For the past fifty years, historians have utilized a psychological reading of Meriwether Lewis's behavior in an attempt to explain why he missed four hundred days of writing journal entries. They blame him for being lax and lazy, even absent-minded, because he ordered William Clark and several expedition members to write journal entries instead of doing the task himself. Historians believe that Lewis's lethargy contributed to irresponsibility, which prevented him from writing consistently, but new evidence proves the opposite: his duties required multiple entries in other journals. This evidence also suggests that Lewis was not psychologically handicapped, but of sound mind, and that historians have imposed unrealistic expectations and unnecessary demands upon him.

Lewis's responsibilities for the expedition's success originated with President Thomas Jefferson. In his confidential message to Congress in January 1803, Thomas Jefferson announced a bold initiative with the yet-to-be-named Lewis and Clark Expedition. The president had hidden its costs between the paragraphs of a congressional bill that funded the establishment of trading houses near tribal villages. His plan was simple, and he regarded the Missouri River as key to opening the western trade.1 Since 1787 Jefferson had intended to make Alexandria, Virginia, the place of deposit for furs, but George Washington had grander plans and suggested suitable locations further west along the Illinois and Wabash rivers “as the most abundant in furs.”2 In his message, Jefferson framed the expedition in terms of profitability and its usefulness to the public to galvanize Congress into accepting a deeper US trading partnership with Native Americans. And he initially envisioned opening the trade from the Pacific to the Atlantic by employing a unique emissary:

An intelligent officer with ten or twelve chosen men, fit for the enterprize and willing to undertake it, taken from our posts, where they may be spared without inconvenience, might explore the whole line, even to the Western ocean, have conferences with the natives on the subject of commercial intercourse, get admission among them for our traders as others are admitted, agree on convenient deposits for an interchange of articles, and return with the information acquired in the course of two summers.3

This became the template for the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Congress was funding a deft army corps experienced in light scientific training and “for other literary purposes,” to extend the commerce of the nation. Jefferson must have spent some time pondering the wording of the message in order to weave the necessary components of an intricate expedition into it, and at the very end he made one final request to elicit support from congressional members who favored the undertaking.

The interests of commerce place the principal object within the constitutional powers and care of Congress, and that it should incidentally advance the geographical knowledge of our own continent can not but be an additional gratification.4

At the date of his message, Jefferson was also president of an exclusive organization, the American Philosophical Society, which represented American and European scientific-minded individuals who believed in the advancement of the sciences as a literary pursuit. His private secretary, Lewis, was a budding pupil of the society and “incidentally” was “the intelligent officer” who possessed the expertise and ability to accumulate the scientific and geographical aspects of the expedition and to later convert the vast, cumulative data into print.

Congress approved the bill on the final evening of the congressional session, and Lewis departed Washington soon thereafter for Philadelphia to acquire more training on a variety of subjects that would aid him on the expedition. But by the summer of 1803, Lewis realized that the roles of leader and manager of the expedition required the talents of two men and thus invited a longtime friend, William Clark, to be his cocommander. Clark had relevant army experience, which suited him perfectly for the assignment, and when Lewis informed the president, Jefferson excitedly wrote to Henry Dearborn, the secretary of war: “I have the pleasure to inform you that William Clark accepts with great glee the office of going with Capt. Lewis up the Missouri.” Dearborn's reply matched Jefferson's elation. “Mr. W. Clark having consented to accompany Capt. Lewis is highly interesting, ‘N adds very much to the ballance of chances in favour of ultimate success.”5

The Lewis and Clark partnership provided a balanced combination of expertise in scientific matters and in the handling of a group of men. Having approval from the top officers in the nation meant that the division of responsibility was germane to the command. Managing a boat crew, a troop of soldiers, and daily affairs was best left to Clark's prior experience in the army. Clark had joined the army in 1791, and by the time Lewis signed up at Fort Greenville in 1795, Clark had been appointed a lieutenant, commander of his own rifle corps, had fought in the decisive Battle of Fallen Timbers under the leadership of Gen. Anthony Wayne, and had made several important military excursions down the Ohio and the Mississippi.

