Eric was a planner. The reason he picked that Saturday was that he figured a lot of the deputies would be off for Easter. He based that on what he’d seen as a reserve deputy.

—Kim Williams

Heavy storms rocked Kaufman County that night and early the next morning. At 3 a.m. the skies crepitated over Forney, white-hot, jagged bands of lightning, pounding thunder that echoed through the darkness.

On Overlook, Kim wearily climbed out of bed at five to let the dogs out and feed them. Already up, Eric dressed in the outfit he’d modeled the night before. When Kim had their three Pomeranians diapered and back in their kennels, they walked out the door.

The drive to Gibson Self Storage felt excruciating to Kim. The storm brought with it wind, and although the rain finally stopped, gusts pummeled the Sport Trac. The gates at Gibson were accessible at six, and they arrived six minutes later. Eric pulled over and keyed in his code, 2072, and they entered as he always did from the far gate, the one near the Chicken Express drive-through.

The door on Unit 18 up, he drove out the white Crown Victoria. Kim got in the car’s passenger seat while he parked the Sport Trac inside the unit and lowered the door, locking it. In the car, Eric put blue surgical-type booties on his feet and wore latex gloves. They pulled out of Gibson’s at 6:18, turned right as they exited the gate, and headed east on U.S. 175 for the twenty-minute ride to Forney. As Eric drove, Kim slumped in the seat, drifting off on her medication.

At times, her eyes fluttered and she thought about where they were going and what Eric intended to do. “It’s Easter weekend. What if they have family there?” she asked.

“I’m going to do it anyway,” he answered. “If anyone else is there, I’ll kill them, too.”

When they got to the McLellands’ house, Eric parked in the driveway and got out, leaving the driver’s side door open behind him. The car’s dome light didn’t go on, and he’d turned the headlights off. She watched as he hurried toward the front door, an assault rifle hanging from the sling over his shoulder. A light went on in the left side of the house, in the bedroom where the McLellands slept. The porch light went on, and then Eric disappeared inside.

A second later, Kim heard the rat-a-tat-tat of gunfire. “Oh my God,” she thought. “Oh my God.” She waited, nervous, her stomach churning, her head throbbing. More gunfire. It seemed longer, but less than two minutes after he entered the house, Eric hurried toward the car. He opened the car’s back door and tossed the gun on the backseat, shut the door, got behind the wheel, and then backed out of the driveway. As he drove, he pulled off the helmet, throwing that, too, onto the backseat. Resolutely quiet, Eric looked nervous, until they pulled out of the neighborhood.

Once on their way, he smiled and laughed.

The route Eric took back to Gibson differed from the one he’d taken there, veering toward the north. On 1641 he turned left just before the Forney Community Park, with a playground and tennis courts. Kim didn’t ask about what had happened in the house, not wanting to know, but it seemed Eric wanted to talk.

“His wife didn’t die right away,” Eric said suddenly. “She was still moaning, so I put a bullet through her head.”

When he said it, Kim’s stomach roiled, but she thought Eric sounded proud.

In the Crown Vic, Eric took a right on I–20, then a left on Beltline Road. He used his code to open Gibson’s gate again at 7:07 a.m., forty-nine minutes after they’d driven out. At Unit 18, Eric backed the Sport Trac out. While she waited, he drove the Crown Vic back into the unit. Once he did, she pulled the door down but left a foot-high gap at the bottom. Then, just as after Mark Hasse’s murder, Kim heard Eric spray the car down, cleaning it, and he walked out in other clothes, blue jeans and a green shirt with Velcro slits on the side. “I didn’t think anything. I was just mostly scared,” she said. “Being around him. Getting caught. I was scared.”

Seventeen minutes after they returned to Gibson, they drove out the gate. On Overlook, they stopped at Kim’s parents’ house, dropping in to check on them. Later, at their own house, Eric logged onto his computer and turned on all the TVs, watching news reports.

“I’m going to lie down,” Kim said.

“Okay,” Eric said, appearing to barely notice her.

When she woke up, they returned to her parents’ house, and Eric, smiling and laughing, grilled steaks for all of them for dinner. By then, she’d put the morning’s horror behind her, relieved to have it over. So much so that she felt happy watching him celebrate.

At 8:30 that morning, Sam Keats picked up rose plants to bring to the McLellands’ house. She’d been invited for Easter the next day, and Cynthia wanted help planting the roses in the garden before everyone arrived. As she drove, Keats called Cynthia’s cell, but didn’t get an answer. She called again at 9 and 9:30. No answer. She left a message.

Wondering if Cynthia’s plans had changed, Sam called Leah.

The rain and thunder had roused Leah off and on during the night. She woke up early and went to the vegetable co-op to pick up her produce and Cynthia’s. When Keats called, Leah thought about Cynthia not answering her phone and assumed that she’d been called into work. That happened sometimes, and sometimes Cynthia simply forgot appointments. Neither Keats nor Leah worried.

