Paper can wrap, contain, protect and preserve all sorts of goods and products, from peanuts to pineapples, and from paint pots to packets of pins. It allows us to transport goods, to handle them safely, to store them, and to draw up ever more complex stock and inventory control systems—and I know, I used to work in Foyle’s bookshop, on the Charing Cross Road in London, where the antiquated system of collecting a voucher for one’s books at one counter, and then paying for them at another, before returning with a carbon copy and a receipt to collect them from the first counter, was absolutely guaranteed to enrage and baffle customers. Paper also allows us to decorate and advertise goods and products, like this book, to make them seem prettier and more desirable than they actually are, and so to sell them to others for more money, an example of paper making paper.

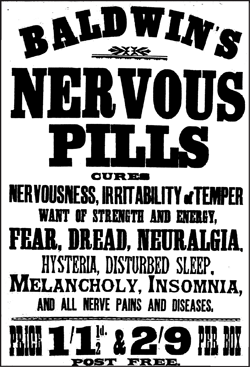

One of the simplest forms of advertisement is the label: abundant, versatile and essential, the label is perhaps the most ubiquitous and yet often the most opulent of all paper forms, existing somewhere between a guarantee, a sign and a promise. So let us begin an investigation of the relationship between paper and advertising by looking at labels. But which labels to look at? The Campbell’s soup labels, immortalized by Andy Warhol? (Which of course represent a nice little trick, a sleight of hand, the making of high art from a low-end high-street paper product, even if Picasso got there first, with his Landscape with Posters (1912), which features depictions of KUB bouillon packaging and Pernod labels, and his Au Bon Marché (1913), made up of a collage of ads.) Or the grand luggage labels of the 1920s and 1930s, by which and through which we might trace the rise and fall of the golden age of Continental travel? Or cigar box labels, with their lingering whiff of luxury? Date box labels? Eat me. Beer, brandy or rum labels? Fruit labels? Parkinsons’ sugar-coated Blood & Stomach Pills labels? The choice is fantastic, bewildering. The great label historian Robert Opie—great, it should be said, not only because he is perhaps the one-and-only label historian, but because he is the historian also of tins and sweets and toys, the true ephemerist’s ephemerist—traces the history of the paper label back to the sixteenth century and forward into infinity and beyond. “During the history of the label,” he writes, “countless millions of designs have been used.” It might be best to start with a label, then. And a labeler.

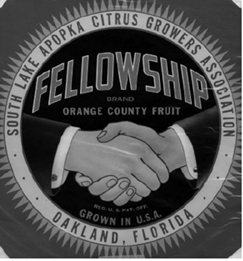

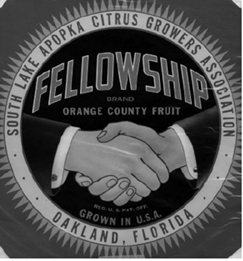

Tissue wrapper used to package citrus fruit

London, 1824. A young boy—maybe eleven, twelve—has been forced, through desperate family circumstances, to leave school and find employment. He is recommended to the owners of Warren’s Blacking warehouse, near Hungerford Stairs, just off the Strand, and in return for a week’s work is paid six or seven shillings, enough to buy himself an old stale pastry for breakfast, a dry sausage and a penny loaf for lunch, and an occasional copy of the Portfolio or some other cheap periodical for amusement. On his way home at night to his dreary lodgings in Camden Town he sometimes visits Covent Garden Market, to stare at the pineapples, or stops off at a sideshow to marvel at the human and animal curiosities: the Fat Pig, the Wild Indian, the Little Lady. And in the warehouse? He spends his days pasting labels onto earthenware pots. One of the labels, designed by no less than George Cruikshank, the “modern Hogarth,” shows a cat, a scruffy tabby, shocked by its reflection in a shiny boot:

Twelve pairs of new Boots, most transcendently grac’d

By WARREN’S fam’d Jet, in a room had been plac’d,

Where twenty-four Cats were accustom’d to meet,

And viewing the Boots they a united squalling

Commenc’d, than the yelling of imps more appalling,

All inmates that forc’d from the house to retreat,

Its shade in the Jet every Cat fiercely fighting—

The row when explain’d, all the hearers delighting

With cheers who proclaim’d it, and ONE CHEER MORE backing

The Mart, 30, Strand, and its reflecting Blacking.

