6

“IT IS AN EASY MATTER TO GET SOME MEN TO . . . PRODUCE GOODS, BUT IT REQUIRES A CONSIDERABLY HIGHER TYPE OF MAN TO SUCCESSFULLY SELL THE GOODS.”

AT MENLO PARK Edison unsuccessfully attempted to turn the tinfoil phonograph from a scientific curiosity into a commercial product; at West Orange he succeeded. In the late nineteenth century, Americans began producing and consuming a steady stream of mass-marketed goods. Edison’s efforts to design, manufacture, and market phonographs at West Orange from 1887 to 1929 were a part of this market transformation.

Mass consumer marketing in the late nineteenth century was made possible by several changes in the way the economy manufactured, sold, and consumed products. New manufacturing techniques allowed companies to increase production, while railroads and the telegraph enabled local businesses to expand their operations into national markets. To promote their products, manufacturers adopted new marketing strategies, including branding and mass-circulation advertising. Producing goods in high volume and selling them at low unit prices—a key mass-marketing strategy—made products more affordable to consumers.

At the same time, rising living standards and changing attitudes about spending and leisure encouraged consumption. Cultural values emphasizing leisure and immediate gratification replaced an older ethic that stressed hard work and self-sacrifice. As a result, late-nineteenth-century Americans embraced a variety of new leisure activities and began purchasing manufactured products that were previously made in the home, like soap and clothing. The American household shifted from a center of production to one of consumption.

At first, Edison viewed the phonograph as an office dictating machine, believing that there would be high demand for dictating machines, especially from businesses in areas lacking access to trained stenographers. The steady increase in the value of office equipment production, from $3.6 million in 1879 to $8.2 million in 1889 (from $83.7 to $207 million today), suggested that he was correct. In October 1878, Edison spoke about office workers dictating up to 4,000 words on a tinfoil phonograph. When he resumed phonograph research in October 1886, shortly before beginning construction of the West Orange laboratory, an experimenter noted Edison’s plan to design “a small compact instrument, suitable for office use.”

