3

“I’VE MADE SOME MACHINES; BUT THIS IS MY BABY, AND I EXPECT IT TO GROW UP TO BE A BIG FELLER AND SUPPORT ME IN MY OLD AGE.”

POPULAR CULTURE OFTEN PORTRAYS the act of invention as a sudden flash of insight or inspiration that leads to new ways of doing things. Charles Batchelor described such a “eureka” moment when Edison discovered the idea of recording sound on July 17, 1877, while they worked on ways of storing and retrieving telephone messages. As he handled a telephone diaphragm—a thin membrane used to convert speech to electromagnetic waves—Edison proposed an experiment: “If we had a point on this,” he told Batchelor, “we could make a record on some material which we could afterwards pull under the point, and it would give us speech back.”

Edison and his staff often tried many approaches until they found the right solution. In this March 1878 note, Edison drew different ideas for recording diaphragms.

Batchelor attached a metal point to the center of the diaphragm and mounted it on a piece of grooved wood. Edison pulled a strip of waxed paper through the groove as he spoke into the diaphragm. “On pulling the paper through a second time,” Batchelor recalled, “we both of us recognized that we had recorded speech.”

Edison’s voice vibrated the diaphragm, causing the metal point to indent sound waves on the waxed paper. They reproduced speech by reversing the process. Edison noted the next day, “There’s no doubt that I shall be able to store & reproduce automatically at any future time the human voice perfectly.”

Edison considered recording sound on strips of waxed paper in the summer of 1878 before eventually using sheets of tinfoil wrapped around a cylinder.

Edison’s discovery of sound recording was a new insight shaped by prior experience—especially his work on the acoustic telegraph, the telephone, and the translating embosser, an instrument that recorded or “embossed” long telegraph messages on grooved paper discs placed on a revolving plate. Through his work on the acoustic telegraph and the telephone, Edison had gained familiarity with the physical properties and behavior of sound. Robert Spice, a Brooklyn chemistry teacher, had instructed Edison on acoustics in 1875, and Edison owned a copy of Herman von Helmholtz’s influential study of acoustics, sound, and music theory, On the Sensations of Tone (1863). Edison may also have known of the phonautograph, an instrument invented in 1857 by French scientist Leon Scott that traced sound waves on a paper cylinder coated with lampblack (the sooty residue deposited on kerosene lamps).

The first tinfoil phonograph, now in the museum collection of Thomas Edison National Historical Park. (Christopher Bain)

Edison continued sound recording experiments during the summer and fall of 1878. He tried recording sound on paper of different thicknesses coated with various waxes and even attempted to record on the edge of the paper instead of the flat side. He also modified the size and shape of the recording points and diaphragms. In these early experiments, Edison tested different formats, including spools of paper tape and spirally grooved paper discs. By mid- September, he was focused on designing a cylinder recording machine, and by early November, he had envisioned recording on a sheet of tinfoil wrapped around a metal cylinder that would “indent about 200 spoken words & reproduce them from same cylinder.” On November 29, Edison gave a sketch of this machine to John Kruesi, who spent six days making a model.

Kruesi finished the task on December 6. The tinfoil phonograph was a hand-cranked cylinder mounted between two diaphragms. Metal points attached to the phonograph with thin watch springs were placed between the diaphragms and the cylinder. On that day, Edison took a sheet of tinfoil, wrapped it around the brass cylinder, turned the crank, and spoke into the recording diaphragm. His first words were a verse from the children’s nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” Edison’s voice caused the diaphragm to vibrate the metal point, which indented sound waves on the tinfoil sheet. He reversed the process to listen to the recording, turning the cylinder back to the starting point, placing the reproducing point over the recorded groove, and turning the crank. To his astonishment, the phonograph worked on the first trial.

