TWO

HASKINS’S TUNNEL AND LINDENTHAL’S BRIDGE

For decades, men of ambition had stood upon Gotham’s poorly maintained wooden piers to wonder how they might breach the beautiful and strategic Hudson River. Many nineteenth-century men had conjured up grandiose plans, but the first to act was a California capitalist named Colonel DeWitt Clinton Haskins. The colonel, having built railroads out west, dug mines in Utah, and studied caisson-built bridges, proposed an ingenious and promising approach: subaqueous tunnels.

In 1873, Colonel Haskins’s vision, which called for digging two rail tunnels under the Hudson River from Jersey City to Morton Street, was sufficiently compelling to attract $10 million in capital. As soon as work began the next year, both the New York Central (determined to preserve its monopoly) and the Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad (its Hoboken terminal sure to be eclipsed) sued. They were implacably opposed to the tunnels, but after five years of litigation, Haskins prevailed. As work began, the New York Times hailed the enterprise: “Of all the great improvements projected or dreamed of in and about this City, this is unquestionably the most important.”

And so, on a cold, clear November day in 1879, Colonel Haskins’s company returned to work on its pioneering tunnels, this time digging a great, circular thirty-foot-wide working shaft near Fifteenth Street in Jersey City, one hundred feet back from the bulkhead line of the river. All through the fall, winter, and spring, gangs of men labored day and night, and had soon excavated the shaft straight down sixty feet. “It is built in the most substantial manner and is lined with a brick wall 4 feet thick,” reported one visiting journalist in the summer of 1880. “The bottom of the shaft is the level of the roadway of the tunnel, but…its bottom is now used as an immense cistern to contain the water and silt which is forced out from the head of the tunnel…The shaft contains an air-lock and a pair of engines used in forcing air and water into the tunnel.”

Colonel Haskins had devised a patented system of pumping compressed air at a pressure of twenty pounds per square inch into the advancing tunnel to keep the pressure of the river and silt from crushing his nascent enterprise during construction. “That we have gone 300 feet into the river,” said Haskins to the skeptics, “demonstrates to my own satisfaction the practicability of the work and that the air will hold the earth.” Even so, there were frequent tiny “blows” in the still-raw parts of the tunnel as the river’s extraordinary pressure penetrated the highly porous silt overhead. The “blows” made a telltale hissing sound, and the amazingly simple solution was to quickly patch the oozing spot with silt and straw before water and slimy river muck burst through, bringing deluge and disaster.

The New York Times reporter who came in mid-July 1880 to view the tunnel digging was given a suit of blue overalls, rubber boots, and a floppy hat. The young journalist then warily descended the ladder halfway down the brick-lined shaft where a “slippery blue black mud covered everything.” There loomed the air lock, an ominous boilerlike iron object, fifteen feet long and six feet tall, that was the sole entry to the tunnel works. With trepidation, the journalist and his guide stepped into the dungeonlike space of the air lock (lit only by a sputtering candle), and the heavy door with its thick bull’s-eye window clanged shut.

For fifteen minutes, the men sat in the gloom as the air pressure gradually increased, a process the reporter likened to “torture.” Then the air lock door on the tunnel side (also with a thick round window) slowly swung open. The tunnel was a clammy, stygian space, illuminated by calcium lamps, smelling of human sweat and rank mud. In almost nine months, Haskins’s tunnel teams had burrowed deep under the river and had already advanced the north tunnel three hundred feet through the silt toward Manhattan. The sweating reporter and his guide advanced down a steep slope and slithered through a narrow opening into the north tunnel, where the air was cooler. Almost the entire length of the excavated twenty-foot-high tunnel was deliberately refilled halfway with dirt, intended “to furnish a brace to the brick-work, and allow the cement to thoroughly harden, until the tunnel is finished.”

Far ahead, miners stood atop an earthen staircase picking and shoveling to create “a thin semi-circular opening at the top of the tunnel, only excavating enough at a time to admit of placing the top [round iron boiler] plates in position,” that were then welded together. As the top half of the tunnel advanced, other miners steadily excavated the lower half. As soon as the welders attached the top and bottom iron cylinder, the brick masons lined the iron cylinders with cement and a two-foot-thick layer of bricks. Even as he was feeling miserable, the reporter admired this daring subaqueous enterprise, finding that “Everything about the tunnel appeared solid and substantial.” He retraced his steps, endured the air lock, and returned gratefully to the fresh summer air, the sunshine, and river breezes. He sat for a while. The last visitor, in his haste to escape, had overexerted himself and fainted.

