Someday, I tell my wife, when we’re older in the nursing home with blankets on our laps in the wheelchairs, we’ll look back at this, remember, and know life goes on. You have to go on.

—Judge Bruce Wood

On December 30, 2014, Eric Williams sat in a cell in the Texas Department of Corrections Polunsky Unit, on death row. Matt Seymour was off of his case, but Eric’s other attorneys prepared his appeal. His execution date hadn’t been set yet, and probably wouldn’t be for years to come, while his appeals worked through the courts. One of the issues they would cite was that scans showed Eric had signs of possible brain damage either from birth, due to injuries, or as a result of poorly controlled diabetes. The appeal contended among other things that had the jurors been presented with that evidence, they might have opted against the death penalty.

Inside the Kaufman County courthouse on that date, Kim pleaded guilty to murdering Mark Hasse, approximately one hundred feet away from the parking lot where he died. The yellow metal arches over the entrances had been cut off to prevent trucks from hitting them. Judge Wood had the one closest to where Mark died turned into a cross and painted white. Some complained that religious symbols shouldn’t be on county property, but others appreciated the monument to a painful time. Once in a while people still dropped off tributes, silk flowers and the like, that they placed nearby. Although it had been nearly two years, Kaufman hadn’t forgotten.

A 2016 photo of the cross marking where Mark Hasse died

Kathryn Casey

Others had memorialized the victims. In Kaufman’s courthouse, a quilted banner hung in the victim’s assistance room, one in Cynthia’s favorite pattern, log cabin, with hearts around the outside. In the center, the members of the quilters’ guild stitched the scales of justice, in her honor and Mike’s. Others erected a marble bench in her memory on the grounds of Terrell State Hospital, where she’d worked. And Mike’s and Mark’s names had been inscribed on the National Prosecutor Memorial in Columbia, South Carolina. They became the twelfth and thirteenth names on the monument. The oldest case dated back to William Foster, a Virginia prosecutor who died in a gun battle in 1912.

The decision had been made for Kim to plead on the Hasse case rather than the McLelland murders. Eric had been convicted on the McLelland killings, and this meant that someone took responsibility for Mark. The deal included a forty-year sentence, making Kim eligible for parole in 2033 at the age of sixty-six.

From the stand that day, Cynthia’s son, Nathan, told her that he felt relief not having to endure another trial, and that “these murders have torn apart my family and Mark Hasse’s family.” Rather than look down as Eric had during his victim impact, presumably to avoid looking his victims’ families in the eyes, Kim met Nathan’s gaze and nodded.

“At least she has a little conscience,” JR said. But he also told her that he held her responsible. “You had too many opportunities to stop it, and you didn’t take that.”

Later recalling Eric’s trial, all he and his family had endured, JR said, “When they came back with the death penalty against Eric, it felt like a letdown. I guess I thought it would make things feel like they’d changed. But they didn’t. It didn’t bring my dad back. It didn’t take the hurt away. The only good thing was that Eric Williams would never hurt anyone else.”

Thinking about all that had happened, he paused, then shook his head in disgust. “You know, this whole thing was basically small-town politics gone bad.”

When I talked with Matt Seymour, living by the rules governing attorneys, he said little about his representation of Eric, but one thing came through clearly. “I think the day they gave Eric the death penalty was among the worst in my life,” he said, his eyes clouded with tears. “I saw part of myself in Eric. And when the jury came back and said that he was to be put to death . . .”

At Toby Shook’s office on a Saturday morning, I met with Shook and Bill Wirskye. Both dressed for family day, planning to spend the time watching baseball, they looked happy and proud of the sentence, neither one voicing any qualms about the death penalty.

They did express one regret, that no one solved the cases before Cynthia’s and Mike’s murders. “We came tantalizingly close a few times,” Wirskye said. “But we just weren’t quite there.”

I’d heard after the trial that Kim and Eric had turned down all media inquiries, so I wasn’t hopeful. But as I always do, I put in requests for interviews. Their agreement, then, left me surprised but pleased.

“I’ve read one of your books,” Kim wrote to me. “. . . Yes, I’ll talk to you.”

Eric responded as well, sounding eager. Over the coming year and a half, I’d drive periodically to their prisons, showing up with my tape recorders, pens, notepads, and camera.

By the time I arrived for that first visit, I’d already heard a lot about Kim. Some had told me that they saw her as not a reluctant coconspirator, but perhaps the mastermind, someone who’d urged Eric to “get even and pull the trigger.” Some of Eric’s lawyer friends still didn’t see him as capable of the murders, but they had a more sinister view of Kim.