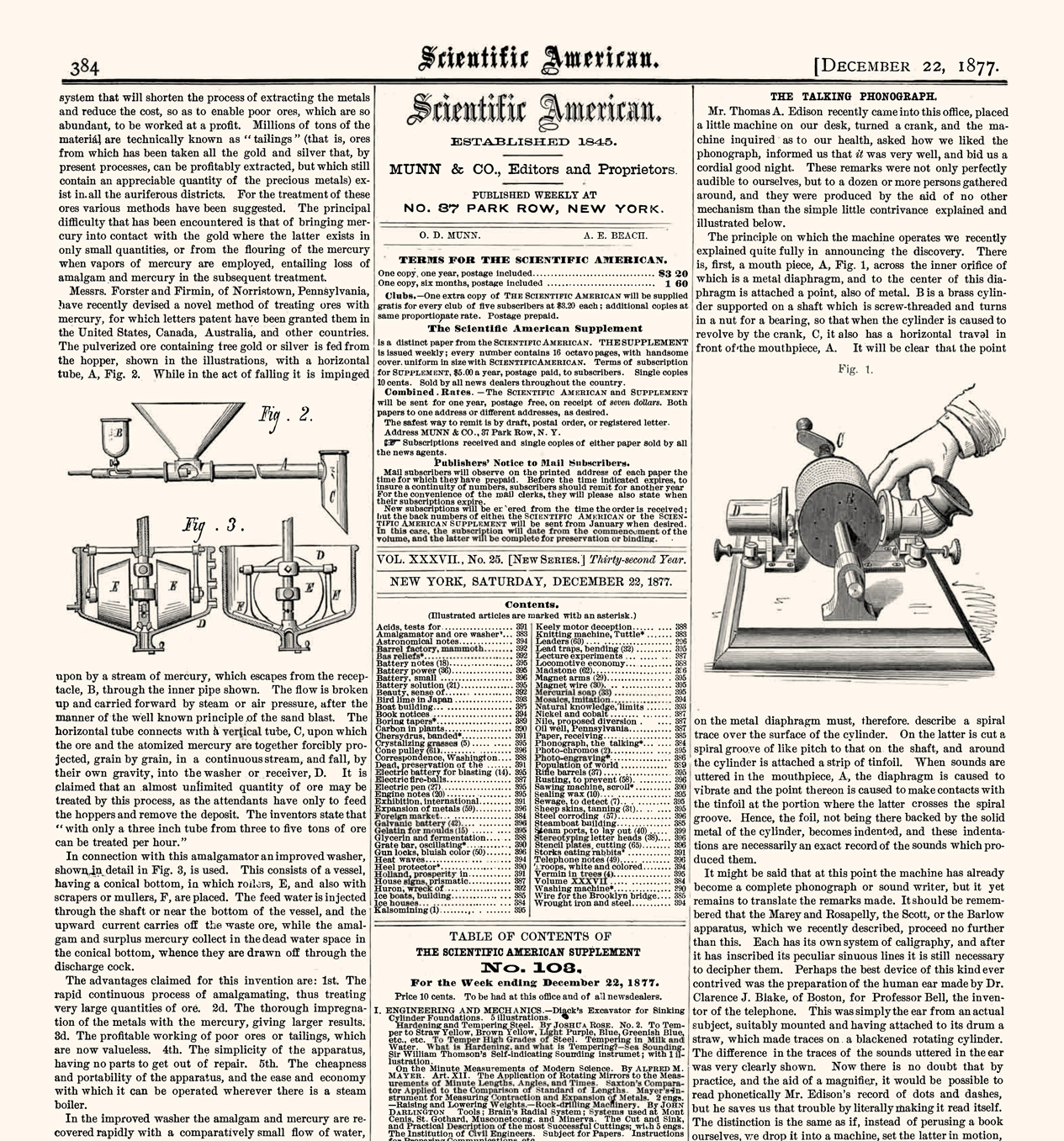

Edison and his staff wasted little time in publicizing the phonograph. Edison associate Edward Johnson described the process in a November 6 letter to Scientific American, the leading technical publication in the United States, and on December 7, Batchelor sent a description of the tinfoil phonograph to the editor of the English Mechanic. After Edison demonstrated the tinfoil phonograph for the editors of Scientific American, a report published in December by the journal described the event: “Mr. Thomas A. Edison recently came into this office, placed a little machine on our desk, turned a crank, and the machine inquired as to our health, asked how we liked the phonograph, informed us that it was very well, and bid us a cordial good night.” The machine surprised the editors, who remarked, “No matter how familiar a person may be with modern machinery . . . it is impossible to listen to the mechanical speech without his experiencing the idea that his senses are deceiving him.”

