4

EDISON’S ELECTRIC LIGHTING SYSTEM

“THE ELECTRIC LIGHT IS THE LIGHT OF THE FUTURE—AND IT WILL BE MY LIGHT—UNLESS SOME OTHER FELLOW GETS UP A BETTER ONE.”

IN THE FALL OF 1878, the Menlo Park laboratory began tackling a problem that inventors had unsuccessfully addressed since the 1840s: the development of a practical incandescent electric light. Edison and his team not only invented an incandescent lamp; they also designed a system for producing and distributing electric light and power and created companies to manufacture and market this system in the United States and other countries. These early Edison electric light companies were the basis of the modern electric power industry.

British scientist Humphry Davy discovered the principle of arc and incandescent lighting in the early 1800s when he found that certain materials, when heated to incandescence by electricity, emitted light. He also demonstrated that electricity flowing through a circuit connected to two carbon rods separated by a gap produced a bright light.

LEFT: In 1809 British chemist Humphry Davy invented the first electric arc light. (The Granger Collection) RIGHT: Six years later he introduced a safe open-flame lamp for coal miners. (Science Source: Sheila Terry/Science Photo Library)

Russian engineer Paul Jablochkoff introduced the first practical arc lighting system in the late 1870s. The harsh arc lights, however, were more suitable for outdoor and large indoor spaces. This limitation encouraged inventors to “subdivide” the electric light by designing smaller, less bright lamps for interior residential and commercial spaces.

Edison was aware of the problem. In September 1877 he brought a strip of carbonized paper to incandescence, but exposure to air quickly oxidized and burned the carbon. To prevent oxidation, Edison attempted to place the carbon in a vacuum, but he lacked an efficient vacuum pump and dropped the experiment.

On September 9, 1878, Edison traveled to Ansonia, Connecticut, with Charles Batchelor, University of Pennsylvania professor George Barker, and a newspaper reporter to visit William Wallace’s brass factory. Earlier that summer, on a trip to the western United States, Edison and Barker had had long conversations about harnessing waterfalls to generate electricity and transmitting the power over long distances to operate mines. Barker had encouraged Edison to visit Ansonia to see Wallace’s arc lighting system and new generator.

According to the New York Mail, Edison was excited by Wallace’s system. He “ran from the instruments to the lights and from the lights back to the instrument. He sprawled all over a table with the simplicity of a child, and made all kinds of calculations.” Edison returned to Menlo Park convinced that he could solve the problem of “subdividing” the electric light.

Edison’s solution was a regulator that would prevent a lamp’s element from melting or burning by momentarily cutting off the electric current before the element overheated. He envisioned electric lamps wired in a parallel circuit instead of in series, which would enable regulators to control their own lamps and allow consumers to turn off individual lamps without shutting down the entire system.

On September 13, Edison included these ideas in a patent caveat and telegraphed to Wallace: “I have struck a big bonanza.” Batchelor wrote to a coworker, “We have struck a big thing on Electric Light & I think we have solved the problem of the subdivision of it so that we can make as many lights of small power as we like.” Edison told the New York Sun, “I have it now. When it is known how I have accomplished my object, everybody will wonder why they have never thought of it, it is so simple.”

Edison drew these electric lamp sketches in September 1878, several months before he decided to put the burner inside a glass vacuum.

Edison predicted that his electric light would provide illumination at a lower cost than gas lighting. His system would supply businesses and residences with light and power generated at a central location. He envisioned lighting large sections of lower Manhattan. “The same wires that bring the light to you will also bring power and heat. With the power you can run an elevator, a sewing machine or any other mechanical contrivance that requires a motor and by means of the heat you may cook your food,” Edison told the New York Sun.

