The cause of dentoalveolar injuries varies in children and adolescents. It also varies among age, sex, and demographics.

The true incidence of dental and oral trauma is unknown as many injuries are treated in a dental office or not at all.

Management of dental trauma varies greatly between primary teeth and permanent teeth.

Early, evidence-based treatment is vital for improving long-term prognosis of the injured tooth/teeth and/or surrounding oral structures.

6.1 History

Dentoalveolar trauma has always been part of human life. Accidents or altercations with other humans or animals are examples of causes of early dental trauma. The treatments provided by early dental surgeons paved the way for some of the basic principles that we use today for the treatment of dental trauma.

A Sumerian text of 5000 BC was the first text to describe dental decay and is the first written record of dentistry. But it was not until 500–300 BC that treatment for dental trauma was recorded. Hippocrates and Aristotle write about using wires to stabilize loose teeth and fractured jaws. Hippocrates emphasized the importance of obtaining the proper occlusion in order to improve healing, which is a basic concept that is still used today. It was not until around 59 BC–AD 17 that treatment of the pulp of a broken was addressed. Archigenes described that a broken tooth should undergo intrapulpal cautery with a hot iron instrument. Claudius Galen (~AD 130–200) also believed that proper occlusion must be reestablished in order to obtain the best healing when repairing dentoalveolar fractures [1, 2].

It was not until 1895 that C. Edmund Kells took the first dental X-ray on a living person in the United States [1]. Radiology is a vital part of the workup and diagnosis of dental trauma and is still used today.

6.2 Etiology and Incidence

The cause of dentoalveolar injuries varies in children and adolescents. It also varies among age, sex, and demographics. Because dentoalveolar injuries are often treated in a private clinic, they are never recorded into large hospital databases. This makes it difficult to determine the true incidence and prevalence of dentoalveolar trauma. To further this problem, many minor dental injuries go unreported entirely. Understanding dentoalveolar injuries is important because they can result in complications associated with dental eruption, occlusion, facial growth, and alveolar development.

In children, falls are the common cause for injuries to primary teeth and young permanent teeth [3]. Up to 40% of preschool children sustain dentoalveolar injuries with the peak between ages 2 and 3 [4]. This usually occurs when children are gaining better mobility and more prone to falls. Dentoalveolar injuries (60%) are the most common facial injury in children under age 5 [5]. There is a bimodal trend with another peak incidence from ages 8 to 12 [6]. This is more commonly due to accidents during play such as bicycle accidents and falls from playground equipment. Accidents are more common in men than women. Adolescents commonly experience injuries from motor vehicle accidents and sports-related injuries. Unfortunately, child abuse is another cause of dental trauma as many cases of child abuse involve some oral and facial injury.

Maxillary central incisors are the most frequently traumatized teeth particularly if they are protrusive or associated with a class II malocclusion. Overjet greater than 4 mm increases the likelihood of trauma to the maxillary central incisors by 2–3 times [7]. Maxillary lateral incisors followed by mandibular incisors are the next most commonly involved teeth.

6.3 History and Physical Exam

Summary of tetanus prophylaxis with TIG in routine wound management

History of adsorbed tetanus toxoid-containing vaccines (doses) | Clean, minor wound | All other woundsa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

DTaP, Tdap, or Tdb | TIGc | DTaP, Tdap, or Tdb | TIGc | |

Unknown or <3 doses | Yes | No | Yes | Yesd |

Unknown or ≥3 doses | Noe | No | Nof | No |

Clinical examination should include a full head and neck exam. Examination should include the following: extraoral soft tissues, intraoral soft tissues, maxilla, mandible, TMJ, alveolar bone, and teeth (mobility, missing, percussion, and pulp testing).

