that preserved the most lucrative, mineral-rich portion of the new territory for themselves.44

When Lewis recommended Austin to Jefferson, Austin was appointed a judge at Sainte Genevieve and, upon publication of the lead mine dissertation, he became an instant celebrity and mining expert. He presided over a kingdom, actually a fiefdom, that was at the center of the “mineral wars” in Sainte Genevieve, where two opposing mining competitors, Moses Austin and John Smith T., battled for land rights from 1804 through 1808.

When Gen. James Wilkinson arrived in Saint Louis in July 1805 as governor of the Louisiana Territory, he tried his best to allay factional spirit, but territorial officials like John Rice Jones, William Carr, and Rufus Easton stood behind Austin while Wilkinson defended Smith T. by unseating Austin as a judge. Party politics escalated, and within the year Wilkinson was ordered to another hot spot in the United States, New Orleans. By 1806, the Austin faction had caused the elimination of five of the top positions in the territorial government—governor, secretary of the territory, territorial judge, attorney general, and a recorder of land titles. It was precisely at this moment that the Lewis and Clark Expedition returned to Saint Louis. A few months later, President Jefferson appointed Lewis governor and Frederick Bates secretary of the territory.

Bates, who had arrived in Saint Louis in April 1807 to take up his duties a year before Lewis's arrival, served as acting governor during that period. Within the first month of arriving in Saint Louis, Bates traveled to Sainte Genevieve and visited Austin. Bates was so enamored with him that he promised to buy a farm in the area, and he appointed Austin's brother a judge as well as electing several of his friends.45

When Lewis arrived in Saint Louis in 1808, he observed the situation of the French-speaking habitants as well as the newly arrived Americans in conjunction with the Americans who had arrived—and prospered greatly—during the Spanish period. There was no doubt that Americans like Austin and Jones had profited from their legacy of having been in the territory before the American purchase and acquiring land under the Spanish, as well as from their later connections with politically powerful Americans who had ensured lucrative government positions, power, and contracts. When Lewis reassessed the recommendations he had made as a newcomer to the territory in 1804, he must have realized that he himself, through his writings, may have set off the mineral wars, and he immediately began dismissing the Austin clan from the bench.

The persons that Lewis appointed to the vacated positions embarrassed Bates and galvanized the Austin forces to thwart Lewis's intentions to bring peace and harmony to the district. Bates, who had faithfully and regularly apprized Lewis of events in Saint Louis up to this point, was angered and appalled by the governor's swift reprisals. In Bates's view, “Affairs look somewhat squally since the arrival of Gov. Lewis. Mighty and extraordinary efforts are making to restore to office some of those worthless men, whom I thought it my duty to remove.” Bates believed that public sentiment had approved of his conduct and that animosity in Sainte Genevieve had subsided. He feared that Lewis's actions reignited the “Demon of Discord,” that “will again mount the whirlwind and direct the storm.”46 In fact, it was Bates who became the demon who secretly allied with Austin to topple the Lewis administration.47

While very little Lewis documentation has been uncovered describing how the Sainte Genevieve mineral wars affected him, he wasted no time asserting his authority by convening the territorial judges and replacing previous appointments made by Indiana territorial governor William Henry Harrison and Bates. Lewis began the formal process of enacting, revising, and passing territorial laws, and in the space of ten months managed to write, authorize, and implement about a hundred of them.48 One law that was immediately passed was meant to curb lawlessness, “regulating riots and unlawful assemblies,” and was directed at Austin and his associates, who had previously menaced others who tried to survey choice mineral tracts near his lands.49 Frederick Bates had appointed John Perry as justice of the peace, but about six months later Governor Lewis revoked his commission:

Complaints of violence and a contempt have lately been exhibited against you, and so conclusively supported, as to render it highly improper, that you should be longer continued in the discharge of public duties. When an Officer acts in direct opposition to the best and principal objects of his appointment, and perseveres in that opposition, after being warned, cautioned & admonished, it is surely time to inform such misguided Officer, that his services are no longer required.50

Lewis replaced Perry with Austin's brother, James Austin.51 That appointment appeared to be a huge blunder, but Lewis had something else in mind. He wanted to corral all of the malcontents, including their leader. Lewis had received depositions from various miners in the area “in relation to a riot” that had recently occurred where members of the Perry family, who were intricately linked to Austin's thugs, were “principally concerned.” Lewis castigated James Austin for permitting it to take place:

It would appear to me, from the evidence which has been transmitted, that it would be the duty of a Justice of the Peace to issue his process for the arrest of the offenders. You will therefore be pleased to review the subject, and compel the execution of your warrant, by the aid of the militia of the neighbourhood, if necessary. The delinquents should be bound in heavy penalties to keep the peace…or…should be committed to jail.52

The Austin thuggery was no match for Lewis's military expertise. The riot had occurred because the rightful owners of the mineral land were prevented from taking the mineral from their property. Lewis asked James Austin to complete an estimate of the lead, which had been gathered on US land adjacent to Moses Austin's tract. Lewis then elaborated via Moses Austin what was in store for James Austin if he did not comply:

After an account has been made of this estimation, you will permit the proper owners, that is, the persons who have dug and raised it, to take it away. And if any resistance be made by any armed force, the militia, are to be called to your assistance, and in the event of a continued forcible opposition, they are hereby ordered to fire on the lawless Banditti, employed in the resistance.53

Surprisingly, the rioting ceased immediately. While Lewis lost the battle in 1804, he later became aware of Austin's deceitful practices and was eventually able to curb them. But Austin still had a confidante implanted in Governor Lewis's office.

