Overview

In recent years, ethics scholarship has given increasing attention to the concept of moral imagination. Seeking to push ethics in a new direction, Johnson (1993) positioned the concept as a challenge to the Moral Law folk theory – the theory that moral reasoning involves the application of moral rules which tell us how to act. Johnson views the Moral Law folk theory as “radically at odds” (1993: 6) with what cognitive science has taught us about how human cognition actually works; he argues that moral reasoning as rule application can be effective only in non-controversial situations and leaves us unprepared to address more complex moral dilemmas. Drawing upon Dewey (1960), Johnson asserts that moral reasoning is “imaginative through and through” (1) and involves the application of intellectual principles. Rather than governing behavior as rules do, principles are summaries of our collective moral insight” (1993: 105) that “supply standpoints and methods” (105) which enable “imaginative exploration of the possibilities for constructive action within a present situation” (180).

Building upon the work of Johnson and others, Dr. Patricia Werhane has taken the lead in developing and applying the concept of moral imagination in the realm of business ethics. In her 1999 book Moral Imagination in Management Decision Making (MIMDM), Werhane addresses the question of why “ordinary, decent, intelligent managers engage in [ethically] questionable activities” (ix). She argues that self-interest, weak character, and a lack of moral awareness or moral development have limited ability to explain such behaviors, and she suggests a lack of moral imagination (MI) as a more powerful explanation. Werhane asserts that decision-makers are trapped in inherently incomplete and partial historically and socially embedded mental frameworks, typically regarding their organizational roles, which cause them to fail to account for particular moral concerns or even “consider simple norms of morality” (1999: 11).

As discussed below, MIMDM draws upon a wide range of philosophers to elaborate the concept of MI, explicates the relationship between moral reasoning and MI, and provides many examples of both exemplars and failures of MI. MIMDM and Werhane’s subsequent work on MI is practically synonymous with business ethics scholarship on the topic. It has spawned extensive scholarly efforts to further develop and apply the concept of MI within business ethics, more broadly within business scholarship, and even in fields far beyond business.

The purpose of this chapter is twofold. First, I review Werhane’s work on MI and discuss its impact. Here I refer to the many scholars who have built upon Werhane’s work, as well as to Werhane’s own efforts to further develop the concept of MI. A major thrust of this work has been to develop understanding of MI as an organizational and systems level concept. Second, I seek to build upon this work that treats MI as an organizational concept. I do so by applying Nonaka’s (1991) theory of the knowledge-creating company to explore the concept of the morally imaginative organization. Recognizing that leaders of organizations in complex, dynamic environments will be unable to anticipate, identify, and/or respond to the many moral dilemmas that their organizations enact (or fail to enact), I present a normative model in which moral imagination involves all organizational actors and is embedded into the organization’s strategically important knowledge-creating processes.

I proceed as follows. In the next section I briefly review Werhane’s seminal book MIMDM, and then in Section “Impact of MIMDM” I discuss the book’s impact in business ethics and beyond. Here I identify both works that apply Werhane’s insights and those which seek to develop those insights. I end this section by highlighting scholarship that seeks to understand MI as an organizational and systems-level concept. In Section “New Directions: The Morally Imaginative Organization” I then build on this work by taking a first step in developing the concept of the morally imaginative organization, as just mentioned. Finally, in Section “Conclusion” I call for further work that honor’s Werhane’s legacy by developing her insights into moral imagination.

Moral Imagination in Management Decision Making

As mentioned above, Werhane’s work on moral imagination has dominated business ethics scholarship on the topic. Werhane initiated the business ethics conversation on MI with a lecture titled Moral Imagination and the Search for Ethical Decision-Making, versions of which she presented at various universities in 1994 and 1995 (see for example Werhane 1994). Werhane followed these addresses with a 1998 article on MI in Business Ethics Quarterly and then her 1999 book MIMDM, which (like the article and lectures before it) traces morally questionable business practices to actors’ inability to escape their own historically and culturally situated mental models. Building on philosophers including Putnam, Rorty, and Wittgenstein as well as seminal work in social psychology, Werhane argues that because these mental models are largely taken for granted and inherently incomplete simplifications of reality, they limit actors’ ability to recognize the ethical issues at stake in a particular situation and imagine courses of action to address these issues. In Chapter 2 of MIMDM Werhane persuasively argues that unethical managerial behaviors often follow from managers’ limited mental models of their organizational roles – their understandings of what it means to be a manager, and how managers should manage.

Werhane then offers MI as a means of addressing this problem. She defines MI as “the ability in particular circumstances to discover and evaluate possibilities not merely determined by that circumstance, or limited by its operative mental models, or merely framed by a set of rules or rule-governed concerns" (93). Building on Kant’s definition of imagination, Werhane provides a processual definition of MI which includes three stages. The first of these, Werhane writes, is reproductive imagination. In this stage actors make sense of -- enact and interpret -- the particular situations and events in which they are engaged (Weick 1995), in the process becoming aware of their dominant mental models and how they shape their sensemaking. As their moral sentiments (Smith 1759) become engaged, Werhane explains, they begin “to understand the anguish and complexity in the dilemma at hand” (103) and become aware of the limits of their own understandings of the ethical issues at stake and how they should be addressed.

