In an age where computers and cell phones carry instantaneous messages around the world and overnight shipments of letters, parcels, and goods are fairly cheap and commonplace, it is difficult to imagine a time when correspondence between some of the major cities of the United States took months rather than seconds. Even the vital correspondence of a frontier governor like Meriwether Lewis was subject to the same difficulties of transport as the mail for any person living in the mid-Mississippi River Valley. The following information is centered on proving that some of Lewis's mail, specifically correspondence that included monetary instruments, appears to have been intentionally delayed and perhaps tampered with. While the identities of certain individuals who had access to the mail is known, modern historical detective work has yet to uncover the culprit or culprits, leaving this a fascinating story that, at least for the time being, has no real conclusion.

When Saint Louisans sent correspondence to officials in Washington, DC, the mail took about thirty-eight days to reach the capital. Surprisingly, when Governor Lewis included monetary instruments in his correspondence, like a draft or a bill of exchange, delivery took more than twice that time. Drafts and bills of exchange were two different monetary instruments during Lewis's time, while today the terms have the same meaning. What they knew as a “draft” appeared to have ready value and was used much like a check today, but in Saint Louis, where specie money was scarce, the value was exchanged in goods. A “bill of exchange” only had ready value after it was sent to the government for approval and reimbursement.

In order to explore the mystery of Lewis's delayed mail, it will first be essential to understand how the mail was collected and transported in the early nineteenth century. There were two collection points on the west side of the Mississippi, one at Saint Louis and the other at Fort Bellefontaine eighteen miles to the north. The mail from the fort was carried to Saint Louis, then taken by boat across the Mississippi and deposited with the Cahokia postmaster in the then-Indiana Territory (today's State of Illinois). From Cahokia, post riders formally carried the mail over the post roads to Washington. The use of the term “road” is a loose one, as many of these routes were merely glorified paths. No system of highway maintenance or construction was yet in place west of the Appalachians, and road maintenance in western Virginia and Maryland was rudimentary at best. Arduous routes included river crossings, many without bridges or ferries, and passage through the mountains. In 1804, delivery time from Saint Louis to Washington, DC, averaged about a month, yet was dependent on weather conditions. Winter in the wilderness was hazardous and spring rains made traveling treacherous due to flooding. The opportune time for the regular delivery of mail occurred before the temperature dropped below freezing and after the spring rains.

Post riders carried the mail in special leather saddle-bags that were locked with keys that only postmasters possessed. Delaying a post rider or tampering with the mail was a Federal offense. Riders had to endure severe extremes of temperature and weather as they rode their routes, relaying the mail from one rider to the next between individual post offices as the mail slowly worked its way from one town to the next. These mail riders, although perhaps spiritual kin to the Pony Express riders of fifty years later, were unlike the Pony Express in that there was no time constraint or record to beat; they were only obligated to do their best to move the mail in a timely and efficient manner on to the next post office and one step closer to its ultimate destination.