An important aspect of Clark's military career was having the experience to write journal entries. The details known of his early military career are a result of his written record. Clark was the type of person who understood the necessity of maintaining documentation and duplication of records. A dire requisite of expedition duty entailed a tremendous amount of journal writing maintained principally by Lewis and Clark, but augmented by several other expedition members, too. Lewis implemented redundancy in journal writing because he understood the importance of preservation, diversification, and perspective. In making a trek across the continent into lands unknown to Americans, “amidst a thousand dangers and difficulties” from rampaging animals to possible Indian attack to falling from a cliff or drowning, the expedition's records had to be preserved even if the lives of one, several, or all of the explorers were snuffed out.6 Having several expedition members writing in journals enhanced the chances of success; however, historians have been critical of Lewis in this regard because they believe that he was shirking responsibility and putting undue strain upon William Clark as the principal journalist. That reasoning is based upon unrealistic expectations about what was possible for the success of the expedition.

Jefferson created the template of the expedition and selected Lewis to lead it. He wrote specific goals, which revolved around a scientific and literary model and which comprised four handwritten pages in his typically small writing style.7 The president had placed absolute reliance on Lewis's abilities, and the depth of his range was nothing short of astounding. As far as Jefferson was concerned, Lewis was already a natural scientist who was ordered to use “instruments for ascertaining, by celestial observation, the geography of the country.” He was to “explore the Missouri river…by it's course and communications with the waters of the Pacific ocean…for the purposes of commerce.” He was to take observations of latitude and longitude at the mouth of the Missouri and “especially at the mouths of rivers, at rapids, at islands & other places & objects…that they may with certainty be recognized hereafter.”8

Jefferson devoted a page to describing what was necessary for Lewis to take observations on, a half page to learning about native American commerce and customs, a page concerning soil, vegetable productions, animals of the country (known and unknown), “mineral productions of every kind…more particularly metals… salines” and their temperatures, climate, and thermometer readings. Finally, Jefferson emphasized that Lewis was to find whatever means necessary to deliver “a copy of your journal, notes & observations, of every kind, putting into cipher whatever might do injury” if stolen.9

Lewis secured other pertinent information from members of the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia—in the form of refresher courses in Indian ethnography, botany, zoology, geography, astronomy, ornithology, minerology, meteorology, natural history, and medicine, and he was also given assistance in comprehending and maximizing instrument readings.10 Jefferson placed special emphasis on the need for accurate measurements for longitude and latitude and told Lewis to compare and test those measurements from time to time with others residing in the United States. Today, a complex science centers on celestial navigation and sextant accuracy, and modern-day experts wonder who assisted Lewis in Saint Louis.11

That distinction goes to Capt. Amos Stoddard, who arrived in the Illinois country in June 1803 to assist Lewis and Clark and to oversee the transfer of the country Stoddard's expertise when reading latitude and longitude measurements was outlined in his first report about Upper Louisiana. Destined for a newspaper in the Atlantic states, it was an exacting reflection of the type of reporting specified in the instructions that Jefferson gave to Lewis:

The south boundary of what is called Upper Louisiana, is on the Mississippi, in lat. 36, N. just below the village of New-Madrid, and 75 miles below the mouth of the Ohio. From that boundary to the Shining Mountains or to the sources of the Mississippi and Missouri, is about 2078 miles: and the width of the territory in question, between the Mississippi and the Rio del Nord or North River, is 692 miles. Hence you will perceive, that in Upper Louisiana is contained 1,437, 976 sq. miles, or 920,304,640 acres. It is suggested, however, that the line between North of New Mexico and Louisiana…begins on a ridge of hills near the mouth of the Rio del Nord, in lat. 26, 12, N.; that this ridge extends, parallel to the river, to the source.12

Stoddard had begun writing a book detailing various observations and aspects of Upper Louisiana and expected to publish it the following summer, but by 1806 he still had not completed it. In November of that year, he requested a transfer to Saint Louis because “I have been three years engaged in compiling an account historical and descriptive, of Upper Louisiana—and without a short residence in that territory, I cannot complete it.”13 Six more years were to pass before Stoddard published it.14 Lewis has been criticized for the shortcoming of not publishing the expedition journals within a reasonable time, but completing personal projects was a lengthy process and required much patience when one had other pressing official duties to perform on a daily basis, as governors and military commanders did.