Following news reports of Edison’s “breakthrough,” the price of gas lighting company stocks declined on the New York and London stock exchanges. In late September, Edison’s attorney, Grosvenor P. Lowrey, began negotiating with a group of potential investors that included Western Union president Norvin Green; Drexel, Morgan & Co. partner Egisto P. Fabbri; and business leaders associated with New York Central Railroad president William H. Vanderbilt. These talks resulted in the October 16 incorporation of the Edison Electric Light Co., capitalized at $300,000 ($6,440,000 today). Edison gave the company exclusive control of his North and South American electric light patents. In return, he received $250,000 in company stock, $30,000 ($698,000 today) for experimental costs, an additional $100,000, and a five-cent royalty on each lamp the company sold, with a guaranteed annual minimum of $15,000.

Headquarters of the Edison Electric Light Co. at 65 Fifth Avenue, New York City.

Lowrey—who was instrumental in creating the corporate organization to fund Edison’s research—also acted as an intermediary between Edison and his investors. The directors of the Light Co., believing Edison had already solved the electric light problem, grew impatient when he failed to unveil his new lamp. Lowrey reassured Edison, who bristled at the lack of faith, and advised him to be honest with the company about the challenges he faced and arranged visits to Menlo Park for company officials.

Despite initial optimism, Edison was months away from introducing a practical electric light. As the Menlo Park staff worked on lamp regulators in the fall of 1878, they realized they would have to design an entire system—not just a lamp—including switches, meters, a distribution system, and, because Edison was dissatisfied with Wallace’s dynamo, a new generator.

Edison also had to determine the system’s technical requirements. This involved studying existing electric light technology and understanding the costs of gas and arc lighting systems. Edison hired Francis Upton to review the scientific and technical literature and the patents covering the field. Upton came to Menlo Park with an academic background in mathematics and science. He had degrees from Bowdoin College and Princeton and had spent a year studying in Berlin with German scientist Hermann von Helmholtz.

In November 1878, the laboratory designed its first light meter, which would allow electric light companies to measure customer electricity consumption. In December, experimenters began designing a new generator. Edison had identified platinum as the most promising material for the lamp’s burner, but it was scarce and expensive. In January 1879 he began testing gold, iridium, nickel, and other metals to find a substitute, and concluded that platinum was still the best metal. He thus began a more systematic study of the properties of platinum—part of a larger effort to understand how platinum behaved under incandescent conditions.

In early 1879, Edison made two decisions that changed the direction of lamp research. After failing to prevent a platinum wire from disintegrating under incandescence, he decided to place the wire inside a vacuum. Edison had tried this in 1877, but he now had access to equipment that allowed him to produce better vacuums. The other shift was Edison’s decision to design a lamp with a filament of high resistance. (Resistance refers to the ability of a material, like copper or aluminum, to allow the passage of electricity.) Because of Ohm’s law, elements in low-resistance lamps required lots of current to reach incandescence, which meant that conductors would have to be either very short or thick. A high-resistance lamp needed less current, enabling Edison to design longer, thinner conductors and reduce the overall cost of the system.

Placing lamp filaments in a high-vacuum glass globe prevented oxidation, but the expansion of gases in the platinum cracked the wire as the electricity heated it. Edison solved this problem by driving the gases off slowly as he gradually heated the wire in a vacuum. A greater challenge was finding an insulating material that would adhere to the platinum wire and prevent it from overheating.

By March, the laboratory had designed a lamp consisting of a platinum wire enclosed in a glass vacuum. Edison thought that he had succeeded in inventing a practical lamp and, after a small demonstration at Menlo Park late that month, began making plans for an even larger demonstration. His experimenters, however, had not yet found a way to prevent the platinum wire from melting. Another problem was the scarcity of platinum. In the spring of 1879, Edison sent hundreds of circular letters to postmasters in mining districts, asking for information about deposits of platinum ore. Work on designing generators, meters, and a distribution system continued during the spring and summer.

Despite progress on other system components, the laboratory had not yet designed a practical platinum lamp by the fall of 1879. The failure to produce an insulating material for the platinum wire was a significant obstacle. In early October the laboratory began experiments on filaments made out of carbon. Why Edison and his team tried carbon is unclear. It was a common material in nineteenth-century laboratories, and Edison used it in his carbon button telephone transmitter. In early October, Batchelor molded a spiral filament out of tar and lampblack and slowly baked it in an oven to carbonize it. Tests of the carbon revealed that it might meet Edison’s requirements for high resistance. Later that month, Batchelor tested a variety of carbonized material, including fishing line, cardboard, and cotton soaked with tar. He achieved the best results with carbonized cotton thread. On October 22, 1879, a lamp with a carbonized cotton thread burned for thirteen and a half hours.