Scientific American, the leading technical journal in the United States in the nineteenth century, published the first description of Edison’s tinfoil phonograph on December 22, 1877. News of the invention created a media sensation and made Edison a celebrity. (Private Collection)

Following the Scientific American account, American and international newspapers published stories about the tinfoil phonograph and its inventor. Up until the end of 1877, Edison had been a well-known figure within the relatively small community of telegraph industry managers and engineers. While aware of Edison, the public probably did not know much about his work. The phonograph changed that. Press accounts created a sensation, bringing Edison international fame. As a result of this publicity, the Menlo Park laboratory was flooded with fan mail and requests for the new invention.

Several correspondents in early 1878 expressed interest in using the phonograph for scientific research. Stevens Institute of Technology professor Alfred M. Mayer wanted to use the phonograph in his acoustic experiments. As he wrote to Edison, “The results are far reaching (in science), its capabilities are immense & I cannot express my admiration of your genius better than by frankly saying that I would rather be the discoverer of your talking machine than to have made the best discovery of anyone who has worked in acoustics.” Physician Clarence Blake thought the phonograph would be useful for studying speech and diseases of the larynx.

Alexander Graham Bell took an early interest in the tinfoil phonograph. He respected Edison’s achievement but believed that his own work on the telephone had brought him close to discovering the principle of sound recording himself. As he wrote his father-in-law in March 1878, “It is a most astonishing thing to me that I should possibly have let this invention slip through my fingers when I consider how my thoughts have been directed to this subject for so many years past.” Bell tested a phonograph to determine if it could be used for speech education but found the tinfoil recording inadequate for distinguishing certain vowel sounds, and he concluded that the phonograph was an interesting but deficient toy.

During the first months of 1878, Edison and his associates demonstrated the phonograph in Menlo Park, New York City, Washington, D.C., and other eastern U.S. cities. At the end of December 1877, Edison exhibited the machine for Western Union. Demonstrations were staged at Cooper Union and the Fifth Avenue Baptist Church in New York. Edward Johnson hosted exhibitions in Rhode Island and several upstate New York towns, including Elmira, Dunkirk, and Jamestown. “At all places great enthusiasm is shown over both the telephone and phonograph,” Johnson reported. “When they hear the phonograph reproducing my song with its imperfections they endanger the walls with the clamor.”

In April Edison went to Washington, D.C., to present the phonograph to the annual meeting of the American Academy of Sciences, held at the Smithsonian Institution, and to members of Congress. He proudly posed with the phonograph in a photograph taken at the studio of Civil War photographer Matthew Brady. The Washington trip culminated with a late-night White House demonstration for President Rutherford B. Hayes. As Edison recalled for his authorized biography, “The exhibition continued till about 12:30 A.M., when Mrs. Hayes and several other ladies who had been made to get up and dress, appeared. I left at 2:30 A.M.”

During an April 1878 visit to Washington, D.C., a proud Edison poses with his tinfoil phonograph at the Matthew Brady studio.

Edison enjoyed demonstrating the tinfoil phonograph, but questions about its commercial development required attention. At the end of December 1877, he appointed Theodore Puskas, a Hungarian promoter, as his European sales agent. On January 7, 1878, Edison signed two contracts covering the manufacture and marketing of phonographs for specialized applications. One agreement, with Oliver Russell, covered the use of toy phonographs. The other contract gave Daniel Somers and Henry Davies the right to sell talking clocks and watches. In exchange for these rights, Edison would receive a 10 percent royalty on each phonograph sold. Nothing came from these contracts.