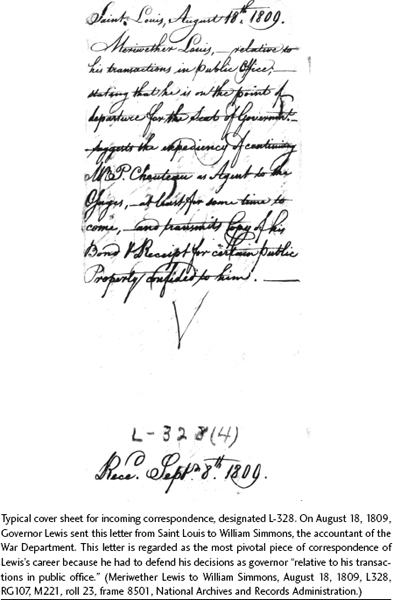

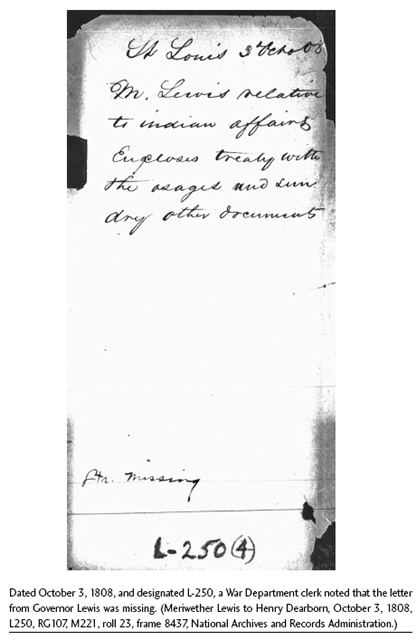

Once the mail arrived at the capital, it was taken to a central government post office, where a clerk recorded it in a ledger, assigning each piece of mail a document number, alphabetically by surname of the sender, and numerically in the order of its receipt. For example, when one of Governor Lewis's letters arrived in Washington on September 8, 1809, it was given the document number L-328: L for Lewis and 328 for the 328th piece of mail with that surname letter designation that had arrived in that year.1 The number was not sequential for each piece of mail received by the government for a calendar year, nor was it sequential for each piece of mail received from an individual sender, but instead was sequential for each piece of mail for a specific letter designation. The clerk then briefly described the contents of the letter and its point of origin. Before sending it to the proper department, the clerk then wrapped it in a cover sheet, on which he wrote the date, a thorough explanation of its contents, the number of the document, and when it was disbursed by the clerk to the proper official.2

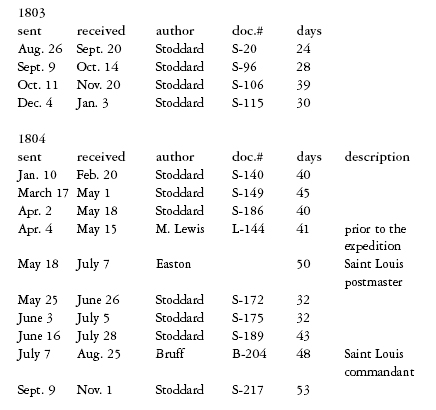

Mail delivery increased dramatically with the transfer of the administration of the Louisiana Territory from France to the United States and the need for an increased number of Federal officials to govern this vast land. This process started six months before the transfer of the Louisiana Territory with the arrival of Capt. Amos Stoddard in Kaskaskia to begin his tenure as territorial commandant. The transfer of the territory occurred on March 10, 1804. In October of that year, the postmaster general appointed Rufus Easton, a lawyer from upstate New York, who had already arrived in Saint Louis, as Saint Louis postmaster.3 From August 1803 to September 1804, the average time for official letters to reach Washington was thirty-nine days.

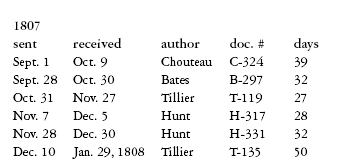

In July 1805, when Gen. James Wilkinson arrived in the territory as governor, there were clashes with the habitants, immigrating Americans, expatriated Americans, and Saint Louis officials regarding territorial policy. It is reasonable to assume that these conflicts might contribute to a lengthening of the time for mail delivery to Washington, and yet they did not. On January 6, 1806, Gen. Wilkinson wrote five letters to the War Department, which arrived on February 20, and on January 7 and 8, he wrote two more, which also arrived on February 20, suggesting that mail went out once a week.4 The average transit time for the recorded official territorial correspondence of 1806 to reach Washington was thirty-seven days, except for letters dated February 10 and August 15 by Pierre Chouteau, the Osage Indian agent, which took much longer.

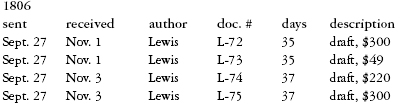

The Lewis and Clark Expedition arrived at Fort Bellefontaine after their voyage of discovery on September 21, 1806, and two days later returned to Saint Louis. Capt. Lewis began discharging the men and also sent five letters to Washington with drafts ranging from $49 to $300. These letters took between thirty-five and forty-five days to reach Washington.

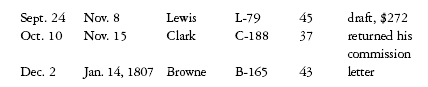

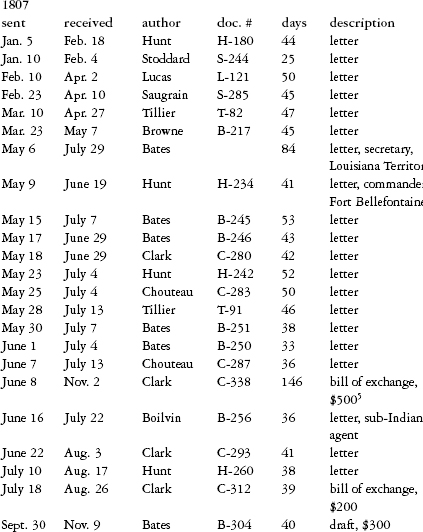

In 1807, the delivery time of letters mailed between January 5 and March 23 averaged forty-three days, but when William Clark arrived in Saint Louis as Indian agent for the territory, he included a bill of exchange in his June 8 letter, which took five months to arrive in Washington.