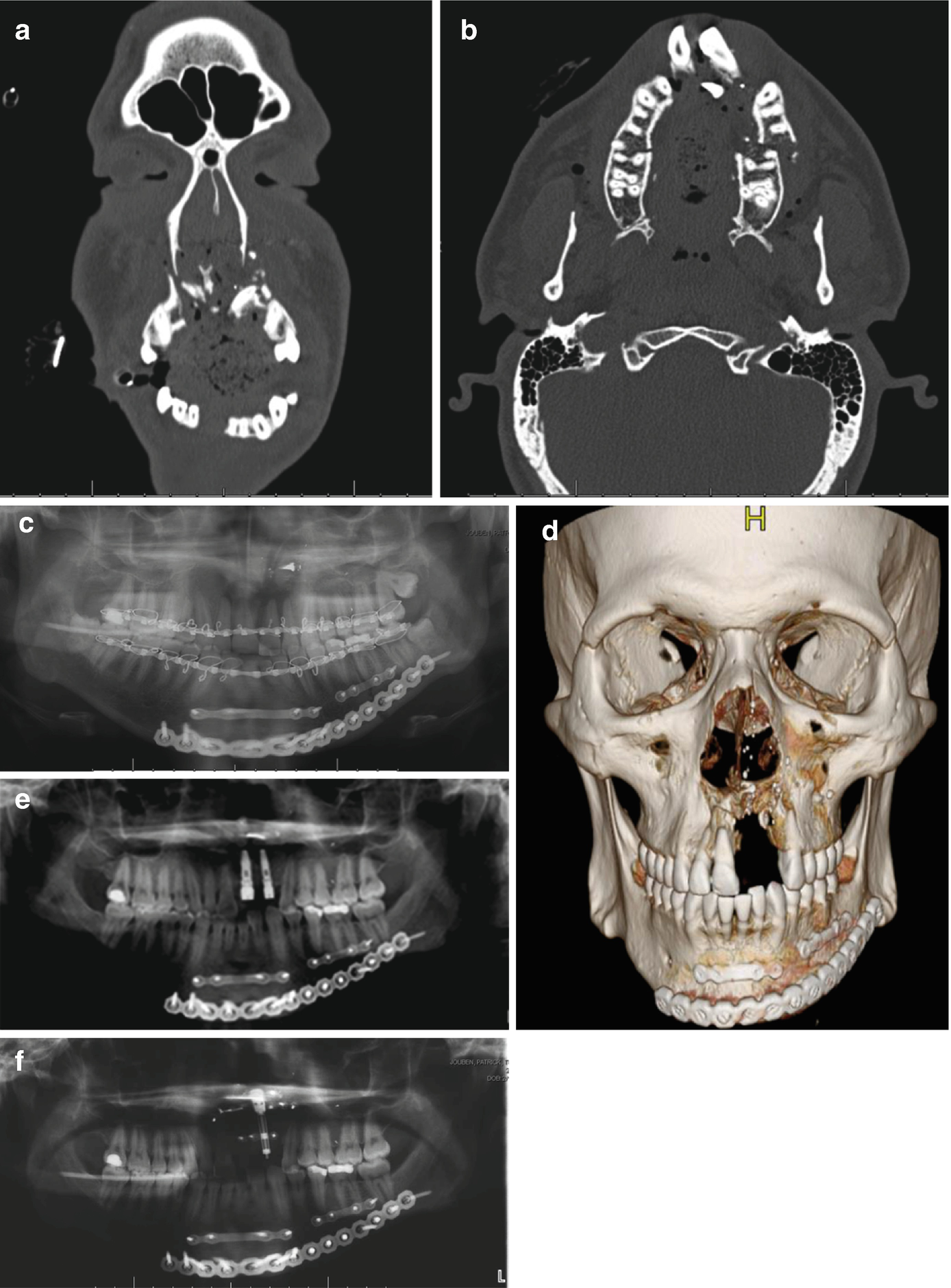

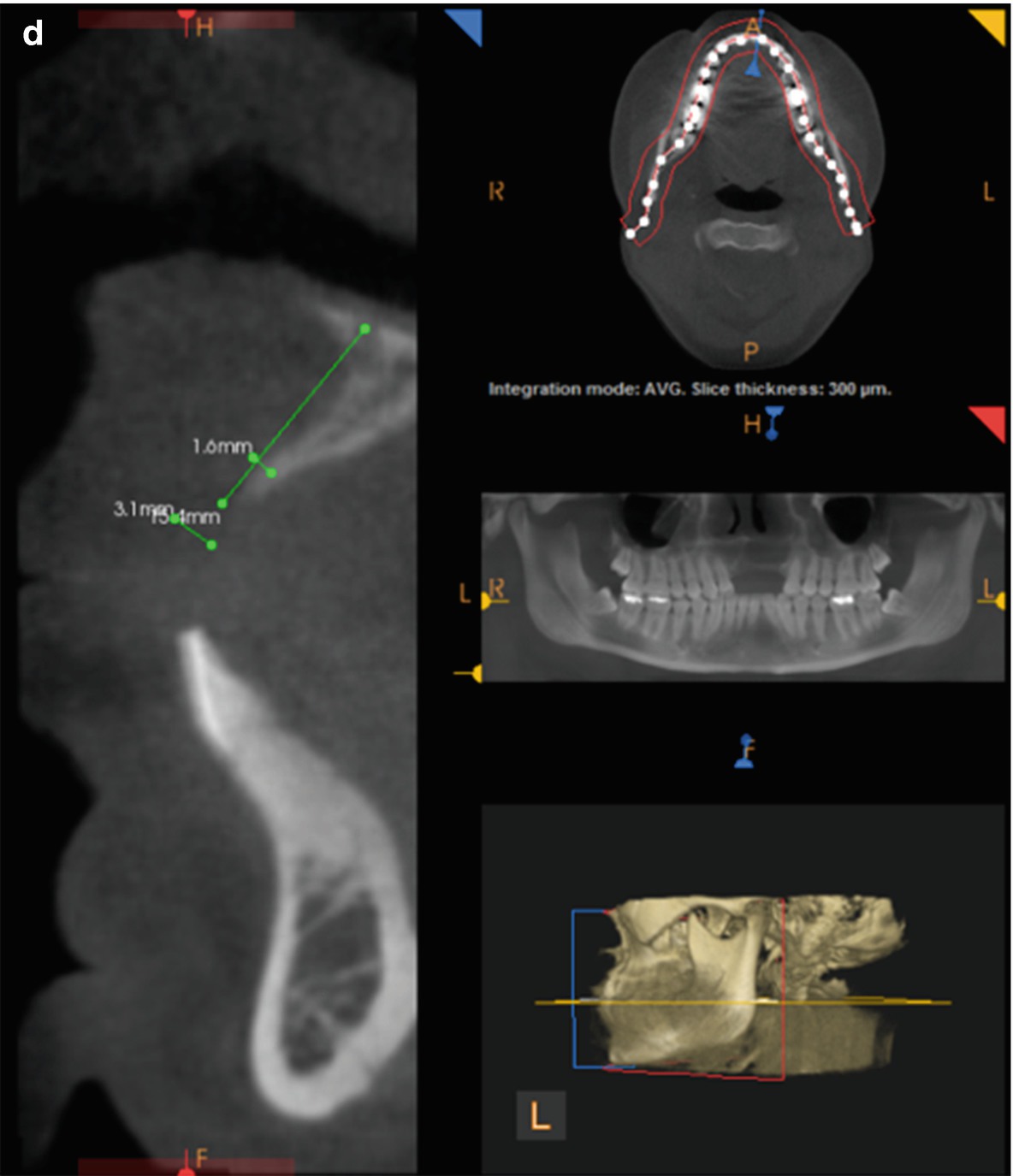

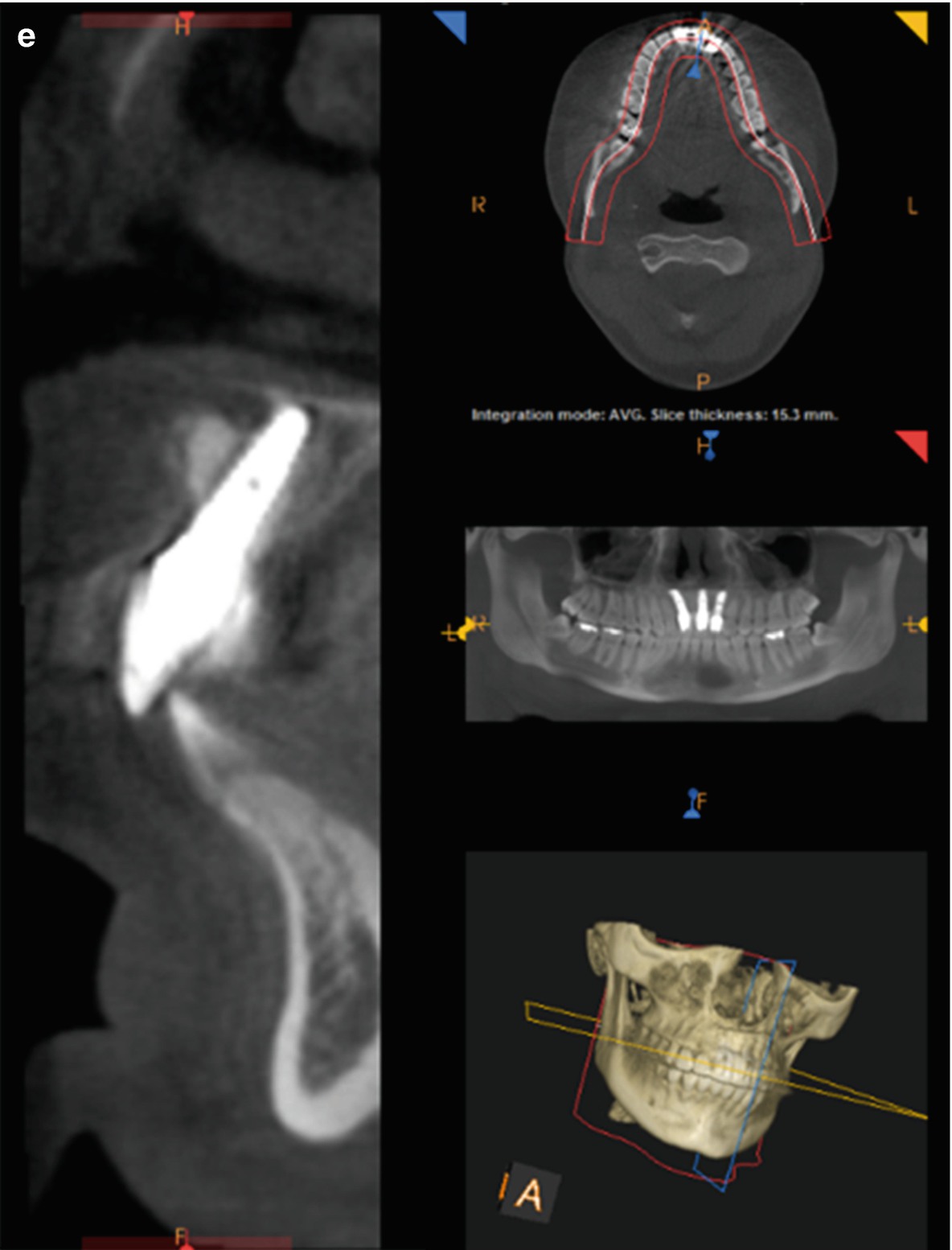

Adult complex facial trauma including maxilla and mandibular alveolar complex. (a) Coronal CT scan. (b) Axial CT scan. (c) Panoramic radiograph. (d) 3D recon. (e) Panoramic radiograph with dental implants. (f) Panoramic radiograph with distractor. (g–k) Clinical photographs

6.4 Classification of Traumatic Injuries to Teeth and Supporting Structures

Injuries to the dental hard tissue and pulp

Injuries to the dental hard tissue, pulp, and alveolar process

Injuries to the periodontium

Injuries to the gingiva and/or oral mucosa

- Injuries to the dental hard tissue and pulp:

Crown infraction (i.e., craze line or crack, no loss of tooth substance)

- Crown fracture:

- Uncomplicated crown fracture:

Enamel fracture

Enamel dentin fracture without pulp exposure

- Complicated crown fracture:

Enamel dentin fracture with pulp exposure

- Injuries to the dental hard tissue, pulp, and supporting bone:

- Uncomplicated crown-root fracture

Fracture involving enamel, dentin, and cementum without pulp involvement

- Complicated crown-root fracture:

Fracture involving enamel, dentin, and cementum with pulp involvement

- Root fracture

Fracture involving dentin and cementum with pulp exposure

Alveolar fracture

Maxillary or mandibular fracture

- Injuries to the periodontium:

Concussion—injury to the periodontium that causes sensitivity to percussion but does not loosen or displace the tooth

Subluxation—tooth is loosened but not displaced

- Luxation—tooth is loosened and displaced:

Intrusion—displacement into the socket

Extrusion—partial displacement from the socket

Lateral luxation—displacement into mesial or distal direction

Avulsion—tooth is displaced completely from the socket

- Injuries to the gingiva and/or oral mucosa:

Laceration to the gingiva or oral mucosa

Contusion

Abrasion

6.5 Treatment of Dentoalveolar Injuries

6.5.1 Primary Dentition Injuries

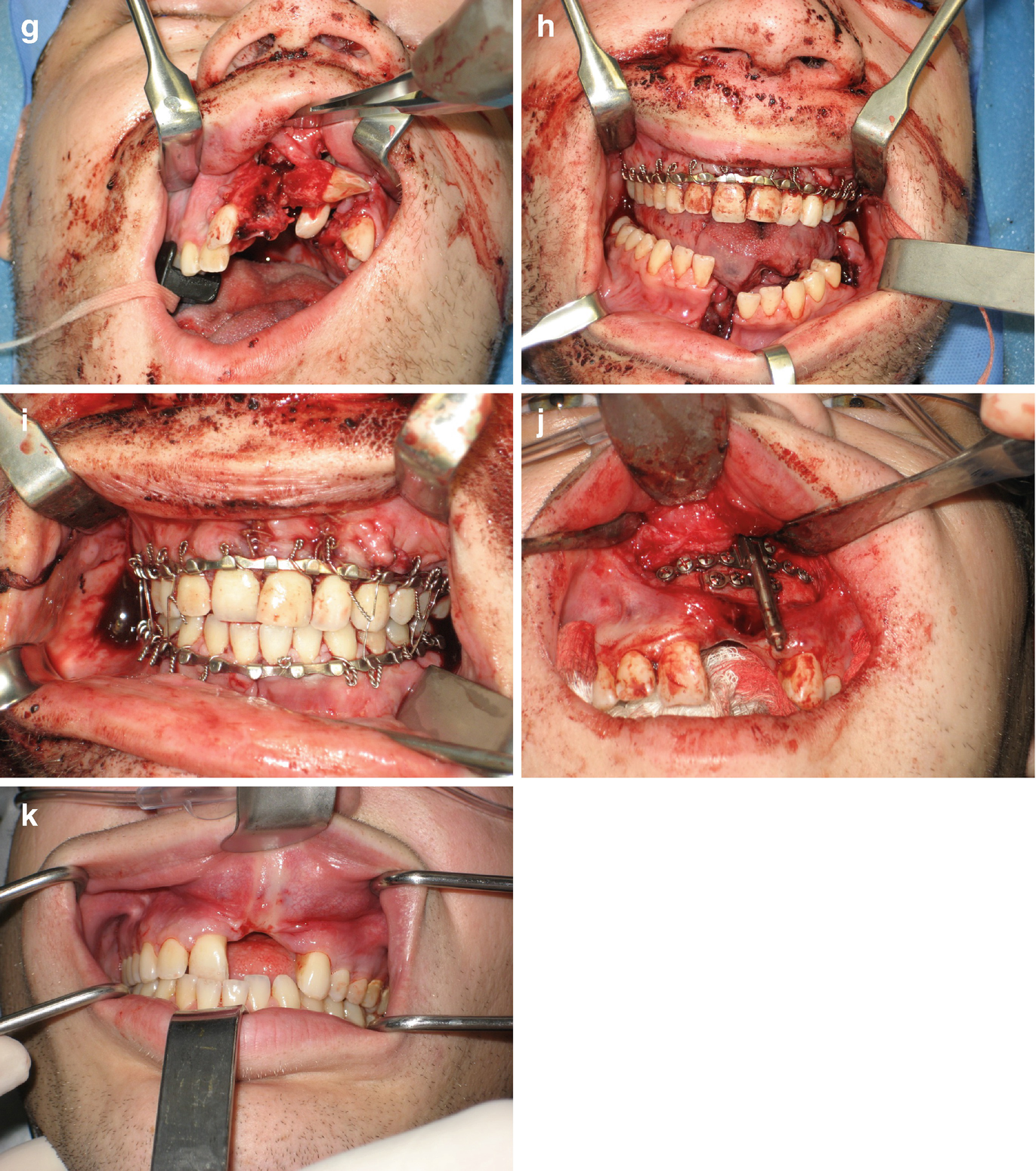

Pediatric mandible fracture with intruded dentition. (a, b) Axial CT scans. (c–e) Clinical photographs

6.5.1.1 Injuries to the Dental Hard Tissue and Pulp

Crown Infraction

Radiographs are taken to assess for other injuries and to look for physiologic root resorption. Pulp testing should be performed at the time of injury and repeated at 6–8 weeks after injury. Clinical follow-up should be done at 1 week and 6–8 weeks after injury.

Crown Fractures

Uncomplicated Crown Fractures

Radiographs are taken to assess for other injuries and to look for physiologic root resorption. Sharp edges are smoothed or treated with composite resin. Pulp testing should be performed at the time of injury and repeated at 6–8 weeks after injury. Clinical and radiographic follow-up should be done at 6–8 weeks and 1 year.

Complicated Crown Fractures

These fractures involve enamel, dentin, and pulp. Because there is pulp involvement, treatment will depend on the life expectancy of the tooth and the child’s behavior. If the root is immature, then a pulpotomy is indicated to preserve pulp vitality in the root. If the root is mature, then a pulpectomy with a resorbable paste should be ideally performed within 1–2 days after injury. Sedation or general anesthesia may be required depending on the child’s behavior. Clinical follow-up should be at 6–8 weeks and 1 year.

Crown-Root Fractures

If the fracture extends from the crown to the root in a primary tooth, then it should be extracted. Radiographs should be taken to assess where the fracture is located, and if there is damage or displacement in the permanent tooth bud and damage to the surrounding alveolus. The root fragments should be left to resorb if they cannot be easily extracted. This is performed to protect the permanent tooth bud. A soft diet for 2 weeks should be recommended. Follow up clinically and radiographically at 1 year and every year until eruption of the permanent successor.