On January 30, 1878, Edison gave a group of investors that included Alexander Graham Bell’s father-in-law and Bell Telephone Co. founder Gardiner Hubbard the exclusive right to market phonographs in the United States. In exchange, Edison received a 20 percent royalty on each tinfoil phonograph sold and $10,000 ($233,000 today), which he agreed to apply toward developing the phonograph into a “satisfactory apparatus for dictating letters or reproducing musical compositions.” On April 24, Hubbard and his partners organized the Edison Speaking Phonograph Co. in Connecticut.

This arrangement allowed Edison to outsource marketing responsibilities to company organizers and gave him the resources to improve the phonograph in the laboratory. Menlo Park constructed prototypes of different tinfoil phonograph models, but throughout 1878 Edison contracted out machine production to shops in Newark, New York, and Philadelphia. Shifting marketing and manufacturing to business associates and contractors enabled Edison to focus on technical design, an area of strength, but it also meant that he could not completely control sales strategy or production quality. Edison changed this approach in the early 1880s, when the complexities of introducing his electric lighting system required him to become more involved in manufacturing and marketing.

Mark Twain was one of the most popular performers on the late-nineteenth-century lecture circuit. Before movies, radio, and TV, these lectures provided entertainment and introduced the public to new technologies, such as the telephone and phonograph. (Library of Congress)

THE LACK OF a clearly defined application for the phonograph affected the company’s ability to promote it. Edison’s contract with the Edison Speaking Phonograph Co. mentioned entertainment and business applications but did not offer specifics. Edison and his associates considered a variety of applications for the phonograph. Along with using it as a telephone answering machine—as referred to in early experimental notes—Edison proposed several uses, including talking dolls and animals, music boxes, and talking clocks. Edison also speculated about employing the phonograph to record courtroom testimony and to play recorded sidewalk advertisements. In an article published in the May–June 1878 issue of North American Review, “The Phonograph and Its Future,” Edison identified several potential applications, including speech education and talking books for the blind.

In April 1878 Edison told a reporter from the Philadelphia Weekly Times his idea of recording novels on the phonograph and described a “reading” experience similar to today’s audiobooks. “Well, the phonograph will read poetry to you, if you are sick, or your eyes are weak or you cannot stand the light. It will read in dark or light. It will read a whole novel and re-read it so that ladies sewing can hear a story read off.” Edison claimed that he could produce talking books at a much lower cost than printed versions. “I can furnish a novel pricked that way for three cents instead of fifty cents, the price of a paper novel, because the composition is not in type, but in punctures.”

The tinfoil phonograph, however, could not do any of these things in 1878. Operating the instrument required a high level of skill and patience. The recording was not very loud or distinct, and the tinfoil sheet was delicate and easily damaged. Recordings could be reproduced only once or twice, and it was difficult, if not impossible, to store the recording for any length of time. Edward Johnson summarized the phonograph’s condition in January 1878: “The phonograph is creating an immense stir but I think it impresses people more as a toy than as a practical machine.”

Lacking a practical machine, the company decided to capitalize on the invention’s novelty, but its managers debated whether they should sell or lease phonographs or establish a business demonstrating the phonograph to the public. Gardiner Hubbard preferred selling phonographs, but Edward H. Johnson, the company’s general agent, pushed for exhibitions. Charles Cheever, another company manager, argued that “there could be quite a number of thousands of dollars made . . . by exhibiting the phonograph at once” and advocated licensing demonstrators in exclusive territories. Hubbard did not oppose phonograph exhibitions, but he believed that it would be difficult to organize and manage a national network of exhibitors. Responding to daily requests for machines and the need to generate revenue to pay mounting expenses, on April 2 Hubbard announced plans for agents of the American Bell Telephone Co. to sell large exhibition phonographs for $100 each ($2,330 today).

