A play wherein one man now enters and another exits; with tears it begins and with weeping ends. Yea, after death itself, time with us still toys, when foul maggot and worm drill out putrid corpses …

This is a study of Reformation culture in the stage of capitalist transition. Literally the “stage”, since Benjamin’s model is the Baroque form of the Trauerspiel or mourning-play. The book’s dedication “Conceived 1916 – Written 1925” stresses the continuity between it and the 1916 fragments on the differences between classical tragedy and the mourning-play (see pages 33-37). The key to the mourning-play is to ask – what is being mourned? And why with such ostentation? Or as the playwright Daniel Caspers von Lohenstein (1635–83) puts it …

A play wherein one man now enters and another exits; with tears it begins and with weeping ends. Yea, after death itself, time with us still toys, when foul maggot and worm drill out putrid corpses …

These are plays for the satisfaction of the mournful which require Baroque excess.

The origin of the term baroque is uncertain. Some argue that it comes from “rough-shaped pearl”; others that it refers to “absurd”, “bizarre” or “extravagant”. Baroque differs slightly in its application to art and architecture, literature and music. This allegorical painting by Jacopo Tintoretto (1518–94), “The Origin of the Milky Way”, displays baroque features of “bizarre extravagance”.

The Baroque speaks in allegory.

This allegorical image of “milkiness” pairs nicely with another by the Baroque poet, Richard Crashaw (1612?—49), an English convert to Catholicism at the height of the Counter-Reformation. One stanza from his poem on St Mary Magdalene suffices to illustrate the bizarre spinning out of a “mournful” metaphor.

But what was in the Baroque climate that encouraged such extravagant allegory?

The essential doctrine of the Protestant Reformation laid down by Martin Luther (1483–1546) was that salvation depended on grace through faith alone, which denied any spiritual effect to human action. Life was devalued by faith and melancholy was the inevitable outcome. The mourning-play gives us the world revealed in the gaze of isolated melancholy man.

He is the onlooker – like hamlet – deprived of the community of significant human action. To be or not to be that is the question

Instead, the Catholic reaction to Protestantism in the Counter-Reformation reasserted the redemptive authority of the Church, gave power to the Jesuits and extended the Inquisition, but also revived Catholic spirituality in the secular realm.

Lohenstein, Andreas Gryphius (1616–64) and other German writers of the Baroque Trauerspiel were all Lutherans. Benjamin makes the point that Shakespeare and the Catholic Spaniard Calderon de la Barca (1600–81) created far more important mourning-plays than these largely forgotten German ones. There are nevertheless certain formal elements of the genre which they all share – beginning with the “world as the stage”, “a setting for mournful events”.

Draped in cloth, overfurnished with emblems, the earth-as-stage becomes a coffin.

If the stage is a coffin, it is also the world’s toy-box from which pantomime players emerge, typified by their roles: the evil intriguing courtier (lago); the absent or dreamer hero (Hamlet); the king, hybrid of tyrant and martyr, either usurping or usurped (Hamlet’s father); the parody commentators, clowns, fools and jesters.

Actions in the mourning-play do not add up. Speech and gesture mislead, decisions are postponed, and the end is nihilistic catastrophe: such as Hamlet’s “accidental” death by a poisoned rapier.

There is a special providence in the fall of a sparrow …

These playing-card figures appear to enact the Baroque circumstances of closed theologies, of emerging Divine Right monarchs and absolutist states, but in fact they mourn the off-stage transition to capitalist modernity. The world is drained of meaning and the only bleak Lutheran hope is that absurd meaninglessness can become the source of salvation.

Benjamin opens his study with a daunting “Epistemo-Critical Prologue” in which he tackles the problem of origin. Origin is described as “an eddy in the stream of becoming”, in other words, something that is both in and out of time. This peculiarity of origin – outside time but open to its effects – permits him to identify allegory as the key feature of Baroque culture.

Classical tragedy hinges on the symbol which presents a timeless truth in the beautiful appearance, even if imperfectly. Allegory instead presents the temporariness of truth in the ruination of appearance.

This is summed up in Benjamin’s famous aphorism.

“Allegories are in the realm of thoughts what ruins are in the realm of things.”

The mourning-play was conceived from the outset as a ruin. Now it becomes clear that Benjamin’s analysis of allegory in Baroque drama revealed to him the origin of modernity. The fragmented nature of modern experience – the way it is experienced discontinuously as shock – was “originally” manifested through Baroque allegories of ruination and transience.

The ruin is what we are left with, once the life that allegory has temporarily breathed into a form has fled

“All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses, his real conditions of life …” Karl Marx, Manifesto of the Communist Party, 1848

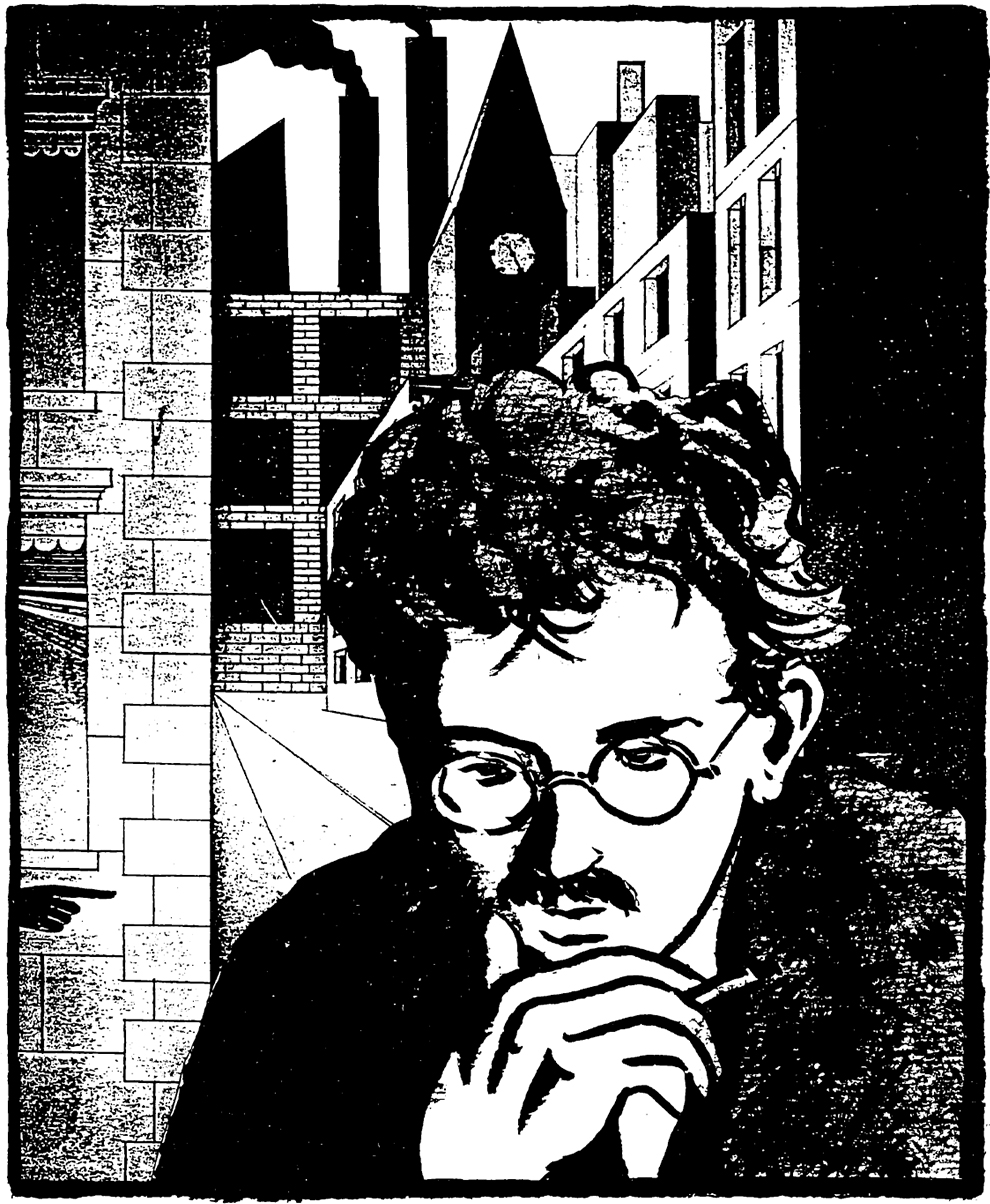

In 1925, Benjamin made one last desperate effort to gain the Habilitation (qualification for a university teaching post) and secure his financial independence. He submitted his Trauerspiel study as a qualifying thesis to Franz Schulz, professor of literary history at the University of Frankfurt. This proved another of Benjamin’s “large scale defeats”.

I advise you to try the aesthetics department … But the professor of aesthetics doesn’t understand it either!

And so, the Trauerspiel went round the various departments on a voyage of scandalous incomprehension, until Benjamin withdrew it. “Better to be chased off in disgrace than retreat.”

It was as if Benjamin had fallen victim to the intriguing courtiers in a Baroque academic pantomime. Once again, his Angelus Novus was grounded, indeed, stripped of its beauty.

My Poor angel may never fly until some future time … Here the flesh is decaying and the louse eating its way in. Pull off the rags! What is revealed? A decaying corpse …

Benjamin published The Origin of German Tragic Drama with Rowohlt in 1928.

Today, we still find a fragmented Benjamin circulating the university departments, in a different sense now, as each one tries to claim “their” piece of him. Benjamin perhaps foresaw this in a sly allegorical fairytale he wrote that was originally intended to preface The Origin of German Tragic Drama, but was dropped.

The academic débâcle may have hastened Benjamin’s involvement with Marxism. He turned to writing for a wider media-receptive public, exemplified by One-Way Street, also published in 1928. This short work, of fragmentary observations and lists, combines allegory with the style of the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit), a dominant art movement in late 1920s’ Germany. The new style reflected the increasing coldness of modern urban experience: a clinical refusal of emotion, a cynical presentation of the world “as it is”, and a cult of technology.

Warmth is ebbing from things. Expect no comfort from your fellow men …

Bus conductors, officials, workmen, salesmen – they all demonstrate the menace of the material world through their own surliness.

Benjamin foresees a “picture-writing of the future” in graphic stages.

1. writing begins gradually to lie down …

from upright inscriptions, to manuscripts on sloping desks and finally to bed in the printed book …

2. writing begins to rise up again …

newspapers are read in the vertical, film and advertisements dictate the perpendicular …

3. the book is outdated by the three-dimensionality of the card-index filing system …

4. a leap into future graphic regions: statistical and technical diagrams – an international moving script – and into the “ether” of the Internet …

Benjamin meditates in allegorical “new objective” style on the potential gains and perils of modern technology.

The dark night of war-time annihilation shook us like the aura of bliss that the epileptic experiences in seizure. The revolutions after it were mankind’s first attempts to bring this new body under control.