Employees of the Edison Lamp Works at Menlo Park, New Jersey, 1880.

BATCHELOR’S LONG-BURNING CARBONIZED FILAMENT was the breakthrough Edison needed to complete a practical incandescent electric lamp, but it was not the end of research, as experimenters at Menlo Park continued to work on improving the lamp and other system components. On December 21, 1879, the New York Herald published the first account of the carbon lamp. During the last week of December, hundreds of visitors came to Menlo Park to see a light display that Edison had constructed at the laboratory. The railroad added extra trains to the schedule to accommodate the crowds. According to the Herald, “The laboratory was brilliantly illuminated with twenty-five electric lamps, the office and counting room with eight, and twenty others were distributed in the street leading to the depot and in some of the adjoining houses.”

Edison’s lab notebooks offer windows into the creative process. On these pages, Edison and Batchelor collaborate on the design of lamp filaments.

From New York, news of Edison’s accomplishment spread across the United States and around the world. Peter Dowd, a telegraph line contractor from Boston, wrote Edison on December 27: “Whenever I go downtown I am met by somebody or other who want to know what I think about your light . . . little of anything else, comparatively speaking, has been talked about in this city during the last week.” Alfred Taylor wrote Edison from Chester, Pennsylvania, on January 3, 1880: “I have attentively read the numerous and various detailed accounts that have from time to time appeared in the newspapers, and am anxiously waiting the final step to be taken that will crown your indefatigable efforts with undoubted success to furnish to the world a cheaper and better light.”

For Edison to furnish a better light to the world, he needed companies to manufacture and market the system. The Edison Electric Light Co. controlled Edison’s patents, but its directors were reluctant to invest money in manufacturing operations, preferring instead to sell licensing rights to the new technology. Edison believed that he would have to manufacture the system in his own shops to control costs and to continue to improve electric lighting technology and production methods. Lowering production costs would help make the Edison electric lighting system more competitive.

Early Edison lamps were simply plugged into a wooden base. The Menlo Park lab designed the more secure screw-type lamp socket familiar today. (Christopher Bain)

In April 1880, Edison purchased an abandoned factory near the Menlo Park laboratory to manufacture lamps. Workers began producing vacuum pumps, while the laboratory staff continued improving the lamp. Menlo Park experimenters designed improved lamp sockets, developed techniques for testing defective filaments, and designed the tools to make filaments in large quantities. The laboratory also searched for a more reliable filament material. After testing a variety of substances, they discovered that bamboo fiber performed better as a filament than carbonized cotton threads. Edison sent agents to Japan, South America, and Florida to locate different bamboo varieties for testing. By December 1880, Edison had decided to use Japanese bamboo in his filaments.

The lamp factory, equipped with electric circular saws to cut bamboo filaments and gas-powered glass-blowing machines, produced its first batch of lamps for laboratory testing in September. In November, Edison organized the Edison Lamp Co. to manage the factory. With a capacity of 1,200 lamps per day, commercial production began in the spring of 1881.

