YOU ARE ALL sons of God through faith in Christ Jesus, 27for all of you who were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. 28There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. 29If you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise.

4:1What I am saying is that as long as the heir is a child, he is no different from a slave, although he owns the whole estate. 2He is subject to guardians and trustees until the time set by his father. 3So also, when we were children, we were in slavery under the basic principles of the world. 4But when the time had fully come, God sent his Son, born of a woman, born under law, 5to redeem those under law, that we might receive the full rights of sons. 6Because you are sons, God sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, the Spirit who calls out, “Abba, Father.” 7So you are no longer a slave, but a son; and since you are a son, God has made you also an heir.

Original Meaning

IN THE BROADER context of the book of Galatians, our section is the third argument Paul offers to the Galatians for his view that (1) both acceptance with God and the continuance of a relationship with him are (2) based on faith (3) for people of all kinds, and (4) not on doing works of the law to perfect that relationship. He had stated his whole theory in 3:1–5. His first argument was rooted in the Old Testament (vv. 6–14), and his second argument was an “example from everyday life” (vv. 15–25). This third argument is from “sonship,” which contains another “example from everyday life” (4:1–2) and ends with a pastoral appeal to agree with him (4:8–20). This appeal will be the focus of our next chapter.

Essentially, the argument from sonship may be put like this: (1) Faith in Jesus Christ makes a person a “son of God,” and this obtains for everyone (3:28); (2) being a “son of God” means that a person is also a member of Abraham’s seed, because one becomes associated with Christ, who is the Seed of Abraham (v. 29). Since believers are members of Abraham’s seed, (3) they are also “heirs according to the promise” (3:29). This connection, faith → son of God → Abraham’s seed → heir of the promise, is then explained and illustrated further by appealing to the human institution of a son becoming an adult male and, as an adult male, inheriting the father’s promise. Such an analogy compares to the history of Israel: when Israel was under the law, Israel could be compared to a “slave-like” son, who was still immature and unable to enjoy the benefits of adulthood. But when Israel became an adult male (i.e., when God fulfilled his designs through Christ), Israel was set free from its slavery to the law, so that Israel might become a son with full privileges (and Gentiles would be included too). Throughout this entire argument Paul emphasizes universalism (cf. 3:26–28): the Judaizers had restricted God’s acceptance to those who were Jews or who would join Judaism by following the works of the law; Paul says that God accepts all on the basis of faith in Christ.

I believe Paul’s argument is rooted in the early Christian baptismal experience (cf. v. 26) of learning, by faith, to call God “Father” (cf. 4:6–7 with 3:26–27). Such an experience makes one conscious of being a son of God. On this basis, Paul argues that sonship implies something: being an heir of Abraham and of his promises. This is Paul’s polemical point: if you are a son of God by faith (and you know this by the experience of calling God “Father”), you are also an heir of the covenantal promises to Abraham; you have become an heir by faith, not by observing the law. Once again rooting his point in their experience, Paul proves that their lives as sons of God and heirs of Abraham are by way of faith, not works of the law. Paul goes on to stress that this faith is the means of acceptance for all (v. 28). Therefore, once again, the Judaizing Christians have got it wrong. Nationalistic restrictions are done away with for those who know that acceptance by God is through faith.

Paul’s argument in this passage is fairly straightforward. After a statement of his point that all can be sons and heirs by faith (vv. 26–29), he gives an analogy (4:1–2) and applies that analogy to the Galatians (vv. 3–7). Because Paul’s most important points are scored in 3:26–29, the commentary section will focus on those verses.

Thesis Stated (3:26–29)

PAUL’S MAIN THESIS is that the Galatians are sons of God and heirs by faith in Christ (v. 26). He then restates his point by saying that all who were baptized have put on Christ (v. 27). That Paul was most concerned with the word all in both verses 26 and 27 becomes obvious by his explanation in verse 28: in Christ there are no racial, social, or sexual distinctions, because all are one. The implication of the “allness” of verses 26–28 is brought out in verse 29: those who belong to Christ are both the seed of Abraham and heirs.

Statement of sonship (v. 26) Paul’s beginning with “You” is sudden and somewhat unexpected, since he has been focusing on Jewish Christians and their experience of moving from “under the law” to “life in the Spirit.” However, that Paul ultimately has in mind not just a new Judaism (i.e., a Jewish church) is clear from how he moves freely from one group to the larger group (the universal church), and sometimes without giving notice. In fact, in 4:1–7 the focus is blurred, so much that at times we are unable to know which group is in focus (cf. 4:6).

The use of “sons of God” is important for the Galatians’ experience, for they learned to say “Abba” to God through conversion (4:6). Earlier, Paul had expressed that those who believe are “children of Abraham” (3:7), but now he points out that they are “sons of God.” In Galatians, Paul uses such terminology only at 4:6–7, and it may well be that the analogy to a son in verses 1–2 has prompted Paul’s use of the term here. Being a “son of God” is a special promise by God for the last days and describes that special relationship of intimacy that the people of God can have with God (cf. 2 Cor. 6:18). As Paul describes those who are “sons,” we should not pick up “manly” or “male” traits. Rather, in Paul’s letters “son” is especially related to both Jews and Gentiles (Rom. 9:26) who have been set free from the law (Gal. 4:1–7), who now live by faith in Christ (3:7, 26) and in the Spirit of God’s glorious freedom (cf. Rom. 8:14), and who await God’s final redemption (Rom. 8:19). The last thing on Paul’s mind when he used the term son was “manliness.”