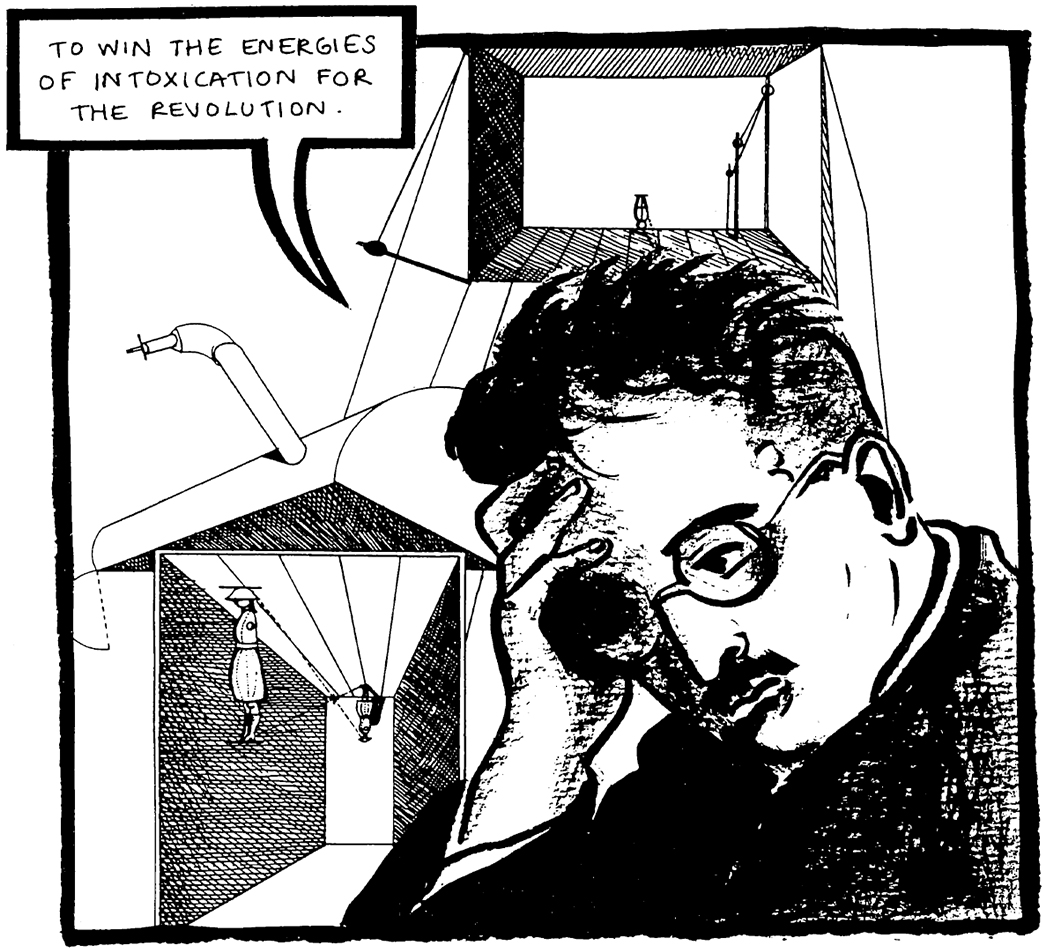

Benjamin’s writing has much in common with Surrealism’s “irruption of the Unconscious” in everyday life, a link not sufficiently appreciated. His essay, “Surrealism: the Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia” (1929), defines profane illumination as Surrealism’s true revolutionary aim, something that can begin with hashish or opium, but which is less dangerously effective than the “narcotic of thinking”. This could well describe Benjamin himself. And it is again with himself in mind that he names “the project around which Surrealism circles in all its books and enterprises”. What is this project?

To win the energies of intoxication for the revolution.

He scolds the Surrealists for their flirtations with the occult and spiritualism, but this could also be a self-criticism of the mysticism in his own nature. In fact, many Surrealists became Communists in the 1920s.

Benjamin’s friendships, like his life, seem dictated by coincidences, good and bad. He could have lamented, in Aristotle’s words, “O my friends, there is no friend.” Gershom Scholem, settled in Palestine in 1923, continued to advise and scold him as a “voice afar” from the sunny Promised Land. Two other friendships grew complex but also very productive in the 1930s: with Theodor (“Teddy”) Wiesengrund Adorno and Bertolt (“Bert”) Brecht, the polar opposites of contemporary Marxism.

Brecht is a vulgar materialist, a pet it-bourgeois poseur, and an apologist for stalinism! And what good is your bourgeois lifestyle and over-subtle intellectual marxism? We’re building a new jerusalem. Why don’t you come over here?

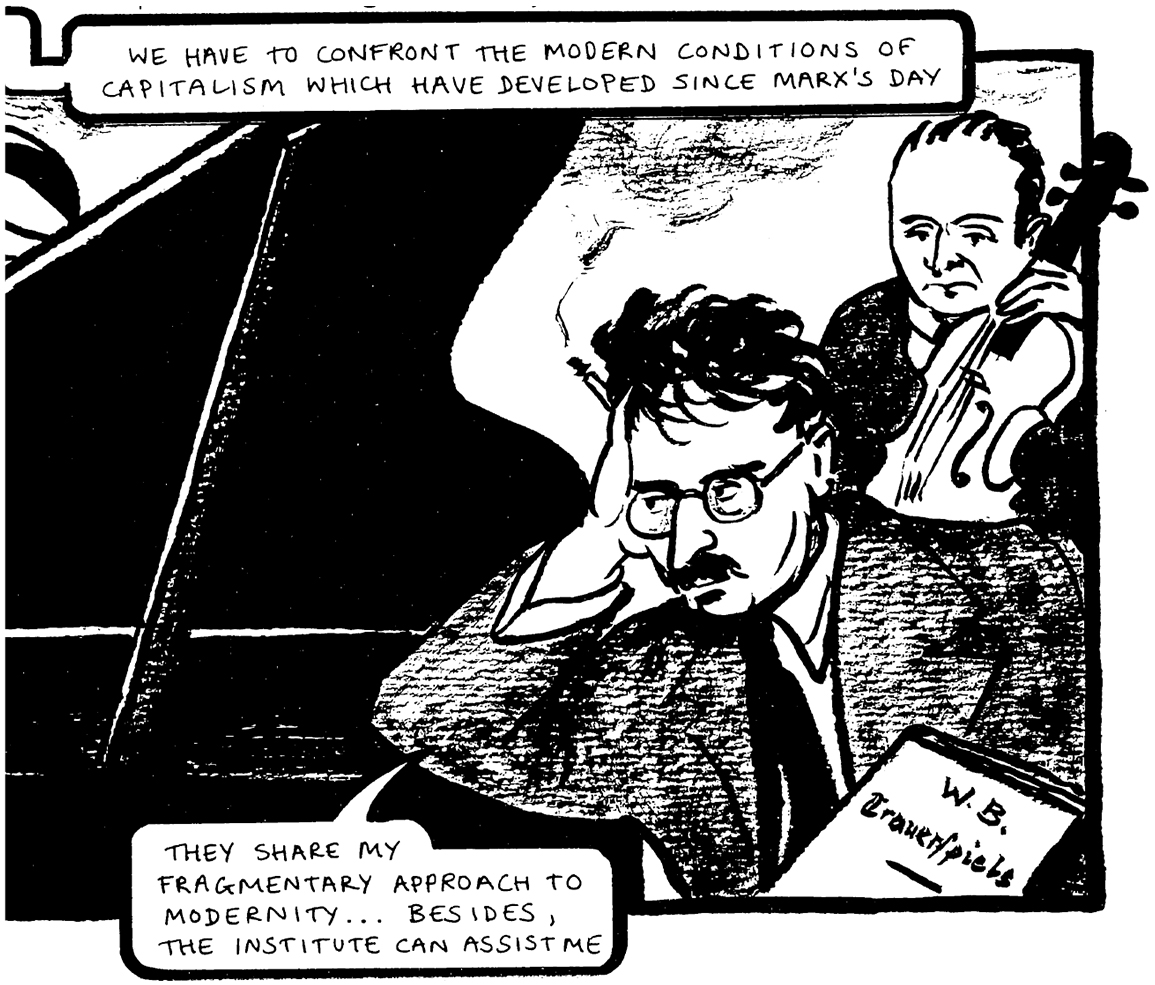

T.W. Adorno (1903–69) was one of the luminaries of the Frankfurt Institute of Social Research, founded in 1923, an influential assembly of social scientists, philosophers and psychoanalysts, aiming to update Marxism and radically dissect modern society. The Institute coined the now freely-used term, “Critical Theory”, as an antidote to the non-critical fashions of phenomenology, logical positivism and dogmatic Stalinist Marxism. Their non-dogmatic theory of “dialectical materialism” and astonishing range of interests in aesthetics, film, mass culture and politics were congenial to Benjamin.

We have to confront the modern conditions of capitalism which have developed since marx’s day They share my fragmentary approach to modernity … besides, the institute can assist me

True, the Institute published Benjamin and financially assisted him. But the irony is that Max Horkheimer (1895–1973), director of the Institute from 1930 onwards, had been among those Frankfurt University academics who had denied Benjamin the Habilitation thesis in 1925.

While the Marxist radicalism of Adorno and his colleagues would seem to presuppose revolution, in reality, as Martin Jay, the historian of the Institute, observed, “… the Frankfurt School chose the purity of its theory over affiliation” to any party, SDP, Communist or any other. Indeed, this was a “school” of Marxism best adapted to conditions which did not yet prevail – the Cold War and the “New Left” currents of the 1950s and 60s. Such “purity” was reflected in Adorno’s elegant, densely-muscled prose style – the polar extreme to Brecht’s simple economy of expression.

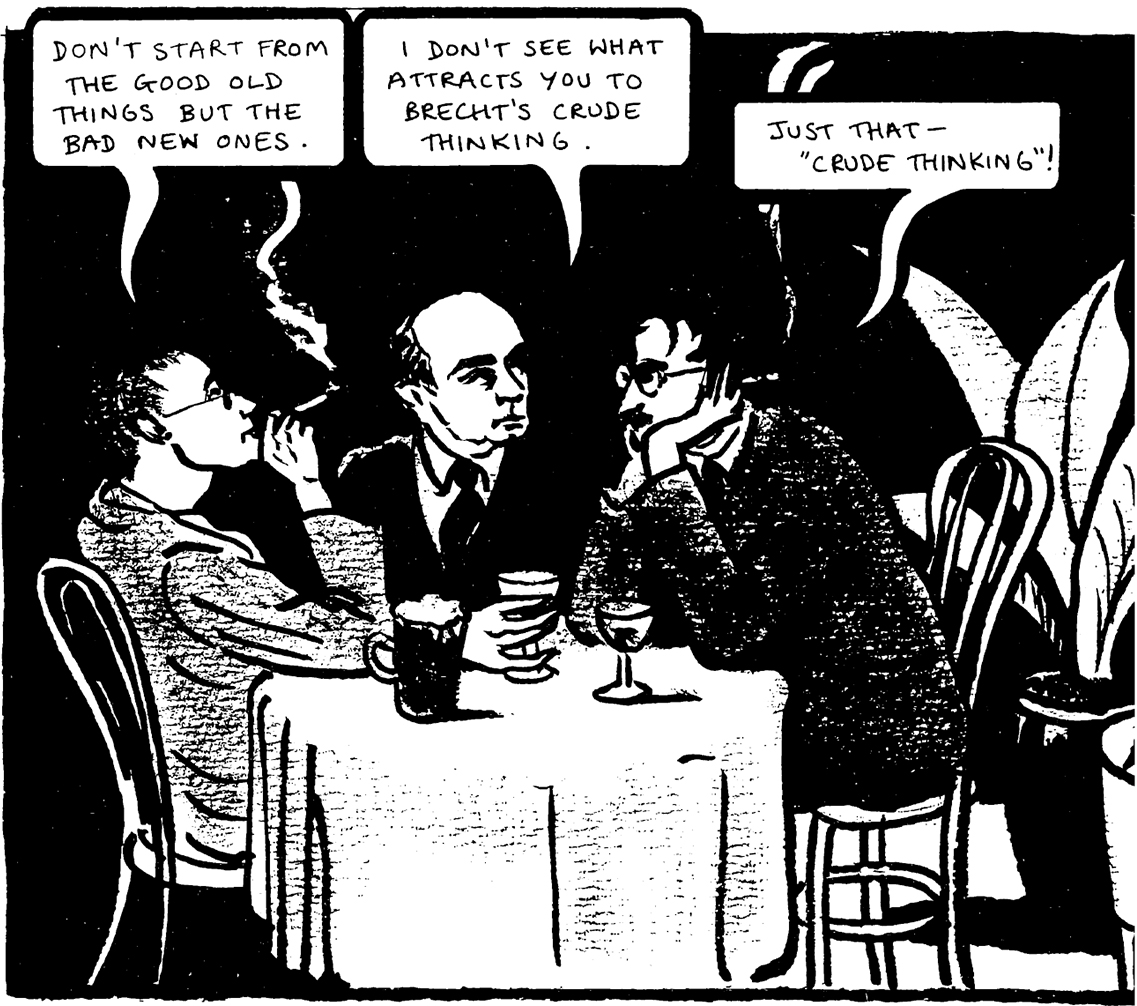

Don’t start from the good old things but the bad new ones. I don’t see what attracts you to brecht’s crude thinking. Just that – “crude thinking”!

