TWELVE

“UGLY RUMORS OF BOODLE”

Young William Randolph Hearst’s populist, powerful, and widely read Journal American immediately attacked Mayor Seth Low for signing the tunnel bill, trumpeting “A Colossal Robbery of the People of New York in Progress.” This was a disturbing development for the Pennsylvania Railroad, for Hearst was a dangerous enemy, as Tammany had discovered during the Ice Trust scandal. His editorial particularly objected to the perpetual franchise, asserting, “It is infamous that the rights of the people in these franchises, worth hundreds of millions to the Pennsylvania Company, should be given away forever…IT IS A JOB. A GIGANTIC JOB.”

Oddly, Hearst, himself a rampaging reformer, had taken a vociferous dislike to the new mayor. In early March, William Baldwin had made sure the PRR’s Philadelphia office saw a Hearst editorial attacking Low as a “snob,” leading “an administration of men who look upon the ordinary voter exactly as they look upon one of their servants downstairs in the kitchen.” Moreover, the Hearst paper portrayed Low as a yacht-owning elitist in cahoots with the Pennsylvania Railroad, evidenced by his appointment of Gustav Lindenthal as bridge commissioner. (While Lindenthal was more than qualified for such a position, one suspects it served as consolation for Lindenthal’s beloved North River Bridge losing out to the tunnels.) “[Low] does know very well and intimately the Pennsylvania millionaires…and he plans to give them a perpetual franchise in New York City in defiance of existing laws.”

Newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst in 1904.

Young Hearst had confounded Gotham with his lightning rise to power. Armed with his family’s glittering mining fortune, he had stormed the New York newspaper world in the fall of 1895, hell-bent on trouncing publisher Joseph Pulitzer and displacing the World as Gotham’s and the nation’s leading Democratic newspaper and champion of the working people. At first, few took Hearst or his newspaper seriously. Plenty of better men had expended vast sums and failed to make a mark among New York’s crowded field of powerful newspapers. “Though he continued to dress like a dandy and live the life of a playboy, Will Hearst was, or believed himself to be, as authentic an advocate of the workingman as his rival,” writes biographer David Nasaw. “There was no blue blood in the Hearst family. While Will had been raised with a silver spoon in his mouth and gone to Harvard, he had never forgotten where his father came from…In New York, as in San Francisco, he ran a paper that was pro-labor, pro-immigrant, and anti-Republican.”

The paterfamilias, George Hearst, had been a barely literate scraggle-bearded miner savant, a self-taught geologist who roamed the West for years and struck one fabulous bonanza after another. His holdings were legendary: the Homestake gold mine, the Ontario silver mine, and the Anaconda copper mine, among others. The elder Hearst bought himself a U.S. Senate seat from the California legislature, served with no distinction in Washington, D.C., and died there in early 1890. Now his formidable widow, Phoebe Apperson Hearst, reluctantly doled out millions to her ambitious only child.

William Randolph Hearst swiftly showed he was very much a force to be reckoned with, a genius at journalism, promotion, and ballyhoo. From the start, the Journal American’s illustrations were extraordinary, while the news was always played to be as sensational as possible—blaring, eye-catching, a titillating mix of crimes and accidents, dirty politics, scandals, and his trademark crusading investigative reports. Hearst was fearless in taking on all the powers that be. With his daily paper (price: one cheap penny) gaining readers fast, Hearst next raided his targeted rival, the Sunday World, with its circulation of 450,000, dangling an irresistible salary before editor Morrill Goddard, a seasoned and brilliant newspaperman. Goddard was sorely tempted, but couldn’t bear to leave behind his carefully cultivated staff. Master of the grand gesture, Hearst expanded his offer to include them as well. Pulitzer, learning that Goddard had jumped ship, responded with a better offer. Goddard returned to the gold-domed Pulitzer Building. Hearst bid higher and “Pulitzer was left with an empty office and one stenographer,” writes Hearst biographer Nasaw. “Even the office cat, it was reported, had defected to Hearst.”

Nor was it simply a matter of money, though the ink-stained wretches of Park Row found man-about-town Hearst wondrously generous, a boss like no other, heaping bonuses on top of handsome salaries. Explains Nasaw, “Pulitzer had become an impossible man to work for, a nasty, vituperative, foul-mouthed martinet. [Now] Blind, and so sensitive to sound he had to eat alone lest he be disturbed by a dinner companion’s biting on silverware, Pulitzer had abandoned New York but had been unable to settle down anywhere else…Incapable of managing his papers at close hand, but unwilling to let go, he interfered at a distance.” Despite the mass defections and Pulitzer’s wretched health, the World remained a great populist paper, widely read and much admired. Now it was joined by Hearst’s even more fiery, far less admired, highly partisan and increasingly influential Journal American.