We are closer to Paul’s intention if we find his emphasis on the word all, since this is the first word of the sentence in Greek (see 3:8, 22, 26, 28; 6:10). This is the word the Judaizing missionaries would have heard as particularly jarring. Their cause was to get these “half-converts” to become “full converts” by persuading them to adopt the code of Moses as the completion of God’s instruction. Now Paul tells them that “all” become sons of God through faith. The “allness” of God’s plan, the universalism, was predicted long ago (v. 8) and, while that plan awaited its fulfillment in Christ, the law confined “all” (v. 20). When Christ came and people believed in him, “all” became “one,” thus ending the national restrictions that governed Jewish behavior (v. 28). As a result of being part of God’s people, Christians are to do good to “all” (6:10).

Restatement of sonship (v. 27) As Paul restates his thesis of sonship, he makes several parallel comments, as this chart shows.

Sons of God | through faith | in Christ Jesus |

United with Christ | in baptism | |

Put on Christ |

What is important for our analysis of verse 27 is to realize that Paul sees faith as being expressed originally in “baptism” and becoming “sons” as the baptismal experience of being “united with Christ” and “putting on Christ.” Paul is probably thinking that, since Christ is the Son of God, being united with him and putting him on is what sonship is all about.

Some will no doubt have problems with the observation that faith and baptism are parallel expressions for Paul. Among many free churches in the world, baptism has taken on a secondary importance and is too often confined to “nothing more than an entrance rite” into the church. While it is clear that Paul makes a fundamental difference between external rites and internal reality (cf. Rom. 2:25–29; Phil. 3:3; Col. 2:11; cf. Gal. 5:6), and can even suggest that baptizing was not his purpose (1 Cor. 1:13–17), baptism was in the early church the initial and necessary response of faith. To be sure, their world was more ritual-oriented than ours and consequently got more out of rituals than we probably do.1 Nonetheless, we dare not make baptism “nothing more than a ritual of entrance,” for it was for the earliest Christians their first moment of faith, and we know of no such thing as an “unbaptized believer.”2 Baptism was not necessary for salvation, but faith without baptism was not faith for the early church. The Galatians knew this, and so Paul appealed to their experience.

The early baptismal ceremony was, in effect, a dying with Christ and a rising with Christ (so Rom. 6:1–14). This was its symbolic virtue: it dramatized salvation. Furthermore, the ceremony was frequently associated with two moral ideas: the putting away of sin and the putting on of a new life (cf. Rom. 13:12, 14; Eph. 4:24; 6:11–17; Col. 3:5–17).3 To be “clothed with Christ” perhaps refers to the early Christian practice of stripping and then reclothing oneself in a white, liturgical robe after the baptismal ceremony, thus symbolizing disrobing oneself of sin and then putting on the virtues of Christ.4

One more connection needs to be observed. As noted above, “sons of God” in verse 26 parallels the expressions “united with Christ” and “have been clothed with Christ” in verse 27. I would also suggest that the baptism of the Galatians (v. 27) was the moment in which they learned to call God “Abba” (cf. 4:6–7) and so, in effect, learned that they were all “sons of God” (3:26). Paul is now ready to make his point: the Judaizers are wrong because they do not realize that at their baptism the Galatian converts learned that they were sons of God.

The explanation (v. 28) Before drawing his conclusion, Paul pauses to explain what he means by “all” in verses 26–27. Here he sets out his cultural, social, and sexual mandates. These are set out “in Christ Jesus,” and we must first look at this expression.

What does it mean to be “in Christ Jesus”? In Galatians this idea is expressed in various ways: “in Christ” (1:22; 2:17), “in Christ Jesus” (2:4; 3:14, 26; 5:6), and “in the Lord” (5:10). Sometimes the “in Christ” expression means nothing more than “by Christ” (2:17; 3:14; 5:10), and once it conveys the special relationship a group of local churches has to Christ (1:22). The other instances signify the “location of believers”: they are “in Christ” (2:4; 3:26, 28; 5:6). This usage is sometimes called the “mystical ‘in’ ” in Paul. If what we mean by mystical is not just, or even primarily, ecstatic, this term is appropriate, for Christians have been swallowed up into Christ so that they live in him and out of a relationship to him. To be “in Christ” is to be in spiritual fellowship with him through God’s Spirit. This is one way of defining what a Christian is: one who is “in Christ.” While the ideas are not identical, to be “justified” is a different way of speaking of the same reality that takes place in being “in Christ.” Both expressions indicate the new relationship to God that Jesus Christ brings through the Spirit.