Our poor little label paster is of course Charles Dickens. Recalling his time in the blacking warehouse many years later—“even now, famous and caressed and happy, I often forget in my dreams that I have a dear wife and children; even that I am a man; and wander desolately back to that time in my life”—he describes in detail the exact nature of his employment:

My work was to cover the pots of paste-blacking: first with a piece of oil-paper, and then with a piece of blue paper, to tie them round with a string; and then to clip the paper close and neat all round, until it looked as smart as a pot of ointment from an apothecary’s shop. When a certain number of grosses of pots had attained this pitch of perfection, I was to paste on each a printed label; and then go on again with more pots.

Dickens’s working life begins and ends with paper. On the evening of June 8, 1870, almost fifty years after his stint in the warehouse, having spent the day working on Chapter 23 of his fifteenth novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, in the two-story prefabricated Swiss chalet that served as his studio—his own fancy, miniature warehouse?—in the garden of Gad’s Hill Place, he collapsed, suffering from a stroke, and died twenty-four hours later. The closing words of Chapter 23, written some time that afternoon in bright blue ink, are “and he fell to with an appetite.”

Some writers have peculiar appetites for paper: Rudyard Kipling, for example, who used writing blocks made especially for him, “to an unchanged pattern of large, off-white, blue sheets.” And the high-minded German critic and cultural theorist Walter Benjamin, who was a stationery-obsessive. In a letter in 1927, Benjamin wrote with delight to his friend Alfred Cohn, thanking him for a gift of a blue notebook: “I carry the blue book with me everywhere and speak of nothing else . . . I have discovered that it has the same colours as a certain pretty Chinese porcelain.” “Avoid haphazard writing materials,” Benjamin advises in “One Way Street” (1928), though this is not an admonition he himself seems to have heeded, having used a bewildering range of notebooks and index cards in tandem and in parallel. (Benjamin also collected postcards, photographs, miniature Russian children’s toys and quotations.)

In comparison, Dickens was by no means slapdash—certainly not when compared to the truly haphazard Byron, for example, who wrote Don Juan on the backs of playbills, or the pipe-smokingly self-forgetful Tolkien, who wrote The Lord of the Rings on the backs of undergraduates’ exam papers—but his real appetite was for words rather than for stationery. Indeed, he even had trouble spelling the word: it was, for him, tellingly, always “stationary”; something that was holding him back. Dickens’s furious handwriting, strenuous and aggressive, snarling almost, suggests that he might have written on anything, anywhere, and for anyone: give him the pot, and he’d paste on the label. For his novels he tended to use rough blue paper, not unlike the blue paper used on the Warren’s Blacking pots, which he’d tear in half, writing quickly and firmly on one side only, sometimes using the reverse for corrections and additions. Dickens speaks in a letter of “writing and planning and making notes over an immense number of little bits of paper.” These bits and sheets he called his “slips,” almost as though they were merely receipts or dockets, loading bays for his vast cargo of characters. (Other famous slip-making novelists include Arno Schmidt and Vladimir Nabokov—authors who pieced together their books from boxloads of index cards.)

In this sense, Dickens was the first capitalist writer: his work exists somewhere between an act of labeling, of bookkeeping, and of advertising. Some scholars indeed argue that Dickens’s first published work was some advertising copy, a poem for Warren’s Blacking, not to adorn the pot labels, but for a newspaper advertisement, and there have always been those who have felt that even the novels are just so much puff and blather, like clouds, or Pears soap bubbles. George Orwell, in a famous essay, complained that Dickens’s characters were insubstantial, paper-thin, that you couldn’t have a proper conversation with them, that they had no “mental life”: “Tolstoy’s characters can cross a frontier. Dickens’s can be portrayed on a cigarette-card.” (Orwell is presumably thinking here of the Player’s cigarette cards of his youth, depicting Dickens’s characters, which were first issued in 1912.) There is something “unreal” about Dickens, according to Orwell; and in this also, Dickens was a writer of his time.