An 1880 illustration of Haskins’s tunnel project under the Hudson River.

Three days later, in the dark predawn hour of 4:30 a.m., fourteen tunnel workers, having completed their lunch break up in the night air, acclimated in the air lock and stepped into the outer chamber of the tunnel where twelve men were waiting to head up for lunch. Suddenly, they heard the telltale hissing of a breach in the chamber. The blowout in the still-unbricked vault was too big and fast to be plugged, and with a sharp crack, the heavy joists snapped like bamboo. Timbers, iron, and mud began engulfing the tunnel. Eight men frantically clambered back into the air lock, then watched in horror when their fellow laborers were overwhelmed by oozing mud and debris, pinning one man half in the open air lock door.

“‘My God! The water is gaining on us,” said one, ‘what shall we do?’

“‘Keep cool, men; keep cool,’ answered a voice from the river side of the tunnel.” It was their supervisor. As the water rose relentlessly about him and the others, he calmly instructed the men in the lock to pull off their clothes and stuff them around the jammed-open door to keep out the water. The water slowed but still rose steadily in the tunnel and the air lock. Now their boss’s voice, sounding far away, commanded, “Break open the bull’s eye.”

The men, naked in the air lock, the cold water rising toward their chests, hesitated, knowing if they broke the window on the shaft side, the others would almost certainly not escape.

Again, their boss ordered sternly, “Knock out the bull’s eye; knock it out I say,” and then faltered, “and do what you can for the rest of us.”

At that they smashed away at the thick outer bull’s-eye window, the cold water inching higher, lapping at their arm pits, then their necks. Then the air lock door burst open, pried open by rescuers. The eight men burst out into the shaft with the rush of water and waded helter-skelter toward the ladder. Up they stumbled to the surface, river water swirling just below and rising rapidly.

Once out and safe on solid ground, they stood naked and mud-smeared, heaving as rain drummed down all around in the dark. Beside them the whole shaft filled with roiled river water, becoming a muddy pool. Below its surface, twenty of their fellow workers were entombed. As the wet dawn lightened the sky, a thousand relatives and friends, eerily quiet but for occasional weeping, ignored the lashing rainstorm to press in around this flooded grave. As the New York Herald observed, “Engineering skill had set at defiance the laws of nature, and nature had avenged herself.”

Eventually, Haskins, undaunted, pumped out the tunnel, recovered the corpses, and recommenced work. After all, he would explain, “This tunnel scheme is a bona fide operation. I put a fortune in it myself, and seven years of labor…If the scheme is successful it will pay me; if it fails, I shall lose.”

Should it succeed, his tunnel would be the rail link into Gotham at a time when the Commercial and Financial Chronicle wrote, “The fact is that the railroad has revolutionized everything.” All through the final decades of the nineteenth century, fast-expanding railroads were remaking the United States, whether Americans liked it or not, determining prosperity or obliteration with their routes and their rates. The raw power of the railroads was a marvel and a terror. “Many of these roads had a greater income than the States they served,” wrote railroad historian John Moody; “their payrolls were much larger; their head officials received higher salaries than governors and presidents. The extent to which these roads controlled legislatures and, as it seemed at times, even the courts themselves, alarmed the people.”

Starting on November 18, 1883 (“the day of two noons”), the telling of time itself, once set by the sun, had to be standardized to fit the new mechanical world of science and railroads. Within six months, seventy-eight of America’s hundred biggest cities set their clocks and watches to Railway Standard Time. As an Indianapolis paper joked, “The sun is no longer to boss the job. People…must eat, sleep, and work…by railroad time…People will have to marry by railroad time.”

Colonel Haskins, desperate to finish his trolley tunnels, pressed on. By late 1887, far behind schedule and digging only sporadically, he had completed 2,025 feet of the 6,000 feet under the river. He was running out of money and was unable to convince investors to ante up another penny. Two years later, the British-backed S. Pearson & Son excavated another 2,000 feet before another bad blowout scared off financing and forced them to abandon the tunnel in August 1891. The obstinate Hudson River waters flowed serenely on, and the railroads—save the Vanderbilts’ New York Central—still came to an impatient halt at the many terminals on the Jersey riverfront.