It would be almost a month before the PRR officials extricated the new improved tunnel bill from the state legislature, a bill specific enough in its detail to placate many of its critics on the Rapid Transit Commission. In this first round, Mayor Low had also quietly scored a crafty coup. Reported the New-York Tribune, “The Board of Aldermen will have no power to modify the grant or contract made to the Pennsylvania Railroad, but can either approve or disapprove the grant or contract, as they please.” With the franchise back on track, a manager from the PRR’s New York office ventured over to speak with S. S. Carvalho, managing editor of Hearst’s Journal American (and another Pulitzer alum). He reported back to Philadelphia with delight, “Mr. Carvalho assured me that he has great personal admiration for our Management, and asked me to say to Mr. Cassatt that no paper in the country is more friendly to the Pennsylvania Management than is the New York Journal. I have the assurance of Mr. Carvalho that…the Journal would not go out of its way to criticize or complain of matters in which our Company may be, hereafter, interested.” Whatever the reason for this abrupt change of heart, it was welcome news indeed.

It would take another two months of closed-door negotiations, but as summer neared, Mayor Low and the Rapid Transit Commissioners finally voted on June 15, 1902, in favor of the franchise, which would be perpetual. (It was perhaps not irrelevant that five weeks earlier Cassatt had decided the PRR did after all need the legal services of Platt’s lawyer son at $10,000 a year.) The franchise would also allow the PRR the all-important privilege of buying and closing the part of West Thirty-second Street that otherwise would run right through the proposed terminal. For these privileges, the PRR would pay $75,535 annually for a decade and then $114,871 each year for the next fifteen years, for a total of almost $2.5 million. Thereafter, the franchise fees would be renegotiated. The New-York Tribune marveled at “the almost boundless confidence of President Cassatt and his advisers in the future of this city, for the Pennsylvania is preparing to pour out money like water for the privilege of placing a station in the heart of the nation’s metropolis.”

In truth, Cassatt was miffed. In no other city in the world would a corporation pay to build a tunnel. In any case, the battle had taken more than three months. But Cassatt and his tunnel franchise had survived the first great test. At the end of the meeting, Cassatt rose, grinned happily, and shook hands with each and every one of the commissioners at the long wooden meeting table. Mayor Low deemed the agreement historic, being the first time that the “city has received such a large sum for a franchise.” Now came Tammany.

On Tuesday July 1 as the rain was clearing outside, the clerk serving the Board of Aldermen stood up in the pungent City Hall chamber with the PRR franchise in his hands and began to read it aloud, signaling its formal introduction. Many of the seventy-nine members were not present and those who were paid little attention, loafing about in their wooden swivel chairs, chattering and smoking instead among themselves. The suffragette Beatrice Webb had visited these very chambers several years earlier and been appalled by the aldermen, finding “one face more repulsive than another in its cynicism, sensuality or greed…The type combined the characteristics of a loose liver, a stump orator and intriguer with the vacant stare of the habitual lounger.” The reading clerk was only a sentence into his dronelike recitation of the PRR franchise when Alderman John Diemer, a clean-shaven gangly fellow, motioned him to stop and quickly consigned the document unread to the Committee on Railroads that he chaired. Ten days passed of what was turning into a rainy, cool summer, and there the tunnel bill languished.

New Yorkers watched with a sort of perverse pride as rumors wafted languidly forth from that ungracious civic body of aldermen indicating no hurry to proceed or likelihood of action. There were rumblings of unnamed “lobbyists” lining up to defeat the measure, of Tenderloin aldermen Reginald Doull and William Whittaker waxing obdurate because the terminal would displace vast numbers of their constituents. Most assumed that the Tammany aldermen were simply settling comfortably into their accustomed expectant posture, waiting to be “seen” (i.e., paid off), with the figure $300,000 whispered about. Alexander Cassatt, president of the wealthy Pennsylvania Railroad, could assert all he pleased, as the New-York Tribune reported, “that the company would not pay one dollar in order to get the franchise through the Board of Aldermen.” But why did that high-handed gentleman feel he or his project were any better than the rich and disdainful August Belmont and his Lenox Avenue IRT extension? Belmont had “seen” the aldermen to the tune of $20,000, according to the Trib and City Hall scuttlebutt. Gotham and Tammany had their own long-entrenched political folkways and there was no persuasive reason this corporate titan from Philadelphia should not honor them.

