On Friday, July 24, 1992, a Mrs. Lillian Rose Vorhaus Oppenheimer, ninety-three years old and a native New Yorker, died of complications after a heart operation at the Beth Israel Medical Center in Manhattan. Mrs. Oppenheimer was survived by her four children by her first husband, Mr. Joseph B. Kruskal, by her four stepchildren by her second husband, Mr. Harry C. Oppenheimer, by her twenty-six grandchildren, thirty great-grandchildren, and by anyone who has ever had a serious interest in origami.

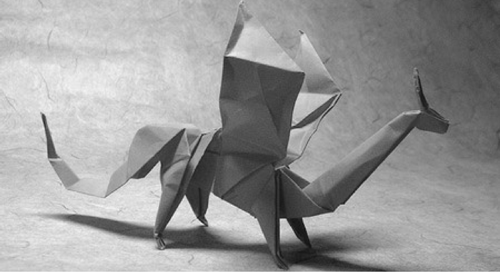

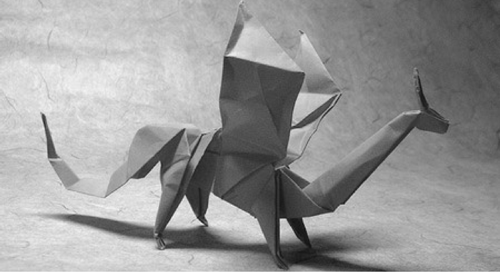

There is a common belief that origami is an ancient art with mystical origins in Japan that was brought to the West long ago by nameless pioneer paper folders. In fact, origami as we know it today has its origins in Lillian Oppenheimer’s apartment on top of the Hotel Irving, in Gramercy Park, Manhattan, where she established the Origami Center of America in 1958. Indeed, the entire history of origami in the twentieth century might be told as Oppenheimer’s story, the uplifting tale of a New York socialite who overcame tragedy and found purpose in life through paper folding. Or it might equally be told as the cautionary tale of a maverick Jewish sexologist whose pioneering work on a bibliography of an obscure subject brought origami to worldwide attention, but whose controversial opinions and behaviors consigned him to the margins of the very enterprise he had helped to establish. Or indeed as the story of a South African stage illusionist who achieved everlasting fame through folding tiny figures on TV. Or perhaps as a heroic folktale, of how a humble, self-taught Japanese paper-folding genius was saved from a life of obscurity as a door-to-door salesman by a series of chance encounters. These are all versions of the incredible recent history of paper folding—a history with as many folds and creases as an origami rhombicuboctahedron, or one of origami master Satoshi Kamiya’s famous one-sheet, folds-only, super-lifelike scaly dragons. Paper doesn’t merely record drama: it enacts drama. It doesn’t merely tell a story: it is a story.

Lillian Oppenheimer first took up paper folding in 1928, when her young daughter was in the hospital recovering from a serious operation and Lillian found that she had 1) time on her hands; and 2) a copy of a popular new book by William D. Murray and Francis J. Rigney, titled Fun with Paperfolding—the first book in English devoted solely to the art and craft of paper folding. Lillian sat in the hospital waiting room making models, her daughter recovered, they returned home, and Lillian got on with the serious business of raising her family. Twenty years later, when her husband became ill, she once again found herself stuck in hospital waiting rooms, and once again found herself playing with paper. After the death of her husband, she took handicraft classes at the New School for Social Research in New York with a young woman who had trained as a kindergarten teacher in Germany, and who taught the class some basic paper-folding techniques. Enthused, Lillian started reading books about the craft, and began meeting friends and others to share models and ideas: she preferred the exotic term “origami” to plain old “paper folding.” (In its original context, origami—from “oru,” to fold, and “kami,” paper—refers specifically to folded certificates rather than to recreational paper folding, but it had gradually been adopted as a common term for paper craft in Japan.) When an article about Lillian and her origami evenings appeared in the New York Times in June 1958, people started asking for lessons and demonstrations, and so the Origami Center of America was born, meeting on Monday evenings and Tuesday afternoons in Lillian’s apartment in the Hotel Irving. In the words of her friend and fellow paper folder Florence Temko, “In these meetings, Lillian established the spirit that pervades the origami world to this day. We all folded together and whoever had come across something new or created a model, shared it with the others.” Late in life, Lillian had found her role. She helped organize the first origami exhibition in America, at the Cooper Union Museum in New York in 1959, she began producing a newsletter, The Origamian, and she visited and corresponded with origamists and enthusiasts around the world. She was also, incidentally, a puppeteer, one of the founding members of the Puppetry Guild of Greater New York, and an amateur ventriloquist, writing books with her friend Shari “Lamb Chop” Lewis. She was, in other words, a phenomenon. International Origami Day is rightly celebrated on October 24, Lillian’s birthday: she is, without doubt, the founder of origami as a popular modern recreation.

