TWENTY-SIX

CODA

Alexander J. Cassatt and Charles Follen McKim had bequeathed to Gotham a magnificent monument in Pennsylvania Station, drawing inspiration from one great and ancient empire to create a modern temple of transportation worthy of their own ascendant American empire. Perhaps no one ever captured so beautifully the timeless essence of McKim’s architectural masterpiece as did Thomas Wolfe in his novel You Can’t Go Home Again, published posthumously in 1940: “Few buildings are vast enough to hold the sound of time…. There was a superb fitness in the fact that the one which held it better than all others should be a railroad station. For here, as nowhere else on earth, men were brought together for a moment at the beginning or end of their innumerable journeys, here one saw their greetings and farewells, here in a single instant, one got the entire picture of human destiny. Men came and went, they passed and vanished, and all were moving through the moments of their lives to death, all made small tickings in the sound of time—but the voice of time remained aloof and unperturbed, a drowsy and eternal murmur below the immense and distant roof.”

And yet all of Penn Station’s monumental grandeur could not compensate for certain intrinsic problems. When an ailing James McCrea retired early on November 13, 1912, Samuel Rea ascended to the presidency of the Pennsylvania Railroad still engaged in a herculean—but as yet futile—struggle to secure a West Side subway line for the station. If it were not so galling, it would be almost funny that in 1917, four and a half years later, Penn Station could boast a more convenient connection to Boston than it had to other parts of New York City. On March 9, 1917, Rea and Gustav Lindenthal dedicated the final piece of Cassatt’s dream, the Hell Gate Bridge across the East River (at 1,017 feet the world’s longest steel arch bridge) from Queens to Ward’s Island, thus completing the PRR’s New York Connecting Railroad to New England. On this red-letter day, the Seventh Avenue IRT was still not finished. Not until the next year, 1918, could passengers debarking LIRR and PRR trains finally step onto a Seventh Avenue subway from a Penn Station stop—sixteen years after Cassatt and Rea first requested such service and eight years after the station opened. So convoluted were New York subway politics, it would be yet another decade before the Eighth Avenue subway finally connected to Penn Station.

Samuel Rea (right, in derby) and Gustav Lindenthal (left, white hair) dedicate the Hell Gate Bridge March 9, 1917, thus completing the New York Tunnels and Terminal Extension begun in late 1901.

Not only did this early lack of real mass transit undermine the success of Penn Station, so did its inauspicious location. The Tenderloin neighborhood was no longer the raucous Satan’s Circus of old, but enough saloons, dance halls, and bordellos lingered on to make those West Side blocks seedy. When Rea tried to recruit real estate developers to upgrade and beautify Penn Station’s immediate vicinity, he was told by one realtor, “It is not a question of more transportation facilities (though these are always helpful) as much as the purifying of the neighborhood by the occupancy of the streets by respectable people doing business or living in hotels there.” Another potential developer pointed out to Rea that his own passengers did not care to linger in the vicinity, preferring to “take cars and escape almost as if the station were in a plague spot.”

Unfortunately, the top PRR brass, being largely Philadelphians, failed to grasp that they would have to boldly lead the way as investors and even builders to transform the neighborhood into a worthy setting for their New York station. True, the PRR had, albeit with considerable difficulty, wooed the U.S. Post Office to build atop their tracks on Eighth Avenue. McKim, Mead & White’s attractive Corinthian temple, the new main branch of the New York Post Office, opened in December 1913. A quote from Herodotus about Persian couriers chosen by the architects and inscribed on its Eighth Avenue frieze soon became the agency’s unofficial motto: “Neither snow, nor rain, nor heat, nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.”

Cassatt and Rea had always envisioned their Pennsylvania Station as the catalyst for a neighborhood real estate boom: modern office skyscrapers rising on avenues busy with important men wearing top hats, fancy hotels and theaters displacing saloons, and smart shops, boutiques, and bustling cafés giving new polish to nearby blocks. They had hoped to see the city widen Seventh Avenue, along with Thirty-Second Street, creating a handsome plaza. But the PRR failed to control the requisite sites and Tammany, which still ruled Manhattan, was not about to bestir itself for corporate foes. Two years after the station opened, the Seventh Avenue Improvement Association complained that the PRR itself was stymying new development. Their overpriced and unsold holdings were sitting “vacant or covered with old rookeries…In the meantime the section south…was being built up as a loft or factory section. If the present situation continues, factory building will gradually close in on the station. When this happens Mr. Cassatt’s dream will have failed…For want of investing $10,000,000 or $15,000,000 of additional capital the Pennsylvania Railroad is impairing the value of the $125,000,000 already invested.”

