2

“HELL, THERE ARE NO RULES HERE—WE’RE TRYING TO ACCOMPLISH SOMETHING.”

THE MENLO PARK LABORATORY—where Edison and his experimenters improved the telephone, invented the phonograph, and developed a commercial electric light and power system—was the world’s best-equipped private industrial research facility in the late 1870s and early 1880s. Edison’s transformative inventions, by themselves, do not fully represent Menlo Park’s significance, though. At Menlo Park, Edison combined three elements that shaped his approach to innovation for the rest of his life: team-based research, corporate support for research and development, and the branding of his persona as a reliable, practical inventor, in order to encourage investor financing of his laboratories and inventions.

A dispute with a landlord motivated Edison’s move to Menlo Park. Edison had rented space in a Newark padlock factory on a monthly basis, and when he no longer needed it, he gave notice and returned the keys at the end of the month. The landlord sued Edison under an ordinance that made monthly renters responsible for a full year’s rent. Outraged at the injustice of this law, Edison decided to leave Newark.

On December 29, 1875, Edison purchased two tracts of land in Menlo Park, a small village of 200 residents and a stop on the Pennsylvania Railroad, located twenty-five miles south of New York City and seven miles north of New Brunswick, New Jersey. On one of those tracts, between January and March 1876, Edison’s father, Samuel, supervised the construction of a two-story laboratory. On Edison’s other tract, closer to the railroad, stood a light-colored frame house with red trim, where Edison moved with Mary, their daughter, Marion, and their infant son, Thomas Jr.

Edison’s home at Menlo Park, summer 1881.

In 1878 the Philadelphia Times described the Menlo Park laboratory:

A frame tenement, nearly one hundred feet long, two stories high and without sign or ornament, it looks like a white frame country school house pulled out three times its own length. Two brick chimneys rise from one of its sides. A pond of rain water is just beside this building, and also one big tree, the whole enclosed by a paling fence, making a lot of an acre or more.

The first floor contained a drafting room and library, a machine shop, a blacksmith’s shop, and a carpentry shop. New York Sun journalist Amos Cummings, who compared the laboratory to an “old fashioned Baptist tabernacle,” colorfully described the second floor as

an immense laboratory filled with electrical instruments. A thousand jars of chemicals were ranged against the walls. A circle of kerosene lamps was smoking on an empty brick forge. Their chimneys were the essence of blackness. An open rack loaded with jars of vitriol [metal sulfates] stood in the middle of the room, and the rays of the sun struck through them, flecking the floor with green patches. The western end of the apartment was occupied by telephones and other instruments, and there was a small organ in the southwestern corner.

Cummings spotted Edison at a table in the center of the room. “His hands were grimy with soot and oil, his straight dark hair stood nine ways for Sunday, his face was beardless but needed a shave, his black clothes were seedy, his shirt dirty and collarless and his shoes ridged with red Jersey mud.”

Reporters asked Edison why he moved to Menlo Park. “I couldn’t get peace and quiet and was run down by visitors,” he answered. “I like it first rate out here in the green country and can study, work and think.” Edison answered the question well enough but took the opportunity to express his antipathy toward urban life. “I may add that it is becoming the universal experience of men of professional or mental strain that they cannot stand the publicity of cities, the gassy hospitality and intrusive vealiness of adolescent club people, idiotic paragraphers and female men.” Menlo Park’s seclusion allowed Edison and his experimenters to avoid the distractions of cities. However, the laboratory’s proximity to the railroad gave them easy access to the people and resources that made cities the centers of innovation.

Reporters nicknamed the Menlo Park laboratory the “invention factory,” where Edison vowed to produce “a major invention every six months, a minor one every six weeks.” But Menlo Park was not a factory. Factory owners valued productivity and discipline and used time clocks and rigid work rules to govern worker behavior on the factory floor. Worker autonomy and independence were discouraged.