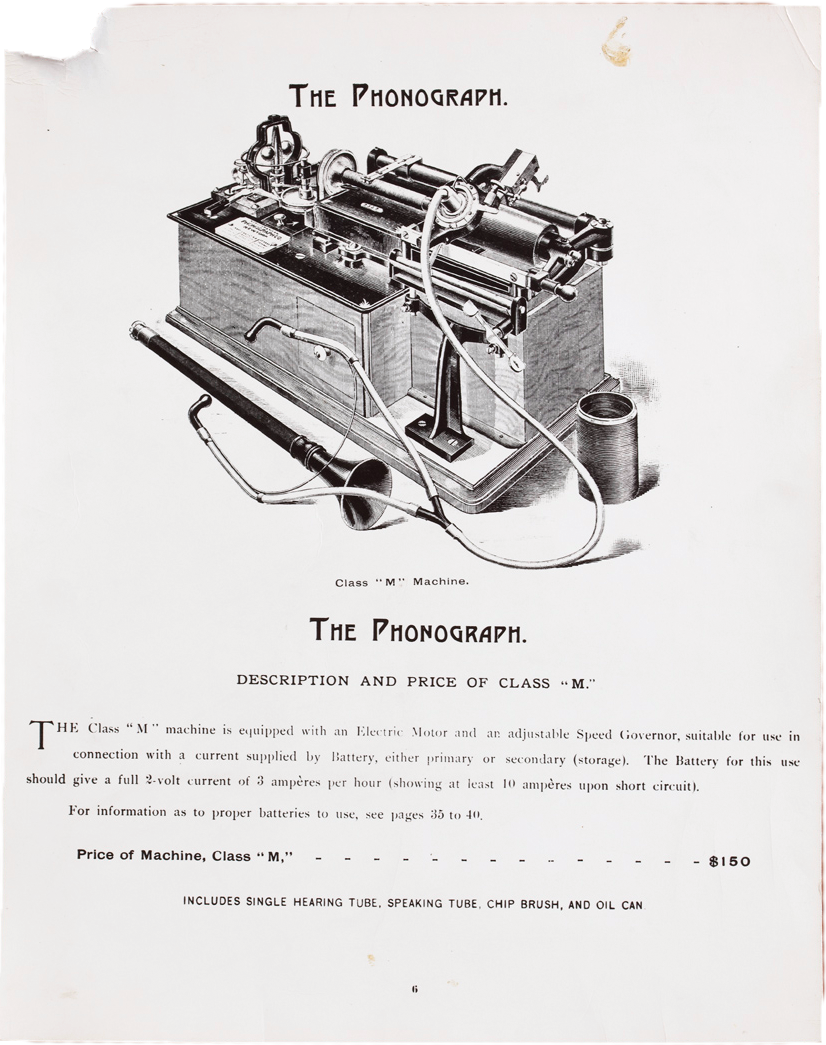

In the fall of 1887 Edison completed the design of his “improved” phonograph. Unlike the hand-cranked tinfoil phonograph, this model was a battery-operated machine with a removable wax cylinder, a recorder/reproducer assembly, a cutting tool for shaving wax cylinders, and a stop/start control. The improved phonograph was significantly better than the tinfoil machine, but it was more of a prototype than a commercial product.

