The Caraka-Saṃhitā, the oldest of the major āyurvedic texts,1 mentions three kinds of therapy (cikitsā): daivavyapāśraya (spiritual), yuktivyapāśraya (rational), and sattvāvajaya (psychological).2 Regardless of readily available (and well-known) definitions of these terms in canonical āyurvedic texts, practicing physicians most often quote the following Sanskrit verse as a prelude to any discussion of the treatment of mental illness, including those diagnosed as caused or exacerbated by spirit possession:

janmāntarakṛtam pāpaṃ vyādhirūpeṇa jāyate |

tacchāntair aushadhaiḥ dānaiḥ japahomārcanādibhiḥ ||

When it takes the form of disease, a moral transgression effected in another birth may be overcome through rituals of pacification [śānta], medicines [auṣadha], gift giving [dāna], repetition of the name of god [japa], fire offerings [homa], temple offerings [arcana], etc.3

This verse is used conventionally to explain daivavyapāśrayacikitsā (treatment based on daiva or fate, “spiritual” treatment employed to alleviate the effects of karma or actions performed in past births).4 Although a detailed discussion of the specifics of daivavyapāśraya- (and yuktivyapāśraya-) cikitsā is given later in this chapter,5 the verse, for us too, is a window into the general subject of mental illness, specifically disease-producing spirit possession.

This chapter is organized around the general theme of bhūtavidyā, the vidyā (science) of bhūtas (existent beings),6 most of which are invisible or assumed to be inhabiting other beings, the most important of which is humans, and are believed to cause various diseases, including certain forms of mental illness. This is a vast subject in India, but the present discussion examines only a few of the many texts within a surprising number of genres in which this is delineated. These include the Atharvaveda (AV) and its ancillary texts, the first millennium C.E. canonical āyurvedic texs, certain Tantras and dharmaśāstra texts, and texts otherwise regarded as philosophical. In Chapter 6, we examined a bhūtavidyā section from the Mahābhārata (MBh, 3.216–219). This is augmented in the present material. After discussions and translations of the key passages in the early āyurvedic texts and a complementary passage in the Sāṃkhyakārikā, we discuss certain modern interpretations of the āyurvedic passages, employing an important early Tibetan medical text as a counterpoint. Then we expand the discussion to include material on bhūtavidyā from the tantric and dharmasastra texts, as well as from a few contemporary ethnographies. The primary purpose of this examination, as of much of the remaining parts of the chapter, is to illustrate that India has a long history of viewing disease-producing spirit possession in moral terms: that behavior, viewed within a framework of moral concern, is a major component in the diagnosis of mental illness, more specifically in the diagnosis of spirit possession.7 Along the way it is necessary to discuss at length terms used for certain important possessors, in particular the graha and the piśāca. The chapter closes with discussions of diagnosis and treatment, drawn from both classical āyurvedic texts and contemporary practice, which do not always coincide. It would be a mistake to assume that the āyurvedic texts and traditions are invariable, unchanging, in agreement, or applied consistently in practice. Indeed, in response to changing cultural and intellectual practices, these traditions increasingly embraced elements of Tantra, dharmasāstra, and unclassified local practices, producing a mosaic around bhūtavidyā that, like so much of Indian praxis, leaves everything different, yet somehow the same.

Because possession was widely regarded as an affliction, whether for good or ill, it was medicalized very early. Āyurvedic texts of all periods locate possession within a category of pathology called unmāda (madness), though it is commonly known in āyurvedic circles more sanguinely as mānasika-roga (mental illness). Within that category, possession is regarded as an affliction that enters a person from outside, a condition with “exogenous” (āgantuka) causes,8 beyond the scope of identifiable medical or social pathology. In this way, it was regarded as suffering of divine origin (adhidaivika duḥkha), “effected by providential causes or acts of the gods, that is, factors that are beyond human control.”9 This view is expressed consistently from the early compendia of Caraka, Susruta, and Vāgbhaṭa, through the later commentaries and independent āyurvedic treatises of the mid- to late second millennium.

Complementary to this viewpoint, a theoretical system of bhūtavidyā developed. This was not a static concept, and, as we shall see, it went through significant changes over time, eventually becoming, more plainly, a demonology in which increasingly feral or bluntly amoral nonhuman beings were identified and classified. This helped foster an environment of spirit healing that was characterized by a great variation in pharmacological, ritual, and social modalities, many of which we discuss here.

The history of bhūtavidyā can be extended back to the early vedic period, in which, in the Ṛgveda (ṚV), the gods (deva, sura) were distinguished from their archenemies (asura, dānava), and in which the battle between the gods and demons was eternally fought, often to a standstill, though with a slight, if temporary, advantage to the gods. The ṚV identifies other categories of ethereal beings as well, who opposed humanity rather than the gods. In form they were anthropomorphic but, like the gods, insubstantial or, more accurately, endowed with a different substantiality. Among the most important of these beings were the gandharva, rakṣas, yātu or yātudhāna, and, later, the piśāca.10

The term bhūtavidyā first appears in Chāndogya Upaniṣad (ChU) 7.1.2, a text of the seventh century B.C.E. or perhaps a century or two later, where it is listed along with other vidyās including the Vedas, Purāṇas, divine knowledge (devavidyā), and understanding of brahman (brahmavidya).11 It is probable that at this date the term bhūta indicated any type of being, animate or otherwise, visible or otherwise, as certain texts describing domestic ritual (Gṛhyasūtras) prescribe offerings of water to be made to all beings, including deities, heaven and earth, days and nights, the year and its divisions, lunar asterisms, the spatial midregion, the syllable om, numbers, oceans, rivers, mountains, trees, serpents, and birds. In addition, the following celestial, semi-celestial, and other bhūtas are to receive similar offerings: apsaras, gandharva, nāga, siddha, sādhya, vipra (viz. brahmans), yakṣa, and rakṣas, as well as cows, ancestors, and teachers, both living and long deceased.12 Thus, by the mid-first millennium B.C.E. the word bhūta was applied to all manner of perceived ontological entities, including “spirits.” Bhūta may also have signified beings allied with an “element” (also indicated by the word bhūta), hence used to “personify the elemental fragments of creation, infinite in number.”13

One hymn of the ṚV (10.162) makes it clear that both the female body and fetuses were considered to be at great risk of possession by an exotic being, a rákṣas further identified as an ámīva, a flesh eater (kravy dam, 10.162.2) that separates the thighs and enters the womb while the husband and wife are sleeping together, in order to lick the inside of the womb (10.162.4) and, presumably, destroy the fetus.14 This was likely a precedent to the florid demonology in the MBh section on skandagarahas (child-snatchers) examined earlier, and similar pediatric sections of āyurvedic texts we examine more closely here. The ṚV, AV, and Yajurveda (YV) saṃhitās speak not only of spirits but of diseases, demons, and the punishments of Varuṇa and other deities pervading or overpowering the individual. As several scholars have pointed out, deities and spirits do not necessarily work against each other, nor do gods uniformly represent order while spirits represent resistance. As Shail Mayaram notes, spirit possession can “reproduce hegemony and hierarchy, [while] gods and goddesses, on the other hand, can sometimes be countercultural.”15 This is certainly the case in ancient and classical India, where reversals are as much the rule as the exception16 and is nowhere more transparent than in the āyurvedic texts, in which deity possession is medicalized in the same way as spirit possession.

dam, 10.162.2) that separates the thighs and enters the womb while the husband and wife are sleeping together, in order to lick the inside of the womb (10.162.4) and, presumably, destroy the fetus.14 This was likely a precedent to the florid demonology in the MBh section on skandagarahas (child-snatchers) examined earlier, and similar pediatric sections of āyurvedic texts we examine more closely here. The ṚV, AV, and Yajurveda (YV) saṃhitās speak not only of spirits but of diseases, demons, and the punishments of Varuṇa and other deities pervading or overpowering the individual. As several scholars have pointed out, deities and spirits do not necessarily work against each other, nor do gods uniformly represent order while spirits represent resistance. As Shail Mayaram notes, spirit possession can “reproduce hegemony and hierarchy, [while] gods and goddesses, on the other hand, can sometimes be countercultural.”15 This is certainly the case in ancient and classical India, where reversals are as much the rule as the exception16 and is nowhere more transparent than in the āyurvedic texts, in which deity possession is medicalized in the same way as spirit possession.

