In addition to clarifying questions concerning the quality and completeness of title conveyed to a museum, accession procedures should also be structured so that important tax information is readily available. Two issues deserve specific mention: documentation concerning the completion of the gift for tax purposes and documentation concerning the intended use of the gift.

Completion of the Gift. Museum records concerning inter vivos donations should note the date on which each gift is actually placed under the control of the museum, the date on which the deed of gift (or other appropriate written evidence of donative intent) is signed, and the date on which the gift is accepted by the museum. Questions can arise between the donor and the Internal Revenue Service concerning the year in which a charitable gift was made, and copies of museum records may be requested for evidence. In the eyes of the Internal Revenue Service, a gift to a charity is not eligible for a tax deduction until title has passed to the charity (usually evidenced by a deed of gift or other donative evidence and evidence that the museum accepted the gift) and the donor has relinquished control over the object. Thus, evidence that the museum had a deed of gift in hand on December 31 and has accepted the gift does not secure a tax deduction for the donor for that year unless the museum can also verify that the donor effectively relinquished control of the gift before the end of the year.487 (And vice versa, if there is evidence that the gift was in hand on December 31, the museum can be asked to document that there was in fact a deed of gift and an acceptance in that year.) A museum should keep and, if necessary, disclose these records meticulously.488 Also, a museum should go through existing records in about October of each year, looking for incomplete gift transactions. Donors can then be put on notice that if a tax deduction is to be sought for that year, immediate action is necessary to complete Internal Revenue Service requirements.

The insistence on “donor relinquishment of control” as a requisite for a tax deduction stems from earlier abuses when donors gave paper evidence of gifts to charitable organizations but delayed delivery indefinitely in order to have continued enjoyment of the objects in question. In effect, these “donors” had the benefit of a charitable deduction on their income tax with no concurrent benefit to the public. To prevent the continuance of such abuses, the Internal Revenue Code was amended so that a charitable contribution deduction is not permitted for a “future interest” in personal property. “The term ‘future’ interest includes situations in which a donor purports to give tangible personal property to a charitable organization, but has an understanding, arrangement, agreement, etc., whether written or oral, with the charitable organization which has the effect of reserving to, or retaining in, such donor a right to the use, possession, or enjoyment of the property.”489 (There is one exception to this rule, a “fractional gift.” See Chapter XII, “Tax Considerations,” Section D, “Spreading Out Charitable Deductions.”)

Exactly when possession of a gift passes depends on when it is established that the donor relinquished control. In other words, “donor relinquishment of control” is the key issue. To date, some general observations can be offered on this question. Ordinarily, the mailing of a check or an endorsed stock certificate is deemed relinquishment of control if the check or certificate clears in due course. Stock certificates forwarded through the donor’s broker or the issuing corporation are not deemed “relinquished” until the stock is transferred on the books of the corporation.490 For museums, “donor relinquishment of control” is usually evidenced by the physical transfer of the object to the museum (or the museum’s agent) with “no strings attached.” This relatively simple test has been further refined by the following IRS rulings.

In Winokur v. Commissioner, a donor gave a museum a partial interest in a collection of art (a fractional gift).491 The museum had the right, therefore, to possess the collection for a certain period of the year that conformed to its fractional interest. The question posed was this: If the museum failed to take possession of the collection for the time allotted to it in a year, did this nullify the donor’s right to declare a fractional gift for the year? The court held that the right to current possession was real (i.e., the museum could have demanded possession), and this was all that was required to validate the fractional gift. In other words, the donor had in fact relinquished control over that fraction of the art collection. (This case was decided before the legislation creating the “fractional gift” option was amended. In another situation, “IRS Private Letter Ruling 9218067,”492 donors planned to execute a deed of gift transferring art objects to a museum that was then under construction. The museum was not expected to open for a year after the deed of gift was signed. It was anticipated that the donors would retain and display the art objects in their home until the museum opened. The question for the Internal Revenue Service was whether this arrangement invalidated a tax-deductible gift for the donors for the year in which they signed the deed of gift. The ruling of the Internal Revenue Service was that the understanding and expectation of the parties did not result in “a tacit reservation by the donors of a present right of possession.” Accordingly, the donors in this situation would, on the execution of the deed of gift, “relinquish control,” and the contribution of the art objects would qualify as a charitable contribution.

Even though the Internal Revenue Service has demonstrated a willingness to be somewhat flexible in interpreting “donor relinquishment of control,” museums evaluating similar situations should remember why this requirement was first inserted into the IRS Code. Museums should also remember this provision of the tax code, and its interpretation, when a donor requests to borrow back an object that has been donated.493

Intended Use of the Gift. As explained in this chapter’s Section A on the meaning of the word “accession,” and in Chapter XII, “Tax Considerations,” Section C, “Concept of ‘Unrelated Use,’ ” the Internal Revenue Code draws a distinction between gifts donated to a charity for the organization’s “related use” and those donated for an unrelated use. The former affords a donor more favorable tax advantages. If a gift or group of similar objects being donated is worth $5,000 or more, the donor is required to file an IRS Form 8283 to qualify for an income tax deduction. On the Form 8283, the museum is required to sign indicating receipt of the gift and in addition to designate whether the gift is being put to a “related use” or not. A museum’s acquisition procedures, therefore, should recognize this distinction. For example, raising money through the sale of objects is not considered a related use for a museum. Thus, if an object is being accepted by a museum so that it can be sold, the proposed use should be a matter of record and should be understood by the donor. The acknowledgment to the donor should be worded accordingly. Also, as previously explained, such an object is not “accessioned.” The museum’s goal should be to avoid even the appearance of collusion to circumvent tax code requirements.494

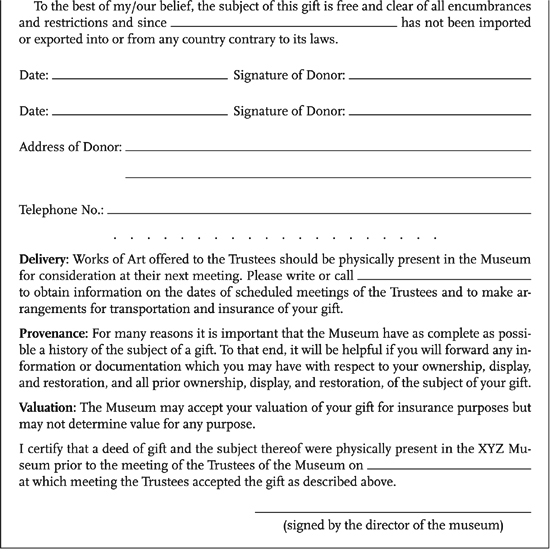

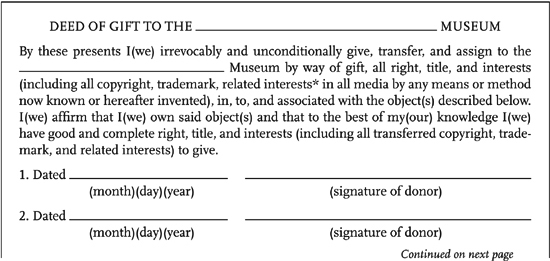

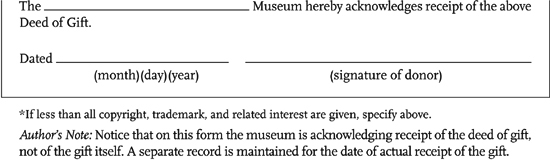

Figure IV.8

Deed of Gift Samples

SAMPLE I: DEED OF GIFT (DEVELOPED BY AN ART MUSEUM)

SAMPLE 2: DEED OF GIFT (DEVELOPED BY A HISTORY MUSEUM)

SAMPLE 3: DEED OF GIFT (FOR THE TRANSFER OF A VARIETY OF TYPES OF OBJECTS, ASKING FOR A NONEXCLUSIVE LICENSE, NOT FULL COPYRIGHT)

SAMPLE 4: NONEXCLUSIVE LICENSE DEVELOPED BY AN ART MUSEUM

Figure IV.9

Seller’s Warranty Samples

SAMPLE I: SAMPLE WARRANTY FROM ART VENDOR

SAMPLE 2: SAMPLE WARRANTY FROM ART VENDOR

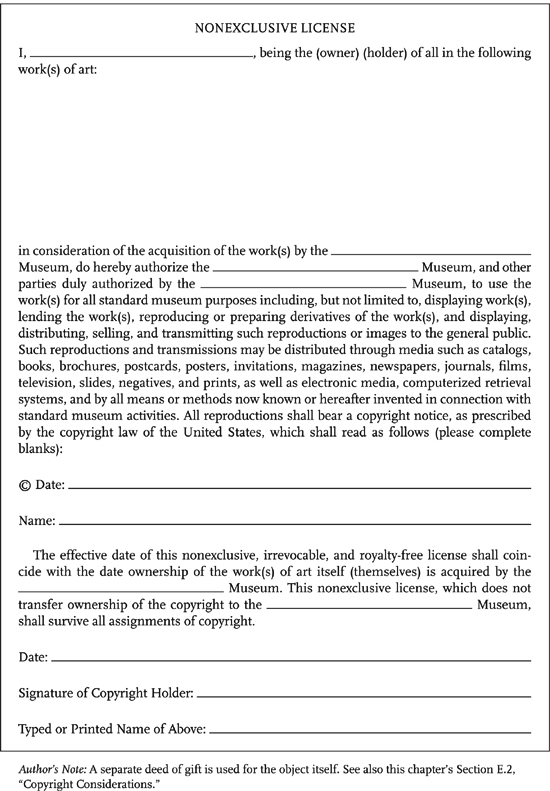

Figure IV.10

J. Paul Getty Museum Acquisition Policy (2006)

1. See also this chapter’s Section F, “Acquisition Procedures.”

2. This is not to imply that, once accessioned, an object can never be removed from the collection. (See Chapter V, “The Disposal of Objects: Deaccessioning.”) Experience and changing circumstances may justify removal. However, if a museum wants to maintain its integrity, each decision to accession should be made thoughtfully and in good faith. If accessioning is used merely to “cool” (i.e., hold for a discrete period) gifts before disposal, a serious lack of professional ethics is evident.