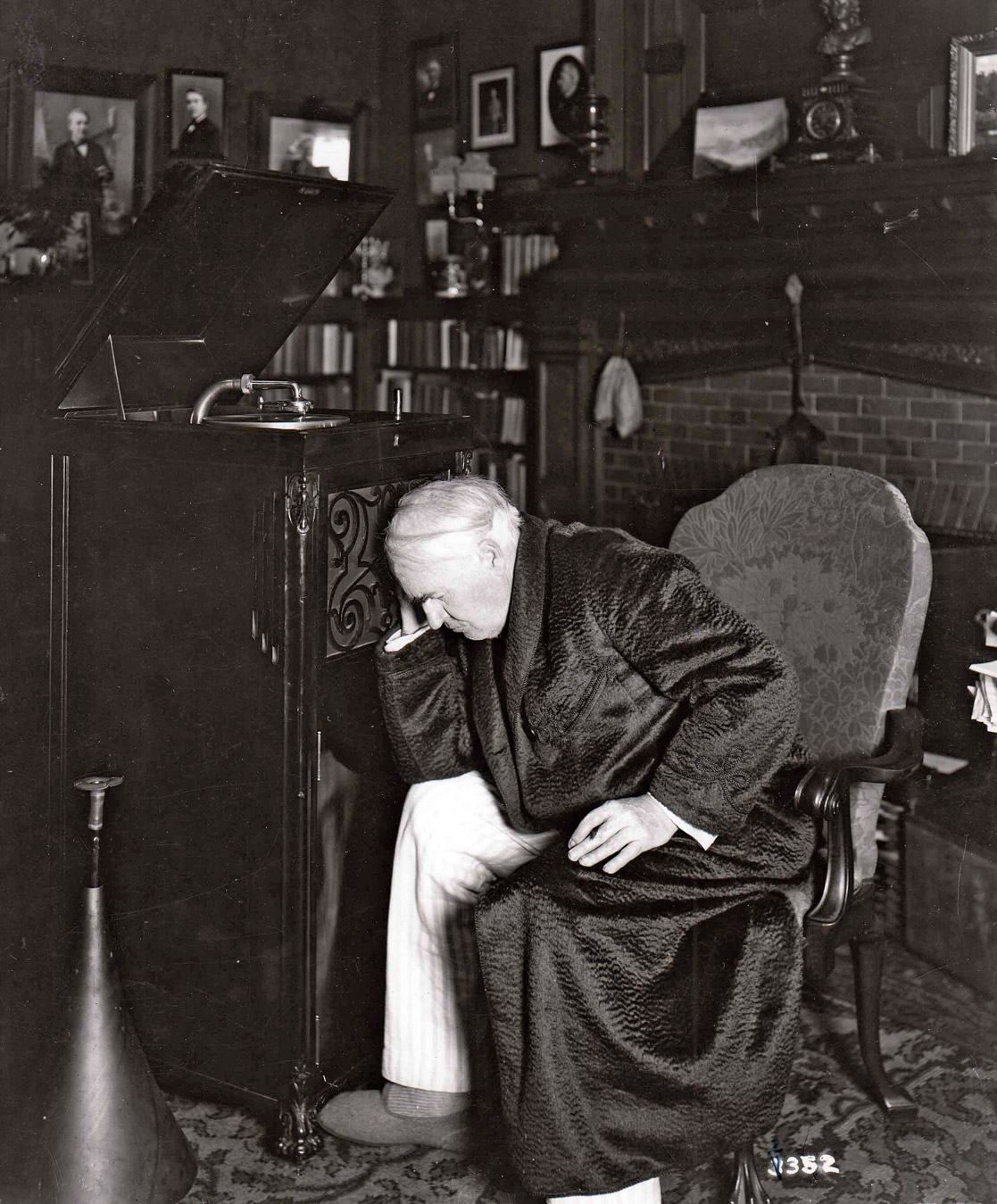

A pajama-clad Edison listening to a disc phonograph record at Glenmont, September 1912.

Edison battery-powered phonographs in the early 1890s included features that allowed office workers to record dictation.

Edison and his staff continued phonograph research into 1888. Edison worked on mechanical features, while Arthur Kennelly focused on the electric motor and battery. Jonas Aylsworth, a chemist hired in October 1887, developed wax cylinder compounds. He conducted more than 700 experiments on waxes, soaps, and fatty acids to produce a cylinder soft enough to take a recording yet durable enough to withstand repeated reproduction. A. Theo. Wangemann experimented on recording techniques, and Franz Shulze-Berge developed record duplication methods. On April 30, 1888, Edison organized the Edison Phonograph Works, and in June 1888 he unveiled a modified version of the new machine, known as the “perfected” phonograph.

While Edison had outsourced phonograph production at Menlo Park, he maintained control of phonograph manufacturing at West Orange. He planned to make phonographs using the “American System of Manufactures,” a production process introduced in the early nineteenth century to manufacture firearms. Instead of skilled craftsmen making individual parts, unskilled laborers assembled phonographs with prefabricated parts. This system lowered production costs, increased productivity, and resulted in uniform, standard products. Lower production expenses enhanced Edison’s competitiveness by allowing him to decrease costs to consumers. Keeping phonograph production close to the laboratory also allowed Edison and his experimenters to rapidly implement design changes and quickly introduce improvements in manufacturing techniques. Thus, phonograph production increased from ten machines a day in the fall of 1888 to fifty by the spring of 1889.

Edison’s talking doll, developed at West Orange during the late 1880s, was part of his strategy of quickly designing new products in the laboratory, manufacturing and selling them on a mass scale, and returning the profits to the lab to support new research.

In October 1887, Edison signed a contract with William Jacques, an employee of the Bell Telephone Co. in Boston, and his associate Lowell Briggs to market talking dolls. Jacques and Briggs, the inventors of a doll phonograph mechanism, then organized the Edison Phonograph Toy Manufacturing Co. Edison was dissatisfied with their phonograph mechanism design, however, and asked Charles Batchelor to improve it.

In February 1888, the laboratory designed a sound reproducing mechanism small enough to fit inside a doll, and on March 6, 1888, Batchelor wrote in his notebook, “Made a small phonograph for dolls, etc. with an automatic return motion so that you simply turn always in one direction and it says the same thing over and over again.”

A rough sketch shows that experimenters considered placing the phonograph inside the doll’s head, with the speaker horn placed near the doll’s mouth and a pull string at the back of the head, but in the final design they mounted the mechanism inside the doll’s torso.

In this November 1889 drawing, experimenter Charles Wurth envisioned a phonograph mechanism in the talking doll’s head. Ultimately, Edison put the mechanism in the doll’s body.

In the fall of 1888, newspapers began publishing stories about Edison’s doll. As the New York Sun reported on November 22, “Children all over the world will before long have reason to bless the name of Thomas Edison for that wizard has just perfected a toy the like of which was never dreamed of by them even on Christmas Eve.” Edison, the Sun announced, would begin manufacturing and shipping dolls in large quantities so that, soon, “children not only in America, but also in Europe, and even in far off Russia will be able to possess dollies that in their owner’s native language can talk to them.” Edison hoped to have the dolls ready for the 1888 Christmas trade, but, as his secretary told the editor of the New York World, “the details of the mechanism have not been satisfactorily arranged.”