The second stage of MI, according to Werhane, is productive imagination, in which one assesses and challenges one’s own dominant mental models. Productive imagination involves “the move to a more general level” (121), a disengagement from the “narrative [of the situation at hand], from one’s roles and from a dominating conceptual scheme” (13). Werhane writes that productive imagination involves the ability to “challenge and evaluate [our] activities from [another] moral perspective, such as the perspective of common morality” (104). In discussing productive imagination, Werhane develops the idea that although individuals cannot disentangle their understandings of themselves from their roles and relationships, nor should they be reduced to them. Here Werhane builds upon Smith’s idea of the “impartial spectator” (1759); she argues that the productive imagination is triggered by one’s internal morally responsible agent that endures even as one’s roles and relationships change.

Finally, the third stage in Werhane’s model of MI is free reflection. Free reflection enables one to “…envision and actualize novel, morally justifiable possibilities” to answer moral questions. (105). These possibilities are not “parochially embedded in a restricted context [nor] confined by a certain point of view.” (12) Rather, Werhane writes, free reflection involves the ability to escape one own’s mental models, critique them as well as those of other actors, and imagine novel courses of action.

Werhane emphasizes that in her conception, MI involves movement between the particular and the general. The morally imaginative actor starts by paying close attention to the details of the situation, then disengages and scrutinizes those particulars and ways of understanding them, and then returns to the situation to address it. Here Werhane builds upon the work of Nussbaum, who presents MI as involving a dialogue between “a fine-tuned perception of particulars and a rule-governed concern for general obligations” (1990: 157). While Werhane’s explication of MI is theoretically grounded in philosophy and social psychology, MIMDM is full of real-world examples, both of MI and of failures to exercise it.

Impact of MIMDM

MIMDM represented a major step forward in the business ethics conversation because it presented a new view of how managers do and should enact and address ethical issues in business. Prior to the book (and still today), business ethics scholars tend to conceptualize ethical business decision making as rule application (see for instance Bowie’s (1999) Kantian perspective, and the virtue perspectives of Hartman (2015) and Solomon (2003)). In addition to claiming an important role for imagination in ethical decision making, MIMDM also provides a pragmatic and social constructivist perspective that had been missing from the literature.

A. Applications of MIMDM

Not surprisingly, then, MIMDM has been widely cited and employed, both in business ethics and beyond.1 Scholars in fields as diverse as ethics engineering (e.g., Harris et al. 2013), peace and conflict studies (Lederach 2005), human rights (Santoro 2003), public service (Lewis and Gilman 2005), media ethics (Patterson and Wilkins 1998), and even genetic psychology (Jordan 2007) have drawn upon MIMDM in addressing the ethical issues in their fields.

Of course, MIMDM has had its biggest impact on business scholarship. While some of this work has fallen quite far afield (see for example Drumright and Murphy’s (2004) paper on the lack of moral imagination in the advertising profession), MIMDM’s greatest influence has been felt in management scholarship. In the related areas of stakeholder management and leadership, important references to and applications of MIMDM have been made by Freeman et al. (2007), who view moral imagination as an important element of ethical leadership; Pless and Maak, in their 2012 book on responsible leadership (see also Maak and Pless (2006)); Waddock (2007), who examines the role of leadership (and the importance of MI) in addressing the gap between knowledge “haves” and “have nots”; Phillips (2003), in his article on the role of legitimacy in stakeholder management; and Conger and Riggio’s (2012) book on developing new leaders.

MIMDM also has made great purchase in business ethics. For example, Ashforth, Gioia, Robinson, and Treviño build upon MIMDM in their introductory article to Academy of Management Review’s 2008 special issue on organizational corruption; Sonenshein (2007) cites MIMDM in developing his model of ethical sensemaking in organizations; and Buchholz and Rosenthal (2005) argue that “the spirit of entrepreneurship” demands a moral decision making approach which emphasizes experimentation and the application of MI. Werhane herself has effectively applied the concept of MI to address pressing issues in business ethics. Most notably, with Michael Gorman (Werhane and Gorman 2005) she applies MI to analyze the intellectual property rights of pharmaceutical companies; and with numerous other colleagues she analyzes the results of Milgram’s famous Obedience experiment, suggesting that MI is needed to address the problem of obedience (Werhane et al. 2011).

Werhane’s conception of MI as presented in MIMDM also has been mobilized by numerous scholars who address building ethical organizations. These include Jason Stansbury (2009), who argues that ethical decision-making in organizations should be guided by the principles of discourse ethics; Stansbury and Barry (2007), who address the tension between organizational control and employee innovation in corporate ethics programs; Christensen and Kohls (2003), who present a framework for ethical decision-making during times of crisis; Verhezen, who argues for the importance of “visualizing and imagining ideals of goodness” in building organizational cultures of integrity (2010: 197); Whetstone (2001), who relates moral imagination to the establishment of virtue in organizations; and De Colle and Werhane (2008), who propose that ethical behavior in corporations would be increased if corporate ethics programs were designed with moral imagination in mind. Collectively, these papers draw upon MIMDM to insist that moral imagination both stimulates and is stimulated by ethical organizational cultures.

B. Development of the Concept of MI

In addition to shedding insights into particular business ethics and management issues and phenomena, the lessons of MIMDM also have spawned efforts (including Werhane’s own) to further develop the concept of MI. Moberg and Seabright (2000) re-formulate Werhane’s processual definition of MI in terms of Rest’s four-stage model of ethical decision making (sensitivity, judgment, intention, behavior); elaborating Werhane, they conclude that MI involves not only moral sensitivity but also “keen judgment, impassioned intent, and skillful implementation.” (874) Taking a neo-pragmatist approach, Gold (2011) re-conceptualizes MI as involving building consent among different linguistic communities. Moberg and Caldwell (2007) are more interested in identifying contextual factors which stimulate MI; through a clever manipulation of a business simulation involving MBA students, they find that organizational cultures “which have a salient ethics theme” (193) activate MI, but that the effect of culture on MI is smaller for individuals with strong moral identities. Hargrave (2012) focuses on the behavioral component of MI and how it is shaped by context. He identifies six approaches to MI -- creation, coercion, compromise, coalition, consent, and collaboration, each appropriate under particular structural conditions within the organization.