The ṚV (10.161.1) speaks of a gr hī: a female spirit that seizes people, causing death, disease, and fainting.

hī: a female spirit that seizes people, causing death, disease, and fainting.

muñc mi tvā havíṣā j

mi tvā havíṣā j vanāya kám ajñātayakṣm

vanāya kám ajñātayakṣm d utá rājayakṣm

d utá rājayakṣm t |

t |

gr hir jagr

hir jagr ha yádi vaitád enaṃ tásyā indrāgnī prá mumuktam enam ||

ha yádi vaitád enaṃ tásyā indrāgnī prá mumuktam enam ||

With this oblation I free you from unknown yákṣma [consumption] and royal yákṣma. Or if the grasper [gr hī] has seized [jagr

hī] has seized [jagr ha] him, free him from her, O Indra and Agni.17

ha] him, free him from her, O Indra and Agni.17

This feminine grasper is further mentioned in the Saunaka recension of the AV (AVŚ 16.5.1), where Sleep (svápna) is identified as her son. This is reminiscent of later analyses of possession, for example in tantric texts, where sleep and other forms of extinguished memory or obliterated personality, such as fainting, are described as symptoms of possession. Finally, one passage from the vedic Śrautasūtras recommends that if a person who is possessed (“touched”) by a spirit (bhūtopaspṛṣṭa) speaks during the performance of the pravargya, an important rite preceding the main ritual of the soma sacrifice,18 the adhvaryu or chief officiant should offer a stick lit at both ends into the āhavanīya (eastern fire), reciting mantras first to Agni (Taittirīya Āraṇyaka [TĀ] 4.28), then directing the words of the piśāca-possessed person to follow (and) possess (anvāvisya) the enemies of the sacrificer, urging death upon them (TĀ 4.21).19

The AV, as must be expected of a vedic saṃhitā, does not systematically discuss either bhūtavidyā or possession. Nevertheless, bhūtavidyā became more prominent in the medical sections of the AV, while the text mentions possession and remedial measures only casually. In spite of this, the allied sciences of Āyurveda, developed much later, always regarded the AV as their source text, as the inaugural text on Āyurveda.20 In several instances (AVŚ 1.16, 2.4, 3.9), the text provides mantras designed to empower amulets that are to be used to overcome víṣkandhas (disorders or disturbances caused by invasive and malevolent rákṣases [demonic beings in general] or piśācás [flesh-eating demons]).21 Other hymns (e.g. AVŚ 4.20, 5.29) reveal an awareness of malevolent ethereal beings, including piśācás and yātudh nas (wandering ethereal sorcerers). Another hymn (AVŚ 4.37) discusses gandharvás and their apsarás wives, beings with malevolent intent, though seemingly not equal in negative force to the rákṣas or piśācá.22 The AVŚ (2.25) identifies an embryo-eating (garbhādám) being called a káṇva, extending the notion from the ṚV that pregnancy had to be protected with great care.23 The most common word for such invasive disease-causing spirits in Āyurveda is gr

nas (wandering ethereal sorcerers). Another hymn (AVŚ 4.37) discusses gandharvás and their apsarás wives, beings with malevolent intent, though seemingly not equal in negative force to the rákṣas or piśācá.22 The AVŚ (2.25) identifies an embryo-eating (garbhādám) being called a káṇva, extending the notion from the ṚV that pregnancy had to be protected with great care.23 The most common word for such invasive disease-causing spirits in Āyurveda is gr hī, a term inherited from the ṚV and AV. An example of a ritual invocation for the removal of such spirits occurs in AVŚ 6.112.1: “O Agni, foreknowing, loosen the fetters of the gr

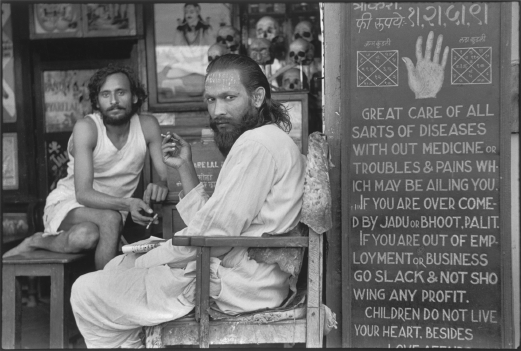

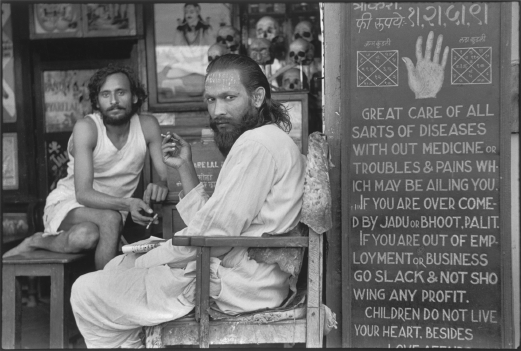

hī, a term inherited from the ṚV and AV. An example of a ritual invocation for the removal of such spirits occurs in AVŚ 6.112.1: “O Agni, foreknowing, loosen the fetters of the gr hi.”24 Thus, upon diagnosis of disease-causing possession, ritual was a prescribed therapeutic adjunct to medical procedures like herbal treatments or surgery.25 This multifaceted approach to healing has continued undiminished in India. For example, the Tantrarāja Tantra (31.27–29, 67) prescribes that a mannequin (puttalī) of clay mixed with earth from a cremation ground, ashes, salt, ginger, garlic, asafoetida, and so on, representing an enemy, be stabbed with a thorn or nail if, due to injury, one is possessed by a piśāca (piśācāviṣṭa), thus dispatching the enemy to Yama’s world.26 This kind of “folk medicine” may be found today in India, as K. P. Shukla discovered while conducting his study of traditional healers near Varanasi in 1969–71.27 Later we turn to further examples of this from the Īśāṉaśivagurudevapaddhati and some derivative Keralan traditions.

hi.”24 Thus, upon diagnosis of disease-causing possession, ritual was a prescribed therapeutic adjunct to medical procedures like herbal treatments or surgery.25 This multifaceted approach to healing has continued undiminished in India. For example, the Tantrarāja Tantra (31.27–29, 67) prescribes that a mannequin (puttalī) of clay mixed with earth from a cremation ground, ashes, salt, ginger, garlic, asafoetida, and so on, representing an enemy, be stabbed with a thorn or nail if, due to injury, one is possessed by a piśāca (piśācāviṣṭa), thus dispatching the enemy to Yama’s world.26 This kind of “folk medicine” may be found today in India, as K. P. Shukla discovered while conducting his study of traditional healers near Varanasi in 1969–71.27 Later we turn to further examples of this from the Īśāṉaśivagurudevapaddhati and some derivative Keralan traditions.

AVŚ (6.111) is a hymn to be recited as a palliative for únmāda. Kenneth Zysk sees:

two types of insanity or madness mentioned in the charm: únmadita which implies the demented state brought on by the patient himself as a result of his infringement of certain divine mores or taboos; and únmatta which suggests an abnormal mental state caused by possession by demons, such as rakṣas-s (verse 3). To the ancient Indian, insanity, like death, was considered to be a state when the mind leaves the body (verse 2). Likewise the patient exhibited the distinctive symptom of uttering nonsense (verse 1).

In order to cure such a condition, the healer had to return the mind to the body (verse 4). He did this primarily by making offerings to the gods in order to appease them, in the case of únmadita-madness (verse 1). He also prepared medicines, perhaps to calm the patient, to drive away the evil forces invading his body, in the case of únmatta-madness (verses 2, 3). There is also the suggestion that a victim was restrained, perhaps in a sort of straitjacket, presumably so that he could not harm anyone (verse 1).28

The hymn reads as follows:

1. O Agni, for me, release this man who, bound [and] well-restrained, utters nonsense [l lapīti]. Hence, he shall be making an offering to you when he becomes sane [ánunmaditaḥ].

lapīti]. Hence, he shall be making an offering to you when he becomes sane [ánunmaditaḥ].

2. If your mind is agitated, let Agni quieten [it] down for you. [For] I, being skilled prepare the medicine, so that you may become sane.

3. I, being skilled, prepare the medicine so that he, insane [únmaditam] because of a curse of the gods and demented [únmattam] because of the rákṣas-demons, may become sane.

4. Let the Apsarases return you; let Indra [and] Bhaga [return you; in fact,] let all the gods return you so that you may become sane.29

In examining this passage, it is important to note that if Zysk’s interpretation is correct, the division it describes foreshadows the later āyurvedic distinction between unmāda caused by accountable pathological factors and unmāda brought on by unaccountable invasive entities. Although I do not see in verse 2 evidence for the assertion that “insanity, like death, was considered to be a state when the mind leaves the body,” nevertheless the deployment of únmaditam and únmattam in verse 3 is striking, and the use of the stronger, more direct, únmattam for madness caused by possession is more notable still.30 However, in the absence of evidence for systematic usage of these words in the AV it is questionable whether this is more than a fortuitous effect of the poetic form. In any event, it does appear that at this early stage a distinction was seen between pathological madness and madness caused by possession.