3. Such gifts of capital gain property may normally be deducted at their fair market value. See Chapter XII, “Tax Considerations.”

4. The fair market value of a gift of tangible personal property that is put to an unrelated use by the charitable organization must be reduced by 100 percent of its appreciation. (“Appreciation” is fair market value minus the donor’s basis in the property.) See IRS Publication 526, “Charitable Contributions,” for additional information. See also IRS Code § 170(e)(1)(B), IRS Regulations § 1.170A-4(b)(3), and Chapter XII, “Tax Considerations.”

5. The IRS takes the position that a gift of tangible personal property to a charitable organization may be treated as put to a related use if (1) the taxpayer establishes that the property is not in fact put to an unrelated use by the donee; or (2) at the time of the contribution or at the time the contribution is treated as made, it is reasonable to anticipate that the property will not be put to an unrelated use by the donee (see IRS Publication 526, “Charitable Contributions,” and IRS Regulation § 1.170A-4(b)(3)(ii). See also Chapter XII, “Tax Considerations,” noting especially Section C, “Concept of ‘Unrelated Use.’ ” Note also the discussion in Chapter V, “The Disposal of Objects: Deaccessioning,” Section B.2.e, “Notification to Donor of Deaccession,” which explains IRS notification requirements by the donee organization on related use when certain gifts are made and when these gifts are transferred by that donee organization within three years of receipt.

6. If a batch or lot accession has been determined to be appropriate, museum procedures regarding the deaccessioning of items within that batch or lot may be more relaxed. See Chapter V, “The Disposal of Objects: Deaccessioning,” Section B.2.b, “The Proper Authority to Approve a Decision to Deaccession.”

7. See Chapter VII, “Unclaimed Loans,” footnote 17, on the cost of maintaining collection objects.

8. A bequest is something left or given under a will, as distinct from a gift, which is given during the life of the donor.

9. It is important that the museum deal with the appropriate party representing an estate (the person appointed by the court to represent the estate or the attorney advising that person). If the museum is in doubt on this issue, it should seek legal advice. If the museum is approached by heirs of the deceased and the museum is offered property formerly belonging to the deceased “in memory of the deceased” (in other words, the property was not bequeathed to the museum in the will), this is not a bequest situation. It is a gift from the heirs. In such situations, the museum should seek legal advice if there is any question of the ability of the offering party to pass full and clear title.

10. There may be instances when circumstances show that the decedent left property to the museum either for accessioning or, in the discretion of the museum, for immediate sale to benefit the museum. In estate tax situations (as distinct from income tax situations), the “related use” question normally does not arise. The exception concerns certain situations involving copyright; see Internal Revenue Code (26 U.S.C.) § 2055(e) (4), Regulation (26 C.F.R.) § 20.2055–2(e)(11). But there can be public perception problems. Each such case should be carefully weighed so that the museum is satisfied that a decision to accept and sell is prudent in light of all other considerations.

11. See I. DeAngelis, “Wills and Estates Checklist for Museum Staff Administering Bequests,” and N. Ward, “Bequests: What Should a Museum Do to Protect Its Interests as Beneficiary under a Will?,” both in American Law Institute-American Bar Association (ALI-ABA), Course of Studies Materials: Legal Problems of Museum Administration (Philadelphia: ALI-ABA, 1994). See also B. Wolff, “Processing Bequests: From Notice of Probate to Receipt and Beyond,” in American Law Institute-American Bar Association (ALI-ABA), Course of Studies Materials: Legal Problems of Museum Administration (Philadelphia: ALI-ABA, 1996), for a detailed discussion of procedural matters.

12. The party having the burden of proof in a lawsuit must come forward with a preponderance of evidence in order to prevail. In other words, more in the way of convincing evidence is required of the one with the burden of proof.

13. In Christians v. Crystal Evangelical Free Church (In re Young), 82 F.3d 1407 (8th Cir. 1996), vacated, 521 U.S. 1114 (1997), reinstated, 141 F.3d 854 (8th Cir. 1998), cert denied, 525 U.S. 811 (1998), a church that was a charitable donee was able to retain a gift made by donors within one year of bankruptcy, but the decision rested on a federal statute (the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993) and, hence, may be of slight comfort to museums. In the case of City of Boerne v. Flores, decided by the U.S. Supreme Court on June 25, 1997, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act was declared unconstitutional, thus removing any special protection that religious organizations might have in later challenges of this nature. In the “New Era” scandal, a massive Pennsylvania-based scheme to fraudulently manipulate charitable donations, many charities that unwittingly became involved were, as of early 1997, voluntarily returning portions of donations they received in order to relieve losses suffered by other charities. See “New Era Philanthropy Settlement Could Recoup Money for Charities,” Chronicle of Philanthropy, 46 (Sept. 5, 1996). Note also the comments in this chapter’s Section A, “The Meaning of the Word ‘Accession,’ ” regarding the uncertainty of bequests until all estate affairs have been settled.

14. Black’s Law Dictionary (6th ed., 1990). A plaintiff in such an action must also show that he or she suffered damages as a result of the alleged misrepresentation.

15. A tort is a legal wrong committed against the person or the property of another independent of contract.

16. The Uniform Commercial Code (U.C.C.) governs the sale of personal property. The code has been adopted, with occasional modification, by all states except Louisiana and by the District of Columbia. In addition, some states have legislation that specifically addresses the sale of art or unique objects.

17. D. Frisch, “David Frisch on Warranty of Title under U.C.C. Section 2-312,” 2008 Emerging Issues 3199, LexisNexis Emerging Issue Analysis (Dec. 2008). See 2003 Official Comment on Amendments to Uniform Commercial Code by the American Law Institute and National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws, “U.C.S. § 2-312: Section 2-312 Warranty of Title and Against Infringement: Buyer’s Obligation Against Infringement.” F. Feldman and S. Weil, Art Law (Boston: Little Brown, 1986, supp. 1993), Chapters 9 and 10, is an excellent resource on the law regarding private and public sales. Also, “Stolen Art Sold at Auction,” 5 Stolen Art Alert 4 (June 1984), is a series of letters written to a London magazine on the subject of stolen art sold at auction. The letters illustrate the complex issues that can arise and the differing opinions as to how such situations should be handled. In the case of Autocephalous Greek-Orthodox Church v. Goldberg and Feldman Fine Arts, Inc., 717 F. Supp. 1374 (S.D. Ind. 1989), aff’d, 917 F.2d 278 (7th Cir. 1990), the court discusses the following question: When can an art dealer qualify as a good-faith purchaser of art?

18. 267 N.Y.S.2d 804, 49 Misc. 2d 300 (1966), modified 28 A.D. 2d 516, 279 N.Y.S.2d 608 (1967), third party claim rev’d on other grounds, 24 N.Y.S.2d 91, 298 N.Y.S.2d 979, 246 N.E.2d 742 (1969).

19. 541 F. Supp. 80, rev’d and remanded for new trial, 693 F.2d 259 (2d Cir. 1982). This case eventually became moot when Italy decided it would not question the sale.

20. 891 F. Supp. 1361 (N.D. Cal. 1995). See also Cantor v. Anderson, 639 F. Supp. 364 (S.D.N.Y. 1986); and Porter v. Wertz, 416 N.Y.S.2d 254 (N.Y. App. Div. 1979), aff’d, 439 N.Y.S.2d 105 (N.Y. 1981).

21. The express warranties need not be recited in the sales contract itself. See Comment 7 on § 2–313 of the U.C.C.

22. See discussion of fact versus opinion in Chapter XIII, “Appraisals and Authentications.”

23. In Weisz v. Parke-Bernet Galleries, Inc., 67 Misc. 2d 1077, 325 N.Y.S.2d 576 (1971), rev’d, 77 Misc. 2d 80, 351 N.Y.S.2d 911 (1974), a case decided under a statute similar to the U.C.C., the plaintiff failed to prevail in a suit to recover for the purchase of fake art. But see Legum v. Harris Auction Galleries, File No. 81–013 (Md. Consumer Protection Div., Office of the Att. Gen., Apr. 1983). Here the seller was afforded some relief under the Maryland Consumer Protection Law. Since the Weisz case, mentioned above, New York has enacted legislation that specifically addresses warranties in the sale of fine art when the seller is an “art merchant” and the buyer is a nonmerchant.