Intractable problems are “not created by, nor, by implication, solvable by an individual ethical actor even with the tools of moral or financial reasoning or even with the help of individual moral imagination…. The resolution [of these problems] has to take place through the tool of systems thinking, and a more systemic approach to moral imagination.” (34)

As the last sentence of the preceding quote indicates, Werhane’s 2002 paper identifies two new research avenues for MI scholarship: One exploring how individual actors can make sense of the complex systems in which the ethical problems they face are embedded; and another exploring how the actors who constitute complex systems collectively come to make sense of and address shared ethical issues. In the first, “individual moral imagination” stream, “systems thinking” refers to an individual thinking about a system. In the second, “collective moral imagination” stream (implied by the phrase “a more systemic approach to moral imagination”), “systems thinking” refers to a “thinking” social system. It is this second type of moral imagination which is the subject of the rest of this paper.

Werhane begins to build the concept of collective moral imagination in her 2002 paper when she writes that “a political economy can be trapped in its vision of itself and the world in ways that preclude change on [a] more systemic level” (2002: 39). She further develops this idea of systems-level MI in her 2008 paper in Journal of Business Ethics, which provides a short study of Exxon Mobil’s Chad-Cameroon project. In this project, Exxon Mobil established an alliance with the World Bank, the host governments of Chad and Cameroon, numerous nongovernmental organizations, and affected indigenous populations. This alliance developed and implemented innovative approaches to the many complex social and environmental issues associated with the project. These approaches included protections for the natural environment and the rights of indigenous people, a revenue sharing agreement that directed project revenues towards socially and environmentally beneficial uses, the establishment of a micro lending bank for local businesses, and the construction of new schools and medical facilities. Although the project has fallen short of expectations in numerous ways, it nevertheless provides a model of project development that incorporates moral imagination into its design and implementation. Werhane concludes that Exxon’s Mobil’s approach to the project was “holistic, envisioning the company as part of an alliance that takes into account and is responsible to multiple stakeholders, not merely shareholders and oil consumers” (2008: 470–71).

Hargrave (2009) also studies the Exxon Mobil Chad-Cameroon project to further develop the concept of systems-level collective moral imagination. He argues that “moral outcomes are not produced by individual actors alone but rather emerge from collective action processes [that] are influenced by political conditions and involve political behaviors that include issue framing and resource mobilization.” (85) Hargrave extends Werhane’s insight that morally imaginative actions can be produced by systems of actors by detailing the collective action processes from which the morally imaginative features of the Chad-Cameroon project were produced. Hargrave characterizes these as “pluralistic processes in which multiple actors with opposing moral viewpoints interact, and no single actor is in control” (88), and he notes that the project’s morally imaginative policies and programs “bore no resemblance to the arrangements that any of the project participants initially envisioned” (95).

Whereas Hargrave (2009) is concerned with social processes of moral imagination, Calton et al. (2013) seek to bring specificity and precision to understanding of the social structure of collective moral imagination. Their contention is that creating wealth at the base of the pyramid requires the application of moral imagination to establish communities of practice which produce situated learning and successful partnerships. Calton and colleagues identify three types of such communities of practice: decentered stakeholder networks, in which the firm of interest is placed as one of many participants in a global system; global action networks that bring together business, government, and civil society organizations with often opposing goals to address issues of shared concern; and “faces and places” communities which focus on developing context-specific, non-replicable practices to address social and environmental issues at the base of the pyramid. By showing that systems-level moral imagination can and should take different forms under different conditions, Calton and colleagues illustrate Werhane’s insight that moral imagination involves an integration of general ethical principles with a deep knowledge of contextual particulars.

One of the first (and best) efforts to develop understanding of collective moral imagination comes from Arnold and Hartman (2003), who detail the efforts of managers at Nike and adidas-Solomon (now Adidas) to change their companies’ supply chain policies and practices so that they are more responsive to a range of labor issues. An important insight of Arnold and Hartman’s paper is that in addition to taking context-specific actions, managers at the two shoe companies established structures and processes which facilitated individual and collective moral imagination at multiple levels both within and outside the two companies.

With respect to adidas-Solomon, Arnold and Hartman note that while efforts to reform the company’s supply chain started with the initiative of the general counsel of the company’s North American unit, Susheela Jayapal, many plant level managers and other employees “were empowered to evaluate the practices of contract factories in order to determine whether labor practices at those factories were consistent with respect for workers’ rights and to be creative and effective in their responses where they were not.” (452) Further, these actors created organizational policies and programs that enabled ongoing morally imaginative decision making. For example, Jayapal spearheaded the development and approval of new Standards of Engagement with suppliers, and the company established partnerships with industry competitors and nongovernmental organizations such as Save the Children. Arnold and Hartman make clear that while leadership initiated processes of change within their companies, ongoing ethical supply chain management became increasingly possible at the two companies because internal decision structures and policies and programs which encourage morally imaginative solutions were institutionalized – and because these corporate initiatives brought the companies into partnership with many external stakeholders.

In sum, the years since the publication of MIMDM have seen a wide application and extension of Werhane’s work on MI. Scholars – most notably Werhane herself – have significantly expanded upon the concept of moral imagination as presented in MIMDM. In addition to refining understanding of individual moral imagination, these scholars have begun to develop the idea that moral imagination also functions at the organizational and higher levels of organization. The timing of these intellectual developments is not coincidental; rather, they capture the zeitgeist of their time. Werhane and her followers have recognized that in a business environment marked by increasing complexity and rapid change, ethical decision-making needed to be reconceptualized as an imaginative, collective process.