It is useful to consider the deployment of gods (and, we can easily speculate, demons) as arbiters of moral action in the AV, and compare this to the much later Tantras, which also describe the openness of individuals whose moral transgressions made them vulnerable to possession by disease-causing spirits, a topic we discuss at length below. Sanderson observes that, according to the Netra Tantra and Jayaratha’s Viveka on Abhinavagupta’s Tantrāloka, “Yoginīs, Śākinīs and other female obsessors suck life from their victims into themselves as an offering to their regent Mahābhairava enthroned in their hearts.”31 Sanderson demonstrates that, according to brahmanical thought, such possession was due to the relaxation of both self-control and conformity to one’s dharma. Thus, “these ever alert and terrible powers of the excluded could enter and possess, distorting his identity and devouring his vital impurities, his physical essences.… Possession, therefore, was doubly irrational: it obliterated the purity of self-control and contradicted the metaphysics of autonomy and responsibility.”32

In his Tantrāloka (15.595–99), Abhinavagupta cites the authority of the Kulagahvaratantra and Niśisaṃcāratantra as predecessors to his own symbolic interpretation of demonic possessors (graha). Sanderson states that these grahas “conceal the true self (autonomous, unitary consciousness) beneath a phantasmagoric pseudo-identity, contaminating and impoverishing it with categories unrelated to its essence.”33 These grahas are “obsession with caste (jātigraha), vedic learning (vidyā), the social standing of one’s family (kula), with orthodox conduct (ācāra), with one’s body (deha), one’s country (desa), and material prosperity (artha),”34 in other words, the demons of personal identity. We might compare this sense of possession as identification with aspects of the ordinary human condition to Kausikasutra 28.12, an early ritual commentary on the AV, in which “infringement of certain divine mores or taboos” is illustrated through the prescription of an Atharvavedic mantra (AVŚ 5.1.7) as an antidote for amatigṛhīta, possession by “cluelessness” (amati), another ordinary human condition. Dārila, the commentator on the KausSū explains this term as “one with no idea about dharma, artha, and kāma” (trivargaśūnyabuddhiḥ).35 This, however, does not go as far as Abhinavagupta in bringing symbolic weight to a possessing entity. Indeed, Abhinavagupta and his predecessors are the only figures in Sanskrit literature to provide an explicitly symbolic reading of possession, except, of course, if one considers the entities in the āyurvedic categories purely symbolic. Although the latter is doubtful, as we now investigate, the line between the symbolic and the ontologically actual in these texts is nearly erased.

The Āyurvedic Demonologies

Possession in the āyurvedic texts has been addressed before, notably by Mitchell Weiss,36 who analyzes Indian categories of unmāda and exogenous disease-causing spirits with reference to Freudian and other psychoanalytic categories.37 In addition, Jan Meulenbeld has succinctly described views and categories of bhūtavidyā set forth in different āyurvedic texts. These textual differences have been considerable and should be kept in mind in the ensuing discussions. Among the areas of disagreement were the nature of bhūtas, their ontological reality, their number and identity, their cultural origins, and what constitutes the discipline of bhūtavidyā, including knowing not just the names and descriptions of bhūtas but the diagnostics, pharmacology, and ritual treatment for possession by bhūtas.38

Weiss’s results, in my view, are not particularly helpful in understanding the āyurvedic categories and, like many comparative studies, make little attempt to bridge the cultural and philosophical gap between the loci of comparison, in this case India of two thousand years ago and Vienna of the early twentieth century. The psychoanalytic prism has the singular advantage of offering an explanation of possession as represented in these texts to a reader with interests in Freudian psychoanalysis, but it neither sheds much light on what these texts attempt to illustrate nor offers an effective model with which to evaluate notions of selfhood that arise from a consideration of possession as defined in these texts. In addition, by failing to consider the emic gravitas of possession, an interpretation that constantly looks over its shoulder at Freudian psychoanalysis unwittingly abets Western cultural and scientific hegemony and authority. As the foregoing discussion should make clear, the etiology and identification of bhūtas cannot be adequately examined in terms of any single theory.

Meulenbeld’s article is of quite a different nature. It provides insight into the complexity and contentiousness of first-millennium āyurvedic debate over the nature of unmāda, which are absent from Weiss’s study. It appears, in short, that the early compendia of Caraka and Susruta modernized the study of medicine in the first few centuries of the Common Era. One topic with which they were forced to grapple was the notion inherited from the AV and other earlier texts that nearly every disease could be personified or anthropomorphized and attributed to possession by spirits and other divine beings. In their attempt to make medicine more empirical, Caraka and Susruta placed distinct limits and conditions on this notion. They were not always in agreement, and this sense of debate persisted through the next millennium or so of āyurvedic textuality. Their fundamental solution to bhūtavidyā, however, was similar: They relegated it to a subcategory of unmāda and conditionally of apasmāra, both of which they believed to have a number of possible causes, including those that were inherent (nija) or explicable.

Caraka (Cikitsāsthāna [CaCi] 3) treats four categories of fever (jvara) brought about by external factors: (1) abhighātaja (those resulting from injury); (2) abhiṣaṅgaja (those resulting from afflictions by evil spirits, as well as emotional overload, including uncontrollable passion, grief, fear, and anger); (3) abhicāraja (those arising from sorcery, including hostile ritual, mantras and oblations); and (4) abhisāpaja (fever brought on by the curse of a spiritually advanced being). CaCi 3.123, addresses abhiṣaṅgaja fevers: “Abundant tears [are observed] in [fever caused by] grief; when fever is due to fear, terror becomes prominent; extreme agitation [is evident] when [fever] arises out of anger; nonhuman [symptoms are observed] in [fever arising from] possession by spirits [bhūtāveśe].”39

The foundational texts of Āyurveda, Caraka Saṃhitā (6.9.16ff.), Suśruta Saṃhitā (6.60), and Aṣṭāṅgahṛdaya Saṃhitā (ch. 6), discuss the “epidemiology of possession,”40 in this case bhūtatantra (doctrine of bhūtas), a category that includes bhūtonmāda (insanity produced by the influence of bhūtas).41 Although these enumerations are regarded as different categories of graha or bhūta, they share fundamental territory with categories of personality. This resonance is borne out in complementary sections of Caraka and Susruta, as well as in the most important texts belonging to the second chronological level of āyurvedic textuality, the Kāsyapa Saṃhitā and the texts of Vāgbhaṭa, which postdate the earlier compendia by four or five centuries.42

These sections describe sattvas—essences, personality types, or mental states43—as part of a discourse on embryology, the human body in its development from conception to birth. Many of these sattvas correspond in both personality and name to the various grahas listed in the bhūtavidyā sections.44 From this, we must assume that grahas or possessing entities may be viewed as substantialized or reified collocations of personality attributes. Nevertheless, it appears that the authors of these foundational texts maintained the distinction between native personality and grahas that independently personified these attributes. This is consistent throughout the canonical āyurvedic literature. Bhūtavidyā consists, formally at least, of two divisions (graha or bhūta), though in much of the literature they are used interchangeably, with the word graha attested more frequently. Nevertheless, when a distinction is required, the category of graha is used to denote bālagrahas, the mostly female possessors of pregnant women and children. But bhūtas are almost entirely male grahas that are known by their specified characteristics. Bhūtas may be regarded as subspecies under which no further taxonomic breakdown is required. Thus, the category bālagraha may include sixteen, eighteen, or more varieties, while grahas as subcategories of bhūta may be gandharvas, yakṣas, pitṛs, niṣādas, and so on, without further subspecies. The latter division consists of bhūtas called grahas, which the brahmanically constituted āyurvedic texts have drawn from vedic and other more “orthodox” sources.

This categorical and taxonomic arrangement is represented fairly consistently from the MBh through the āyurvedic literature and in modern folklore. These two divisions appear to emerge from quite distinct local traditions and probably from different strata of society as well. Their odd integration into the Vanaparvan of the MBh and the pediatrics sections of the āyurvedic texts suggests that bālagrahas existed outside the realm of Sanskritic culture and discourse until they were incorporated into the fold, Sanskritized, gaps filled in, and systematized, one for every year, and so on, as we saw in the MBh and see again later in this chapter. The more brahmanically inclined (if not always more benign or better-behaved) grahas were taken from an assortment of vedic texts, reconceptualized in a way that brought them into a closer, even familial, relationship, and presented in a coherent and systematic discourse. Another difference between them is that pregnant mothers and children possessed by bālagrahas appeared to maintain their “own” personalities, while those possessed by more orthodox bhūtagrahas appear to have been consistently overwhelmed by the personality of the possessing agent.

Subsequently, the project of bhūtavidyā, including taxonomies, diagnostics and treatment, provided the āyurvedic texts with an exegesis on, and to some extent a solution to, the problem of deviant personality management. Indeed, through the very organization of these passages, the texts have called into question the notion of personality. In a chapter titled unmādacikitsā (treatment for madness), Caraka (9.20–21) describes in detail the unmāda produced by possession (abhidharṣayanti; lit. “overpowering”) of eight kinds of divine and semidivine beings, as well as the characteristics of people who might be possessed by each one, a topic we address in detail shortly.45 It must be noted that all the canonical texts kept the bhūtavidyā sections distinct from the sections on bālagrahas. Although I am here including them both within the broader parameters of bhūtavidyā (knowledge of [nonhuman] entities), the texts regarded bālagrahas as a part of pediatric medicine, rather than of mental illness.