Repeatedly prodded by Mayor Low, the aldermen on the Railroad Committee finally bestirred themselves to consider the PRR franchise. And when they did, they found little to like. Proclaimed Republican alderman William Whittaker, “No vote of mine shall ever bestow a perpetual franchise of the city’s property above or below the streets and I warn the honorable Mayor and Rapid Transit Commissioners to flee from the wrath to come.”

Several demanded the franchise be recast to oblige the PRR to hew to the municipality’s own eight-hour labor and wage rules, despite court verdicts against such rules for private companies. Otherwise, prophesied Alderman Doull, “scab labor would be brought from Pennsylvania to build the tunnel under charge of padrones.” They also complained that the franchise compensation was mingy; the city should have some control of the actual tunnel; it was all a plot to divert the city’s immense freight business out to Montauk. One alderman idly wondered why the city didn’t build the tunnels itself? When the franchise was sent out to the full chamber on Monday July 21, the aldermen vented their ire by voting it down 56 to 10 and scornfully tossing the whole matter back to the Rapid Transit Commission.

The conservative press howled, denouncing “The Short-Sighted Aldermen” and wondering “What Are Their Reasons?” The Commercial Advertiser assumed “blackmail” and lamented the defeat of a “Great public improvement…of vast and enduring benefit to the whole city.” Even Joseph Pulitzer’s staunchly Democratic World heaped contumely. The purported objections—franchise terms, labor issues—were “Worse Than Silly.” “It is a veiled ‘hold up,’ and the veil is thin.” Hearst, who was now hoping for Tammany’s backing for a congressional bid, took a tempered stance: “Let us give credit for common honesty to the men we elected, until they are shown to be unworthy, anyhow.” Mayor Low assumed a statesmanlike tone, reassuring the public that the aldermen’s action was “straightforward and manly” and that the Rapid Transit Board would “try to meet the criticisms of the Aldermen as far as practicable.” Low gathered a handful of the more important irate aldermen on his yacht Surprise the following warm Saturday to cruise about the harbor and soothe their ruffled feathers and talk some sense. Perhaps he thought the sight of all those jammed ferryboats crisscrossing the busy waters might instill some small feeling of civic obligation.

As August rolled around, anyone who could escape to a resort had fled. President Roosevelt was out at Oyster Bay, Long Island, mixing his vigorous idea of relaxing with politics. Brother-in-law Douglas Robinson summed up “the true Roosevelt style” as “going it with a vengeance…not a minute unemployed eating, talking.” But despite the president’s busy frolics and fun with his brood of children, he was growing increasingly worried about a spreading coal strike. Alexander Cassatt had headed north with his family to the cool days and evenings of Bar Harbor, Maine. Mayor Low remained dutifully in Gotham, doggedly persevering on the PRR’s behalf. In the muggy heat, even the trees looked exhausted, while the baking streets exhaled a sour stench. Men wore their straw boaters and cooler linen suits, while women in the popular white Gibson Girl dresses used parasols against the sun. On Sundays, hordes of cyclists clogged the avenues heading out of town. The city’s frenetic pace slowed. The street vendors offered ice cream and lemonade.

At City Hall, Mayor Low presided over a joint meeting of the Rapid Transit Commission, the Board of Aldermen, and the PRR. Everyone shifted about uncomfortably in the stifling meeting room, and the same aldermen stood up to complain once again about labor, the perpetual franchise, and the railroad’s intentions. Hot and bored, the PRR’s elegant vice president and attorney Captain John Green, a veteran of Sherman’s March, finally lost all patience. A slight, wiry man with a bushy gray beard, he had a prickly temper. When one alderman spun a dark vision of the PRR making Montauk a great port at New York’s expense, Green exploded, “No sane man ever thought or dreamed of taking commerce out to Montauk Point. You could no more take commerce away from New York than you could take blood out of your body and live. Montauk Point will never be a terminus. It is absurd even to discuss it…There is no more chance of the Pennsylvania Railroad doing that than there is of my flying over a house.”