Even as Colonel Haskins tunneled far below the Hudson River in fits and starts, the equally ambitious bridge engineer Gustav Lindenthal, a tall, elegant Austro-Hungarian immigrant with a Van Dyck beard, stood on Gotham’s wharves. The year before, the Roeblings’ Brooklyn Bridge had opened to universal acclaim. A triumph of engineering, the bridge was also a work of art, a noble structure whose wondrous web of cables, latticed girders, and masonry towers glistened poetically in the city’s sun and shadow. Now, the erudite and charming Lindenthal, educated in Europe as a civil engineer and the preeminent bridge engineer in river-girt Pittsburgh, planned to make an even greater mark on New York. Hoping to build a great bridge to span the mile-wide Hudson, one almost twice the length of the Brooklyn Bridge with its span of 3,455 feet, he organized the North River Bridge Company in 1884, only to be stymied by the financial hard times of the late 1880s.

By 1890, the economy finally recovered, Lindenthal and his backers spent January and February haunting the underheated halls of Congress, emerging on April 11, 1890, with a valuable federal charter. The North River Bridge, asserted one witness, “is in national importance on a level with the Union and Central Pacific Railways or the Nicaragua Ship Canal.” Prize in hand, Lindenthal came knocking on the Pennsylvania Railroad’s monied doors.

Just as the PRR prepared to move, the Panic of 1893 struck. The booming economy spiraled into a slow-motion free fall. In these hardest of times, a third of the nation’s railroads went belly-up. Wall Street titan J. P. Morgan, his girth and power ever expanding, scooped up so many of them, he gained control of a sixth of the nation’s rails. For Lindenthal, however, one bright spot came in 1894, when the U.S. Supreme Court upheld his bridge charter.

Among all the visionary engineers and hard strivers dreaming of monumental New York bridges and tunnels, it might seem odd that the man who had dreamed longest about this great and vexing dilemma—how to connect the wealthy and influential island of Manhattan to the mainland and the rest of America—should be a Philadelphian. Yet it was Alexander J. Cassatt who had first extended the Pennsylvania Railroad lines up to Jersey City in 1871 and developed the whole system of New York ferries. Ten years later, even as New York was surpassing Philadelphia as the nation’s leading port, Cassatt not only fended off a rival road’s move to control the PRR’s access to Jersey City but seized ownership of its rails.

The story of how Cassatt pulled off this coup—guaranteeing PRR access to New York City—came to be famous. In 1881, Cassatt was forty-two and the road’s first vice president when John W. Garrett of the Baltimore & Ohio sashayed in to crow over securing complete control of the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad, a road whose tracks were used by the PRR to reach New York. The porcine Garrett, whose large sideburns compensated for his balding pate, assured the PRR’s cautious president, George B. Roberts, “We are not disposed to disturb your relations with the property and you need not give yourself any uneasiness on that score.”

“‘Well,” replied Mr. Roberts, in his dry manner, “I did not know that you had progressed so far in your negotiations.”

As soon as Garrett left, Roberts rushed out to tell Cassatt the bad news: “Garrett says they’ve got the PW&B.”

“Oh no they haven’t,” countered Cassatt, who had hoped for the presidency and chafed under Roberts’s too-prudent style. Cassatt had no intention of being dependent on the kindness of the B&O to get his company’s trains to New Jersey. Cassatt raced to New York City, secured a big block of stock, and offered a better cash-on-the-line deal for the small road. That night, the PRR’s board of directors authorized the purchase and the $14,999,999 check written on March 8, 1881, was then the largest single such deal in American business. The framed check hung for years in the offices in Philadelphia. It was this bold vision, decisiveness, and ability to execute the details that had always distinguished the apparently reserved Cassatt. And thus, the Pennsylvania gained “perpetual control of the traffic of the South and Southwest and brought into the family another rich feeder for its New York lines.”

Unlike up-from-the-bottom Gilded Age titans like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller, the tall, reserved Cassatt was a son of privilege. His father had made a fortune in banking and real estate first in Pittsburgh, then in Philadelphia before he retired to Europe for five years in the early 1850s with his wife and five children. When the family returned to the United States, Aleck (as his family called him), by now fluent in French and German, remained to complete his studies at a gymnasium in Darmstadt, Germany. He returned home to earn a B.S. degree in civil engineering in 1859 from the rigorous Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York. His sister, Mary Cassatt, would eventually return to Paris and spend her life there as an expatriate artist.