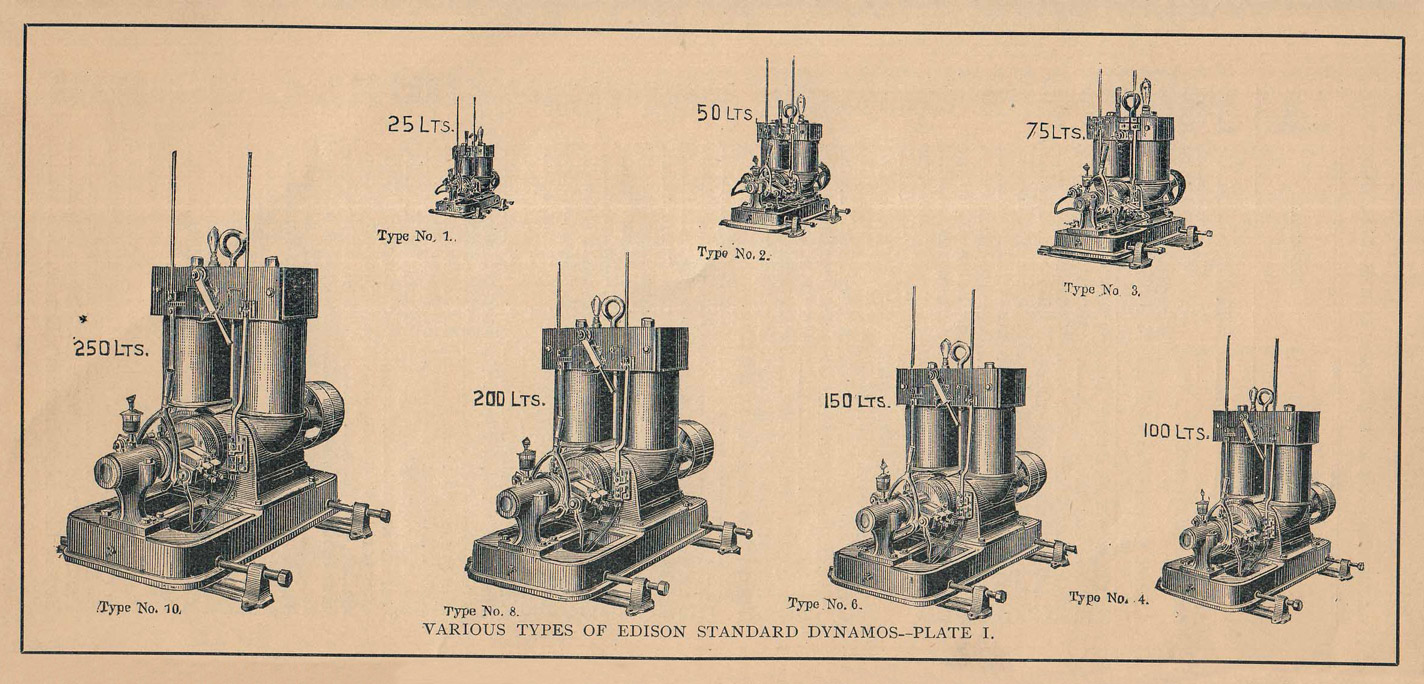

Edison dynamos, or generators, rated for different light capacities. Purchasers of isolated lighting plants could choose the dynamo suited to their needs.

On March 4, 1881, Edison organized the Electric Tube Co. to manufacture underground conductors for central stations. That same month Edison and Batchelor created the Edison Machine Works to produce dynamos and other large equipment for the Edison lighting system, and in April, Edison associates Sigmund Bergmann and Edward Johnson established Bergmann & Co. to produce electric light fixtures.

Edison had identified centrally produced electricity as a key marketing strategy of his system. In the October 1880 issue of North American Review, he announced plans for introducing his electric lighting system “in all the great centers of population throughout the U.S.” He described this system for the New York World in November:

From a central depot in each district I shall send out light and power for half a mile. The wire will be laid in pipes. . . . Every 20 feet the pipes will pass through boxes, where connections may be made with houses. The wires will run directly to a meter in each building supplied, and the electricity will be measured just as gas is measured now.

Edison preferred to focus on developing a central station business, but he also offered customers isolated lighting plants—stand-alone systems with their own steam engines and generators. In May 1880, Edison installed his first isolated plant on the S.S. Columbia, a newly constructed steamship owned by Henry Villard’s Oregon and Railway Navigation Co. As the first system operated outside of Menlo Park, it included four generators and 120 lamps. New York lithographers Hinds, Ketcham & Co. installed the first land-based isolated lighting plant in February 1881. The firm printed color graphics and claimed that Edison’s light was better for matching colors than any other form of artificial illumination. In April, the Edison Electric Light Co. created the Bureau of Isolated Lighting to manage the isolated plant business. The bureau became an independent firm—called the Edison Co. for Isolated Lighting—in November 1881.