Nineteenth-century machine shops, in contrast, were innovative environments. Machinists were skilled artisans who enjoyed more independence and autonomy than factory workers. They owned their tools and, in a system called “inside contracting,” could negotiate compensation with shop owners. As a result, machinists had more control over the work process and production schedules than factory workers. Machine shops valued quality of workmanship over quantity and supported creativity by encouraging independence, informality, and individual initiative.

The informality of the machine shop work culture promoted new ideas and helped transfer technological knowledge. Following an apprenticeship under an experienced master, where they learned their trade, many machinists became itinerant, moving from city to city and shop to shop in search of work. As they moved around, they brought their skills with them. Independent inventors could rent access to tools and equipment and hire machinists to help them develop and test new inventions.

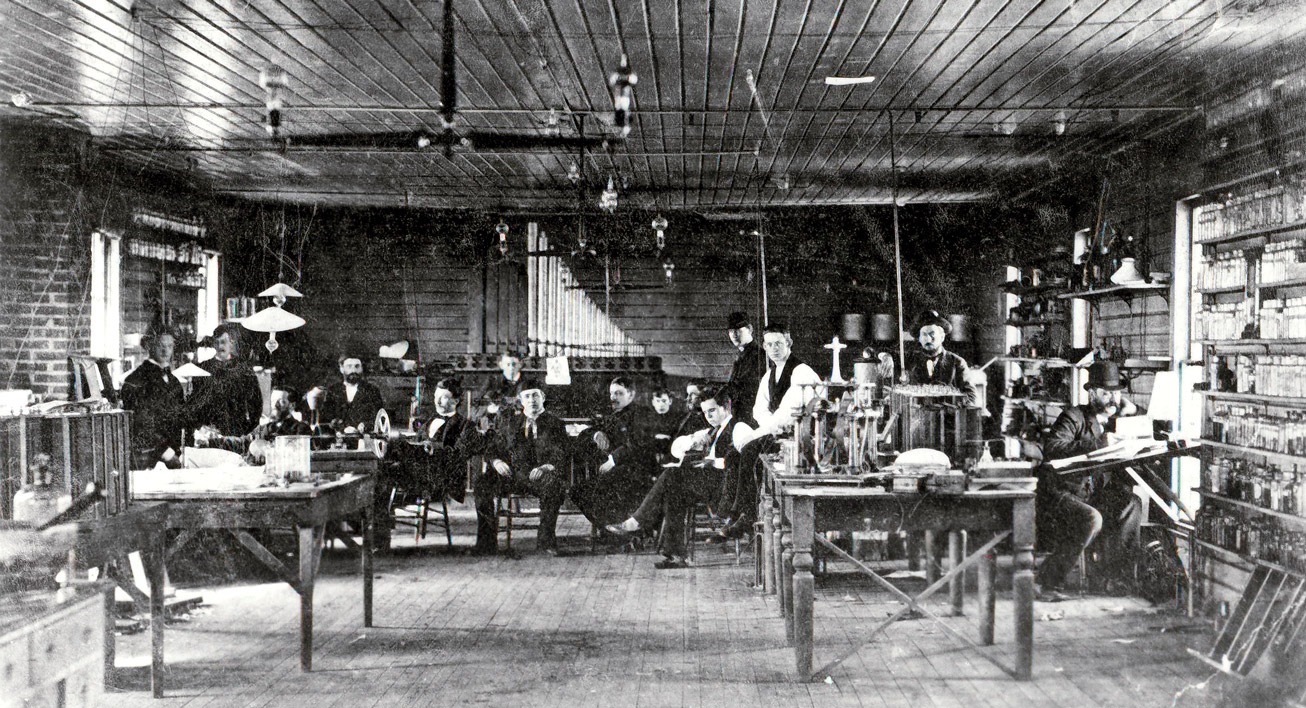

The Menlo Park lab (left) and the brick office and library (right) in 1880. The library housed the technical literature Edison gathered to support his electric light research. (From the collections of The Henry Ford)

Edison and his staff on the second floor of the Menlo Park lab, 1880. Francis Jehl remembered that Edison often played the organ in a “pick and hunt style” during late-night suppers.