Root Fractures

Radiographs should be taken to look for other injuries, physiologic root resorptions, and displacement of permanent tooth bud. If the fracture is in the apical third and the coronal fragment is stable, then the tooth can be followed with serial pulp tests and radiographs. If the coronal segment is mobile or displaced, then it should be extracted. If the root fragment cannot be easily extracted, then it should be left to resorb. A soft diet for 2 weeks should be recommended. Follow-up should be at 1 week. Clinical and radiographic follow-up should be at 6–8 weeks and 1 year. Then there should be yearly follow-up until the eruption of the permanent successor.

6.5.1.2 Injuries to the Periodontium

Concussion

Only clinical sign is pain to percussion. Radiographs should be taken to look for other injuries and physiologic root resorption. Treatment is often not needed. Soft, no-chew diet for 2 weeks is recommended. Close follow-up is recommended to evaluate for infection and/or pulpal necrosis. Follow-up should be at 1 week and 6–8 weeks after injury.

Subluxation

The tooth is mobile but not displaced. Clinically, there will be bleeding at the gingival margin and it will be sensitive to percussion. Radiographs should be taken to look for other injuries such as evidence of injury. Soft, no-chew diet for 1–2 weeks is recommended. Pulp testing should be performed at the time of injury and repeated at 6–8 weeks after injury.

Lateral Luxation

The tooth is displaced and may be mobile. Radiographs are taken to look for the placement of the root within the alveolus. If the tooth is out of occlusion then it can be allowed to passively reposition. If the tooth is in occlusion, then it can be gently repositioned if this will not interfere with the developing tooth bud. Extraction is recommended if the tooth is severely displaced particularly in the labial direction where it can interfere the developing tooth bud. Also, extraction is recommended if it is severely displaced and interfering with occlusion. The patient should be on a soft diet for 2 weeks. Follow-up should be at 1 week and 2–3 weeks. Clinical and radiographic follow-up should be at 6–8 weeks and 1 year.

Intrusion

The tooth is displaced into the alveolus. This carries the highest risk of injury to the permanent tooth bud. Radiographs are taken to evaluate if there is contact between the permanent tooth bud and the intruded primary tooth. If there is no contact, then monitor closely for infection and pulpal necrosis, and allow for re-eruption. Within 4–5 months, most intruded primary incisors will re-erupt [8]. If the intruded tooth impinges or contacts the permanent tooth, then it should be gently and carefully extracted. Buccal and lingual forces should not be placed on the tooth during extraction as this can further injure the permanent successor. If the tooth becomes infected, then it should be extracted. Follow-up should be at 1 week. Clinical and radiographic follow-up should be at 3–4 weeks, 6–8 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year. Then there should be yearly follow-up until the eruption of the permanent successor.

Extrusion

The tooth is displaced away from the socket and is mobile. Radiographs are taken to look for other injuries and physiologic root resorption. If the tooth is minimally displaced and an immature developing tooth, then it can be gently repositioned or left for spontaneous repositioning. If the displacement is severe and the root is fully formed, then the tooth should be extracted. Follow-up should be at 1 week. Clinical and radiographic follow-up should be at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 1 year.

Avulsion

Socket is clinically found empty and filled with coagulum. Avulsed primary teeth should not be replanted as this can cause injury to the developing tooth bud as well as lead to an ankylosed primary tooth [9]. Radiographs are taken to verify that the tooth is not intruded or if there is a coronal fracture with a retained root. All missing teeth should be accounted for as there is a risk of aspiration. Soft diet is recommended for 1 week as well as good oral hygiene. Follow-up should be at 1 week. Clinical and radiographic follow-up should be at 6 months and 1 year. Then there should be yearly follow-up until the eruption of the permanent successor.

