EIGHT

“CROOKED AND GREEDY”

Just as policeman Clubber Williams thought it wise to resign after his grilling by Lexow, Tammany Democratic chieftain Richard Croker, the epitome of disciplined corruption, thought it best to decamp to England for self-imposed exile lest he be called to testify. “Like many other millionaires, Croker had come up the hard way,” writes historian Lloyd Morris. “Stern-visaged, cold-eyed, with the heavy body of a bruiser, he was a study in iron grey—hair, beard, handsome suit, and overcoat were all of the same dark hue. Croker, the child of poor Irish immigrants, had landed in New York in 1846, at the age of three. He had little schooling, a rough youth as a member of the Fourth Avenue Tunnel Gang, got on the city payroll in his early twenties, served as alderman in the regime of Boss Tweed, was tried for murder after an Election Day battle and set free because the jury disagreed. But all this was now far in the past.” Still that past cast a powerful shadow and few dared to cross Boss Croker.

In England, the thuggish Croker moulted into an approximation of British gentry, sporting the proper (if unconvincing) plumage of formal suit, gleaming top hat, and expensive cane. He acquired the requisite London town house, stables near Newmarket racecourse, and a moated country estate in Wantage, Berkshire. There Croker indulged his every whim and his passion for expensive horses, cutting an unlikely figure on the English turf and racing circuit with his trademark black cigar clenched in his mouth.

New York Democratic boss William Croker at the race track.

The less polite New York press quickly dubbed Croker the “Baron of Wantage,” and gleefully reported the Tammany boss’s new hobby of raising world champion bulldogs, with one famous puppy rumored to cost ten thousand dollars. But, wrote one biographer, “Croker’s greatest fun was feeding the pigs. These he had named after New York politicians whom he knew to be crooked and greedy.” Thanks to the miracle of the telegraph, Croker could play the English squire even as he ran the Tammany Wigwam with an autocratic iron fist. He deigned to return to Manhattan (he had another horse farm in New Jersey) in formal sartorial glory only to manage crises and direct strategic elections.

With his simian air of ferocious, sullen reserve, he exuded an intensely intimidating power dedicated to horses, graft, and politics. For decades, Tammany Hall had ruled through a very simple formula, explained by Croker in a rare interview: “Think of the hundreds of foreigners dumped into our city. They are too old to go to school. There is not a mugwump [reformer] who would shake hands with them…Tammany looks after them for the sake of their vote, grafts them upon the Republic, makes them citizens in short; and although you may not like our motives or our methods, what other agency is there…If we go down into the gutter, it is because there are men in the gutter.”

It was really quite elementary, wrote muckraker Lincoln Steffens: Tammany owned the “plain people” because in the absence of government services, Tammany provided a helping hand. “They speak pleasant words, smile friendly smiles, notice the baby, give picnics up the River or the Sound, or a slap on the back; find jobs, most of them at city expense, but they also have news-stands, peddling privileges, railroad and other business places to dispense.” And with those votes, Tammany ruled city government and its tens of thousands of jobs and the vast ocean of boodle harvested from controlling the docks, the police, the health department, and the courts. It was a reliably rich take. The Pennsylvania Railroad could make it even richer.

Along with Croker the other virtual political dictator of New York was U.S. Senator Thomas Collier Platt, fifteen-year absolute monarch of the state Republican machine and legislature. Platt had the look of a pallid haberdasher’s clerk and cared only for the minutiae and power of politics. Unlike the men of Tammany, whose “offices” were generally located in neighborhood saloons (though few top leaders ever touched a drop of liquor), the “Easy Boss” (as he was known) held court each Sunday in the “Amen Corner” of the plush Fifth Avenue Hotel. There he had long lived with his wife (though now he was a widower), and endlessly parsed elections and appointments and made deals with loyal leaders who came on pilgrimage from all over the Empire State. In his first stint in the U.S. Senate, Platt was derided by journalist William Allen White as a political “dwarf.” When Platt entered the U.S. Senate for the second time in 1897, White described him as cutting “a small figure. He was a negligible man…He took no active interest in the large trend of national events…he was miserable until the tedious business of a session was done. Then back at his express office, or sitting at his desk in the Fifth Avenue, he could gloat over his power.”

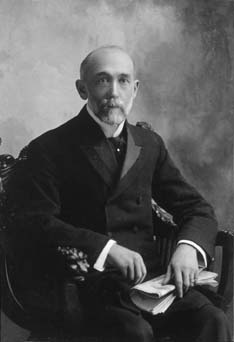

New York Republican boss Thomas Platt.

Unlike Richard Croker and others of the Gilded Age bossocracy, Senator Platt did not steal, nor did he, wrote even his nemesis Theodore Roosevelt, “use his political position to advance his private fortunes…He lived in hotels and had few extravagant tastes.” In contrast to Tammany and its legions of poor, immigrant voters, Platt’s supreme power came from catering to the great trusts and corporations doing business in Albany. Their grateful largesse flowed into Platt’s formidable Republican campaign chest. Platt distributed these dollars with strategic care to his chosen candidates and district leaders during elections. Total fealty ensued. Platt’s word had long been the law up in Albany at the state legislature.