“Crude thinking”, characterized by Macheath in Brecht’s best-known work, The Threepenny Opera (1928), means simplifying thought to crystallize it for revolutionary practice.

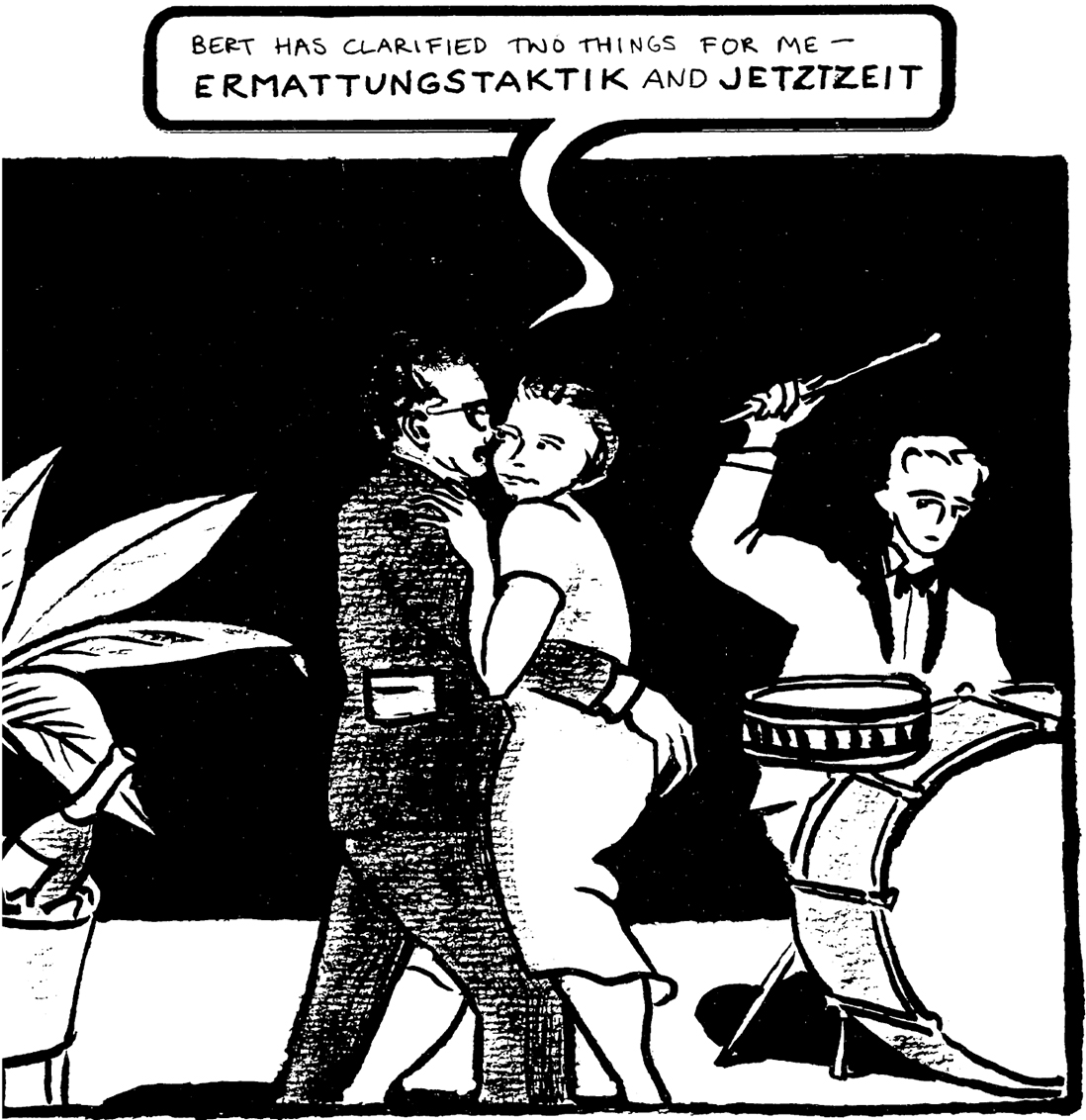

Benjamin had first met “Teddy” at Frankfurt University in 1923; but their association matured in the 1930s. He also frequented Brecht (18981956) in the 30s: they were introduced by Asja Lacis in 1929. Brecht often mercilessly chastized Benjamin, calling him Würstchen (little sausage). Scholem remarked that Benjamin was drawn to Brecht’s harsh “athletic” qualities. But there was empathy and a deep similarity, despite their differences.

Bert has clarified two things for me – ermattungstaktik and jetztzeit

Let’s see what is meant by the Brechtian strategies of Ermattungstaktik (tactics of attrition) and Jetztzeit (the presence of the now).

The “tactic of attrition” is summed up in Brecht’s poem on the Chinese sage Lao Tzu whose maxim is “The hard thing gives way.”

… yielding water in motion gets the better in the end of granite and porphyry. These words ring in our ears today like a promise and a lesson

A “promise and a lesson” of what? Formed by the victories of Fascism and the degeneration of socialism in the USSR, Brecht and Benjamin share a materialist pessimism which is really designed for hope: for a longer-term survival in what they foresee as another Dark Age millennium. Survival needs cunning, “water-like” pliancy and anonymity – the virtues of attrition.

“Only the historian will have the gift of fanning the spark of hope in the past who is firmly convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins.” This is from Benjamin’s “Sixth Thesis on the Philosophy of History” (1940) which expresses his constant vigilance to reclaim the past on behalf of its victims. But how can this square with Brecht’s insistence on the Jetztzeit, “the presence of the now”?

Don’t start from the good old things but the bad new ones. Past and future converge explosively in the present instant. Time stands still.

The revolutionary presence of the now “blasts open the continuum of history”. In this sense, time is redeemed; and in this sense only does the Messiah arrive.

Tactical “crude thinking” in the sly Brechtian manner was necessarily allied to allegorical thinking as Benjamin developed it. As writers, both were also natural magpies alert to the fragmentation of modern experience. The instinct to scavenge the significant fragment and connect dis-similarities in order to shock an audience into fresh recognition – this was the essence of Brecht’s aesthetic.

And its name is the art of montage Allegory reflected the melancholy origin of capitalism. Montage is the un-melancholy form of modern technology.

Brecht had mastered the lesson of montage in the popular media of newspapers, radio and film. Into this form (“the bad new things”), he poured the content of revolutionary Marxism.

From the island of Ibiza (on the move again!), Benjamin contemplated the inauguration of the Third Reich in January 1933.

On the one hand, my funds are low, on the other, common sense bids me honour the in augural festivities of the third reich with my absence.

Benjamin was already considering exile. He was in no doubt (and with chilling foresight) that Nazi Germany was “a train that does not leave until everyone is on board”.

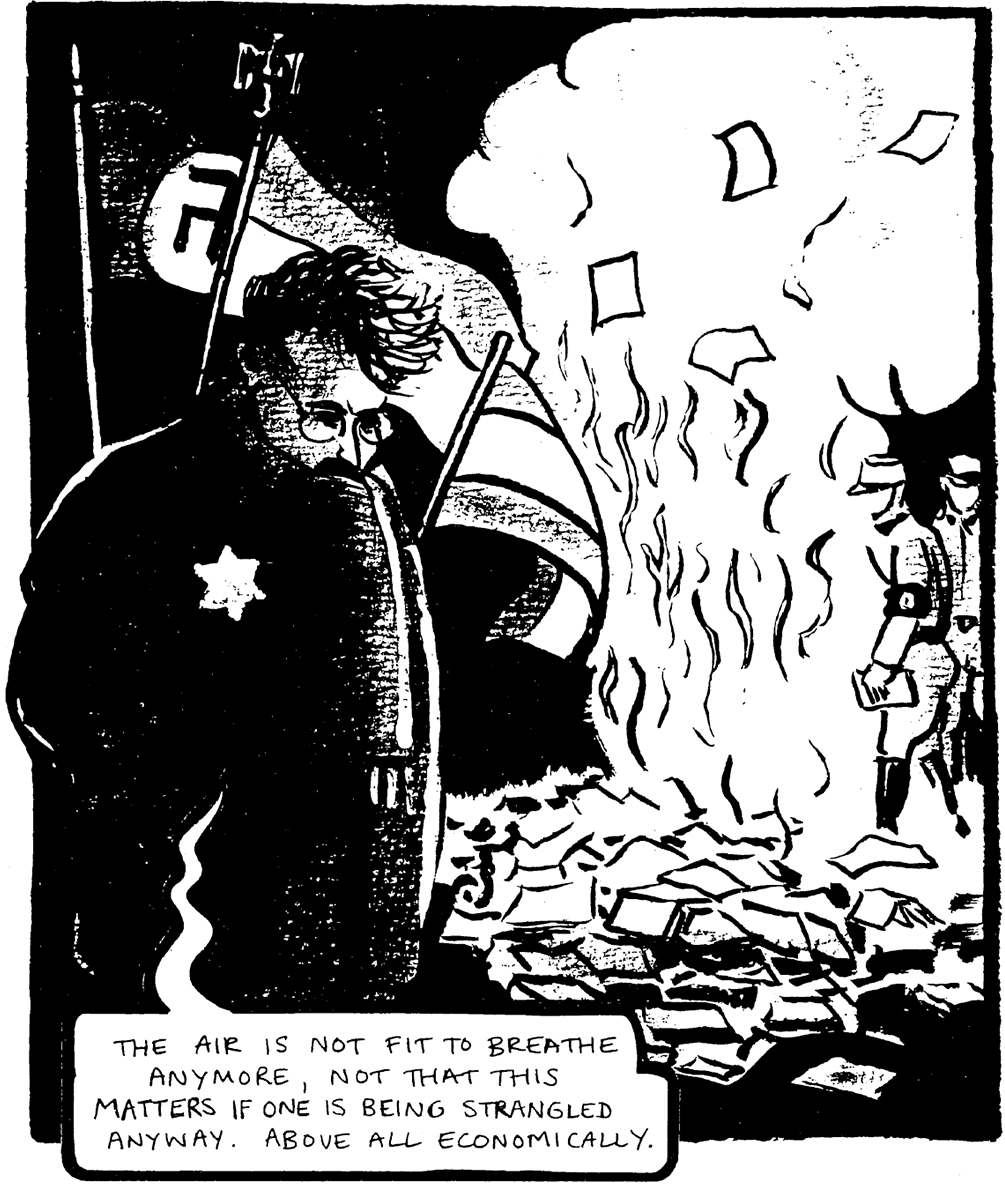

Benjamin did return to Berlin and witnessed the early months of book burnings, violent street scenes and Hitler’s hysterical speeches.

The air is not fit to breathe anymore, not that this matters if one is being strangled anyway. Above all economically.

His own economic situation was deteriorating badly. Newspaper editors would not allow him to publish, except under a pseudonym. In the middle of March, he left for Paris. “Where else but Paris?”