Criticism has also been leveled at Lewis for not making daily journal entries. This criticism was first introduced in 1904 by the historian Reuben Gold Thwaites, who claimed that “[w]hether the missing journal entries (441 days, as compared with Clark; but we may eliminate 41 for the period when he was disabled, thus leaving 400) are still in existence or not is unknown to the present writer.”15 In the present day, historians Gary Moulton and Paul Russell Cutright have taken Lewis to task for saddling Clark with this duty when Lewis should have been writing daily. Moulton says that there were gaps in Lewis's journals that lasted months while Cutright called them “hiatuses” and speculated that Lewis was just plain lazy in not adhering to Jefferson's dictum.16 Moulton said that the gaps in Lewis's journals were numerous and extensive.

They include missing days from the trip on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers from September 19 to November 11, 1803, a nearly complete lapse from May 14, 1804, to April 7, 1805, only spotty entries from August 26, 1805, to January 1, 1806, and a final hiatus from August 12, 1806, to the completion of the expedition. The last gap can be explained by Lewis's being partially disabled from a wound; in contrast to other lapses in writing…. One might also include the period from November 28, 1803, to May 14, 1804, during the winter in the St. Louis area, a time for which no Lewis journal is known. Clark at least kept a rough diary during that time. In all, from May 1804 to September 1806, there are over four hundred days of missing entries by Lewis during the expedition proper.17

Because of the large blocks of missing dates in the daily journals, Moulton and Cutright sidestepped the issue by claiming that there were most likely missing expedition journals. That theory makes sense if Lewis had been an absentminded subordinate who conceivably misplaced or lost the other relevant journals compiled by others on the expedition, but these historians were privy to Lewis's full writing output. They chose not to reveal what Lewis was doing on the days when he was not writing journal accounts on the occurrences of the expedition and the behavior of its individual members. Stephen Ambrose has a completely different view, theorizing that Lewis was depressed, which prevented him from writing daily.18

What these historians ultimately claimed was that Lewis was not as competent as William Clark, and they arrived at this conclusion based on Lewis's mysterious death three years after the expedition. The speculation on the cause of his death and the charge that it was a suicide has led to an avalanche of criticism against him based on the supposition that he was a manic-depressive, addicted to pills and alcohol, and that he ultimately possessed a “flawed character.” In order to prove this theory and support the idea that Lewis was capable of, and indeed predisposed to, suicide, they have to go back through his life, searching for “evidence” in any quirky, strange, or inexplicable episode for the character flaws that they argue led to his downfall. The missing journal entries supply them with evidence for this purpose. According to Moulton, Cutright, and Ambrose, the hiatuses in Lewis's journal-keeping prove that Lewis was deficient and neglectful of his duties as outlined by President Jefferson.

An examination of the dates on which Lewis did not write journal entries, coupled with an outline of what he did accomplish during those periods, will perhaps provide an explanation that will exonerate Lewis from these charges. The gaps in the first group of dates are longer than in the second group, but all the gaps are important nonetheless.19

Moulton explains that these gaps suggest “a larger pattern of negligence.”20 Cutright, an expert on Lewis's naturalistic activities from May 21, 1804, until April 7, 1805, seems to think that Lewis should have been on the boat writing notes that would duplicate Clark's work instead of accumulating and labeling new species of plants. Cutright describes the level of expertise needed to dry and press plants:

The job of pressing plants is not as simple as it sounds, even under optimum conditions of warm, sunshiny weather. Since they contain moisture, they require continued attention until fully dry, which means regular exposure to air and transferring to dry paper for many days running. During the periods when Lewis botanized most actively…he may well have had three or four dozen specimens (or even more) to attend to daily…but there was more to it…. Lewis had to supervise their transport and take every precaution against loss to rain, flash flood, fire.21

Interestingly, the historians do not acknowledge how much time it took Lewis to collect, dry, label, and store the plant specimens. They have essentially graded Lewis within the narrow context of whether or not he took time to make daily journal entries, seeing this activity as being of more importance than all others, and believe that the other time-consuming chores, outlined and ordered by Jefferson, were no excuse for not performing in the area of journal keeping.