Those who are “in Christ Jesus” are those who believe in him; those who believe in him come from all walks of life, from every nation, and from both sexes. The problem the Judaizers had with Paul was that he did not properly (in their view) construct the church because he was breaking down the line between Jews and Gentiles. No doubt, they argued that this line was made by God when he called Abraham (Gen. 12). Paul now shows that faith in Christ obliterates such distinctions, and so he sees in the seed of the gospel a tree that has within it three mandates: a cultural one, a social one, and a sexual one.5 Thus, Paul goes beyond the concerns at Galatia by expressing what may have been an early Christian slogan that he endorses here and elsewhere (cf. Rom. 10:12; 1 Cor. 7:17–28; 12:12–13; Eph. 2:11–22; Col. 3:5–11).6 The revolution of Paul begins through Christ’s work and participation in him through faith.

Scholars have often observed that a Jewish blessing that was prayed daily by some Jews is reversed here: “Blessed be God that he did not make me a Gentile; blessed be God that he did not make me ignorant [or a slave]; blessed be God that he did not make me a woman” (Tosefta Berakoth 7:18). This is possibly a first-century prayer; the distinctions behind it were certainly made at times by Jews and by others.7 In any case, Paul is surely responding to such a demeaning classification of humans.

The cultural mandate:8 “neither Jew nor Greek.” We have addressed this mandate over and over. Paul set his face against anything that demanded a cultural and national conversion to become a Christian; no one had to become a Jew to become a Christian. This feeling of national distinctiveness on the part of the Jews was broken by the blood of Christ (cf. Eph. 2:13), which effectively annulled the curse of the law and its regime (Gal. 3:10–14; Eph. 2:14–15). The new era brought with it (and in its mighty wake) a cultural revolution. Cultural divisions are to have no part in the church of Jesus Christ. All humans must be treated in light of God’s love in Christ, not in light of their cultural past.

It goes without saying that the road to the elimination of such divisions for the first Christians was rocky and full of pitfalls. Paul describes one example in Galatians 2:11–14, and the Judaizers were seeking to fight against this essential point of the gospel. Peter had troubles elsewhere (Acts 10:1–11:18), but eventually the church of Jerusalem was willing to say that “God has granted even [note this term!] the Gentiles repentance unto life” (Acts 11:18).

The social mandate:9 “neither slave nor free.” Slavery was widespread in the ancient world among Gentiles and Jews. It was generally different from, though it included, the mistreatment of racially different slaves as evidenced in the United States in the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. For the ancient Roman world there have been estimates that slaves comprised as much as thirty-three percent of the population. Slaves were gained in numerous ways: purchase, indebtedness, capture in war, and birth. Regardless, the number who were treated fairly and kindly appears to be an exception rather than the rule. The Old Testament developed rules of kindness to slaves (cf. Lev. 25:39–55).

Our social mandate in Galatians can be taken in two ways: as a social statement for the abolition of slavery as an institution or as a declaration of the irrelevancy of the institution in Christ. In light of 1 Corinthians 7:21–24 and Philemon, it seems best to see Paul giving a declaration of the second option: the irrelevancy of one’s social status for acceptance with God and life in the church. As with culture or race, so with social status: there are distinctions but they are irrelevant. Nonetheless, the social mandate explodes with social possibilities. “In Christ,” Paul says, the slave becomes our “brother” (Philem. 16). Both freedmen and slaves have the Spirit and are in the body of Christ (1 Cor. 7:21–24). In fact, it is indeed likely that in the early church slaves were leaders, and their owners submitted to them in the context of the church.10 As R. N. Longenecker observes: “The phrase is also pregnant with societal implications. And undoubtedly some early Christians realized, at least to some extent, the importance for society of what they were confessing.”11

While Paul did not set up here a social agenda, he created an atmosphere that would eventually lead to the abolition of slavery throughout the whole world. In the history of the church, various movements (among the later movements we name the Quakers) sought to implement the abolition of slavery completely. With the rising tide of the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s in the United States, the entire issue took on new significance for the church. While progress has been slow, much slower than it should be in the church, there has been progress. We can only pray for further courage to live our lives in a way that is consistent with the “irrelevance” of slavery in Christ. Social classes ought to have no bearing on the church’s work.

The sexual mandate:12 “neither male nor female.”13 For some reason, the sexual mandate has been even more explosive than the cultural and social ones. Again, we need to observe that Paul spoke these words in a given historical and social context, a context that clearly believed in the inferiority of women. Whether we quote texts from the Greco-Roman world (Galatian context) or from the Jewish world (the context of Paul especially and of some Galatians), there was a widespread conviction that women were inferior. The Jewish historian Josephus wrote, for example: “The woman, says the law, is in all things inferior to the man” (Against Apion, 2.201). Paul’s agenda in verse 28 assumes this context. Why else would he point to “neither male nor female” as his third pair of things that have been abolished in Christ?

This principle of inferiority worked itself out in many ways. I mention but a few. Women were talked about in rude and condescending ways; they were not to be taught the law; they were to tend to their children; they were not considered reliable witnesses in court; they may have even sat in seats separate from men in synagogues. One could paint even a grimmer picture if one desired. I have not because I am also aware that women were at times given positions of leadership (for example, Phoebe in Rom. 16:1–2) and, in actual practice, I suspect that women were given more respect than the surviving literature suggests (see the story of Priscilla in Acts 18).14 But positive ideas are not behind Paul’s desire to see “sinful” walls broken down.