Benjamin often visited Brecht in his own exile at Svendborg, Denmark. They heard Hitler’s 1934 Reichstag Speech on the radio and compared the “great dictator” to the film star “little tramp”, Charlie Chaplin.

The fashionable ideal set by hitler is not that of the army but rather of the “distinguished gentlemen”. So much glitter surrounding so much shabbiness. Hm! But you also have to imagine chaplin as a mafioso gang leader. It is of no service in understanding hitler to represent him as a cartoon gangster.

Brecht’s play, The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui (1941), depicted Hitler as a small-time racketeer who makes it big by “massaging his image”. This was scathingly criticized by Adorno.

In Paris, 24 April 1934, at the Institute for the Study of Fascism, Benjamin gave his notorious reading of “The Author as Producer”. He called on the artists on the left “to side with the proletariat”. In Paris at the time, this call was not radical; the approach, however, was. In true Brechtian style, Benjamin urged the “advanced” artist to intervene, like the revolutionary worker, in the means of artistic production – to change the “technique” of traditional media.

Transform the apparatus of bourgeois culture. Do not adopt the aesthetically conservative position of presenting a revolutionary content by means of traditional forms.

As a model of “radical form and content”, Benjamin offered the newspaper: “a vast melting-down process which not only destroys the conventional separation between genres, between writer and poet, scholar and popularizer, but also questions even the separation between author and reader.”

The place where the word is most debased – the newspaper – becomes the very place where a rescue operation is mounted.

Benjamin had apparently digested Brecht’s crude-thinking formula of “bad new things” and the hope placed in revolution by attrition. Despite this, Brecht would always claim that he never knew what Benjamin was on about!

Benjamin’s 1936 essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, is perhaps his best-known but often misunderstood work. Let’s begin by sampling Benjamin’s analysis of cinema as a technical reorganization of reality.

The reaction that the dadaists tried to provoke in their audience was achieved in a more natural way by the movies of charplin.

“The film is the art form that is in keeping with the increased threat to his life that modern man has to face.” That “threat” was evidenced by the overture of the Spanish Civil War (1936–39).

The first Blitzkrieg bombing of an urban population befell the Basque capital of Guernica (1937), “immortalized” by Picasso’s painting of that event. We might ask, in Benjamin’s spirit, how does the painter compare with the camera-man in such an age of mass destruction? The painter is like the magician who heals the sick by the “laying on of hands”.

The camera – man is instead like the surgeon who cuts into the patient’s body!

Benjamin was deeply concerned with the consequent impact on art of the mass technologies of reproduction. What happens to an “immortal” painting – say, Van Gogh’s Sunflowers – when it is mechanically reproduced on postcards, posters or even postage stamps without regard to its original size, location or history?

It will lose its aura …

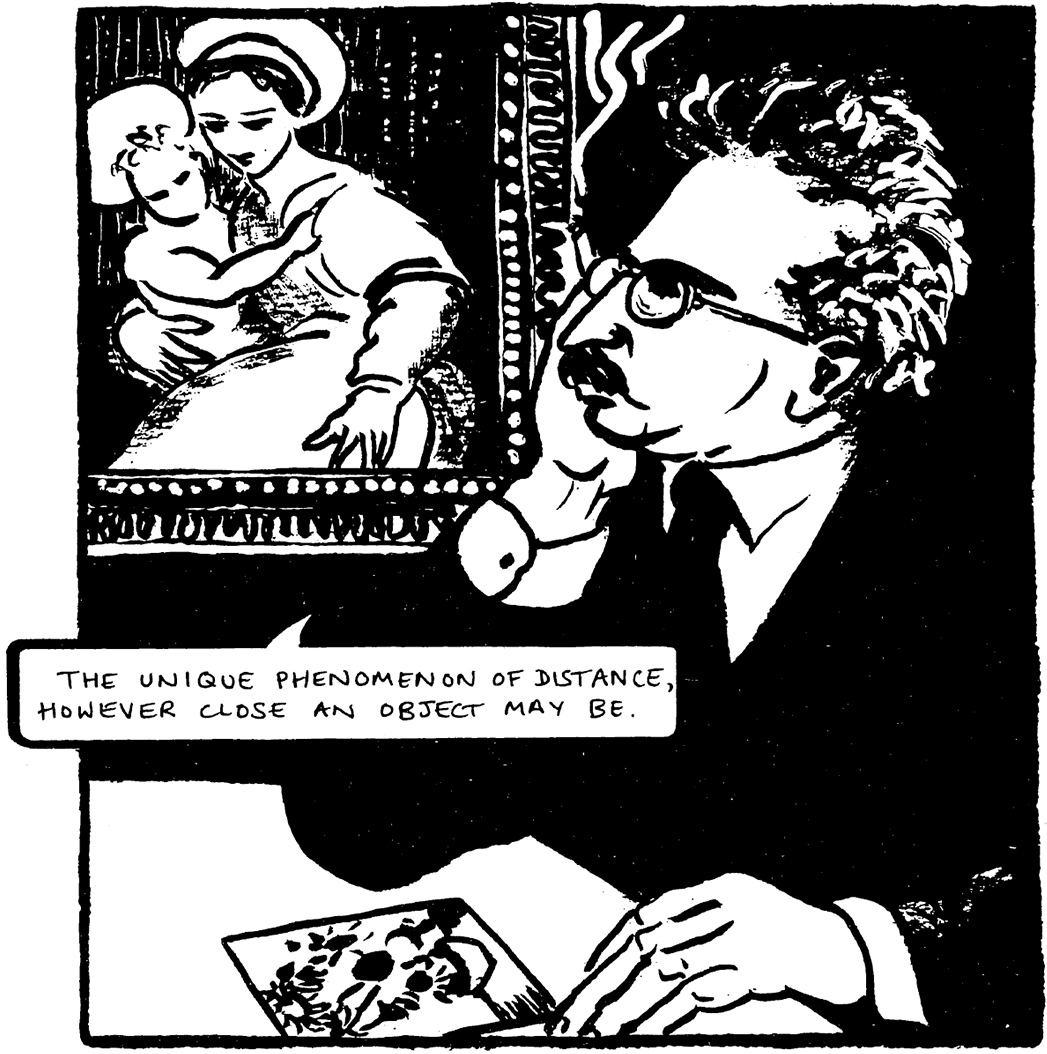

What does Benjamin mean by “aura”? It refers to the customary historical role played by works of art – their “ritual function” – in the legitimation of traditional social formations.

Throughout the history of culture, works of art depended on a status: they owed their existence primarily to their implication in the processes of social integration. As an object of religious veneration and worship, the work of art acquires a “halo” of uniqueness and authenticity. And so, Benjamin arrives at his famous definition of the aura …

The unique phenomenon of distance, however close an object may be.

Auratic “distance” is in this sense unmeasurable. We should also note that Benjamin’s terminology here is still guided by Riegl – and so too is the brief history of art he develops.

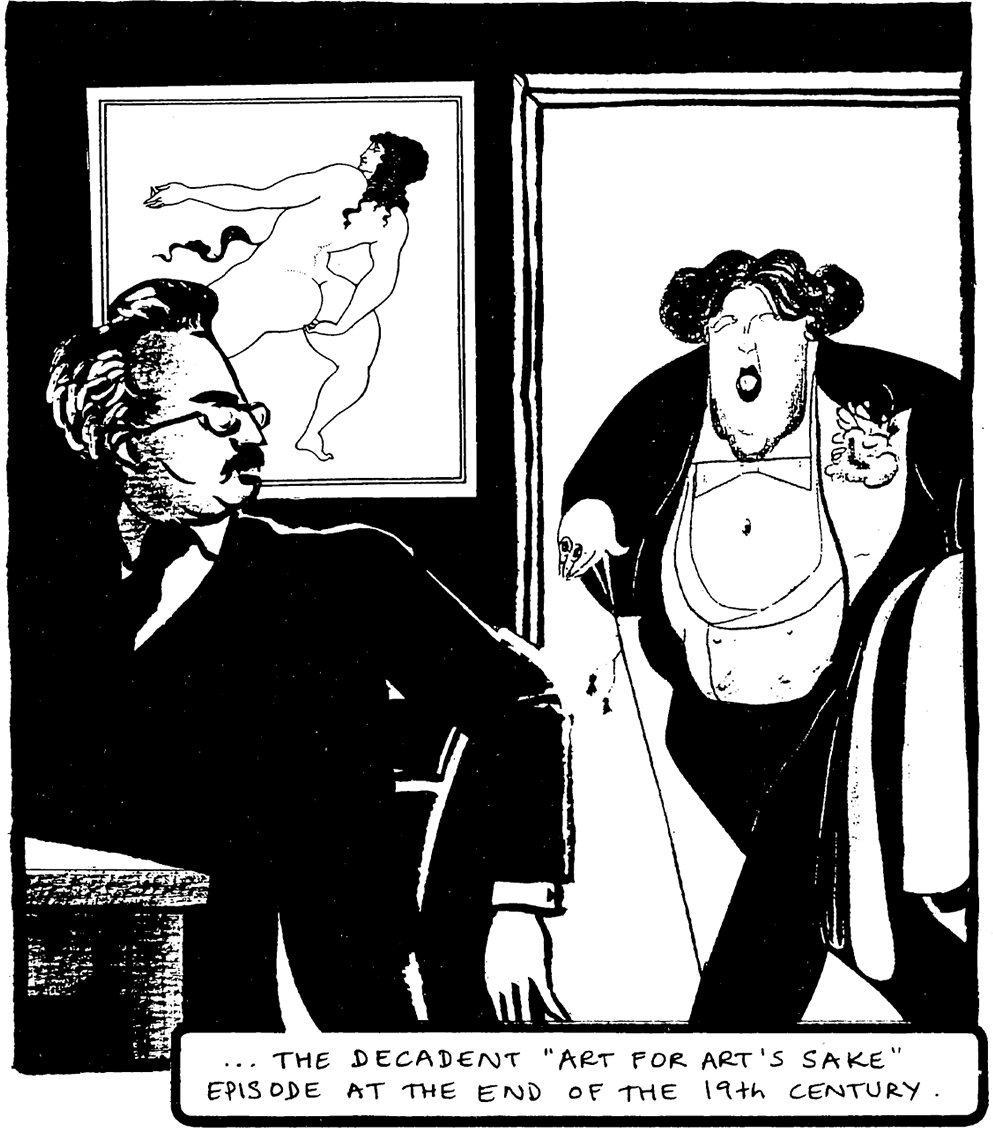

Renaissance painting, with its cult of secular beauty, first challenged the ritualistic basis of artistic production. A long, hard struggle for artistic autonomy then began, which, via Romanticism, culminated in the pinnacle of aestheticism …

… the decadent “art for art’s sake” episode at the end of the 19th century.

This last decadent attempt to restore the “venerable” aura within the ghetto of aestheticism occurred as a reaction against the rampant commodification of art under 19th century capitalism. But the emergence of “Art for Art’s Sake” coincides with photography and the crisis of painting.

The increasing intervention of technology in the production and reception of works of art tends to dissolve them and, in the 20th century, results in the decay of the aura. To substitute a plurality of mechanically reproduced copies for the unique original must destroy the very basis for the production of auratic works of art – that singularity in time and space on which they depend for their claim to authority and authenticity.

What I’m talking about is the contamination and eventual transformation of art by technology.

Although “transformation by technology” might contain radical potentials for the political deployment of art, Benjamin was in fact equivocal, because he could see how it could also be co-opted to support traditional or even reactionary and Fascist politics. Indeed, his adoption of Brechtian “crude” tactics becomes fully intelligible in the glare of Fascism’s own crass but powerful aestheticization of political violence. Benjamin’s counterposal was to meet force with force. “Mankind which in Homer’s time was an object of contemplation for the Olympic gods, now is one for itself …”

Mankind’s self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order.