Because of design problems and production delays, Edison missed the 1889 Christmas trade and did not begin producing dolls until early 1890. By March 1890, the Edison Phonograph Works, which manufactured the mechanisms and inserted them in doll bodies purchased from Germany, had manufactured 3,000 dolls. Toy dealers began selling the dolls, but, because the mechanisms were delicate and easily damaged, consumers soon began returning them. As one dealer reported, “We are having quite a number of your dolls returned to us. . . . We have had five or six recently sent back some on account of the works being loose inside, and others won’t talk and one party sent one back stating that after using it for an hour it kept growing fainter until finally it could not be understood.” Edison took the talking doll off the market in April 1890.

Edison National Historical Park preserves the earliest surviving talking doll recording. On the recording, produced in 1888, an unknown woman recites the nursery rhyme “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star.” Museum curators found the thin, ring-shaped metal recording in Edison’s library in 1967, but, because it was significantly twisted, it could not be played on sound recording equipment. In 2011, scientists at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory created a digital model of the recording and reproduced the audio with optical scanning technology.

Following Edison’s strategy of rapidly developing new products, the West Orange lab quickly introduced the talking doll, but it failed to meet consumer expectations. (Christopher Bain)

Edison sold the phonograph marketing rights to Jesse Lippincott, a Pittsburgh glass manufacturer who had earlier purchased the rights to the graphophone, a rival talking machine invented at the Washington, D.C., laboratory of Alexander Graham Bell. Lippincott organized the North American Phonograph Co., which licensed subsidiaries in exclusive territories to lease phonographs. By May 1890 there were thirty-two licensed local phonograph companies in the United States. The North American Co. leased phonographs to the local companies for an annual fee of $20 ($510 today). The local companies, in turn, leased phonographs to customers for $40 per year.

Window display for Edison wax cylinder records.

Technical and marketing problems prevented the North American Phonograph Co. from establishing a profitable talking machine business. Changes in temperature and humidity warped and cracked the wax cylinders, making them difficult to remove from the machine. Cylinder records could be shaved for reuse, but the shavings clogged the machine.

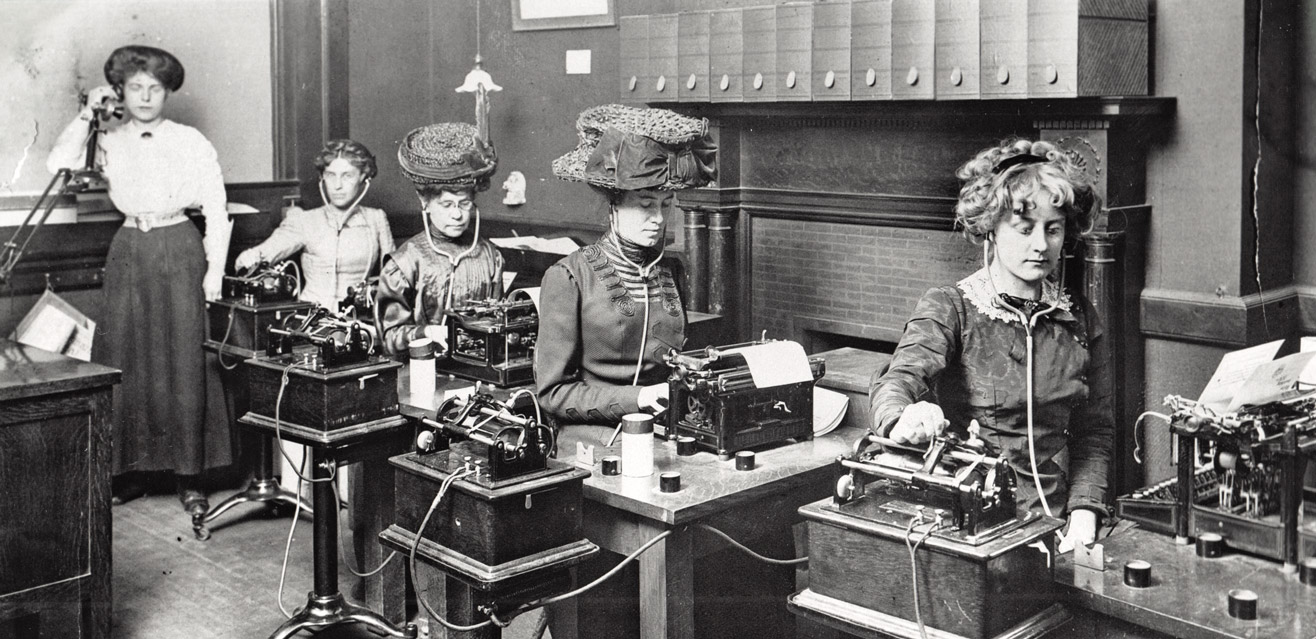

Typists transcribing letters from Edison phonographs. The expansion of office workers in the 1880s and early 1890s convinced Edison that there would be a large market for dictating machines.

