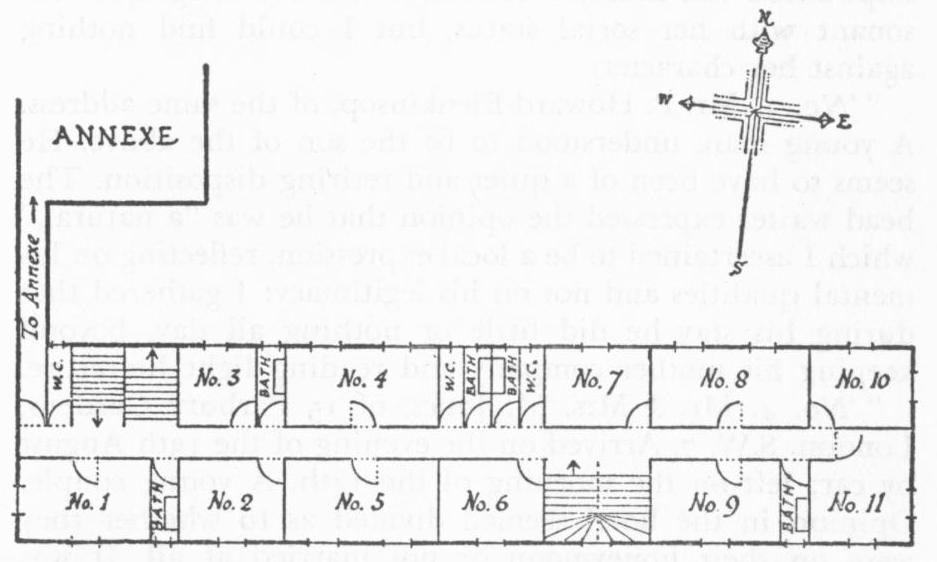

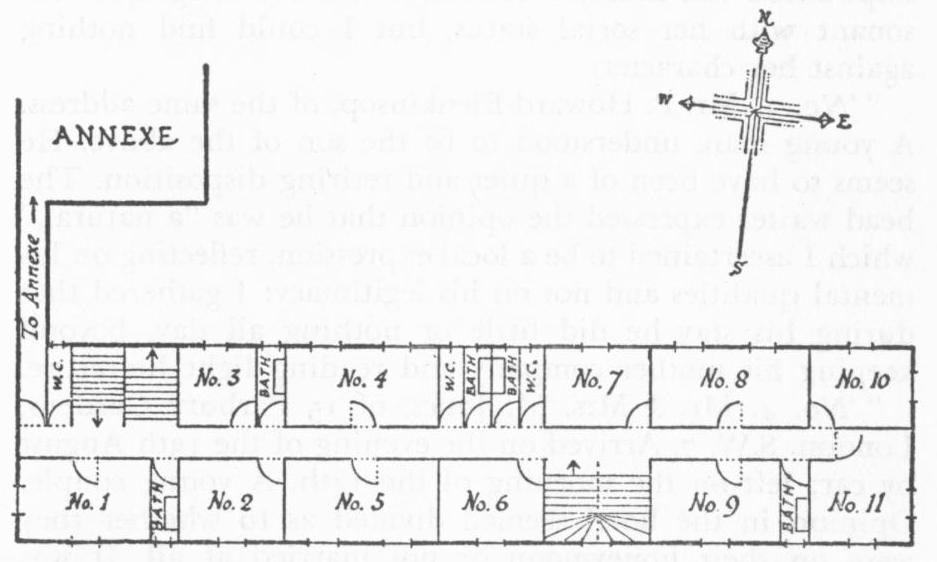

Sketch Plan of the First Floor of Pendlebury Old Hall, Markshire

The three days which Jas. Elderson had allowed himself to complete his inquiries at Pendlebury were past. The first post on the morning of the fourth brought only bills and circulars to Plane Street. Stephen and Anne looked at each other silently and disgustedly across the breakfast-table. There was no need for words. The fellow had let them down. The moment when they would be able to do something towards the investigation of the mystery was once more postponed, and for how long? Each of them realized for the first time how great the strain of waiting had been, and how insufferable was the prospect of bearing much more of it.

“Of course,” said Anne, speaking for the first time that morning, “I always thought three days was rather a short time to allow himself. But if he found it wasn’t enough, he ought to have given us an interim report—something to go on with, at least.”

“Um,” said Stephen, and said no more.