Hence, his famous proclamation: “This is the situation in politics which Fascism is rendering aesthetic. Communism responds by politicizing art.”

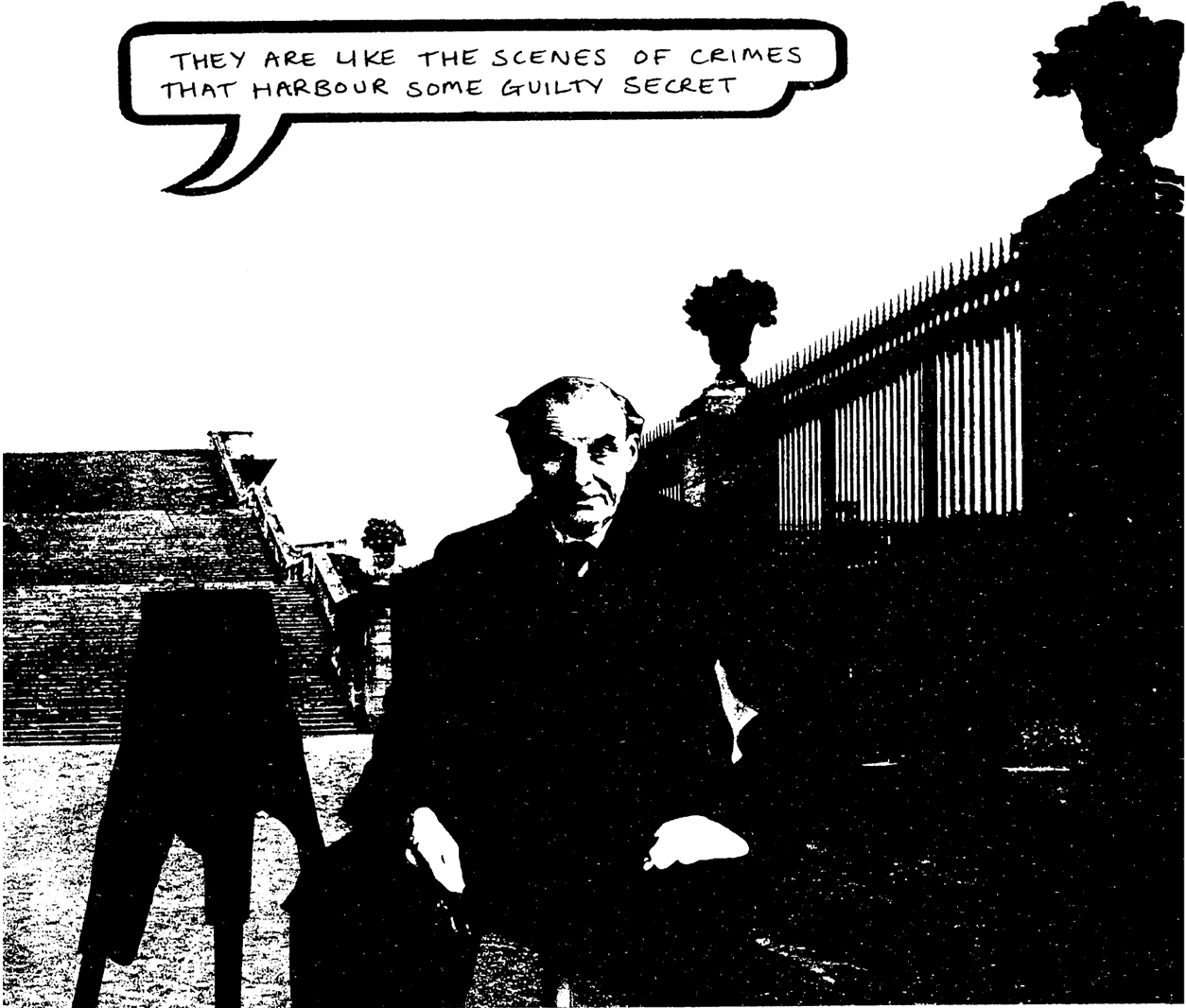

The loss of “auratic distance” might signal the era of a new ethical order based on the universal equality of things and the sovereignty of individuals. In short, the end of fetishized commodities and alienated consumers. But his ambiguity about this loss is shown in an earlier essay, “A Short History of Photography” (1931). Here he praises Atget who always photographed Paris without people, as a surreal empty location.

They are like the scenes of crimes that harbour some guilty secret

He proclaims the photographer’s task as “to uncover guilt in his pictures”. What guilt? There is no evidence of any crime in Atget’s pictures: they are empty. It is not so much that Atget liberates the object from the aura, but that the power of his photographs resides in their suggested possession of an aura.

Benjamin has been shown to be mistaken. Mass reproduction actually increases aura – in an unforeseen way. Think of Van Gogh’s Sunflowers again. Its mass-reproduced availability has in fact multiplied the aura of its cash-value and re-distanced it to the remote region of the uniquely priceless.

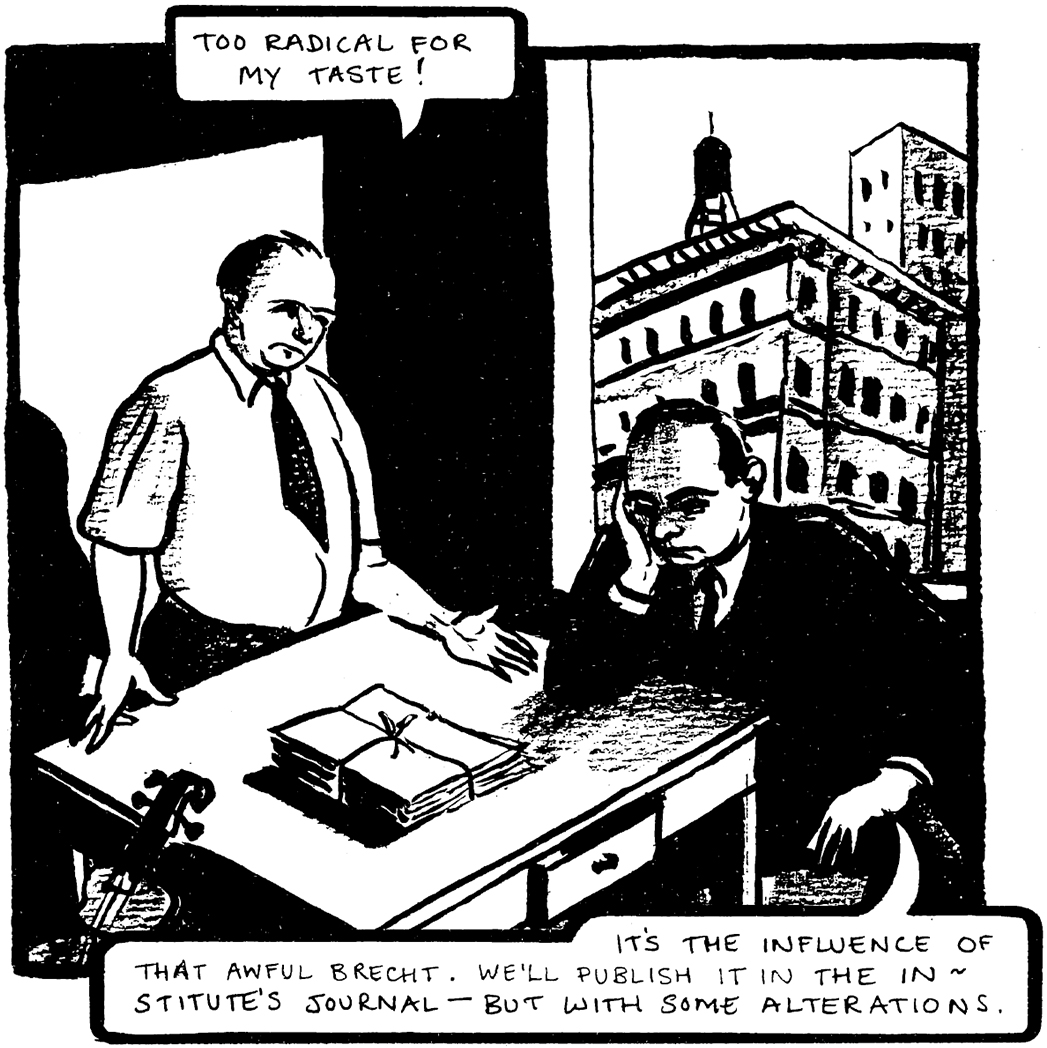

But in 1936, for different reasons, the essay troubled Max Horkheimer (now exiled with other Institute members in New York) and Adorno.

Too radical for my taste! It’s the influence of that awful brecht. We’ll publish it in the institute’s journal – but with some alterations.

Beyond the time-bound circumstances of politics and polemics, Benjamin’s “mistakes” remain creative, precisely because of the unresolved ambiguities of the “aura” that have yet to be explored.

Adorno, then in England until his move to New York in 1938, would often see his friend in Paris. He criticized Benjamin’s essay for its “undialectical” acceptance of mechanically reproduced art and its rejection of all autonomous art as being inherently “counter-revolutionary”. It failed to consider that some modernist art had radically divested itself of the retrograde aura in favour of a fragmentary and dissonant formal aesthetic structure – for instance, the twelve-tone music of Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951).

Such works are anti-auratic and have a socially critical function. think of franz kafka. I have been thinking of kafka, a lot.

In fact, Benjamin had already written an essay, “Franz Kafka”, in 1934. He chose to write this commemorative piece on the 10th anniversary of Kafka’s death (1883–1924) under the thatched roof of Brecht’s cottage in Svendborg where he suffered Bert’s acerbic criticisms.

Kafka’s images are good, but the rest is pure mystification. It’s nonsense. You have to ignore it. Depth doesn’t get you anywhere at all … The conversation then broke off to listen to the news from vienna.

Benjamin’s intense engagement with Kafka’s work began with a short esoteric text, “Idea for a Mystery Play” (1927). He reviewed Kafka’s story, “The Great Wall of China”, for the radio in 1931. But why discuss Kafka with an unsympathetic Brecht? Scholem has wisely commented on this: “In those reflections on Kafka, his ‘Janus face’, as Benjamin liked to call it, assumed sharp contours. One side of it was offered to Brecht, the other to me.”

We are nihilistic thoughts, suicidal thoughts that come into god’s head. As an angel of illness, I have kafka at my bedside. To understand the kabbala, nowadays one has to read kafka first, particularly the trial.

Scholem had introduced Benjamin to the Kabbala, an esoteric system of Jewish Gnosticism, and its classic text, the 13th century Zohar, written in Spain. Scholem had also advised him to begin his inquiry on Kafka with the Book of Job: “… or at least with the possibility of divine judgement, which I regard as the sole subject of Kafka’s production. Here, for once, a world is expressed in which redemption cannot be anticipated. Go and explain this to the goyim!” Goyim, i.e., the Gentiles – meaning presumably Brecht?

Kafka’s outlook is that of a man caught under the wheels!

Strange, that Benjamin’s essay, steeped in years of Jewish mysticism, should coincide in 1934 with “The Author as Producer”. So, which is the “real” Benjamin – the Marxist? the Jewish mystic? We should not see Benjamin’s plural areas of work in contradiction or opposition to each other, but rather in continuous dialogue with each other. Intellectual, spiritual and political commitments need not be forced into a straitjacket, as Benjamin himself stated.

My stance is to behave always radically, never consistently when it comes to the most important thinks.

As the Zohar says: “… then will the worlds be in harmony and all will be united into one, but until the future world is set up, this light is put away and hidden.”