To its great and lasting detriment, as art historian Hilary Ballon writes, “The Pennsylvania did not see itself in the business of real estate development. Its business was the railroad.” Consequently, this rich and powerful corporate giant had not gained possession of sufficient adjacent territory—as had the Vanderbilts and New York Central around their terminal—nor did the PRR officers have the mind-set to aggressively and strategically use what they did own to reshape the surrounding district. As one developer upbraided Rea, “I find my endeavors thwarted at every step by the constant opposition of my [real estate] clients, because of your apathy as compared with the zeal and activity of the New York Central people.”

Finally, desperate to demonstrate their support for desirable buildings, the PRR helped underwrite the Hotel Pennsylvania, a comfortable business hotel that opened directly across from the station’s Seventh Avenue entrance, but not until January 1919. The 2,200-room hotel, also designed by McKim, Mead & White, became the city’s largest hotel, but possessed no great cachet. It was the PRR’s first and last foray into active development. Between the late arrival of the IRT subway and the even later opening of the Eighth Avenue IND, the seedy character of the nearby streets, and the timidity of the PRR’s own efforts, the blocks and avenues around Penn Station languished. No fancy skyscraper office buildings arose, nor fashionable hotels. The Penn Station neighborhood remained a disappointing backwater.

As for Penn Station itself, New Yorkers harbored mixed feelings. They adored its glamour and grandeur, the sense it gave one of embarking on a magnificent journey. They loved the convenience of catching the all-Pullman Broadway Limited to Chicago or the Orange Blossom Special to Florida right from Manhattan, as well as the prospect of glimpsing a star like Charlie Chaplin or political bigshot being squired about by Stationmaster Egan, jovial and elegant in his top hat, gray spats, and trademark mahogany cane. (Reportedly, “Mr. Egan was the only man with whom the late President Coolidge ever spent three hours chatting.”) Travelers felt part of something momentous just by entering the station, important players in the great human drama.

The Hotel Pennsylvania being built across Seventh Avenue from Penn Station.

Amidst the crowds surging through McKim’s General Waiting Room, wrote Thomas Wolfe in You Can’t Go Home Again, “There were people who saw everything, and people who saw nothing, people who were weary, sullen, sour, and people who laughed, shouted, and were exultant with the thrill of the voyage, people who thrust and jostled, and people who stood quietly and watched and waited; people with amused, superior looks, and people who glared and bristled pugnaciously. Young, old, rich, poor, Jews, Gentiles, Negroes, Italians, Greeks, Americans—they were all there harmonized and given a moment of intense and somber meaning as they were gathered into the murmurous, all-taking unity of time.”

For some New Yorkers, the glamour and rich human theater were offset by the station’s shortcomings. “The average traveler will be dumbfounded when he views the magnificent waiting room and concourse for the first time,” wrote railroad man John Droege in 1916, “but in more cases than a few the immensity of things and the magnificence will lose their luster when he has traversed the ‘magnificent distance’ from the sidewalk to the train or vice versa. It cannot be denied that this is a disadvantage.” This criticism struck such a nerve at the PRR that, true engineers that they were, they assembled detailed statistics on walking distances at numerous major train stations—including Grand Central Terminal—to prove that walking a thousand feet to catch a train at Penn Station was no worse (or not so much worse) than elsewhere. Another longstanding gripe among the natives was “The ambiguity of the many exits from the trains, some leading to the second level and some to the third.” This, wrote architecture critic Lewis Mumford, “is baffling to anyone attempting to meet a person arriving on a train.” Over the years, the PRR continually adjusted the station—making platforms longer, installing escalators—including one right up the center of the Grand Stairway. But they never really addressed these principal design flaws.

The General Waiting Room in 1930.

Ironically, the Long Island Rail Road, something of a stepchild in the original enterprise—it was allocated five of the station’s twenty-one tracks in 1910—turned out to be the more important source of passengers. In 1911, the first full year of operation, the LIRR carried six million riders. LIRR President Ralph Peters reported that in one year 7,793 houses were built along their lines in Queens and Long Island, forty factories, 773 stores, and 792 other buildings. By 1917, the number of LIRR riders had doubled to twelve million, making them two-thirds of Penn Station’s eighteen million annual passengers that year. The preponderance of suburban commuters at Penn Station was not just unanticipated, it was “a problem because the station, from track layout to support spaces, was not designed to serve commuter traffic. The large majority of users were confined to cramped quarters. They moved underground, from commuter shuttles to subways and streets, without cause to enter McKim’s uplifting vaulted spaces. Millions of people were using Penn Station, but not as McKim had intended and, more urgently, not as the Pennsylvania Railroad projected on their balance sheets.”