As for the maverick Jewish sexologist . . . Gershon Legman was the amazingly freethinking son of immigrants, born in Scranton, Pennsylvania, in 1917. He was a man of broad tastes and enormous energies: often credited as one of the inventors of the modern vibrating dildo, an achievement more than sufficient to secure both his notoriety and his fame, he also worked for the sex researcher Alfred Kinsey, and at the age of just twenty-three he published a book memorably titled Oragenitalism: An Encyclopaedic Outline of Oral Techniques in Genital Excitation. Part 1: Cunnilinctus (1940), with ambitious plans for a follow-up book on fellatio. (His poor parents had hoped he’d become a rabbi.) Oragenitalism was effectively banned when its publisher’s premises were raided by police. Undeterred, Legman went on to publish numerous other studies of sexual behavior and folklore, including The Horn Book: Studies in Erotic Folklore and Bibliography (1964) and The Rationale of the Dirty Joke: An Analysis of Sexual Humor (1968). Apparently, allegedly—the legends of Legman are legion—he took up paper folding merely as a hobby after an accident, but he pursued it with the same enthusiasm and determination as his wide-ranging studies in sex. He researched both the history and the contemporary worldwide practice of paper folding, and compiled and published a bibliography of his findings in 1952. He named the standard four-cornered origami fold the “blintz” fold (though somehow he seems to have confused his blintzes with his knishes, a blintz being a kind of rolled pancake, and a knish something more recognizably folded), and in the early 1950s he sought out an obscure paper folder in Japan, named Akira Yoshizawa, and brought his work to Europe.

Legman’s place in the pantheon of paper folding was therefore assured—except that he managed to fall out with many of his fellow paper folders, and so became the black sheep of the family. He resigned from the United States Origami Association, according to his biographer, Mikita Brottman, over an argument about “a badly bent corner,” and David Lister, a retired solicitor from Grimsby who is perhaps the most unlikely but undoubtedly the greatest living Western authority on origami history, remarks, with studied understatement, that “It is unfortunate that Legman often adopted an aggressive personal manner.” A friend, the writer John Clellon Holmes, described Legman as a “psychiatric Genghis Khan.” If Oppenheimer is origami’s mother figure, Legman is undoubtedly the wayward uncle.

And that obscure paper folder, Akira Yoshizawa? Yoshizawa is in fact modern origami’s great-grandfather, the father of the multitude. Born into a family of farmers, Yoshizawa worked as a draftsman and studied for the Buddhist priesthood before deciding to pursue origami full-time, surviving by selling condiments and snacks door-to-door. Already age forty, in 1951 he was invited by the editor of a prestigious Japanese pictorial magazine, Asahi Graph—similar to Life magazine in the USA—to produce some models to be photographed for publication. Finally, his reputation began to spread. In 1953 he was contacted by Legman, who helped organize an exhibition of his work in Amsterdam, and in 1954 Yoshizawa published his first book, Atarashi Origami Gejijutsu (New Paper-Folding Art). With fellow origami artist Sam Randlett he established the internationally accepted system of notation for origami folds, the Yoshizawa-Randlett system, with its now-familiar little arrows and dotted lines; he also developed the technique of so-called wet folding, which is exactly as its name suggests; and, most important, he produced models of exquisite beauty. His trademark gorillas are a wonder: perfectly proportioned baby Kongs. He was, simply, a great artist.

Paper-folded dragon

And to complete this strange family picture? The bespectacled, balding South African stage illusionist Robert Harbin: modern origami’s father figure. I should perhaps admit an interest here: the first book I ever bought, long before I bought a novel or any slim volume of verse, was one of Harbin’s guides to origami, Origami 3: The Art of Paper-Folding (1972). I’d missed Origami 1 and Origami 2, but as a teenager I seem to have been attracted to the idea of being able to make creatures out of almost nothing, and with no tools, using only my hands—Origami 3 features a couple of startlingly bright green turtles on the cover, crawling across sand as if they’ve just emerged, fresh spawned, from the primordial swamp—and I was inspired also by Harbin’s TV series, Origami, which used to be on when I got home from school.