Immediately after breakfast he went out, asking Anne to await his return at the house. The weather had broken, and a gusty south-west wind was driving thin showers of rain before it. The skirts of his mackintosh wrapped themselves around his trouser legs in an embrace that became progressively damper and more affectionate as he walked. It was a depressing day, and even the warm synthetic air of the Underground was welcome in contrast to the outside world.

Stephen had to ring twice at the door of Jas. Elderson’s office before receiving any answer. When at last the door was opened, he found himself looking into the large grey eyes of a totally unknown young woman. She was undeniably good-looking, tall above the average, and somewhat dauntingly self-possessed. For a moment, recollecting the uncouth and grimy office-boy who had received him on the last occasion, he wondered whether he had stopped at the wrong landing, and he endeavoured to look past her to reassure himself by reading the name upon the door. He was aware as he did so that she was observing his embarrassment with a certain calm amusement.

“Do you want anything?” she asked, just as he had made up his mind that he was right after all. Her voice, without being particularly cultured, was quiet and pleasing.

“Is Mr. Elderson in?” said Stephen.

“I’m afraid he’s not available today,” was the reply. “Monday, I expect. In fact, I’m sure he’ll be available all Monday.”

“I particularly wanted to see him today,” Stephen persisted. “Do you know where I could get hold of him, perhaps?”

She shook her head.

“Not today,” she repeated. “Perhaps I can help you. What name is it?”

“Dickinson.”

Her face cleared.

“Oh, Mr. Dickinson! Have you come about the Pendlebury matter?”

“Yes. Mr. Elderson promised me his report this morning, and I haven’t had it. He knew that it was extremely urgent, and I—”

“Will you come inside?” she said, and stood on one side to let him pass. She closed the door behind him and then said: “If you don’t mind waiting here a moment, I’ll see whether it is ready for you.”

Stephen waited in the narrow little hall while she went through into the passage within. Presently she returned, with an odd expression on her face which he tried in vain to interpret.

“I’m afraid you’ll have to come in here to help me,” she observed, and led the way into the office.

Mr. Elderson was sitting at a table littered with sheets of paper. His arms were spread out in front of him and his head was pillowed on his arms. He was breathing deeply and from time to time uttering a loud snore. A completely empty whisky bottle was beside him and a glass lay broken on the floor. The stench of spirit and stale tobacco smoke lay heavy upon the air.

“You see,” said the young woman, calmly, “the trouble is that he’s sitting on a lot of the papers. And he’s too heavy for me to move. If you wouldn’t mind lifting him up a bit, I could slide the chair out from underneath him and get them, and then put it back again.”

Under her tranquil influence it seemed the most ordinary operation in the world. With his left hand pressing on Mr. Elderson’s back and his right hand heaving at Mr. Elderson’s fleshy thighs, Stephen contrived to shift him upwards and forwards just enough to allow her dexterously to disengage the chair, sweep from it the warm and crumpled papers upon the seat and replace it before Stephen’s aching muscles gave under the strain. During this process, Mr. Elderson muttered a few inarticulate words of protest and as soon as it was completed was sound asleep once more.

“Thanks,” she said. “I think I’ve got it all now.” She gathered up the sheets from the table and added them to those recovered from the chair. “I’ll just arrange them in order. Luckily he always numbers his pages. Shall I put them in an envelope for you?”

“Yes—please do,” Stephen gasped. “But is it—I mean, how do you know—is it all right, I mean?”

She paused in the act of licking the flap of a large square envelope.

“All right?” she asked. “Oh, the report, you mean. Yes, that will be all in order, you’ll find. He never starts on that”—she nodded towards the bottle on the table—“until he’s finished the job. It’s a kind of reaction, you see. The only trouble is that when he starts he never knows where to stop. That’s why . . .” She shrugged her shoulders and left the sentence uncompleted. “He got back pretty late from Pendlebury yesterday and must have been working here nearly all night.” She held out the envelope to him. “Here you are, Mr. Dickinson,” she said, in a tone that seemed to indicate some haste to be rid of him. “I’m sorry you’ve had the trouble of coming down here.”

Stephen took the envelope and stuffed it into the pocket of his mackintosh.

“Thank you,” he said. “But”—he looked once more at the sprawling creature at the table—“are you going to stay on here alone? I can’t get you any help or anything?”

Her mouth straightened into a hard, narrow line.

“No, thank you,” she said. “I shall be quite all right. Let me show you out.”

