It is a single sheet of paper, with a British government crest at its head, containing three short, typewritten paragraphs, two handwritten signatures, and beneath the signatures a date, “September 30, 1938.” It is probably the most famous piece of paper in twentieth-century history. It reads:

We, the German Führer and Chancellor, and the British Prime Minister, have had a further meeting today and are agreed in recognising that the question of Anglo-German relations is of the first importance for our two countries and for Europe.

We regard the agreement signed last night and the Anglo-German Naval Agreement as symbolic of the desire of our two peoples never to go to war with one another again.

We are resolved that the method of consultation shall be the method adopted to deal with any other questions that may concern our two countries, and we are determined to continue our efforts to remove possible sources of difference, and thus to contribute to assure the peace of Europe.

Neville Chamberlain arrived back from Munich at Heston Aerodrome in west London, on British Airways Lockheed 14 G-AFGN, just before 6 p.m. on Friday, September 30, 1938. It had been his third trip to Germany in just over two weeks. Europe was in crisis and war looked imminent. After the Anschluss of March 1938, Hitler’s territorial claims had only increased: he had set a deadline of September 28 for the Czech government to secede the Sudetenland, its border territories, and his widely reported speech at the Berlin Sportspalast on September 26, according to his biographer Alan Bullock, was “a masterpiece of invective which even he never surpassed.” In Britain, the Home Office had already posted to every household a handbook on protection against air raids. Gas masks had been issued. Trenches were being dug, and air raid shelters constructed. According to one historian, R.A.C. Parker, “On the morning of 28 September the inhabitants of British cities expected to endure German bombing within days or even hours.” The Munich Agreement, signed in the early hours of September 30 by Germany, France, Italy and the United Kingdom, granting Germany the right to occupy the Sudetenland, in return for agreeing to allow an international commission to oversee future territorial claims, appeared the best possible outcome. It looked as though war had been averted.

So, Chamberlain alighted from the plane. Sixty-nine years old, smart, sprightly and clearly exhilarated. The large crowd gathered to meet him gave him three cheers. He shook hands with his cabinet colleagues, was welcomed by the lord mayor of London and then made a short statement. First of all he thanked the British people for their letters—”letters of support, and approval, and gratitude; I cannot tell you what an encouragement that has been to me.” Then he went on:

Next I want to say that the settlement of the Czechoslovakian problem, which has now been achieved is, in my view, only the prelude to a larger settlement in which all Europe may find peace. This morning I had another talk with the German Chancellor, Herr Hitler, and here is the paper which bears his name upon it as well as mine. Some of you, perhaps, have already heard what it contains but I would just like to read it to you.

He brandished the piece of paper, and read it aloud. There were more cheers. Indeed, crowds cheered him all the way on his journey to Buckingham Palace, in heavy rain, where he met King George VI, before finally returning to Downing Street, where he was persuaded to lean out of a first-floor window and declare to the many gathered well-wishers, “My good friends: this is the second time in our history that there has come back to Downing Street from Germany peace with honour. I believe it is peace for our time.” Letters of thanks and telegrams came flooding in from all over the world—tens of thousands of them in just a few days. “Good man,” cabled President Franklin D. Roosevelt. There were plans for statues to be erected in his honor. Streets were renamed after him, scholarships endowed in his name: he was a hero. “No conqueror returning from a victory on the battlefield,” declared The Times on October 1, “has come home adorned with nobler laurels.” By 1940 all the laurels had turned to barbs: Chamberlain was regarded by many as a guilty man, an appeaser.

He had been betrayed by a piece of paper; he had trusted in words, and words had run away with him. In the debate on the Munich Agreement on October 6 in the House of Commons he was already seeking to excuse himself, explaining that he had spoken from the Downing Street window “in a moment of some emotion, after a long and exhausting day, after I had driven through miles of excited, enthusiastic cheering people,” and that people should “not read into those words more than they were intended to convey.” Too late, because Hitler already knew exactly what such words conveyed, and how much they were worth: absolutely nothing.

