Mark was fearless. Not a big guy, but in a courtroom he was a giant.

—A friend

Growing up in Dallas, Mark Hasse had what his older brother called a whip-smart mind. A scrawny kid who gobbled junk food and candy bars but never gained weight, he described himself in junior high as a “science geek,” one of his favorite stories the day he blew up the family’s screen door with a gunpowder experiment. “Mark was an arrogant little shit,” said Larry Cleghorn, who employed a teenage Mark. “He had girlfriends, but they got fed up. Mark could be cocky, and the girls got tired of it. He was a good kid, just really full of life.”

A natural, Mark earned a pilot’s license in high school. After graduating from Texas A&M University with a bachelor’s degree in history, he found a dream job, working for King Radio Corporation, an avionics manufacturer, flying its founder, Edward King Jr., in his private Cessna. Impressed with his young employee’s keen mind, King offered a slot on the corporation’s legal team if Mark went to law school.

Grabbing the opportunity, he enrolled at Southern Methodist University’s Dedman School of Law, where he devoured textbooks like Snickers bars. Friends later recalled how he read a book once and recited whole pages. “Mark was a polymath,” said Paula Sweeney, who met Mark at SMU in 1979. “He knew everything about everything, and he would tell you so.”

Yet people liked Mark. If he overflowed with confidence, he rarely took himself too seriously. Adept at accents and mannerisms, he mimicked professors, at times leading Sweeney to laugh so hard, her sides hurt. A persistent bachelor, Mark dated, but rarely seriously.

Although Mark envisioned law school as a route to a career in aviation, by the time he graduated, King had sold his company. Instead in the fall of 1981, Mark took a junior prosecutor’s job working for legendary Dallas district attorney Henry Wade, the man who charged Jack Ruby with the murder of President John F. Kennedy’s assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald.

Dressed like all Wade’s prosecutors in white shirts and dark suits, Mark wore cowboy boots to lengthen his slight five-foot-seven-inch, 140-pound frame. Starting out in misdemeanors, Mark learned quickly, transferring his swagger and flair to a hardnosed courtroom approach that led to quick promotions. Before long, he tried sex offenders and killers. Never shy, at trials he pointed at defendants, shouting out alleged offenses: “Murderer!”

Sex crimes and ones with children as victims magnified his fury. “When Mark got a burr under his saddle about a particular case, you prayed it wasn’t your client,” said Dallas attorney Colleen Dunbar. “He went after them with vengeance.”

Perhaps even then, Mark Hasse understood his job brought dangers. Dealing with hardened criminals, he must have considered that one day someone might not turn and walk away after a stinging defeat.

Whether or not Mark considered such consequences, his boss did. When he promoted Mark to head the office’s organized crime unit, Wade ordered Mark to become licensed as a volunteer deputy with a local constable’s office, to enable him to carry a gun into the courtroom. “Mark understood that there were truly evil people,” said his friend Marcus Busch. “At one point every prosecutor is threatened. You learn that life goes on and try not to think about it.”

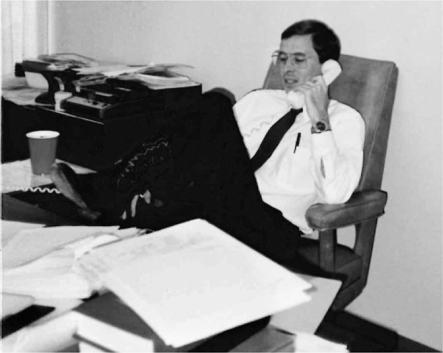

Mark in his office at the Dallas DA’s office, circa 1985

Courtesy of Marcus Busch

Rather than worried, Mark appeared exhilarated. With Busch and his other fellow prosecutors, Mark reveled in describing his courtroom exploits. In long accounts, he impersonated wise guys and gang members as he once had his law professors. “Mark loved telling stories, and he loved putting the bad guys away,” said a friend. “He wasn’t afraid of anything. Not anything.”

In 1988, eager to start his own practice, Mark left the Dallas DA’s office. Along with criminal law and personal injury suits, he specialized in a field close to his heart, aviation law. Over the years, he’d bought a plane and continued to fly, earning additional licenses as an airplane mechanic and inspector. Busch also a pilot, the two men frequented air shows and fantasized about grand adventures, flights around the oceans.