At Menlo Park, Edison brought together all the tools, equipment, information, and skilled artisans he needed to turn ideas into practical inventions. Although he relied heavily on the values and practices of the machine shop culture to utilize these resources in an innovative manner, Edison’s ability to motivate experimenters to pursue a common agenda was key to his success. By providing leadership and determined laboratory goals, he impelled experimenters to pursue his ideas, not their own. As Edison explained in testimony for an electric light patent lawsuit in September 1881, he did not tell his workers how to solve problems; he expected them to think for themselves. “I generally instructed them on the general idea of what I wanted carried out, and when I came across an assistant who was in any way ingenious, I sometimes refused to help him out in his experiments, telling him to see if he could work it out himself, so as to encourage him.”

Edison’s principal Newark machinists, Charles Batchelor, John Kruesi, James Adams, and Charles N. Wurth, came with him to Menlo Park. Wurth was a Swiss machinist who had worked for the Singer Sewing Machine Co. before joining Edison in the fall of 1870. He had gone back to Switzerland in 1872 with a letter from Edison recommending him as “a steady and ingenious man,” only to return to Edison in the fall of 1873.

These machinists formed a core group of about 200 employees who worked with Edison over the years between 1876 and 1882. During Edison’s first two years at Menlo Park, there were no more than a dozen employees on the payroll. This number increased in 1878, when Edison hired more workers to assist with the electric light project. Workers came to Menlo Park for different reasons. Some wanted technical experience; others merely wanted jobs. Some of Edison’s employees came only for a short time; others, like machinist John Ott, remained with Edison for the rest of their lives.

Work life at Menlo Park was not governed by the factory time clock. As Charles Clarke, an electric light experimenter, later recalled, “Laboratory life with Edison was a strenuous but joyous life for all, physically, mentally and emotionally. We worked long hours during the week, frequently to the limit of human endurance; and then we had time off from Saturday to late Sunday afternoon for rest and recreation.”

In December 1878, Edison asked Sarah Jordan, a stepsister of Mary Edison, to run a boardinghouse for his workers. Edison wired the house for twenty incandescent lamps in August 1880.

The staff typically worked six days a week, ten hours a day, and sometimes late into the night. On those occasions Edison treated his workers to a midnight snack, followed by songs, jokes, and storytelling. Francis Jehl recalled, “During the midnight lunches, Edison often went to the organ and played a tune in the ‘pick and hunt’ style. One of the boys who could play would give us some of those old tunes of yesterday and all of us, including Edison, sang.” These midnight breaks promoted a sense of community and camaraderie. Charles Clarke was impressed with the baskets of food brought in for the workers: “Not a cold lunch, mind you, but a hot dinner of flesh or fowl with vegetables, dessert and coffee. Hilarity increased with the filling of stomachs, bantering and story telling were interlarded. At length Edison stood up, stretched, took a hitch at his waistband and began to saunter away—the signal that dinner was over, and work would be resumed.”

