One of the exciting things about conducting historical research is that on almost any topic one chooses to investigate there is always the possibility of the discovery of new information. This information can take many forms. It might lie in associated or even previously unrelated manuscripts or records that make reference to the same events or individuals one is studying. Even more exciting is the occasional discovery of a previously unknown, misplaced, or overlooked manuscript relating directly to the subject matter of the historian's investigation. During the many years of exhaustive research needed to prepare for my recent biography of Meriwether Lewis, I ran across many such pieces of information. One would think, after two hundred years and the close scrutiny of so many authors, researchers, and historians, that the bones of the Lewis and Clark story's skeleton would be picked pretty clean. However, this is not the case, and there may be even more material still buried in voluminous archives, libraries, and attics yet to be discovered.

The subject of this chapter, in fact, is a letter that was hidden in plain sight within one of the best-known collections in the world—the National Archives in Washington, DC. One of the essential sources for the Lewis biography was the examination of surviving military records of the period. Short of purchasing all of the microfilm necessary for a thorough look at these records, I decided in November 1998 to visit the National Archives, Central Plains Region Branch, in Kansas City, Missouri, which had a complete set. After two days of examination (punctuated by giving up my seat every half hour to genealogists), I photocopied about three hundred pages, but after returning home and reading through the material, I found that I had not secured all that I needed. I realized then that it was foolhardy to waste so much time driving across the state of Missouri, staying in a hotel, using timed microfilm readers, and then paying for photocopies.

From the letters that I read in several reference works, like the Territorial Papers, I realized that a serious study of Lewis warranted the purchase of the necessary microfilm, both for initial research and for later reference. The National Archives published a microfilm resource catalog, which was helpful in determining what to buy.1 The guide did not indicate specific locations of any individual Lewis letters—it was just a microfilm guide of the governmental record groups listed by year.

Clarence Carter, editor of the Territorial Papers, cited numerous documents in the National Archives as references, so it appeared that his footnotes could be followed on the microfilm rolls; however, it was not that easy. While the documents were located on the microfilm, more often than not, they were out of sequence by date. That meant that instead of using the fast forward or reverse button on the microfilm reader to speed through the process, I would have to turn the microfilm roll by hand and painstakingly look at each frame. At first I was annoyed at the glacial pace of this type of investigation, but when I began to discover new or at least unheralded documents, my mood began to change. In the very first batch of microfilm that I received, I found an 1808 letter from Denis Fitzhugh to James Madison, forwarding a bill of exchange from Lewis for $500, which had been allocated for Joseph Charless's printing press in Saint Louis.2

By 2004, I had amassed an extensive library of National Archives microfilm. I had also implemented a new personal standard for advancing a microfilm roll—with my index finger, frame by frame. As each day passed and I continued to discover a cornucopia of new information, I grew increasingly anxious about how I was going to be able to remember, much less find, where all the facts were stored—in notebooks, photocopies, and other primary and secondary sources. The scale of the research was becoming enormous.

The old stand-by index card method, or the newer method of placing categorized notes in a word processing file, were both unsatisfactory. As I was lamenting to a friend the way in which I was slowly becoming immobilized and overwhelmed by huge amounts of information, she suggested a novel method—to use a spreadsheet to create a database completely searchable by columns. It took nine months to enter the microfilm information into eight columns of data, which eventually totaled 3,600 entries. Despite the enormous amount of time and effort it took to create it, I found this database to be highly efficient when trying to locate tiny pieces of strategic information or just helpful in following the history of a given topic. Additionally, the database made it easy to copy the exacting endnotes that are the foundation of this chapter, the Lewis biography, and the rest of this book.3

Carter incorrectly cited some important letters and other historians copied his mistakes, so inspecting the microfilm became a mandatory exercise that eventually led to the discovery of the Lewis letter featured in this chapter.4 On February 18, 2003, I had received two rolls of National Archives microfilm from the M222 series. The descriptive pamphlet for this microfilm stated, “On the 34 rolls of this microfilm…are reproduced letters, with their enclosures, that were received by the Secretary of War…but, for one reason or another, not registered.” The pamphlet writer continued, “The letters are arranged by year and thereunder alphabetically—most by the initial letter of the surname of the officer, but a few by the initial letter of the subject.”5