Paris was Benjamin’s “chosen city”, as Martin Jay writes, “both as the site of his exile and as the controlling metaphor of his work”. This is early evident in his passion for the “allegorist” poet of Paris, Charles Baudelaire. But the idea for an article on the Paris arcades began on a walk with his friend Franz Hessel, then, in 1926, collaborating with Benjamin on the translation of Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu.

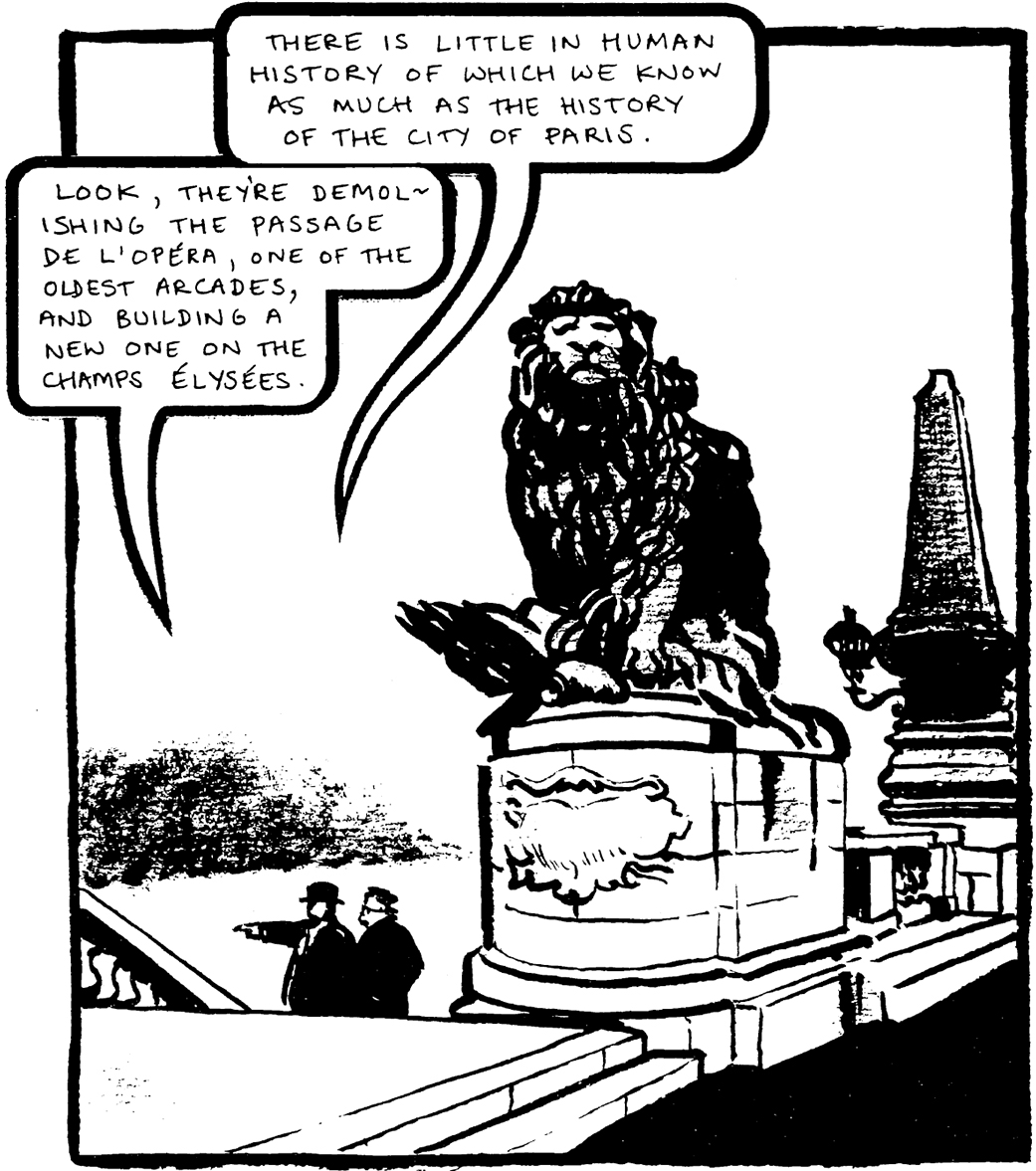

There is little in human history of which we know as much as the history of the city of paris. Look, they’re demolishing the passage de l’opéra, one of the oldest arcades, and building a new one on the champs élysées.

The first Paris arcades, constructed early in the 19th century, sometimes enclosed a number of streets under a glass roof. What attracted Benjamin was the simultaneity of being both outside and inside, the Neapolitan experience of “porosity” again, but especially the fashionable rows of shops with their dazzling displays of commodities behind glass facades.

Here is the “open sesame” entrance to penetrating the mystery of commodity fetishism …

Notes, plans and drafts began to accumulate between 1927 and 1929 for an essay with the indicative title of “Paris Arcades: A Dialectical Fairytale”.

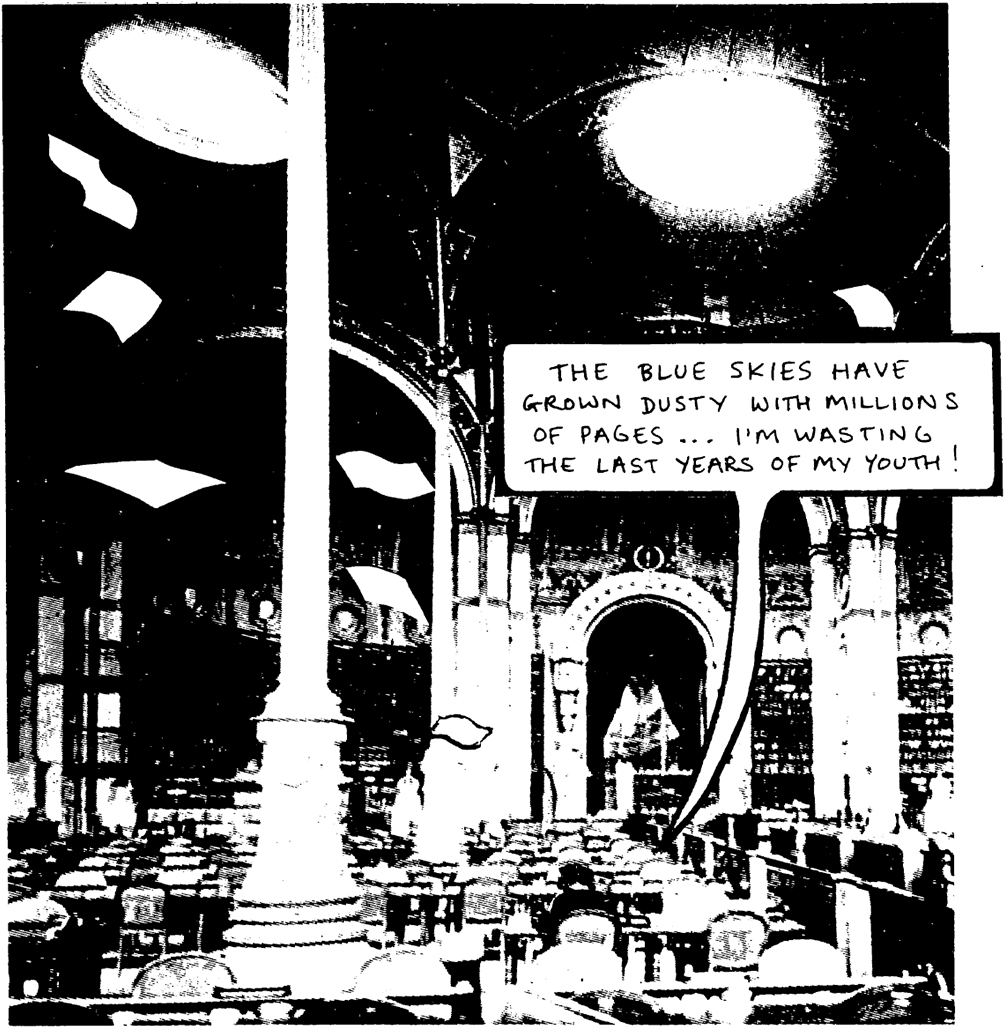

Discussions in 1929 at the resort of Bad Königstein with Adorno, Horkheimer and Asja Lacis gave the arcades project clearer Marxist shape. In Benjamin’s mind, it had close allegorical links with his Trauerspiel thesis as a further epistemological “tragic drama” of the 19th century. Some five years later, in his Paris exile, research had got out of hand as Benjamin burrowed like a mole deep into the archives of the Bibliothèque Nationale.

The blue skies have grown dusty with millions of pages … I’m wasting the last years of my youth!

Benjamin had not foreseen that his project would inflate into a massively unfinishable task – a stage of grim battles with the New York Institute over publication, and a race against the clock as war threatened.

Unfinishable or not, what was Benjamin’s aim? It was to treat the bygone relics of the arcades period – its architecture, technologies and artefacts – with “utmost concreteness” as the precursors of modernity, in other words, as the past witnesses of the present. This was not merely “industrial archaeology” but an allegorical prompting of these dead witnesses to speak again of their “secret affinities” to our own time.

I shall give voice to the origins of commodity fetishism.

Ideology is whatever we take for granted as the God-given, natural or inevitable “facts” of economic, social and political life. Marx had performed a first deconstruction of the ideological assumptions underpinning the capitalist economy. The problem was that Marxism’s faith in the march of historical progress had blinded it to other compulsions that might account for historical regressions. Fascism, in Benjamin’s maverick view, was just such a phenomenon. It was not a sudden regression to barbarism but a return of compulsions already prepared deep within the “advanced culture” of 19th century capitalism. Freudians might call it “the return of the repressed”. Another problem was that Marxist ideological criticism offered theories about social experience, not the experience itself.

The point is to show how commodities are transformed sensually in their immediate presence and become phantasmagoria. Historicism Notes of dreaming & waking Types of experience Ideas of progress Material relics of the 19th century Key writers Epistemology principles

Phantasmagoria, a term used in Marx’s Das Kapital, were optical devices for rapidly shifting the size of objects on a screen. Here was Benjamin’s clue to depicting sensual immediacy. Capitalist modernity had come to focus in Paris under the monarchy of Louis Philippe (1830–48) and the Second Empire of Napoleon III (1852–70). How could he show the regressive elements and utopian potentials of this culture in graspable, powerful “dialectical images”? He began systematizing his mountain of research notes into colour-coded index cards.

Another guide to this vast unending maze of materials was a “blueprint” outline that he provided for Adorno and the Institute in 1935, “Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century”, which we’ll now look at.

1. Fourier, or the Arcades

Commercial arteries cut through entire blocks of houses whose owners gain from property speculation.… How do we experience the regressive and utopian contradiction of these arcades?

Gas-lighting for the first time Glass and iron married in architecture But the function of iron is disguised as ancient greek columns Everything is artificial!

Riegl’s method is again obvious in Benjamin’s attention to the details of ornament, the tactile and optical elements.

Here, in these transitory arcades, even in the fleeting fashions on display in its shops, we find traces of a utopian wish for a completely satisfactory system of social production. Charles Fourier (1772–1837), the social philosopher, envisaged a bizarre utopia that he named Harmony. And where did he imagine his utopian folk would dwell?

Harmony will be a city of arcades … Construction fills the role of the unconscious

Glass and iron construction, the arcades and the panoramas arrive together. Panoramas are painted landscape vistas that unscroll before the spectators: perfect deceptions of day turning to night, moon rises and waterfalls. They introduce the countryside into the city – another utopian image – and point ahead, beyond photography, to cinema.

Photography as a marketing and advertising device will enormously expand commodity sales. Photography which renders traditional painting obsolete will liberate the colour elements of cubism.