So it was inferiority of women working itself out in religious communities that Paul opposes with this statement “neither male nor female.” In the same way that there was to be no cultural/racial distinctions and no social status prejudices, there was to be no sexual prejudice. For those who are in Christ, antagonisms, criticisms, snide remarks, subtle insinuations, and overt prejudices must end, for in him male and female are one. I believe that, as is the case with slavery, so with women, Paul provides an agenda that would take years for the church and society to implement properly and honorably before God.

The implication (v. 29) Paul concludes with an implication of being a son of God. Since the Galatian believers are “in Christ” and since Christ is the Seed of Abraham (v. 19), then it follows that the Galatian believers are also Abraham’s seed. And if they are Abraham’s seed, then they also inherit Abraham’s promise—a relationship with God that entails his blessing and goodness. So Paul concludes that the Judaizers are wrong because of the intrinsic connections he spells out: Abraham-faith-Christ-seed of Abraham by faith: both Jews and Gentiles. What the Judaizers wanted was the promise of Abraham, but they thought they had to follow the law of Moses in order to get it; Paul, however, knew that one received the Abrahamic promise by faith. That the Galatian believers knew that God was their father was sufficient proof for Paul.

The Analogy and Its Application (4:1–7)

PAUL’S THESIS, WHICH we have treated in a more thorough fashion than usual, is now illustrated with an analogy and then applied. Until Paul says “What I am saying is … ,” we may not have been able to understand his logic. But now we see that in 3:26–29, Paul has set up his basic point that sonship demonstrates that the Judaizers are wrong. These next two verses (4:1–2) show us how he makes the point. A child who is destined to inherit an estate is no different than a slave as long as he is a child (until twenty to twenty-five years old), for he cannot inherit that estate until he becomes an adult. During this period he is subject to the “guardians and trustees,” but only until the father’s set time of inheritance.

In verses 3–7 Paul applies this analogy to make a point about Israel’s history that is almost identical to the point made in 3:15–25: namely, the “childhood period” is the period of the law and the “inheritance period” is the time inaugurated by Jesus Christ. Full rights (i.e., freedom from the law) do not come until after Christ’s work is done. The time of the law is a time of slavery; the time of Christ is a time of freedom. What Paul does not say, but what he implies, is that the time of slavery was a time of “works of the law” and the time of Christ is the time of “faith.”

First application: we were enslaved (v. 3) “When we were children” is Paul’s description of Jewish life under the law (and perhaps Gentile life under the “law written in their hearts”). But Paul says they were enslaved “by the basic principles of the world.” What does this expression mean?

The only other place Paul uses this term15 in Galatians is 4:9, where he is describing a return to either pagan life with its tribal/national religions (cf. v. 8) or to the Mosaic laws regarding “special days and months and seasons and years.” We can gain more insight into the meaning of this expression by comparing “basic principles” to the negative dimensions of the previous era as described in 3:15–25. Here it must refer to the law that came after the promise (vv. 15–18), to its sin-revealing purpose (v. 19), to its temporal limitations (v. 19), to its inferior status because of its need for mediation (vv. 19–20), to its inability to bring life (v. 21), and to its imprisoning function (vv. 22–25). Thus, it is best to see “basic principles” as a reference to the law in its negative and suspended features.

Once again, the Judaizers would have been offended at Paul’s rather disparaging view of the law. How can Paul, we imagine they might have asked, say the law was nothing but the “ABCs” of God’s revelation? I believe Paul has worked this out quite carefully: it is because he sees Jesus Christ as the climactic fulfillment of the Mosaic revelation. To revert to my typewriter illustration, the former era is nothing but a time when Jews hammered out their ABCs on a typewriter; the new era is a fulfillment of that machine and an entirely new agenda is in order: not just ABCs, but sentences, paragraphs, chapters, and books are now in order! That old typewriter (the law) is a “basic principle” compared to the fullness of the computer age (Jesus Christ and God’s Spirit)!

Second application: we were made sons (vv. 4–5) As with the time set by the father for the maturation and inheritance for his son, so also with God. When the “time had fully come,” God sent his Son so that the inheritance could be had. The expression “fully come” is the completion of the “basic principles” of verse 3. God sent his Son, and this Son lived under the law (though not under sin) so that he could absorb the curse of the law, exhaust the fumes of God’s wrath, and redeem those under the law. Once the Son had done this, the barrier was knocked down between God and people (and between peoples), and they could become “sons of God” (v. 5). Their sonship is tantamount to governing the “whole estate” (v. 1), as Paul will show.

Third application: we are heirs (vv. 6–7) Being a “son of God” means having God’s Spirit, which is the promise of Abraham (3:14); this is what the Judaizers want too. The Spirit of God enables the son of God to cry out “Abba.” “Abba” is the Aramaic term for “father” and became the special language of Jesus for addressing God (Matt. 6:9–13; Mark 14:36).16 Jesus’ prayer language was followed by the early church; thus, the early Christians saw addressing God as “Abba” as their distinctive mark. It marked them off, as circumcision marked off male Jews, in a way that made them realize they were the “sons of God.”

If, therefore, the Galatian Christians are calling God “Abba,” they are “sons of God”; the ability to call God “Abba” is evidence of being a son of God. This means they are no longer “slaves,” living in the old era (typing on a manual typewriter). And since they are sons, they have the inheritance.