24. On the general issue of the application of the U.C.C. to the sale of art, see Note, “Uniform Commercial Code Warranty Solutions to Art Fraud and Forgery,” 14 Wm. and Mary L. Rev. 409 (1972); and F. Feldman and S. Weil, Art Law (Boston: Little Brown, 1986, supp. 1993). If a cause of action can be maintained under the U.C.C., relief may prove generous. Section 2–714(2) of the code states the following: “The measure of damages for breach of warranty is the difference at the time and place of acceptance between the value of the goods accepted and the value they would have had as warranted, unless special circumstances show proximate damages of a different amount.” Consider the following example. A painting is purchased for $1,000, and a number of years later the purchaser discovers that title is faulty. The painting is now worth $5,000, and the seller is sued successfully under the U.C.C. The plaintiff may be able to recover not merely the $1,000 purchase price but $5,000, the present fair market value. (See Menzel v. List discussed in this chapter’s Section D.5, “Stolen Property,” regarding the recovery of List against the Perls.)

25. See, for instance, Firestone & Parson, Inc. v. Union League of Philadelphia, 672 F. Supp. 819 (E.D. Pa. 1987); and Wilson v. Hammer Holdings, Inc., 850 F.2d 3 (1st Cir. 1988). Both are reproduced in F. Feldman and S. Weil, Art Law (Boston: Little Brown, 1986, supp. 1993).

26. “Fine art” is defined to mean a painting, sculpture, drawing, or work of graphic art.

27. New York Arts and Cultural Affairs Law, Art. 13. See, for instance, Dawson v. G. Maliney, Inc., 463 F. Supp. 461 (1978); and Pritzker v. Krishna Gallery of Asian Arts, 93 C 4147. The latter, a case decided by a federal judge in Chicago on May 7, 1997, raised the issue of whether one knowledgeable in the arts can seek the protection of the New York statute.

28. Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. §§ 442.321 et seq.

29. The following states have legislation governing the sale of fine prints: Arkansas, California, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Oregon, South Carolina, and Wisconsin.

30. New York Arts and Cultural Affairs Law, Art. 15.

31. Ibid., Art. 14.

32. See, for example, New York City Consumer Protection Law, Reg. 30.

33. Legum v. Harris Auction Galleries, File No. 81-013 (Md. Consumer Protection Div., Office of the Att. Gen., Apr. 1983).

34. 15 U.S.C. §§ 41 et seq.

35. 15 U.S.C. §§ 2101–6.

36. 18 U.S.C. §§ 1341–43.

37. W. Prosser, Handbook of the Law of Torts (Hornbook Series), 4th ed. (St. Paul, Minn.: West Pub. Co., 1971). For a general discussion on the problem of fake art, see S. Hodes, “ ‘Fake’ Art and the Law,” 27 Fed. B.J. 73 (Winter 1967). See also Committee on Art of the Bar of the City of New York, “Legal Problems in Art Authentication,” 21 Records of N.Y.C.B.A. 96–102 (1966); and F. Feldman and S. Weil, Art Law (Boston: Little Brown, 1986, supp. 1993). For problems in the print market, see S. Hobart, “A Giant Step Forward: New York Legislation on Sales of Fine Art Multiples,” 7 Art and the Law 261 (1983). For an article on how a museum reacts when it suspects that one of its works is a fake, see R. Flamini, “Not the Real Thing,” 32 Washingtonian (No. 2, Nov. 1996).

38. If purchased property turns out to be stolen and has to be returned, the museum purchaser might have a cause of action against the seller based on the sales contract or some form of misrepresentation (see previous sections of this chapter).

39. Wood v. Carpenter, 101 U.S. 135, 25 L.Ed. 807 (1879).

40. “Conversion” is a civil action for money damages based on the unlawful withholding of property. If the plaintiff seeks the return of the property itself, rather than its value, the action may be called “replevin.”

41. In State of North Carolina v. West, 293 N.C. 18, 235 S.E.2d 150 (1977), North Carolina was demanding the return of certain historic documents that were once the property of the state. The court held that in North Carolina the statute of limitations would not be applied against the state. Individual state law should be checked on this point.

42. This interpretation is frequently referred to as the “discovery rule.” See 51 Am. Jur. 2d, “Limitation of Actions,” § 146, at 716. See also Comment, “The Recovery of Stolen Art: Of Paintings, Statues, and Statutes of Limitations,” 27 U.C.L.A. L. Rev. 1122 (1980). California decided to settle this matter in a law specifically addressing claims against museums for works of art. Cal. Code Civ. Proc. § 338(c) (3) (2011) reads in pertinent part as follows: “[A]n action for the specific recovery of a work of fine art brought against a museum, gallery, auctioneer, or dealer, in the case of an unlawful taking or theft, as described in Section 484 of the Penal Code, of a work of fine art, including a taking or theft by means of fraud or duress, shall be commenced within six years of the actual discovery by the claimant or his or her agent, of both of the following: (i) The identity and the whereabouts of the work of fine art. In the case where there is a possibility of misidentification of the object of fine art in question, the identity can be satisfied by the identification of facts sufficient to determine that the work of fine art is likely to be the work of fine art that was unlawfully taken or stolen. (ii) Information or facts that are sufficient to indicate that the claimant has a claim for a possessory interest in the work of fine art that was unlawfully taken or stolen. (B) The provisions of this paragraph shall apply to all pending and future actions commenced on or before December 31, 2017, including any actions dismissed based on the expiration of statutes of limitation in effect prior to the date of enactment of this statute if the judgment in that action is not yet final or if the time for filing an appeal from a decision on that action has not expired, provided that the action concerns a work of fine art that was taken within 100 years prior to the date of enactment of this statute.”

An earlier version of this law that referred only to Nazi-era art was declared unconstitutional, leading the California legislature in 2010 to broaden the application of this provision to fine arts generally. See the discussion in this chapter’s footnote 166.

43. 267 N.Y.S. 2d 804, 49 Misc. 2d 300 (1966), modified 28 A.D. 2d 516 (1967), 279 N.Y.S. 2d 608; third party case rev’d on other grounds, 24 N.Y. 2d 91, 298 N.Y.S. 2d 979, 246 N.E. 2d 742 (1969).

44. 170 N.J. Super. 75, 405 A.2d 840, 416 A. 2d 862 (1980). See also P. Amram, “The Georgia O’Keeffe Case: New Questions about Stolen Art,” Museum News 49 (Jan.–Feb. 1979); and P. Amram, “The Georgia O’Keeffe Case: Act II,” Museum News 47 (Sept.–Oct. 1979).

45. 24 N.Y. 2d 91 (1969).

46. “Replevin” is an action seeking the return of misappropriated property.

47. Note the previous section on warranties in a sale.

48. The trial court opinion is cited as O’Keeffe v. Snyder, Docket No. L-27517-75 (N.J. Super. Ct., Law Div., Mercer County, July 1978). It is printed in Museum News 50 (Jan.–Feb. 1979).

49. 170 N.J. Super. 75, 405 A. 2d 840 (App. Div. 1979), 848.

50. 83 N.J. 478, 416 A. 2d 862 (1980), 869.

51. O’Keeffe elected not to pursue the case further, and the parties entered into a private settlement.

52. 170 N.J. Super. 75, 416 A. 2d 862 (App. Div. 1979), 870.

53. 170 N.J. Super. 75, 416 A. 2d 862 (App. Div. 1979), 874. See also Desiderio v. D’Ambrosio, 190 N.J. Super. 424, 463 A. 2d 986 (Ch. Div. 1983).

54. 536 F. Supp. 829 (E.D.N.Y. 1981), aff’d, 678 F.2d 1150 (2d Cir. 1982). See also F. Feldman, “The Title to a Work of Art Means Much More Than Just Its Name,” Collector-Investor 38 (Feb. 1982).

55. 658 F. Supp. 688 (S.D.N.Y. 1987), rev’d, 836 F.2d 103 (2d Cir. 1987).

56. Both DeWeerth and Elicofon were tried in federal court. Federal courts, as appropriate, apply the law of the state that is controlling. If the law of the state is unclear, the federal court “makes an estimate of what the state’s highest court would rule to be its law.” The federal court sitting in New York also has the option to submit the unresolved state law issue to the New York Court of Appeals (in other words, it can defer to a New York court to bear the burden of interpreting a questionable issue of state law). That option was not elected in DeWeerth—a case in which the interpretation of the law would alter the outcome—but in its opinion the court does discuss why it decided not to seek state court clarification of the law.

57. After the decision in the later-decided Guggenheim case, which is discussed next, DeWeerth went back to federal court to request a rehearing of her case. The request was granted, and she prevailed: 804 F. Supp. 539 (D.N.Y. 1992). Baldinger then appealed this decision, and she prevailed on a procedural issue. The court held, in effect, that the Guggenheim decision amounted to a change in New York law and that subsequent change in state law is not grounds to reopen a federal diversity case decided under prior law of the state. 28 F. R. Serv. 3d 1231 (2d Cir. 1994), cert. denied, 130 L.Ed. 2d 419, 115 S. Ct. 512 (1994).

58. Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation v. Lubell, 77 N.Y. 2d 311, 567 N.Y.S. 2d 623, 569 N.E. 2d 426 (N.Y. Ct. App. 1991). A somewhat similar case was initiated by a museum against a college. In this case, an artifact mysteriously disappeared from the college’s collection (a suspected case of employee theft), and the artifact later surfaced in a museum collection. The college had not pursued its loss, but when it eventually learned of the whereabouts of the object, it demanded a return. The museum refused based on the theory that rewarding the college for its negligence would be unjust. Subsequently, the museum sued “to quiet title”—to seek court confirmation of its title. The case was settled out of court. Museum of Fine Arts v. Lafayette College, C.A. #91-10922MA (U.S.D.C., D. Mass. Filed Mar. 27, 1991). In 1990, the Art Institute of Chicago announced that it was officially listing as “lost” one of Georgia O’Keeffe’s works that had been missing for twenty years. The loss was confirmed after a major inventory. The Art Institute then (in 1990) notified law enforcement officials and art-loss registers of the loss. See Chicago Tribune, Aug. 14, 1990, 1.

59. See “Suit over Chagall Watercolor Is Settled Day after Trial Starts,” New York Times, Dec. 29, 1993. A subsequent case that concerns lost art is Hoelzer v. Stamford, 933 F.2d 1131 and 972 F.2d 495 (2d Cir. 1991), cert. denied, 506 U.S. 1035, 121 L.Ed. 2d 687 (1992). Hoelzer is a very convoluted case that involves not theft but a series of highly questionable acts by city and federal employees. See also The Republic of Turkey v. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 762 F. Supp. 44 (S.D.N.Y. 1990), in which the Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City sought to have Turkey’s claim for return of antiquities dismissed as time barred under a statute of limitations. The court refused to dismiss and, relying on the Guggenheim reasoning, held that the case would have to be heard on its merits with a weighing of the equities under a “laches” defense. Another case of considerable interest is Autocephalous Greek-Orthodox Church v. Goldberg and Feldman Fine Arts, Inc., 717 F. Supp. 1374 (S.D. Ind. 1989), aff’d, 917 F.2d 278 (7th Cir. 1990). Here, Cyprus was seeking the return of four Byzantine mosaics looted from a church in Cyprus in the late 1970s and purchased in Europe by an American dealer many years later. The decision discusses such questions as the following: The law of which country applies? When did the statute of limitations begin? When can a dealer qualify as a “good-faith” purchaser?

60. When a statute of limitations defense is raised, this matter is examined first by the court before a full trial is conducted. If the court finds, on the evidence presented, that the statute has in fact run, the case is dismissed at that point. In other words, the rest of the case is barred from court. Although a full trial is often required for a laches defense, a New York court dismissed a case without a trial on summary judgment based on a laches defense in a case where delay by plaintiffs to bring suit was so egregious as to require dismissal. Wertheimer v. Cirker’s Hayes Storage Warehouse, Inc., No. 105575/00, slip op. (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Sept. 28, 2001), aff’d, 300 A.D.2d 117 (N.Y. App. Div. 2002).

61. Not long before the Guggenheim case was decided, there had been a series of efforts in New York to pass legislation that would limit the time during which one could question the title of cultural and scientific objects purchased in good faith by nonprofit organizations. In 1985, one of these bills (S. 3273, “An Act to Amend the General Business Law, in Relation to Actions Against Non-Profit Organizations for Recovery of Objects”) actually passed the legislature but was vetoed by the governor because of the fear, expressed by many, that the bill would make New York a haven for art of questionable provenance. In the same year, two similar bills were introduced to the U.S. Congress (S. 605 and S. 1523). Neither bill was favorably acted on when few came forward to endorse either one.

62. See, for example, Autocephalous Greek-Orthodox Church v. Goldberg and Feldman Fine Arts, Inc., 717 F. Supp. 1374 (S.D. Ind. 1989), aff’d, 917 F.2d 278 (7th Cir. 1990); and Eristoy v. Rizek, CA #93-6215, U.S.D.C. (E.D. Pa.), Feb. 23, 1995. In the latter stolen art case, the court, citing O’Keeffe, “balanced the equities” as the proper exercise of the discovery rule. Several articles discuss some of these cases: I. DeAngelis, “Civil Claims for Recovery of Stolen Property: Developments in the Law and Lessons for Museums,” in American Law Institute–American Bar Association (ALI-ABA), Course of Studies Materials: Legal Problems of Museum Administration (Philadelphia: ALI-ABA, 1992); P. Gerstenblith, “Guggenheim and Lubell,” I International Journal of Cultural Property (No. 1, 1992); S. Bibas, “Note: The Case against Statutes of Limitations for Stolen Art,” 103 Yale L.J. 2437 (1994).

63. See Chapter V, “The Disposal of Objects: Deaccessioning.”

64. See Chapter XIV, “Care of Collections,” Section B, “Inventory Procedures and the Reporting of Missing Objects,” for more discussion on this topic.

65. 54 C.J.S., “Limitations of Actions,” § 119, at 23 (1948).

66. Refer to this chapter’s footnote 44 and the last decision, 416 A.2d 862. In this regard, the O’Keeffe court overruled Redmond v. New Jersey Historical Soc., 132 N.J. Eq. 464, 28 A. 2d 189 (1942), a case involving a museum’s refusal to return a painting, which had been placed on loan subject to the occurrence of certain events.

67. But see Wogan v. State of Louisiana, No. 81-2295 (La. Civ. Dist. Ct. for Parish of Orleans, Jan. 8, 1982). Wogan involved a demand for the return of a painting originally placed on loan in a museum and subsequently claimed by the museum as its own. Citing the peculiarities of Louisiana law, the court would not recognize an adverse possession defense. See also discussions in Chapter VII, “Unclaimed Loans,” and Chapter X, “Objects Found in the Collections.”

68. See Chapter IV, “The Acquisition of Objects: Accessioning,” Section D.6, “Objects Improperly Removed from Their Countries of Origin.”

69. Section 312 of Pub. L. 97–446. Property imported for temporary exhibit and protected by a declaration of immunity from seizure under 25 U.S.C. § 2549 is also exempt.

70. The term “provenance” refers to information on the history of an object. This includes its creation, the trail of ownership, exhibition, and publication. “Provenience” is a term used to define a work’s archaeological find spot. An object’s provenience is a part of its provenance. S. Urice, “Antiquities as Cultural Property: Dealing with the Past, Looking to the Future—An Introduction,” in American Law Institute–American Bar Association (ALI-ABA), Course of Studies Materials: Legal Issues in Museum Administration (Philadelphia: ALI-ABA, 2007), 26, 25, n2. “Unprovenanced” objects are those that come with no information about their history. A complete provenance would show an unbroken link from the time it was created (or discovered) until today. Rarely do any objects have such complete histories. The only exceptions are objects scientifically excavated, documented, and then published. Incomplete or partial provenance refers to objects with some history of ownership, while objects with no provenance refers to those that are on the art market in the hands of a dealer or auction house with no other information as to their origin. S. Urice, “Between Rocks and Hard Places: Unprovenanced Antiquities and the National Stolen Property Act,” 40 New Mex. L. Rev. 123, 125 (2010).

71. Undocumented property claims can also be national rather than international in nature. For example, a clandestine removal of archaeological material from federal or Native American lands in this country would give rise to a claim on the part of the U.S. government or the appropriate tribe, and it would present many of the difficulties of proof inherent in an “undocumented property” claim brought in a U.S. court by a foreign country.

72. “Art rich” nations are also called “source nations,” and “art poor” nations are also called “market nations.” The term “cultural properties” is generally defined to mean properties that, on religious or secular grounds, are designated by a nation as being of unique importance to the nation for reasons relating to archaeology, prehistory, history, literature, art, or science. As highlighted by the implementation of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (1990), the use of the term “cultural property” to include human remains is offensive to many. See also J. Merryman, “The Public Interest in Cultural Property,” 77 Calif. L. Rev. 339 (1989), reprinted in J. Merryman, Thinking about the Elgin Marbles: Critical Essays on Cultural Property, Art and Law, 2d ed. (London: Kluwer Law International, June 2009). At its twentieth session in 1978, the General Conference of UNESCO defined it as follows: “ ‘cultural property’ shall be taken to denote historical and ethnographic objects and documents including manuscripts, works of the plastic and decorative arts, paleontological and archeological objects, and zoological, botanical, and mineralogical specimens” (Article 3, para. 1), accessed May 6, 2011, http://unesdoc.unesco.org/Images/0014/001459/145960e.pdf.

73. This is a very general statement. The extent of these “unique claims” and how such determinations are made continue to be debated. For differing viewpoints, see J. Cuno, Who Owns Antiquity? Museums and the Battle over Our Ancient Heritage (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton U. Press, 2008); K. Gibbon, ed., Who Owns the Past? Cultural Policy, Cultural Property, and the Law (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers U. Press, 2005); P. Messenger, The Ethics of Collecting Cultural Property: Whose Ethics? Whose Property? (Albuquerque: U. of New Mexico Press, 1989); J. Merryman, “The Nation and the Object,” 3 International Journal of Cultural Property (1994); J. Greenfield, The Return of Cultural Treasurers (New York: Cambridge U. Press, 1989); and E. Green, ed., Ethics and Values in Archeology (New York: Free Press, 1984).