In a chapter of similar content, titled amānuṣopasargapratiṣedha (repulsion of contact by the nonhuman), Susruta (6.60.8–18) divides grahabalas into nine classes. First, however, he defines graha. “A graha,” he says, “is well-known as an unstable quarrelsome entity that engages in nonhuman activity and has knowledge of what is hidden or lies in the future. They afflict the unclean, [and] fracture [social] boundaries in whole or in part, even if the purpose of such affliction is [not explicitly malevolent, but] merely frivolous or to satisfy a religious obligation” (6.60.4–5). These are distinguished from bhūtas, a distinction that yields little practical difference, as Susruta himself observes (see Suśruta [Su] 6.60.27). Half a millennium later, in the Aṣṭāṇgahṛdaya Saṃhitā’s equivalent chapter, bhūtavijñānīyabhūtapratiṣedha (entities to be known and repulsed), this number grows to twenty (AH 6.4.9–44).46 This suggests that the canon of bhūtas, so to speak, was open, a fact verified by the introduction of grahas with non-Sanskritic names into the AH, a process that has continued to the present. This transition from folk to classical was discussed in Chapter 4, while commenting on descriptions of the phenomenology of possession as represented in modern ethnographies. Here, too, first-millennium chroniclers of mental illness not only did not standardize the list of grahas, which perhaps might be expected of a developing scientific enterprise, but encouraged an expansion of the list. The dynamics of this early interaction between folk and classical are clarified below, in the discussion of enumerations of grahas outside the primary āyurvedic literature.

Convulsions, or seizures of any kind, constitute another condition believed to be caused by malevolent spirits, as well as by planets, also called grahas, that are malevolent and badly placed in one’s horoscope. The general word in Sanskrit for “convulsion” is apasmāra (literally, “forgetfulness”), which is often wrongly assumed to signify epilepsy alone.47 The early medical texts did not consider that apasmāra could have an organic cause. This was only realized much later in Europe by Jean Martin Charcot (1825–1893), the “Napoleon of Neuroses,” an early founder of neurology and one of Freud’s teachers. Charcot developed the concept of hysteria and distinguished it from epilepsy, the former of which had psychological causes and the latter organic causes. One definition of apasmāra—striking because it is not in a medical text—is found in the Daśarūpa, a treatise on dramatic theory, which regards seizure as a transitory state (vyabhicāribhāva) of giddiness to be replicated in dramatic performance. The Dasarūpa states, “Apasmāra is āveśa induced, properly speaking, by the influence of the planets, by misfortune, etc. Its results are falling on the ground, trembling, heavy sweating, and slobbering, frothing at the mouth, etc.”48 Two synonyms of āvesa, given by Hemacandra, are apasmārarogaḥ (seizures as disease) and ahaṃkāraviśeṣaḥ (a variety of self-identity).49 We have confirmation of the latter in the sections from the Tantras cited by Sanderson above, which are roughly contemporaneous with Hemacandra, as well as from the much earlier KausSū. Apasmāra is also found as the name of a certain bhūta or disembodied spirit in South Indian mythology and appears most notably as the demon on whom Śiva Naṭarāja treads in the great temple in Chidambaram.50

The primary āyurvedic texts enter into significant detail on possessing entities. These passages shed light on the manner in which possession and possessing entities rearrange personality and behavior. They also reveal to some extent the constitution of selfhood as conceived by these texts. This makes it useful to translate several lengthy āyurvedic text passages in full.51 This is equally essential if we understand personality and behavior as paramount and grahas and bhūtas as materializations of these behaviors. Before translating these passages, however, we must first describe the nature of grahas.

Graha: Grasper and Possessor

As Susruta’s definitions of graha and bhūta clarify, the bhūtavidyā passages employ the word graha to describe certain kinds of bhūta. A bhūta, in its very etymology, is any existent ontological entity, while a graha is an entity further delineated by its ability to “grasp” or “hold” (√gṛh). The archetypal “grasper,” which the authors of these texts perhaps had in mind, is the alligator, which in Sanskrit is indeed called grāha. It is perhaps no accident, then, that a grāha is also an idea or notion, and a grāhaka is a perceiver, one who grasps an idea or notion. Consistent with the passage from ChU 7.1.2 cited earlier, if considerably pared down, later Sanskrit literature limits the term to include only these exotic beings and the planets.

In Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad (BĀU) 3.2, Jāratkārava Ārtabhāga asks Yājñavalkya how many graspers there are, and how many overgraspers (katigrahāḥ katy atigrahā iti). There are eight of each, replies Yājñavalkya, and they come in pairs, a grasper that is overcome by its paired overgrasper (atigrāheṇa gṛhītaḥ): the inbreath (prāṇa) which is overcome by the outbreath (apāna), speech (vag) by name (nāman),52 tongue (jihvā) by taste (rasa), eye (cakṣus) by form (rūpa), ear (srotram) by word (sabda), mind (manas) by desire (kāma), the two hands (hastau) by action (karman), and skin (tvac) by touch (sparsa). Taking this as a guide, a graha or personality-laden ethereal grasper would assume the role of the overgrasper during possession, taking control of the sense organs and sensory functions of the individual, who would in a healthy individual be the grasper of these organs and functions as well as their perceiver, a complex person consisting of both grāha and grāhaka.

One of the common meanings of the word graha in Sanskrit is “planet,” of which nine are counted, the seven after which the days of the week are named, plus the two nodes of the moon, Rāhu and Ketu, which are held to be responsible for eclipses.53 According to the astrological literature, planets are called grabas because they grip or hold people in their power. The Bṛhatparāśarahoraśāstra (3.4) says, in what is surely a very old idea, “those which grasp [gṛhṇanti], constantly moving in the sky, are called planets [grahāḥ].”54 Indeed, one of the late books of the AV, possibly dating to 1000 B.C.E., uses the word graha to refer to planets, at least as they are represented in the Indian system. The planet named here is Rāhu, not actually a planet but, rather, the northern node of the lunar path, which W. Caland identifies, at least in this hymn, with Vṛtra, the cosmic serpent, thus a “grasper” par excellence.55 An eclipse is also called grahaṇa (bhāskaragrahaṇam [solar eclipse]) in Varāhamihira’s Bṛhat Saṃhitā.56 The grahas Rāhu and (in later texts) Ketu, the southern node of the lunar path and thus not “planets” at all, seize the sun or moon, a celestial act of general affliction that requires ritual expiation.57 Whether human or cosmic, the result is the same: The sun and moon during an eclipse, as well as individuals who are “afflicted” by grahas, require remedial procedures often resembling those employed in cases of possession as described in medical texts. Thus the influence of planets resembles possession by bālagrahas in Āyurveda as well as in instances of pra√viś, discussed earlier. This influence from the planets is invasive, pervasive, and motivated from without.58 Consequently, the remedial or expiatory procedures recommended in astrological treatises are called grahaśānti (pacification of a planet).59

Two other related words that share many of the semantic attributes of possession are vigraha (an embodied image) and anugraha (grace). Both can attract the attention of a person and overwhelm one’s sense of identity. The primary meaning of vigraha, following its etymology, is “separation, isolation, conflict.” One of its most common occurrences is in Sanskrit grammar, where dissolution of compounds into their constituent parts is called (pada-)vigraha. Supporting this notion of division into individual units is its meaning in the srauta ritual, where vigraha refers to a “portion,” for example of soma or ghee, which has been removed or separated from the main vessel.60 Thus, in its early applications it conveyed a sense of individualizing, approximately the same sense it obtained in the MBh and the Purāṇas, where it indicated the form or image of a deity. In the only study of this word, G. B. Palsule states that vigraha “is something which is taken up or assumed. It is assumed by the jīva; it is something external, something shell-like, which the jīva assumes (vigṛhṇāti) temporarily. An ‘avatāra’ or incarnation is a vigraha, i.e. a form of the God which He has assumed.”61 After examining its occurrences in the epics and certain late Upaniṣads, Palsule concludes that vigraha appears in two contexts: “(1) assumption of a form, false impersonation or disguise; and (2) personification (real or imaginary).”62 Furthermore, because it connotes an assumed form, it never becomes a synonym of deha or śarīra, the usual words for “body.” Philip Lutgendorf records the contemporary North Indian notion among Vaiṣṇavas that “the Lord has four fundamental aspects [vigrah]; name, form, acts, and abode [nam, rūp, līlā, and dhām]—catch hold of any one of these and you’ll be saved!”63 This doubtless reflects a much earlier view, in which an embodied form (rūp) is a “portion” of a deity. This helps explain, linguistically at least, the Vaiṣṇava view that an image of Kṛṣṇa is not a “representation” of the Lord, but the Lord Himself (svarūpa).64 Thus, vigraha, like grāhi and graha, indicates an external presence appropriating or “seizing” form.