We can now fill in Paul’s logic: since believers have the inheritance by faith, they do not need to live out the “works of the law”; therefore the Judaizers are wrong in urging what amounts to a nationalistic view of God’s work, and it need not be followed.

Bridging Contexts

ONCE AGAIN, WE have arrived on the same shore: acceptance with God is based on faith in Christ and not on observing the law. Everyone who believes, whether Jew or Gentile, slave or free, male or female, is accepted by God. On the contrary, the Judaizers have duped the Galatian converts into thinking that they needed to convert “all the way to Judaism,” that is, to a particular nation, in order to be fully acceptable to God. But Paul stands firm with the grace of God, through Christ, in the Spirit, by faith—for all. This has been his message from the beginning. But Paul has gotten to the shore this time on a different boat: the boat of sonship. He has explored the theme of sonship, and the experience of sonship that the Galatians knew all about, to argue his case.

How do we apply this theme of sonship to our context? Ours is a day that has been deeply influenced by what is often described as “women’s liberation.” I am completely for the “liberation of women” and for the liberation of everyone and everything—as long as “liberation” means “slavery to Christ” (Gal. 1:10; cf. Rom. 12:11; 14:18) and to one another in love (Gal. 5:13). We as Christians need to sympathize with the plight of women in the history of the civilized world and to understand the impact that some awful institutions have made on how they have become what they are. Indeed, feminists have accused the teaching of the Bible, and Paul is not exempted here, of both fostering and establishing the oppression of women. While feminist interpreters of Scripture praise the “insight” of Paul here in 3:28, they also point out that neither Paul himself (see 1 Cor. 14:34–35; Eph. 5:22–33; 1 Tim. 2:8–15) nor other New Testament writers grasped the implication of this call to liberation here. They argue that as the church took a long time to grasp the equality of races (and so ended slavery), so it is taking too long to do the same for women: liberate them from the bondage of male dominance and from a patriarchal world.

Why bring this up? Because these same critics of the biblical message contend that calling God’s children “sons” is also patriarchal, condescending, and expressive of a male-dominated worldview. They say that they do not want to be called “sons” since they are not males; they want to be called “daughters.” God, they argue, is not a “male”; thus, they urge sensitive people to abandon “chauvinistic language” that was used by God accommodatingly in the Bible and translate such expressions with “sexless” terms, like “children.” This is exactly what the NIV had done at 3:7. What should we do?

I wish to make two points, the first about translation and the second about sensitivity. In our final section I shall try to “update” the message of Paul about sonship for our world. First, the matter of translation. What is an acceptable translation of the word huios (“son”), which refers to a male child? This word does not refer to a girl, and it is different than the term “child” (which largely describes the developmental stage of a person). Furthermore, there was something in the reference to a son that would not have been conveyed in the term “child” or “daughter,” namely, the privileges inherent to becoming a man and inheriting a father’s estate (in a patriarchal world). Thus, in preferring the term “child” (as the NIV does at 3:7) something is lost. Is it best to lose something so as not to be offensive? I think not, at least not in this case. There comes a point when translation is no longer translation; it becomes “updating” or “paraphrasing” or “contextualizing.”

I am all for each of these maneuvers in our interpretation and in our application; I am not, however, for the translation of any text that would harm the original message. No matter how important it is for us to make the gospel relevant, there comes a point when we must not tamper with the message so as to make it relevant. I believe this applies to the matter of sonship in Galatians. While I am deeply disturbed by patriarchy and chauvinism, I do not believe that the way to eradicate them from society is to retranslate ancient texts so as to give the impression that they never existed. Instead, I would prefer to see “footnotes” or special devices (e.g., using all caps to make one sensitive to the issue: SONS OF GOD is “non-sexist” in implication) in popular translations, especially pew Bibles, that call attention to issues that press against the church today.

Second, the matter of sensitivity. Having said that I prefer not to retranslate the whole Bible so as to avoid all traces of patriarchy, I am also of the view that it is fundamentally important for Christians to be sensitive and to be as “nonsexist” in their language as possible (with the above proviso). Not only should we be sensitive; we need also to change structures so that oppression of women is eliminated, just as we have been actively against cultural and racial biases.

So to move into our world with the message of Paul about sonship means, first of all, to cut through the rhetoric of patriarchy and male dominance while at the same time respecting what translation actually is. Then we need to find out just what “sonship” and “inheritance” meant for the Jewish world (and the Galatian context), so that we may have a firm grasp of what Paul meant. To repeat what was said in the “Original Meaning” notes, the term son does not necessarily mean something about “manliness” in the sense of “macho.” Here many interpreters (and some feminists) go astray: they begin with what “son” means today, or what it means in their reconstructed patriarchal world, and then proceed to show just how chauvinistic the text can be.

Without getting into the obvious patriarchy of the ancient world, I still contend that the way to do a study of a word and its associates is not by looking at what “son” means in our world or even what “son” can mean in a patriarchal world. What we need to do is to see how Paul uses the term son and then trace the connections and connotations he provides for his readers. These are the ideas we will want to focus on. I am convinced that for Paul “son” does not have the senses that many feminists think it has. To be sure, it comes from a patriarchal world in which men were superior to women and sons superior to daughters. But, and here is my point, the assumptions aside, Paul does not exploit these features of the meaning but other less patriarchal and more positive ideas.