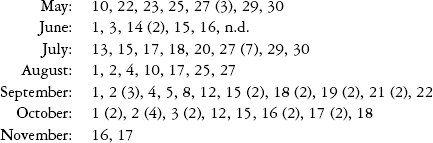

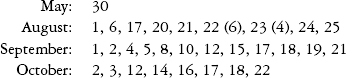

For the entire time of the alleged eleven-month gap of May 21, 1804, to April 7, 1805, Lewis was engaged daily with chores having to do with the collection and preservation of flora and fauna, and working diligently to preserve new specimens and catalogue and label assorted minerals and animal furs. Lewis dated and recorded activities for many days, not in a daily journal but in small books specific to these tasks. For the dates May 21, 1804, through April 7, 1805, there is an alternate or separate amount of data that Lewis collected, per Jefferson's orders, that runs contrary to what historians have claimed. In fact, in the gaps that they cite, they completely ignore the chores and duties that fully occupied his waking hours.22 According to Lewis's botanical collection, he was engaged in scientific work with plant specimens on the following specific days from May through November 1804:23

Ten specimens were undated. The dates that are in parentheses indicate that Lewis found more than one specimen on that day and wrote about it. And, according to Lewis's mineralogical collection, he was engaged on these days as well:24

Close to 119 days of the missing four hundred have been accounted for in this one gap, and this number does not take into consideration all of Lewis's small notebooks. In addition to science, much of his time during the autumn of 1804 was taken up with diplomacy, as the Americans officially notified Missouri River tribes of the change in government from Spain to the United States in official and repetitive ceremonies. The period also involved a week of tense encounters with the Lakota people, which would have disrupted any scientific work.

Lewis also posted a weather diary and charted four conditions every day: state of weather at sunrise and at 4:00 p.m., and the state of the wind and sunrise at 4:00 p.m. He also took regular observations of the sun for navigation, not to mention the failed attempt at coursing the transit of Venus.

Lewis stopped making entries from October 23 until November 16 because Lewis and Clark arrived at the Mandan villages in present-day North Dakota on October 24, 1804, and for the next few weeks they were entertained by the Mandans, gave out medals, delivered talks, and went looking for a suitable spot to build a fort, which was begun on November 4. During the remainder of the month, they saw scores of Mandan and the completion of the fort. Lewis recorded meteorological observations in his “weather diary” for the months of October and November and astronomical observations for three days in November.25 On the thirteenth, Lewis took a pirogue with some of the men to the Mandan village to find stone for chimneys. Six days later, he met with the Hidatsa and returned to the fort on November 27.

By December 7, the weather had turned extremely cold—Lewis recorded 42 degrees below zero on the eighth! With the completion of the fort, they began to think about having to stock it with meat for the winter, and on December 9 Lewis took a detachment of men on a Buffalo hunt. He stayed out all night in the bitter cold. The next morning they were curious about the temperature and Gass recorded that they made a test with “proof spirits,” which “in fifteen minutes froze into hard ice.” Clark also went out in December to hunt buffalo and deer and brought back the meat on sleds.

Once winter set in, Lewis set to work reviewing his notebooks on flora, fauna, mineralogy, and botanicals. During the coldest months he compiled, labeled, and stored a prodigious number of his specimens, readying them for shipment in April to Saint Louis and eventually to Washington.26 Some of the articles shipped on April 5 included 108 botanicals, 68 mineral specimens, 15 skeletons, horns, skins, insects, stuffed birds, and 6 live animals.27

In the month of March 1805, when the night sky was filled to the brim with stars, Lewis took various astronomical readings.28 These readings essentially guided the Lewis and Clark Expedition westward, although historians have separated and minimized these necessary chores from his daily regimen. On April 7, the expedition ventured forth into the unknown, which Lewis confirmed when he wrote in the journal that “we were now about to penetrate a country at least two thousand miles in width, on which the foot of civillized man had never trodden.”29 On his thirty-first birthday, he displayed a wider range of emotions, exposing his introspective side and taking a personal inventory of himself. In his estimation, he “had as yet done but little, very little indeed, to further the hapiness of the human race, or to advance the information of the succeeding generation.” Little did he realize then that the success of the Lewis and Clark Expedition would fill inquiring minds to the present day. He also criticized himself for being indolent, a characterization so contradictory because, as leader of the expedition, he had performed diverse scientific pursuits and had completed them.30