William Baldwin and Alexander Cassatt would soon have to navigate the political waters where these two very different men had long reigned supreme. A construction project of the magnitude they planned—sixteen miles of tunnels, a monumental terminal, and a huge rail yard—could not move forward without all manner of franchises and legislation at every level of government.

Theodore Roosevelt had, of course, been a great and unhappy exception to Platt’s usual ways; Platt had backed him for governor only under severe duress. As hero of San Juan Hill and famous for his probity and honesty, Teddy seemed the only Republican candidate likely to win the governorship in the wake of a particularly rank embezzling scandal. Due to the assassination of President McKinley, the obstreperous and unreliable Teddy had triumphed, joyfully ascending to the Bully Pulpit of the presidency. Alas, Senator Platt had also miscalculated when he rammed through legislation creating Greater New York City, in the hopeful (but deluded) belief that the new outer boroughs would furnish more Republicans than Democrats, and thus a juicy plum for his party. Instead, it had created more boodle for Croker and the Democrats, who in 1897 had installed Robert Van Wyck as first mayor of consolidated Greater New York.

In truth, Croker and Platt often coexisted peacefully, divvying up Gotham’s plentiful spoils. But in 1899, the Easy Boss could not resist twisting the Tammany Tiger’s tail by unleashing the second state investigation (known as the Mazet Committee) into Gotham’s lubricious graft and corruption. This time the brooding Richard Croker himself was forced to take the stand and testily admit to pocketing Tammany rake-offs from judges (at $10,000 per) and others. The prosecutor asked, “Then you are working for your pocket, are you not?” Croker snapped back with words that acquired instant infamy and immortality, “All the time; the same as you.” The drawn-out hearings, filling five fat volumes worth of testimony, revealed the long-entrenched system of vice and police protection to be more flagrant than ever, a fact of little moment to the great mass of Tammany voters. What Mazet confirmed about the ice business was altogether another matter.

In May 1900, as the weather warmed, New Yorkers buying ice—an absolute necessity for keeping milk and meat from spoiling—had been stunned to hear the price had inexplicably doubled from thirty cents a hundred pounds to sixty cents. In the tenement districts, the poor wanting to buy the cheap five-cent pieces were turned away. Ice was for sale only in one hundred-pound blocks. Young William Randolph Hearst’s crusading Journal American unleashed its best lawyers and reporters, demanding in giant headlines “PUT AN END TO THE CRIMINAL EXTORTION OF THE ICE TRUST.” Day after day, Hearst pounded away, splashing heartrending cartoons across the American’s front page to drive home the infamy of it all. In “The Ice Trust and the Poor” a weeping young waif clad in rags stood by her feverish, bedridden mother, murmuring, “Can’t get any ice, mamma; the trust man says they won’t sell any more small pieces to poor people.”

Hearst eventually dug up the scandalous and Augean truth: the Ice Trust was the creation of Tammany officials, including Gotham’s own mayor, Robert Van Wyck. The scheme was simple: Only their company’s ice barges could unload on city-owned piers. Over in Wantage, Richard Croker was sufficiently displeased to prepare to return to Gotham. Grafting off the poor (and getting caught red-handed) was bad Tammany politics.

The Mazet hearings roiled up all kinds of vile murk. Hundreds of witnesses detailed a debauched underworld—brothels, “panel” houses where thieves stole wallets from unsuspecting men engaged in sex, “cinema nights” where voyeurs paid to secretly peep into rooms where whores were plying their trade, new legions of prostitutes operating out of tenement houses full of young children, and, most horrifying, the rise of white slavery. The respectable newspapers found it hard to cover the story. Tammany police had become so greedy that denizens of the underworld were pleased to expose them. One witness, proprietor of the White Elephant in the Tenderloin, complained about the outsized bribes police now demanded. He also testified, “There are more gambling houses and more disorderly [whore]houses open, running business openly, a great many more.” Police chief Richard Devery, a bloated buffoon grown immensely rich on graft, denied all, saying with his trademark smirk, “Touchin’ on the question of gambling, I’ll say that when the department gets evidence it will act…We will act any time on the complaint of reputable citizens.”

Certain reform-minded middle-class citizens, infuriated by the Mazet dirt, had decided to call the insufferable Chief Devery’s bluff. He wanted evidence of crime and corruption? They would bombard Tammany with all the evidence Big Bill Devery could ask for. Their leader was the charismatic William Baldwin, president of the Long Island Rail Road. At rallies and meetings, the handsome young Baldwin exhorted his listeners to action: “Last fall there arose in this city a cry, an agonized cry, from fathers, mothers, and daughters, that vice was rampant in the city. It was a cry for help that scarcely anybody could endure. It was out of this…that the Committee of Fifteen was born.” The committee raised money, hired private detectives, and sent them forth to methodically gather evidence and force prosecutions. There were some who saw in the activist young Baldwin a potential future mayor. After all, he was young, smart, good-looking, a hard worker, a respected businessman, and a very winning personality. And he got results. The reformers, true to their word, month after month stacked up ample proof of gambling, graft, and prostitution.