Anugraha (lit. “favor, kindness, assistance” in early literature) becomes a synonym of kṛpā (grace) in devotional literature.65 The Taittirīya Saṃhitā (1.7.2.3) says, in a passage that is fairly typical of anu√gṛh in early Indic usage, “[I have invoked] her [Iḍā] who favors with kindness [anugṛhṇ ti, i.e., extends her grace to] people in distress and nourishes [gṛhṇ

ti, i.e., extends her grace to] people in distress and nourishes [gṛhṇ ti, takes] them as they recover.”66 Anugraha does not appear in Upaniṣads until at least the mid- or even late first millennium C.E., in a few Saṃnyāsa Upaniṣads and sectarian Vaiṣṇava Upaniṣads, such as the Nārāyaṇapūrvatāpanīya and Gopicandana.67 A typical usage is found in the Kathāsaritsāgara, “realizing that the grace [anugraham] of Kumāra toward them had blossomed.”68 In all cases the meaning is mild compared to the “seizing” characteristic of other forms of √gṛh. The prefix anu- (following along) softens the sense of the verbal root, rendering the seizer’s engagement with the seized emphatically, if curiously, benevolent. Although anugraha never, to my knowledge, indicates destructiveness, disease, or sheer power, a further distinction is made in Śaiva Siddhānta: “God’s grace in its tender aspect is called anugraha and in its tough or punitive aspect, nigraha. It will be seen that even nigraha [restraint] is really anugraha because punishment is meted out only to correct and reform the erring individual.”69

ti, takes] them as they recover.”66 Anugraha does not appear in Upaniṣads until at least the mid- or even late first millennium C.E., in a few Saṃnyāsa Upaniṣads and sectarian Vaiṣṇava Upaniṣads, such as the Nārāyaṇapūrvatāpanīya and Gopicandana.67 A typical usage is found in the Kathāsaritsāgara, “realizing that the grace [anugraham] of Kumāra toward them had blossomed.”68 In all cases the meaning is mild compared to the “seizing” characteristic of other forms of √gṛh. The prefix anu- (following along) softens the sense of the verbal root, rendering the seizer’s engagement with the seized emphatically, if curiously, benevolent. Although anugraha never, to my knowledge, indicates destructiveness, disease, or sheer power, a further distinction is made in Śaiva Siddhānta: “God’s grace in its tender aspect is called anugraha and in its tough or punitive aspect, nigraha. It will be seen that even nigraha [restraint] is really anugraha because punishment is meted out only to correct and reform the erring individual.”69

Sāṃkhya Entities

The Sāṃkhya school of philosophy was rarely (if ever) followed in India as an independent soteriological path, as were most other schools. However, it had a major, even pervasive, influence on the “higher” schools of yoga and Vedānta, on the Mahābhārata, as well as on many other systems of thought, including Āyurveda. Without Sāṃkhya, Āyurveda would look very different; indeed, it is Sāṃkhya that weaves the disparate threads of Āyurveda into a coherent system. The evolutionary principles (tattva-) that constitute Sāṃkhya’s main doctrine are the building blocks of the āyurvedic body, mind, and cosmos.70 Within a set of fourteen types of sentient (bhautikasarga) that hierarchizes beings “from Brahmā down to a blade of grass,” the Sāṃkhyakārikā (SK, 53–54), which predates Caraka and Susruta, presents a list of divine beings that was almost entirely accepted by the latter two āyurvedic authorities. This is not to assert, however, that the SK was the sole influence on the early āyurvedic texts; such ethereal beings were, we might say, very much in the air at that time.

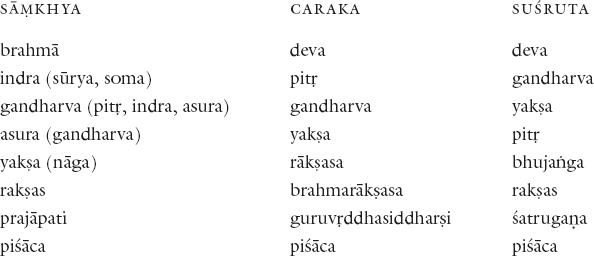

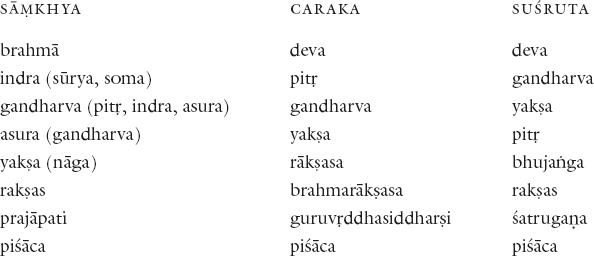

More specifically, SK 53–54 speaks of divine (daiva) realms, the human realm, and lower realms of animals, plants, and immovables, though it does not list these realms by name. This is left to the commentaries, particularly the Suvarṇasaptati (on kārikā 53), which lists the daiva realms as Brahmā, Prajāpati, Indra, Gandharva, Asura, Yakṣa, Rakṣas, and Piśāca. However, the Sāṃkhyasaptativṛtti on kārikā 53 lists Brahmā, Prajāpati, Indra, Pitṛ, Gandharva, Yakṣa, Rakṣas, and Pisāca; thus it eliminates Asura and places Pitṛ before Gandharva.71 The Sāṃkhykārikābhāṣya of Gauḍapāda on the same kārikā lists the divine realms as Brāhma, Prājāpatya, Saumya, Aindra, Gāndharva, Yākṣa, Rākṣasa, and Paiśāca. These are realms named after the specific divine or semidivine beings believed to characterize or inhabit them. In this list Soma, the lunar realm, is indexed before Indra’s realm, in place of either the Pitṛ or Asura realms. The anonymous commentary on the SK called Jayamaṇgalā presents the following list: Brahmā, Prajāpati, Sūrya, Asura, Gandharva, Yakṣa, Rakṣas, and Piśāca. In this list Sūrya replaces Indra, and Asura occurs once again.72 The Yuktidīpikā, an important early Sāṃkhya text, lists Nāga in the place of Yakṣa. These lokas (realms) assuredly represent domains in which beings that possess humans reside. These beings have cosmological roles and functions other than possessing innocent people; they comprise a balance of living beings that necessarily populate the existent worlds. Therefore, they may be regarded as archetypal ingredients in a cosmic soup that blends and separates in different consistencies according to proximity, locational strength or weakness, and so on, functioning much like elements of a multivalent, multidimensional, and complex personality. This is the Sāṃkhya cosmos and the Sāṃkhya individual, the thousand-headed, thousand-armed being, ever-shifting within itself. It is a classical expression of fluidity, which is so apparent in the modern ethnographies. The list of divine or semidivine beings in the SK may be briefly compared to similar lists in Caraka and Susruta.73

The Bhūtavidyā Sections of Caraka, Suśruta, and Aṣṭāṇgahṙdaya Saṃhitās

A good general statement introducing the textuality of bhūtavidyā is Caraka’s succinct description of unmāda:

The general symptoms of disease caused by unmāda are psychic confusion, agitated consciousness, unsteadiness of vision, impatience, unrestrained speech, and emptiness of heart. Such a person, whose mental processes are confused, does not experience pleasure or misery, cannot behave properly or understand dharma, finds no peace at all, and has dissipated memory, intellect, and power of recognition. In this way, then, his mind wavers. (6.9.6–7)

A few verses later, Caraka gives a more in-depth explanation.

Carakasaṃhitā 6.9.16–21:

16. Externally induced [āgantu] [madness, unmāda] has as its [direct] cause attacks [abhidharṣaṇāni] by gods [deva], seers [ṛṣi], celestial musicians [gandharva], flesh-eating demons [piśāca], semidivine protector demons [yakṣa], dangerous demons [rakṣas], and deceased ancestors [pitṛ]; [indirectly] it is the result of incorrectly performed internal and external vows, etc., and actions from a previous existence.74

17. If, as a result of one’s knowledge, skill, strength, and other qualities, one’s speech, heroism, power, and actions resemble those of an immortal, one should declare about him that his unmāda is brought about by a bhūta, so long as the time of the onset of this unmāda remains unspecific.75

18. By virtue of their own powers and attributes [guṇaprabhāvaiḥ], the gods and the rest enter [visanti] the body of a man quickly and imperceptibly, without defiling it, like a reflection in a mirror or sunshine in a crystal [sūryakānta].

19. The time of the attack by the gods, etc., as well as an account of previously observed symptoms were already stated in the nidāna section [CaSū 2.7.12]. Now understand the various forms of unmāda, as well as the times and the kinds of people upon whom these forms chance to fall.

20.1 Let it be known that one who has a soft gaze, is serious and modest, not given to anger, does not crave sleep or food, who has little perspiration, urine, feces, and flatulence, who has a sweet scent and a face like a lotus in bloom is afflicted with unmāda [caused by possession] by the gods.

20.2 Let it be known that one whose actions, diet [āhāra], and speech reflect a curse [abhisāpa], malevolent spell [abhicāra], or subtle intention [abhidhyāna] of a preceptor, elder, perfected being, or seer [guruvṛddhasiddharṣīṇām] is afflicted with unmāda [caused by possession] by any of them.