Sonship denoted for Paul the special intimacy that God’s people can have with him, the freedom those people experience from the bondage and curse of the law, as well as the filling of the Spirit that God enables. In addition, the theme of sonship also speaks to the hopeful stance of the believer as he (or she!) awaits the fullness of salvation that comes when brother time gives birth to sister eternity. These are the ideas that need to be explored as we think about our sonship in Christ. As we apply the message of sonship, we need to be both historically accurate and pastorally sensitive, expressing a very real patriarchal idea in a way that does not offend our sensitivities and that focuses on those features that are significant to the author.

A second feature of our text that strikes the reader is the emphasis on “all,” the theme of universalism, in the “thesis” section of his argument (3:26–29). Nowhere else in Galatians does Paul spell out the vastness of the love of God for all. He says you are “all” sons of God (v. 26), for “all” of you were united with Christ (v. 27), and “there is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (v. 28, italics added). Regardless of who you are, if you believe, you get to inherit the Abrahamic promises (v. 29).

How do we move this message of universalism into our world? We have already applied the universalism of Paul to our day in the areas of racism (the social mandate of v. 28) and denominationalism (the social and cultural mandate of v. 28). One area we have not explored is how the universalism of Paul applies to the sexual mandate of verse 28: “neither male nor female.” We will therefore explore this here.

I have seen several ways people have sought to “apply” New Testament texts about women in our world.17 The first we call the “condemn and dismiss” approach. What takes place here is the conclusion that the New Testament evidence is almost exclusively chauvinistic (most, however, exclude v. 28 by claiming more than it actually teaches) and therefore to be condemned as a product of its time. It must thus be dismissed after we have learned the lessons it has taught us about oppression. Most readers will see in this view one that can hardly maintain a firm grasp of evangelical theology, and so most evangelicals have dismissed the view itself.

A second approach I shall call the mutual equality but functional subordination view. This is the traditional view, espoused throughout the history of the church. For those who hold this view, the New Testament teaches both equality before God in status (v. 28) and functional subordination in office (e.g., 1 Tim. 2:11–15). Thus, these proponents see two strands in the New Testament they think can be woven together by positing that, while God accepts women in the same way he accepts men (by faith in Christ), that acceptance does not revolutionize social differentiation and differing roles for the sexes. It follows that the roles for women in the church are almost always seriously lessened by this view.

A third view may be called evangelical and feminine liberation. While this view wants to submit to Scripture (as is not seen in the first approach to these texts), it also recognizes the cultural conditioning of the text of the New Testament and seeks to eliminate it as we move the truth of God into our modern world. Furthermore, under this approach is a recognition that our society is considerably different than Paul’s.

How should we proceed? Let me suggest a model that we can use that may be compatible, at the outset, with both the second and third approaches. To begin with, we must do our homework on the ancient world (what were the lives of women like around the Mediterranean Sea?) and on the New Testament texts themselves. We must understand what the text meant in that world before we can have any hope of moving it into our world. Much work has gone on in this area in the last few decades.18 The foundation for this series of commentaries is that the ancient world is not identical to ours and that to apply the ancient text to our world requires patient historical work so we can discern what the text meant.

Another part of this step is a very careful examination of what Paul says about women. More frequently than not, readers of the Bible and professional interpreters (who should at least know better) decide that one text is superior to another; thus, they make one set of texts fit into their descriptions of another set of texts. On this particular issue, some take Galatians 3:28 as the most important truth of Paul about women, make texts like 1 Corinthians 14:34–35 and 1 Timothy 2:11–15 fit into that text, and end up making Paul the first feminist. Others operate in the opposite direction and end up squeezing all the juice out of Galatians 3:28 to the point that it says absolutely nothing new (God loves all people). The only legitimate way to do serious biblical theology is to believe all the texts and fit them into some reasonable whole. As for verse 28, if we are going to examine Paul’s view of women properly, we must say that for Paul “equality in Christ” is not necessarily “elimination of distinctions of roles” for his time.