After completing his degree at RPI, Cassatt worked briefly for a railroad in Georgia, where he toyed with the idea of starting a vineyard. With the outbreak of the Civil War, he headed north, not to enlist, but to join the Pennsylvania as a lowly rodman and surveyor’s assistant for a dollar a day. The railroad played a pivotal role in the Union victory and was beginning its great expansion from Pittsburgh, where the mines and belching black mills and furnaces would soon be churning out stupendous tonnages of coal, iron, and steel. During the war, however, Cassatt was still an underling. For two years, “it was hard work tramping over hard places, struggles with underbrush, swamps, brambles, with heat, with cold, and with the hardships of camp life in desolate places.” Young Cassatt discovered he had an enormous capacity for work, detail, and organization as well as a talent for getting along with men of all stations.

One day in April 1866, when Cassatt, then twenty-six, had been promoted to superintendent of motive power and machinery of a PRR subsidiary, the Philadelphia & Erie, Colonel Thomas A. Scott, Cassatt’s dashing superior, paid him a visit. When he posed to Cassatt various bookkeeping questions, “Cassatt reeled off the figures,” relates Cassatt’s biographer. “Scott was amazed at his memory. ‘How do you know that?’ Scott asked the young manager. ‘Oh,’ said Cassatt in an off-hand way, ‘I think it’s a pretty good scheme to go through the books every few days, so that if anything happened to the bookkeeping department I might not be left in the lurch.’” And so young Cassatt’s prodigious grasp of detail and his astonishing memory were revealed.

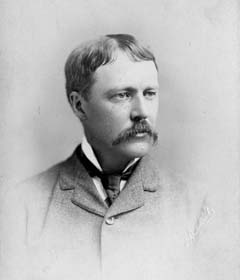

Alexander J. Cassatt as a young man.

Another longtime manager, who had looked askance at Cassatt’s elegant frock coat and silk top hat, was similarly amazed to find that this quiet new officer “seemed to grasp the whole situation in a few hours, and in a day or two after he had gone over the road, he knew more about that than we did who had been there for a year.” Equally impressive, Cassatt showed “a natural talent for machinery and when riding over the road he would almost invariably be found handling the [locomotive], while the engineer rested. He was a good ‘runner’ and made good time.”

The ambitious, charismatic Tom Scott was then the railroad’s vice president and young Cassatt his foremost protégé. During his meteoric ascent at the Pennsylvania Railroad, Cassatt helped construct its much-envied network in “that important territory between Pittsburgh, the Great Lakes and the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, while at the same time other leases and acquisitions had extended it into the Monongahela and Allegheny valleys and other coal fields of Pennsylvania.” All the while Cassatt was seeking and delivering better, faster, safer, and more standardized rails, locomotives, and cars. A bold and original thinker, Cassatt persuaded his deeply skeptical superiors to adopt young George Westinghouse’s air brake, a new and revolutionary invention that allowed the engineer to control the brakes on trains, rather than relying on numerous brakemen leaping from car to car, manually turning uncertain brake wheels. The air brake transformed the industry, allowing ever-longer, heavier trains to operate far more swiftly and safely, while eventually rendering the one-legged brakeman obsolete.

Promoted to a position in the company’s manufacturing heart at Altoona, Cassatt now focused on standardizing the PRR’s locomotives that were built and tested at the railroad’s great shops and roundhouses. While there, Cassatt wooed Lois Buchanan, an Episcopal minister’s daughter and the proud niece of former President James Buchanan. Showing his light-hearted side, Cassatt wrote his sweetheart, “You sing divinely, I adore music, you are fond of fried tomatoes, I dote on them! So you see we agree on all important points.” Utterly smitten, Cassatt wrote Lois, “I see you now as you sat at the table yesterday evening—your face and hair illuminated into the most beautiful color—the roses in the bouquet could not vie with the beauty of your complexion, and your eyes—the brightest in the world—never was there a more engaging picture.”

Cassatt approached his coming wedding and new home with characteristic enthusiasm and care. He made many trips to Philadelphia with Lois to consider home furnishings and wrote her, “I had to send back the paper we selected on Saturday. I found that the blue rubbed off so easily that your dresses would have been spoiled.” He worried about where to place his parents’ wedding present, an elaborate antique French clock once owned by Marie-Antoinette, and where they might best hang the beautiful mirror from President Buchanan’s estate.

By 1873, Tom Scott was poised to become president of the Pennsylvania, and Cassatt had risen to general manager of the lines east of Pittsburgh and Erie, the most important part of the sprawling system. In that post, among many other things, he imbued “the road’s employees with the discipline and the politeness that have worked to make the road famous the world over. He equipped the track with the block signal system, and introduced the track [water] tank.” As the PRR took to boasting in its advertising, “Speed, Comfort, and Safety Guaranteed by Steel Rails, Iron Bridges, Stone Ballast, Double Track, Westinghouse Air Brakes, and THE MOST IMPROVED EQUIPMENT.”