Edison “jumbo” dynamo, or generator, at the 1881 Paris Electrical Exhibition. The dynamo weighed thirty tons and generated enough electricity to light 700 lamps.

By the spring of 1883, Edison had sold 330 isolated systems, which provided more than 64,000 lamps. Isolated plants were expensive and required an experienced technician to operate and maintain, so typically plants were sold to large commercial and industrial businesses, hotels, and theaters.

The Edison Electric Illuminating Co. of New York was organized on December 17, 1880, to construct and operate central stations in Manhattan. The first district was a one-mile-square area in lower Manhattan, bounded by the East River, Wall Street, and Spruce, Ferry, and Nassau Streets. Edison strategically located this first district to attract the attention of New York’s newspapers and leading financial institutions, generating favorable publicity and the support of bankers who would invest in further development of the electric lighting system.

Edison needed the city of New York’s permission to lay underground conductors, but the city government initially rejected Edison’s request to install 100,000 feet of underground wiring. Favorable action on Edison’s application, however, followed an electric light demonstration at Menlo Park for the New York City Board of Aldermen and an elaborate dinner catered by Delmonico’s restaurant on December 20, 1880. Edison began laying underground conductors in the spring of 1881. To supervise construction of the system, Edison spent much of 1881 in New York. In March he moved his residence to New York and opened an office for his electric light companies at 65 Fifth Avenue.

Work crews completed installing the underground conductors in the summer of 1882. For the central station, the company purchased a building at 255-257 Pearl Street. To handle the weight of all the equipment, the foundation, walls, and floors of the building were fortified. Two eight-foot-tall smokestacks were constructed, along with a steam-operated conveyor system for loading coal into and removing ash from the boilers. The station had four large boilers and six twenty-seven-ton generators, each capable of producing 100 kilowatts of electricity. The Edison Electric Light Co. estimated that the plant would consume five tons of coal and 11,500 gallons of water each day. Construction costs for the station, including real estate, generating equipment, fixtures, and underground wires, reached $300,000 ($6,810,000 today).

The Pearl Street station began supplying electricity to 368 buildings wired for 8,117 lamps on September 4, 1882. On the next day, the New York Herald reported, “In stores and business places throughout the lower quarter of the city there was a strange glow last night. The dim flicker of gas, often subdued and debilitated by grim and uncleanly globes, was supplanted by a steady glare, bright and mellow.”

By April 1884 the Pearl Street station was servicing 500 buildings, wired for 15,000 lamps. As the Edison Electric Light Co. announced in its bulletin that month, “The demand for the light far exceeds the supply, and the station is now being enlarged.” Because operating expenses were higher than its income, the station lost money in 1882 and 1883, but made its first profit in 1884. The station operated until a fire on the morning of January 2, 1890, destroyed all but one of its dynamos. A rebuilt station continued operating until 1895, when it was decommissioned.

Edison at the dedication of a plaque on the site of the Pearl Street central station, New York City, October 1919.

EDISON DID NOT CONFINE his electric lighting business to the United States. As early as December 1878, he had assigned the rights to his British electric light patents to J. P. Morgan’s banking firm, Drexel, Morgan & Co. During the early 1880s, several companies were organized to promote the electric light in Europe, South America, and Asia. The Edison Electric Light Co. of Havana was established in June 1881. Edison’s Indian & Colonial Electric Light Co., organized on June 13, 1881, controlled Edison’s electric lighting patents in Australia and other British colonies. Buenos Aires received an electric light plant in August 1882. In May 1883, the Argentine Edison Electric Light Co. was organized.