6.5.2 Permanent Dentition Injuries

6.5.2.1 Injuries to the Dental Hard Tissue and the Pulp

Crown Infarction

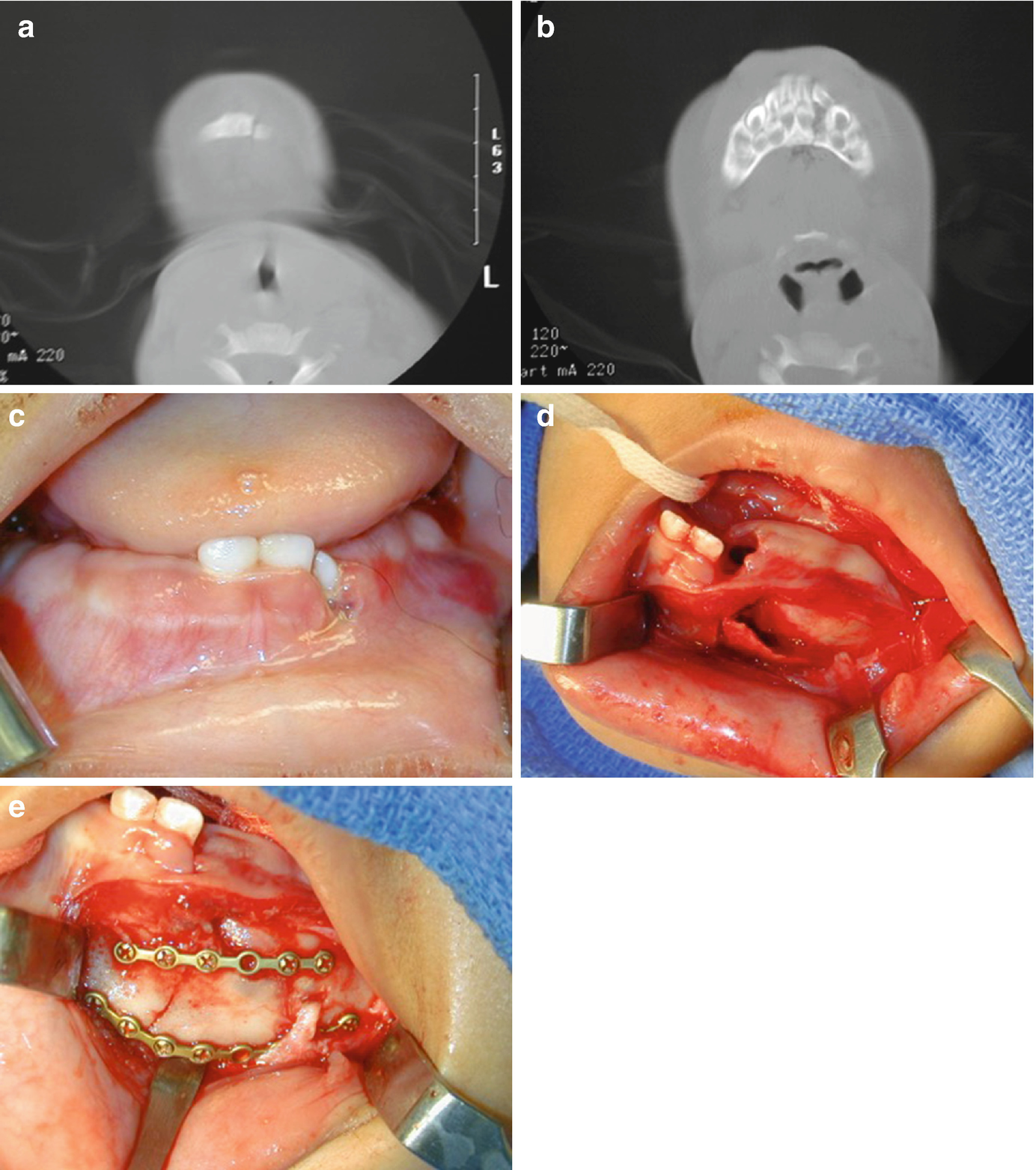

Dentition loss from trauma and reconstruction with dental implants. (a–e) CT scans. (g, h) Panoramic radiographs. (i–n) Clinical photographs

Crown Fractures

In the child to optimize comfort and functional outcomes, the child is treated as soon as possible, but most fractures of permanent teeth including those with pulp exposures can be treated hours after the injury.

Uncomplicated Crown Fractures

Treatment is determined by the depth of the crown that is involved. If the fracture is in the enamel only, then smoothing the edges may be the only treatment needed, but if there is a defect in the tooth then bonding composite resin may be warranted. Pulp is not exposed in uncomplicated crown fractures. Pulpal complications are rare (0–6%) [12] unless luxation occurs at the same time (25%) [13]. The blood supply to the pulp of the tooth remains intact if it is not luxated, which improves the prognosis. If dentin is exposed then restoration with dental restorative materials such as composite resin is needed. Fragments can be bonded back into position with good long-term results [14]. Deep fractures that remain untreated for more than 24 h have a high incidence of pulp necrosis; therefore, cover dentine as soon as possible [11]. Clinical and radiographic follow-up should be at 6–8 weeks and 1 year.

Complicated Crown Fractures

The pulp is exposed in complicated crown fractures. Prognosis is dependent on the following factors: length of time since the injury occurred, maturity of the root, size of pulp exposure, and condition of the pulp (vital or nonvital). If the root is immature, the goal is to maintain a vital pulp to allow for root maturation/development and closure of the apex. Direct pulp caps and pulpectomies are not good choices because they do not allow for maturation of the root and closure of the apex. A partial pulpotomy is performed in immature teeth. If the pulp is exposed a few hours, then inflammation rarely extends beyond 2 mm and conservative treatment with a partial pulpotomy is the best choice for treatment [15]. 2–3 mm of the pulp is removed and capped with calcium hydroxide or mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) [16, 17]. Glass ionomer is then placed and covered with composite resin. Necrotic, immature teeth must undergo pulpectomy with regenerative endodontic procedures or apexification [18].

In mature teeth, a direct pulp cap can be performed if the exposure is pinpoint and treatment is taking place soon after injury. The preferred treatment in mature teeth with closed apices if the pulp exposure is large is pulpectomy. Clinical and radiographic follow-up is at 6–8 weeks and 1 year.

Crown-Root Fractures

Extraction is recommended if the fracture involves more than one-third of the root or if the fracture is longitudinal. Replacement of the missing tooth can include orthodontic closure of the missing space, autotransplantation, prosthodontics, or implant placement. If enough root structure remains, then crown lengthening, orthodontic extrusion, or surgical repositioning may be required. Otherwise, conservative therapy can be used to restore the tooth.

In immature teeth, the goal is to preserve the developing root to allow for root maturation and apex closure. Pulp treatment and restoring loss tooth structure is the next step. Definitive treatment can be performed after the patient is older. If the tooth is nonrestorable, then decoronation should be performed to preserve the alveolar bone [19]. This may prevent the need for a ridge augmentation. The root can be extracted at the time of implant placement once growth is complete.

Root Fractures

Root fractures are fractures involving only the roots. Most fractures occur in the apical and middle one-third. Radiographs are taken but often the fracture will not show on a radiograph until 1–2 weeks after injury. Also, root fractures are frequently diagonal as well as horizontal and may not show a periapical radiograph. Root fractures in the apical and middle one-third usually do not require splinting unless there is excessive mobility. If the tooth is extremely mobile then splinting for 12 weeks with a rigid splint is needed. It is rare for the fracture to occur in the cervical one-third but if it does then the tooth may require extraction or orthodontic extrusion. Endodontic therapy may be required for teeth that develop pulpal necrosis. In immature teeth, root fractures are often irregular and are horizontal and vertical. They will heal without treatment due to the large pulp that is developmentally active.