Moreover, Penn Station had been built to handle far greater numbers—a hundred million people a year—than the eighteen million being served in 1917. Consequently, President Rea found himself once again defending the whole Gotham enterprise from attacks: “The Pennsylvania Station,” he wrote, “instead of being a monument to inefficiency and waste and a white elephant, is a monument to foresight and the necessities of New York City and the whole country with which it does business…The station was constructed for the future.” Two years later, in 1919, Penn Station’s passenger numbers had almost doubled to thirty-four million, surpassing Grand Central Terminal, and vindicating the PRR’s belief that ever larger numbers would flow in and out of the nation’s greatest city.

On September 30, 1925, at Broad Street Station in Philadelphia, Samuel Rea, still tall and commanding, but more heavyset, his thick shock of hair almost white, walked into the opulent wood-paneled meeting room of his road’s board of directors, with its oriental carpet and carved mantel. Oil portraits of the previous eight presidents (all deceased) kept corporate vigil. The gathered directors no longer sported the fussy dark frock coats, high white collars, and silk cravats of old. The new corporate attire was the modern business suit, vest (with watch and chain), and tie. Outside, under a gray sky, the powerful locomotives screeched and rumbled as they came and went. How many times had Rea come into this room, suffused with the railroad’s history and so many memories of his own? Just nine days earlier Rea had celebrated his seventieth birthday and today he would officially retire. The previous April, Rea had given his valedictory speech to the shareholders at their annual meeting in the grand foyer of Philadelphia’s Academy of Music. On that occasion, Rea lamented that “We have had a continuous struggle to prevent the confiscation of the railroad investment and service by unwise, wasteful and hostile legislation and regulation which, happily, a fully informed public opinion has tempered.”

Today when he retired, as called for in the company rules, Rea would become the first PRR president ever to reach three score and ten and to leave this famously “killing” job in good health. His was a true Horatio Alger story, from humble beginnings fifty-three years earlier as a rod and chain boy to the twelve years he had just completed as the activist ninth president of the company. This had made Rea one of the nation’s most powerful men, for his railroad employed 165,000, carried an eighth of the nation’s freight, transported sixty-seven million passengers, and was valued at $136 million. And yet, marveled the Wall Street Journal, Rea possessed an “almost singular combination of modesty, steadfastness and unselfishness.”

Today was, of course, a day of sentiment and praise. The board of directors, arrayed around the highly polished doughnut-shaped wooden meeting table, honored Rea’s role as the steady guiding hand behind the New York Extension by voting to engage artist Adolph A. Weinman to create a second monumental bronze statue for Penn Station. This one would be of Rea and occupy the niche across from Cassatt. Back in March 1911, Rea had rejected a proposal to place a statue in that niche that would honor the project workmen who had perished, along with a plaque listing their names. No explanation was given. Perhaps he did not feel the sandhogs and other laborers merited the honor. Perhaps he preferred not to dwell on those who died building the company’s great work—because his own son had been among them. Rea’s wife, Mary, still wore black mourning. Or perhaps he felt the honor should be his, for he had been Cassatt’s right-hand man for the first five years and then seen the project through its darkest hours.

In the fifteen years since Penn Station had opened, there had never been any detailed public discussion of what had inarguably been the most anguishing struggle of Samuel Rea’s career: his decision—against the advice of three of his own outstanding engineers—not to attach screw piles to the North River tunnels. Time had borne out the wisdom of Rea’s choice, for the tunnels—constantly surveyed and watched—had proven to be completely safe. They had not, as had been Rea’s worst fear, continued to sink inexorably deeper and deeper into that ancient silt or shown any sign of strain. Instead, as the PRR’s own meticulous measurements showed, the tunnels continued to oscillate very slightly with the tide of the great river that flowed in and out high above them.

Like Rea, the North River tunnel engineers viewed that work as the highlight of their careers, a project of such magnitude and importance, so fraught with travails and triumphs, that they hated to part. And so, under the aegis of the Pennsylvania Tunnels Alumni Association of the North River Division, for years they threw merry, elaborate reunion dinners at Healy’s Restaurant on Columbus Avenue. Menus featured “Chicken Gumbo à la Terminal West” and “Grapefruit in Half Section apparently severed by some sharp instrument.” In the early days, Charles Jacobs and James Forgie had presided at these jolly soirees, winding up after many courses and cocktails, Roman punch, and other libations, singing the many verses of their own sentimental anthem, “Tunnel Days.”