20.3 Let it be known that one whose gaze is unfavorable, is uncomprehending, languid, whose speech is blunted, lacks appetite, and is seized by indigestion is afflicted with unmāda [caused by possession] by deceased ancestors.76

20.4 Let it be known that one who is passionate, impulsive, sharp-tempered, serious, modest, enjoys wind instruments [mukhavādya], dance, song, food and drink, bathing, garlands, incense, and perfume, is fond of red garments, offering sacrifice [balikarma], and indulgence in humorous stories, and has a sweet scent is afflicted with unmāda [caused by possession] by a gandharva.77

20.5 Let it be known that one who sleeps, cries, and laughs frequently, is fond of dance, song, musical instruments, reciting sacred texts, telling stories, food and drink, bathing, garlands, incense, and perfume, has red and tearful eyes, vilifies the twice-born and physicians, and divulges secrets is afflicted with unmāda [caused by possession] by a yakṣa.

20.6 Let it be known that one whose sleep is disturbed, who dislikes food and drink, is very strong in spite of not eating, craves weapons, blood, meat, and red garlands, and is threatening is afflicted with unmāda [caused by possession] by a rākṣasa.

20.7 Let it be known that one who has a primary interest in laughter and dance, exhibits hatred and defiance of gods, brahmans, and physicians, [yet] recites hymns, the Vedas, mantras, and other canonical texts [śāstra], and self-flagellation with sticks, etc., is afflicted with unmāda [caused by possession] by a brahmarākṣasa.

20.8 Let it be known that one whose thoughts are unhealthy, has no place to stay, indulges in dance, song, and laughter, as well as idle chatter that is sometimes unrestrained, who enjoys climbing on assorted heaps of garbage and walking on rags, grass, stones, and sticks that might be on the road, whose voice is broken and harsh, who is naked and runs about, never standing in one place, who broadcasts his miseries to others, and suffers from memory loss is afflicted with unmāda [caused by possession] by a piśāca.

21.1 Under those circumstances, the devas attack [abhidharṣayanti] a person of pure behavior, skilled in religious austerities and scriptural study, generally on the first and thirteenth lunar days [tithi] of the waxing lunar fortnight [śuklapakṣa] after noticing a weakness [chidram].

21.2 The ṛṣis attack a person who is devoted to bathing, purity, and solitude, and well-versed in the teachings of sacred law and the Vedas [dharmaśāstraśrutivākyakuśalaṃ], generally on the sixth and ninth lunar days.78

21.3 The deceased ancestors [pitṛ] attack a person who is devoted to the service of his mother, father, teachers [guru], elders, spiritually perfected ones [siddha], and spiritual teachers [ācārya], generally on the tenth lunar day and on the day of the new moon.

21.4 The gandharvas attack a person of pure behavior who is fond of hymns of praise, singing, and musical instruments, who is fond of other men’s wives, perfumes, and garlands, generally on the twelfth and fourteenth lunar days.

21.5 The yakṣas attack a person who is endowed with intelligence, strength, beauty, pride, heroism, is fond of garlands, massage oils, and laughter, and is loquacious, generally on the seventh and eleventh lunar days of the waxing lunar fortnight.

21.6 The bramarākṣasas attack a person who dislikes scriptural study, religious austerities, internal vows, fasting, celibacy, and honoring deities, mendicants, and teachers, a brahman whose purity has been compromised or a non-brahman who speaks like a brahman, whose comportment is that of a hero, and who is fond of playing games in temple waters, generally on the fifth lunar day of the waxing lunar fortnight as well as on the day of the full moon.

21.7 The rakṣases and piśācas attack a person who is devoid of intelligence, who is a backbiter, lusts after women, and is deceitful, generally on the second, third, or eighth lunar days.

8.8 Thus, of the innumerable agents of possession [graha], the eight most prominent have been described here.

Suśrutasaṃhitā 6.60.1–28

1–2. Now we shall present the chapter on warding off the onset of non-human beings as it was accordingly explained by the illustrious Dhanvantari.

3. One who suffers an injury must always be protected from “wanderers of the night” [nisācara]. This topic was introduced before and will now be discussed at length.

4. A person in whom one finds knowledge of secrets or things that have not yet occurred, or is unstable or quarrelsome, and whose actions are not like those of a human may be regarded as possessed [saGrahaḥ].

5. They may harm one who is impure, uncontrolled [bhinnamaryādam],79 or injured; or if one is not injured they may harm for no other reason than the fun of harming or else because they are made welcome [satkāra].

6. The categories of “seizers” [graha] are innumerable, but the principal ones, which manifest in various forms, are divided into eight types.

7. These eight categories of deity [devagaṇaḥ] called “seizers” are gods [devāḥ], various categories of their enemies [śatrugaṇāḥ], celestial musicians [gandharva-], semidivine protector demons [yakṣāḥ], deceased ancestors [pitaraḥ], serpent spirits [bhujaṅgāḥ], ordinary demons [rākṣasāṃsi], and the class of flesh-eating demons [piśācajātiḥ].

8. A man who is contented and pure, has the proper scent and garlands, is strong and possessed of truthful and refined speech, is vibrant, steadfast, grants boons, and is devout is inhabited by gods [deva].

9. He who is sweaty, speaks badly of the twice-born, gurus, and gods; whose eyes are shifty, who is completely fearless and vigilantly seeks out evil ways; who is satisfied by neither food nor drink; and whose character is defiled is inhabited by enemies of the gods [devasatru].

10. One whose character is joyous, who frequents sandy river banks and the interiors of forests, who is well-behaved, who is fond of singing, perfumes and garlands, who laughs while dancing, is agreeable but is a person of few words is a man tormented by gandharva grahas.

11. One whose eyes are coppery, who is fond of wearing red clothes, is serious, quick-thinking, reserved, and patient, is vibrant and says, “What shall I give to whom?” is tormented by a yakṣa graha.

12. A person of peaceful nature whose clothes cover the left side, who supplies rice balls and water, properly arrayed, to the deceased, who desires and eats meat and sweets [pāyasa] made from sesame and jaggery [guḍa] is overwhelmed by pitṛ grahas.

13. One who sometimes crawls around on the ground like a serpent and licks the corners of his mouth80 with his tongue, who is drowsy and desires sweets made from jaggery, honey, and milk is known to be inhabited by a serpent spirit [bhujaṅgama].

14. One who desires meat, blood, and various kinds of alcoholic beverages, who is shameless, excessively harsh and powerful, is angry and immensely strong, who wanders about at night and detests ritual purity is seized by a rakṣas.

15. One whose hand is raised,81 is thin and severe, chatters endlessly, is foul-smelling, excessively impure, and staggers around, who eats a lot and enjoys isolated places, the cold, watery places and the night, and who is extremely uneasy and wanders around crying is inhabited by a piśāca.

16. One whose eyes are dull and gait is fast, who licks up saliva and other foamy substances from his own mouth, who is sleepy, falls and trembles a lot, and when falling due to injury from a mountain, an elephant or a tree, etc.,82 does not heal is afflicted by demons who intensify the condition.83

17–18. Deva grahas enter [visanti] on the full moon day, asuras at dawn and dusk, gandharvas generally on the eighth lunar day, yakṣas on the first lunar day, pitṛs and serpents [ uraga] on the fifth day of the waning lunar fortnight, rakṣases at night, and piśācas on the fourteenth lunar day.

19. As a reflection is to a mirror or other similar surface, as cold and heat are to living beings, as a sun’s ray is to one’s gemstone, and as the one sustaining the body is to the body, in the same way grahas enter an embodied one but are not seen.84

20. Severe austerities, generosity, vows, righteousness, observances, and truth, along with the eight attributes, are always present in the possessed person, in part or in full, according to the power of the graha.85

21. Grahas do not cohabit [saṃviśanti] with humans, nor do they possess [āviśanti] people, and those who say they do possess them are to be disregarded because of confusion with respect to knowledge of bhūtas [bhūtavidyā].86

22. There are virtually infinite numbers of night-stalking attendants of these grahas, who devour blood, fat, and flesh, and are very frightening, and it is they who possess [āviśanti] him.87

23. With respect to those night-stalkers whose condition is determined by various classes of deities [devagaṇam], because of their connection with that [deity’s] nature they are to be known as anointed by them.

24. In addition, those who are described as deity grahas [devagrahāḥ] are impure, though honored and invoked as deities.

25. Each of these classes of grahas, beginning with the gods, has the nature, actions, and behavior of their respective masters. One should keep in mind that they are the offspring of the daughters of Chaos [nirṛti].88

26. The behavior of those who have strayed from truthfulness is shaped by the multitudes of these [daughters of Nirṛti] who are generally intent on injury as sport or divine states [devabhāvam].

27. The designation bhūta was given to them by the experts in such terminology; in this way the physician [ bhiṣak] knows bhūtas who are designated graha by this term.

28. This, then, is called the “science of bhūtas” [bhūtavidyā], and with this knowledge the physician [vaidya] is very intent in his desire to pacify them.

Aṣṭāṅgahṛdayasaṃhitā 6.4.1–44:

Now we shall narrate a chapter on the understanding of bhūtas as the sages Ātreya and others told it long ago.

1. One should take note of a person’s knowledge, understanding, speech, movement, strength, and humanity. Whenever in a man there is an absence of humanity, one might say there is a bhūta graha.