When Clark departed Saint Louis at the end of July 1807 to wed Julia Hancock, the arrival time of the mail became regular once again.6

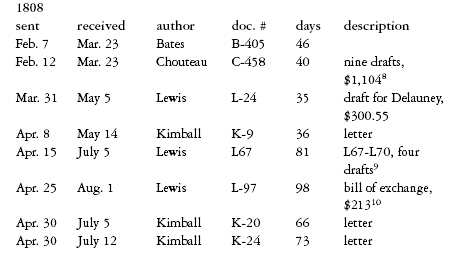

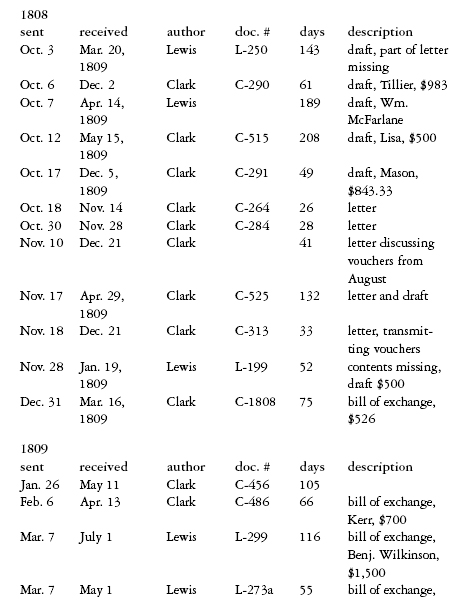

Lewis arrived in Saint Louis on March 8, 1808, and the delivery of his mail lagged far behind mail sent by others, especially letters Lewis posted that included monetary instruments.7 The letters dated April 15 and April 25 took eighty-one and ninety-eight days, respectively, to make the journey.

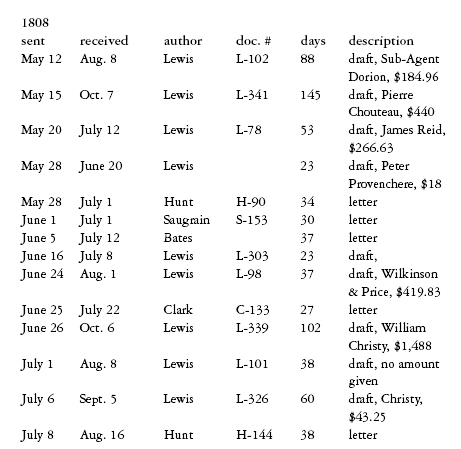

Lewis had been in Saint Louis a little more than two months when the pattern of delayed delivery began to increase. Of the nine letters written by Lewis between May 12 and July 8, 1808, which included drafts, five took greater than fifty days between posting and delivery.

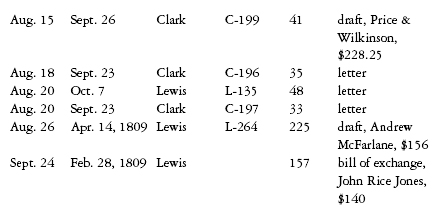

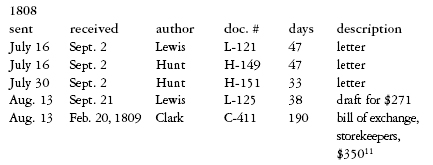

Two letters with bills, one from Clark dated August 13, 1808, and the other from Lewis dated August 26, 1808, deviated from the regular pattern with transit times of 190 and 225 days, respectively. Delayed payments could easily strap the sender financially, since the sender was advancing payment to others using his own personal credit.

A disconnect between correspondence and payments affected them. Between October 6 and December 31, 1808, five Clark letters containing drafts or bills of exchange took an average of 105 days to reach Washington. Clark raised concerns over the issue in a letter to the secretary of war in November 1808 when he mentioned previously sent vouchers: “please to inform me if you have received the public vouchers which I sent from this place last August. The distance and uncertainty of the mail, created some anxiety on this subject.”12

Three 1808 Lewis letters with vouchers in them took an average of 128 days for the journey. When Lewis's November 28 letter arrived in Washington, the contents were missing. It was a draft for $500 that was to be taken from the governor's salary.13 That meant that Lewis had already allowed the payee to debit his account at a store. In this particular case, Lewis did not become aware of the missing contents for at least six months. The store sent in a voucher for payment, and the clerk in the accountant's office held the voucher waiting for Lewis's draft.