Harbin was a conjuror who had become fascinated by paper folding as a kind of trick or show, and whose Paper Magic (1956) was one of the pioneering English works on the subject. He got to know Legman and Oppenheimer, corresponded with Yoshizawa, and became the first president of the British Origami Society—he was an authority—but on television he would simply sit at a table, address the camera familiarly and directly, and talk you through the making of a model, step-by-step. He made it sound easy. Watching Harbin I think I realized that paper folding was in some profound way about making things smaller and simpler, and as a teenager I perhaps had the sense, like a lot of teenagers, that I myself wished to be smaller and simpler, to be able to disappear almost, to enfold and enclose myself and to become something different, and of the essence. Unfortunately, although I had Harbin’s book as a guide, I soon discovered that there was no actual origami paper to be had in Essex in the 1970s. Indeed, in our house, there was hardly any paper to be had at all. My father would occasionally smuggle some A4 sheets home from work, and I would cut these down into squares, but it was too thick and too white to be able to make satisfactory models. I eventually found that carbon paper was much better for folding, except that it left your hands blue-black; so throughout the mid-1970s I fought a long and lonely battle with paper, attempting to fold mucky, flimsy dolphins, and birds, and dogs, and weird little pointless boxes. I never could do Harbin’s turtle.

Oppenheimer, Legman, Yoshizawa, Harbin: these are just some of the characters in the strange history of paper folding. There are many others, as amazing as they are unexpected: Miguel de Unamuno, the Spanish novelist and philosopher, who loved to fold “parajitas,” little birds; Adolfo Cerceda, the Argentinian professional knife thrower turned paper folder; the matronly and massively prolific Florence Temko, every beginning folder’s best friend; polymathematic Martin Gardner, the popular science writer who promoted origami through his long-running column in Scientific American; dear Alfred Bestall, the children’s illustrator and cartoonist who drew Rupert Bear for the Daily Express, and whose Rupert annuals traditionally included an origami model; the magnificently prosaic John Smith, who in the 1970s invented what is now called Pureland origami, which allows only for the simplest of folds; the incredible Robert Lang, the onetime research scientist turned full-time paper folder and one of the new wave of precision paper folders to emerge in the 1980s and 1990s, who works with laser cutters to make his folds, and designs his work using his own specialist origami software; and of course Sadako Sasaki, the little girl who survived the bombing of Hiroshima, but who developed leukemia, caused by the radiation, and who in the hospital, dying, folded a thousand paper cranes, that they might bring her good luck, and whose friends and classmates built a memorial for her in the Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima, where to this day people fold paper cranes to honor her memory.

But enough about the people. What about the paper? The first thing to be said about origami paper is that it’s not ordinary paper, as I discovered to my cost as a teenager. Ordinary paper is usually rectangular, while origami paper is usually square. (David Lister suggests that origami paper is square not merely because a square has unique geometrical properties—what doesn’t?—but because a square always has the same geometrical proportions, and so patterns and diagrams for folding square paper are easily transmissible; origami’s fundamental squareness, one might say, is the reason for its popularity.) Ordinary paper is white; origami paper comes in many colors. Ordinary paper can be bought by the ream at stationery stores; origami paper is available mostly in Japan, or on the Internet. In the West, the most widely available origami paper is kami, which comes in packs of thin, square, uncoated paper, six-inch or ten-inch, colored on one side and white on the other. This is what we think of as traditional origami paper. And as with most traditions, it’s about as traditional as a ploughman’s lunch, Christmas trees—or, indeed, Christmas itself. (Everyone knows it was the Victorians who invented Christmas, but it might be more accurate to say that it was the Victorians who invented Christmas as a cheap pulp Saturnalia, complete with cards, puzzles, board games and decorations. Paper makes Christmas. And so does origami: the entomologist Alice Gray, a curator at the American Museum of Natural History, who was a friend of Lillian Oppenheimer’s, used to dress the Christmas tree at the museum with origami models, and the origami Christmas tree is now a museum tradition of long standing. Gray’s book The Magic of Origami (1977) contains an excellent section on origami Christmas models, though the great Florence Temko trumps it with her all-inclusive Origami Holiday Decorations (2003), which contains paper decorations suitable also for Hanukkah and Kwanzaa.)