On the doorstep, Stephen said: “Well, goodbye, and thank you for helping me, Miss—er—Miss—”

“Elderson,” she said sharply, and shut the door.

As he had expected, Stephen found Martin with Anne when he returned home. They were in the study, Martin deep in the arm-chair in a cloud of acrid smoke, while Anne crouched at his feet on a foot-stool in an attitude of adoration.

“Morning, Steve,” said Martin without getting up. “Nuisance about this detective feller. Annie’s just been telling me.”

“Did you manage to see him?” Anne asked.

“Oh, yes. I saw him all right,” said Stephen.

“What had he got to say for himself?”

“He hadn’t exactly a great deal to say for himself. But I’ve got his report.”

Martin, as Stephen feared he would do, greeted the news with “Good egg!” and added, “Does it amount to much?”

“That,” said Stephen, “is what we are now going to see.”

He produced the envelope, still sealed, and began to open it. To his extreme annoyance he found his fingers trembling as he did so and for a moment or two he fumbled helplessly with the flap.

“Yes,” observed Martin, watching him. “It is rather an excitin’ moment, isn’t it?”

Stephen, once more caught unawares by his prospective brother-in-law’s penetration and annoyed by finding himself its victim, frowned hideously and at last succeeded in tearing the envelope and removing the contents. Written in a large copper-plate hand that flowed generously over sheet after sheet of ruled foolscap paper, these proved at a glance that Miss Elderson’s account of her father’s habits was correct. There could be no doubt that they were the work of a man who, at the time of writing them, was stone-cold sober. He smoothed out the pages where they had been crumpled by the pressure of their author’s large posterior, cleared his throat, and began to read.

The document was headed in the starchy official manner that was no doubt a relic of the author’s police service: “ ‘To Stephen Dickinson, Esq. From Jas. Elderson, private inquiry agent. Re Occurrence at Pendlebury Old Hall Hotel, Markshire.’ ” It continued, in numbered paragraphs:

“ ‘1. Pursuant to your instructions of the 22nd inst., I proceeded forthwith to Pendlebury Old Hall Hotel, arriving there at approximately 8.30 p.m. I registered in the name of Eaton, and, the hour being somewhat late to commence prosecuting inquiries, occupied myself during the evening with familiarizing myself with the hotel staff and ascertaining the geography of the place.’ ”

“Funny phrase, that,” remarked Martin. “I don’t suppose he means the same thing as we generally mean by it, eh, Steve?”

“Shut up, you ass,” said Anne softly.

“ ‘2. During the succeeding two days, I succeeded in interviewing all the members of the hotel staff who appeared likely to be of any assistance, in inspecting the hotel register and obtaining their comments upon the same. I prolonged my stay at the hotel for the purpose of taking a statement from one important witness, the waitress Susan Carter, who was on her holiday and only returned to work on the morning of the 25th inst. I found all the persons interviewed quite willing to give me all the information within their power. The explanation of this fact, which was contrary to my anticipation and to past experience in like matters, appeared to be due—’

“Lord! What English this blighter writes!” said Stephen, breaking off. “Damn all board schools!”

“Don’t be a prig,” said Anne. “Go on.”

“ ‘—appeared to be due to their mistaken belief that I was acting in the interests of the British Imperial Insurance Company. It transpired that a representative of that concern had already visited the Hotel and made inquiries with a view to possible litigation. By representing to the persons concerned that the interests of the establishment coincided with those of the Company in suppressing any further publicity attaching to the death of the late Mr. Dickinson, and, as I have reason to believe, by a lavish disbursement of funds, the representative had succeeded in securing their whole-hearted co-operation. I thought it wise not to undeceive the persons in question as to my identity and was accordingly able to secure the maximum of information with the minimum of outlay (as to which, see Exes sheet, forwarded to Messrs. Jelks & Co., pursuant to instructions).

“ ‘3. The only other preliminary matter which I should mention is that on the last day of my residence at the Hotel an individual whom I have reason for thinking to be a plain-clothes detective of the local constabulary also arrived and commenced to make inquiries, which I was able to ascertain were related to the matter in question. In consequence of the facts set out in Para. 2, above, the personnel of the Hotel were unwilling to give the individual whom I have mentioned any assistance, but I am unable to state precisely what form his inquiries took or how far the same were successful.’ ”

“The insurance blokes haven’t wasted much time, have they?” Martin observed. “But what are the police poking about for? I thought you said, Steve, that they wouldn’t touch this thing with a barge-pole?”