Chamberlain’s piece of paper had been signed after the official meetings in Munich in the early hours of the morning on September 30, at Hitler’s private flat in Prinzregentenplatz. Chamberlain had foreseen the importance of returning to England with something more tangible than a mere verbal promise about Germany’s territorial ambitions, and had taken the precaution of bringing a typewritten statement with him. He later recalled that when he presented the piece of paper to Hitler, the Führer “frequently ejaculated ‘ja, ja’, and at the end he said, ‘yes, I will certainly sign it; when shall we do it?’ I said ‘now,’ and we went at once to the writing-table, and put our signatures to the two copies which I had brought with me.” Chamberlain was so delighted to have secured the signature that according to one observer, he patted his breast pocket and exclaimed, “I’ve got it!” He’d had it. Chamberlain was—in the words of a recent biographer, Robert Self, “the quintessential rationalist.” Hitler, alas, was not. Hitler was the Künstlerpolitiker, the artist politician, a rhetorician, someone for whom words could mean what he wanted, when he wanted. “For him,” writes his biographer Ian Kershaw, “the document was meaningless.” Indeed, when the German foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, complained to Hitler about signing the paper, the Führer told him not to worry about it: “That piece of paper is of no further significance whatever.” It is of further significance, but not of the significance that Chamberlain might have hoped. It remains a sign of betrayal, a symbol of the moment at which the covenant is broken, and a piece of paper is revealed as exactly what it is, just a piece of paper. Duff Cooper, First Lord of the Admiralty, and one of Chamberlain’s fiercest critics, resigned the day after the Munich Agreement, and later famously referred to Chamberlain’s document as “that miserable scrap of paper.” During the course of the Second World War, paper was to become more miserable still.

There were, of course, all of the various military uses of paper. Paper has been used as a weapon and in war for thousands of years—not least as a means of funding wars. When Queen Anne, for example, wished to raise money for the long-running War of the Spanish Succession in the early eighteenth century, Parliament obligingly introduced a tax on paper, one of the so-called taxes on knowledge, a tax that was steadily increased until being finally abolished in 1861. From taxes to bomber kites to war games to gun cartridge casings to uniforms and armor, paper has been used in every conceivable fashion both to inflict torture and to protect from pain. In China, during the late Tang Dynasty (AD 618–907), governor Xu Shang trained a notorious elite army of a thousand men who were equipped with armor made of thick layers of paper; they were invincible. (In Essex in the 1970s we used to make v-shaped paper pellets from blotting paper, which was heavy, and which stung, and which left a satisfying inky stain. Anyone caught firing paper bullets by one particularly cruel teacher was punished with what he called “the paper shower,” which involved the entire class tearing pages from their exercise books, ripping them into tiny shreds and scattering them on the floor for the offenders to pick up, crawling on our hands and knees between and beneath the desks, while the rest of the class was encouraged to kick us. It was, I suppose, a lesson in retributive justice: a life for a life, an eye for an eye, and miserable scraps of paper for miserable scraps of paper. A harsh lesson, and a terrible waste: many of us were put off both education and any kind of white-collar paper-shuffling jobs for life; who needed it?) During the Second World War, paper was used to make disposable gas tanks and protective window stripes—everybody needed it. It was a precious commodity. In Britain, a National Salvage Campaign was established in 1940; in America, the Salvage for Victory campaign began in 1942. Paper recycling was a patriotic duty. Indeed, so concerned was the British Records Association that important documents and books might be destroyed in the rush to recycle that it published a leaflet encouraging the public to “Look Before You Throw.”

Elsewhere, the aim was to throw to get people to look. In early autumn 1939, the Germans dropped paper leaflets on the French troops stationed along the Maginot Line—they already had what one might reasonably call “form” in leaflet bombing, having first taken to the air to scatter pamphlets during World War I. Golden-hued and shaped as maple leaves, the leaflets featured a death’s-head image and a message beautifully expressed, almost like a poem: “Automne: Les feuilles tombent/Nous tomberons comme elles./Les feuilles meurent parce que Dieu le veut/Mais nous, nous tombons parce que les/Anglais le veulent” (Autumn: The leaves are falling. We will fall like them. The leaves die because God wills it, but we fall because the English will it). The British were also busy spreading rumors and information of their own: psychological warfare units were equipped with mobile printing presses to provide instant responses and rebuttals to Nazi attacks and propaganda. From the first recorded aerial drop of propaganda leaflets during the siege of Paris in 1870 to the wars and conflicts of today, it is impossible to calculate exactly how much paper has been used as a psyop tool, although Reginald Auckland, the world’s leading authority on aerial-dropped leaflets, and the editor for many years of Falling Leaf, the strange-but-true magazine of the Psywar Society, calculated that during the Vietnam War alone, 6,245,200,000 pieces of paper were dropped from bombers and helicopters:

So lavish were the propagandists with the paper and so enthusiastic were the crews that villages with populations of about one hundred were receiving 100,000 leaflets at one drop. Leaflets were seen everywhere in Vietnam: for wrapping food, in restaurants for wiping chopsticks or spoons, as wallpaper to block holes in poorer homes and, of course, as lavatory paper.