The PRR board of directors was looking on this September day not just to the past, but to the company’s future. With Rea’s retirement, they elected W. W. Atterbury tenth president of the PRR. Promoted not quite three decades earlier by Cassatt to unsnarl Pittsburgh, Atterbury over the ensuing years had demonstrated great range and charm as an executive. Having started as a three-dollar-a-week shop apprentice, Atterbury prided himself on cultivating the best in everyone he worked with. During World War I, he had served in France, constructing railroads almost from scratch for the Allies and then running them, earning the rank of brigadier general. Today, Atterbury expressed his considerable pleasure at becoming president, saying, “I like to think that the Pennsylvania railroad has a soul and that its soul has been created out of the lives of men who devoted themselves to its service…the Pennsylvania Railroad has a great destiny.”

In a final gesture of appreciation to Samuel Rea, Effingham B. Morris bestowed upon the retiring president a personal gift from the board of directors, rare English silver plate made in London in the reign of Charles II. This was a most apropos memento because Rea, who so loved history, confessed “a weakness for studying old English silver craftsmanship and its distinctive hall marks of which there is a record for about six hundred years.” Further, he savored “the pleasure of constantly using these works of art.” During his presidency, Rea, now wealthy, had built a beautiful fieldstone mansion on 104 rolling acres in Gladwyne. He named this graceful Main Line estate Waverly. “Tramping and working about my home farm give me all [the exercise] I need,” he said during one interview, with wood chopping a favorite activity. Now, Rea looked forward to having more hours for tending his peach orchards there.

Whenever Rea spoke with reporters, he never wavered in his advice for the young and ambitious: Read! Books, especially biography and travel, he said, “give us insight into the lives of successful men and heighten the imagination and increase knowledge of other countries. If neglected by the young businessman, he will find himself lacking in culture, vision and balance of life. His sympathies will be narrow and selfish. He must stand for the best things in life and use his service, influence and money to advance them. The world gets nowhere with stand-patters or indifferent people.” A few years later, on March 24, 1929, Samuel Rea—who had thrown himself into Al Smith’s unsuccessful White House campaign the year before—died at home from a heart attack after a bout of the flu. He had believed deeply in his railroad and his country, and had relished working with the giants of his day, ushering in the astounding prosperity of the industrial age. He had outlived not just Cassatt, his revered boss, but also Charles Raymond, dead in 1913, Alfred Noble, who died a year later, and Charles Jacobs, who died in 1919.

Rea was a famously modest man, but it certainly would have pleased him to see the more than a thousand people gathered in Penn Station’s General Waiting Room on April 9, 1930, a fair spring day, for the unveiling of his statue. Even as crowds of passengers streamed by the Pennsy men commanding the Grand Stairway, great shafts of light illuminated McKim’s timeless space and organ music swelled up, deep notes slowly floating through the air. George Gibbs and Gustav Lindenthal, grayer, older, stouter, were both present, the sole remaining members of the original board of engineers. After a few words, they did the honors, pulling the cloth cover off the statue of their old boss and friend. Weinman had done Rea full justice. The sculpted Rea, wearing a modern business suit, overcoat draped over his left arm, fedora hat in hand, looked as vigorous in bronze as he had in real life. In his niche, he appeared to have just stepped in to look over the situation at the station. Like Cassatt, Rea was identified as an engineer by the blueprints clasped lightly in his right hand. The face was intelligent, considering. Two decades had passed since the unveiling of Cassatt’s statue on that hot August day in 1910. At that original ceremony, all the men then present could only marvel at the power of the Pennsylvania Railroad, the triumph of its entrance into New York, its radiant prospects.

The mood today was far more elegiac. The nation was mired in a wrenching Depression, hard times such as had not been seen in decades. But the greater melancholy was that Samuel Rea and all those present had lived long enough to know that the glory days of the Pennsylvania Railroad and every other American railroad were over. Back in 1906, when Alexander Cassatt had bucked all his peers in supporting President Roosevelt on railroad regulation, he thought it a sensible way to deal with their competitors—other railroads. But now there were different competitors, and they were not shackled by regulation. “The ICC,” writes business historian Robert Sobel, “improvised, temporized, mediated, and in the end acted in such a fashion as to leave the industry starved for capital and on the defensive, at a time—on the eve of the automobile and aviation ages—when massive funding was necessary for improvements.” Shortly after Rea’s death, a survey of regular PRR passengers revealed their own declining opinion of “The Standard Railroad of America.” They complained of rude service in the stations and trains and poor food on the dining cars. General Atterbury, the last of the Cassatt men to rule the PRR, would survive only five years longer than Rea. Exhausted by the ardors of running his beloved road during the darkest days of the Great Depression, the general would step down in 1935, not yet seventy, and die soon thereafter.