New Directions: The Morally Imaginative Organization

A. The Received Model of Organizational MI

In this section I seek to further develop a model of organizational moral imagination. To do so, I begin by reviewing and analyzing the received model in the MI literature.

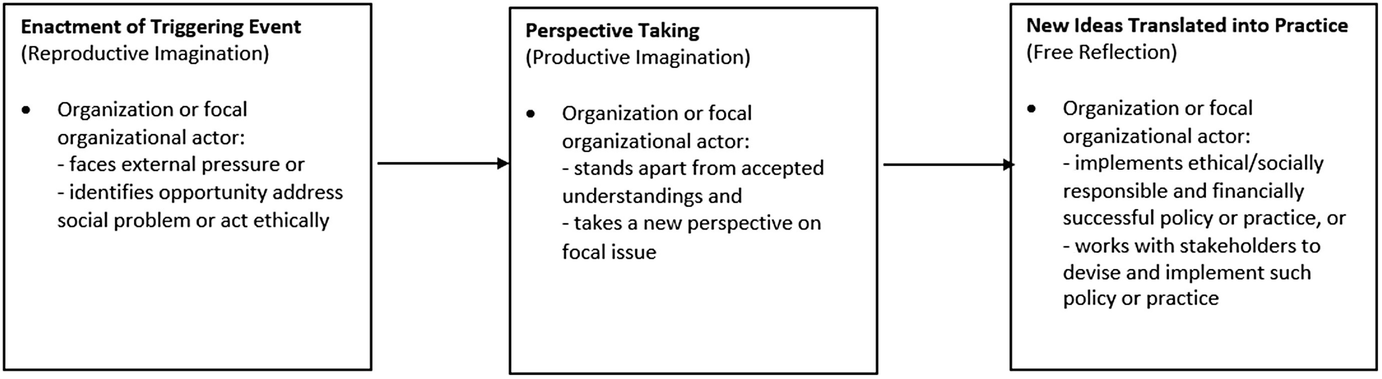

Analysis of the case studies found in the existing literature reveals a dominant (yet implicit) model of how Werhane’s three-step process of MI plays out at the organizational level. In the first step of this dominant model, reproductive imagination is represented as the enactment of a triggering event by an organization or leading organizational actor. The triggering event typically is enacted by the focal actor as an ethical dilemma or external pressure to act ethically, such as when CEO James Burke of Johnson & Johnson had to address incidents of poisoning associated with the company’s Tylenol capsules (Werhane 1998, 1999), or when Nike and Adidas were criticized by activists for the working conditions in their suppliers’ factories (Arnold and Hartman 2003). However, in some cases the triggering event is a focal actor’s perception that a social problem presents an opportunity, as when Mohammed Yunus saw the institutional void around poverty in Bangladesh as calling out for a private sector solution (Werhane 2002).

In the next step of the dominant model of organizational MI that I have derived from the literature, productive imagination occurs when the focal organization or actor responding to the triggering event stands outside of dominant understandings of the issue at hand and takes a different perspective on it. Often this perspective-taking is enabled by a supportive organizational culture and history. Werhane provides an example in MIMDM when she documents entrepreneur Ronald Grzywinski’s investment in and turnaround of South Shore Bank. Although the South Shore neighborhood was declining economically and the bank continued to operate in the neighborhood only because it was prohibited by statute from closing or moving, Grzywinski was able to imagine an approach to banking that would both earn a profit and help revitalize the declining neighborhood. Werhane’s 2008 paper provides another example of productive imagination. Here she shows that in response to public pressure to address poor working conditions in its supply chain, Nike “began to ‘look in the mirror’ at its mission [and] corporate image, and challenged itself to think about extending the scope of its responsibilities” (Werhane 2008: 469).

In the final step of the received model, the organization or leading actor engages in free reflection when translating ideas developed through productive imagination into practice. She does so either by taking actions that are both financially and ethically successful, or by collaborating with stakeholders to devise and implement ethically sound, innovative policies and practices. Taking such morally imaginative action often involves courage, risk-taking, and skill at reconciling tensions between competing objectives and interests. Burke of Johnson & Johnson made his widely heralded decision to pull Tylenol from store shelves despite advice from legal counsel and the FBI that he should not do so, and Grzyzwinski accomplished his goal of profitably operating a bank in South Shore when nobody else would by revamping South Shore’s credit assessment practices and pioneering the concept of development deposits (Werhane 1999.) Among other actions it took to address labor issues in its supply chain, Nike worked with local suppliers and the national Ministry of Education to establish a degree-granting educational program for its Vietnamese workers (Arnold and Hartman 2003.)