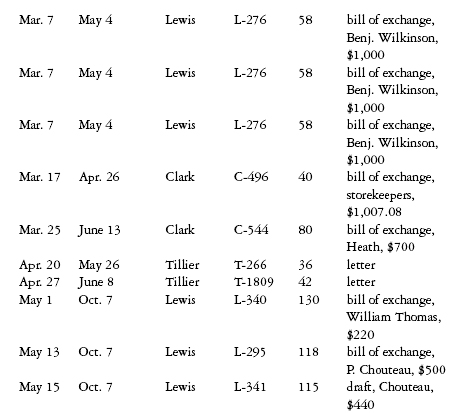

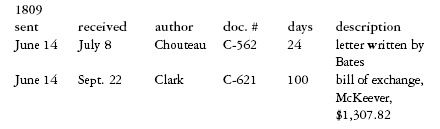

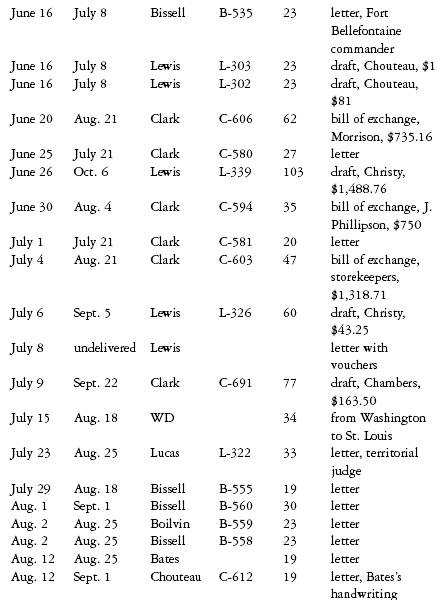

From January to August of 1809, letters written by Lewis and Clark containing drafts or bills of exchange averaged eighty-four days to arrive in Washington, whereas all other correspondence not relating to monetary issues averaged thirty-three days. The thirty-three-day transit time mirrored the average of thirty-seven days for all listed letters (except the two Chouteau letters) posted in 1803, 1804, and 1806. Taken together, the evidence suggests that someone was specifically delaying Lewis's and Clark's correspondence. In one instance, an important Lewis letter dated July 8, which included vouchers, was never delivered to Washington.14

Lewis departed Saint Louis on September 4, 1809, for New Orleans, on his way to Washington, and Clark followed three weeks later. Frederick Bates, the territorial secretary, then took command of the territorial government. After Lewis's death in 1809, William Clark had a mountain of duties to perform that prevented him from returning to the territory until July 7, 1810.15

It is difficult to identify the person or persons who might have contributed to the delay of Lewis's mail. Lewis certainly had enemies who understood how to financially strangle his progress, but they would have to have been living in or near Saint Louis and have had regular contact with him. One important piece to the puzzle is how the mail from Saint Louis reached Cahokia, which was the terminus for all incoming mail delivery. In March 1808, Territorial Secretary Frederick Bates wrote to a printer in Vincennes, Indiana, regarding forms for commissions and trading licenses, “if the Post Rider can be prevailed on to bring them to Cahokia.”16 Lewis wrote to Clark at the end of April 1808, “I have reason to believe that…letters and valuable papers which I dispatched by the succeeding mail, remained at Cahokia several days.”17

There are a few leading suspects who may have tampered with Lewis's mail, and Frederick Bates, Rufus Easton, Rodolphe Tillier, and John Hay top this list, but there is no definitive proof at this time linking any of these men to the deeds in question. Most historians would pick Frederick Bates, the territorial secretary, as the most likely suspect. Bates believed that he was a better administrator than Lewis and talked ill of him almost every time that he wrote to his brother. A particularly angry confrontation between the two men occurred at a Masonic celebration at the end of June 1809 when, according to Bates, Lewis challenged him to a duel. Bates declined, and from then on they had an agreement to steer clear of each other.18

Besides being the territorial secretary, Bates was also a member of the board of commissioners as the recorder of land titles. The board of commissioners was a federally appointed board assembled to hear and record land claims. Bates was absent from Saint Louis for long stretches of time because the commissioners frequently traveled to distant parts of the territory, and when they met in Saint Louis, most times it was at Fort Bellefontaine. After Lewis's arrival in March 1808, Bates took a 1,200-mile trip, “performing a circuit” as a member of the board of commissioners, departing Saint Louis on May 27, 1808, and returning on August 12.19 During this absence, two of Lewis's letters dated June 26 and July 6 were delayed for 102 and 60 days, respectively. For the remainder of 1809, Bates was busy recording land claims into ledgers and completing a report due by January 1810 to Albert Gallatin, secretary of the treasury. Bates also had to meet weekly with the commissioners at Fort Bellefontaine, where they held their meetings.20 The necessity of completing the report and traveling the eighteen miles to and from the fort was rigorous and would have demanded a large portion of his time, thus making it very difficult to believe that Bates was the culprit.