For decades Americans had resented the power and arrogance of the railroads. Now, disgruntled passengers had a liberating alternative: the automobile. It is impossible to overstate the bracing, heady freedom, the delicious convenience of the motorcar. You came and went on your own schedule, self-sufficient, setting the heat and air to your own liking, stopping as you pleased, sharing your car with no annoying strangers who talked too much. Back in 1910 few imagined—certainly not the railroad kings like Cassatt or Rea—that balky expensive motorcars, largely the gleaming playthings of the rich, might ever become a reliable (much less competing) form of long-distance transportation. But then came Henry Ford and the Model T. It was true that as yet the nation had no real highway system. It was an ominous sign of the times for the PRR that the next (and longest) subaqueous Hudson River tunnel, the state-financed Holland Tunnel, dedicated on November 13, 1927, served only cars and trucks driving between New York and New Jersey.

If it had been hard to imagine the car as a competitor to the railroad, airplanes seemed an even more far-fetched rival. It was only after World War II that the true dimensions of the combined threat hit home. In 1958, the Pennsy and other railroads, which had long run their sprawling rail empires with private capital, spent $1 billion of their own funds for maintenance of their facilities and paid $180 million in taxes. That same year, the U.S. government spent six times that sum—$10.3 billion—building highways for automobiles, trucks, and buses, thus helping to siphon off rail customers. While the federal government built the forty-thousand-mile interstate highway system as part of national defense, the Wall Street Journal pointed out trucks were hauling more and more freight “with the roadbeds being supplied at public expense.” Government then spent yet another $431 million that year on the nascent airlines and airport construction. The PRR, which carried far more passengers than any other road, was competing on very unequal terms with its new taxpayer subsidized rivals. Moreover, the glamour and excitement once attached to private cars and luxurious trains hurtling to distant big cities or resorts, chic couples enjoying sunsets through the dining car windows, was shifting inexorably to cars and airplanes.

Back in 1939, railroads carried 65 percent of intercity passenger traffic. In 1945, when MGM set key scenes of the Judy Garland love story The Clock in the General Waiting Room, Penn Station handled 109 million passengers, an all-time peak. But when World War II ended, so did those huge crowds. By now the Lincoln Tunnel was also open, giving yet more motorists and buses easy entry to midtown Manhattan. PRR officials watched with alarm as their share of Penn Station passengers plummeted from wartime highs of forty-four million riders each year to a quarter of that. By 1960, railroads carried only 29 percent of intercity passenger traffic. A quarter of travelers were boarding sleek airplanes and soaring through the clouds to their destinations. The PRR saw their losses balloon to $70 million a year as they indignantly protested (to no avail) the double standard that had their postwar rivals operating out of brand-new government-built bus stations and airports, while the PRR struggled to pay New York City $1.3 million in taxes for Penn Station. It was absurdly unfair.

As for Penn Station, even back in 1937 the PRR knew it needed freshening up and refurbishing. At almost thirty years old its beautiful pink granite facades had grown dirty, its golden Travertine marble interiors dingy, and its walls cluttered with advertising and ill-conceived signs. Designer Raymond Loewy, who had so brilliantly redesigned the look of the PRR’s locomotives, proposed cleaning and painting the arcade, cleaning the General Waiting Room and lighting Guerin’s map murals, almost invisible under accumulated grime, then creating new drama by floodlighting both the arcade and the General Waiting Room. He thought the concourse skylight ribbings should be painted light gray rather than black. But in that Depression year, nothing came of his suggestion.

Twenty years later, the station was filthier than ever and its grandeur badly faded. New Yorkers and modern architecture critics became scornful of the sadly neglected train station as outmoded. A half-hearted cleaning of the bottom ten feet led one New Yorker to liken the PRR officers and their station to “a small child who would wash his hands but never his wrists; either there should have been no cleaning at all, or the whole building should have been given a gentle washing.” Author Lorraine B. Diehl in The Late, Great Pennsylvania Station, describes how “the glass-domed roof in the concourse was darkened, grimy with soot. Broken windows were replaced with sheets of metal. ‘They didn’t take good care of it,’ said Archie Harris, a former baggageman for the old station…In the main waiting room the six lunette windows were clouded with dirt, and the Jules Guerin murals beneath them were little more than dark, colorless expanses.”