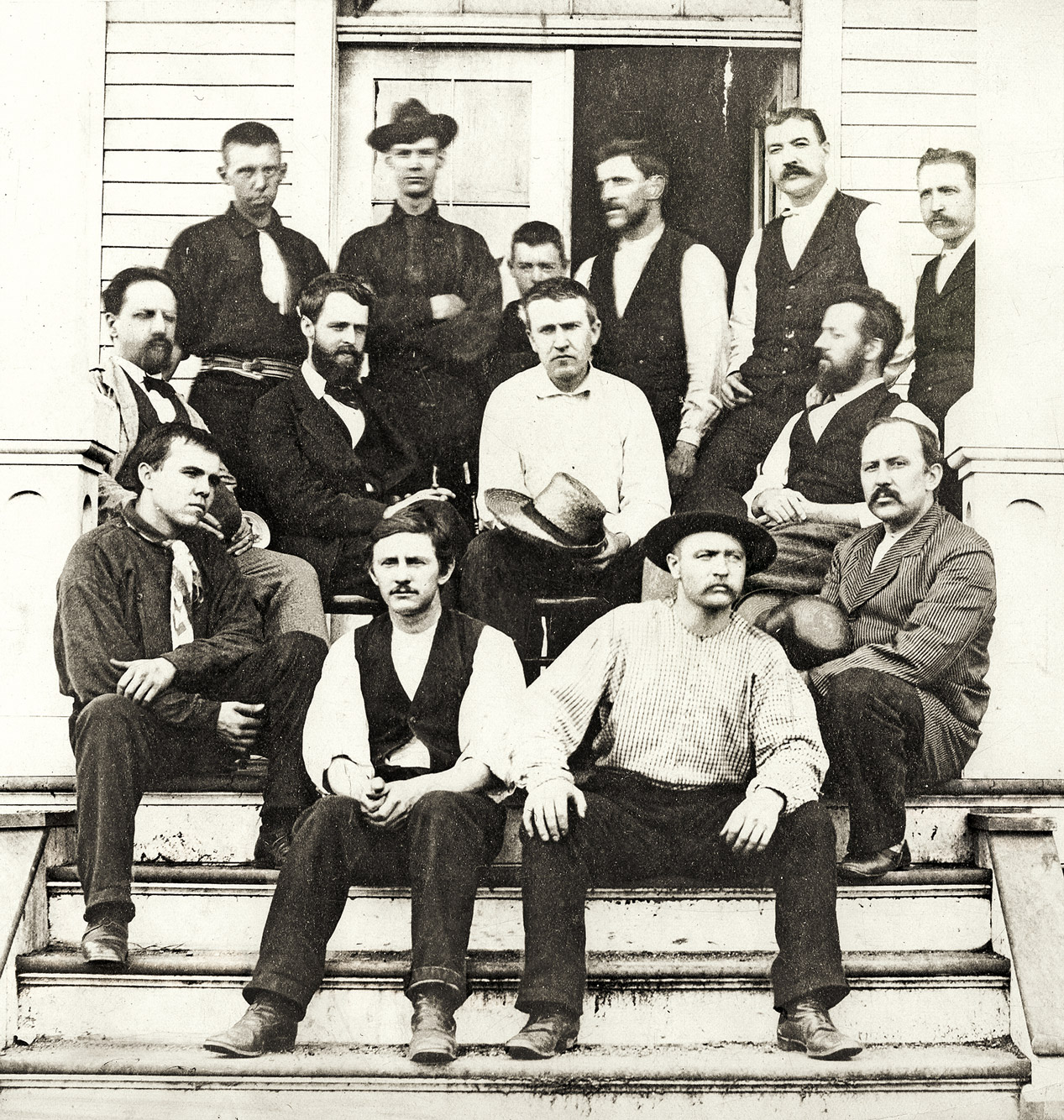

Edison (center, holding straw hat) with his experimenters on the porch of the Menlo Park lab, 1880.

Edison’s capacity for hard work inspired loyalty and teamwork. “We work all night experimenting & sleep till noon in the day,” Charles Batchelor wrote his brother in September 1875. “We have got 54 different things on the carpet & some we have been on for 4 or 5 years. Edison is an indefatigable worker & there is no kind of a failure however disastrous affects him.” In April 1879 another experimenter, Francis Upton, wrote to his father about the difficulties of electric light research. “Mr. Edison will overcome them if any does. I have not in the least lost my faith in him for I see how wonderful the powers he has. He holds himself ready to make anything that he may be asked to make if it is not against any laws of nature. He says he will either have what he wants or prove it impossible.”

Without corporate sponsorship, the Menlo Park laboratory would have been a well-equipped but isolated machine shop. Edison’s track record as an inventor and manufacturer of telegraph technologies in the early 1870s demonstrated to the telegraph industry managers that invention was more than the ad hoc activity of unreliable inventors; it could be organized and managed to achieve the marketing goals of corporations.