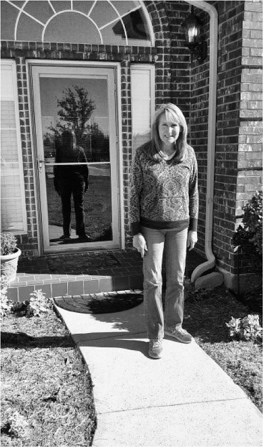

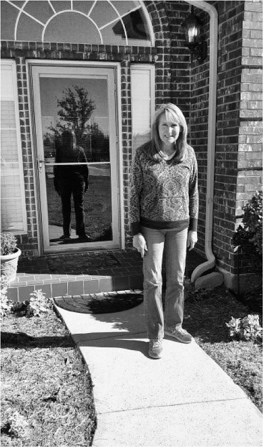

About eleven, Keats, with her dogs in the back of her pickup, drove to the McLelland house, thinking that she would deliver the roses. When she got there, the house looked strange. She rang the doorbell, and no one answered. At first, she couldn’t isolate what bothered her, but then she noticed the light on and the ceiling fan churning in the window on the left, Mike and Cynthia’s bedroom. That seemed odd. The newspaper lay in the wrapper on the driveway. Keats thought about walking in. The door was nearly always unlocked, but something told her not to try it.

Keats left, deciding to bring her dogs home. She drove a little, and then called Leah again. “Mike’s truck is there, and so is Cynthia’s car,” she said. “Something is wrong.”

Sam Keats on the McLellands’ front walk

Kathryn Casey

“Well, I’m supposed to bring their vegetables to them,” Leah said. “Maybe Mike went somewhere with someone.”

“Can you call them?” Keats asked. “They’ll answer the phone if you call them.”

Leah agreed, then put in calls to both Mike’s and Cynthia’s cell phones. They didn’t answer. At her house, she walked outside the front door and looked out at the sky and the grass. “That’s weird,” she thought. Considering the possibilities, she decided that maybe Mike and Cynthia had gone to a movie, and they’d turned their cell phones off.

Still, something bothered her. She called again. No answers. “Have you heard from your mom today?” she asked Nathan when she reached him later that afternoon.

“No,” he said. “I’ll call and see if someone else has heard from them.” He talked to Cynthia’s mother, her sister Nancy, and Christina. No one had talked to his mother or Mike. Nathan didn’t know that Mike’s mother, Wyvonne, had been calling off and on all morning and afternoon, too, without an answer. Again he tried his mother’s number, but she didn’t answer.

Leah sat in the rocking chair in the house when Nathan called back. “No one has talked to them. Can you go over there?”

“Okay,” Leah said. “I have their vegetables. I’ll run them over.”

After she loaded a crate of strawberries and a box of vegetables and fruit in her car, Leah drove toward Blarney Stone Way. At the house, she pulled into the driveway. Holding the crate of strawberries, she rang the doorbell. No one answered.

Walking around the house, she saw Mike’s truck, and then she noticed Cynthia’s car turned around and pointed down the driveway toward the street. Leah thought about how Mike habitually parked his wife’s car that way each night to make it easier for Cynthia to pull out onto the road. That meant Cynthia hadn’t taken her car out that day. That seemed odd. And the newspaper in the driveway bothered Leah. Cynthia loved reading the newspaper. Each morning she picked it up when she walked the dogs. That it remained outside didn’t seem right.

Leah had her key to the McLelland house. She knew that often the front door was unlocked. But she stood on the threshold still holding the crate of strawberries and stopped before grabbing the storm door handle. Behind it the heavy wooden front door blocked the view. Usually she would have walked right in shouting, “Cynthia! Mike!”

Instead she took the strawberries back to her car. Then she walked farther around the house. She checked the back door. Closed. She looked inside the cars. Nothing unusual. She heard Mike and Cynthia’s dogs barking in their crates. Feeling queasy, she returned to her car. She pulled out of the driveway thinking she’d get an iced tea. A short time later, her phone rang.

“Did you go to Mom’s?” Nathan asked.

“They aren’t there.”

“Did you go in?”

“No. I could hear the dogs in the crates. They must have gone somewhere.”

“Can you go back?” Nathan asked. “You have a key.”

She didn’t want to. “Only for you, Nathan,” she said. With that, she turned around and headed back to Blarney Stone, fighting an overwhelming sense of dread.

On the way, Leah called C.J., her oldest son. He and Skeet were working on a project they’d planned for weeks. “Something is wrong,” Skeet said, when C.J. repeated what Leah told him. “Call your mom and tell her not to go in the house. We’ll be there in a few minutes.”

When Skeet and C.J. arrived, they walked with Leah to the McLellands’ front door. Leah felt sick to her stomach as C.J. opened the screen door, then pounded on the wooden inner door and yelled, “Mike.” Again, without an answer.

As Leah watched, her oldest son grabbed the handle and pressed down on the lock. The door swung open. It was unlocked. C.J. stepped inside shouting, “Mike! Cynthia!”

Falling to her knees, Leah screamed.

When C.J. looked back, his mother pointed at the floor. Her voice suddenly hoarse, she said, “Your feet! There are shells between your feet!”

C.J. glanced down and saw spent casings on a beige throw rug between his feet. At that, C.J. took a few more steps forward and saw Cynthia on the floor, on top of an oriental rug in front of the fireplace, a pool of drying blood near her head. Immediately, he backed out of the house. Once he and Skeet had Leah upright, C.J. said, “I’m going to the car. I’m going to get my gun.”

By the time C.J. walked his mother back to the driveway and returned with his gun, Skeet had entered the house, going far enough inside to find Mike’s body sprawled on the floor in a small hallway.

Leah waited near the car, as her husband and son walked toward her. “Mom,” C.J. said. “I’m so sorry . . . They’ve been dead for a long time.”

Leah screamed slightly, just as Sam Keats drove back up to the house and got out of her truck. She saw the look on C.J.’s face, pale as if all the blood had been pulled from his body. She looked at Leah. “I knew it was bad.”

“They’re gone,” Leah said.