And, reiterated Captain Green for the umpteenth time, various court rulings forbid requiring eight-hour labor and prevailing wage clauses in such a franchise. Moreover, the PRR prided itself on good relations with its workers. “We always pay him well.” At the end of the session, Green wearily repeated, “We have come here with clean hands and asked for a franchise which it will be to your advantage to grant…We propose to spend $40,000,000 to $50,000,000 and propose to observe the law.” Translation: No boodle. To Cassatt, he complained, “Had to listen to two hours of blatherskiting.”

And so summer drifted into a lovely autumn, and week after week there was a franchise parley here, a minor concession there, but no sign of progress. It was, it seemed, a season for standoffs. Down in Washington, D.C., President Roosevelt was yearning to somehow end what had become a rancorous and potentially devastating Pennsylvania coal miners strike. The 147,000 striking anthracite miners—mainly Slav immigrants—displayed an evangelical fervor, swearing off liquor, smoldering in their determination to wrest better pay and union recognition. The cartel of coal mine and railroad operators who controlled this all-important industrial and domestic fuel were equally adamant, refusing to so much as meet the miners or United Mine Workers president, John Mitchell. Mine owner and railroad president George Baer pontificated, “The rights and interests of the laboring men will be protected and cared for—not by the labor agitators, but by the Christian men to whom God in His infinite wisdom has given the control of the property interests of the country.” This produced great brays of derision in even the most conservative of journals.

But the coal strike was no joke. If the two sides did not come to terms soon, how would the great cities heat themselves? Or the nation’s steam engines run? Even were the strike to end instantly, the nation was already ten million tons short. Now the eighteen thousand bituminous miners had joined in, thus forcing the layoffs of the fifty thousand men running the labyrinthine system of coal railroads. Moreover, what was now the biggest organized strike in the nation’s history was flaring into violence just as the nights were growing noticeably colder. Lacking any real authority to intervene, Roosevelt wrote Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, “I am at my wits’ end how to proceed.” When fall frosts shimmered on chill mornings with their intimations of winter, the president became desperate and summoned the two stalemated sides to meet October 3 in Washington. The mine owners came but arrogantly spurned all compromise.

In Manhattan, the PRR tunnel franchise languished at the Rapid Transit Commission while Mayor Low valiantly sought allies among the aldermen. Complicating the entire bogged-down process was Tammany’s own summer of turmoil. Boss Richard Croker had, after two decades of corrupt power, partially ceded his tarnished throne. In these months, many vied for that prize, including Alderman Timothy P. Sullivan, a burly saloonkeeper who declared himself staunchly against the franchise unless there was a labor clause. In response, the PRR again cited Court of Appeals rulings that declared such a clause illegal. Week in and week out the PRR engaged in franchise parleys, making minor concessions here and there. Yes, the city could put police and fire phone and telegraph wires in the tunnel, yes it would be under the city’s police laws, and so forth. Meanwhile, the public charges of “hold up” grew clamorous.

Determined to move things forward, Mayor Low turned up the pressure and placated critics by holding another public hearing on the afternoon of Thursday October 2 at the commission offices at 320 Broadway. As soon as he learned of it, Cassatt sat down at his desk at Cheswold, where the meadows were full of autumn wildflowers, to quickly write for help from one of the grand old men of New York public life, former mayor Abram S. Hewitt. Would he testify for the PRR? “It is asking very much, I know, but your publicly expressed approval of the terms of the franchise would be of the greatest service at this juncture.”

Hewitt, a Democrat and self-made man who had also wisely married a wealthy heiress, was a known antagonist of Tammany. His unlikely 1886 mayoral candidacy had been a desperate and successful ploy to defeat the popular radical reformer Henry George. But once in office, Hewitt dropped Tammany and refused to have any truck with the Tiger, culminating in his refusal to fly the Irish flag at City Hall on St. Patrick’s Day. Hewitt, who had gone on to serve five terms in Congress, was also much admired for being the original and visionary proponent of underground rapid transit subways, now finally under construction.