William Orton, the president of Western Union, was a significant figure in this change. In the early 1870s independent inventors still developed most new technologies and, to market them, either sold their patents to existing companies or raised capital to organize their own companies. In 1870 Western Union created the position of electrician, which helped the company evaluate new telegraph technologies, but it did not have the ability to develop its own inventions. Edison’s talents as an inventor, combined with his ability to create and manage productive and innovative laboratories, convinced Orton that supporting Edison would give Western Union a competitive advantage.

A contract Edison signed with Western Union in December 1875 to finance research on acoustic telegraphy gave him the resources to construct and equip the Menlo Park laboratory. On January 29, 1877, Edison drafted a letter to William Orton proposing regular financial support for the operation of the laboratory. “At present the cost of running my machine shop including coal, kerosene and labor is about 15 per day or 100 per week. At present I have no source of income which will warrant continuing my machine shop and I shall be compelled to close it unless I am able to provide funds,” he explained to Orton. Edison proposed that Western Union pay him $100 per week ($2,220 today) to operate the machine shop in exchange for control of his telegraph inventions.

This proposal resulted in a five-year contract, signed on March 22, 1877, in which Western Union agreed to pay Edison $150 per week ($3,320 today) for laboratory expenses in exchange for control of his telegraph inventions. Western Union also agreed to pay Edison royalties on any inventions it adopted and to cover all patent and lawyer fees. In exchange, Edison was required to appoint Western Union’s counsel, Grosvenor P. Lowrey, as his Patent Office representative. Lowrey later played an important role in securing the financing for Edison’s electric light research (see Chapter 4).

Edison depended on his reputation as a reliable inventor to maintain investor confidence in the profitability of industrial research laboratories as a source of new technologies—and he relied on newspapers to promote this reputation. Americans in the late nineteenth century were fascinated by new technologies, and newspaper editors were eager to satisfy public curiosity by publishing articles about Edison’s laboratories and inventions. Rather than cultivating publicity because of ego or self-aggrandizement, Edison gave reporters access to the laboratory and kept his name, image, and persona before the public for practical purposes. This early “branding” activity was directed not just to the public, but also to potential investors.

At times, Edison was uncomfortable with press attention, particularly when reporters interrupted important experiments. He also did not like sideshow-type publicity. This became evident in March 1888, when he objected to the advertising schemes of his British phonograph agent, George Gouraud. “I am well aware of the value of the assistance which the press are capable of giving us, but it appears to me wholly unnecessary to make a parade after the fashion of Barnum and his white elephant.”

Gouraud wanted to mount a phonograph exhibition in London and publish a book about Edison. Edison approved the exhibition but rejected the book idea. “I have no objection whatever to you advertising the phonograph to any extent you please, but personally I have no desire for notoriety and do not wish to be included in arrangements which are distasteful to me, and which, at least in America, would be undignified.”

Edison’s “chalk receiver” telephone. According to legend, Edison’s preferred telephone greeting was “Hello.” Bell’s choice, “Ahoy,” never caught on. (Photograph © SSPL/Science Museum)

EDISON’S FIRST MAJOR EXPERIMENTAL PROJECT at Menlo Park was designing an alternative to Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone. Edison’s telephone research was based on his work with the acoustic telegraph, an instrument that used different sound tones to transmit multiple telegraph messages over one wire. Edison began acoustic telegraph research in the fall of 1875 with the financial support of Western Union. Edison and Elisha Gray—an electrical engineer employed by the Western Electric Manufacturing Co. in Chicago who also experimented with acoustic telegraphy—came close to developing an acoustic telegraph capable of transmitting speech, but their primary goal was the transmission of sound.

Carbon button telephone sketch. By carefully dating and signing his notes and drawings, Edison protected his ideas in case of patent litigation.