Now, the beleaguered PRR, which was openly talking about selling air space to build a skyscraper over the station to lessen its deficits, defaced McKim’s General Waiting Room with what came to be disdainfully called “the clamshell.” Designed by architect Lester C. Tichey and presumably intended to signal airportlike modernity, the monstrous crescent-shaped plastic clamshell served as the illuminated canopy roof of a highly visible new ticket counter, replete with television monitors and garish fluorescent light. Occupying the whole middle of the General Waiting Room and tethered with many wires to McKim’s monumental pillars, this modern excrescence mainly acted to “block access…to the concourse,” writes Diehl. Moreover, to make space for it, “both the ladies’ and the men’s waiting rooms were removed, and in a half-hearted gesture to the comfort of passengers who would no longer have anyplace to sit, the railroad installed a few benches in the concourse. To reach these, passengers were forced to take a labyrinthine path…It was during this time that automobile displays, fluorescent-lighted advertisements, and flashy glass-and-steel storefronts invaded the station.”

Critic Lewis Mumford could not believe his eyes when he saw the clamshell, which he denounced as “the great treason to McKim’s original design.” He wondered, “What on earth were the railroad men in charge really attempting to achieve? And why is the result such a disaster?” Mumford said one could only be grateful Cassatt was not still alive to see what his successors had wrought. “The only consolation,” he wrote innocently, “is that nothing more that can be done to the station will do any further harm to it.”

Desperate to raise money and indifferent to its own monumental gateway, the PRR promoted one plan after another to exploit the valuable air rights above Penn Station. In 1954, Lawrence Grant White, son of Stanford White and now head of McKim, Mead & White, heard that the PRR had secretly struck a deal and arranged to meet the developer. “I lunched yesterday with William Zeckendorf, who said that he was negotiating with the P.R.R. for the Pennsylvania Station in New York, with the avowed purpose of tearing it down and erecting a 30 story building upon the site. I had already told him at a previous dinner that I deplored tearing down such an important building, but was afraid neither I nor my firm could do anything to stop it; and that if it was to be torn down we should like, as architects for the P.R.R., to have some professional connection with the building that was to be erected…After an excellent lunch in his fabulous setting, he promised to keep us in mind.” That deal—Zeckendorf’s “Palace of Progress”—came to naught. Still, writers like Lewis Mumford clearly had no inkling even four years later, in 1958, that the PRR was actively seeking deals that required demolishing McKim’s station.

On July 21, 1961, the PRR finally announced with great fanfare that it had its deal, with developer Irving Felt. A new Madison Square Garden would arise above the station, a $75 million “entertainment center” featuring a thirty-four-story office tower, a twenty-five-thousand seat sports arena, a twenty-eight-story luxury hotel, parking garages, and bowling alleys. Nowhere did the article actually mention the necessary razing of Charles McKim’s great temple. (Oddly, newspapers had taken to identifying the station’s architect as the far more famous Stanford White.) By the time the PRR had its long-sought deal, Lawrence White had been dead five years, a devoted husband and father who had left behind a large brood of grown children. As for engineer Gustav Lindenthal, he had finally seen constructed what he had never ceased to promote—a bridge spanning the Hudson River. Alas, the handsome George Washington Bridge was not his design, and served only motorized vehicles. The dashing and cosmopolitan George Gibbs had been the final member of the board of engineers to go, dying in 1940.

Only Evelyn Nesbit survived from Gilded Age Gotham, her ethereal girlish beauty long gone. After the Thaws had abandoned her, she had triumphed in a series of smash hit vaudeville shows, but these interludes of showbiz success merely masked her private struggles with alcoholism, morphine addiction, suicide attempts, and the necessity of earning a living. Over the years she sold her story again and again to various newspapers and publishers. In 1955, the movie The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing made Evelyn, now age seventy and given to wearing heavy spectacles, briefly known to a new generation. “You must be wiser than most women and wealthier than most women if you are beautiful,” Evelyn told an interviewer then. “For there is no way to avoid danger if you are beautiful.” She had raised a son she said was fathered by Thaw (he denied it), and in her old age was living modestly in Los Angeles and teaching ceramics. She had long outlived Harry Thaw, dead in 1947 of a heart attack. Mad Harry had gained his freedom, only to revert with a vengeance to his wastrel ways, a regular item in the yellow press with his brawls, sordid flings, costly cover-ups, and bailouts.