The nontraditional traditional Western kami paper—the word in Japanese can refer to any kind of paper—seems to have been developed for use by children, and perhaps derives from the style of paper used by the Froebel kindergartens. Friedrich Froebel was a nineteenth-century German educationalist who believed in educating children through play, using a number of what he called “gifts” and “occupations.” The gifts consisted of wooden blocks and balls and sticks, and the occupations were exercises in understanding the properties of solids and surfaces and lines, using the gifts and other materials including beans, seeds, pebbles and pieces of string. Papierfalten—paper folding—was one of the occupations designed to teach children about surfaces. An enthusiastic account of the newfangled Froebelian methods in Dickens’s Household Words in 1855 noted in particular that “By cutting paper, patterns are produced in the Infant Garden that would often, through the work of very little hands, be received in schools of design with acclamation.” Froebel kindergartens usually used paper that was blue on one side and white on the other, the contrast being useful because it aided the understanding of geometry and shape, and useful also because it was cheaper to have one side uncolored. The first Japanese Froebel kindergarten was opened in Tokyo in 1876, and the idea of the gifts and occupations—including paper folding—influenced the development of Japanese educational practice and philosophy. In an example of what one might call reverse-fold colonialism, origami paper has therefore made a long journey first from Germany to Japan, and then from Japan back to the West.

Serious paper folders, like all serious people—except writers, who are often content with pens and backs of envelopes—tend to use specialist equipment in order to practice their art. Most specialist paper used for origami is made not of wood pulp, but of other plant fibers, which haven’t been brutally chemically mashed and ground, and which don’t contain lignin, the chemical compound that usefully binds and strengthens wood cells but which tends to make paper turn yellow and brittle. Classic papers for origami include Japanese kozo and gampi, Korean hanji, lokta from Nepal and unryu from Thailand. A particular favorite among European paper folders is Zanders Elephant Hide, which weighs in at around 110 gsm (compared to the standard 70–80 gsm weight of copier paper and 120 gsm for card stock) and has a rugged, parchmentlike texture, high tensile strength, and a profound memory for creases, which means a fold will last forever. I have about a dozen sheets that at £10 (approximately $16) a pop I’m too scared to fold. When I die, I want to be wrapped in my Zanders Elephant Hide and buried in a paper coffin (an Ecopod, produced by a company in Brighton, made from recycled newspapers and finished with paper made from 100 percent mulberry pulp, each coffin equipped with carrying straps and a calico mattress; I’m going for the Indian red, screen-printed with an Aztec Sun). To create Yoshizawa-style soft creases and curves, you need to wet-fold, which requires a certain kind of paper prepared with a lot of sizing that dissolves when wet, making the paper malleable and soft but not soggy. A good cheap wet-folding paper is standard watercolor paper, which you can dampen with a cloth and then fold as you would normally. For folding intricate models, Robert Lang has a cheap DIY method for making springy, malleable paper, which requires a roll of tinfoil, some tissue paper and a can of artist’s spray adhesive. Lang calls this paper “tissue foil.” Once you go to tissue foil there’s no going back.

But there is going over. For the foolhardy and the very intrepid, extending and exploring the full possibilities of paper folding might seem logically to lead to paper cutting, though in Manichean fashion, paper cutting is also, logically, the opposite of paper folding: a fearful symmetry. Paper folding decreases area; paper cutting increases perimeter. Paper folding honors unity; paper cutting enacts separation. Just as paper folding evolved in similar forms throughout the world, so paper cutting has a global history of great variations and similarities, a global history that is yet to be written. The Japanese have kirigami. The Chinese have jian zhi. The Spanish, papel picado. In Germany, Scherenschnitte. In Poland, wycinananki. India has sanjhi, and a Jewish family traditionally has about the home both a ketubah, a paper-cut marriage contract, and a mizrach, a paper-cut wall plaque indicating the direction of prayer. These are all traditional forms and practices. One of the most accomplished contemporary paper cutters, Rob Ryan—whose work has graced Elle magazine, Vogue, book covers and Erasure’s neglected album Nightbird—explains the appeal of the form:

To me, papercutting means that everything is stripped down as much as possible. There is no tone, no variation of colour, no pencil mark, no brush strokes. There is only one piece of paper, broken into by knives; within this is the picture, the message, the story, written and traced in silhouette . . . We all really share only one story, and my work tells that story over and over.