A few weeks later, Hubbard changed his mind about phonograph exhibitions. After attending a phonograph demonstration in Washington in mid-April, James Redpath, the organizer of the Redpath Lyceum Bureau in Boston, offered to establish a phonograph lecture business. Established in 1868, Redpath’s Lyceum Bureau arranged for prominent authors and public figures—including Mark Twain, Henry Ward Beecher, and Frederick Douglass—to give lectures in cities and towns throughout the United States. It was a popular form of adult education and entertainment, and it was profitable for the bureau and the speakers. In the 1870s, new technologies, such as the telephone, were introduced to the public through traveling lectures and demonstrations. Hubbard, appreciating the popularity of public lectures, accepted Redpath’s offer of “introducing the phonograph to the public, by a series of lectures carried on simultaneously in different parts of the country.”

Redpath began organizing phonograph exhibitions in May 1878. The Edison Speaking Phonograph Co. issued circulars, offering interested parties the exclusive right to exhibit the phonograph for up to three months in assigned territories. The exhibitors, who paid $100 for the privilege of demonstrating talking machines, charged the public twenty-five cents for admission. The company took 25 percent of the receipts.

In September 1878, Redpath reported that his exhibition business had earned over $7,000 ($163,000 today), but he closed his Irving Hall demonstration in New York City after two weeks because of poor attendance. “It has been liberally advertised but it does not pay,” Redpath told Hubbard. “Mr. Johnson, of course, believes that if we hold on we shall soon have crowded houses. I don’t. There have been upwards of 300 exhibitions of the phonograph in this city & I think the interest is exhausted.”

George Bliss, who organized an exhibition business in Illinois, experienced similar problems. Bliss rented a store on Chicago’s fashionable State Street to stage phonograph demonstrations and spent $200 ($4,650 today) to promote them through newspaper ads, street banners, and posters. However, he could not compete against more popular forms of entertainment and concluded that public interest in the phonograph had diminished.

By early January 1878 Edison had introduced several improvements to the tinfoil phonograph, including a larger cylinder, an amplifying funnel, and a flywheel to regulate the cylinder’s speed. Further research in early 1878 focused on designing a small, inexpensive demonstration phonograph capable of recording up to fifty words. By March 1878 Edison was selling the smaller model for $30 ($698 today). He expected to sell a large number of these demonstration machines, but they did not work satisfactorily and only a few were sold.

The small demonstration phonograph was designed to generate revenue until the Menlo Park laboratory could complete what it hoped would become the standard model: a disc phonograph operated by a clockwork mechanism. Edison expected the clockwork phonograph to alleviate the problem of uneven speed produced by hand-driven machines. Steam-operated phonographs tested in January and February 1878 showed promise, but steam was not a practical power source. Edison completed a clockwork disc machine by early April, but it did not perform adequately, so he abandoned the disc format.

That month, Edison included a clockwork mechanism in a cylinder. Along with a clockwork motor, this machine featured a pendulum speed regulator, bearings to improve the positioning of the recording diaphragm and cylinder, and a moveable slide bar to attach the tinfoil more securely to the cylinder. On May 19, Edison wrote to Theodore Puskas, “the clockwork cylinder machine is running today & it works splendidly. I shall probably ship it next Saturday.” Although Edison incorporated the clockwork design in a British patent specification, for unknown reasons he never marketed a clockwork cylinder phonograph.

Edison and Batchelor made their last serious attempt to improve the tinfoil phonograph at Menlo Park in early October 1878, when they sketched a design for a dictating machine featuring a vertically mounted cylinder containing a roll of tinfoil. By placing the foil inside the cylinder, Edison hoped to simplify the process of applying foil sheets to the machine. Sketches and patent drawings reveal that a clockwork motor would have powered the machine, which included controls to allow operators to start and stop recording at will. Edison told the New York Sun that this machine could record up to 4,000 words. “Any man can dictate to it at his leisure, and his office boy can run out a half dozen or dozen words, stop the machine by pulling the cord, and write out what is desired,” he declared. The Edison Speaking Phonograph Co. hoped that this new version of the phonograph would revive their business.