Received model of organizational moral imagination

Cases of organizational moral imagination

Case (Source) | Enactment of Triggering Event (Reproductive Imagination) | Perspective Taking (Productive Imagination) | New Ideas Translated into Practice (Free Reflection) |

|---|---|---|---|

Malden Mills (Werhane 1999) | Factory partially burns, causing significant job loss. | Based on history and culture of company, CEO prioritizes responsibilities to workers. | CEO decides to rebuild factory despite insufficient insurance coverage. |

Company continues to pay workers while factory is being rebuilt. Factory operating again within three months. | |||

Johnson & Johnson (Werhane 1999) | Poisoning incidents involving Tylenol capsules. | CEO cites corporate credo, which emphasizes responsibility to doctors, nurses, patients, and mothers. | CEO and top managers withdraw capsules from the market against advice, and despite loss of market share and lack of connection between manufacture and poisoning. Company eventually recaptures market share. |

Levi Strauss (Werhane 1999) | CEO is concerned with human rights and worker protections of employees in China. | CEO reflects upon the company’s code of ethics and expresses concern about legitimizing unethical practices and supporting governments. | CEO decides to withdraw from marketing, manufacturing, selling, and procuring raw materials from China. |

Merck (Werhane 1999) | Senior researcher recognizes that antiparasitic drug could be adapted to address river blindness. | Senior researcher and head of research find that market for new drug is insufficient, that development agencies will not provide financial contribution. Researchers “break out” of financial mindset, recognize responsibility “to the people”. | Company funds drug testing itself, decides to give drug away, builds distribution partnership with development agencies. |

South shore Bank (Werhane 1999) | Entrepreneur recognizes that bank in poor, underserved neighborhood is experiencing financial problems | Seeing opportunity to earn profit and contribute to neighborhood development, entrepreneur invests in company | Company establishes many “win-win” initiatives, including building restoration, minority business lending, and development deposits. |

Eskom (Werhane 2002) | South Africa’s national electricity company comes under scrutiny during anti-apartheid movement. | The company becomes aware of itself as an all-white company with a narrow view of service commitments, re- evaluates it mission, develops a new mental model of what it should be. | The company revises mission to include national electrification, experiments with new ways of providing electricity to the rural poor, employs non-white workers in supervisory roles. This catalyzes political reform. |

Grameen Bank (Werhane 2002) | Economist recognizes great poverty in Bangladesh, that the poor lack capital and property. | Contradicting typical banking logic, the economist starts a bank to make small loans to the poor. | The bank makes loans to over two million people, 97% women, in over 40 thousand villages. Default rate is low. Bank expands into other businesses that serve the poor, provides a banking model that is emulated around the world. |

Nike (Arnold and Hartman 2003) | The company comes under media and activist pressure for wage and human rights violations in the production of its products. | The CEO accepts responsibility for labor practices at its suppliers. | The CEO/company announces new initiatives related to supplier labor practices. These include a higher minimum wage, micro-enterprise loans for workers, supplier monitoring, and an education partnership with the Vietnamese government. |

Adidas-Solomon (Arnold and Hartman 2003) | The company comes under media and activist pressure for wage and human rights violations in the production of its products. | The company recognizes that a high level of control of suppliers comes with greater responsibility for suppliers’ working conditions. | Senior manager establishes new supplier standards of engagement that address wages, working conditions, and other issues. Company collaborates with competitors, industry associations to develop industry wide program to address child labor. |

Adidas-Solomon – Child labor in Vietnam (Arnold and Hartman 2003) | Corporate sustainability staff become aware of local problems | CEO commitment | Staff issues directive to contractors. Company expands stakeholder network to include NGO. Company and NGO develop approach that becomes company standard. |

Nike (Werhane 2008) | The company comes under media and activist pressure for wage and human rights violations in the production of its products | Company rethinks its mission and images, challenges itself to extend the scope of its responsibilities. | Company changes its mission and code of conduct, supplier standards; begins to establish alliances with suppliers to improve working conditions. |

Exxon Mobil Chad-Cameroon project (Werhane 2008) | The company recognizes the human rights and business risks associated with undertaking a project in a poor and corrupt country. | Company recognizes the need to address stakeholder concerns, that conventional model of project development will be ineffective. | Company forms a multi-stakeholder alliance, which makes many economically, socially, and environmentally beneficial project modifications. |

Exxon Mobil Chad-Cameroon project (Hargrave 2009) | As a result of activist criticism and based on past experience, the company recognizes the political, social, and environmental risks associated with undertaking a project in a poor and corrupt country. | Company recognizes the need to address stakeholder concerns, that conventional model of project development will be ineffective. | The company invites a multilateral organization (the World Bank) into the project to address stakeholder concerns and negotiate with host governments. The project is revised to include many economically, socially, and environmentally beneficial project modifications. |

B. A New Model of Organizational MI

The received model just presented captures important elements of organizational MI. Like any model, however, it features particular elements while ignoring or backgrounding others. In this case it appears that the received model treats the organization as a “black box”, saying very little about particular organizational actors and the actions they take. The case studies depict organizational MI as primarily involving either a managerial choice by an organizational leader, as in cases such as Johnson & Johnson (Werhane 1999) and Grameen Bank (Werhane 2002); or a set of decisions and actions taken by “the organization”, where little or no mention is made of the particular individuals and organizational units involved. This is true for example of the studies of the Chad-Cameroon oil projects by Werhane (2008) and Hargrave (2009). The only article of which we are aware which details actors and processes in a more fine-grained manner is Arnold and Hartman’s (2003) study of moral imagination at Nike and Adidas-Solomon.

This perhaps unintended depiction of moral imagination as involving only senior leaders – or no people at all – is out of step with recent developments in organization theory and the realities that modern complex organizations face. In recent decades organization theorists including Senge (2006), Weick (1995; Weick and Sutcliffe, 2006), and Nonaka (1991) have identified new models of organizing which facilitate adaptation to environmental uncertainty. Because of the complexity and rapid pace of change in their external environments, organizations have moved away from bureaucracy and “mechanistic” approaches to organizing in favor of more “organic” approaches (Burns and Stalker 1961). In organic organizations there are relatively few management layers, workers are empowered to make decisions, communication is dense, decisions often are made in teams, frequently cross-functional ones, and external stakeholders are consulted.