74. P. Sheets, “The Pillage of Prehistory,” 38 Am. Antiquity 317, 319 (1973). See also C. Coggins, “Archeology and the Art Market,” 175 Science 263 (1972); M. Robertson, “Monument Thievery in Mesoamerica,” 37 Am. Antiquity 147 (1972); “International Protection of Cultural Property,” 1 Art Research News (No. 2, 1981); O. Acar and M. Kaylan, “The Hoard of the Century,” Connoisseur 74 (July 1988); G. Chippendale et al., “Collecting the Classical World: First Steps in a Quantitative History,” 10 Int’l J. of Cultural Prop. 1 (2001); M. Braden, “Trafficking in Treasures,” 3 American Archaeology 19 (No. 4, Winter 1999–2000); R. Atwood, “Guardians of the Dead,” 56 Archeology (No. 1, Jan./Feb. 2003); M. Braden, “Trafficking in Treasures,” 3 American Archaeology 19 (No. 4, Winter 1999–2000).

75. C. Coggins, “Illicit Traffic of Pre-Columbian Antiquities,” 29 Art J. 94 (1969).

76. S. Urice, “Antiquities as Cultural Property: Dealing with the Past, Looking to the Future, An Introduction,” in American Law Institute–American Bar Association (ALI-ABA), Course of Studies Materials: Legal Issues in Museum Administration (Philadelphia; ALI-ABA 2007), 23, 29; P. Bator, “An Essay on the International Trade in Art,” 34 Stan. L. Rev. 275 (1982). This article was also published in book form: P. Bator, The International Trade in Art (Chicago: U. of Chicago Press, 1983), 9–13.

77. INTERPOL (International Criminal Police Organization) is a voluntary organization that promotes and organizes collaboration among national law enforcement agencies. The General Secretariat of INTERPOL is located in Lyons, France. INTERPOL has a network of some 170 member countries, and one of its most important roles is to act as a clearinghouse for information on offenses considered to be of international interest (accessed May 9, 2011, http://www.interpol.int).

78. INTERPOL provides a system for circulating information in the form of a database accessible to member countries as well as in CD-ROM form (accessed May 9, 2011, http://www.interpol.int/Public/WorkOfArt/Default.asp). Key to recovery is an efficient and standard international documentation system. See R. Thornes, Protecting Cultural Objects through International Documentation Standards: A Preliminary Survey (Malibu, Calif.: Getty Art History Information Program, 1995), 7. Object ID, an international standard was initiated by the J. Paul Getty Trust and has been maintained since 2004 by the International Council of Museums (ICOM) (accessed May 9, 2011, http://archives.icom.museum/object-id/). ICOM is a nongovernmental organization composed of museums and representatives of museums. It was established in 1946 and has its headquarters in Paris. For ICOM’s early role in working for international restraints on the illicit international movement of cultural property, see J. Nafziger, “Regulation by the International Council of Museums: An Example of the Role of Non-Governmental Organizations in the Transnational Legal Process,” 2 Denver J. of Int’l L. and Pol’y 231 (1972). See also S. Ciccotti, “ICOM Celebrates 50 Years of Global Activism,” Museum News 28 (Nov.–Dec. 1996).

79. M. Howe, “Turkey Demands Return of Stolen Art,” New York Times, Feb. 23, 1981, A.3, Col. 1. Copyright © 1981 by the New York Times Co. Reprinted by permission.

80. Stolen Art Alert 1 (July 1982).

81. Historically, the U.S. government has viewed Native American tribes as foreign nations, as evidenced by its negotiation of treaties with individual tribes. To this day, Native American tribes are reserved certain rights of self-government. The issue of Native American repatriation claims is discussed more fully in this chapter’s Section D.6.i, “Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.”

82. See “Repatriation and the Law,” in M. Malaro, Museum Governance: Mission, Ethics, Policy (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994).

83. A copy of the text of the convention may be found on the UNESCO website; accessed May 9, 2011, http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=13039&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html.

84. For a brief account of the history of the convention and reactions to it, see A. Zelle, “Acquisitions: Saving Whose Heritage?,” Museum News 19 (Apr. 1971). See also ICOM News for Sept. 1969 and for Mar., June, and Sept. 1970. The most comprehensive study of the history of the UNESCO Convention is found in P. Bator,

“An Essay on the International Trade in Art,” 34 Stan. L. Rev. 275 (1982). This article was also published in book form: P. Bator, The International Trade in Art (Chicago: U. of Chicago Press, 1983). The UNESCO Convention does not address the subject of protecting underwater cultural heritage, which is subject to a separate 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Underwater Heritage, which is available online; accessed May 9, 2011, http://portal.unesco.org/culture/en/ev.php-URL_ID=34114&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html.

In addition to pursuing an international solution, the increased publicity given to the illicit traffic in pre-Columbian artifacts in the 1960s caused the United States to take two significant steps. The first was to enter into the bilateral Treaty of Cooperation between the United States of America and the United Mexican States Providing for the Recovery and Return of Stolen Archeological, Historical, and Cultural Properties, which was signed on July 17, 1970 (22 U.S.T. 494), in which the United States and Mexico agreed to cooperate in the recovery and return of certain cultural properties. In October 1972, Congress passed Pub. L. 92–587 (86 Stat. 1297), which regulates the importation of monumental-type pre-Columbian artifacts.

The treaty concerns itself with the recovery and return of “archeological, historical, and cultural properties” that belong to either country.

Under the treaty, both countries undertake to encourage the proper excavation and study of archaeological sites, to deter illicit excavations and the theft of properties covered by the treaty, to encourage the exhibit in both countries of properties covered by the treaty, and to permit legitimate international commerce in art objects. Also, each country agrees to assist in the return from its territory of stolen property covered by the treaty, and if the requesting party cannot otherwise effect recovery, the attorney general of the country where the property is located is authorized to institute civil proceedings on behalf of the requesting party. Expenses incident to a return are borne by the requesting party. Apparently, the first time Mexico asked for the assistance of the U.S. attorney general in this regard was in July 1978. At issue were pre-Columbian murals bequeathed to the de Young Museum in San Francisco. See B. Braun, “Subtle Diplomacy Solves a Custody Case,” Art News 100 (Summer 1982).

The second step to curtail the import of looted pre-Columbian material was to pass a law, Regulating the Importation of Pre-Columbian Monumental or Architectural Sculpture or Murals, Pub. L. 92–587, enacted in October 1972 (19 U.S.C. §§ 2091 et seq.). This law establishes a method of halting the importation into the United States of certain monumental-type pre-Columbian artifacts. The statute empowered the secretary of the treasury to promulgate a current list of stone carvings and wall artworks that are pre-Columbian monumental or architectural sculpture or murals; objects covered in the list cannot be imported into the United States without proof of a valid export permit from the country of origin. The statute is enforced at U.S. borders by U.S. Customs agents, and contraband objects are subject to forfeiture.

Articles forfeited to the United States are first offered for return to the country of origin, but the country of origin must bear all expenses incident to the return.

85. Statement by Mark B. Feldman, then assistant legal advisor for Inter-American affairs, Department of State, before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations.

86. An excellent overview of the divergent views expressed can be found in the legislative histories of the bills proposed to implement the convention: H.R. 5643 of the 95th Cong., H.R. 3403 of the 96th Cong., S. 1723 of the 97th Cong., 1st sess., and H.R. 4566 of the 97th Cong., 2d sess., the bill that eventually became law. See also L. DuBoff et al., “Proceedings of the Panel on the U.S. Enabling Legislation of the UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export, and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property,” 4 Syracuse J. Int’l L. & Com. 97 (1976); and M. Wisner, “Implementing the Convention on Illicit Traffic in Antiquities: Proposals, Past, and Prospective,” 2 Art Research News 3 (No. 1, 1983). The definitive work, as noted in this chapter’s footnote 82, is P. Bator, “An Essay on the International Trade in Art,” 34 Stan. L. Rev. 275 (1982). This article was also published in book form: P. Bator, The International Trade in Art (Chicago: U. of Chicago Press, 1983).

87. The values expressed in the debate by the collecting community versus the countries of origin (shared in part by the archaeological community) have been summarized as follows:

Collecting community: emphasis on humanity’s common interest in the past; favoring a free market in antiquities to make such a past widely available to museums and the public; the object does not necessarily belong to the current political state where it was discovered; art as ambassador should be free to travel across borders; source nation embargoes are the cause for the black market; objects without provenance still provide aesthetic and other educational value.

Countries of origin joined in some respects by the archaeological community: emphasis on a connection between cultural objects and national identity; any object found within a nation’s borders naturally belongs to the people of that nation; importance of preserving archaeological sites until they can be scientifically excavated as the only way to preserve their scientific and historical value; belief that the art market fuels looting and pillage.

See S. Urice, “Antiquities as Cultural Property: Dealing with the Past, Looking to the Future—An Introduction,” in American Law Institute–American Bar Association (ALI-ABA), Course of Studies Materials: Legal Issues in Museum Administration (Philadelphia: ALI-ABA, 2007), 23, 25, n.4. Compare the Brief submitted by the American Association of Museums, et al., as a friend of the court, with the Memorandum of Law submitted by the Archaeological Institute of America, et al., in the appeal of the so-called Steinhardt case: United States v. An Antique Platter of Gold, 184 F.3d 131 (2d Cir. 1999).