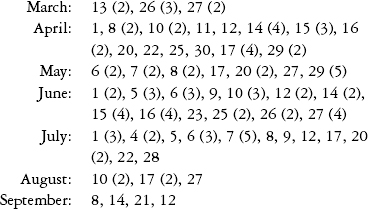

For the years 1805–1806, Lewis continued with his various collections and integrated with his weather diaries the discovery of more plants and the uncovering of a bounty of minerals. For the months from January to November 1805, he found twenty-one more specimens, but in 1806, the western part of the nation afforded many learning opportunities.

These dates bring the number of entries to 136 from January to November 1805 and from March to September 1806, with a grand total from the start of the expedition on May 20, 1804, of 255 notebook entries.

In July 1806, besides summarizing every day and evening with weather and wind specifications, he also jotted down other information apart from the discoveries. On July 1 he reported “a species of wild clover with a small leaf just in blume.” Two days later, he wrote about turtle dove eggs, and on July 5, after recording the temperature, he described pigeons and how cold the temperature had become.

Perusing this new data has exposed a new trait: Lewis was a chatty diarist! In fact, when examining these weather diaries a new side to his personality emerges. Lewis took the utmost care with his observations and injected a literary aspect/component to them. On July 8, he wrote that in the morning a heavy white frost blanketed their camp and that it was very cold the night before. He wrote specialized information in the weather diary for these days: July 1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 16, 17, 23, 24, 25, 26, 28, 29, 30, 31.31

In July 1806, Lewis and Clark headed in two different directions. Lewis led a group to the Marais River looking for its northern reach, but on August 11, Pierre Cruzatte, an expedition member, accidentally shot Lewis, mistaking him for an elk in the bush. Despite the severe injury and having to lay face down in a boat, Lewis's writing output did not suffer; he assembled a weather table on August 12 and continued making weather observations until the end of the month.32 Taking into account all of his weather diaries and notes from October 1805 through August 1806, Lewis wrote about 270 descriptions, which greatly exceeds the “400 missing journal entries.”33

One strategic piece of information that the critics fail to address is that the expedition was mounted for several purposes, and that Lewis, as commander, could delegate tasks and make decisions about who did what type of work and who kept what types of journals. He divided the tasks of managing science and managing men between the commanders, and this could be extended to the type of journal kept by each. Clark's journals contain some scientific information, but are mostly, let's face it, the adventure narrative; they are more akin to military orderly books than scientific journals. All of these experiments and duties kept Lewis busy with the scientific portion of the trek, but we can't ignore that his diplomatic responsibilities with the Indians were an important distraction as well.

The question is not so much why he didn't keep a diary like Clark's as a duplicate, but rather why, on those days when he did so, did he keep a diary at all? If it was for the duplication, then why weren't the scientific records themselves in the separate little notebooks duplicated, and, indeed, why were they scattered in individual notebooks in the first place?

The loss of items like the answers to the Indian queries posed by Dr. Benjamin Rush could have been avoided if these things had been duplicated or if they had been copied into journal books. The loss of the plant and animal specimens and information was every bit as important as the potential loss of the narrative of the trek. Even enlisted men on the expedition who were literate could have been detailed to do the monk-like copy work necessary to ensure duplication of scientific and/or narrative journals, at places like Fort Mandan and Fort Clatsop, but this was not done. Have modern scholars merely jumped to the conclusion that Lewis tried to follow Jefferson's order about duplication? Or was the effort needed for such duplication just too overwhelming in the overall scheme of making the expedition a success?

Questions about Lewis's role on the expedition will hopefully swing the other way now that the puzzling weight of the missing journal entries has been solved, and the need to inquire further into Lewis's supposed recording gaps has come to an end. He was actively engaged in the enterprise of collecting and collating his discoveries, one of the major purposes of the expedition. In light of this newer research, the time has come both to review his participation in the colossal undertaking of gathering new specimens for science and to give him the credit that he deserves.