This shift in understanding of organizing suggests the need for a more distributed, team-oriented, and emergent conception of organizational moral imagination. If organizations are to continuously address moral dilemmas imaginatively in a complex and rapidly changing environment, then they must be designed to incorporate structures, policies, and practices which stimulate organizational actors to individually and collaboratively overcome mental biases, identify new perspectives, and envision and actualize new ideas and solutions to ethical dilemmas.

C. The Knowledge-Creating Company

In response to this challenge, I now sketch the outlines of a normative model of the morally imaginative organization. In doing so I draw upon one of the seminal models of the organic organization, Nonaka’s knowledge-creating company (1991). I first describe Nonaka’s model and then re-imagine it as infused with moral imagination.

The chief insight of Nonaka’s work is that in an increasingly complex and dynamic business environment, firms will be able to sustain a competitive advantage only if they continuously create and transfer knowledge (Nonaka 1991; Nonaka and Takeuchi 1995). Firms that do not constantly gather information and challenge and revise their prevailing mental models and practices will fail to develop the new processes and products that they will need to win customers and beat their competitors.

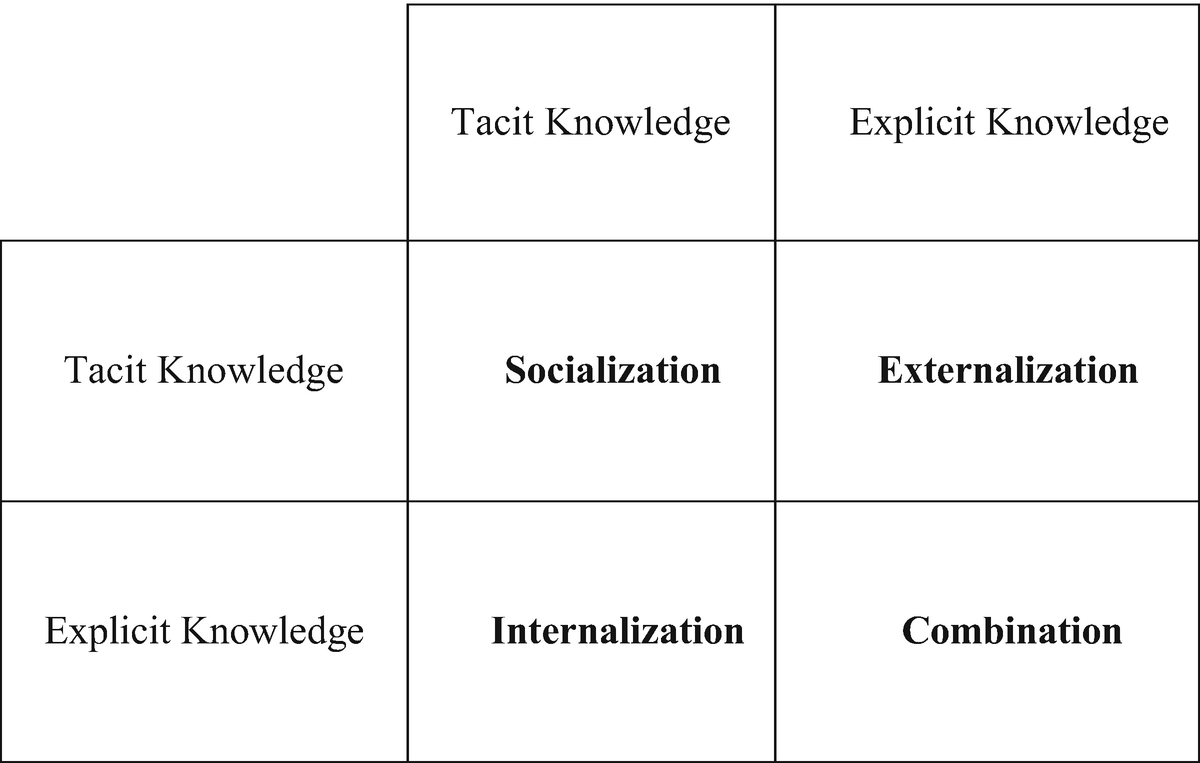

Nonaka builds upon the distinction between explicit and tacit knowledge (Polanyi 1958) to develop a thorough, prescriptive account of organizational knowledge creation and transfer processes. Explicit knowledge is formal and systematic, and can be easily communicated and shared; it is contained in organizational elements such as standard operating procedures and job descriptions. In contrast, tacit knowledge is personally held, and difficult to formalize and communicate to others. The actor may hold tacit knowledge in muscle memory (McKenzie and Potter 2004) and not even be aware that he holds it. Nonaka writes that tacit knowledge Is “deeply rooted in action and in an individual’s commitment to a specific context” (1991: 4).

- 1.

Socialization, in which individuals transfer tacit knowledge directly with others through practices which enable the sharing of experiences, such as observation, imitation, mentoring, and apprenticeship.

- 2.

Externalization, in which tacit knowledge is converted to explicit knowledge. Nonaka and Takeuchi refer to externalization as “finding a way to express the inexpressible” (1995: 44). Externalization involves the articulation and documentation of tacit knowledge so that it may be shared with others in the organization.

- 3.

Combination, which involves the creation of new explicit knowledge through the integration of different bodies of “explicit knowledge into a new whole” (1991: 4). Nonaka illustrates combination by referring to the example of a financial officer synthesizing financial information collected from throughout a company into a report that provides a picture of the financial health of the company as a whole.

- 4.