Customers also found the phonograph too complicated. One local phonograph company manager complained that office workers did not have the technical skills to operate the machine. Another manager told Edison “that if the entire mechanism could be rearranged, made much lighter and more compact it would be desirable. The present phonograph is much too heavy and is liable to create an impression that it is exceedingly complicated.”

The most serious technical problem concerned the phonograph’s chemical battery. Battery-powered electric motors gave the phonograph cylinder steady and even rotation, but customers had trouble getting the batteries to work properly. One user told Edison’s secretary, “I followed the directions closely and short-circuited the battery about fifteen minutes after it had been set up almost 12 hours. The battery seems to ‘run down’ after it has been running the machines about five minutes and then if the machine is stopped the battery will not start it again without assistance.” As Louis Glass, the general manager of the Pacific Phonograph Co., reported to Edison, “The batteries received with machines do not thus far seem to be altogether satisfactory. A single cell will run some instruments up to 160 revolutions whilst others are barely moved and we cannot get 100 revolutions.” Customers complained about the battery’s high cost and messy maintenance schedule. Phonograph batteries were primary cells, requiring the electrodes and chemical electrolytes to be changed when they were depleted. The Michigan Phonograph Co. tersely telegraphed Edison: “Phonograph batteries worthless.”

AS THE LOCAL PHONOGRAPH COMPANIES struggled to market office dictating machines, the phonograph succeeded as a source of entertainment. In the fall of 1889 Louis Glass invented an attachment that changed the phonograph into a coin-operated machine. On November 23, 1889, Glass’s Pacific Phonograph Co. installed a coin-operated phonograph in San Francisco’s Palais Royal Saloon. This phonograph was equipped with a musical cylinder record and rubber listening tubes for up to four customers. For a nickel, saloon patrons could hear a recorded song, short comedy skit, or dramatic reading. On December 4, a second coin-operated phonograph was installed in the saloon, and a third was delivered on December 10. The company’s fourth machine was installed in the waiting room of the Oakland–San Francisco ferry. By May 1890 the Pacific Co. operated fifteen coin-operated machines throughout San Francisco.

Between November 1890 and January 1891 the phonograph companies installed 704 coin-operated phonographs in saloons, hotels, and railroad stations across the country. These coin-operated amusement phonographs were highly profitable. San Francisco’s first coin-operated machine earned $1,035.25 from November 1889 to May 1890 ($26,400 today). The Missouri Phonograph Co. made $1,500 a month from its forty-eight machines ($38,300 today). The Eastern Pennsylvania Phonograph Co. generated up to $550 per month from its twenty-five machines ($14,000 today). Virginia’s Old Dominion Phonograph Co. reported, “In towns of three, four, five, six hundred and a thousand inhabitants the business pays. We can place the instrument in those little towns and they serve as a plaything, as a variety show. The people in these towns have only the church to go to—they cluster around the machines.”

Despite its success, some phonograph business leaders were reluctant to promote amusement phonographs. North American Phonograph Co. general manager Thomas Lombard urged local companies not to rely on coin-operated machines. “The ‘coin-in-the-slot’ device is calculated to injure the phonograph . . . as it has the appearance of being nothing more than a toy, and no one would comprehend its utility as an aid to businessmen and others for dictation purposes.” Virginia McRae, editor of the talking machine industry trade magazine The Phonogram, predicted that “the phonograph will soon cease to be the toy of the people who frequent saloons and cigar shops.”

LEFT: The popularity of coin-operated phonographs installed in train stations, hotels, and other public places in the early 1890s changed the focus of the industry from business communications to entertainment. RIGHT: Before Edison began selling horns with his spring-driven phonographs in 1896, listeners used rubber tubes and earpieces to hear phonograph records.

The profitable coin-operated amusement phonograph, combined with the commercial failure of the dictating phonograph, changed the focus of the sound recording industry. In June 1893 Edison admitted, “Our experience here shows that a very large number of machines go into private houses for amusement purposes—that such persons do not attempt to record nor desire it for that purpose.”

