Looking back in time, we often are able to identify the mistakes of our predecessors. When the Corps of Discovery returned from its epic journey, Congress bestowed upon each member a tract of land in the Louisiana Territory. Although a seemingly benevolent and well-deserved gift, it was impossible for any member of the corps to benefit from this land gratuity because very little of the Louisiana Purchase had been surveyed and none of the acreage had been plotted on a map to differentiate private from public land.

On January 2, 1807, a congressional committee convened to assess the compensation for Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and “their brave companions for their late service in exploring the western waters.”1 Willis Alston, chairman of the committee, asked Secretary of War Henry Dearborn for a roster of the men, which Lewis provided on January 15. Dearborn proposed double pay for each member of the Corps of Discovery, a grant of 320 acres to each of the thirty-one enlisted members, 1,000 acres to Lt. Clark, 1,500 acres to Capt. Lewis, “and that each one should have permission to locate his grant on any lands that have been surveyed, and are now for sale.”2 Lewis was emphatic that no distinction of rank be made between him and Clark, preferring “an equal division of whatever quantity might be granted to them.”3

The House deliberated on the bill for several weeks, and on February 20, a heated discussion followed:

The bill grants land warrants, which may be either located or received at the land offices in payment of debts due there, at the rate of two dollars an acre. The bill grants these persons 24,960 acres. A motion was made…to strike out so much as permits the receipt of these warrants at the land offices in payment of debts.…It was contended that double pay was a liberal compensation, and that this grant was extravagant and beyond all former precedent. It was equivalent to taking more than $60,000 out of the Treasury, and might be perhaps three or four times that sum, as the grantees might go over all the Western country and locate their warrants on the best land, in 160 acre lots.4

The House of Representatives recommitted the bill eight days later and sent it to the Senate, where it was revised and approved on March 3. Lewis and Clark each were granted 1,600 acres, the enlisted men were given 320 acres each, and the grants could be located only on the public lands west of the Mississippi. Double pay was authorized for all.5 The grant came in the form of a certificate known as a land warrant, which was an authorization to receive a quantity of public land at an unspecified location. The actual selection of a tract of land lay more than a decade in the future.

At the time of the reward, public land on the east side of the Mississippi sold for two dollars an acre, while on the west side of the river, public land essentially was worthless. This was because public land had not been surveyed, and until boundaries separated the public from the private land, the public land could not be sold. The first appointment of a US surveyor in the Louisiana Territory occurred in July 1806, but the business of surveying the territory languished until 1816 due to insufficient manpower and Native American hostilities.6

Corps of Discovery members who remained in or returned to Saint Louis after the expedition could do nothing with their 320-acre warrants. In November 1808, Territorial Secretary Frederick Bates bought land warrants for about $300 each from seven members of the expedition: John Collins, George Drouillard, Patrick Gass, Hugh McNeal, John B. Thompson, Joseph Whitehouse, and Alexander Willard. Bates ran an ad in the Missouri Gazette at the end of March 1809 to sell two warrants and in August, attorney William Carr exchanged a slave for one warrant and was delighted with the deal.7

That same month, Lewis and Clark were forced to sell their land warrants. In March 1809, Clark paid for two shares in the Missouri Fur Company and Lewis advanced payments to take Mandan chief Sheheke-shote home. Three months later, the War Department sent letters with refusals to pay Clark's expenses related to the Indian agency and Lewis's for Indian presents. That left Lewis and Clark in a fiscally tight and embarrassing situation, and they turned to their land warrants to bridge this economic shortfall. Lewis decided to tender the warrants at the land office in New Orleans and that may have been the initial reason why he intended to travel there.8

Lewis left Saint Louis on September 4, 1809, and arrived at Fort Pickering terribly ill eleven days later. As Lewis recovered over the course of nearly two weeks, he switched plans and decided to travel on horseback to Washington. On September 17, Lewis wrote about the warrant in his account book:

Then enclosed my warrant for 1600 acres to Bomby Robertson of New Orleans to be disposed…for two dollars per acre or more if it can be obtained and the money…deposited in the branch bank of New Orleans or the City of Washington subject to my order or that of William D. Meriwether for the benefit of my creditors.9

Capt. Gilbert Russell, the commander at Fort Pickering, stated that at Lewis's request, he sent Lewis's land warrant to Thomas Bolling Robertson, secretary of the Orleans Territory and a land commissioner. Lewis hoped that Robertson would be able to sell the warrant, but it was returned due to insufficient cash.10

Lewis's warrant remained with his mother for a dozen years. Members of the expedition who did not settle in the Louisiana Territory, but rather resided in adjacent territories in Alabama and Mississippi, were able to assign and redeem land for their warrants.11

In 1821, the Lewis family hired a Richard Searcy as its agent to facilitate selling the warrant, but he ran into many obstacles. In 1826, Searcy explained the difficulty to the commissioner of the General Land Office:

I have heretofore informed you that I was the holder of the warrant to the late Governor M. Lewis for his western tour…. This warrant was placed in my hand for the purpose of being sold…which I have been endeavoring to do for the last five years, but owing to the inconvenient size of the warrant and other causes I have yet been unable to make any disposition of it. Besides the refusal of the Commissioner of the General Land Office to issue certificates in smaller amounts which would have facilitated its sale the land officers here have been reluctant at having any thing to do with the claim…the receiver of Public Monies at Little Rock refused to receive it at more than $1.25 an acre…notwithstanding the letter of your predecessor…directing it to be received at $2.00 an acre. From the above causes the representatives of Govr. Lewis have already suffered considerable loss by being so long kept out of the value of the warrant. The claim has repeatedly been offered for sale at from 10 to 20 percent discount and more…. This warrant was granted to a meritorious officer for valuable services rendered to his country.12

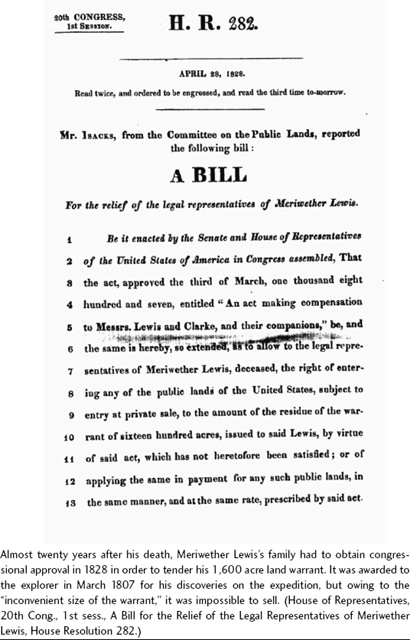

Searcy received no satisfaction. The following year, the Lewis family pressed Congress to intervene, and on April 28, 1828, the Committee on Public Lands reported a bill “for the relief of the legal representatives of Meriwether Lewis,” which asked that Congress allow Lewis's legal representatives

the right of entering any of the public lands of the United States, subject to entry at private sale, to the amount of the residue of the warrant of sixteen hundred acres…which has not heretofore been satisfied.13

Congress finally approved the bill on May 26, 1828.

Lewis eventually was reimbursed for his public service, and his family enjoyed a fleeting glory. It is tragic that he never shared in the realization of 1,600 acres of the immense wilderness that he explored and set on the way to development.