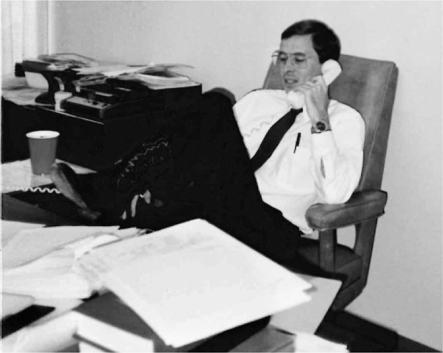

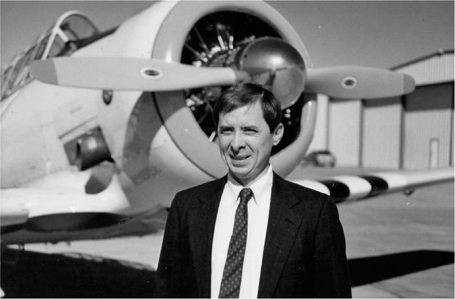

Mark Hasse in the mid-nineties

Courtesy of Morey Darznieks

While those dreams didn’t materialize, in 1995, Mark did depart on a grand quest, piloting a World War II aircraft, a single-engine, two-seater AT–6, in Freedom Flight America. A coast-to-coast caravan of vintage airplanes, the event marked the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the war. The day Mark lifted off from Ohio’s Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, he had no way of knowing how drastically his life would change. Over Luray, Virginia, in cloudy skies, the engine quit. Mark attempted to land in a field, but instead crashed into an embankment.

Helicoptered to the University of Virginia Medical School in Charlottesville, for days Mark hovered between life and death. When he awoke, doctors couldn’t predict the extent of his brain damage. His skull fractured and his left temporal lobe bruised, eventually it became evident that he’d lost much of his short-term memory. His sharp wit gone, Mark returned to Dallas, where Busch closed Mark’s office. “He wasn’t in any shape to practice law.”

For two years, Mark did little but concentrate on his recovery. He lived in his ranch house on acreage in Rockwall, east of Dallas, caring for a menagerie of stray dogs collected from the side of a road, and saw only family and close friends. His speech more deliberate, his reality had changed. With wire holding his broken skull together, never again would he ride the horses he boarded in his barn or scuba dive with friends. His wounds left scars on his chest and legs, a ragged five-inch one on his scalp, and a noticeable hollow on the left side of his forehead.

Slowly he recovered.

In 1997, Mark drove into the parking lot of Air Salvage, on the outskirts of the quiet Lancaster Airport, south of Dallas. Years earlier, he’d used the facility to store blown tires and other evidence for personal injury cases. Inside the modest and cluttered offices, Mark approached Alfred “Lucky” Louque, short and husky, a well-known airplane mechanic. They’d met years earlier, and Mark confided in Louque about his accident. “Brrrrr . . . brrrrr . . .” Mark sputtered, imitating the plane’s engine right before the crash.

“I wasn’t supposed to survive,” he said. Then he hesitated, thinking about what he’d say next. “Since I have, now that I have a second shot, I’m going to do things that make me happy.”

To Mark, that meant flying and working on airplanes. Before long, he’d purchased a hangar at the airport and started Intrepid Aircraft Sales, Inc. He bought planes, repaired then attempted to sell them. To Louque, Mark never looked more content than in oil-stained T-shirts and shorts tearing a plane apart, then piecing it back together.

Afternoons, Mark ended most days by walking over to Air Salvage, where he sat with Louque and another airplane mechanic, Curtis Mays, a tall, muscular man with a beard. Close friendships grew, as Mark entertained the men by recounting cases he’d handled, the worst-of-the-worst, during his days in the Dallas DA’s office. “Mark said he’d prosecuted somewhere between three and four hundred cases,” said Louque. “And he said he’d lost only one, a case where a guy claimed self-defense in an assault.”

Over the years, Mays and Louque agreed that Mark had a finely tuned sense of right and wrong. “He didn’t back down from anyone,” said Mays. “Mark was one of those red-white-and-blue guys who believed in the system.”

Years passed. Living frugally, Mark bought airplanes in need of repair, fixed them, and then listed them for sale. At one point, he owned four: a 1948 Luscombe, a high-winged monoplane, an experimental aircraft, and a Cessna. Despite the accident, Mark rarely looked happier than in the cockpit, especially flying low with the windows open, the wind on his face.

To Louque and Mays it appeared Mark made few sales. Yet Mark didn’t complain, any more than he did about the aches and pains he still suffered from the crash. More often he made fun of his situation, laughing about how the brain damage had resulted in the loss of his sense of smell. One afternoon at the airport, he stirred a pot of gumbo, not realizing it had turned rancid. When someone told him, he shrugged and said, “It’s a good thing I didn’t eat any.”

Despite not practicing law, Mark never formally relinquished his license. As the years passed, when he again felt capable, he did small jobs for friends, writing wills, advising on real estate transactions, reviewing contracts, but his focus remained on the airplanes.