Because Edison was the North American Co.’s largest creditor (the company had not paid him all of the money it owed for marketing rights or experimental expenses), he forced the company into receivership. Under this procedure, a court-appointed receiver inventoried the company’s assets and liabilities, then auctioned the assets to pay off any creditors. When the receiver sold the company’s assets in early 1896, Edison was the successful bidder and regained control of his phonograph patents.

On January 27, 1896, Edison organized the National Phonograph Co. to market less expensive, spring-driven cylinder machines. In December 1896 he introduced a lightweight spring-powered machine called the Home phonograph, priced initially at $40 and lowered to $30 in 1897 (approximately $1,110 and $839, respectively, today). The development of a reliable spring motor, which provided steady rotation to the phonograph’s cylinder, in the late 1890s helped make the phonograph more attractive to consumers by eliminating the need for complicated batteries.

The Home phonograph was the first in a line of affordable talking machines the National Phonograph Co. marketed to consumers for entertainment purposes. In 1898 Edison unveiled a lighter and less expensive cylinder machine, the Standard, which weighed seventeen pounds and sold for $20 ($560 today). In 1899, he introduced an even lighter and cheaper machine, the Gem, which weighed seven and a half pounds and retailed for $7.50 ($210 today). Lower machine costs allowed National to increase phonograph sales. Machine sales climbed from 1,200 in 1896 to more than 113,000 in 1903. Record sales increased from zero in 1896 to seven and a half million in 1904.

Ads for Edison entertainment phonographs featured colors and images designed to appeal to consumers. This marked an important shift in advertising from the simple black-and-white text and graphics of earlier, business-related Edison products.

The development of less expensive entertainment phonographs in the late 1890s represented an important change in the way consumers used sound recording technology. Edison had eliminated the complicated recording controls found on earlier dictating phonographs, which made them less expensive to produce and less complicated to operate. It also shifted the responsibility of making recordings from consumers to talking machine manufacturers. Consumers could purchase attachments that allowed them to make home recordings, but Edison’s entertainment phonographs were designed mainly for play-back only.

The Edison Fireside phonograph, introduced in July 1909 and encased in a mahogany cabinet, sold for $39 ($995 today). (Christopher Bain)

BY THE EARLY 1900s Edison was a leading manufacturer of entertainment phonographs, but he faced competition from the disc talking machine manufactured by the Victor Talking Machine Co. Organized in 1901 by Camden, New Jersey, machinist Eldridge R. Johnson, the Victor Co. produced the gramophone that was invented by Emile Berliner in the late 1880s. Johnson expanded gramophone sales by designing a tone arm that improved the machine’s acoustic quality. In 1906 he unveiled the Victrola, a disc player with an enclosed speaker horn encased in an attractive wood cabinet.

Victor’s disc records were easier to store than Edison’s cylinder records and could be played longer—from four to seven minutes—allowing the company to record music that would not fit on Edison’s two-minute cylinder records. Further, Victor’s record catalog featured Adelina Patti, Nellie Melba, Enrico Caruso, and other celebrities that it promoted through extensive advertising. These strategies helped Victor increase machine sales from 7,600 gramophones in 1901 to 98,000 in 1907.

Italian tenor Enrico Caruso and the Victrola phonograph, ca. 1910. Recording celebrities like Caruso allowed the Victor Talking Machine Co. to become Edison’s chief competitor in the entertainment phonograph business. (Library of Congress)

Edison’s first response to Victor focused on technology. To compete with Victor’s longer disc record, Edison introduced a four-minute cylinder record called the Amberol in 1908. He also developed a new cylinder machine—the Amberola—which mimicked the Victrola in both name and appearance. The Amberol record improved sales, but it did not challenge Victor. Consequently, Edison’s business managers convinced him to develop a disc machine and record. In 1912, Edison introduced the Diamond Disc phonograph, which featured a diamond-pointed reproducer and a record made out of a material called condensate. That same year he began marketing the Blue Amberol, a celluloid cylinder record that produced a much higher sound quality than earlier cylinders.

In the early twentieth century, the major phonograph companies—Edison, Victor, and Columbia—sold both the talking machines and the records to play on them, so they needed record catalogs that appealed to consumers. Predicting which recording artists and songs would sell, however, was difficult. Victor adopted a successful approach: attract consumers by recording celebrity artists.