Placing roll 2 on the spindle, I began to advance it slowly.6 Categories from A to K held nothing of importance for the biography, but at frame 0555–58 under the letter “L,” there was a listing for “Expenditures in Capt. M. Lewis Expedition to April 1805.” At frame 0571, a Capt. Bruff wrote Gen. James Wilkinson that he had succumbed to the ague (malaria) and could not report for some time. At frame 0657, Lewis addressed Henry Dearborn, the secretary of war, in a letter dated October 1806 at Saint Louis, apologizing for signing a large number of drafts. This section of the microfilm details much business concerning expedition members and some supplies.7

The following day I reached frame 0772. William Clark had written on May 9, 1807, about his participation in a treaty and council with the Yankton and Teton nations. At frame 0974 Rodolphe Tillier, the factor at Bellefontaine, wrote that illicit traders were telling various Indian nations that Spain would regain Louisiana and expel the Americans.

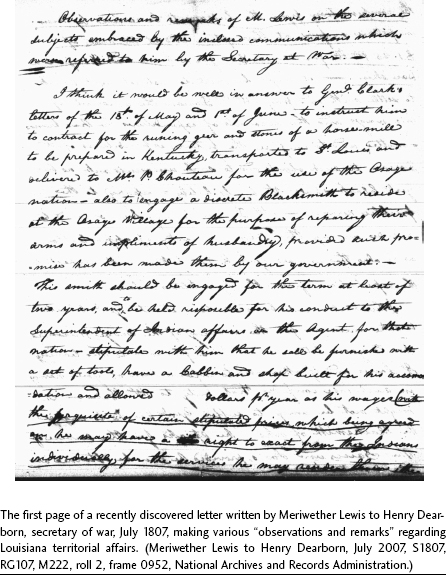

Reaching the end of the reel, I started to rewind the film by hand. At frame 0952 I noticed something peculiar under the “S” category, which stood for “secretary of war.” The letters were from officers in the field detailing expenditures or asking for monetary relief. One letter did not have a date. I continued backing up the reel, but stopped and thought to myself, that letter looks like Lewis's handwriting. When I returned to the frame, I was surprised. It was indeed a letter from Lewis, and one that I had never before seen.

[page 1] Observations and remarks of M. Lewis on the several subjects embraced By the inclosed communications which were referred to him by the Secretary at War.—I think it would be well in answer to Genl. Clark's letters of the 18th of May and 1 st of June—to instruct him to contract for the runing gear and stones of a horse-mill to be prepared in Kentucky, transported to St. Louis and delivered to Mr. P. Chouteau for the use of the Osage nation—also to engage a discrete Blacksmith to reside at the Osage Village for the purpose of reparing their arms and impliments of husbandry, provided such promises has been made them by our government.—

This smith should be engaged for the term at least of two years, and to be held risposible for his conduct to the Superintendent of Indian affairs as the Agent for that nation—stipulate with him that he sall be furnished with a set of tools, have a Cabbin and shop built for his accomodation and allowed dollars per year as his wages (with this perquisite of certain stipulated prices which being agreed on he may have a right to exact from the Indians individually for the services he may render them either [page 2] the compensation from the Indians to be received by him in peltries or fur at their option and at the rate of $1.25 per lb. for beaver $2—for a buck and $1 for a doe skin.—it might be well to instruct Genl. Clark to settle with and pay Mr. P. Dorion the amount of his wages and the accounts of expenditures he has transmitted, and to confine the future expenditures of Mr. Dorion to such objects and to such amounts only as he, Genl. Clark shall think absolutely necessary to the public service—Mr. Dorion having been ordered to reside among the Tetons is worthy of approbation, as is also the course Genl. C. has taken with rispect to the deputation from the Yanktons & Tetons—.

I think it would be well to instruct Genl. Clark to take measures for the recovery of the Osage prisoners, should your letter reach him previous to his leaving St. Louis and if otherwise to inform him of your having in such case confided that duty to Mr. Bates—it might not be amiss to suffer Genl. Clark to engage the blacksmith of whom he speaks for the service of the Saucs and Foxes, provided he can be obtained on moderate terms.—

[page 3] In answer to Mr. Bates's letter of the 15th of May, it would be well to inform him that Govr. Harrison had been instructed to make every exertion to recover the Osage prisoners in his territory, and request of Mr. Bates, in the event of Genl. Clark not being at St. Louis, to use his exertion for the same purpose among the Indians of Louisiana—inform him also that Genl. Clark had been instructed to contract (furnish) for the Horsemill which had been provided the Osage—on the subject of the Horse-mill and Blacksmith that have been promised the Osages.—

I think it would also be well to instruct Mr. Chouteau to make compensation to the Osage for the horses which were purchased from them by Lieut. Pike and Wilkinson—to inform him of the measures taken in order with a view to provide the Horse-mill and Smith for the Osages and request him to communicate this information to that nation in order to satisfy them for the present—inform him of the measures taken relative to the Osage prisoners, and request that also to be communicated to them.