Internalization. Finally, once a new body of knowledge has been created through combination, it must be converted into tacit knowledge so that employees may embody it and act upon it. This occurs through training programs, simulations, and other tools that enable employees to incorporate the new explicit knowledge into their existing tacit knowledge bases. Once they have done so they can share this knowledge through socialization processes, as the knowledge spiral continues.

Nonaka and colleagues describe the organizational structure of the SECI process, delineating distinct roles for top management, middle managers, and frontline employees. A chief role of top managers is to create an organizational climate that promotes continuous learning, and to contribute to the SECI process by “articulating the company’s ‘conceptual umbrella’: the grand concepts that in highly universal and abstract terms identify the common features linking seemingly disparate activities or businesses into a coherent whole” (1991: 8). These concepts include a “knowledge vision”, a “driving objective” (Nonaka and Toyama 2005), and figurative expressions such as metaphors (Nonaka 1991). These act as guiding principles that employees can intuitively understand and apply as they engage in the knowledge creation process.

Another crucial task of top management in the knowledge cycle is to establish ba, which is a “shared space for emerging relationships” that “provides a platform for advancing individual and/or collective knowledge” (Nonaka and Konno 1998: 40). Ba provides the space in which teams create and transfer knowledge, and a different form of ba is associated with each stage in the knowledge spiral. For example, in the combination stage of the knowledge spiral, team members engage in dialogue and debate that centers around shared data. Nonaka writes that “teams play a central role in the knowledge-creating company because they provide a shared context where individuals can interact with each other and engage in the constant dialogue on which effective reflection depends” (1991: 9).

Nonaka and colleagues also accord an important role to middle managers in the knowledge cycle. It is their job to translate the tacit knowledge of the frontline workers below them into explicit knowledge (externalization). In addition, middle managers lead the process of combining various bodies of explicit knowledge, including the conceptual umbrella established by top management, into new, richer bodies of knowledge. They do so by building ba and leading dialogues. Nonaka and Toyama write that the management of the knowledge spiral requires managers to synthesize contradictions (Nonaka and Toyama 2002), run experiments, and even engage in Machiavellian politics to support knowledge creation and transfer (Nonaka and Toyama 2007). In short, middle managers play a crucial role in knowledge creation, serving “as a bridge between the visionary ideals of the top and the often chaotic market reality of those on the front line of the business” (Nonaka 1991: 9).

For their part, frontline employees contribute to the knowledge cycle through both internalization and socialization, continuously challenging and revising their understandings and practices, sharing their tacit knowledge, and working with middle management to externalize this knowledge.

D. MI and the Knowledge-Creating Company: The Morally Imaginative Organization

Integration of moral imagination theory into the theory of the knowledge-creating company suggests a new prescriptive model of the morally imaginative organization (MIO). A MIO is an organization that is able to effectively address the ethical challenges raised by environmental uncertainty because moral imagination has been distributed throughout and embedded into the organization’s strategically important knowledge-creating processes.

Because of their common conceptual foundation, MI theory and KCC theory are suitable for theoretical integration. Both depict processes in which actors move from the particular to the general and back again, creating knowledge by strategically translating abstract principles into practice. Both assume that actors operate within the structure of an accepted organizational discourse that includes a set of guiding principles, yet are able to creatively navigate this structure by strategically drawing upon these principles as resources they can use to solve their problems. In the case of moral imagination, organizational actors translate the guiding ethical principles that are taken for granted within the organization as right and true into creative, context-specific solutions to ethical problems through free reflection. Similarly, in the case of KCC theory organizational actors employ the knowledge spiral to continuously translate the “conceptual umbrella” provided by senior management into strategically valuable new practices.

Both MI theory and KCC theory are attuned to the management of uncertainty in ethical decision-making, providing a means by which actors can address the challenges of operating in complex and dynamic environments. As noted, moral imagination enables actors to make sense of and find a path to ethical action in an environment of competing and quickly changing discourses, while similarly, Nonaka’s knowledge spiral provides a means of rapidly synthesizing disparate bodies of knowledge into valuable new products and processes.

Integration of Nonaka’s SECI model and Werhane’s model of MI produces a depiction of the MIO as a knowledge creating company in which the knowledge spiral has been infused with principles of moral imagination. According to this normative model, these principles are at the center of organizational discourse, and as such shape and provide resources to organizational actors so that they may address the ethical issues that they enact in the course of their strategic knowledge creation and transfer activities. Organizational leaders articulate principles of moral imagination, which actors then flexibly and strategically translate through local ba into local discourses and practices. Middle managers establish and lead these ba.

The principles of moral imagination, which are instantiated in formal organizational elements such as values statements and codes of conduct as well as in informal elements such as organizational culture, could include accepted concepts associated with ethical behavior such as integrity, character, and respect for rights, as well as concepts that describe the operation of moral imagination. These could include immersion in details and personal mastery (Senge 2006), which are associated with reproductive imagination; metacognition, cognitive diversity, and collaborative inquiry (Stansbury 2009), which are associated with productive imagination; and creative and collaborative problem solving, which are associated with free reflection (Werhane, 1998). I now trace out the steps in a morally imaginative knowledge management process.

Socialization (tacit to tacit; focus on the particulars): Frontline employees and middle managers often possess rich tacit understandings and practices for addressing difficult ethical issues that arise in their operating contexts. For example, a supply chain manager operating in a complex environment may develop a set of ethical sourcing practices that take into account suppliers’ working conditions and environmental impacts in addition to factors such as cost and reliability in delivery. (This development would occur in the internalization phase, described below.) In the first stage of the morally imaginative knowledge spiral, these morally imaginative practices are transmitted locally through socialization mechanisms that involve direct interaction among individuals, such as observation and mentoring.