In contrast, most of the investigators viewed Kim as another victim, someone who’d fallen under Eric’s trance. As dependent as she’d been on Eric, Ranger Kasper wondered if perhaps Kim had Stockholm Syndrome, where hostages bond with their captors. “I did think she was genuinely frightened,” Bill Wirskye said. “But I thought she was cheerleading him, too.”

Kim Williams in prison, Gatesville, Texas, 2016

Kathryn Casey

I wasn’t sure what to think.

The woman I met in prison, however, appeared truly regretful. She talked often of her drug addictions during the final years she lived in the house on Overlook with Eric, describing it as a fog that anesthetized her to all that unfolded around her. And she fumed. “I couldn’t believe he did this, and that he insisted on including me. Why would he do that?”

In prison, Kim took only anti-inflammatories for her rheumatoid arthritis, and then not every day. But she looked well, fairly content. She smiled often, and she always seemed happy to see me. She asked about the outside world, and she looked wistful realizing she’d probably never again be part of it. More often than not, we spent part of our time together with her musing over Eric’s intentions. She talked of his intellect, his gifts, and she wondered why he’d do the things he did, sending in Crime Stoppers tips and the like. “Did he want to get caught?” she asked me one afternoon.

“No, I think his ego got the better of him,” I said, and she nodded.

In detail, she described the plans and the murders, and the uneasy feeling—despite the drugs—she had living with Eric. Yet in the same interviews, she repeated often that she’d loved him. “What he wanted, I wanted,” she said. “And I was mad at those people. Those two men ruined our lives.”

While I sensed sadness about her, it wasn’t until late in our second visit that she sobbed as she talked about Cynthia’s murder. “I think about it every day. I have the blood of three people on my hands. I try not to let people here see me cry, but at night, sometimes, I think about her. How frightened she must have been. And I think about what I did to their families. And my own family. And I’m sorry.”

For a long time, she didn’t ask me if I visited Eric as well, and I didn’t mention it. Then it came out, and one day, in a letter, she wrote: “What do you think about Eric?”

For months, I’d struggled with that same question.

Interestingly, many of those who tried to solve the mystery of Mark Hasse’s murder doubted Eric would have ever been caught if he’d stopped after that first killing. “I don’t think we would have found enough evidence,” said the sheriff with a shrug.

“Eric had all the criminal gods with him. He did it without being recognized. He executed and got away. He had the suckers at the guard who weren’t turning him in. He had Kim doped up. That must have been an ecstatic sixty days,” Erleigh Wiley told me. “And then he decided, it went so well, to kill Mike.”

But could Eric have stopped? I didn’t think so. I didn’t think his ego would have let him. How much better would it have been to get away with killing two or three people than one?

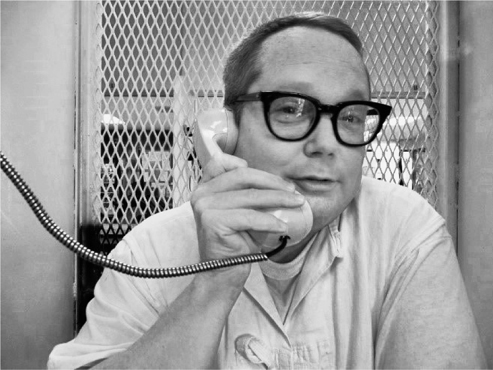

The Polunsky Unit, Texas’s death row, was an austere place, off-white walls, concrete and metal, gates and razor wire, guard towers and phone booth–size compartments to confine inmates while talking on telephones to visitors. The Eric Williams on the other side of the Plexiglas window appeared much as others described him. Eric wasn’t a big man or a muscular one. Rather than a triple killer, he looked like a computer programmer. When I arrived, he always smiled. He had a calm manner and a dry sense of humor. When I asked a question he deemed silly or strange, he had a crooked smile and dimples.

If I repeated a question, he sometimes appeared to lose patience with me, as if he talked to a child or someone whose intellect didn’t equal his.

Eric Williams in prison, 2016

Kathryn Casey

One Kaufman friend of Eric’s told me that, looking back, she wasn’t sure she ever knew him, although they’d been close for years. “Because he was our friend, we overlooked a lot of things. No one wanted to think he was that diabolical.”

“He doesn’t look like a killer, does he?” a prison employee said one day, as I walked from Eric’s unit. “Maybe that made him more dangerous?”

On my trips into Kaufman, I’d met a lot of Eric’s friends, who continued to believe that he’d been pushed too hard by Mike McLelland and Mark Hasse, and that he’d snapped. The guard members I interviewed talked of what happened to Eric as a trigger. “Everyone has one,” a guardsman told me. “There’s always something capable of setting a person off.”