88. Title II of Pub. L. 97–446 is available online at the U.S. Department of State website on its Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs’ Cultural Heritage Center’s International Cultural Property Protection page; accessed May 9, 2011, http://exchanges.state.gov/heritage/index.html. Interestingly, in Sept. 1977, Canada adopted a Cultural Property Export and Import Act (Chapter 50.23–24, Elizabeth II, Vol. 1, No. 9, Canada Gazette, Part III), a portion of which is designed to implement the UNESCO Convention. The Canadian act provides a relatively simple format whereby the attorney general of Canada is charged with instituting the legal proceedings necessary to resolve claims of countries of origin. For a discussion of the Canadian act, see I. Clark, “The Cultural Property Export and Import Act: Legislation to Encourage Co-operation,” 2 Art Research News 8 (No. 1, 1983). One of the first cases arising under the act attracted international interest. In 1981, the New York art dealer Ben Heller brought into Canada for authentication by the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, and for possible sale, a Nigerian Nok sculpture. While in Canada, Heller and the owner of the sculpture, a Mr. Zango, were arrested by the Canadian government when they could not produce a Nigerian export license. A major issue in the case was what “illegal export” means under the Canadian statute. Does this phrase mean illegal export from the country of origin only after the effective date of the Canadian statute (1977) and/or Canada’s acceding to the UNESCO Convention (1978), or does it mean illegal export at any time, even years before these dates? See Between Her Majesty the Queen and Heller, Zango, and Kassam, In the Court of Queen’s Bench of Alberta, Judicial District of Calgary (Canada), as reported in Stolen Art Alert (Jan.–Feb. 1982) and (Oct. 1983). For another point of view on the Nigerian Nok case, see E. Eyo, “Repatriation of Cultural Heritage: The African Experience,” in F. Kaplan, ed., Museums and the Making of “Ourselves” (London: Leicester U. Press, 1994), 339–40.

89. See Chapter VIII, “International Loans,” for a description of this statute and current legal problems with its implementation

90. The authority for carrying out provisions of the CCPIA was transferred from the U.S. Information Agency (USIA) in 1998 to the secretary of state by the Foreign Affairs Reform and Restructuring Act, 22 U.S.C. 5401, et seq.

91. The U.S. Department of State website on its Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs’ Cultural Heritage Center’s International Cultural Property Protection page includes copies of the 1970 Convention and the CCPIA and CCPIA-based import restrictions, and the Cultural Property Advisory Committee page includes descriptions of membership and activities as well as a current list of convention signatories. The database of current import restrictions includes sample images of categories of import-restricted objects; http://exchanges.state.org.gov/heritage/culprop.html.

92. Accessed May 9, 2011, http://exchanges.state.gov/heritage/index.html.

93. See the list of signatories to the 1970 UNESCO Convention and the dates on which they signed on the Department of State website for cultural property; accessed May 30, 2011, http://exchanges.state.gov/heritage/culprop/background.html.

94. For the text of the convention, see the UNIDROIT website at http://www.unidroit.org. For the early history of UNIDROIT involvement, see the explanatory report that accompanies The International Protection of Cultural Property, a preliminary report issued by UNIDROIT in Aug. 1990. See also B. Hoffman, “How UNIDROIT Protects Cultural Property,” N.Y.L.J. (Mar. 3, 10, 1995); C. Lowenthal, “Stolen Art: A Positive Move toward International Harmony,” Museum News 22 (No. 5, Sept.–Oct. 1991); and L. Prott, “UNIDROIT Draft Convention Focuses on Purchasers,” Museum 221 (Vol. XLIII, No. 4, 1991).

95. One such case involving a documented object was Autocephalous Greek-Orthodox Church of Cyprus v. Goldberg & Feldman Fine Arts, Inc., 717 F. Supp 1374 (S.D. Ind. 1989), aff’d, 917 F. 2d 278 (7th Cir. 1990), in which mosaics that had been photographed on the walls of a church in Cyprus and published in an international publication in 1977 were apparently chipped away by looters and discovered in the hands of an art dealer in 1988.

96. McClain I, 545 F.2d 988 (5th Cir. 1977); McClain II, 593 F.2d 658 (5th Cir. 1979), cert. denied, 444 U.S. 918.

97. 720 F. Supp. 810 (C.D. Cal. 1989).

98. United States v. Schultz, 178 F. Supp 2d 445 (S.D. N.Y. 2002), aff’d 333 F3d 393 (2d Cir. 2003), cert. denied 157 L.Ed. 2d 891 (U.S. 2004).

99. An example of such an international agreement is the Treaty of Cooperation between the United States of America and the United Mexican States Providing for the Recovery and Return of Stolen Archeological, Historical, and Cultural Properties, 22 U.S.T. 494. The treaty, which is discussed in this chapter’s footnote 84, provides for the return, through diplomatic channels, of stolen archaeological, historical, and cultural objects that belong to the government. In United States v. McClain, this treaty was not invoked by Mexico, possibly because the treaty applies to objects of outstanding importance to the national patrimony and the objects at issue in McClain were not of this stature. Instead, criminal charges for theft were filed against the defendants by U.S. federal law enforcement officials.

100. J. Story, Commentaries on the Conflict of Laws, 8th ed. (Boston: Little Brown, 1883), § 18; J. Moore, A Digest of International Law (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1906), 236; P. Bator, “An Essay on the International Trade in Art,” 34 Stan L. Rev. 275 (1982); this article was also published in book form: The International Trade in Art (Chicago: U. of Chicago Press, 1983).

101. See this chapter’s footnote 96.

102. An earlier case, United States v. Hollinshead, 495 F.2d 1154 (9th Cir. 1974), was similar in nature but did not arouse such interest. Hollinshead, a California art dealer, was arrested for violating the National Stolen Property Act when he was found to possess a pre-Columbian stela allegedly stolen from Guatemala. The prosecution was able to prove that the stela was removed from Guatemala, that the laws of Guatemala vested title to such property in the state, and that Hollinshead was aware of such laws. Hollinshead was convicted, and his conviction was sustained on appeal. Perhaps this case did not create as much controversy as United States v. McClain because Hollinshead involved a stela, a piece readily identified as a choice cultural object and one commonly known to be subject to control by its country of origin. In addition, the stela in question had been documented in situ some years earlier by the noted archaeologist Ian Graham. In McClain v. United States, the objects at issue were movable pre-Columbian artifacts, a category not so readily associated with state control. It is easier to imagine the innocent possession of movable pre-Columbian material than it is the innocent possession of stelae.

103. 18 U.S.C. §§ 2314, 2315, and, regarding the conspiracy charge, 18 U.S.C. § 371.

104. Literally, “friend of the court.” With this status, one who is not a party to a case is granted permission to advise the court on the merits of the case.

105. If Mexican law merely imposed an export tax, a U.S. court would not normally entertain a suit to enforce such a foreign tax. If the foreign law made export a theft, then, as noted before, a U.S. court might entertain a foreign country’s civil suit for the return of the material. Note, however, that McClain was a criminal action to enforce a foreign law.

106. 593 F.2d 658, 665–66. The court was saying, in essence, that the pre-1972 Mexican statutes would not be enforced because under U.S. constitutional standards they were “void for vagueness.”

107. United States v. Schultz, 178 F. Supp 2d 445 (S.D. N.Y., 2002) aff’d 333 F3d 393 (2d Cir. 2003), cert. denied 157 L.Ed. 2d 891 (U.S., 2004).

108. He had appeared at public meetings of the Cultural Property Advisory Committee on behalf of the trade as president of the National Association of Dealers in Ancient, Oriental and Primitive Art, often to argue against the imposition of temporary CCPIA import restrictions. For example, on October 12, 1999, he submitted written testimony before the Open Session of the Cultural Property Advisory Committee Concerning the Application of Italy for protection under the CCPIA in which he stated that “on this request for a complete, country-wide, blanket embargo, we should show them [Italy] ‘tough love,’ deny the request … and work towards a market solution for a market problem.”

109. Ultimately, Tokeley-Parry was caught by New Scotland Yard, convicted in 1997, and served three years in jail. It was Tokeley-Parry who led investigators to Schultz by identifying him as his co-conspirator.

110. Tokeley-Parry and Schultz identified the antiquities as coming from the Thomas Alcock Collection. Thomas Alcock was one of Tokeley-Parry’s deceased relatives. That relationship allowed Tokeley-Parry to present himself as Alcock’s heir for purposes of selling the collection.

111. The fake provenance placed the objects outside of Egypt before applicable laws were enacted.

112. Schultz, 333 F. 3d 393, 416, citing United States v. Leo, 941 F. 2d 181, 197 (3d Cir. 1991).

113. Schultz, 333 F. 3d 393, 415.

114. Schultz, 333 F. 3d 393, 409. The Archeological Institute of America, the American Anthropological Association, the Society of American Archeology, the Society of Historical Archaeology, and the U.S. Committee for the International Council on Monuments and Sites filed amicus briefs arguing that applying the National Stolen Property Act enforced this way would go a long way in protecting archeological sites worldwide.