Rufus Easton, the Saint Louis postmaster, was also a territorial judge and lawyer. Easton had been a friend of Thomas Jefferson but lost his judgeship when he had a confrontation with James Donaldson, the attorney general of the Louisiana Territory. Donaldson accused Easton of taking advantage of a poor habitant on several occasions, and Easton, infuriated, beat Donaldson with a cane in a crowded courtroom. At the time of the delayed mail, Easton was one step away from having no job at all in the territory. He may have had opportunity, but a motive was lacking.

There were two persons who had better reasons to delay the mail. The first was Rodolphe Tillier, the factor at Fort Bellefontaine, and the other was the Cahokia postmaster, John Hay, a former British agent.

In 1808 the Fort Bellefontaine trading factory was moved 250 miles up the Missouri River and Tillier lost his job; however, Tillier believed Lewis had instigated his removal.21 Tillier needed a job, so he openly complained to his superior, John Mason, superintendent of Indian affairs, that Lewis had used public money to fund a private venture, namely the Missouri Fur Company. While Tillier's contempt and actions toward Lewis gave him a motive to steal the governor's mail, he would have been unable to carry out the deed, as he resided at Fort Bellefontaine, located eighteen miles from the Saint Louis post office.22

What Tillier lacked is a direct connection to the mail, to which John Hay, the Cahokia postmaster, had unfettered access. Hay began his career as a fur trader in 1791, having left Detroit a few years earlier. When he arrived in Cahokia he opened a merchant store with Andrew Todd, a well-financed partner who resided in Montreal, and called the business Todd & Hay.23 Todd became a secret partner to Spanish interests, putting up a sizeable chunk of money to fund the establishment of a fur company based in Saint Louis and appointing Hay as his agent.24 The Spanish lieutenant governor granted Todd “the exclusive privilege of trading with all the Indian nations” of the Upper Missouri region.25 But within the space of a few months, Todd contracted yellow fever and died in New Orleans, and Hay was left to pay Todd's creditors. To do that, he needed the books from the Spanish Fur Company in Saint Louis, so under the pretext of conducting a meeting, he stole the books and fled to Cahokia, making himself a fugitive, an example of his true character. Hay became the Cahokia postmaster in 1799. When Lewis arrived in Cahokia in November 1803, he selected John Hay as his interpreter when he met with the Spanish lieutenant governor in Saint Louis.26 Whatever bad business Hay previously had with the Spanish was behind them, and the conference between Lewis and the lieutenant governor went smoothly.

Prior to the departure of the Lewis and Clark Expedition in the spring of 1804, Hay helped Lewis by drafting a copy of the MacKay/Evans map, an essential piece of cartography depicting the Missouri River, which was based on the journeys of James MacKay and John Evans and drawn in 1797.27 This was the map that Lewis and Clark referred to for the first 1,500 miles of their journey. Hay also translated MacKay's journal of the Upper Missouri River, which was in French, and also assisted Lewis and Clark with the assembly of parcels of presents for various American Indian tribes.28

Historian Donald Jackson alluded to an aspect of Hay's character, which remained hidden from Lewis in 1803–1804 but gives some indication that his true intentions were not always honorable. When Lewis and Clark returned to Saint Louis from their explorations in late September 1806, Lewis wrote to President Jefferson to describe the trip; surprisingly, a copy of this letter arrived in Canada before it was delivered in Washington.29 Jackson believed that Hay intercepted the letter at Cahokia and forwarded a copy to the British in Montreal. The letter was a summary of the cardinal discoveries made by Lewis and Clark on the expedition to the Pacific Ocean. It was of major value and consequence to the British. John Hay may have been involved in sending the letter to Canada, but because there is no evidence, this is mere speculation.

It is not clear from the research who might have tampered with Lewis's mail and it is also not the intent of the author to condemn any historical figure without definitive proof. While much historic documentation exists in the Saint Louis record today, information that would lead to specific persons who disagreed with policies implemented by Lewis and Clark enough to tamper with their mail has not come to light.