All the hue and cry led one Tammany district leader, the redoubtable George Washington Plunkitt, to daintily explicate about “honest graft and dishonest graft.” The latter, which he did not care for, relied on “blackmailin’ gamblers, saloonkeepers, disorderly people, etc…. [Then]there’s an honest graft…say, they’re going to lay a new park at a certain place. I see my opportunity and I take it…I buy up all the land I can…Ain’t it perfectly honest to charge a good price and make a profit…Well, that’s honest graft.” These were exactly the sort of sentiments that made the Pennsylvania Railroad chary as it contemplated embarking on the nation’s largest civil engineering project in the heart of Gotham.

Meanwhile, letters and phone calls poured in to Baldwin’s reform group from New Yorkers angry about local riffraff and criminals. Between those and the Fifteen’s own private inquiries, the president of the LIRR had come to obtain his firsthand education about many of the very blocks in the Tenderloin that the PRR now needed to buy. On West Thirty-first Street, warned one caller, right behind the Nineteenth Precinct police station house, “four or five houses are regular houses of ill-fame. Soliciting is going on from the windows.” Another wrote furiously about a saloon on the ground floor of his Seventh Avenue apartment building, “a dive of the worst character…The most vile and filthiest streetwalkers in the neighborhood, white and colored, are harbored in this place all day from sunrise till long after midnight, much to the disgust and annoyance of the tenants, all respectable people.”

While many Gothamites felt little ire over gambling, Sunday drinking, or hardened streetwalkers, almost all recoiled at white slavery. The new Republican justice William Travers Jerome (a last-minute gubernatorial appointment before Teddy headed to D.C.) barnstormed the city bluntly describing how squads of smooth-talking Lotharios called “cadets” (protected by Tammany) now worked the immigrant tenement districts, luring naive young women into “romances.” Promised respectable matrimony, these innocents instead found themselves imprisoned in brothels and “ruined.” “The girl in there [the whorehouse] has no means by which she can escape,” explained Jerome, a most unlikely looking firebrand with his rimless glasses and bow ties. “Her clothes have been taken from her: she has perhaps a wrapper, a pair of stockings, and slippers…Literally, screams issuing from the upper windows of such a house, and heard by men in the street, are by policemen in the street not heard or investigated. They do not dare hear; they do not dare investigate; the keeper of the house pays protection. You hear talk about the horrors of white slavery…like hearing evil fairy tales…of far-off lands.” But it was a chilling and growing reality in the Manhattan of 1901.

As other reform groups mobilized and pressure built, Richard Croker returned home, gathered his leaders, and tersely instructed them to rein in the worst of their excesses. When one Tammany brave objected, the grizzled Croker bounded up in fury, hissing, “If the people find anything is wrong, you can be sure that the people can put a stop to it, and will!” When Croker sailed back to England, however, his minions were in sullen revolt, determined to keep raking in the lucre of vice, said to be $3 million a year for the police department alone.

Tammany predictably began subterranean whisper campaigns, warning Baldwin that if he persisted in his investigations he “would find his business responsibilities interfered with, that means would be devised for hampering the operations of the railroad corporation of which he was head.” As the rumors and threats swirled about, Baldwin declared, “I have taken up this work for the city and I propose to go on with it. If there is any dread lest my responsibilities in the management of the railroad may be interfered with, my resignation as President is ready. This work of the Fifteen I have promised the community to do, and I shall do it to the best of my ability.”

It was not hard to imagine the PRR’s directors rather taken aback to find the president of one of their new subsidiaries engaged in such lurid rabble-rousing. Negro uplift was all very well, but rousting out prostitutes? Even as Alexander Cassatt was inspecting the Quai d’Orsay Station and then seeking out Jacobs in London in August 1901, Committee of Fifteen investigators pressed on, engaged in their own unusual inspections, again and again documenting that prostitution continued to be open and rampant. During a typical encounter in the Tenderloin on the warm midnight of August 30, a dark-haired French woman at 128 West Thirty-first Street solicited the two detectives engaged in this odd form of civic betterment.

Once inside with the men, she disrobed, reported John Earl, “She got on the bed, exposed her parts to me and wanted me to have sexual intercourse with her which I declined to do.” Instead, he dutifully filed his report, one of hundreds showing what police routinely ignored. Little did William Baldwin dream the previous summer that his antivice crusading and the PRR’s most fundamental interests were soon to intersect in this seamy neighborhood. And yet within months this benighted piece of real estate had come to be absolutely essential to the PRR’s decades-old dream of conquering Gotham.