In June 1876, two Edison associates saw a demonstration of Bell’s telephone at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition. Edison later claimed that he had begun working on the telephone in May (he executed a patent application for a “telephonic telegraph” on May 9), but reports of Bell’s invention prompted him to intensify this work during the summer and fall of 1876. Western Union wanted to develop its own telephone network to compete with Bell, and by early 1877, the development of an alternative to Bell’s instrument became a major research project at the Menlo Park Laboratory.

Edison’s telephone work focused on improving Bell’s transmitter. Bell’s telephone used a metal diaphragm and a wire-wrapped magnet to transmit speech. The voice caused the diaphragm to vibrate, which produced an induced current in a wire, which re-created the vibrations at the receiving end and allowed a listener to hear the speech. Bell’s telephone, however, produced a weak signal. Edison believed that this was caused by the weakness of Bell’s induced current, and he experimented with ways to strengthen the signal by fluctuating or varying the current’s resistance. To produce variable resistance, he developed a carbon-based transmitter.

Edison spent much of his time in 1877 and early 1878 searching for suitable forms of carbon and testing different telephone component arrangements. He also created more complex electric circuits than Bell used in his system, and also designed an induction coil, which allowed the telephone signal to be transmitted over longer distances.

In the spring of 1878, Western Union purchased the rights to Edison’s telephone patents for $100,000 ($2.3 million today) and organized the American Speaking Telephone Co., which installed Edison’s telephone in several U.S. cities. When Western Union sued the American Bell Telephone Co. for patent infringement, however, the courts upheld Bell’s patent. In 1879, Western Union and the Bell Co. reached a compromise: in exchange for royalties on its patents, Western Union agreed to withdraw from the telephone business. Under this arrangement, Edison’s telephone patents were transferred to the Bell Co.

Edison branded his consumer products with his name, image, and distinctive umbrella signature.

Record keeping was essential to Edison’s approach to innovation. It allowed him to document experimental work, preserve contractual rights with business partners, track the finances of his laboratories and companies, and secure patent protection for his inventions. Edison recognized the value of record keeping as early as 1870, when he wrote on the inside back cover of a pocket notebook, “All new inventions I will hereafter keep a full record.”

Thomas Edison National Historical Park preserves more than five million documents relating to the development of Edison’s inventions. At the heart of these records are the 3,500 standard notebooks Edison and his employees used to record laboratory experiments. In the early 1870s Edison kept notes on whatever was available, including ledger books, pocket notebooks, and loose scraps of paper. There was no attempt to systematize record keeping until the Menlo Park laboratory began electric light experiments in the fall of 1878. The complexities of designing the electric light system and the number of experimenters working on the project required Edison to adopt a standard six-inch-by-nine-inch laboratory notebook, which Edison and his experimenters used to sketch ideas and track the results of experiments.

Edison often used laboratory records to protect and defend his patents against infringement, but the notebooks were more than just potential legal evidence; they enabled experimenters to communicate with one another and transfer ideas and concepts. Edison and his staff used rough sketches to explore solutions to technical problems on paper and to convey them to the machinists and mechanics in charge of creating three-dimensional models.