The years Mark worked on his planes at the Lancaster Airport would be among the most content of his life. His brain healed, restoring his memory and his sense of humor. In time, the old Mark returned, the quick-witted lawyer who loved a good story.

In late 2009, Mark reflected in conversations with his friends about the possibility of restarting his legal career. While he loved repairing airplanes, he admitted it had proven a financial failure. With his medical history, he couldn’t find health insurance. And at fifty-four, Mark wanted a job with a pension. Considering possibilities, Mark settled on a slot with a DA’s office. Rather than Dallas with its big-city crime, he preferred a rural county. Along with money and insurance concerns, he told Louque that he’d missed “putting bad guys behind bars.”

Months later, Mark announced that he’d found just such a position in Kaufman County, where an old Dallas friend, Rick Harrison, was district attorney. “I think I’m going to play that gig for a while,” Mark told Louque. “I’ll be a prosecutor again. That’s what I’m good at.”

Certainly Kaufman was lucky to get Mark Hasse. He had all the right credentials, especially his years of prosecuting in a busy courtroom. His mind, if not as sharp as it had been before the accident, had recovered to the extent that no one doubted his abilities. “Mark was still one of the smartest people I knew,” said Marcus Busch.

In July 2010, Mark began work in Kaufman County, half an hour’s drive from his home in Rockwall. It must have seemed like the perfect match. His $74,000 salary came with health insurance and a pension. A predominantly rural county, Kaufman had little big crime, a murder or two a year, a couple of dozen assaults, some domestic violence. Instead, the cases involved meth labs; DWIs; public intoxication; stolen cars, cows, and horses; and dog bites.

In the old, rundown courthouse, Harrison assigned Mark the chief prosecutor’s position in the 422nd District Court, the one presided over by Judge Michael Chitty, and Mark settled into an office next to Brandi Fernandez, the office’s first assistant and the chief prosecutor in the county’s only other district court, Judge Tygrett’s Eighty-sixth.

Quickly, Mark’s life fell into a pattern.

In the mornings, he drove in from his ranch in Rockwall and parked on a side street behind Lott’s, a dry cleaner that had been on a corner across from the courthouse since 1959. Still so thin one friend said he resembled a greyhound, Mark stocked a desk drawer with junk food and his office refrigerator with Country Time lemonade. Word spread of his sweet tooth, and when items turned up missing from lunches, more often than not the owner sought out Mark.

Mark Hasse in his Kaufman County ID photo

Around the office, like a character in a beach movie, Mark stuck his head in offices and called the men “dude.” With the women, the lifelong bachelor bantered and indulged in practical jokes. When he told his assistant that he’d lost his sense of smell in the plane crash, she hid cheese in his office. Soon others complained of the stench, but not Mark. “Okay. What did you put in my office?” he asked after one attorney made a face and held her nose.

“Mark didn’t have a filter,” said Fernandez. “The women teased him about being skinny, and he teased them about being chunky. Somehow Mark always got the last word.”

On non-court days, he wore what many agreed ranked among the ugliest sweaters imaginable. “We thought his mother must have given them to him decades ago and he just kept wearing them,” said one of the secretaries. Perhaps because he had so little body fat, Mark felt perpetually chilled, so much so that he sported sweaters in the summer and in the winter long johns under his business suits.

In the afternoons, Mark, as he had for years at the airport, made the rounds, looking for an open door, landing in someone’s office, and then regaling them with stories of the bad old Dallas days when he’d taken down major criminals. “Once Mark walked in your office, you had to figure that you’d lost at least thirty-five minutes,” said one attorney with a laugh. “It wasn’t going to happen that he was going to let you get back to work.”

No one complained, however, because they appreciated the other Mark, the slight man who became a giant in the courtroom. There his stories became the facts of the cases, the evidence that, pieced together, formed pictures of horrible wrongs, ones he pleaded with juries to make right. “Mark could connect with jurors like few prosecutors I’d ever seen,” said one lawyer. His fellow lawyers saw Mark as fair, unless someone tried to manipulate him or had truly injured another. Then Mark became relentless.

In hindsight, Mark Hasse must have understood when he walked in the door at the Kaufman County DA’s office that first time that the office faced a potentially tumultuous transition. Three months before Mark started, Rick Harrison had been defeated in his bid for reelection by Mike McLelland. If Mark did any research, read any of Harrison’s ads or listened to office scuttlebutt, he knew how little criminal experience the incoming district attorney had. At times, Mark mused with the others about what it would all mean. Would the new DA understand the cases they prosecuted?

“You can’t learn criminal law by sitting in on a few trials,” Mark told one friend. “How’s this guy going to know what we’re up against? How’s he going to understand who should be prosecuted, and who shouldn’t?”