Alveolar Fractures

Splinting schedule

Subluxation—flexible splint—up to 2 weeks for patient comfort only |

Extrusive luxation—flexible splint for 2 weeks |

Lateral luxation—flexible splint for 4 weeks |

Intrusive luxation—incomplete root formation: eruption without intervention, if no movement within few weeks, orthodontics (if intruded >7 mm reposition surgically or with orthodontics); complete root formation: if <3 mm of intrusion—eruption without intervention, if no movement within 2–4 weeks, reposition surgically or with orthodontics (before ankylosis develops), stabilize with orthodontics or surgically repositioned tooth with flexible splint × 4–8 weeks |

Alveolar segment—rigid stabilization × 8–12 weeks |

Avulsed teeth—flexible splint 7–10 days |

Root fracture—flexible splint × 4 weeks (if fracture near cervix, stabilize × 4 months) |

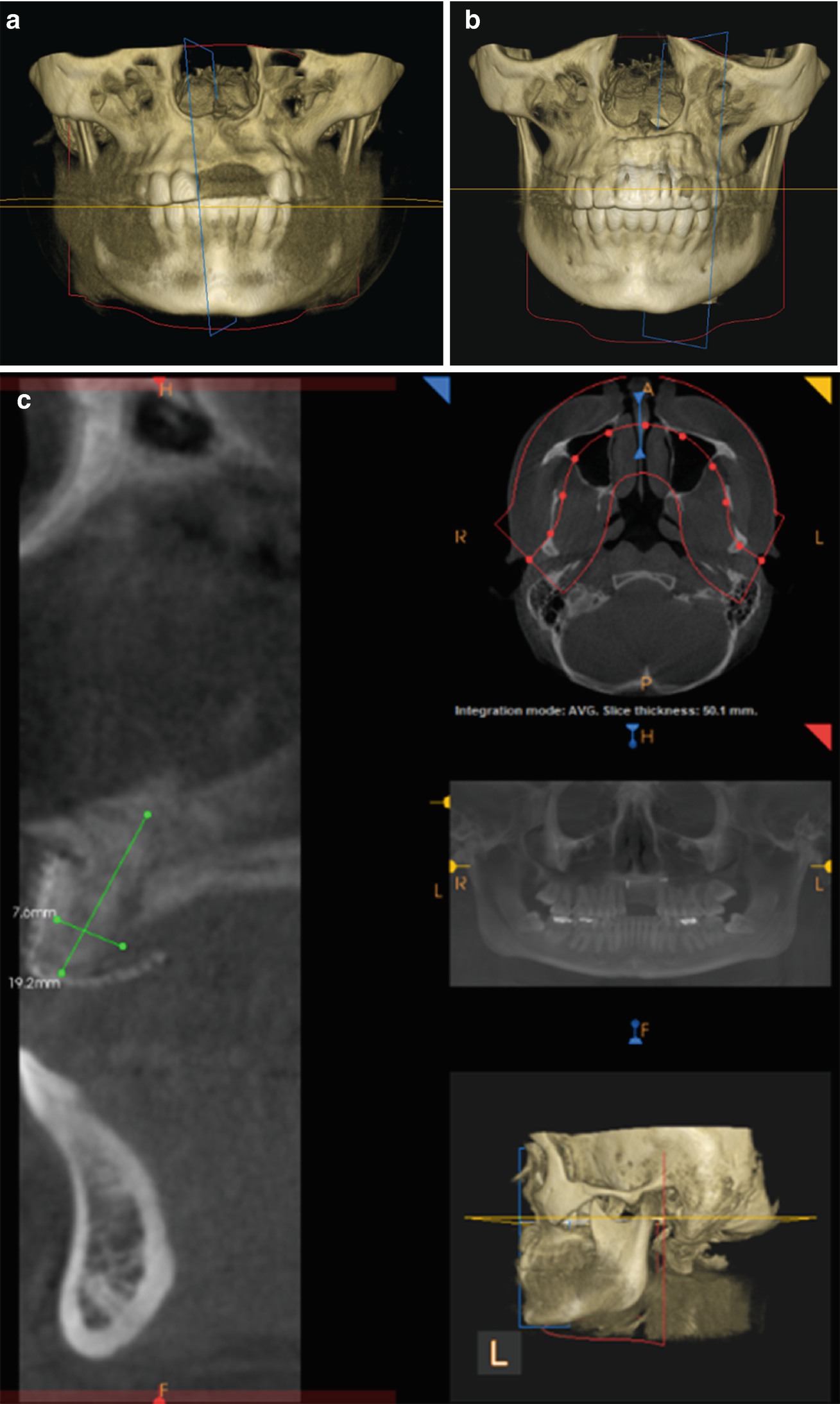

Mandibular lateral incisor loss from dentoalveolar trauma reconstructed with block grafts from the calvarium. (a) Clinical photograph. (b) Bone graft blocks. (c) Grafts secured intraorally. (d) Intraoral healing. (e) Abutment placed. (f) Panoramic radiograph. (g) Final restoration

6.5.2.2 Injuries to the Periodontium

Concussion

No treatment is required initially. If there is pain with biting then the tooth can be taken out of occlusion. Teeth should be followed for infection, pulpal necrosis, and pulp canal obliteration. Root resorption is rare. Soft diet is recommended for 1 week. Clinical and radiographic follow-up should be at 4 weeks, 6–8 weeks, and 1 year.

Subluxation

Treatment involves taking the tooth out of occlusion. A flexible splint can be placed for patient comfort for 2 weeks. Soft diet is recommended for 1 week. Teeth should be followed for infection, pulpal necrosis, and pulp canal obliteration. Root resorption can occur. Clinical follow-up for pulp testing and splint removal should be at 2 weeks (Table 6.2). Clinical and radiographic follow-up should be at 2 weeks, 4 weeks, 6–8 weeks, and 1 year.