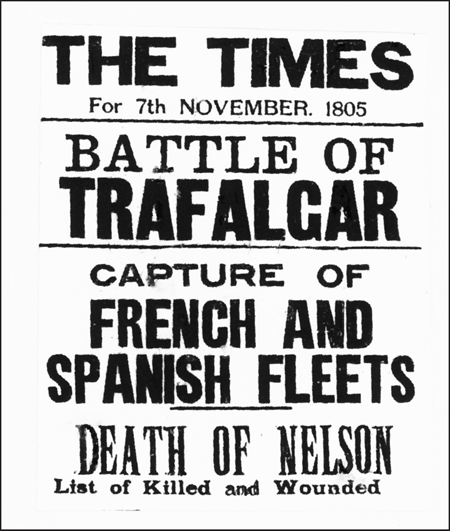

Modern consumer capitalism was born and came to life on paper in the nineteenth century, with public space suddenly colonized as a realm for advertising goods and services. As the cultural critic Raymond Williams was one of the first to note, the true history of advertising begins not with the scraps of papyrus used to announce rewards for the capture and return of runaway slaves in Thebes, or with the handmade paper used to wrap acupuncture needles in China, or even with the illustrated handbills advertising plays, circuses and menageries in the eighteenth century, but with the “institutionalized system of commercial information and persuasion” inaugurated in England by the abolition first of the Advertisement Tax in 1853, and of Stamp Duty in 1855, and by the invention of lithographic printing, with all its lurid possibilities, in 1851. Williams, in his essay “Advertising: The Magic System” (1980), describes what he calls “a highly organized and professional system of magical inducements and satisfactions,” operated by writers and artists and published in newspapers and magazines and displayed on posters and billboards, which produced what he calls “the culture of a confused society.” In the nineteenth century, in the form of advertising, paper came, saw and conquered.

Paper smothered London. In Sketches by “Boz,” Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People (1836), Dickens describes London as “a circus of poster and trade bill, a receptacle for the writings of Pears and Warren’s until we can barely see ourselves underneath. Read this! Read that!” According to the paper historian Dard Hunter, between 1805 and 1835 the annual production of machine-made paper in England rose from 550 tons to almost twenty-five thousand tons: the mills were spewing paper into the atmosphere, and out onto the streets, as the factories were billowing out smoke. The effect was both suffocating and intoxicating. In a popular engraving from 1862, “The Bill Poster’s Dream,” the bill poster sits slumped like a drunk against a lamppost, exhausted, glue pot by his side, examples of his handiwork illuminating the night sky. In an article on “Bill-Sticking” in Household Words (March 1851), Dickens described an old warehouse “which rotting paste and rotting paper had brought down to the condition of an old cheese”:

The forlorn dregs of old posters so encumbered this wreck, that there was no hold for new posters, and the stickers had abandoned the place in despair . . . Here and there, some of the thick rind of the house had peeled off in strips, and fluttered heavily down, littering the street; but, still, below these rents and gashes, layers of decomposing posters showed themselves, as if they were interminable.

Dickens—“The Inimitable”—returns to images of the interminable again in Our Mutual Friend (1865), his last complete novel:

That mysterious paper currency which circulates in London when the wind blows, gyrated here and there and everywhere. Whence can it come, whither can it go? It hangs on every bush, flutters in every tree, is caught flying by the electric wires, haunts every enclosure, drinks at every pump, cowers at every grating, shudders on every plot of grass, seeks rest in vain behind the legions of iron rails.

Paper here is omnipresent, and no paper more omnipresent than Dickens’s own, of course. “I am become incapable of rest,” he wrote to his friend and official biographer John Forster in 1857—as incapable of rest as wind-blown wastepaper. In addition to the novels there were the acres of journalism, and nonfiction, and poetry, and plays, and letters—fourteen thousand of them, no less, in the twelve-volume Pilgrim edition. And this is not even to begin to add up all the paper devoted to actually advertising Dickens, by Dickens and by others: his publishers Bradbury and Evans produced four thousand posters and three hundred thousand handbills to advertise the first number of Little Dorrit alone.