By the fall afternoon of Low’s public hearing, the Pennsylvania Railroad’s long-stalled tunnel franchise had become a cause célèbre. Crowds of property owners, aldermen, politicians, lawyers, and labor leaders jammed into City Hall’s elegant wood-paneled meeting room, spilling noisily out into the hall and filling the curved upstairs gallery. In the tortuous eight months since Cassatt’s initial meeting with the mayor, the whole city had had ample opportunity to take sides. Soon, the cigar smoke grew thick, the room warm with too many bodies. The venerable Hewitt appeared for the Chamber of Commerce to laud the PRR, exclaiming over the “miracle…of connecting our shores with New Jersey. I myself never expected to see the day of the problem’s solution.” Restive labor elements in the audience heckled and jeered: “Listen to him!” “Let him sell the city!” “Let ’em build by divine right!” Tammany had cast itself as the great champion of labor in yet another chapter of the acrimonious battle between capital and labor. In Pennsylvania, the coal strike was growing ever more tense. Here in Gotham, thirty-five labor unions—having failed to secure the eight-hour wage clause—remained staunchly antitunnel.

As the light outside waned, William Baldwin, ever the reformer, presented the PRR as that rare benevolent and honest road: “It has made its proposition with the higher sense of duty to the public. The Pennsylvania Railroad does not object to union labor…This corporation is offering to build the tunnel not simply to make money for itself, but because the people want the tunnel. And the people will have it!” Mayor Low hoped all this hostile venting, plus the ardent endorsements by merchants, business interests, and the press would do the trick. And indeed, within the following week, the Rapid Transit Commission had once more passed the revised franchise and sent it over to the aldermen. Growled the New York Times, “Public opinion…will not patiently tolerate any trifling with the matter.” Meanwhile, the PRR had bought so much of the needed real estate that the interest alone was now a thousand dollars a day, making the foot dragging rather pricey.

As October passed, the Tammany aldermen professed to be far too busy with upcoming November elections to take up the franchise bill. Great trainloads of Tammany men had headed north to their nominating convention, where William Randolph Hearst was backed as a Democratic candidate for Congress from an east side district.

In Washington, President Theodore Roosevelt was grimly contemplating the worsening debacle of the United Mine Workers’ coal strike. Seven men were dead in angry clashes. Winter was looming, anthracite had skyrocketed to thirty dollars a ton, and anxious memories hovered of the anarchic Great Railroad Strike of 1877. If the pigheaded operators did not come around soon, Roosevelt intended to order the army reserve to seize and reopen the Pennsylvania mines. To forestall such an unheard-of federal assault against capital, J. Pierpont Morgan stepped in. As a major coal road stockholder, a glowering Morgan managed to cajole the haughty mine owners into submission. By October 15 they had agreed to a face-saving commission to accompany the reopening of the mines. The Coal Commission hearings shocked the nation, with revelations of child labor working night shifts in the mines. The Hearst papers dubbed the mine owners, “The Dollar-Rooting Swine of the Anthracite Fields.” The miners won most of their not-unreasonable demands. The president was jubilant at the settlement, declaring he felt “like throwing up my hands and going to the circus.” For the first time, an American president had given equal weight to both sides when he intervened in a bitter labor struggle. Like Cassatt, Roosevelt feared the consequences of corporations refusing to fairly reward the working man.

Mayor Low lacked the president’s power and only the incessant clamoring of the New York press caused the Board of Aldermen’s Railroad Committee to set a hearing date on the tunnel franchise. On Wednesday November 26, five hundred people mobbed the wood-paneled City Hall hearing room. Reform and Tammany politicos traded bitter and passionate jibes with the silk-hatted merchants, while the ranks of labor engaged in such loud booing and hissing that Chairman Diemer had to pound his gavel violently to bring order. Hour after tumultuous hour, one side—“the railroad interests, the Rapid Transit Commissioners and the great commercial associations”—sang the praises of the great tunnels and terminal, while foes—“united labor”—hectored on about the lack of a labor clause (“If this rich corporation wants the tunnel, let them agree to pay…$2 a day for eight hours work”), insufficient payment for the franchise privilege, and the general chicanery of the corporations. Alderman Reginald Doull alone occupied thirty minutes ranting, as was now his wont, about the PRR’s “trickery and bribery” in buying up so much of his district. When the session finally dragged to an end after five dispiriting hours, lower Manhattan was dark and oddly quiet, for the working world had long gone home to prepare for Thanksgiving the next day. The PRR’s fourth vice president Samuel Rea told a reporter, “I am sure that the pride of this community and the enterprise of its citizens will not allow us to abandon the tunnel.”