2. By the tenor of one’s appearance, temperament [prakṛti], speech, gait, etc., which one assumes in conformity with a bhūta, one may conclude that he is possessed [āviṣṭam] by that bhūta.

3. There are eighteen types, according to divisions such as deva, dānava, etc. When a person is in their grip, the cause may be immediate or it may be due to a previous action.89

4. An extreme transgression of one’s better judgment [prajñāparādhaḥ],90 wherein one’s ordained life-style, religious vows, and proper behavior are transgressed, may be due to lust and so on. In such a case, one also offends honorable men.

5. Uncontrolled [bhinnamaryādam] in this way the transgressor becomes self-destructive. The gods and others also attack, and the grahas strike at his weak points.

6–8. These weaknesses include undertaking a transgressive act, the ripening of an undesirable action, residing alone in an empty house, or spending the nights in burning grounds and other similar places;91 public nudity, maligning one’s guru, indulgence in forbidden pleasures, worship of an impure deity, contact with a woman who has just given birth,92 and disorder with respect to tantric or Purāṇic fire offerings [homa], the use of mantras, sacrificial offerings not involving fire [ bali], vedic sacrificial offerings [ijya], and positive actions or rites that counter negative ones [parikarma]; as well as a composite neglect of prescribed conduct in the form of daily routine and so on.

9. The gods [surāḥ] possess [gṛhṇanti] a man on the first or thirteenth day of the waxing lunar fortnight, the dānava seizers on the thirteenth day of the waxing lunar fortnight or the twelfth day of the waning lunar fortnight.

10. However, the gandharvas [possess] on the fourteenth and the serpent demons [uragāḥ] on the twelfth and fifth days, while the Lords of Gifts [dhaneśvarāḥ, i.e., yakṣas] [possess] on the seventh and eleventh days of the waxing fortnight.

11. Brahmarākṣasas [possess] on the fifth and eighth days of the waxing fortnight as well as on the full-moon day, while [ordinary] rakṣases, piśācas, etc., [possess] on the ninth and twelfth days of the waning fortnight as well as on either the new-moon or full-moon days.

12. The deceased ancestors [pitaraḥ] [possess] on the tenth day and the new moon day, while the others, including gurus, elders and others [guruvṛddhādayaḥ] [possess] on the eighth or ninth days. In general, the time at which [possession] should be noted is at dawn and dusk [saṃdhyāsu].

13–15. One whose face is like a lotus in bloom, whose gaze is soft, who is without anger, who speaks little and has little sweat, feces, and urine, who has no craving for food, who is devoted to the gods and the twice-born, who is pure and possessed of refined speech, whose eyes blink infrequently, who has a sweet scent and grants boons, who is fond of white garlands and clothes and enjoys dwelling by rivers or on high peaks, who does not sleep, and who is inviolable is regarded as one who has been brought under the influence of the devas.

16–17. One whose gaze is crooked, who is evil-natured, who is inimical toward his gurus, the gods and the twice-born, who is fearless, conceited, strong, angry, and resolute, who goes around saying, “I am Rudra, Skanda, Visākha; I am Indra,” who savors liquor and meat is regarded as possessed [gṛhītakam] by a daitya graha.

18–19b. One whose behavior is good, who has a sweet scent, who is blissful, who engages in song and dance, who takes delight in bathing and gardens, who wears red clothes and garlands, and adorns himself with red oils, who enjoys erotic play is said to be inhabited [adhyuṣitam] by a gandharva.

19c–21b. One whose eyes are red, who is angry, whose gaze is fixed, whose gait is crooked, and is unstable, whose breathing is incessantly short, whose tongue dangles and shakes, licking the corners of his mouth, who likes milk, jaggery, bathing, and who sleeps face down is regarded as inhabited [adhiṣṭhitam] by serpent demons [uraga], being fearful of sunlight as well.

21c–24b. One whose eyes are red, swimming, and fearful, whose scent is clean and energy is bright, who is fond of dance, storytelling, song, bathing, fine garlands and oils, who enjoys fish and meat, who is blissful, contented, strong, and intrepid, who shakes his finger saying “What shall I give to whom?,” who tells secrets and mocks physicians and the twice-born, who is irritated by small matters and has a swift gait is regarded as possessed [gṛhītakam] by a yakṣa.

24c–26b. One who is fond of laughter and dancing, whose gestures are wild [raudra], who excoriates others’ weaknesses, who is abusive, fast-moving, who is inimical toward the gods and the twice-born, who beats himself with sticks and knives, etc., who [hypocritically] addresses others with the respectful term bhoḥ and recites the sastras and Vedas is regarded as possessed [gṛhītam] by brahmarākṣasas.

26c–29. One whose eyes are filled with anger, whose brows are furrowed, revealing agitation, who assaults others, who runs around with a fearful visage making a racket, who is strong without taking food, whose sleep is disturbed and who wanders about in the night, who is shameless, impure, heroic, and violent, who speaks harshly, who is irritable, who is fond of red garlands, women, blood, wine, and meat, who licks his chops after seeing blood or meat, and who laughs at mealtime is said to be one who is inhabited [adhiṣṭhitam] by a rākṣasa.

30–34b. One whose thoughts are unhealthy, who runs around, not remaining in one place, who is fond of leftovers, dancing, gandharvas, laughter, wine, and meat, who becomes depressed when rebuked, who cries without reason, who scratches himself with his nails, whose body is rough and voice trails off, who trumpets his many miseries, whose speech freely associates what is relevant and irrelevant, who suffers from memory loss, who enjoys nothing, who is fickle and goes around desolate and dirty, wearing clothes meant for the road, adorned with a garland of grass, who climbs on piles of sticks and rocks93 as well as on top of rubbish heaps, and who eats a lot is understood to be inhabited [adhiṣṭhitam] by a piśāca.

34c–35b. One refers to a man whose appearance, actions, and scent are like those of a preta, who is fearful and dislikes food, and who has many minor imperfections94 is regarded as possessed [gṛhītam] by a preta.

35c–36b. One who chatters incessantly, has a dark face, is late wherever he goes, whose scrotum is swollen and dangling is said to be inhabited [adhiṣṭhitam] by a kūṣmāṇḍa.95

36c–38. One who wanders around in rags taking up sticks, clods of dirt, etc., [or] runs around naked, with a frightened look, adorned with grass, haunting burning or burial grounds, empty houses, lonely roads, or places with a single tree, whose eye forever embraces sesame, rice, liquor, and meat, and whose speech is rough is believed to be inhabited [adhiṣṭhitam] by a niṣāda.

39. One who begs for water and food, whose eyes are fearful and red, and whose speech is violent is a man known to be afflicted [arditam] by an aukiraṇa.96

40. One who is fond of fragrant garlands, speaks the truth, shakes, and sleeps a lot is believed to be under the control of a vetāla.97

41–42. One whose visage is detrimental, whose countenance is dispirited, whose palate is dry, whose eyelashes quiver, who is sleepy, whose natural effulgence is dull, who wears his upper garment over the right shoulder and under the left arm, who is fond of sesame, meat, and jaggery, and who stammers is believed to be under the control of a deceased ancestor [pitṛgraha].

43. One whose anxieties are consistent with the curse of a guru, elder [vṛddha], ṛṣi, or siddha may describe his own speech, diet, and movements in terms of that graha.

44. One should abandon a person who is followed by a crowd of children, is naked and whose hair [ mūrdhajam] is disheveled, whose mind is abnormal, and who has been possessed [sagraham] for a long time.

The Psychodynamics of Bhūtas

I must now evaluate two important critiques of the material on bhūtavidyā presented in the āyurvedic texts: the first by Mitchell Weiss, the second by Terry Clifford. Weiss, as we have seen, deals with the data presented in the texts translated above. Clifford discusses material presented in a Tibetan text called the Gyu-zhi (rGyud-bzhi) (The Four Tantras), “the most famous and fundamental work in Tibetan medical literature.”98

Let us first consider Weiss’s study, which summarizes the symptoms of unmāda according to the type of graha possessing the individual. Occasionally he supplements these with psychoanalytic interpretations. For example, with respect to unmāda caused by devagrahas he states that the devas “cause one to see, possibly indicating a paranoid delusion or hallucination, or perhaps an autoscopic hallucination.”99 Furthermore: “In the deva and guru et al. types hyperpious, obsessive-compulsive, and paranoid symptomatology are characteristic suggesting rigid internalized controls, preoccupation with the cultural values, and a psychodynamically significant role for guilt. There are hallucinations, and paranoid schizophrenia has been suggested.”100 Weiss continues, cogently, that the arrangement of the types of graha, in Caraka at least, “suggests a successively decreasing capacity for organized social functioning and a decreasing influence of internalized control mechanisms.”101 To this statement he adds that the sequentiality of the indigenous categories reveals “the psychodynamic significance of obsessive-compulsive, anal personality traits which yield to oral and then phallic narcissistic psychodynamics.”102 These observations, in my view, fail to consider local context, especially for the deva and guru types, namely, possession as devotional practice. In this context, the “decreasing capacity for organized social functioning and a decreasing influence of internalized control mechanisms” deviate from the norm, as he states, but the incipient context sanctions such emotionally laden behavior as derivative of devotional practice. Thus, to label this particular set of psychodynamics obsessive-compulsive, phallic narcissistic, and so on, is to fix both a taxonomy and a set of values on an experience, in this case the devagraha experience, which misstates, ignores, or downplays its cultural locus and significance as deviant behavior. Similarly, such preemptive classification ignores complementary passages in the āyurvedic texts that describe equivalent personality types not regarded as the product of possession.