115. For a discussion of the Schultz case and its application to museum collections, see S. Urice, “Between Rocks and Hard Places: Unprovenanced Antiquities and the National Stolen Property Act,” 40 New Mex. L. Rev. 123 (Winter 2010).

116. Prior to this case, some may have ignored foreign patrimony laws, relying on the 1989 Government of Peru v. Johnson case in which a court held that Peruvian patrimony laws were unclear and akin to export controls, not statutes vesting ownership, and would not be given credence by U.S. courts. After the Schultz case, ignoring or dismissing patrimony laws is nothing short of reckless. See “Culpable Ignorance? Museums Worry about Jury Instructions in Antiquities Conviction Case,” The Art Newspaper, Jan. 9, 2002, accessed Jan. 7, 2005, http://62.253.251.9/access/artnewspaper.html (Record Number 14994).

117. A. Hawkins, “ ‘US v. Schultz’: US Cultural Policy in Confusion” The Art Newspaper, Jan. 9, 2003, http://62.253.251.9/access/artnewspaper.html (Record Number 17370). Fortunately some assistance in locating and translating foreign laws is now available through the International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR). As a result of grants from the Institute of Museums and Library Services (IMLS) and from several private foundations, IFAR established online databases on its “Art Law and Cultural Property” web page. The web page includes two sets of resources: 1) the International Cultural Property/Ownership and Export Legislation (ICPOEL) and 2) Case Law and Statutes (CLS). Also included is Country Contacts, information on the government officials in each country to whom questions may be addressed; http://www.ifar.org/art_law.php. This web page is free but requires a user to provide an e-mail address. (See also the reference to IFAR in Chapter XIV, “Care of Collections,” footnote 15).

118. In the civil context, the Schultz case has additional implications for civil suits. Title to undocumented antiquities can be subject to challenge by countries of origin in civil cases brought in the United States basing ownership on patrimony laws. The burden on a source country seeking restitution in a civil case is to prove ownership via the patrimony law and removal of the state-owned object across its borders after the ownership-vesting statue was enacted. No proof of guilty knowledge of the law in a civil context is required.

119. P. Gerstenblith, “An Internationally Respectful Application of National Law,” The Art Newspaper, Jan. 7, 2004, accessed Jan. 6, 2005, http://62.253.251.9/access/artnewspaper.html (Record Number 19073). The Schultz case is considered a “major setback for the beleaguered US antiquities market.” R. Elia, “A Move in the Right Direction,” The Art Newspaper, Jan. 9, 2003, accessed Jan. 6, 2005, http://62.253.251.9/access/artnewspaper.html (Record Number 17370). It may be anticipated that as a result of the Schultz case countries of origin without patrimony laws in place will now have ample incentive to quickly pass and enforce such laws. In addition, source countries should be increasing their efforts to document antiquities within their borders, including those legally excavated, in private hands and in public collections, so that every undocumented object removed after the enactment of the patrimony law may be identified by default to have been looted from an unexcavated site. Certainly, developments in standardized object identification data collection and digital imaging and text database management will make these documentation efforts easier and more effective in the future. Moreover, the problem that the objects must be traced to have originated within the modern-day borders of a source country may be resolved successfully if bordering countries were to agree to cooperate on such recovery efforts and seek return of objects as joint claimants. See Government of Peru v. Johnson, 720 F. Supp. 810 (C.D. Cal. 1989), aff’d sub nom., Government of Peru v. Wendt, 933 F.2d 1013 (9th Cir. 1991), discussed above, in which Peru’s case would have been significantly stronger had its neighboring countries that had pre-Columbian excavation sites joined in the case. As for international efforts for standardization of object identification data, see this chapter’s footnote 78.

120. For an account of the Italian investigations and where they led, see J. Felch and R. Frammolino, Chasing Aphrodite: The Hunt for Looted Antiquities at the World’s Richest Museum (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011); see also V. Silver, “Lost Art,” Bloomberg Markets 125–132 (Dec. 2005). The Getty allegedly had forty-two objects handled by Medici that match photographs found in the raid of his Swiss warehouse. The Metropolitan Museum of Art allegedly has six objects that match Medici’s photos.

121. The curator, in a statement that was submitted as evidence in her trial, maintained that she followed her museum’s policies and procedures for acquisition, and, indeed, when she first became curator in the mid-1980s, she helped draft a memo to her museum’s board to explore whether it was possible to continue to collect antiquities in a tainted market. V. Silver, “Getty Curator Says Antiquities Trade ‘Corrupt,’ Art Smuggled,” Bloomberg.com, Nov. 10, 2006.

122. In the meantime, Italian authorities filed a civil suit for restitution in Rome that paralleled the criminal prosecution. This suit was dismissed in 2007 as other strategies discussed above for recovery proved fruitful.

123. F. D’Emilio, “Rome: Ex-Getty Curator Trafficking Trial Ends in Italy,” Entertainment News, Associated Press, Oct. 13, 2010.

124. As a result of these negotiations, a number of agreements for return of suspect artifacts between Italian authorities and American museums followed. The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Republic of Italy Agreement was signed Feb. 21, 2006. It agreed to return the famous “hot pot” Euphronius krater, a Hellenistic silver collection, and four other pieces. The Getty signed a similar agreement in August 2007 agreeing to return forty works to Italy. Four of these works, insured for about $425 million, were returned in early October 2007 and will be distributed to Italian museums. But first the works were put on exhibit at the Qurinale Palace in Rome at the end of December 2007. Associated Press Wordstream, “Italy’s Presidential Palace to Host 40 Artifacts Returned from Getty Museum,” Associated Press, Oct. 3, 2007. Princeton University reached agreement on eight artifacts with Italy on October 20, 2007. The Cleveland Museum of Art entered into an agreement with Italy in November 19, 2008, for thirteen antiquities and a late Gothic cross after an eighteen-month negotiation. S. Litt, “Cleveland Museum of Art Strikes Deal with Italy to Return 14 Ancient Artworks,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, Nov. 19, 2008. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston transferred thirteen antiquities to Italy and signed an agreement for cultural exchange on September 28, 2006. Press Release, “Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and Italian Ministry of Culture Sign Agreement Marking New Era of Cultural Exchange: MFA Transfers 13 Antiquities to Italy” (Sept. 28, 2006), accessed May 6, 2011, http://www.mfa.org/collections/art-past/italian-ministry-culture-agreement. The University of Virginia returned two ancient sculptures in 2008. See J. Kreder, “The Revolution in U.S. Museums Concerning the Ethics of Acquiring Antiquities,” 64 U. Miami L. Rev. 997, 1010 (Apr. 2010). In 2002, at the beginning of the restitution movement, a statement was issued by the world’s largest museums in possession of antiquities, called “The Universal Museum Statement,” in which they were essentially justifying museum collecting. C. Bohlen, “Major Museums Affirm Right to Keep Long-Held Antiquities,” New York Times, Dec. 11, 2002.

125. Not all the texts of these agreements were made public, but reportedly all the agreements address museum practices for future acquisitions. The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s agreement, which was released, states that “all collecting will be done with the highest criteria of ethical professional practice.” The text of the agreement is reproduced online at http://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/HL0602/S00265.htm, accessed Aug. 8, 2011. Reportedly, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston agreement went further in that the museum agreed to inform the Italian Ministry of Culture of any future acquisitions, loans, or donations of objects that could have an Italian origin. See E. Povoledo, “Boston Art Museum Returns Works to Italy” New York Times, Sept. 29, 2006, accessed Aug. 8, 2011, http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C01EFD91630F93AA1575AC0A9609C8B63&pagewanted=1.

126. S. Urice, “Between Rocks and Hard Places: Unprovenanced Antiquities and the National Stolen Property Act,” 40 New Mex. L. Rev. 123 (Winter 2010), n.2. The warrants alleged that several museums participated in one or more illegal activities, including tax fraud conspiracy to inflate the value of donated objects and possession of antiquities stolen from China, items stolen from Thailand, illegally imported antiquities from Burma, and Native American resources removed from public lands without a permit.

127. S. Urice, “Between Rocks and Hard Places,” 148–149.

128. S. Urice, “Between Rocks and Hard Places,” 149–151.

129. F. Goldstein, “Introduction: Cultural Property and Provenance: What’s New about What’s Old,” in American Law Institute–American Bar Association (ALI-ABA), Course of Studies Materials: Legal Issues in Museum Administration (Philadelphia: ALI-ABA, 2009).

130. In the confirmation of the UNESCO Convention, the Senate specifically noted that it was not the intention of Congress to enact legislation to control the acquisition policies of museums generally. This “reservation” was directed to Article 7(a) of the convention:

The State parties to the Convention undertake:

(a) to take the necessary measures, consistent with national legislation, to prevent museums and similar institutions within their territories from acquiring cultural property originating in another State Party which has been illegally exported after entry into force of this Convention, in the States concerned. Whenever possible, to inform a State of origin Party to this Convention of an offer of such cultural property illegally removed from that State after the entry into force of this Convention in both States.

In the opinion of Congress, museums would voluntarily conform their policies to meet the standards expressed in the convention. In fact, professional organizations did begin to issue position papers urging their members to put into practice the principles underlying the convention, and some institutions quickly responded with actual policies.