The PRR was growing weary of this stalling and John Green, third vice president, told one reporter as he departed, “If we don’t get permission within the next twelve months to build the tunnel we will abandon the whole enterprise and sell the real estate we have already bought. We can do that without any trouble. We have received offers for it.” Once again, the Tribune boldly warned of a “clique…determined to extort from the Pennsylvania company a round sum for the tunnel franchise,” hiding behind a sudden “love for the cause of labor.” The figure of $300,000 remained the purported sum. Alexander Cassatt reiterated, “We have come to New York for this franchise with clean hands, and we are going to keep our hands clean. We will not pay one cent for the granting of this franchise beyond the terms stated in the proposed contract.”

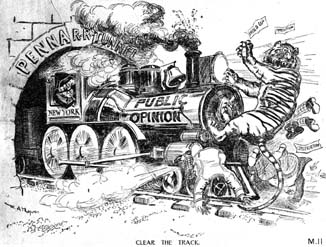

With the bill still mired in the Railroad Committee more than a week later, the World ran a big front-page cartoon on Thursday December 4 featuring a hungry Tammany Tiger holding an empty, open “dough bag,” its large paws pinning down the PRR franchise legislation. Lounging about were a handful of cigar-smoking politicians complaining, “Nawthin’ in it for us!” The accompanying story, titled “Ugly Rumors of Boodle,” spoke darkly not just of the usual bribery but of “powerful interests” out to thwart the PRR’s entry into Manhattan. The talk of defeat intensified. The next day Manhattan had its first snowfall and the temperatures began to plummet. Within days it was so bitterly cold, the aldermen voted $100,000 in free coal for the poor in their frigid tenements. The harbor began to clog with ice, forcing the ferries to struggle across, a potent reminder of the dire need for tunnels.

Every important Gotham newspaper and magazine (save Hearst, who had just won a congressional seat with Tammany backing) had joined in a prolonged and collective howl of high dudgeon and outrage. The New York Times denounced the aldermen as crooks: “There is not an honest hair in the head of one of them.” Scientific American excoriated the aldermen for “one of the most shamefaced exhibitions of political tyranny that ever disgraced the city of New York.” Letter writers hurled contempt, lamenting “the shameful spectacle” and castigating the aldermen as “a perpetual menace to good government.” By December 9, the much-abused Railroad Committee at last disgorged the franchise bill to the Board of Aldermen.

Now the serious arm-twisting and vote counting began, with every paper running detailed lists of which aldermen were For, which Against, and which In Doubt. The “Easy Boss” declared from the fastness of the Amen Corner that every one of the fourteen Republican aldermen would faithfully vote for the franchise, as his party did not want any responsibility for “defeat of a measure of such vast importance to the city.” Senator Platt and others further warned that should Tammany fail to do right, they intended to sidestep them via legislation in Albany. Governor Odell, ever hostile to Platt, disputed this claim. Charles F. Murphy, the wealthy owner of four saloons who had beaten out Tim Sullivan for the Tammany leadership, claimed neutrality, but few believed him.

In its December 12 issue, the Railroad Gazette marveled that “every daily newspaper in New York” endorsed the franchise. “Public opinion is overwhelmingly in favor of what is unquestionably one of the most valuable public improvements ever devised for the city. This nobody questions, but the franchise is held up by a band of political buccaneers…It is hoped that…a few of those who now oppose the franchise will come to their senses.” The early perverse civic amusement at Tammany’s greedy antics had given way to sober concern that the PRR’s marvelous enterprise, this $50 million private solution to water-locked Gotham with its forty-one ferry routes, might actually be rejected. And so petitions in the tunnel’s favor began inundating the aldermen. Great department stores like R. H. Macy & Co. and Saks & Co., leading hoteliers from the Waldorf-Astoria, the Delavan, and the Navarre, real estate companies with major holdings, even fifty-two labor unions beseeched the dilatory aldermen “not to deprive New York City of this great project.” But Tammany’s “Little Tim” Sullivan insisted that he and forty-three of his political Myrmidons intended to do just that. They had the votes and they would vote nay. “No power on earth can deliver me into the hands of the Pennsylvania Railroad,” he vowed.

On Tuesday December 16, Gotham was swathed in light snow from a furious weekend nor’easter. Now, the skies were an iridescent blue, but a bone-chilling damp encased the city. Coal shortages plagued the slums. The city’s bedraggled, bundled-up shovel brigades shuffled and scraped as they cleared the streets and sidewalks, dumping the snow into horse-drawn carts for disposal in the river. It had been an exasperating year since Alexander Cassatt had first announced the PRR’s tunnels and terminal project.