“I hope I never said anything so banal,” answered Stephen curtly, preparing to read on.

“But wait a bit,” said Anne in some excitement. “This is important, isn’t it? If the police are making inquiries, doesn’t that look as if they weren’t satisfied with the inquest verdict after all?”

“Whether it’s important or not,” said her brother crossly, “do you want to hear what this man has to say? Or shall I take it away and read it to myself?”

Sketch Plan of the First Floor of Pendlebury Old Hall, Markshire

After which little display of temper, the reading continued without further interruption:

“ ‘4. The hotel consists of three floors only, having been originally constructed as a private residence. The guests’ bedrooms are all accommodated on the first floor, the ground floor rooms being sitting-rooms and the second or attic floor comprising the apartments of the chambermaids and waitresses. There is also an annexe for additional accommodation. I formed the impression that business at the establishment was not brisk, for the annexe was wholly unoccupied at the time in question, and of the eleven bedrooms in the main building two were vacant. I append a sketch-map showing the position of the various rooms, all of which, it will be observed, open off a central corridor, which runs the length of the house.

“ ‘5. On the night of the 13th August, to which I was directed to confine my attention, the following rooms were occupied, as under:

“ ‘No. 1. Mr. & Mrs. E. M. J. Carstairs, of 14 Ormidale Crescent, Brighton. Arrived on the 12th August by car; left on the 14th after lunch. A middle-aged couple. The only details that I was able to obtain concerning them were that Mr. Carstairs was interested in local antiquities, and delayed his departure in order to obtain a rubbing of the brasses in Pendlebury church.

“ ‘No. 2. Mrs. Howard-Blenkinsop, of The Grange, North Bentby, Lincs. Arrived on the 5th August; being met at the station by the hotel conveyance, left on the 19th August. An elderly lady, presumed to be a widow. Well known in the hotel, where she makes a habit of staying for a fortnight in each year, though not always at the same time of year. Mention of her name caused some amusement to the staff. I gathered that her character was in some degree peculiar, and the head housemaid went so far as to say that “she acted unusual for a lady.” So far as I was able to determine, the imputation was that her behaviour was not altogether consonant with her social status, but I could find nothing against her character.

“ ‘No. 3. Mr. P. Howard-Blenkinsop, of the same address. A young man, understood to be the son of the above. He seems to have been of a quiet and retiring disposition. The head waiter expressed the opinion that he was “a natural,” which I ascertained to be a local expression, reflecting on his mental qualities and not on his legitimacy: I gathered that during his stay he did little or nothing all day, beyond keeping his mother company and reading light literature.

“ ‘No. 4. Mr. & Mrs. M. Jones, of 15 Parbury Gardens, London, S.W. 7. Arrived on the evening of the 13th August by car; left on the morning of the 14th. A young couple. Opinion in the hotel seemed divided as to whether they were on their honeymoon or not married at all. It was agreed that their behaviour was “lover-like.” The reception clerk recollected that the girl giggled a good deal while the register was being signed. I could not obtain any exact description of either, except that she was, in the words of the chambermaid, “a flash little thing” and he was “nothing much to look at, but acted like a gentleman.” I formed the opinion that this referred to the size of her gratuity. I ascertained that they reached the hotel at about 8.30 p.m. while dinner was being served, and had some cold food sent up to their room on a tray about 9.0 p.m. The waitress who served them remembered the occasion particularly well, because of the extra trouble involved. She also recollected that they breakfasted in bed next morning, at about the time that the disturbance occasioned by the death of Mr. Dickinson was at its height.

“ ‘No. 5. Vacant.

“ ‘No. 6. Mr. J. S. Vanning. See as to this gentleman, remarks re Mr. Parsons, below.

“ ‘No. 7. Mr. J. Mallett. I am instructed that this individual is already known to you.

“ ‘No. 8. Vacant.