Another artist who told one story over and over was Hans Christian Andersen. Renowned, obviously, for writing fairy tales, Andersen was also an obsessive paper cutter. About 250 of his paper cuttings have survived: unique in style and extraordinary in range, they deserve to be as well known as his writing. When Andersen was a child, his father made him a paper toy theater, with paper puppets, and in his autobiography Andersen writes that his “greatest delight” was making clothes for these puppets. In a sense, it became his life’s work: fashioning paper as he refashioned stories. Andersen—lowly born, self-obsessed, forever craving acceptance, and who never married, never had children, never even owned a house, and indeed seemed barely able to function as a normal human being—loved above all to perform his stories for an audience. As he spoke he would simultaneously cut out paper figures to illustrate what he was saying, a kind of paper performance art. One contemporary, describing such an event, recalled that “When he had finished his tale, he would spread a whole string of ballet dancers in front of us. Andersen would be delighted with the success of his work. He enjoyed our praise of it more than the impression made on us by his story.” The paper cuts were perhaps his in a way the stories could never be. Indeed, in one of his sad little poems, Andersen reflected, “In Andersen’s paper-cuts you see/His poetry!” How true! His paper cuts feature stylized swans, cinch-waisted dancers, hoop-earringed ghouls, grinning skulls, misshapen hearts, gibbets and palaces, the very stuff of his folk-tales, but made entirely, vividly his own.

Andersen always used white paper for his cutouts: it’s what gives them their ghostly quality, like intimations, or photographic negatives of the other world, or of the world of hidden emotions; paper again providing an important bridge into the human interior and our endless unwritten hinterlands. In his methods and in his fantastic style Andersen was, in effect, an antisilhouettist. Silhouettes, or shadow portraits, as they were sometimes known—or shadow pictures, shades, profile miniatures, shadowgraphs, skiagrams, scissortypes, black shades or, simply, likenesses—were the most popular form of portraiture in the eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries. The word “silhouette” derives from the name of the ill-fated minister of finance under Louis XV, Étienne de Silhouette, who attempted to levy taxes on the rich and even to curb royal spending: he lasted all of eight months in his post in 1759. The use of the word “silhouette” to describe black profile portraits may derive from the idea of Monsieur Silhouette as a skinflint, and thus a silhouette as a cheap form of portraiture—à la silhouette, on the cheap—or it may refer to M. Silhouette’s fleeting tenure as minister, or perhaps to the fact that he liked to cut profiles himself. Whatever the etymology of the word, the art of the silhouette can in fact be traced back long before poor Silhouette, to the black profiles on Greek pottery (the very first silhouette was often said to have been made by Dibutade, the “Maid of Corinth,” the daughter of a Corinthian potter who, according to Pliny the Elder, traced her profile as it was cast by candlelight on a wall).

The physiognomist Johann Kaspar Lavater was a great enthusiast for silhouettes, as he was a great enthusiast for many other things, describing them in his bestselling Physiognomische Fragmente zur Beförderung der Menschenkenntnis und Menschenliebe (1775–78) (Essays on Physiognomy; Designed to Promote the Knowledge and the Lore of Mankind) as the “truest representation that can be given of man.” As well as being a great enthusiast—or perhaps because of it—Lavater was also a terrible exaggerator. Despite his meticulous instructions and recommendations for the creation of perfect machine-cut paper profiles, using a pantograph and particular paper (“the shade should be taken on post paper, or rather on thin oil paper, well-dried”), the silhouette soon became a cheap and cheerful sideshow entertainment, a vulgar art form knocked off in a couple of minutes by hawkers and hucksters. Indeed, the art of paper-cut silhouettes eventually became so lowly regarded that the collector Desmond Coke, in his book The Art of Silhouette (1913), was at great pains to point out—in strained italics—that “The best silhouettists never touched a pair of scissors.” Coke notes that the “quartette supreme” of eighteenth-century silhouettists—John Miers, Isabella Robinson Beetham, Charles Rosenberg and A. Charles of the Strand—all painted their portraits on card, glass or plaster, though even Coke has to admit that the most famous silhouettist of all time, Auguste Amant Constance Fidèle Edouart, did indeed work with lowly scissors and paper.