Externalization (tacit to explicit; from the particular to the general): In the second phase of the morally imaginative knowledge cycle, the tacit knowledge of ethical practice that is shared in the socialization stage is translated into explicit knowledge. Here actors playing similar roles in the organization (e.g., all supply chain managers) engage in dialogue and collaborative inquiry to articulate their tacit understandings into explicit knowledge of their ethical work practices. For example, supply chain managers might together codify a set of best practices for ethical raw materials sourcing. The actors involved in externalization would interact in ba such as meetings, workshops, and communities of practice (Lave and Wenger 1991; Wenger 1998).

In the combination phase of morally imaginative knowledge creation (explicit to explicit; general), various bodies of context-specific explicit knowledge of ethical practices are assembled into larger bodies of explicit knowledge. This occurs through ba such as meetings and presentations involving middle managers who translate context-specific explicit knowledge, e.g., of best practices for ethical raw material sourcing, into explicit knowledge that is expressed in terms of organizational principles of moral imagination. They would also seek to codify this knowledge in artifacts such as codes of conduct and organizational statements of values.

Crucially, in the process of synthesizing local bodies of explicit ethical knowledge into the organization’s general principles of moral imagination, the actors involved may come to identify conflicts and challenges that suggest revision of the extant principles. For example, they may come to recognize that different groups within the organization are enacting the principle of “integrity” in inconsistent ways, or that “respect for host communities” has emerged as an important issue that is not reflected in the organization’s guiding principles. Because the process of combination occurs in ba that are governed by general procedural principles of moral imagination such as collaborative inquiry, meta-cognition, and cognitive diversity, the actors involved would debate their understandings and practices, making them more likely to revise existing knowledge rather than just reproducing it. Hence morally imaginative combination is a knowledge creation process. It represents the recursive stage of the knowledge spiral, in which actors not only adhere to organizational principles but also revise them. It is worth noting that this revision of principles that takes place in the combination stage is not accounted for in, and suggests a modification to, the prevailing three-step model of moral imagination.

Internalization (explicit to tacit; from the general to the particular): In the final stage of morally imaginative knowledge creation and transfer, organizational actors establish new practices that incorporate the organization’s principles of moral imagination, as developed and modified through combination. This process of translating general principles into practice takes place in ba such as training programs, experiments, and learning by doing. Because this translation process involves the application of principles of free reflection such as creative problem-solving and collaborative inquiry, it produces new practices that address emerging ethical challenges that have been enacted. These new practices embody new tacit understandings of what works and does not work in addressing difficult ethical issues. Thus morally imaginative internalization is another knowledge creation process. Actors share the new practices they develop through socialization processes, as the cycle of morally imaginative knowledge management refreshes.

The morally imaginative knowledge spiral

The morally imaginative knowledge creation process described here would be more effective in continuously generating ethical decisions and actions if supported by appropriate organizational structure, standard operating procedures, performance measurement systems, incentives, culture, and leadership (James 2000; Paine 1994; Sims 1991). Formal ethics programs also would support the morally imaginative knowledge creation process, if re-imagined as flexible rather than coercive. For example, ethics codes would focus on outcomes rather than prescribing behaviors, and similarly, ethics training programs would serve as ba for morally imaginative socialization, externalization, and combination rather than featuring one-way communication of ethics codes and procedures. Ethics officers would take on a role of helping managers and frontline workers to translate principles of moral imagination into practice.

Conclusion

Dr. Patricia Werhane has been a giant – the giant – in the study of moral imagination in business ethics. When Werhane first introduced the concept of MI into the business ethics literature she challenged the dominant idea that ethical reasoning and decision-making involve the application of rules. Werhane was the first among business ethics scholars to recognize that the ethical issues that business managers face are too complex and uncertain to be amenable to rule application, and that ethical reasoning and decision-making could be more effective if performed as an imaginative exercise. She spelled out that this exercise works as an iteration between deep engagement in context and consideration of the implications of competing principles, including but not limited to those held by the actor. Werhane’s insights into moral imagination have resonated with scholars far beyond business.

Yet even as she was exploring the mechanics of moral imagination as an individual process in MIMDM, Werhane was also laying down the foundation for scholarship exploring MI as an organization- and systems-level concept. Werhane herself has taken the lead in building on this foundation, in the process shedding light on how organizations – and indeed, whole fields of organizations – can imaginatively devise imaginative solutions to ethically thorny situations.

While numerous scholars have followed Werhane’s lead and sought to build understanding of organizational moral imagination, much work remains to be done. Business ethics scholars collectively have only just begun to describe and prescribe the workings of the morally imaginative organization. In this chapter I have addressed this lacuna by broadly sketching out such an organization. I have done so by exploring the integration of moral imagination into the organization’s knowledge creation and transfer processes. Infusing moral imagination into these processes would ensure that imaginative solutions to ethical challenges would become the work of all organizational actors rather than that of organizational leaders alone. Further, it would ensure that moral imagination was practiced routinely as part of everyday decision-making, rather than only in response to ethical dilemmas which are experienced as separate from business decisions.

Of course, the ideas presented here are just a beginning. There exists a potentially vast area of research at the intersection of business ethics and social science which could explore how organizations can become more morally imaginative, and the ostensibly positive impacts which such organizations would have on their stakeholders, society, and nature. Existing studies located at this intersection, such as that by Arnold and Hartman (2003), Moberg and Caldwell (2007), and Werhane herself (2002, 2008) provide instructive examples. By following Werhane’s lead here, we can again honor and build upon her rich legacy.