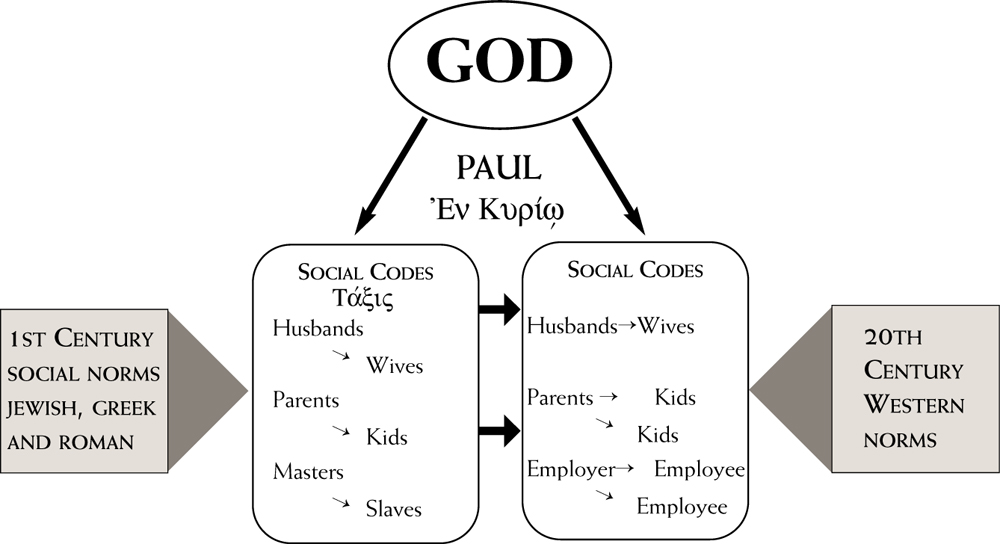

Second, as a result of this historical work, we must compare that social world to our social world and, in particular, compare the role women had in the ancient world to the role they have in our world—and the modern world differs considerably. To do this we need to read books on our culture and on women in our culture.19 With a good picture of both worlds, we need to compare them, see how Paul’s teaching “fits” into our world (or how it does not “fit”), and then start to work with the business of applying. We quickly discover that women’s roles were different in that world from what they are today. We learn that the New Testament, and Paul, were influenced by such things as the prevailing social norms (many say this is what Paul is talking about in 1 Cor 11:2–16) of the Jewish, Greek, and Roman worlds, which came to them as self-evident truths and conventions. Today we think it is wrong (in most of the Western world) for men to wear dresses, but men in Africa wear outfits that are entirely feminine when looked at from our viewpoint. We think these things are rights and wrongs, even though they are social conventions, rules we play by. This order of Paul’s society was seen as under God’s providential arrangement, and we see the same in our world. What we need to do is to compare social norms, see how Paul’s statements fit into those social norms, and then make applications.

The third step is to recognize that development takes place over the centuries in social structures. The social structures of the first century were not any more God-ordained than the ones in our age. It may be that at times ours are better, but may it be that at times theirs were better? Along with the development that has occurred over centuries comes change, and along with change comes the necessity of interpreting and applying for a different world.

One example will suffice to make our point about change. I know of only one or two small denominations that believe in foot washing and, unless the rest of Christendom is wrong and they are right, I do not see God refusing to bless his people because they are not washing one another’s feet. Jesus, of course, commanded this practice (John 13:12–17), and evidently it was practiced in the early church (1 Tim 5:10; Augustine, Letters 119.18). In spite of Jesus’ direct words and the early church’s testimony to obedience to his words, Christians of all ages and places have no problems dismissing it as a custom of an ancient world that can be accomplished in other ways today. In particular, I was taught that hospitable reception of a person is an equivalent. So we were taught to stand when others enter our home, greet them, and do whatever was necessary to make them comfortable (take their coat and hat, get them some tea, etc.). I think this is correct. But the process of interpretation is one in which we explicitly eliminate a command of Jesus and substitute in its place a cultural equivalent.

“Cultural equivalent” is the key here. Other examples might come from our permission for women to wear jewelry (just go to church on Sunday!), even though Peter prohibited it (1 Pet. 3:3–6), and our complete disregard of Paul’s comments on the theological grounding of short hair for men and long hair for women (1 Cor. 11:2–16). I suggest that applying texts on women involves a similar process: serious biblical and sociological study of women in the ancient world, the Pauline letters, and our world; careful comparison of the roles of women in both worlds; identification of change and development; and finding cultural equivalents.

Speaking of development and change leads to yet another idea: the idea of progressively working out what Paul says. I know of few people who think slavery is right. But Paul evidently did not think it was completely wrong; thus he encouraged slaves to remain as slaves and commanded masters to treat their slaves kindly. He certainly did not think the gospel brought a social revolution by way of abolishing slavery. And yet, for moderns, slavery is wrong. Most Christian interpreters think the Bible taught a kinder view of slaves than the ancient world (which is surely generally true) and that Paul’s statement in verse 28 provided the statement that would eventually lead to the abolition of slavery. For these interpreters there is a progressive unfolding of the actual working out of God’s will, with only part of that progression caught in the Bible. Perhaps it is the case that what Paul said in verse 28 about women will unfold in history in the same way as the slavery statement has. Perhaps as humans have been freed from the awful grasp of ownership by other humans, so also women will be freed from their bondage to social inferiority.

I believe these are the steps we need to use before we can talk about women in the church, before we have truly and responsibly applied Paul’s statement in Galatians 3:28 to our world. What we will see is that the cultural conditioning of the ancient world led Paul to apply his view of the equality of women with men in certain ways that did not harm the preaching of the gospel (hence his restrictions at 1 Cor. 11:2–16 and 1 Tim. 2:11–15). But when those cultural conditions changed, his applications would have changed; and so I am of the view that the statement of verse 28 is fundamental to Paul’s entire approach and that it should be to ours as well.

In this section we have looked at two issues: sonship and the equality of women according to Galatians 3:28. In our next section, I will look at sonship and seek applications for Paul’s teaching in our world. The above discussion on women will suffice for our purposes—because of space constraints and because the discussion above on women points us in the directions we need for applications. After all, the passage we are considering is about sonship.