Edouart was the Johnny Cash of paper cutters, a wayfaring stranger who called himself the “black shade man.” “The beauty of those Likenesses,” he wrote, “consists in preserving the dead black, of which the paper is composed.” (Research at the National Portrait Gallery on Edouart’s work shows that he used paper treated with bone black and Prussian blue, the blue to make the black seem blacker.) Edouart arrived in England from France in 1814, and after more than a decade perfecting his art and sharpening his wits—his portrait of William Buckland and his wife and son examining Buckland’s natural history collection (c. 1828) is typically whimsical—he traveled on to the United States. Edouart’s method was consistent and simple: he would fold his paper once, with the black side in, so that two copies would be produced, one of which he would keep for reference in an album, and then he would make a quick sketch, pick up his embroidery scissors—small, sharp and with long handles—and begin to cut. On completion he would sometimes touch up the edges of the paper to accentuate the contrast between the black and the white mount, or paste the silhouettes onto an appropriate lithographed background (images of drawing rooms, battlefields, seascapes). To his great delight—he was not a modest man—Edouart made it in America. He was a silhouettist superstar. But as he was returning to England in 1849, tragedy struck. The ship he was traveling on, the Oneida, hit a fierce storm off the coast of Guernsey, and although Edouart was saved, almost all of his precious albums were lost: tens of thousands of silhouettes drowned in the depths of Vazon Bay, black on black. It’s said that he never cut silhouettes again. With the invention of photography the industry would anyway soon come to an end, though of course as silhouettes disappeared, the paper remained: William Henry Fox Talbot’s early “photogenic” method of producing photographic images was effectively a form of paper photography.

Both before and after photography there are many other paper arts and crafts, some of them half forgotten, many of them regarded merely as quaint, that combine folding and cutting and yet are neither: decoupage, embossing, quilling and paper cast as bas-relief. The patron saint of paper craft in all its bastard forms is, or certainly should be, the wonderful Mary Granville Pendarves Delany, friend of Handel, friend of Swift, and, one suspects, someone who would have been a very good friend of Lillian Oppenheimer. The story of Mrs. Delany’s discovery, and her self-discovery, are well known. In 1772, elderly, widowed, but still lively as a grig, she was staying at Bulstrode, in Buckinghamshire, the estate of her friend the Dowager Duchess of Portland. One morning, so the story goes, Mrs. Delany noticed the similarity in color between a piece of discarded paper and a geranium petal, whereupon she took up a pair of scissors and began to make a paper flower, which she then pasted and mounted onto black paper. Instantly, she had invented a new art form. She was seventy-two years old, but not unaware of her accomplishment: “I have invented a new way of imitating flowers,” she wrote excitedly to her niece. She called it “paper-mosaick.” Over the next sixteen years Mrs. Delany continued to work with scissors and tweezers and bodkin to make more and more of her paper flowers, almost a thousand of them, collecting them alphabetically in albums, which she named her Flora Delanica. The images—“intense and vaginal,” according to one of her recent biographers, full of “precision and truth,” according to Horace Walpole—are painstakingly composed from tiny pieces of rag paper painted with watercolor and pasted onto pitch-black paper using flour and water. As a child Mrs. Delany had been taught the art and craft of making paper shades, or silhouettes, but with her paper flowers she transformed shades into color, and turned man-made paper back into the botanical.

Mrs. Delany’s flowers have long outlived her. Her work can be seen today at the British Museum, and is periodically rediscovered by artists, writers and feminists, though Germaine Greer dismisses them entirely as “yet more evidence that, for centuries, women have been kept busy wasting their time.” Greer hits the nail on the head but entirely misses the point. Paper, which derives of course from the word “papyrus,” the Latinized Greek name of a plant called by the Egyptians bublos, which gives us the Greek biblion, and which in turn gives us the Bible, is forever reminding us that we live in the land of darkness and the shadow of death, and that we shall all be changed, for this corruptible must put on incorruption, and this mortal must put on immortality. Is paper art a waste of time? Yes, absolutely. Of course. What isn’t?