Thomas A. Scott, president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, 1874–1880.

The very size and complexity of the railroad corporations was completely new, hard to grasp. A mere twenty-five years earlier, in the 1850s, one of the nation’s greatest industrial enterprises was the Pepperell Manufacturing Company in Biddeford, Maine. These giant textile mills cost about $300,000 a year to run and employed eight hundred hands. By 1859, those mills were already being dwarfed by nascent railroads, like the PRR and the Erie, with their operating budgets of millions per year and tens of thousands of employees. And while mill managers supervised their eight hundred hands all in one place, “railroad managers had to make decisions daily controlling the activities of men whom they rarely talked to or even saw.”

Railroads, which reduced the cost of transportation to a fraction of what had been offered by horses, rivers, and canals, created a truly national and international marketplace, new industries, and a new industrialized world. “In all of the human past,” writes historian Martin Albro, “no event has so swiftly and profoundly changed the basic order of things as had the coming of the railroad.” In twenty-five years American railroads forced a bigger managerial revolution, points out historian Harold C. Livesay, “than had occurred in the previous five centuries. Before the railroad…[it was] experience, instinct and information…No such casual arrangement could obtain on the railroads…unreliable, incompetent, or insubordinate workers…could cause wrecks, damage property, and kill people.” In fact, the carnage the railroads wreacked was unprecedented. In 1897, almost 6,500 Americans died in train accidents, most from being hit while on the tracks, while another 36,731 were injured. Almost 1,700 railroad workers were killed that year, while 27,700 were injured.

By 1877, when the PRR controlled five thousand miles of track, writes historian Robert V. Bruce, “No private enterprise in the nation’s experience had ever equaled the Pennsylvania’s wealth and power…From the Hudson to the Mississippi, from the Great Lakes to the Ohio and the Potomac, from the prairies of Illinois to the marshes of the Jersey coast, the rails of the Pennsylvania system stretched shining and unbroken.” In 1877, this great road was capitalized at $400 million, earned profits of $25 million, and employed an army of twenty thousand men. Lord Bryce had watched in wonder at the American railroad: “When the master of one of the great Western lines travels towards the Pacific in his palace car, his journey is like a royal progress. Governors of States and Territories bow before him; legislatures receive him in solemn session; cities seek to propitiate him.”

Nevertheless, PRR president Tom Scott, tall, elegant, with a distinctive white mane of hair and mutton-chop sideburns, was, by this point, seeking fresh revenues. He decided that the PRR, which carried two-thirds of the refined output flowing from John D. Rockefeller’s up-and-coming Standard Oil Company, would itself take up refining the black gold. Scott fatally underestimated Rockefeller, who responded with fury, writing, “Why, it is nothing less than piracy!” Rockefeller retaliated with a boycott that cost the hard-pressed Pennsylvania $1 million. Colonel Scott further cut his workers’ wages (as did other struggling roads in these hard times) in the middle of a sweltering July and doubled the length of each train. The PRR’s firemen and brakemen in Pittsburgh struck.

Cassatt rushed to the scene, the sole PRR officer intrepid enough to enter the tense city. “I thought that my duty ought to be there, and I got on a train and went.” As Cassatt rolled into Union Depot that muggy Friday afternoon of July 20, nine hundred of his road’s loaded freight cars were blocked from leaving Pittsburgh by a fast-swelling crowd of PRR strikers, young rowdies, and the merely curious. When the sheriff failed to disperse the strikers, Cassatt, highly visible in a tall white hat and light suit, proposed bringing in militia from Philadelphia.

The next day, six hundred uniformed soldiers arrived. Cassatt, who wanted his freight trains freed, would later relate, “I went down with the troops as far as the western round-house, and went in there with the plan of starting the trains at once, as soon as the tracks were cleared…the foreman of the machine shop came to me, and said a riot was going on outside, and I got on the roof.” There, only a hundred and fifty yards away in the oppressive afternoon heat, the belligerent mob was taunting the militia, tossing stones, pieces of iron, and other debris, jeering curses.