Through the ballyhoo of the new Madison Square Garden deal, a handful of Manhattan architects discerned that the Pennsylvania Railroad Company intended to demolish its classical New York station. In spring 1962, this small group raised the alarm, banding together as the Action Group for Better Architecture in New York. On August 2, 1962, they marshaled two hundred concerned architects and others, elegant in their suits, the women in pearls and high heels, and set up a picket line outside the station at five o’clock as the sea of humanity flowed in and out for the evening rush hour. The architects, many of them renowned modernists, marched carrying picket signs emblazoned with slogans: “Don’t demolish it! Polish it!” and “Save Our Heritage” or “Action Not Apathy!” They buttonholed commuters and gathered several hundred signatures on petitions to stop the demolition.

Later that evening, several journeyed out to the Port Authority’s Idlewild International Airport to greet Mayor Wagner as he jetted back from a European vacation, pleading with him to join their crusade. Eventually, prodded by James Felt, chairman of the City Planning Commission and, oddly, brother of the very developer planning to destroy Penn Station, the mayor appointed a Landmarks Preservation Commission. But it had no real power yet. And there were rebuffed suggestions that the Port Authority take over Penn Station, as it had McAdoo’s New Jersey trains, which became known as the PATH, or the Port Authority Trans-Hudson.

The AGBANY architects were stunned at how few of their fellow citizens seemed to care. “People never heard of landmarks in 1962,” said Norval White, chairman of the group. “They didn’t realize what they were about to lose.” Norman Jaffe, another member, recalls his boss, architect Philip Johnson, warning, “You can picket all you want, but it’s not going to do any good. If you want to save Pennsylvania Station, you have to buy it.” “There was not consciousness among most New Yorkers of the value of old architecture,” said Elliot Willensky. “People wanted automobiles, suburban houses,” explained Kent Bartwick, a future chairman of the city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission. “There wasn’t much affection for the city itself around the country.”

Perhaps the hard truth was this: New Yorkers had never come to really love Penn Station. Charles Follen McKim, an architect rankled by the very skyscrapers, crowds, and cacophony that embodied modern New York, had designed a classical monument out of step with its own time and place. In 1939, Fortune magazine had ungraciously described McKim’s masterpiece as “a landmark from Philadelphia [that] squats on the busiest part of underground New York.” The Fortune article about the station, while affectionate about men like “Big Bill” Egan and station cats (two mousers), was otherwise grudging: “Pennsylvania Station affronts the very architectural rationale on which New York is founded by daring to be horizontal rather than a vertical giant. Many New Yorkers unconsciously resent the Pennsylvania Station for that reason…To sensitive New Yorkers the station’s body is on Seventh Avenue, but its soul is in Philadelphia…The New York Central Railroad, on the other hand, was put together in New York and New Yorkers think of the Grand Central Terminal as a native…it has the grace to be newer, more vertical, and compactly efficient in a way New Yorkers admire.” In short, the Pennsylvania Station was the work of men who did not love New York. It seemed that the subsequent decades—as even Penn Station’s grandeur had faded with grime and neglect—had done little to overcome that lingering native resentment. And so, the plans advanced for the destruction of one of the city’s noblest civic spaces and monuments.

Aside from the AGBANY architects, a few lone voices expressed outrage. The New York Times and its architecture writer, Ada Louise Huxtable, inveighed against “carte blanche for demolition of landmarks…We can never again afford a nine-acre structure of superbly detailed solid travertine…The tragedy is that our own times not only could not produce such a building, but cannot even maintain it.” The president of the PRR, A. J. Greenough, defended the impending destruction, saying in a letter to the Times that “Pennsylvania Station is no longer the grand portal to New York that it was in the days of the long-line passenger travel.” One city official said in an interview, “Pennsylvania Station is one of the city’s great buildings of our time. I’m working on a plan to save the columns.” Even that rather pathetic gesture was beyond the city’s ken.

On October 28, 1963, as the very skies seemed to weep a gentle rain, desecration and demolition began. By eleven o’clock, the first of sculptor Weinman’s twenty-two imperial Roman eagles, symbol of the Caesars, had been detached from its aerie and lowered to the pavement. There that imposing stone raptor looked trapped, the three-ton centerpiece of a group photo of grinning officials wearing hard hats. The station’s main clock was sentimentally set at 10:53 to signal the opening date of the station, 1910, and its lifetime, fifty-three years. That afternoon the AGBANY architects reappeared to march silently in protest, wearing black armbands and hoisting picket signs reading simply, “SHAME!” as the wrecking team attacked with jackhammers.

“Until the first blow fell no one was convinced that Penn Station really would be demolished,” editorialized the New York Times, “or that New York would permit this monumental act of vandalism against one of the largest and finest landmarks of its age of Roman elegance…Any city gets what it admires, will pay for, and ultimately, deserves. Even when we had Penn Station, we couldn’t afford to keep it clean. We want and deserve tin-can architecture in a tin-horn culture. And we will probably be judged not by the monuments we build but by those we have destroyed.”