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1789–1851), inventor of the daguerreotype in 1839, began as a panorama painter.

World Exhibitions, begun in London in 1851, are pilgrimages to the commodity phantasmagoria. Commodities are now mass entertainment in which people themselves become commodities. This is the secret behind the art of Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard Grandville (1803–47) which ends in his madness. Grandville’s illustrated fantasies go to the extremes of utopianism and regression.

Utopian in extending the modernizing character of the commodity to the universe itself.

Regressive in its perfect cynical grasp of commodity fetishism

Grandville stitches the living body to the inorganic. Fetishism is indeed “subject to the sex appeal” of inanimate objects. Fashion will then dictate the ritual by which the commodity fetish demands to be worshipped.

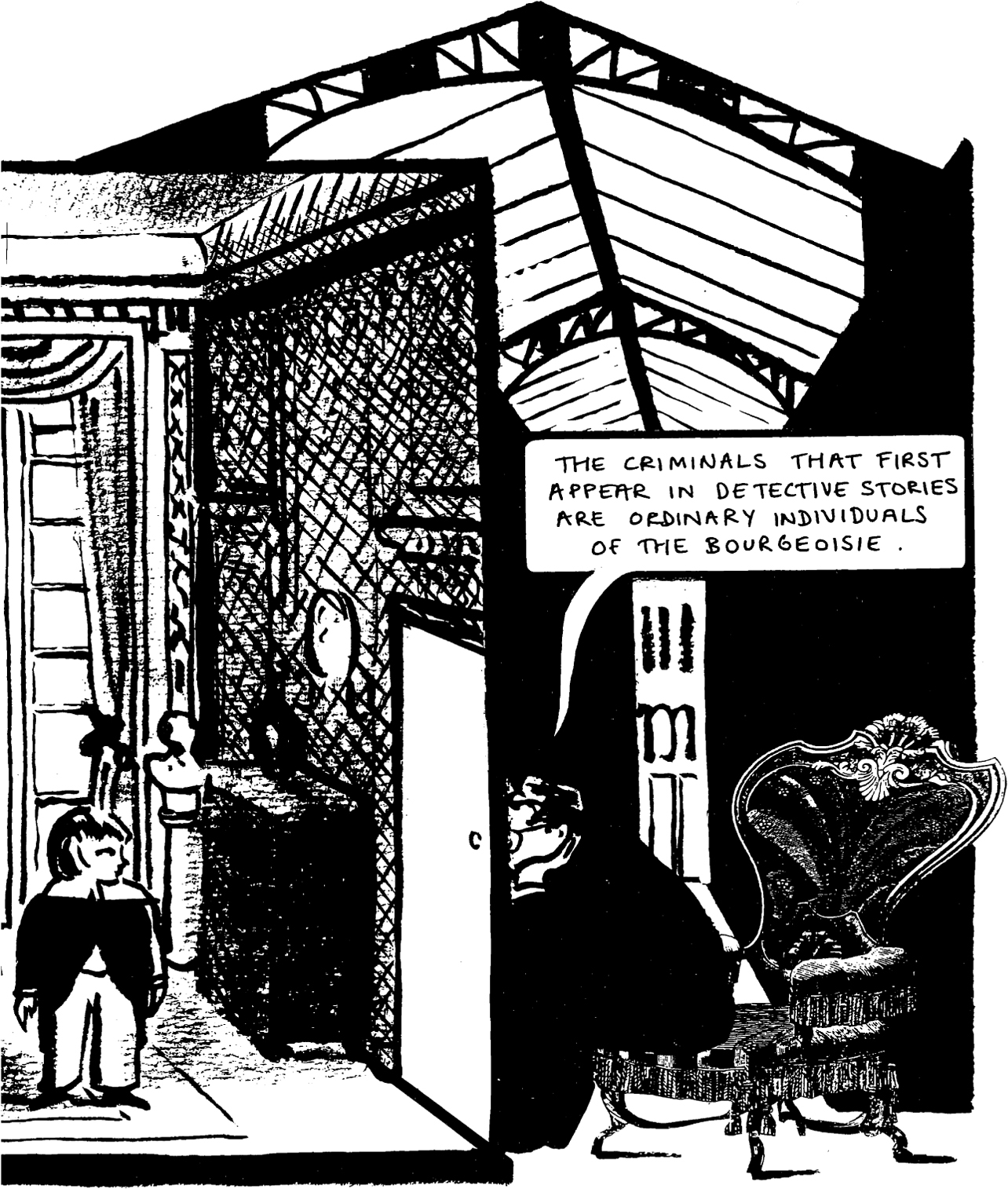

Not for nothing was Louis Philippe known as the “citizen-king”, the epitome of bourgeois domesticity, with his ten children, top hat and rolled umbrella, who mixed freely with Parisians in the streets. With his reign comes the “private person” who must at all costs maintain the illusion of an intimate living space totally separate from the office work space. Hence, the phantasmagorias of the bourgeois interior: the drawing-room as a private box in the world theatre.

The collector is the perfect occupant of this interior universe

But occupancy leaves traces – and, as in Atget’s photographs, there are imprints of guilty secrets. Edgar Allan Poe (1809–49), who invented the detective story in 1843, captured this eerie quality in his “philosophy of furniture”.

The criminals that first appear in detective stories are ordinary individuals of the bourgeoisie.

The arcade liberates the window-shopper’s gaze. Baudelaire portrays this new “man of the crowd”, the flâneur – the idler; the urban stroller – flip side of the office-hours bourgeois.

The flaneur merges with that undomesticated conspirator, the bohemian artist, of uncertain economic status.

And with other new figures, the dandy and the snob.

The bohemian’s natural interface is with prostitutes – and death – as we find in Puccini’s La Bohème (1896). Baudelaire’s last poem in Flowers of Evil, “The Voyage”, ends with the summons, “O Death, old captain, it’s time, let’s weigh anchor!” But what is his destination? “To the depths of the Unknown, in quest of something new!”

The novelties of fashion and commodities

Baron Georges Eugène Haussmann (1809–91), Prefect of the Seine under Napoleon III, called himself “an artist in demolition”. To him we owe the Paris we see today, with its great boulevards and long perspectives. He destroyed the working-class areas of the inner city to build his ideal vistas. His real purpose was to prevent the building of barricades, a strategy of the 1848 revolution.

But workers displaced to the suburbs meant that the rich centre was now surrounded by a permanently troublesome red belt!

So, despite Haussmann’s regressive efforts, an unexpected utopian element creeps back in. Barricades go up again in the Commune uprising of 1871 – and the May Events of 1968 – with plenty of other resistances in between!

The outline we have just seen – hardly a dozen pages – although useful as a guide, is also misleading. It barely suggests the complex montage of quotation and commentaries that Benjamin’s plans would never finalize. This 1936 “blueprint” did initially impress Adorno enough to approach the Institute and plead financial support for Benjamin’s “masterpiece” project. Adorno’s enthusiasm was soon replaced by another detailed criticism. And so began a see-saw battle, lasting until 1939, with the Institute “money men” over the publication of two scaled-down essays on Baudelaire.

Sorry to be the messenger of bad news again, but your dialectics still lack mediation. What choice do I have but to rewrite once more, if I want to be published? This is the last of my large scale defeats!

“In the ruins of great buildings, the idea of the plan speaks more impressively than in lesser buildings, however well-preserved they are.” Benjamin’s own words from the Trauerspiel assure us that all is not lost for an interpretation of his arcades project. Virtually all of his crucial works in the 1930s can be understood as pieces out of the unfinishable whole. But by the spring of 1939, Benjamin’s life was in grave peril. The Gestapo was seeking his expatriation – evil tidings for a Jew openly active in Communist circles. At their last meeting in January 1938, Benjamin had resisted Adorno’s pleas to escape Paris for New York.

There are still positions in europe to defend.

Hitler’s invasion of Poland, 1 September 1939, followed in two days by France and Britain’s allied declaration of war, led to the “precautionary” measure of detention in French internment camps for exiles like Benjamin. Released at the end of November 1939, he returned to Paris.

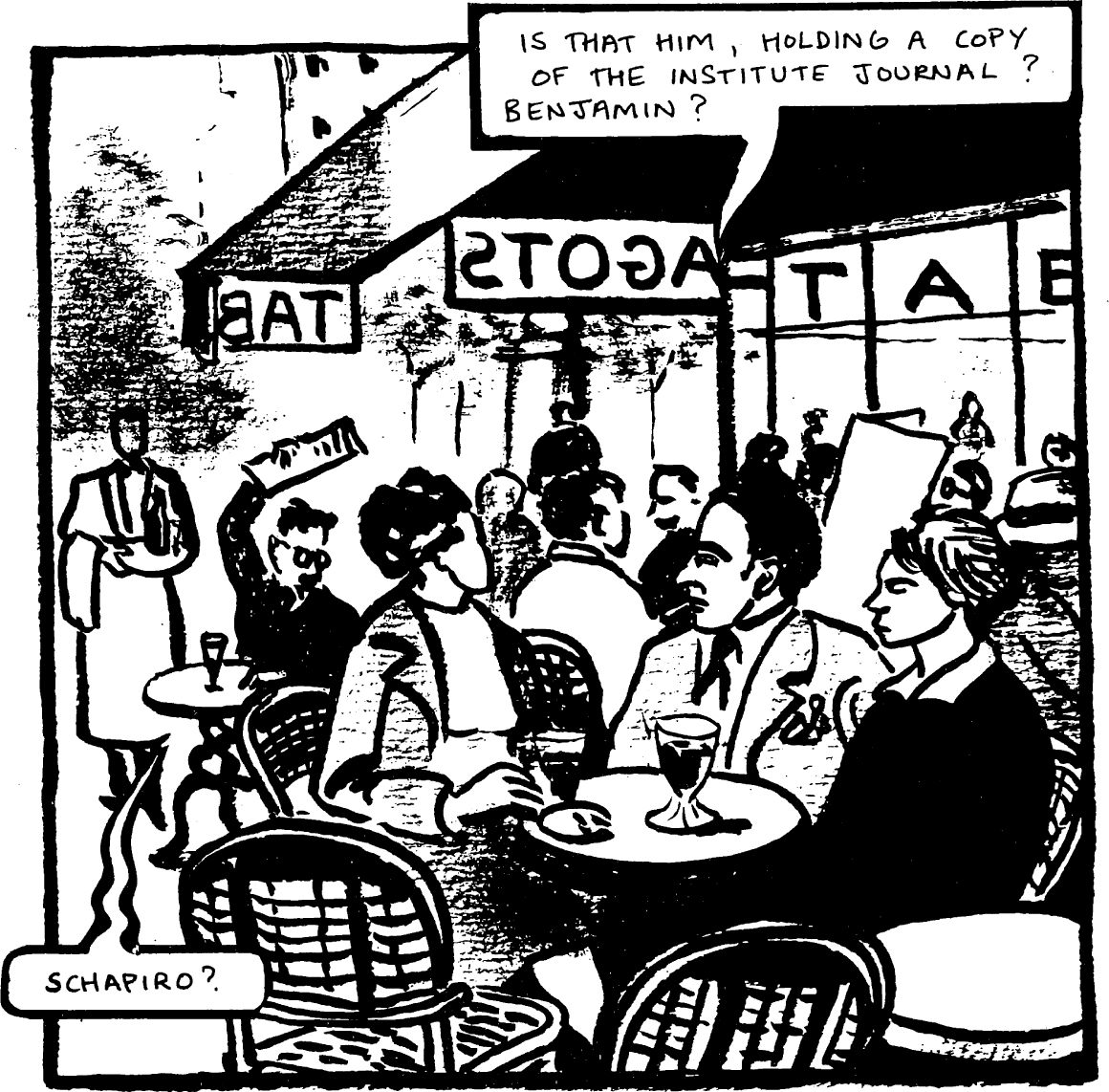

Prior to his internment, and just before the outbreak of war, Benjamin had been visited by an emissary from the Institute in New York. Meyer Schapiro, a young art historian, a scholar of Benjamin and Riegl’s works, was sent to persuade him to emigrate at once. On the phone, Benjamin suggested a rendezvous at the bistro Les Deux Magots. But how would they recognize each other? Benjamin replied, “You’ll see.” Schapiro and his wife Lillian waited in the bistro …

Is that him, holding a copy of the institute journal? benjamin? Schapiro?