If paper plagued you and followed you everywhere in the nineteenth century, it also pushed and prodded and guided you. This was the age not only of the omnipresent advertisement, of the proliferating periodical, and of vast triple-decker novels, but also of mass-produced ready reckoners, calendars, ledgers and account books. It was, above all, according to The Times in 1874, the “age of timetables.” Route maps and distance charts allowed the ever-expanding population of city dwellers to make sense of their ever-expanding cities. Fielding’s Hackney Coach Rates, first published in 1786, was only the first of a long line—a cab stand—of hackney-coach companions and travelers’ maps, including the magnificently titled The Arbitrator, or Metropolitan Distance Map (1830), The Hackney Carriage Pocket Directory (1832), and William Mogg’s Ten Thousand Cab Fares (1851), designed to guide the traveler safely, and at a fair price, through the metropolis. In Robert Surtees’s 1853 novel Mr. Sponge’s Sporting Tour, the eponymous hero travels everywhere with his Mogg in his pocket, just as Phileas Fogg sets out from Charing Cross with a red-bound copy of Bradshaw’s Continental Rail and Steam Transport and General Guide in Around the World in 80 Days (1873). And even if you weren’t traveling with a pocketful of paper, it accompanied you anyway. The German nobleman Prince Hermann Ludwig Heinrich von Pückler-Muskau, in his Tour of a German Prince (1831–32), described England’s famous walking advertisements: “Formerly people were content to paste them up; now they are ambulant. One man had a pasteboard hat, three times as high as other hats, on which is written in great letters, ‘Boots at twelve shillings a pair—warranted.’ ”

Unwarranted, actually, and alarming. Posters, handbills, billboards, sandwich boards: advertisements were taking over, all over, uninvited and unasked for. In the United States, billboards lined the streets of the nation, like it or not. During the 1860s, the site for the new New York City Post Office was leased to advertisers, with a fence specially erected for bill posters. An article in Collier’s magazine in 1909 complained that “There is no hour of waking life in which we are not besought, incited, or commanded to buy something of somebody. Our morning paper is full of it; our walk to the nearest car bristles with it; the transfer which we take blazons it.” Even in France, where the poster was venerated as a work of art, there were suspicions that this new popular form sought to persuade and influence the masses to act in ways contrary to the laws of nature, and of God. With his brightly colored images of pretty dancing girls, the artist Jules Chéret may have made the poster a thing of beauty and an object of desire—and inspired the work of Toulouse-Lautrec, among others—but the journalist Maurice Talmeyr, in an article entitled “The Age of the Poster” (1896), lamented that such posters exhorted viewers not to “Pray, obey, sacrifice yourself, adore God, fear the master, respect the king,” but rather to “Amuse yourself, preen yourself, feed yourself, go to the theatre, to the ball, to the concert, read novels, drink good beer, buy good bouillon, smoke good cigars, eat good chocolate, go to your carnival, keep yourself fresh, handsome, strong, cheerful, please women, take care of yourself, comb yourself, purge yourself, look after your underwear, your clothes, your teeth, your hands, and take lozenges if you catch cold!”

Paper had caught a cold: it was sick, a sign and a symptom of degeneration. The fear and horror of a world created by paper and made of paper is best summed up in an extraordinary article by John Hollingshead, “The City of Unlimited Paper,” in a December 1857 issue of Dickens’s Household Words, in which Hollingshead imagines London as “New Babylonia”:

Within a certain circle, of which the Royal Exchange is the centre, lie the ruins of a great paper city. Its rulers—solid and substantial as they appear to the eye—are made of paper. They ride in paper carriages; they marry paper wives, and unto them are born paper children; their food is paper, their thoughts are paper, and all they touch is transformed into paper . . . the stately-looking palaces in which they live and trade are built of paper . . . which fall with a single breath. That breath has overtaken them, and they live in the dust.