By the summer, the wrecking crews, working carefully in the sticky New York heat not to disrupt the regular comings and goings of the six hundred trains in the station below them—the part built by George Gibbs—were desecrating McKim’s General Waiting Room, with its great lunette windows streaming in huge shafts of light. “A half century of emotion hung in the air,” writes Lorraine B. Diehl, “textured with memories of two world wars, a worldwide depression, and the private histories of people coming and going, meeting and parting. So many Americans passed through this room, leaving so much of themselves behind, that it seemed to belong to all of them.”

Now, as the wreckers pressed on, it “looked like the bombed-out shell of a great cathedral. Coils and wires hung like entrails from its cracked and open walls. The men with jack-hammers filled the air with noise and dust. The noise violated memory; the dust smelled of death.”

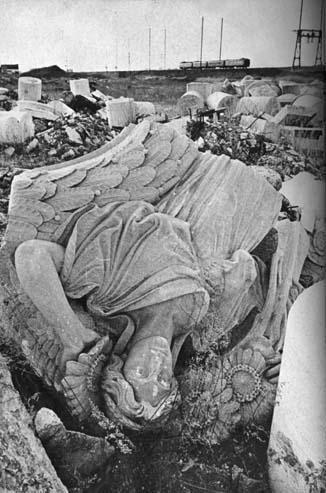

And so, slowly, McKim’s great temple built for the centuries was methodically dismantled over four years. By July 1966 the demolition crews were ready to remove Weinman’s quartet of female statues, each pair representing Day and Night and arrayed around one of the enormous outdoor clocks. Some were saved, but like much of Penn Station, the rest were unceremoniously dumped in the swamps of the Meadowlands, along with the gigantic Doric columns that had once lined Seventh Avenue. This strange instant ruin, complete with snapped and strewn columns and tumbled statuary, was all sadly visible to the passing Pennsylvania trains. By the time winter arrived in 1966, the destruction was complete. McKim and Cassatt’s monumental gateway was gone. Several weeks later, on January 18, 1967, Evelyn Nesbit died in a nursing home in Santa Monica. Just before Thanksgiving, the last of the Hudson River ferryboats made its final crossing, the Erie-Lackawanna’s service between Hoboken and lower Manhattan, departing for its terminal voyage at 5:45 p.m. from Barclay Street. Most of the three thousand passengers who “still rode the comfortable, broad-beamed boats chose to do so not so much for convenience as for romance.” Perhaps they would now drive their cars. It was the end of an era.

The statue of Cassatt, that visionary corporate leader, had been plucked from its niche and consigned to his alma mater, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, in Troy, New York, where it passed many years in storage before finding a home in the Pennsylvania Railroad Museum in Strasburg, Pennsylvania, along with his Sargent oil portrait. Samuel Rea’s statue was relocated to the outside Seventh Avenue entrance at 2 Penn Plaza, along with two of Weinman’s stone eagles. There Rea still stands, a monumental bronze sentinel looking much diminished and out of place, eternally watching the automobile traffic roar downtown, a poignant, little-noticed reminder of splendor lost. As for the new Penn Station, it was and is a mingy low-ceilinged affair little better than a bus depot. But neither the PRR’s desperate despoilment of its magnificent temple nor its doomed 1968 merger with its old rival the New York Central could save those proud old empires of passenger rail. Grudging government ownership was their unfortunate fate. And yet, when developers came to destroy Grand Central Terminal, outraged New Yorkers rallied to its defense, invoking a now powerful landmarks law.

All these decades later—as our love affair with cars and airplanes has soured—there is hope that New York can once again reclaim the grandeur of arriving by train in Gotham. Little could Alexander Cassatt have dreamed that the land his corporation sold on Eighth Avenue for a central post office would become so important. But it is this austere Corinthian General Post Office Building (a New York landmark long known as the James A. Farley Building) that opened in 1913 and its large 1934 addition that offer salvation. These elegant structures are now the centerpiece of a plan that envisions them reconfigured to serve the riders of New Jersey commuter trains. There is also serious talk of demolishing hideous Madison Square Garden and once again erecting a new train station worthy of New York.

Gotham’s Pennsylvania Station. “Through it one entered the city like a god,” wrote architect Vincent Scully of that old wondrous monument in his American Architecture and Urbanism. “Perhaps it was really too much,” Scully pondered, lamenting that “One scuttles in now like a rat.” Maybe now we can hope for a return to the grandeur of the past.

The statue of Day in the Meadowlands.