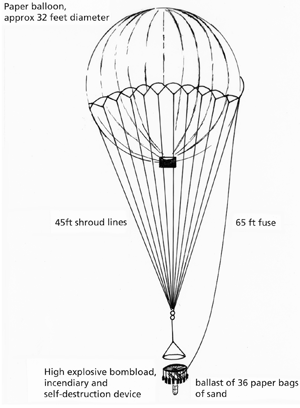

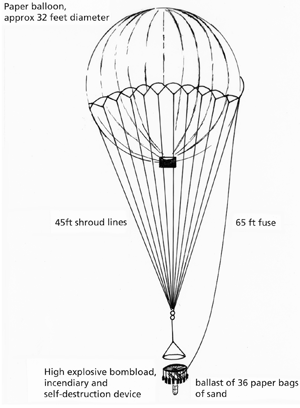

The Japanese, meanwhile, with their long and proud history of paper craft, had no intention of their paper weaponry ending up as toilet tissue. After the American Doolittle air raid on Tokyo and other Japanese cities of April 1942, the Japanese government under Prime Minister Hideki Tojo made elaborate plans for retribution, including the hot-air balloon bombing of America. The balloons, with a diameter of ten meters, loaded with incendiary bombs, were made of koso paper layered into sheets and glued into sections, pasted with calcium chloride and shaped into giant balls. According to Therese Weber, in her book The Language of Paper: A History of 2000 Years (2007), during the Second World War a Japanese master papermaker reported that “most papermakers in the country were making paper for military use.” But to no great effect. A few of the big paper balloons reached the west coast of California. No real damage was done.

Japanese incendiary balloon

But in Europe, paper caused havoc. In The Truce (1963), his book about his return home from Auschwitz—the companion volume to If This Is a Man (1947)—Primo Levi describes in detail how a culture of death and destruction was fed and fattened on paperwork. He candidly admits that “printed paper is a vice of mine,” but clearly there are vices and there are vices, and during the war Levi, like millions of others, became trapped in the grip of a genocidal machine fueled by paper; this was not a paper vice, it was a paper factory, a smelting works, an industrial pulp plant. The definitive, and utterly shocking, work on Nazi technocracy and bureaucracy is Die restlose Erfassung (1984) by two German investigative journalists, Götz Aly and Karl-Heinz Roth—translated into English as The Nazi Census (2004)—whose data-dense argument is perhaps best summed up in the words of another historian writing about the period, John Tovey: “Passports, identification cards, population registries, and visible distinguishing marks intended to keep watch on and control the movements of Germany’s population came to constitute an interlocking if not flawless system of registration and tracking. These mechanisms facilitated the task of locating and monitoring Jews, with the ultimate result that they were available for extermination.” A more recent tragic example of the casual link between documentation and death can be found in Africa, in Rwanda in 1994, with the mass slaughter of the Tutsi population by Hutu militia. A political scientist, Timothy Longman, sums up the disturbingly simple equation at work there: “Since every Rwandan was required to carry an identity card, people who guarded barricades demanded that everyone show their cards before being allowed to pass. Those with ‘Tutsi’ marked on their cards were generally killed on the spot.”

In the transit camp at Katowice, Primo Levi was employed in checking for lice, and was required to record both the number of lice and the names of the sufferers on endless forms. He admits that he was delighted eventually to be granted his own special form, a propusk, “a permit of somewhat homely appearance” that enabled him occasionally to leave the camp, “a sign of social distinction.” In all his books about his wartime experiences, Levi describes a world thick with paper and its implications. He watches the Red Army returning home from the Front, for example, arriving on trains, washing in freezing-cold water, and rolling cigarettes using sheets of Pravda. When he starts selling goods at a local market with a friend, the first thing they sell—”at the first attempt . . . without bargaining”—is a pen, and when finally he is about to be released from Katowice a Dr. Danchenko ominously arrives with “two sheets of paper”:

We were amazed to learn that the Command expected from us two declarations of thanks for the humanity and correctness with which we had been treated at Katowice . . . Danchenko in turn took out two testimonials written in a beautiful hand on two sheets of lined paper, evidently torn from an exercise book. My testimonial declared with unconstrained generosity that “Primo Levi, doctor of medicine, of Turin, has given able and assiduous help to the Surgery of this Command for four months, and in this manner has merited the gratitude of all the workers of the world.”