See the “Report of the Special Policy Committee of the American Association of Museums,” as reported in Museum News (May 1971). The committee submitted to the Council of the American Association of Museums recommendations on the proposed UNESCO Convention. In 1973, the American Association of Museums, the College Art Association, the Archeological Institute of America, the U.S. Committee of the International Council of Museums, the Association of Art Museum Directors, and the American Anthropological Association joined in adopting and promulgating a resolution that stressed the ethical and professional responsibilities of museums to support the principles of the UNESCO Convention. The Code of Ethics for Art Historians, adopted by the College Art Association as of January 24, 1995, gives more information on this resolution.

The first museum to announce an acquisition policy of this nature was the University of Pennsylvania Museum on April 1, 1970. Besides Harvard University and the Smithsonian Institution discussed above, others included the California State University at Long Beach; the Field Museum; Southern Illinois University; Washington State Museum in Seattle; Peabody Museum in Salem, Massachusetts; Arizona State Museum in Tucson; and the Utah Museum of Natural History. See P. Bator, The International Trade in Art (Chicago: U. of Chicago Press, 1983, Midway reprint ed., 1988), n.144. Notably absent from this original list are major private art museums. To the author’s knowledge, there have been no studies to evaluate the implementation of these policies.

131. This was in spite of a resolution on museum acquisitions issued in January 1973 by the American Association of Museum Directors (AAMD), whose membership includes the directors of major American art museums, urging its members to cooperate fully with foreign countries to prevent the illicit traffic in works of art. The AAMD resolution was adopted on January 23, 1973, and published in an article, “The AAMD Takes a Stand,” Museum News 49 (May 1973). This resolution confirmed the belief of the AAMD that art museums can best implement such goals by refusing to acquire objects in violation of the relevant laws “obtaining in the countries of origin” and specifically recommending to boards of art museums that they promulgate “an appropriate acquisition policy statement.”

132. Association of Art Museum Directors, “A Code of Ethics for Art Museum Directors as Adopted by the Association of Art Museum Directors in 1981,” in Professional Practices in Art Museums: Report of the Ethics and Standards Committee (New York: Association of Art Museum Directors, 1981 AAMD Code).

133. By contrast, the position of archaeologists shared by source nations is that an unprovenanced antiquity of museum quality can be presumed to be the product of illicit looting. Acquisition by museums of unpro v - enanced objects fuels such activity that leads to the irretrievable loss of knowledge and destruction of sites (including other less market-desirable objects) resulting from unscientifi c excavation. S. Urice, “Antiquities as Cultural Property: Dealing with the Past and Looking to the Future,” in American Law Institute—American Bar Association (ALI-ABA), Course of Studies Materials: Legal Problems of Museum Administration (Philadelphia: ALI-ABA, 2007) 23, 26. Note also that these guidelines technically would have permitted the acquisition of an object that was merely illegally exported, as opposed to “stolen.” A justifi cation for the lack of compliance to foreign export controls was the belief that export regulations of source countries are in effect an embargo on trade as export permits are rarely, if ever, issued. As implemented, such foreign export controls are contrary to U.S. policies that support free trade in cultural goods.

134. Association of Art Museum Directors, “A Code of Ethics for Art Museum Directors as Adopted by the Association of Art Museum Directors in 1992,” in Professional Practices in Art Museums: Report of the Ethicsand Standards Committee (New York: Association of Art Museum Directors, 1992 AAMD Code). The 1992 AAMD Code declared that it is unprofessional for art museum director members

(C) To acquire knowingly or allow to be recommended for acquisition any object that has been stolen, removed in contravention of treaties and international conventions to which the United States is a signatory, or illegally imported into the United States.

This provision refers to U.S. laws, treaties, and conventions as limited by U.S. laws only. Note that the 1989 Government of Peru v. Johnson case that was decided three years before the AAMD issued this revised policy may have influenced this change as that case was often cited for the proposition that broad foreign patrimony laws that declared all cultural property to be state owned would not necessarily be recognized as valid proof of ownership by U.S. courts. Decision makers may have concluded (with some risk as it turns out) that the concerns of foreign patrimony laws could be dismissed after an object had entered the United States and had come under U.S. jurisdiction. In other words, the object need not be considered “stolen” if it was taken in violation of a foreign patrimony law because U.S. courts would probably not define theft in that way.

135. Under both the 1981 and the 1992 versions of the AAMD Code, the absence of information about an object would not work to prevent its acquisition, as only “actual knowledge” of theft would suffice. Such a standard invites a blind eye, which in turn leaves no margin for error. American art museums were seemingly content to protect themselves from financial damage when buying unprovenanced objects by requiring written warranties from “reputable dealers” who could be found later to pay up if it should prove to be necessary to invoke warranties, although the AAMD codes did not specifically require warranties. Note that in the event any director member of AAMD violates these guidelines on professional conduct, he or she can be reprimanded or dismissed from the organization and the director’s museum can be subject to sanctions such as suspension of loans or shared exhibitions. To the authors’ knowledge, no reprimands or expulsions have been reported for errant acquisition practices.

For example, from 1987 to 1995, the Getty policy required warranties from dealers that included warranties of clean title, of legal export, and that all other customs and patrimony laws, regulations, and requirements of all relevant countries had been met. The J. Paul Getty Museum Acquisition Policy for Classical Antiquities, November 13, 1987, states that “[a]ll transactions will be with vendors of substance and established reputations in order that such transactions shall be covered by enforceable warranties.” Presumably “reputable dealers” could be located should a problem arise and would have the financial capacity to make good on the warranty. The AAMD published a new version of its Professional Practices in Art Museums in 2001. In that document, for the first time, there is a provision directing investigation of provenance as a step in the acquisition process: “The director must ensure that best efforts are made to determine the provenance of a work of art considered for acquisition” (Paragraph 18). No further guidance is given.

136. For the application of these guidelines to a hypothetical collection, see I. DeAngelis, “How Much Provenance Is Enough: Post Schultz Guidelines for Museum Acquisition of Archeological Materials and Ancient Art,” B. Hoffman, ed., Art and Cultural Heritage: Law, Policy and Practice (Cambridge: Cambridge U. Press, 2006) 398–408.

137. For an excellent discussion of the similarities and differences between the two policies, see S. Cott and S. Knerly, “Comparison of the Report of the AAMD Task Force on the Acquisition of Archaeological Material and Ancient Art (revised 2008) and the American Association of Museums Standards Regarding Archaeological Material and Ancient Art (July 2008),” in American Law Institute–American Bar Association (ALI-ABA), Course of Studies Materials: Legal Issues in Museum Administration (Philadelphia: ALI-ABA, 2009).

138. Accessed Apr. 4, 2011, http://aamdobjectregistry.org.

139. See the new Getty policy issued in 2006: “Policy Statement: Acquisitions by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Adopted by the Board of Trustees of the J. Paul Getty Trust on October 23, 2006,” Fig. IV.10. A moratorium on the acquisition of undocumented antiquities was also declared by the Indianapolis Museum of Art (IMA) on April 16, 2007, which will remain in effect while the IMA “evaluates and reframes” its current policies on the collection of antiquities and ancient art. “[W]e hope it will be a small step towards stemming the tide of illegal excavation or clandestine removal of accidentally discovered objects from countries the world over,” said IMA director and CEO Maxwell Anderson in an internet posting on April 30, 2007; accessed May 6, 2011, http://www.elginism.com/20070430/723/. The IMA subsequently adopted the changes outlined in the new 2008 AAMD guidelines. So did the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In June 2008 the Executive Committee of the Board of Trustees of the Metropolitan Museum of Art formally accepted the AAMD 2008 Report of the AAMD Task Force on the Acquisition of Archaeological Materials and Ancient Art, and on November 12, 2008, the Board of Trustees adopted a revised Collections Management Policy incorporating those guidelines; accessed May 9, 2011, http://www.metmuseum.org/press_room/full_release.asp?prid={85EDA1CD-A74C-447A-9D2A-1494592D9256}. Some museums have created checklists for provenance research. See F. Goldstein, “Provenance Checklist and Questionnaire for Acquisitions,” in American Law Institute–American Bar Association (ALI-ABA), Course of Studies Materials: Legal Issues in Museum Administration (Philadelphia: ALI-ABA, 2009).

140. 140. Accessed May 30, 2011, http://www.aamd.org/newsroom/documents/2008ReportAndRelease.pdf

141. Sotheby’s held two successful antiquities auctions in 2007. The objects that sold well and for high prices were well known and documented to have been outside of the country of origin for a long time. T. Kline, “Art Market,” in S. Hutt, ed., Yearbook of Cultural Property Law 2008 (Walnut Creek, Calif.: Left Coast Press, 2008), 107.

142. See C. Coggins, “A Proposal for Museum Acquisition Policies in the Future,” 7 Int’l J. of Cult. Prop. 434–437 (1998).

143. I. DeAngelis, “An Interview with Italian Prosecutor Paolo Ferri in Rome, Italy, March 2007,” in S. Hutt, ed., Yearbook of Cultural Property Law 2008 (Walnut Creek, Calif.: Left Coast Press, 2008), 11–31.