Let us turn briefly to some of these passages, which present a de facto argument for bhūtas as substantialized collocations of personality attributes. The primary passage in question is from Caraka’s Śārīrasthāna (CaSā 4.36–40),103 the section that describes embryology. This passage details the generation, construction, and development of the body (śarīra), describes different types of sattvas, essences or intelligences, as the final ingredient in the construction of the body. It is important to note that the canonical āyurvedic compendia are inclusive texts: they contain everything from creation mythology to diagnostics to anatomy (as in the present case) to descriptions of innumerable physical conditions to surgery (in Susruta only) to a broad range of therapies, including ritual, dietary, and pharmaceutical.104

I refer to sattvas (states of being) as “essences,” or, following Meulenbeld, “personality types.”105 CaŚā 4.36 states that “sattvas are of three types: pure [suddham], dynamic [rājasam], and slothful [tāmasam].106 Among these, the pure (personality type) is said to be faultless [adoṣam], bearing a degree of auspiciousness. The dynamic [type] is said to be defective [sadoṣam], because it bears some anger. The slothful [type] is said to be defective, because it possesses a certain degree of delusion.” Caraka continues that these categories reveal dominant modes, within which individuality is manifested by unique mixing or texturing of the three. In some cases the personality follows the body’s tendency toward any one of these three, while in others the reverse is found—the body responds to the dominant tendency of the personality. Caraka then subdivides these categories into seven suddha types, six rājasa types, and three tāmasa types.

The suddha types have a clear affinity for divinity. These include: (1) the brāhma type, with the qualities of brahmā, is given to purity, passionlessness, tolerance, good memory, and so on; (2) the ārṣa, with the qualities of ṛṣis, is given to ritual performance and keeping vows and are hospitable, eloquent, free from anger, and so forth; (3) the aindra, with the traits of Indra, is brave, regular in performing rituals, authoritative in speech, generous, virtuous, and so on; (4) the yāmya, one with the qualities of Yama, are economical in action, self-motivated, is free from attachment and negative qualities; (5) the vāruṇa, one with the qualities of Varuṇa, is brave, patient, pure, religious, generous, fond of water, and proper in exhibition of anger and pleasure; (6) the kaubera, one with the qualities of Kubera, exhibit prestige, wealth, philanthropy, purity, and recreation; (7) the gāndharva personality type, who, like a gandharva, is fond of song and dance, poetry and epic narration, scents, garlands, women, and passion.

The six rājasa and three tāmasa personality types are closer to the accounts of grahas given in the texts. The rājasa types include: (1) the asura, with the qualities of an asura, is brave, powerful, cruel, lordly, and intolerant; (2) the rākṣasa, resembling a rākṣasa, is intolerant, angry, violent, envious, and fond of sleep, indolence, and nonvegetarian food; (3) the paisāca, one with the qualities of a piśāca, is gluttonous, lustful, dirty, cowardly, prone to poor dietary habits; (4) the sārpa, one with the qualities of a sarpa or snake, is brave when wrathful but otherwise cowardly, indolent, but with sharp reactions, and fearful when eating and walking; (5) the praita, with the traits of a preta or spirit of the dead, is always hungry, exhibits extreme suffering, is envious, indiscriminate, and excessively greedy; (6) the sākuna, one with the habits of a sakuni or bird of ill omen, is attached to passion and overeating, and is unsteady and ruthless, yet is nonacquisitive.

The three tāmasa essences or personalities include: (1) the pāsava, whose nature is like that of a beast (pasu), is one whose actions are wasteful, is unintelligent, has disgusting habits and diet, and is excessively interested in sleep and sex; (2) the mātsya, who resembles a fish (matsya), is cowardly, unintelligent, hungry, unsteady, passionate, wrathful, fond of water and constant movement; (3) the vānaspatya, whose personality resembles a vegetable (vanaspati), is indolent, always hungry, devoid of intelligence or any of its attributes.

Thus, the texts describe personality patterns as both products of birth and forms of madness. In both cases the characteristic behavior must be manifested as habitual, spontaneous, and nonritual. The only way to tell one from the other, apparently, is that in the latter madness diagnosed as exogenous, the characteristic behavior appears as a sudden and marked change that then becomes habitual, spontaneous, and nonritual. In addition, what confers on the possessed individual the psychophysiological identity of a graha is not just antisocial behavior in the case of a few of these grahas but an āyurvedic diagnosis of humoral imbalance that distinguishes their current condition from their earlier psychophysiological norm (prakṛti). In this case the unmāda may be diagnosed as exogenous (āgantuka) or inherent (nija), in the latter case attributable to identifiable causes other than possession, rendering it medically treatable.

The descriptions of grahas and sattvas, possessing entities and personality types, are noteworthy because of their close resemblance. They elucidate a differentiation not only in order to expose various abnormalities but also to express a sense of variation within the field of personality. The identification of these sattvas as independently or exogenously materialized grahas, which appears to have inspired in the authors of the āyurvedic texts a greater need to describe them graphically, is a kind of cultural phenomenology that in part harks back to the associative thinking of the vedic Brāhmaṇas and Upaniṣads. The linking of the infestation of certain grahas with days of the lunar month in the AH and elsewhere, and the systematic stigmatization of certain personality types as possessed who suffer from social aggravations, such as disrespect for brahmans, are also indicative of this. Whether one is possessed or otherwise, whether natural or exogenously acquired personality, one can well imagine engaging in normal social relations with individuals of many of these categories, including the deva, gandharva, rākṣasa, uraga, yakṣa, and several others.

As suggested, it is the intensity of the experience as well as its suddenness, which according to Āyurveda distinguishes an identifiable pathology from possession by a graha. In moderation, then, many of these behaviors reflect psychological conditions (as distinguished from sociological ones) that were not particularly aberrant within norms that were deemed culturally acceptable in classical India, but that nonetheless signaled danger that in extreme forms were regarded as pathological. It is for this reason that I question the impulse to unhesitatingly resort to Western psychoanalytic labeling. It is by no means certain that classical Indian sociocultural contexts would consistently yield to this sort of labeling. Thus, I am uncomfortable with Weiss’s full-scale application of psychoanalytic categories because he does not demonstrate their necessity in the sociocultural milieu of classical India. His method might have been more convincing if he had attempted to demonstrate the viability and applicability of a few carefully selected Freudian categories based on a cultural study of Dharmasāstras and Sanskrit literature.107

Weiss might legitimately counter that the fact of possession is not the point; rather, the point is that the descriptions conform with Freudian psychoanalytic categories. My rebuttal, however, would then be twofold: first, in the Indian context they do not necessarily conform with Freudian psychoanalytic categories; second, and conversely, these categories shed little light on unmāda or possession from an Indian or āyurvedic perspective. Simply put, the success of any methodological or interpretative framework in cross-cultural analysis depends on its addressing discourse modes and epistemological issues on both sides of the divide. One thing that neither Weiss nor any other Freudian interpreter of Indic culture has attempted to understand on its own terms is the Indian notion of the dynamics of the interpenetration of the world of spirit with the world of matter. The usual strategy has been to wave it away with a Freudian wand, which, quite simply, is inadequate.108 Therefore, I would not agree with Weiss’s acceptance of Jane Murphy’s conclusion in which she disputes the argument that cultural relativism as a factor in evaluating deviance is sufficient to undermine the notion that there are typologies of “affliction shared by virtually all mankind.”109

Now, let us turn to Terry Clifford’s inquiry into the “psychiatric” aspect of Tibetan medicine. It is contemporaneous with Weiss’s study, but is not at all in the same vein. Although Clifford’s book appeared in 1984, she conducted her research in 1976–77,110 a fact worth noting because it appears that the application of Freudian psychodynamics to Asian medical systems peaked at about that time.111 Clifford, a psychiatric nurse who took such a great interest in Tibetan medicine that she traveled to Nepal to study with Tibetan doctors, based her extensive study on the Gyu-zhi. This work was originally written in Sanskrit by Candranandana, who lived in the eighth century and also composed a commentary on the AH.112 Indeed, the Gyu-zhi is based to a great extent on the AH, a fact that Clifford notes, though, curiously, she did not utilize the AH in her study, much to the detriment of her work.113 Candranandana’s work was probably translated into Tibetan shortly after its composition. Chapters 77–79 of the third Tantra of this text are devoted to demonology.114 Clifford’s project is designed to elucidate the text in the framework of Tibetan Buddhist psychological principles, but she also occasionally enters into discussions of its resonances with Freudian and other psychoanalytical theories.