“ ‘No. 9. Mr. Robert C. Parsons. Arrived for tea on the 13th by cab from the station; left on the morning of the 14th. A middle-aged man. He is particularly well remembered by the office staff for the reasons following, viz.: He had reserved accommodation by letter, asking for a room with two beds and a single room, adjoining if possible. Room 9, which is a double room, and No. 11, next to it, had accordingly been reserved for him. Some surprise was therefore expressed when he appeared by himself. He explained that he suffered very badly from insomnia, and had found that he could obtain some relief by changing from one bed to another during the course of the night; hence his desire for a double room. The other room, he said, was for a friend who would be joining him later. The reception clerk remembered that when she asked the name of the friend he was unable or unwilling to give it, but merely said that he would be mentioning his (Mr. Parson’s) name. Mr. Parsons was shown his room and No. 11, adjoining, which is the best single room in the house. He expressed himself as pleased with them. A little later, however, Mr. Leonard Dickinson arrived at the hotel, on foot. He was of course well known to the management, having stayed there on numerous occasions. It was also understood that whenever he visited the hotel, room No. 11, if not occupied, should be kept for him. Indeed it had happened in the past that guests had been asked to change their rooms to suit Mr. Dickinson, who was, it is alleged, apt to make difficulties when crossed in any way. In this instance, No. 11 not being actually occupied, Mr. Dickinson was installed there, and on Mr. Parson’s guest arriving (by car, shortly before dinner), he was put into No. 6, being the only vacant single room. The guest registered in the name of J. S. Vanning, and the only address given was London. Mr. Parsons similarly gave no address, other than the town of Midchester. I was, however, able to get a sight of his letter reserving the rooms, and this was written on the note-paper of the Conservative Club of that city. There seems no doubt from what I was told that Mr. Parsons was in poor health. More than one witness remarked on his pallor and nervousness. As to Mr. Vanning, I could obtain no particulars whatever. He does not seem to have had any noticeable features at all. I should add that the two persons in question did not leave the hotel together. Mr. Vanning breakfasted early and left soon after 8 a.m. Mr. Parsons did not come down till later and seemed surprised and upset that his friend had already gone. It was pointed out to him, however, that Mr. Vanning had settled his own account. I was unable to ascertain whether this fact reassured him or not.

“ ‘No. 10. Mr. Stewart Davitt, of 42 Hawk Street, London, W.C. Arrived the 10th August, by train and hotel conveyance; left on the 14th by the same. This gentleman was described to me by one of the staff as “the mystery man.” It appears that from the time of his arrival up to his departure he did not go outside the hotel, and, indeed, only rarely left his room. He is said to have explained that he was engaged upon work of a vitally important character and needed absolute rest and quiet. All his meals were served in his room. I was told that he was “a nice-looking young man,” but could obtain no further particulars of his appearance. On the evening of the 13th, he asked for his account, and said that it would be necessary for him to catch the earliest fast train to London from Swanbury Junction, some eight miles away. This involved his leaving the hotel at approximately 6.30 a.m. the next morning, which he duly did, being driven to the station by the car attached to the hotel. In view of the decidedly unusual circumstances attending this person, I endeavoured to obtain further particulars concerning him, but without success. I was unable to ascertain anything re his work, about which, it seems, he was extremely reticent. It is to be presumed that it was of a literary nature.

“ ‘No. 11. Mr. Leonard Dickinson.

“ ‘6. The above information comprises all that I was able to ascertain re the matters to which my instructions were confined. I took the liberty, however, of pursuing my investigations somewhat further, with a view to discovering any matter which might throw light on the death of the deceased. I therefore venture to append the following.

“ ‘7. The deceased retired to bed on the night of the 13th August, at approximately 10.45 p.m. Before doing so, he went to the reception office and asked (a) that a pot of china tea with a slice of lemon should be sent up to his room in about a quarter of an hour’s time, and (b) that his breakfast should be served to him in bed the next morning at 9.0 a.m. (a) was duly performed; it was when he was called next morning prior to (b) that his death was discovered. Death was found to be due to the deceased having swallowed a quantity of Medinal overnight. These matters were, I am given to understand, investigated in the ordinary way at the inquest, the assumption being that the deceased took the fatal dose in the tea. This remained an assumption only, due to the fact that the teapot and cup had been removed and washed before the fact of death was discovered. It seemed to be a reasonable one, however, and I deemed it desirable to proceed upon the basis that it was correct, the question being whether anybody other than the deceased could have inserted the poison in the tea.