Extrusion and Lateral Luxation

Teeth should be disimpacted, repositioned, and splinted into place as soon as possible. The tooth should not interfere with occlusion. Teeth should be splinted to 4 weeks to allow for healing of alveolar fractures (Table 6.2). Delayed repositioning leaves the root in contact with the bone which increases the chances of root resorption. Common sequelae include pulp necrosis (40% in children [20] and 58% in adults [21]), pulp canal calcification (40%) [20], and root resorption. In a mature tooth, pulpectomy is performed at 1 month if there is no evidence of root resorption (26%) [21]. In immature teeth, pulp therapy is only initiated if there is evidence of pulp necrosis. When the apices are open, there is a chance for revascularization. Soft diet is recommended for 1 week. Clinical and radiographic follow-up should be done after 2 weeks. Clinical and radiographic follow-up and splint removal should be done after 4 weeks. Clinical and radiographic follow-up should be at 6–8 weeks, 6 months, 1 year, and yearly for 5 years.

Intrusion

Treatment is determined by apical development. Intrusion injuries often have a poor prognosis. Most intruded teeth will become necrotic [22]. Resorption occurs in about 50% [11]. In mature teeth that are intruded less than 3 mm, no intervention is needed. If they do not move within 2 weeks, then they should be surgically or orthodontically extruded before they ankylose. In mature teeth that are intruded more than 3 mm, the preferred treatment is surgical repositioning with splinting for 4–8 weeks (Table 6.2). Early pulpectomy should be performed to prevent the start of inflammatory root resorption [10]. In immature teeth that are intruded less than 7 mm, treatment should be delayed. Due to the open apex and softer, more malleable bone, the teeth will often spontaneously re-erupt. If they do not move within 3 weeks, then they should be orthodontically extruded to prevent ankyloses. If they are intruded more than 7 mm, then they should be orthodontically or surgically repositioned. Clinical and radiographic follow-up should be at 2 weeks, 1 month, 2 months, 6 months, and yearly. The splint should be removed at the 1–2-month follow-up. If root resorption is detected in the immature tooth, then pulpectomy with calcium hydroxide should be performed. Root resorption can occur quickly in immature teeth.

Avulsion

Prognosis for an avulsed permanent tooth is dependent on the amount of time spent out of the socket. The sooner the tooth is replanted the better the prognosis. After replantation, a flexible splint is applied for 7–10 days followed by endodontic therapy (Table 6.2). Periodontal ligament cells must remain vital to have good prognosis. The most commonly avulsed tooth is the maxillary central incisor and most often affects children 7–10 years of age [23]. For the best prognosis, the tooth should be replanted immediately or placed in a suitable storage medium such as milk, Hanks’ balanced salt solution, or saliva. Contact lens solution has even been found to be a suitable storage medium [24]. Teeth should never be stored or rinsed with tap water.

Replantation involves holding the tooth by the crown to avoid damaging the PDL. The tooth is gently washed with saline. The tooth is replanted into the socket as soon as possible. A light splint made with monofilament nonresorbable suture or orthodontic wire and composite resin is used to splint the tooth for 7–10 days. A complete pulpectomy is performed at 1 week in mature teeth. Endodontic therapy can be delayed in immature teeth as they may revascularize. Resorption can occur quickly; therefore, follow-ups with short intervals are required in immature teeth. If orthodontic therapy is planned for a young person with open apices and a long dry time, then the tooth may not need to be replanted. These teeth are at risk for ankylosis with root submergence and root resorption. This will give a poor orthodontic result, whereas orthodontic closure could be a suitable alternative for the missing tooth. Others argue that immature teeth with long dry times should always be replanted due to chances of healing, preservation of alveolar bone, psychological considerations, and limited alternatives for replacements in a young child.

Follow-up after avulsion should be at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. After that it should be yearly for 10 years. If the tooth submerges more than 3 mm in young children then it should be extracted or decoronated because it is likely ankylosed [11].

6.5.3 Treatment of Trauma to the Gingiva and Alveolar Mucosa

6.5.3.1 Abrasion

An abrasion is wound that is superficial where the gingiva is rubbed or scratched. The wound should be gently cleaned with saline and inspected for debris. Debris should be removed to prevent tattooing. Prophylactic antibiotics are generally not needed.

6.5.3.2 Contusion

A contusion is a bruise or a hemorrhage of subcutaneous tissue without laceration of the overlying epithelial tissue. Observation is usually adequate care for these injuries. If a hematoma forms, then it should be drained. Prophylactic antibiotics are generally not needed.

6.5.3.3 Laceration

The most common facial injury is a laceration. Gingival lacerations should be cleaned and reapproximated. Bone should be covered. Sliding and advancement flaps may be needed. Care should be taken to place keratinized tissue in the alveolar region. Antibiotics such as amoxicillin are recommended. If the patient is allergic to penicillin, then clindamycin is given.

6.6 Conclusion

Dental trauma is a common occurrence particularly in the pediatric and adolescent age groups. Prevention is always best. This is done by improving public knowledge on the use of face shields and mouth guards during sports, wearing helmets with face shields on ATVs, and wearing seat belts to decrease injuries from MVCs. Unfortunately, despite our best efforts, trauma does happen. Early treatment of dentoalveolar injury leads to improved outcomes. This can be achieved through education of the general public such as parents, caregivers, coaches, teaches, etc. so they can feel comfortable and know how to quickly manage the trauma in the initial stages. It is also important for the patient to be evaluated and treated quickly by a person trained in the management of dental trauma such as an oral and maxillofacial surgeon, an endodontist, or a general dentist. Dentists and dental specialists will continue to improve outcomes by following the most up-to-date, evidence-based research regarding dental trauma.