Europe, however, was the focus of Edison’s international electric lighting business. Edison sent Charles Batchelor to Paris in July 1881 to supervise the installation of an electric light display for the Exposition Internationale de l’Électricité. Late-nineteenth-century industrial exhibitions were important for introducing new technologies, and for Europeans and Americans, attendance at an exhibition gave them their first glimpse of new inventions, like the telephone, phonograph, and electric light. Exhibitions also allowed potential customers to compare competing technologies. Batchelor’s assistant, Otto Moses, described the Paris exposition’s opening: “With the greatest of pleasure I chronicle the complete success of our illumination. Last night for the first time we ran the entire capacity and I assure I never saw a more beautiful sight.” French prime minister Léon Gambetta and King Kalakaua of Hawaii, among other prominent dignitaries, visited the Edison display.

Batchelor remained in Paris after the exposition to organize companies to manufacture and promote the electric light in France. Edison and his business associates were concerned that the interest generated by the Paris Exposition would encourage European competitors to infringe his patents. In February 1882 three electric light companies were organized in France: the Société Industrielle et Commerciale to manufacture electric lamps, the Société Électrique Edison to promote central stations in France, and the Compagnie Continentale Edison to license Edison electric light companies throughout Europe. One of these companies, the Deutsche Edison Gesellschaft, organized in March of 1883, operated a central station in Berlin.

Edison sent Edward H. Johnson to London in the fall of 1881 to exhibit the electric light at the Crystal Palace Exhibition and to open a central station. Johnson demonstrated the lamp at a meeting of the Royal Society of Arts in December. According to Johnson, “The Edison light made a successful debut in London . . . we had a crowded house and the lights were very steady and uniform.”

The successful display of Edison’s electric lighting system at the Crystal Palace Exhibition in 1882 attracted favorable attention from English nobility and leading scientists (Getty Images: Achille-Louis Martinet/The Bridgeman Art Library)

At the 1882 Crystal Palace Exhibition, Johnson lighted two large rooms—the Entertainment Court and the Concert Room—as well as the avenue leading from the Crystal Palace to the exhibition railroad station. The concert room had 235 lamps, with eighty lamps suspended from a large chandelier. The Prince of Wales attended a preview on January 18, 1882. Johnson amazed the prince and 150 other dignitaries by submerging a lamp underwater and smashing another lamp wrapped in a cloth in order to prove that a broken lamp posed no fire danger.

Johnson thought that Londoners, who “live and breathe (foul gas-polluted air) in the daytime made artificially nighttime by the London fog,” would appreciate Edison’s clear, bright light. Johnson located the central station on Holborn Viaduct, a bridge built in the 1860s in the city of London connecting Holborn with Newgate Street. It was an ideal location for the central station because it was close to newspaper offices on Fleet Street, the General Post Office, two railroad stations, two hotels, and a church.

A subway ran under the viaduct, and gas and water mains serving the buildings on the viaduct were located in the tunnels. This allowed Johnson’s workers to install power lines without opening the streets, which required the permission of Parliament. As a result, Johnson could supply electricity to the buildings without moving even a shovelful of earth. The station—the world’s first Edison electric light central station—opened on April 13, 1882, with a capacity of 2,200 lamps.

The Holborn Viaduct central station served a half-mile-long district from Holborn Circus and Newgate Street to the General Post Office, powering nearly 1,000 lamps on four circuits for street lighting, restaurants, hotels, and shops. (Stengel & Co.)

By 1883 Edison had established a group of companies to manufacture and market his electric lighting system, but the parent company, the Edison Electric Light Co., lacked the capital to expand the business. On May 1, 1883, Edison invested his own money to organize the Thomas A. Edison Central Station Construction Dept. From May 1883 to September 1884, when it merged with the Edison Co. for Isolated Lighting, the Construction Dept. planned and built thirteen electric light central stations in smaller towns in Massachusetts, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York. In those towns, local investors organized an electric illuminating company and then paid Edison’s Construction Dept. to design and install the electric lighting system. This involved canvassers conducting street-by-street, house-by-house surveys to collect detailed information about the number and types of customers. With this information, Edison’s staff determined the best location for the town’s central station and laid out the distribution system. Because Edison’s direct current system could serve an area of only one square mile, the canvassers had to identify the right balance between residential and commercial customers in order for the local illuminating company to make a profit. The Edison Construction Dept. installed the generating plant and briefly operated the system before turning it over to the local company.