With this testimonial Levi is free, though his long journey home presents yet more paper obstacles:

The local stationmaster, for example, had demanded our travel warrant, which notoriously did not exist; Gottlieb told him that he was going to pick it up, and entered the telegraph office nearby, where he fabricated one in a few moments, written in the most convincing of official jargon, on some scrap of paper which he so plastered with stamps, seals and illegible signatures as to make it as holy and venerable as an authentic emanation from the Top.

In the camps, Levi needed paper to survive—in If This Is a Man he describes being involved in the theft of some graph paper, to be used as a form of barter and currency—and after the war he remained dependent upon it. In a celebrated passage in The Periodic Table (1975) he describes how the atoms and molecules in his body urge him to make his mark: “It is that which at this instant, issuing out of a labyrinthine tangle of yeses and nos, makes my hand run along a certain path on the paper, mark it with these volutes that are signs: a double snap, up and down, between two levels of energy, guides this hand of mine to impress on the paper this dot, here, this one.”

Paper is a tyrant and an oppressor, therefore, but also a savior and a means of witness. This remains undoubtedly the greatest paper paradox of all. (Like Levi, the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish famously explores these two sides of paper in his work, perhaps most famously in his poem “Identity Card”: “Write down/I am an Arab/& my I.D. card number is 50,000.”) Paper, our preeminent technology of the self, is both imposed upon us from outside, by others and by the state, constructing our identity for us and through us, but is also the means by which we shape ourselves, and become individuals, interiorized, unique and distinct. Paper makes us legible: it also makes us erasable. Memorable: dispensable. Priceless: worthless. Living: dead. (The poet Eugenio Montale has a poem, “The Decline of Values,” which he wrote down, of course, and which is published in a book, and which reads, “Tear up your pages, throw them in a sewer,/take no degree in anything,/and you will be able to say that you were/perhaps alive for a moment or an instant.”)

The sociologist Anthony Giddens, in Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age (1991)—one of those breathtaking books written in the kind of jargon-rich prose that one can only sniff and inhale rather than actually digest and understand, and which seems therefore all the more profound, like the evocative smell of perfume, or cigar smoke at the scene of a crime—suggests that “In the post-traditional order of modernity, and against the backdrop of new forms of mediated experience, self-identity becomes a reflexively organised endeavour. The reflexive project of the self, which consists in the sustaining of coherent, yet continuously revised, biographical narratives, takes place in the context of multiple choice as filtered through abstract systems”—and, one would want to add, rather plainly, waving away the whiff of cigar smoke, on paper. Paper is our primary method of identification and self-identification. Or in Giddenspeak, it is one of the key mechanisms of our reflexively organized posttraditional endeavor. I am my documents. Passports are an obvious case in point.

My passport—which is, still, a paper passport, though of a highly evolved kind, rich and thick with advanced print technology and special inks and security threads, and even a little radio frequency identification chip embedded in the back cover—reveals certain information about me as an individual, but also about me as a member of a group, or a nation. It also usefully assumes and testifies to the fact that I am what philosophers might call a unitary continuing entity—a person, in other words—and can therefore be held responsible for past actions. (Though it should be admitted that one of the great pleasures of being a person is pretending not to be a unitary continuing entity, and attempting to achieve states of nonunitary, discontinuous nonentity, by going on holiday, say, or to sleep, or having sex, or enjoying role-playing computer games, or getting drunk, or reading novels, using paper to escape from a passport self. Personally, as a young adult I immersed myself not in drugs or sex or foreign travel, but in the worlds of noir fiction and psychological thrillers, where the protagonists were never what they seemed, or who they said they were: Jim Thompson’s The Killer Inside Me (1952); Georges Simenon’s The Man Who Watched the Trains Go By (1938), Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley novels; and, above all, Frederick Forsyth’s The Day of the Jackal (1971), a shameless celebration of self-aggrandizing self-creation, in which the nameless assassin creates for himself a new identity by stealing a passport and identification papers and having them altered by a forger he meets in a bar in Brussels, and when this hapless forger tries to blackmail him—“The papers you have. My silence costs a thousand pounds”—the Jackal simply kills him with his bare hands. That’s what it meant to be paper-free! That’s what it meant not to be me!)