Schapiro did not succeed. Why did Benjamin not take this last opportunity to flee? Was it perhaps that he had determined to work on the arcades until the very last moment?

In the winter of 1940, Benjamin undertook his last known writing, “Thesis on the Philosophy of History”. These 18 brief aphoristic “Theses” were to serve as provisional theoretical armatures to Baudelaire’s central role in the arcades project. But they were also a response to the “new war” in its global synopsis of his generation’s entire experience. They were not meant for publication, as Benjamin emphasized in a note to Adorno.

I fear the connections they make between theology and historical materialism will be misunderstood.

He was right – the “Theses” are among the most often quoted and abused of his writings. Inevitably, too, they remind us of Marx’s own “Theses on Feuerbach” (1845), particularly the 11th and last. “The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.”

From Thesis 1. Baron von Kempelen’s chess machine was able to play winning games. An automaton puppet in Turkish dress, smoking a hookah pipe, sat playing at a chessboard on a large table. Mirrors cleverly gave the illusion that the table was entirely transparent; but, inside, a little hunchback, expert at chess, guided the puppet’s every move.

The puppet called "historical materialism" should win every time – if it enlists the services of theology, which as we know today is small and ugly and must keep out of sight

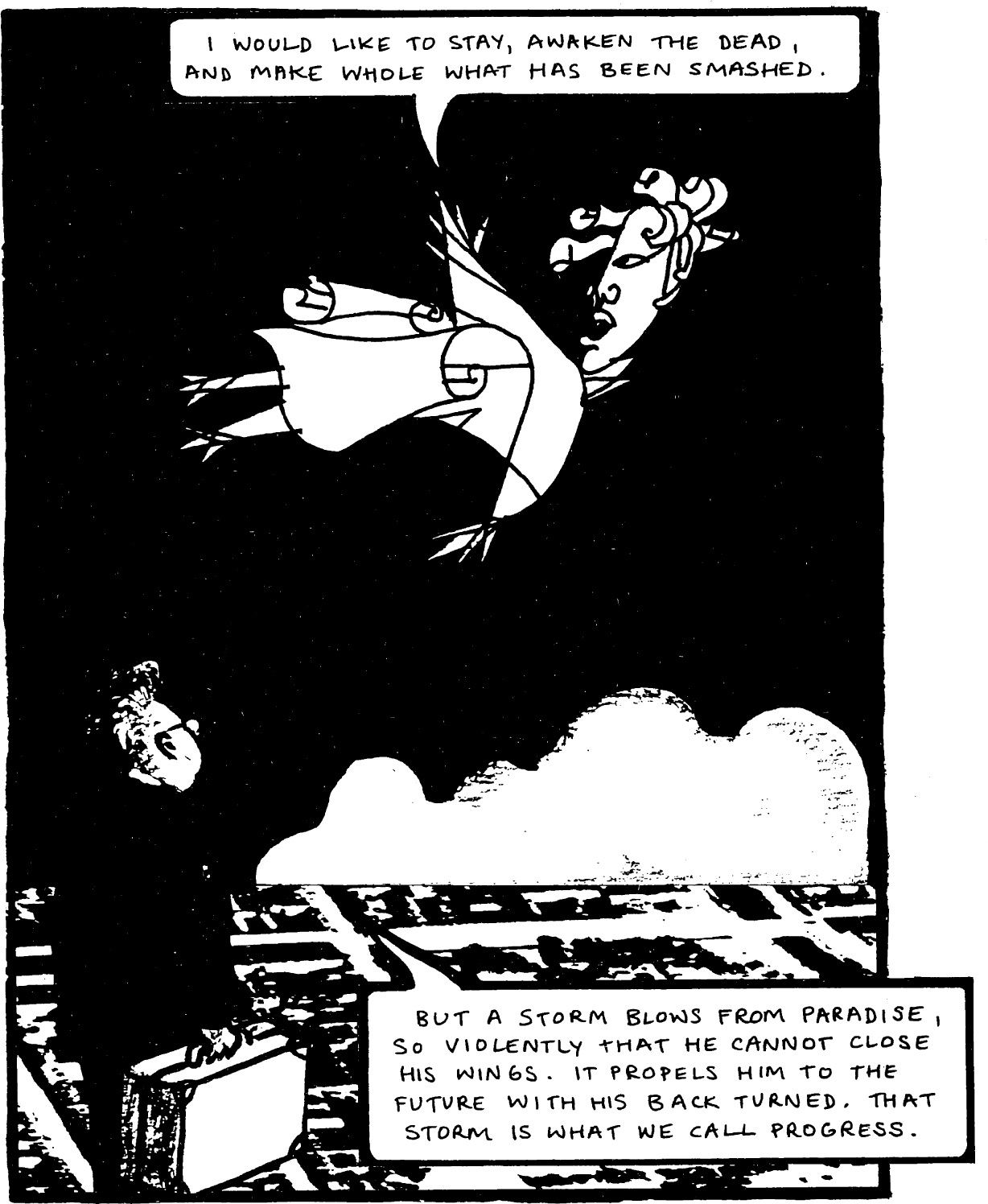

From Thesis 9. Klee’s “Angelus Novus” again. This is how we can picture the angel of history – his face turned towards the past. Where we see a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe piling wreckage upon wreckage at his feet.

I would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm blows from paradise, so violently that he cannot close his wings. It propels him to the future with his back turned. That storm is what we call progress.

France collapses in the Nazi Blitzkrieg of May-June 1940. The Germans occupy Paris on 14 June; the Gestapo seize Benjamin’s apartment. The only escape left is to head south and cross the Pyrenees into Spain. But before he goes, Benjamin entrusts his arcade notes to a librarian at the Bibliothèque Nationale: Georges Bataille (1897–1962), dissident Surrealist, anti-philosopher and eroticist.

... from thesis 7. There is no document to civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism. Ah well, he could have been useful in my college of sacred sociology...

Benjamin, with other refugees, did manage to cross the Spanish border and reach the coastal town of Portbou. But the Spanish government had suddenly revoked all transit visas that might have got him to Lisbon and eventually to safety in America. Refugees were to be sent back to France the next day. Despairing, in ill health and mortally fatigued, Benjamin swallowed an overdose of morphine tablets that night. The official date of his death on the Portbou register is 26 September 1940. He was 48 years of age. His possessions were handed over to a Spanish court on 5 October 1940.

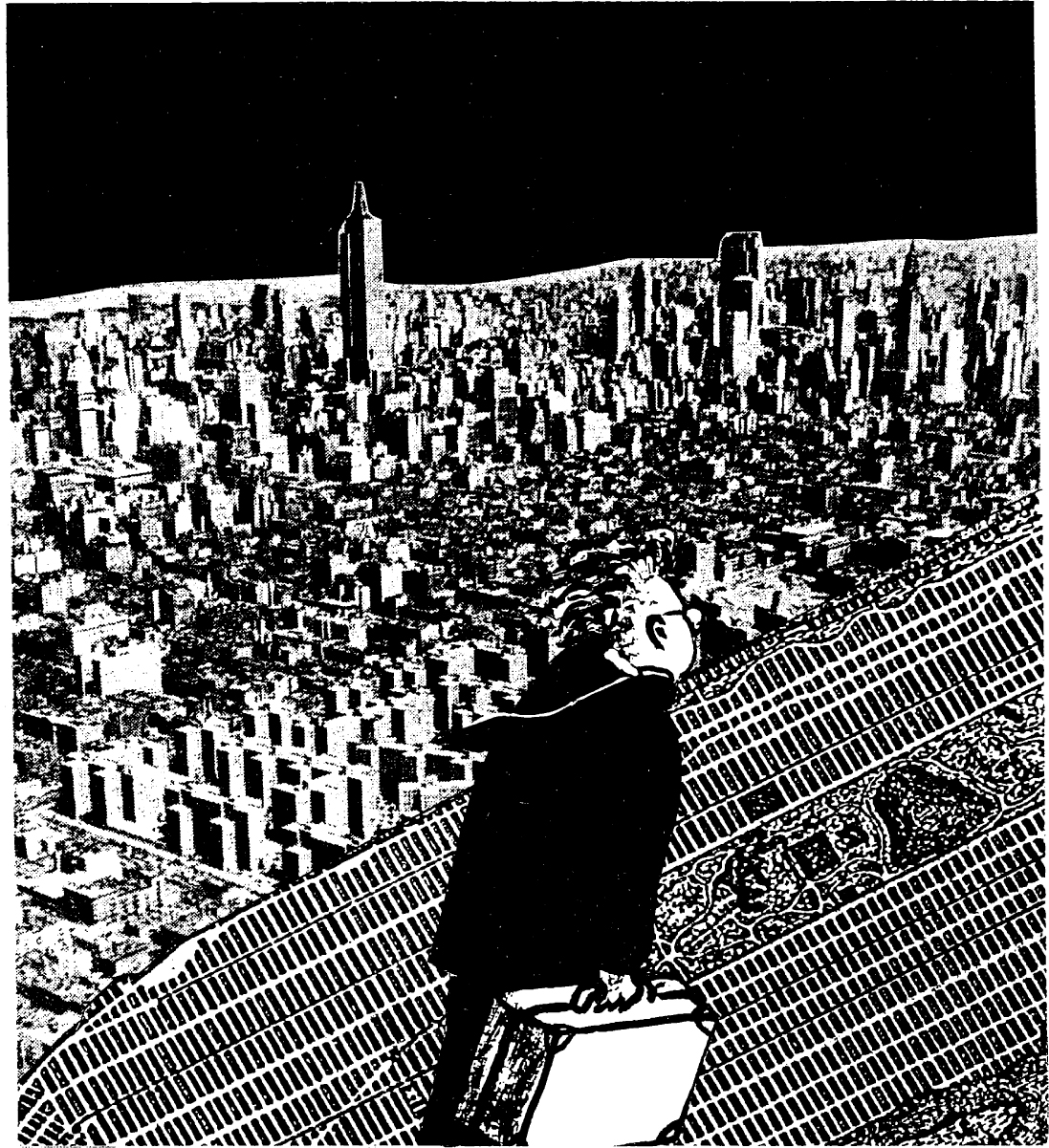

We are left to wonder if Benjamin ever meant to leave Europe. He would remain “in transit”, as perhaps he implies in a letter to Adorno, October 1938. “… every now and then, I glance at the city plan of New York that Brecht’s son Stefan has mounted on his wall and I walk up and down the long street on the Hudson where your house is.”

Something irreplaceable in European culture died with Walter Benjamin. Not the brilliance of a mind only, but a unique spirit, the passionate rescuer of a history in danger of extinction.

What does the critic truly seek? “Contemporary relevance”, as Benjamin announced in his plan for the abortive journal, Angelus Novus, in 1922. “… according to a legend in the Talmud, the angels – who are born anew every instant in countless numbers – are created in order to perish and to vanish into the void, once they have sung their hymn in the presence of God.”

True to his nature as an allegorist critic, Benjamin is a ruin. But what a ruin! “In the spirit of allegory, it is conceived from the outset as a ruin, a fragment. Others may shine resplendently as on the first day; this form preserves the image of beauty to the very last.”