Edison refused to use celebrities to promote his records. “We care nothing for the reputation of the artist, singer or instrumentalist,” he wrote in 1912. “All that we desire is that the voice shall be as perfect as possible.” In a November 1911 letter explaining his recording policies, Edison noted, “There are, of course, many people who will buy a distorted, ill-recorded scratchy record if the singer has a great reputation, but there are infinitely more who will buy for the beauty of the record, with fine voices, well instrumented and no scratch.”

Edison based his marketing strategy on the belief that his records and phonographs were technologically superior. Consumers, as a result, would buy his products when they heard their finer sound quality. “It is not our intention to feature artists or sell the records by using the artist’s name,” Edison proclaimed. “We intend to rely entirely upon the tone and high quality of the voice.”

To compete with the Victrola, in 1909 Edison introduced the Amberola, a cylinder phonograph with an enclosed horn priced at $200 ($5,100 today). (Christopher Bain)

In 1911, Edison began listening to the records in his own catalog, and he did not like what he heard. “We use bands when they should be orchestras. We keep instruments in our orchestra which hurt the whole by beating and interfering with the better instruments. We accompany a singer with the other instruments. We accompany a singer with a loud strident blast, when it should be soft and mellow. Our men play out of time, they do not time well.”

Edison also listened to Victor recordings. Overall, he was not impressed, noting in May 1912, “All of the Victor records up to this point are very weak on the table machine three feet away. I can scarcely hear anything but strong notes. The scratch is bad in high priced records & very little in low priced.” He listened to Victor’s recording of “Crucifix,” a duet featuring Enrico Caruso and the famous French opera singer Marcel Journet. Edison liked the tune and thought Caruso’s accompaniment was fair, but he did not think Caruso and Journet were a good combination. He also detected a tremolo, or trembling effect, in their voices that he disliked intensely.

Two additional Victor recordings Edison listened to featured Al Jolson, who later starred in the first feature-length sound motion picture, The Jazz Singer (1927), and became one of the highest-paid entertainers of the 1930s. In regard to Jolson’s “That Haunting Melody,” recorded on December 22, 1911, Edison noted “abnormally sharp voice, metallic—tune not good.” He liked Jolson’s“Snap Your Fingers” even less, simply jotting in his notebook, “Coney Island beer saloon singer—not for us.”

Dissatisfied with his record catalog and armed with definite opinions about the music he liked and disliked, Edison effectively became his company’s music director. He spent hours in the laboratory music room evaluating and selecting the artists and songs the company would record. He filled notebook after notebook with comments and directions for the music room staff.

The Edison Co. produced ten recordings by Russian composer and pianist Sergei Rachmaninoff, but Edison disliked his style (he called him a “pounder”) and refused to release more records. In 1920 Rachmaninoff signed a recording contract with Victor.

Edison liked baritone Francis Rogers, who sang “When the Roses Bloom” and “Little Irish Girl” on January 14, 1915. “Very good, mellow, even voice. You can use him—not for the Irish girl type of song—those of the Roses Bloom type.” He was less confident about Harry Williamson. “This man has bad tremolo most notes—Is not as good as tenors we have. However as public want new singers we might take a few from him if not too expensive.”

Edison listening to mezzo-soprano Helen Davis, accompanied by pianist Victor Young, in the West Orange lab music room, ca. 1926.

Edison approached music selection as a technical problem, not a marketing issue. He deconstructed music like a machine, identifying the parts that he liked and those he disliked—an analogy he made himself, in 1911, when he wrote to his European representative Thomas Graf, “We have a flute that on high notes gives a piercing abnormal sound like machinery that wants oiling.”

Edison expected consumers to appreciate his focus on technical quality, but not everyone cared. Edison’s Omaha, Nebraska, dealer received one complaint: “Let’s have more attention paid to the spirit of a song rather than to make certain that every solitary instrument is surely heard. . . . If the public cared anything for absolute perfect recording where every instrument is clearly heard, the Victor would have been out of business long ago.”