Although the laboratory prepared measured drawings of this design and incorporated its features in a March 1878 patent application, Edison did not put the machine into commercial production.1 By the fall of 1878 the Edison Speaking Phonograph Co. noticed a decline in sales and expressed concern about the public’s disinterest in the phonograph. From October to November 1878, phonograph sales dropped from $2,305 to $1,065. In November Edison gave Edward Johnson a loan to gain control of the company from its original investors. Johnson planned to sell a small demonstration phonograph he was developing with Sigmund Bergmann, a former Edison employee who operated a manufacturing shop in New York, but interest in the tinfoil phonograph continued to diminish. Sales rose slightly in December but declined steadily between January and July of 1879. On January 21, 1879, the Edison Speaking Phonograph Co. canceled its contract with Edison. He received his last royalty statement in August 1879. By then, Edison was involved in electric light research. He would not return to the phonograph until 1886, shortly before opening his West Orange laboratory. The tinfoil phonograph failed in the market during the late 1870s for several reasons. The Edison Speaking Phonograph Co. did not focus on an application for the phonograph that would guide its technical improvement or enable the company to implement an effective marketing strategy. The company vacillated between different functions (entertainment vs. business) and different marketing policies (sales vs. leasing). In its efforts to improve the tinfoil phonograph, the Menlo Park laboratory focused on the machine, not the recording medium. Without a record that could be easily handled or stored—a problem Edison would address at West Orange—the phonograph was a machine of limited utility. Consequently, the Edison Speaking Phonograph Co. relied on limited and fleeting markets: a public interested in the phonograph as a novelty and a small group of scientists who looked to the talking machine as an instrument for acoustic research.

Amid public acclaim for the invention of the tinfoil phonograph, the Daily Graphic nicknamed Edison the “Wizard of Menlo Park” on April 10, 1878.

MARION EDISON REMEMBERS MENLO PARK

Edison’s oldest daughter, Marion, considered her childhood at Menlo Park one of the highlights of her life. As she recalled in 1956, shortly before her eighty-fourth birthday, “The laboratory had a queer fascination for me and I was never happier than when there.” The lab’s second floor and glassblower’s house particularly fascinated her, but she never entered the machine shop, fearing that the machinery would catch her long blond hair.

“It was one of my daily duties to bring up father’s lunch to the laboratory,” she remembered. “I always peeked into the basket to see what he had and never failed to find a piece of pie so big that it covered the sandwiches.”

Marion spoke most vividly about the phonograph. “I will never forget the day after the phonograph was invented. The men were all absent getting some rest after an exciting night. One lonely man was still there and when he turned the crank of the cylinder and ‘Mary Had a Little Lamb’ came clearly out in my father’s voice, I jumped up and down for joy.” She noted the streams of visitors who came to see the phonograph, including the famous French actress Sarah Bernhardt.

Of her home life, Marion remembered living in a three-story Victorian house run by three servants and a coachman “who lived in an apartment over the stable.” When Thomas and Mary’s third child, William Leslie, was born, on October 26, 1878, she was disappointed that the new baby was not a girl. “My brother Tom was a sickly, delicate child, and had to spend his winters in Florida, so was never a playmate.”

Marion described her mother as a beautiful blonde who enjoyed giving lavish parties for her friends and family and wearing expensive clothes. “I still have photographs of some of the costumes Lord & Taylor made for her,” Marion recalled. “One unusual one was a red and black brocade, decorated with stuffed red birds with black wings.”

Despite the parties, Mary was lonely at Menlo Park. “My father neglected her for his work, or so it seemed to her. He never would come to her parties and he would often skip meals and very often would not come until early morning or not at all.”

With Edison absent much of the time, Mary slept with a revolver under her pillow for protection. For the second time in his life, Edison was almost shot one night when he came home late. “Father forgot the front door key and not wanting to awaken the whole household, he climbed up the trellis onto the porch roof to his bedroom window. Mother, thinking he was a burglar, almost shot him. She let out a scream which father heard, then he called out to her, thus preventing a catastrophe.”

Sarah Bernhardt asked to meet “le grand Edison” during her 1880 U.S. tour. During her December 5 visit to Menlo Park, an enthralled Bernhardt asked if Edison was married. (Félix Nadar)