Finally, on this freezing wintry day the full Board of Aldermen would determine the PRR’s fate. All Gotham was abuzz over this high-stakes cliff-hanger, the final act in the rare spectacle pitting Alexander Cassatt and his unusual ethos of corporate honesty versus the entrenched grafters of Tammany Hall, holding out for their $300,000. The Journal American had reported a week before “the presence of Mr. Patton, President Cassatt’s right-hand man in this city for a few hours…His movements could not be traced, but it was understood that he had given assurances [to key aldermen], in nowise connected with the payment of money.” In an era of flagrant bribery and boodle, the Railroad Gazette praised the PRR simply for being honest and thus “an example to other corporations…And there has been no retreat, no dickering and no serious concession.” The tunnel bill needed 40 votes to pass. The newspapers listed only 22 aldermen willing to go on record thus far as yeas. This was certainly an improvement over the board’s original dismissive vote of 10 yeas and 56 nays, but it was no winning number.

And so, once again, the aldermanic chambers and galleries were jammed with spectators, a shifting sea of black derbies and silk top hats, all anxious to witness and influence this historic clash. At 2:07 p.m. on December 16, the session was gaveled open. Mayor Low had dispatched to every member of the “honorable board” (and the city press) a heartfelt letter, pleading with them to consider the monumental importance of the tunnels. “It means, if accepted, more work for the laboring man of New-York, not only during the process of construction, but also through the centuries of the railroad’s operation; it means more business for our shops, more employment for our factories, and more commerce for our port; and it means cheaper and better homes within the borders of our city for multitudes of our population. It will go far to make sure of the permanent pre-eminence of New-York among the cities of the world.”

The first order of business was a full reading of the Railroad Committee’s favorable report. Then two antis stood up to deliver cantankerous reports against the tunnels and the PRR. Alderman Moses Wafer proposed consigning the franchise once again to the Railroad Committee. The first moment of truth had arrived, causing a ripple of excitement in the galleries. A dozen aldermen scurried out of the chambers to avoid casting votes, while those remaining strutted and speechified at length before voting yea or nay. It was perilously close, but the PRR won 35 to 32 on this issue of consignment. The franchise would be voted on this afternoon. Such was the importance of this vote, that all but one (out ill) of the seventy-nine aldermen were present.

For four tense hours discussion dragged on, “during every minute of which there was constant effort being made by the opponents and friends of the franchise to win votes.” There were small surprises, as when a Tammany man, Frank Dowling, stood up to say, “If you pass this tunnel franchise, it is in the interest of labor…If it is a crime to give people work, than I am going to commit that crime.” Finally, as six o’clock approached, the roll call began. Again, numerous aldermen exited. Of those present, only 33 voted yea for the franchise, while 28 voted nay. (It was a reflection on Boss Platt’s waning powers that four Republicans were among the nays.) Some of the absent Tammany men reentered the chambers. Two voted yea. Bronx Borough President Haffen, who hurried out to take a telephone call, returned scowling. As he conferred with other Bronx men a rumor raced through the chamber that Charles F. Murphy, who had emerged as the new boss of Tammany, had called to order Haffen to vote nay. But an angry-looking Haffen, suffering from a cold and sore throat, stood up and croaked his vote yea for the tunnels. At that, a Brooklyn alderman rushed over to change his yea vote to nay. Slowly, one after another, Haffen’s Bronx Democrats followed their leader, and the vote for the tunnel franchise crept slowly up to 39.

At six o’clock when yet another Bronx Democrat stepped forward, the crowd quieted. That alderman looked around and voted yea, making 40 votes, exactly the number needed for passage. The chamber exploded in a rollicking roar of applause, groans, and hisses. The public reaction was jubilant. More than a year after Cassatt had first announced his tunnels, the PRR had their franchise and they had paid no boodle. “The great thing,” wrote the New York Times, “the momentous thing, is that the way is now open for the Pennsylvania Railroad to begin work upon the tunnel and terminal.” For the PRR men, all the earlier frustrations and postponements and the failure of their North River Bridge plans could now be forgotten. They could luxuriate instead in the knowledge that their railroad would come into Gotham. Down in Philadelphia, Cassatt emerged from a Union League dinner smiling broadly, “It looks like clear sailing now.” He would need every ounce of that optimism for the travails ahead.

A political cartoon about the tunnel franchise fight.