LEFT: Edison attempted to keep the cost of his electric light competitive with gas lighting, but the initial expense was high. Lamps were priced at $1 each ($22.70 today), but a 750-light isolated plant could cost as much as $12,000 ($272,000 today). RIGHT: Bergmann & Co. manufactured Edison electric light fixtures in different styles and finishes. The price of these fixtures ranged from $1.75 to $38.50 ($39.50 to $874 today).

By early 1884 Edison had resolved the major technological challenges of designing an electric lighting system, but he continued to face a number of technical and commercial problems. In the laboratory he spent much of his time improving the performance of lamp filaments and lowering production costs. This was not pioneering research, but it was essential to the viability of his electric lighting business.

In early February 1884 Thomas and Mary left New York for a two-month vacation in Florida. When they returned at the end of March, he confronted financial problems that threatened the expansion of his electric lighting business and eventually led to the reorganization of the Edison Electric Light Co. Edison had supported the Central Station Construction Dept. with $11,000 of his own money—funds he expected the Electric Light Co. to reimburse. The directors of the company, however, were never enthusiastic about being involved in the central station business, preferring to rely on the sale of patent rights to generate revenue. The company also lacked funds to repay Edison because of a shortage of capital in the nation’s banking system, and the board of directors attempted to bring Edison’s spending under control. Under these circumstances, Edison decided to close the Construction Dept. but instead reached an agreement with the Electric Light Co. to merge the department with the Edison Co. for Isolated Lighting on September 1, 1884.

In October Edison waged a proxy fight to replace the board of the Edison Electric Light Co. with directors who were more sympathetic to his business philosophy. As Edison told the New York Sun, “We want a Board with less law and more business. . . . I have given a perfect system, and I want to see it sold. . . . I don’t want to see my work killed for want of proper pushing.” In a compromise reached at the end of the month, Electric Light Co. president Sherburne Eaton and board member Grosvenor Lowrey resigned. They were replaced by Eugene Crowell, who became president, and Edison’s former Menlo Park associate Edward Johnson, who became vice president.

How do you keep electric power plants productive during the day, when no one needs electric lights? Edison answered this question at Menlo Park by designing motors to power elevators, industrial machinery, and electric railroads.

Edison first thought of electric railroads in the summer of 1878, as he traveled through Iowa on the way to California. Seeing Iowa’s vast cornfields, Edison believed that short electric railroads could ship grain to the state’s main railroad lines “and thus extend the radius of economic grain production.”

In the winter of 1879, Edison asked Grosvenor Lowrey if the Edison Electric Light Co. would invest in an experimental railroad at Menlo Park. Lowrey told Edison to forget the idea and focus on the electric light, but Edison continued to work on the problem and, by May 1879, had produced a set of drawings for an electric locomotive and track. Edison later explained, “I determined to construct the railway the first chance I could get the money to do so.”

Edison found the money in February 1880 and spent $15,000 ($340,000 today) building a three-fourths-of-a-mile-long track along sharp curves and steep grades next to the Menlo Park laboratory. The locomotive motor—a modified dynamo—had a capacity of thirty-five horsepower and could reach a speed of forty-two miles per hour. Power was supplied to the rails by two steam-driven dynamos in the laboratory’s engine room. Workers completed the railroad in May 1880 and carried lab workers and visitors back and forth throughout the summer.