“ ‘8. I accordingly proceeded to question the two persons who seemed most likely to assist on this question, viz. Miss Rosie Belling, chambermaid, and Miss Susan Carter, waitress (whom I have already mentioned, supra, Para. 2). Miss Belling was not very helpful. All that she could say was that at approximately 8.15 a.m. on the morning of the 14th August she went into room No. 11 and removed from it the tray with the teapot and cup upon it. Mr. Dickinson having given orders for breakfast in bed at 9.0 a.m., she would not normally have gone into his room at that hour, but for the fact that, several other guests having demanded tea in the morning, there was a shortage of tea-sets, following an accident on the staircase two mornings before. On this occasion, seeing the deceased apparently still asleep, she merely removed the tray and went out again without attempting to disturb him. On returning, shortly before 9.0 a.m., to inquire whether he was ready for breakfast, the fact of his death was ascertained, by which time the teapot and cup had been washed and used by another guest.

“ ‘9. Miss Carter’s evidence at the inquest was confined to the fact that she took a tray up to the deceased’s room on the night in question. In answer to my inquiries, however, she was able to describe her movements in very much more detail. It appears that this particular evening was an unusually busy one for her, so far as work upstairs was concerned. For besides taking the tea-tray to No. 11, she also had to take up dinner as usual to Mr. Davitt (No. 10), supper to Mr. and Mrs. Jones (No. 4) and hot water, sugar, lemon, and whisky to Mr. Vanning (No. 6). In fact, she had somewhat of a grievance re the amount of fetching and carrying that had to be done, especially in regard to No. 4, for it appears that these persons, having originally ordered a meal downstairs, changed their minds at the last moment. So far as I was able to ascertain, she visited the bedroom floor of the hotel four times during the course of the evening, as follows:

“ ‘8.15 p.m. Taking dinner to No. 10.

“ ‘9.0 p.m. Taking supper to No. 4, and removing dinner-tray from No. 10.

“ ‘10.0 p.m. Removing supper-tray from No. 4.

“ ‘11.0 p.m. Taking tea to No. 11 and hot water, etc. to No. 6.

“ ‘10. I asked Miss Carter whether she had observed anything unusual in the manner of the deceased on bringing him his tea, and in reply she stated that on that occasion she had not seen him at all, but had only heard his voice. She explained that from her previous experience of the deceased, upon whom she had waited during several former visits of his to the hotel, she knew him to have a particular distaste to the presence of anybody, particularly any female, in his bedroom when he was, or might be, incompletely attired. Accordingly she merely knocked at the door, informed him of the fact that his tea was awaiting him and went away, leaving the tray in the corridor. Asked whether she had followed the same procedure in the case of Mr. Vanning she professed difficulty in recollecting the same, but finally stated that she was of opinion that on her knocking at his door he had himself opened it and taken the tray from her hand.

“ ‘11. In view of the obvious significance of the facts stated in Para. 10 above, I deemed it advisable to inquire as to who of the residents in the hotel were in their rooms at the time when the tray was left outside No. 11. Miss Carter, having ascended to the first floor from the kitchen premises by the service staircase, was unable to state who was still in the lounge or smoking-room on the ground floor, and apart from Mr. Vanning, she saw nobody on the first floor at that time. One of the bathrooms was being used as she passed along the corridor, but she was unable to say which it was. The remainder of the staff were uncertain in their recollection on the point, but by collating all the evidence available, I was able to arrive at the conclusion that the following were at 11.0 p.m. almost certainly in their rooms:

Mr. Vanning.

Mr. Dickinson.

Mr. Davitt.

Mr. & Mrs. Jones.

Mr. Parsons.

“ ‘The following were in all probability in their rooms:

Mr. Howard-Blenkinsop.

Mrs. Carstairs.

Mr. Mallett.

“ ‘As to the remainder, Mrs. Howard-Blenkinsop sat on in the lounge after her son had gone to bed, endeavouring to finish a game of patience, and Mr. Carstairs, after retiring at the same time as Mrs. Carstairs, shortly returned again to the lounge, where he gave some assistance to Mrs. Howard-Blenkinsop in her game. I was able to ascertain positively that the lights were extinguished before midnight, and that these two individuals were the last to retire.

“ ‘12. With regard to the management and staff, I was unsuccessful in obtaining any information to the detriment of these. The deceased appears to have been regarded as an asset to the establishment rather than otherwise, and I could not find any evidence suggesting that a motive was present for procuring his death so far as they were concerned. They appeared to be a respectable body of individuals, though in some respects deficient from the viewpoint of efficiency.

“ ‘13. The above concludes my inquiries at Pendlebury Old Hall Hotel, and I await further instructions.

“ ‘(Signed)

“ ‘Jas. Elderson.’ ”