“They all seemed to be shouting and hallooing,” said Cassatt. “There was quite a shower of stones.” Cassatt suddenly heard a sickening sound: shots. The shots, he said, were “fired by the crowd, and then I saw the troops fire in return…It lasted a minute or two minutes, and I could see the officers trying to stop the firing, after it commenced.” Others said the militia fired first. However the shooting began, when it was over, Cassatt could see splayed bloody bodies all about. Twenty were dead, twenty-nine wounded. The militia in their stained light blue uniforms retreated harum-scarum to the huge roundhouse.

Tom Scott’s ill-starred battle with Standard Oil, and Cassatt’s ill-advised call for the militia had ignited Pittsburgh’s Great Railroad Riot. All that long night Cassatt and other leading citizens watched a Pittsburgh mob, now five thousand strong and many armed, commandeer PRR coal cars, drench the anthracite with oil, toss in burning torches, and shove these rolling bonfires down the tracks toward the Pennsylvania’s Union Depot. Young men giddy on looted liquor donned hoop skirts and took up the can-can. A great conflagration spread across the sprawling PRR yards, engulfing the fine terminal and its attached hotel, devouring both in towering flames. The Philadelphia militia soon faced a Hobson’s choice: emerge from the roundhouse whence they had retreated or be roasted. By the time the militia escaped, twenty more Pittsburghers were dead, many wounded, and several soldiers killed.

When the sun rose the next morning through the fire’s filthy haze, the PRR depot and yard had been reduced to a scorched tableau of smoldering ruins and train skeletons. All told, $5 million in prime PRR property had been incinerated—39 buildings, 104 prized locomotives, 46 passenger cars, and about 1,000 looted freight cars of every kind.

The Great Strike of 1877 spread like wildfire to a hundred towns coast to coast, unleashing anarchic violence as workers shut down the nation’s most vital rails, coal fields, and factories. The New York World headline blared, “RIOT OR REVOLUTION?” Mobs clashed with militias and police, leaving one hundred more dead. The Pittsburgh Leader declared, “This may be the beginning of a great civil war in this country, between labor and capital.” Only when the railroads and coal mines grudgingly made concessions that August did uneasy civil calm return.

When Cassatt wearily returned home to Haverford and his worried wife and four children, he was covered from head to toe with prickly heat. The contrast between the cool green fields and trees of his Main Line estate, Cheswold, and the scorched destruction back in Pittsburgh must have been grievous. These were nights that he would never forget and would rarely speak of. He has seen firsthand the violence, the fury sparked when powerful corporations pushed their men too far, and when the workers of this new industrialism felt too aggrieved. Nor was that the end of it.

The torched Pittsburgh PRR yards after the 1877 Railroad Riot.

So great were the PRR’s losses that Colonel Scott had capitulated to Standard Oil by mid-October. Not only did Scott give Standard Oil secret rebates on every barrel of oil the company shipped, he also gave Rockefeller secret rebates—drawbacks—on every barrel Standard Oil’s competitors shipped. Scott and the PRR bestowed upon Standard Oil the covert means of establishing a ruthless monopoly. “Through this secret arrangement,” wrote Pearson’s Magazine, Rockefeller “laid the foundation of the greatest fortune in the world, and crushed his competitors in the oil business with no more pity than a Sioux warrior would show to his enemy.”

As much as Cassatt loved railroads, he saw this new and corrupt system of secret rebates and drawbacks as poisonously unfair. Why should Standard Oil pay less per barrel than any other oil producer to ship its product? Much less get a drawback for their rival’s barrels? Nor could Cassatt stand the rancorous and self-serving robber baron tactics that undermined the proper running of many railroads, enterprises so critical to the nation’s well-being. Why were men like Jay Gould and his ilk allowed to fleece unsuspecting stockholders by manipulating roads?

Even the PRR’s own president, the swashbuckling Colonel Scott, had played fast and loose with certain slippery, self-serving deals. By mid-1880, hopelessly tarnished by his reckless pursuit of a transcontinental railroad empire and the disastrous Pittsburgh riots, Scott resigned. His reputation, fortune, and health were in precipitous decline and he died within the year. The conservative PRR board of directors, feeling burned itself, elevated to president the cautious and prudent George B. Roberts. Roberts, an ardent Episcopalian, with such good works under his belt as the creation of both the Young Men’s Christian Association and the Free Library, built the Church of St. Asaph in Bala near his mansion on the Main Line. Cassatt, only forty, but disappointed at being passed over and uneasy with a world where powerful corporations bullied and cheated, began to contemplate his departure from the Pennsylvania Railroad.