The origins of the modern passport system are extraordinarily recent, though there have long been various documents that seek to guarantee safe conduct: indeed, the historian Michael Clanchy notes that “by the second half of the thirteenth century it was imprudent for anybody to wander far from his village without some form of identification in writing”; in some villages in Ireland, where I live, it is imprudent still. It wasn’t until the nineteenth century that the passport as we know it today—a document issued to a single individual, certifying their identity and securing their right to travel, available on application and not only for diplomatic, trade or military purposes—came into being, and the now familiar pocket-sized, durable passport between cardboard covers was only introduced in the early twentieth century, not just as a guarantee of free travel but as a document of national identity, or, in rare cases, of non-national identity. (Nansen passports, introduced in 1922, were initially used to aid the Russians who had fled from the Bolsheviks, and were so named after the League of Nations’ High Commissioner for Refugees, the Norwegian explorer Frijdtof Nansen, who recognized the need for the stateless to be able to cross borders and frontiers.) In his Devil’s Dictionary (1911) the satirist Ambrose Bierce defined a passport as “A document treacherously inflicted upon a citizen going abroad, exposing him as an alien and pointing him out for special reprobation and outrage.” To possess a passport may be to expose oneself to certain forms of reprobation and outrage, but not to have a passport, or to be paperless, can be an altogether more terrifying plight: in France, until this year, 2012, “sans-papiers,” illegal immigrants, could be held in police custody for not having the necessary residency papers. Now, instead of custody or imprisonment, they are escorted to the border.

Identity documents, however, have never just been about keeping track of foreigners and constructing paper walls to keep them out. The history of identity documents is in fact related perhaps more profoundly and significantly to the classification and identification of population groups within nations, by the use of censuses, registers and statistical records to enable the collecting of taxes and the enforcing of laws, the imposition of military service and the monitoring and managing of state provision of health care and education. Nation states are built from paper, or to borrow Jacques Derrida’s terms in Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression (1995), “there is no political power without control of the archive, if not of memory,” and this memory, this archive, still remains largely on paper.

Given the long history of the state’s use of paper to identify, track, manage and control its citizens, it’s perhaps no surprise to find that paper archives remain places of controversy and contention. In 1999, for example, thirty-four boxes of documents that had been secured by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa disappeared, including the public record of the commission’s hearings into the previous apartheid state’s chemical and biological warfare program, “Project Coast,” and details of hearings about various criminal investigations. The documents were supposed to have been transferred to the South African National Archives, but had actually been taken into custody by the National Intelligence Agency. It was only after a three-year legal battle waged by the South African History Archive, a freedom-of-information NGO founded by Verne Harris, that the documents were placed in the National Archives, with many of them now in the public domain.

Putting documents into the public domain is not as easy as it sounds: as a source of identity and memory, paper presents some obvious challenges and difficulties. Such as, it decays and can be destroyed. Or shredded. In Stasiland: Stories from Behind the Berlin Wall (2003), Anna Funder investigates the legacy of the GDR regime, which required its members “to sign pledges of allegiance that looked like marriage certificates, confiscated children’s birthday cards to their grandparents and typed up inane protocols at desks beneath calendars of large-breasted women.” Funder calculates that at the height of its power, the Stasi, the East German secret police, had 97,000 employees and 173,000 informers, all of them producing paper documents at an alarming—or, rather, a terrified—rate. After the fall of the Berlin Wall many of these documents were shredded: coming to terms with the past means putting them all back together. Funder describes her visit to the Stasi File Authority offices, in a village near Nuremberg, where women are employed to go through the approximately fifteen thousand sacks of shredded files:

The window is wide open, a white curtain moves in the breeze and I am panicked, my heart climbing steps up my chest, because on the desk there are masses and masses of tiny pieces of paper—some in small stacks but others spread out all over. There are so many tatters of paper that the desk is not big enough, and the workers have started to lay them out on top of the filing cabinet as well. The pieces are different sizes, from a fifth of an A4 page to only a couple of centimetres square—and there is nothing, nothing to stop them flying around the room and out the window.

The director of the Stasi File Authority explains the immensity of the task: one worker reconstructs on average ten pages per day; forty workers are employed on the reconstruction; therefore, per year of 250 working days, forty workers reconstruct about 100,000 pages. Each sack contains on average 2,500 pages. Which means that to reconstruct the contents of fifteen thousand sacks will take forty workers . . . approximately 375 years. Of the remaking of many books there is no end.

As individuals, of course, as citizens, or immigrants, refugees, guest workers, travelers or tourists, we don’t have that kind of time to play with. So it’s perhaps no surprise that many of us keep on frantically building our own miniature memory palaces out of paper—from diaries, photographs, newspaper cuttings, certificates, programs, report cards, menus, and all the other shreddable, scrapbookable ephemera of our lives. If the institutional archive is where data on us is kept, our diaries and scrapbooks and photographs are where we keep data on ourselves, our hopes, our dreams and our failures; our very own Legitimationspapiere.