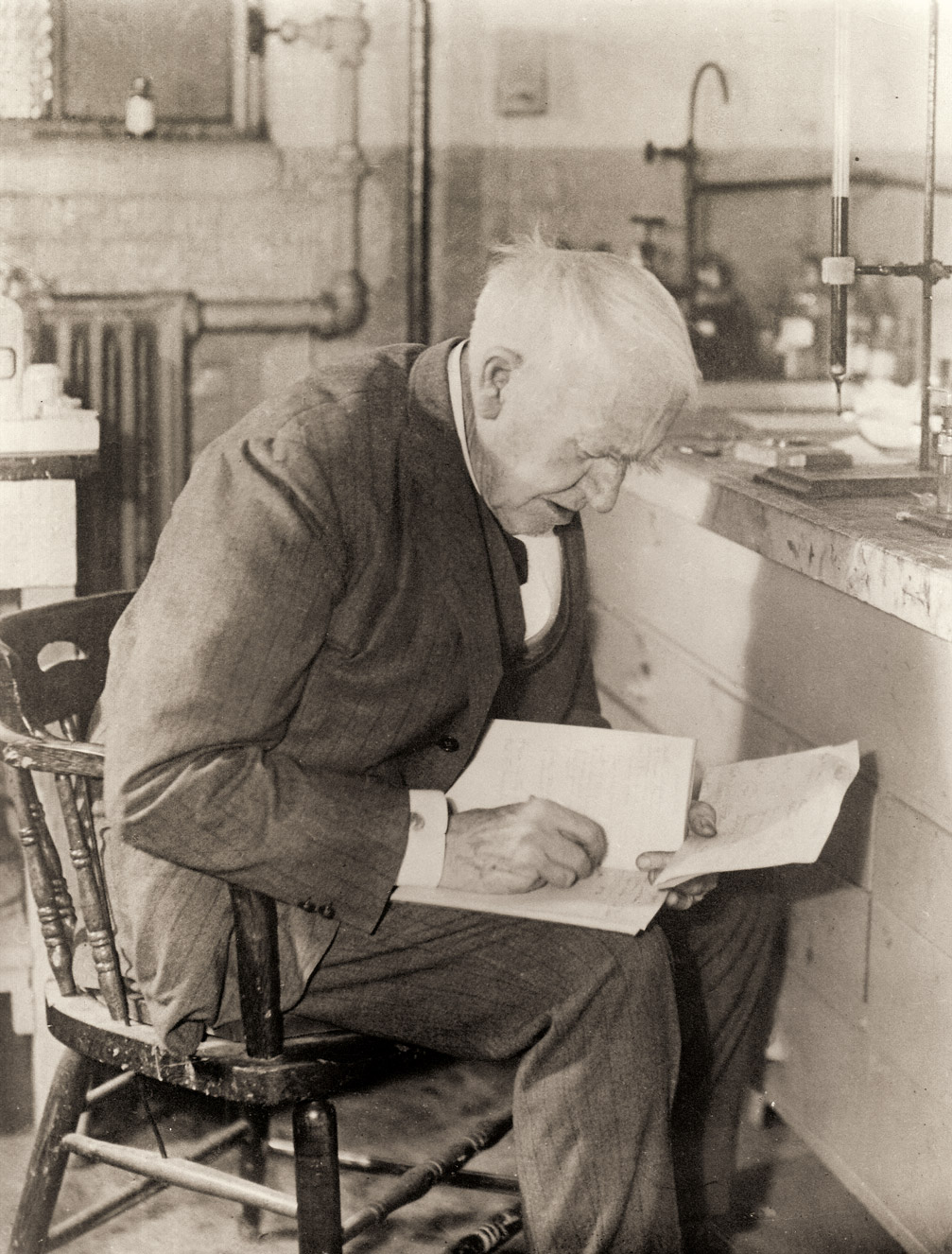

Because the standard-size notebooks were communal, many of them contain notes and sketches from multiple experimenters. For his own private notes, Edison used pocket notebooks as early as the late 1860s, when, as a telegrapher, he sketched ideas for improved telegraph circuits, tracked his spending on tools and supplies, and kept track of the books he read. There are 330 pocket notebooks in the Edison archives—most of them filled by Edison at West Orange from 1887 to 1931.

Edison’s pocket notebooks allowed him to record ideas as he moved around the laboratory and between factories, conferring with experimenters and production managers. They contain page after page of to-do lists, instructions for his staff, ideas for new inventions, and experiments for improving existing products. They show that Edison did not innovate from one desk.

Edison taking notes on rubber research at West Orange, December 1928.

Edison’s technical notes and drawings, like this telephone sketch and list of projects, allow us to see how his laboratories designed new inventions. (Christopher Bain)