Echoes here, clearly, of Genesis 2:7, “And the LORD God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul.” And so, one wonders, could the process of decay and decline described by Hollingshead perhaps be reversed? Could a paper city be reborn and redeemed, re-formed from dust?

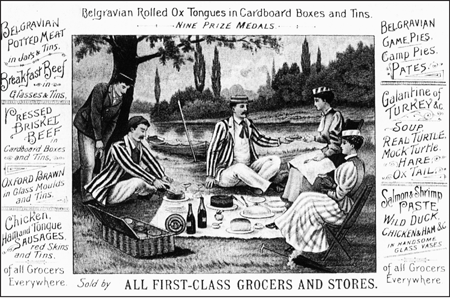

It could. It was. And it is, in the Dublin of James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922). Every degrading paper thing to be found in Dickens—the posters, pamphlets, public papers, private papers, brochures, advertisements, sandwich-board men, and even an advertisement for boot blacking, called “Veribest”—is to be found also in Joyce; but the proliferation of paper in Ulysses is not a threat but the very stuff of life. Ulysses itself might indeed be read as a kind of giant self-advertisement, of the kind described by Joyce’s Leopold Bloom as causing “passers to stop in wonder”: “vertically of maximum visibility . . . horizontally of maximum legibility, and of magnetizing efficacy to arrest involuntary attention, to interest, to convince, to decide.” Bloom himself is of course an advertising canvasser, soliciting ads for the Dublin paper The Freeman, and the novel is literally composed from scraps: “I make notes on the backs of advertisements,” Joyce told a friend in 1917; he also made much use of waistcoat-pocket-sized pieces of paper, large enough to make multiple memos-to-self about Epps’s cocoa, Bushmills whiskey, Guinness, ginger ale, Pears soap and Plumtree’s potted meat, all of which feature largely and exuberantly throughout the novel: “What is home without Plumtree’s Potted Meat?—Incomplete. With it an abode of bliss.” In one extraordinary passage, Bloom imagines an innovative traveling stationery advertisement: “a transparent show cart with two smart girls sitting inside writing letters, copybooks, envelopes, blotting paper. I bet that would have caught on.” Two smart girls and reams of paper: the Irish writer’s fantasy.

A bottle label: author’s private collection

Advertisement for the forerunner of today’s delicatessen, showing the use of glass and tin to increase the storage life of perishable foods

Advertising, then, may be the true curse of paper, its original sin, forever seeking redemption and renewal; the watermark the mark of Cain. As Elizabeth Eisenstein explains in her classic study The Printing Press as an Agent of Change (1979), it was printers who first used advertisements as we understand them today, in increasingly desperate attempts to outdo their rivals: “The art of puffery, the writing of blurbs and other familiar promotional devices were also exploited by early printers who worked aggressively to obtain public recognition for the authors and artists whose products they hoped to sell.” The history of paper is bound up in and emblazoned upon the goods and products and services that it packages and promotes. And just like those goods and products and services—unless saved for posterity in a real or an imaginary museum—it is destined, ultimately, for oblivion. In Posters: A Critical Study of the Development of Poster Design in Continental Europe, England and America (1913), Charles Matlack Price warns that “When a poster fails, its failure is utter and irretrievable, and its inevitable destiny is its consignment to the limbo of waste paper.” At best, perhaps, we can hope to act like King Chulalongkorn of Siam, who collected matchbox labels, and who during a famous visit to London in 1897 would scoop up matchboxes from the gutter, to add to his collection. King Chulalongkorn was what is called a phillumenist. We might prefer to label ourselves cartophilists (collectors of cigarette cards), deltiologists (collectors of postcards), notaphilists (collectors of banknotes), labologists (collectors of beer labels), or even tryroemiophilists (collectors of Camembert cheese labels), but in all cases it is worth bearing in mind this simple piece of advice: “The best way of removing labels from bottles or boxes is to soak them in warm water and wait for them to float off. Some assistance in peeling off the label may be necessary” (Robert Opie, The Art of the Label, 1987). Paper sticks.