President Jefferson and his secretary of the treasury, Albert Gallatin, appointed a committee to oversee the grant process in Saint Louis, a board of commissioners who would make recommendations for confirmation or rejection. Their recommendations brought about congressional legislation and oversight to record, hear, and dispose of all land claims in Louisiana through a series of land boards. The Upper Louisiana board of land commissioners was comprised of five men who presided over the hearings, which began in 1805, and for several years they met at various towns to record claims and testimony. One of the five members was Frederick Bates, who had been appointed in a dual capacity as recorder of land titles and as a land commissioner. Bates could set the pace and direct what land titles would be favored over others.54 The board of commissioners functioned under the US Treasury and received orders from Gallatin himself, but Bates allowed Austin to influence his decisions. Austin wrote to Bates, “I have to tell you that you are to consider & receive what I write as given in strict confidence.” Austin wanted Bates to examine the commissioners’ books and to take such extracts as would answer the intentions of the party. They were to be taken from time to time and in such a way as not to give alarm to the commissioners. It was also hinted that if the extracts could not be obtained in any other way, a friend in court would furnish them.55

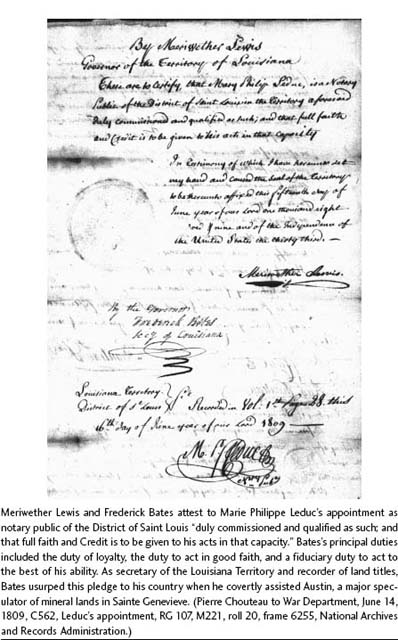

This was an abuse of power, and Bates, who served in three official capacities besides territorial secretary/acting governor, had been entrusted by Gallatin to oversee this important transfer of ownership among the claimants. In that role Bates had principal duties; the duty of loyalty, the duty to act in good faith, and a fiduciary duty to act to the best of his ability. For Moses Austin, the penultimate speculator, to ask for and obtain confidential information created a direct conflict of interest in the execution of Bates's duties.

Bates aided Austin and delayed the confirmation of grants for years. This type of thievery was clearly beyond the scope and governance of Lewis and cannot be associated with the territorial government. The results of the board of commissioners culminated in a decision-making process in 1812 that Gallatin soundly rejected; he “suspended the issuing of patents” to land grants and dismissed the board.56 Divided into a mind-numbing tabulation of forty-nine groups in five classes, the claims took years to resolve.57

During this prolonged delay, the primarily French-speaking claimants were forced into selling their land for a pittance to provide for their families, and as English-speaking settlers moved into the area, they became squatters, and “conflicting land claims led to a large volume of litigation in both state and federal courts” for the next fifty years.58 Confirmation delays deprived the claimants of their land at a crucial time in their lives.

Luke Lawless, a lawyer who defended many land grant suits, took up the cause in court in 1830, stating that the habitants had been assured of their vested rights in the Louisiana Purchase Treaty, which had not been honored, constituting a breach of faith on the part of the United States:

Many of those inhabitants were meritorious servants of the Spanish crown, and had an undoubted right to its future protection. This right, of course, became forfeited by the transfer of their allegiance to the United States, and there then remained…no other fruit of their allegiance to Spain than the grants already made to them…and which they were justified in supposing were virtually confirmed by the treaty under which they became American citizens. It is to be regretted that this reliance on the faith of treaties has not been confirmed by the event. Already twenty years have elapsed, and grants made for services rendered are still unconfirmed. A confirmation at this day cannot repair the mischief and injustice of this long delay; for what can compensate twenty years of human existence wasted in disappointed hope and galling penury? The decree may restore to the injured claimant possession of his lawful property, but it can do no more.59

Without the means to profit from their land to support their families, the claimants were penniless in a new economy that used specie money instead of depending on a barter system. Claimants and officers alike were treated with indifference when it came to having their grants confirmed, and historians have assigned blame to them instead of understanding the core issue:

The great difficulty the land claimants had to contend with, was the imputation of fraud cast upon their claims: the instructions of…Gallatin…appear to have been founded upon a charge of that nature, and show the imperfect knowledge had at that early day.…By those instructions, the whole burden of proof was thrown upon the claimant, and a failure in any one point decided the claims to be surreptitious.…It was further required to show the legal authority of the officer making the grant; this, in no instance, could be done, as the law of the country was the will of the sovereign, known only through the acts of the officer who represented him.60

Austin and Jones were privy to information that they chose not to disclose to Lewis and Stoddard. They instead garnered special attention for being obstructive whistleblowers, and their malicious efforts set about a long and protracted battle for the habitants to acquire titles to their land concessions. The concessions were large, which aided in the belief that the land had been misappropriated, but the rule had been established many years before the Louisiana Purchase because

[t]he small number of the first emigrants to Upper Louisiana, and the warlike character of the surrounding tribes of Indians, compelled the pioneer settlers to establish themselves in villages, and to cultivate but small tracts in their immediate vicinity. Anticipating, at some future day, that their numbers would be sufficient…in extending their settlements, they applied to the authorities and obtained grants for more remote tracts, which they looked upon as the future homes of their families, and some remuneration for the many dangers and privations encountered by them in making their first establishments in the country.61

In 1873, Congress confirmed one of the last Spanish land grants in the old Upper Louisiana district. It had originally belonged to Moses Austin.62