Contemporary Significance

WE BEGIN WITH a new view of sonship. To make this message relevant to our world we need, as I said above, to be sensitive to sexist language. So my proposal is that, while we retain the term “son,” we make it non-sexual. To be a “son” of God does not mean to be “manly” or “masculine.” It means:

Being intimate with God. In our world, being a “son of God” is not similar to being “intimate with God.” But according to Paul, a “son of God” is one who learns to call God Abba because God has given his Spirit to his sons. Calling God Abba is the most intimate language of the family in the Jewish world. This was the first term a Jewish child learned (along with imma, “mommy”), and it can be translated “daddy.” While “daddy” is accurate, there is more to it than the language of a child. The father, the abba, in Judaism was also a commanding authority figure for the Jewish family, and children were taught never to disagree with and always to honor him. Thus, the term abba is not just the prattling of a child, not just the language of little children with their loving fathers playing games and talking sweet things; rather, it is the term that Jews used for their relationship to their fathers that involved both relational intimacy and honorable respect.

A “son of God” is one who relates to God both with love and with respect. We develop intimacy with God through prayer—prayer that explores God’s relationship to us and our relationship to God, prayer that is trusting and vulnerable to God’s promise and sure word, and prayer that is designed to live before God obediently and lovingly. We develop intimacy with God through a lifestyle that remains in consistent conversation with God as each day progresses. Instead of diddling our time away with thoughts of fleeting things as we drive the car or wash the dishes or go for walks, we can spend our time in those activities talking to God and listening to him speak to us as his children. We can pray and learn to know God.

We also develop intimacy with God by reading his Word, believing it, obeying it, and sharing it with others. But mostly, we learn to be intimate with God by trusting in him and learning through that trust that he is loving and good. God desires that we desire him. In that desire he is delighted, and we become delighted in his delight. Loving God’s delight is what intimacy is all about, and that is what it means to be a son of God.

Being free from the curse of the law. To be a son of God means that we (both Jews and Gentiles) have been set free from the curse of the law, that we have moved from the B.C. era to the A.D. era (shall I mention typewriters and computers again?!), and that we have left the age of tutors and guardians to being led by God’s Spirit. I believe analogies help here.

As parents we tag along with our children when they are young because we know they are too irresponsible to make good decisions. Parents, of course, differ on when they start letting children make their own decisions, but I am not talking about tagging along with our children when they go to college, get married, and start their careers. When our kids are young, we help them up the steps on a slide so they do not fall off; we accompany them to the bus stop so they do not venture onto the street; we accompany them to sporting games so they are not taken advantage of; we look after their homework so they get it done on time; we drive with them (as we recently did with our daughter Laura) so they will learn to drive responsibly and not peer out the window for their friends; and on and on. Children must get tired of being looked after, and it must feel good when they get to school (away from their parents), when they get to summer camps, when they go to college, and when they finally leave home and set up their own establishment. That feeling of relief from “being looked after” and “constantly corrected” is similar to what Paul meant by being a “son of God.” A “son of God” is one who has been set free from tutelage and turned loose with God’s Spirit to guide them.

No longer suffering the guilt of being a sinner before God, no longer fearing the awful wrath of God, and no longer being sentenced by God as cursed—that is what it means to be a “son of God.” Anyone who senses his forgivenness before God, anyone who knows he (or she!) has been welcomed into God’s big family, anyone who knows that the law cannot condemn them because Christ has absorbed the law’s curse, is a “son of God.” We are sons of God solely because Christ, the Son of God, has made us part of his family by dying on our behalf.

Being led by God’s Spirit. Because we have become sons of God, God sent his Spirit into our hearts. I doubt very much whether we can know the order in which these things happen: rather, conversion is a complex event in which God works and we respond, and because God works and we respond, certain good things happen to us. These good things can be defined in a host of ways. Paul, for one, raided the ancient vocabulary to describe what took place—he used terms like salvation, justification, reconciliation, and propitiation (strange terms for us). But essentially what took place was that God “took us back” and “accepted us” (terms that make more sense to us).

The great gift God gave to us because we are his sons is the gift of the Spirit. Paul says that anyone who is a Son is “led by the Spirit” (Rom. 8:14). While Paul does not connect “sonship” with being “led by the Spirit” in Galatians, he certainly thinks they are connected because he sees Christians as sons (Gal. 3:26–4:7), and he sees Christians as those who are “under the Spirit” (5:16–26). A son of God, then, is one who is “led by God’s Spirit.”

Legalists are led by the law; hedonists are led by their desires; materialists are led by their possessions. But sons of God, Christians, are led by the Spirit. What prompts their actions, what stirs their emotions, what guides their behavior, and what determines their careers is God’s Spirit. Furthermore, sons of God do not fear and worry about where the Spirit will lead them. They know that God’s Spirit will lead them perfectly into God’s will and God’s blessing so they march behind confidently and joyously.

Are you a “son of God”? Are you intimate with God, are you free from the law’s awful curse, and are you led by God’s Spirit? You can become one by faith. “You are all sons of God through faith in Christ Jesus” (v. 26).