[page 4] It will be necessary to write to Govr. Harrison fully on the subject of the Osage prisoners. I am convinced that it is much more in his power to obtain them than any other…officer in that quarter, as it becomes more immediately his duty as those prisoners are among the nations in his territory—as a matter of general policy it appears to me that it would be well to mention to Mr. Bates, Genl.Clark and Govr. Harrison on the subject of recovering these prisoners, that nothing should be given to the individuals preparing them for their delivery, and that it would be better to give double the amount to the chiefs of some of their more powerfull neighbours to compell their delivery than to redeem them by purchase from their owners.

—M. Lewis

Titled “Observations and Remarks,” Lewis's letter was written at the end of July 1807 to Henry Dearborn, who was not in Washington at the time.8 Lewis's letter consisted of a lengthy answer to many questions on Indian relations and Indian trade posed by Dearborn in referencing two letters from William Clark (dated May 18 and June 1, which were received at the War Department on June 29 and July 7) and a letter from Frederick Bates, the acting governor (dated May 15 and received on June 29).9 Dearborn either forwarded the original letters to Lewis along with his own queries, or had the Clark and Bates letters transcribed and enclosed so that Lewis could read them. In reading all of these letters it must be borne in mind that Lewis was at the time the governor of the Louisiana Territory, even though he had not as yet returned to Saint Louis to take up these duties full time.10

We know from other sources that at the time that Lewis answered the Dearborn letter, he had recently traveled from Philadelphia to Washington. Lewis departed Philadelphia on July 21 and arrived in Washington a few days before a meeting with William Simmons, the accountant of the War Department.11 We do not know if Lewis took a night coach, which would have taken two days from Philadelphia, or rode a horse, which would have taken four more days to reach Washington.12

Interestingly, Lewis was not idle in Philadelphia from the time of his arrival on April 14 until his departure three months later, as some historians have claimed. Lewis employed individuals to draw botanical illustrations and scenery for the publication of the journals, met with publishers and printers, paid newspapers to run his ad for the journals, began editing the journals, and prepared additional material for another volume. He also attended three meetings at the American Philosophical Society, having become a member in November 1803.13

In light of this new letter, I believe that he also was writing his treatise on the business of Indian trade in the Louisiana Territory titled “Observations and Reflections,” which when complete numbered twenty typed pages. Donald Jackson, editor of Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, contended that Lewis wrote the greater part of this treatise before he departed Washington in August 1807. This letter proves that Jackson was correct.14

The letter itself is clearly thought out, pragmatic, lucid in its detail, and refers to specific topics that involved William Clark, Pierre Chouteau, and the Indian agency Clark's letters of May 18 and June 1, to which Lewis was responding, brimmed with territorial business.15 Foremost on Clark's agenda were the frequent visits of various Indian nations and how to deal with them. Since Spanish colonial times, Indian tribes had arrived in Saint Louis asking for gifts of food, clothing, and shelter. Nothing in this respect had changed, although Jefferson had conveyed to Lewis, when on the expedition, that he should invite as many tribes to Washington as he saw fit. Soon the news of the Indian delegations led by Pierre Chouteau, Amos Stoddard, and others made its way back to the Louisiana Territory, and the leaders of Indian nations heard that the “Great White Father,” in Washington was generous indeed.16 This prompted a huge influx of Osage Indians into the town of Saint Louis. Clark's May 18, 1807, letter stated that “[t]he Great Chief and about 120 Osarge [sic] Warriors left this place three days ago; they were here for some time.”17

Clark's letter opened by stating that he had made arrangements since his arrival in Saint Louis “to send the Mandan chief to his Town in Safty.” Dearborn had instructed him to use no more than sixteen soldiers because there were few remaining in Saint Louis, and barring that, Clark could entice traders going up the Missouri River with exclusive licenses. This is exactly the strategy that Lewis employed a year later.18 Under this arrangement, Clark obtained an additional escort from a private trading outfit and also a returning delegation of Sioux Indians. Clark feared that the Arikara might prove hostile to the group and felt that the larger party, about 101 adults, would help to deter them. Two other large companies of traders and trappers set out from Saint Louis on May 1, intending to trap in the Rocky Mountain area for a period of two to three years. A smaller outfit also departed Saint Louis in March; historian John C. Jackson believes that it was led by John B. Thompson, who was bringing supplies upriver to John Colter. Thompson and Colter were members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