In truth, there were days I shared that opinion. Ruining a life, taking away someone’s livelihood for $600 worth of monitors, especially when one sat on his county desk, did seem excessive. On one trip, I told Eric that, and he nodded. Yet, it didn’t matter in the wake of what he’d done. Nothing, after all, could account for assassinating three people. Nothing mitigated the malevolence of the murders.

While Kim talked in detail with me about their lives and the killings, Eric never admitted the murders. Instead, he talked in riddles. Suggesting the things in the storage unit weren’t his, one day he prodded: “Did it bother you that no one found the key to the storage unit in my things? If you find the person who has the key, you’ll find the killer.”

What he failed to take into account was that all the possessions in the unit tied to him. It reminded me of what Zach, Eric’s brother-in-law, told me, that Eric had asked him to pull a Sport Trac–size vehicle into a ten-by-twenty storage unit. “It was silly,” Zach said. “Of course, it fit.”

On a trip when I told Eric that I saw nothing to suggest he hadn’t committed the murders, he nodded at me. He didn’t frown, and he didn’t look surprised. As on so many of my other visits, he seemed emotionally detached, as if he’d expected it. Then we just continued talking, as if I hadn’t just said that I believed he’d murdered three people.

“Eric sent me a letter,” Kim told me on one of my visits. “He said he forgives me.”

“He forgives you?” I said. By then, Eric and I had written often, and he’d told me that he’d converted to Catholicism, and that he studied the Bible. At one point he sent me a page torn from a pamphlet, a profile of Saint Lucy, a patron saint to writers. I wrote and thanked him, posted it on my office wall. During lockdowns, when the prison guards scour through the cells and try to rid them of contraband, he didn’t respond to my letters, explaining that he spent the time meditating on his newfound faith.

Two aspects of Christianity, of course, are confession and repentance. So while I felt glad for Eric, that he’d found something to believe in, I did have nagging doubts. While I assumed he meant he forgave Kim for testifying against him, it seemed he had larger issues to address. “Shouldn’t he have asked you for forgiveness, for tying you up in all this?” I asked Kim. “Even more, what about the victims and their families?”

“Exactly,” she said. “Then he asked, ‘How am I?’ Really Eric? He’s not a stupid man. Certainly he realizes the toll this has taken on me and my family.” She thought about that and then she frowned and said, “Honestly, I don’t think he gives a thought to the three other people or their families. What he’s done. Everyone he’s hurt.”

In one of Eric’s many letters to me, he quoted Mother Teresa. “In the final analysis, it is between you and God,” he wrote. “It was never between you and them anyway.”

When I read that, I wondered if it was a way of telling me that he felt justified in all he’d done. In that same letter, he said that he could go “to the execution chamber tomorrow with a clear conscience.”

On one visit when he again insisted on his innocence, I asked if he knew who’d committed the murders. “I do.” But then when I asked who, so I could investigate any evidence he had, he refused to divulge a name but said, “The attorneys have all that information.”

“So there’s no one I can look at?” I said.

Eric shook his head. What he said next reminded me of a line out of a novel or a movie. “Take me completely out. Say it is unsolved. Unless that person’s DNA gets in the system. That’s the wild card.”

In the end, I decided that Eric Williams didn’t live in the soil-and-water physical world the rest of us inhabit, but in his imagination.

As I looked at all I’d learned, I believed part of Eric remained that kid who excelled in Dungeons & Dragons. Somehow the lines blurred between fantasy and reality. He bought the Segway after seeing one in a movie. He called Mark Hasse’s murder “Tombstone,” after his favorite Western. He dressed in costumes when he committed the murders, in the Hasse case not unlike a character out of a comic book wearing what looked like an executioner’s mask.

Perhaps that helped make him so dangerous. Since Mark Hasse, Mike and Cynthia McLelland, and their families weren’t real to him, he could never identify with them. He felt nothing but satisfaction when he killed them.

“Death row isn’t like what I would have expected,” he told me one day. “Not like in the movies. Most of the time, I’m simply alone.”

“Do you feel like you belong here at all?” I asked, after he said that while some of the pieces in the case did appear to point to him on the surface, he still thought the jurors should have had reasonable doubt.

“I believe God sent me here. Why, I don’t know,” he said.

We talked about what lay ahead if his appeals failed, his execution. At that he looked worried. He flushed and said he used to believe in the death penalty but didn’t any longer. “With a few exceptions I haven’t seen anyone here who needs to be executed.”

We talked more about the death penalty, and he shook his head. Then he said, “You know, in the end, it’s really all about revenge.”