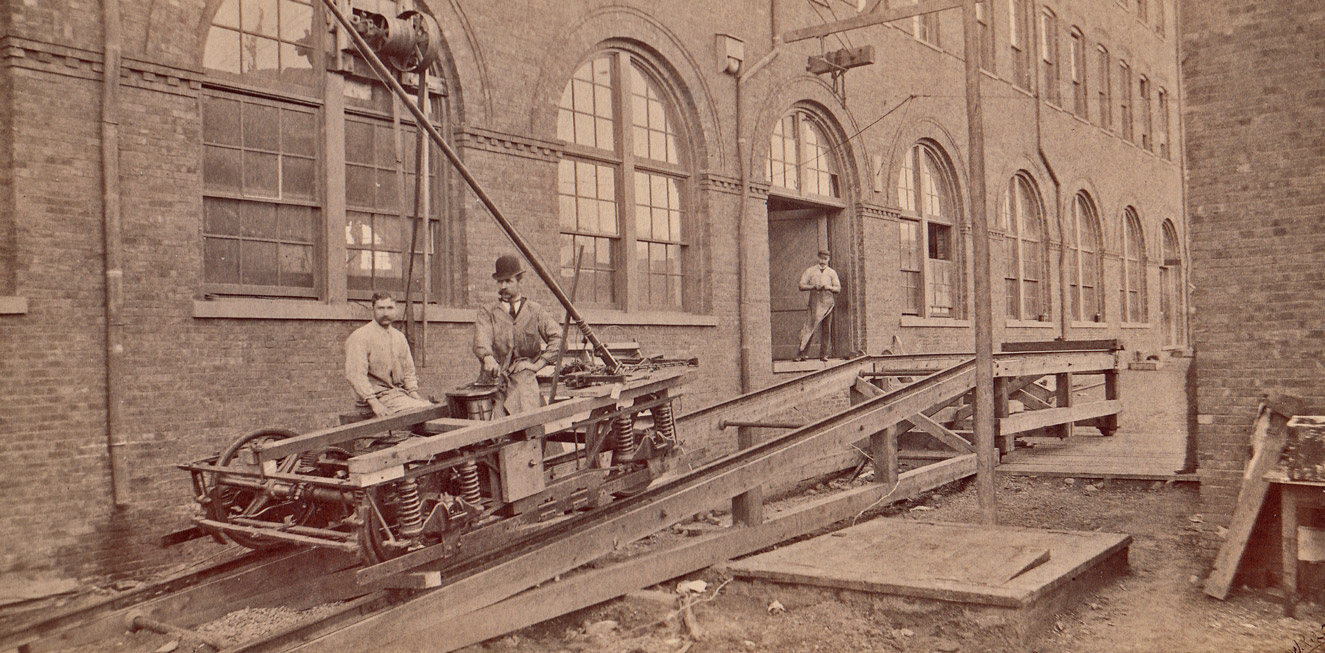

Edison began planning a longer railroad in August 1881. On September 14, Henry Villard, an Edison Electric Light Co. director who had recently assumed control of the Northern Pacific Railroad, agreed to finance construction of a new two-and-a-half–mile track near the Menlo Park laboratory, equipped with three cars and two locomotives—one for passengers, the other for freight. In November Samuel Insull reported that Edison

is building a passenger locomotive which will be fitted up in splendid style and which will have a maximum capacity of one hundred miles an hour. Whether it will ever run at this rate when finished will very much depend upon the courage of the driver. I think it would be a very good speculation to insure the lives of the passengers the first time Mr. Edison determines to run at this speed.

The two-and-a-half-mile–long railroad was completed by April of 1882. In May, Edison reported that he had “one locomotive capable of pulling four cars each containing thirty passengers at 20 miles per hour . . . the whole thing works splendidly.”

Henry Villard, who needed funds to complete construction of the Northern Pacific Railroad, withdrew his support of the electric railroad experiments in December 1881, and Edison continued the research at his own expense throughout 1882. The lack of capital and the demands of dealing with his other electric lighting businesses, however, prevented Edison from organizing a company to market the electric railroad. In April 1883, he assigned his electric railroad patents to the Electric Railway Co. of the United States, to be managed by rival electric traction inventor Stephen D. Field.

TOP: John and Fred Ott test an electric railroad motor outside the heavy machine shop of the West Orange lab in the early 1890s. BOTTOM: Charles Batchelor at the controls of the Edison electric locomotive. Edison’s daughter Marion remembered, “I was always very happy when riding on his electric railway.” (Mondadori Portfolio)