Clark also spoke in detail in his letters about various Osage complaints, the most prominent being that they had been promised that a mill would be built at their village and that a blacksmith would reside with them. These complaints were not to be taken lightly, as the Osage were the most powerful tribe on the lower Missouri River and a potential American ally. The tribal leaders also complained that James Wilkinson, son of Gen. James Wilkinson, took seven horses and promised to pay for them, which had not been done.19 Indian nations from the eastern side of the Mississippi had taken some Osage prisoners and had returned only a few.

Clark informed Dearborn that a Sauk had murdered a Frenchman at the mouth of the Missouri. He had dispatched Nicholas Boilvin to the Sauk nation to demand that the chiefs deliver the murderer. To the west the Spaniards had assembled an Indian conference and informed the nations that the Americans were untrustworthy. From the north came word that the British had formed a new trading company with Montreal traders to encompass the entire fur commerce of the region. Clark believed that the new company could injure the trade that the United States was trying to establish. The furs and peltries would fall into the hands of the British and various Indian nations and local Creole merchants would be deprived of the means of supporting their families.

Pierre Dorion, an Indian subagent, showed up in Saint Louis with a large band of Sioux who had been invited to visit the president in Washington. Clark had no instructions on the subject of these sudden appearances of Indian tribes and wanted Dearborn to enact some policy to guide him in the future. Clark did not want to reject the Indian tribes because their friendship was important to the stability of the region. He decided to give them about $1,500 worth of presents, which would “give their bands an exolted opinion of the Paternal affection of the President to all the Nativs who seek his protection.”20 Dorion had not been paid since Gen. Wilkinson appointed him to his official position in 1805 and demanded that Clark pay him. While Clark refused, he felt the necessity of giving the Sioux the presents. Having resided with the Sioux for close to thirty years, however, Dorion's influence in keeping the Sioux at peace was paramount. Clark asked Dearborn for additional money so that he could pay Dorion. Clark closed the letter by stating that the militia of the territory, as well as their arms and ammunition, were deficient.21

Clark also sent Dearborn a letter dated June 1, 1807, which was almost a repetition of the May 18 letter. Boilvin had returned from the Sauk nation without the murderer but was promised him in due time. A Mr. Ewing, who had been sent to the Sauks in May 1804 to teach them farming, had been recalled, and it was Clark's job to inform him. The Sauks also wanted a blacksmith, and a Saint Louis farmer had offered his services.

Bates's letter of May 15 did not add any new information, but one can discern that he did not want to become involved in the Indian business.22 While that was his intention three months into his tenure as territorial secretary, he also believed in free trade for American citizens. When Clark departed Saint Louis in August 1807, Bates began issuing licenses to trade without restriction.23

In response to Clark's letters concerning the Indian business, Lewis was on point. He laid out detailed answers and told Dearborn what should be done. His answers regarding Dorion, the blacksmiths, Governor Harrison, and Bates's role after Clark's departure show that Lewis was in command of the Indian business. On August 18, 1807, Henry Dearborn copied Lewis's words almost verbatim to Clark and Bates, reminding us that Lewis was held in great esteem even at the highest levels of government.24

This newly identified Lewis letter affords us a glimpse of the man during a period in mid-1807 from which we have little surviving written evidence. This lack of information has caused some rather wild speculation by some biographers, imagining Lewis reveling in a life of at most debauchery, or at least indolence, during a period when he was expected to travel to Saint Louis to take up his duties as territorial governor. The letter shows Lewis exercising his duties as governor in absentia, answering crucial questions regarding the territory and the future of the United States on the frontier that could not be addressed by Clark, Bates, or Dearborn. The letter presents a picture of a clearheaded administrator delayed in the east by duties other than those of his post, but one who would be quite ready to assume those duties upon his arrival in Saint Louis.

There may be other letters still out there, undiscovered or unrecognized, that will provide more insight into the Lewis and Clark story. Just as we should go through microfilm frame by frame, the discovery of these letters, if they exist, will also be a slow and painstaking process, but a highly rewarding one for scholars and enthusiasts.