As the foxtrot and other new dance steps became popular in the 1920s, young phonograph users began changing the machine’s speed to increase record tempo. Edison was appalled. In 1925, the seventy-eight-year-old inventor asked one of his engineers to modify the phonograph so that consumers could not change the record speed. “This change of speed is far worse than any loss due to having dance records too slow. They are not too slow they are absolutely right time but young folks of the family want this fast tune. . . . I don’t want it & won’t have it. It does a great injury in more ways than one.”

Dealers complained when the Edison factory removed the phonograph’s speed regulator. “Mr. Edison is still working along the plan of trying to sell the public what he thinks is good for them, rather than what the public wants,” the Kent Piano Co. wrote. “We fail to see why a customer who has just spent his good dollars for a phonograph should be denied the privilege of playing the latest dance records at the speed he has been accustomed.”

Edison’s personal taste in music was one problem; another was the company’s inability to respond quickly to rapidly changing consumer preferences, particularly during the First World War, when more modern forms of music like jazz became popular. Except for letters from individual customers and dealers, the company lacked comprehensive market data to determine what the public wanted. Finding a successful balance between classical and more popular music was also difficult. If the company produced too much classical music, some consumers complained about the lack of popular tunes. If it recorded too much jazz, it would get letters like the one written in 1926 by H. E. McConnell, who complained, “For God’s sake give us more real music like that you have recorded instead of so damned much foolish and unbearable jazz.”

Victor succeeded in part because of its advertising strategy. Edison was not opposed to mass-circulation advertising, even for the phonograph, but he did not spend as much money on ads as his competitors because he believed they could not convey the technical superiority of his products. The goal of his marketing strategy, therefore, was to allow as many consumers as possible to hear his phonographs and records. “Hearing the tone of the Edison,” the company claimed in one ad, “creates the desire to own one and produces a natural comparison in the hearts of everyone hearing the instrument and any needle talking machine they ever hear.”

Edison tested this marketing approach in 1910, when he sent out sales teams with horse-drawn wagons loaded with phonographs and records to canvass customers door-to-door. The seller offered to leave a machine and some records in the home for a free trial, then returned in a few days to complete the sale or remove the phonograph. The wagon operators sent detailed reports to West Orange—information the company used to plan further marketing schemes.

Ads for Edison phonographs and records. Unlike record labels of today, Edison and his sound-recording competitors in the early twentieth century produced both records and record players.

The experience of Roy Matton, a traveler for the Silverstone Talking Machine Co. in St. Louis, is typical. On October 15, 1910, Matton visited forty-one homes. He placed four phonographs on free trial, sold a Fireside machine left on a previous call, and sold no phonographs on the first call. The woman at the second stop “would not consider free trial as she claimed she was afraid the children would make her buy same.” At the next call, Matton reported, “The lady peeped out of the door then slammed it shut.” On his sixth stop, “a German lady” was “out of temper.”

Edison dealers were encouraged to stage showroom demonstrations or recitals for the public. Customers could attend Turn Table Comparisons, where they would compare the Diamond Disc phonograph with competing talking machines. To demonstrate the quality of Edison records, the company sponsored a series of Tone Tests, which featured comparisons between live Edison recording artists and their records played on Edison machines. The goal of the Tone Tests was to demonstrate that Edison records were so precise and realistic that they could not be distinguished from the live performance. Edison recording artist Marie Rappold held one of the first Tone Tests in April 1916 at Carnegie Hall in New York City, and hundreds of similar tests were conducted during the First World War.

"A Dream" Edison Diamond Disc recording, performed by Marie Rappold, November 19, 1917, in New York, NY

“Two Roses” Edison Diamond Disc recording, performed by Marie Rappold, May 1, 1918, in New York, NY

In the 1920s, Edison tested new marketing plans to increase record sales. One plan, launched in September 1922, called for the formation of Edison Home Service Clubs—similar to the Book of the Month Club. Each month, subscribers received twenty records from the Edison catalog. They had two days to listen to the recordings and order the ones they desired from a list before mailing the records to another club member.

The first clubs were organized in Summit and Morristown, New Jersey. Edison based this plan on the belief that he could sell more records through home demonstrations than through mass-circulation advertising. According to company vice president Arthur Walsh, “Edison feels that an actual demonstration of the Edison in the home is the one way to convince people of the Edison’s superior tonal quality.”

The Sub-Dealer Plan involved placing phonographs in barbershops, ice cream parlors, and other stores. The proprietors of these stores were asked to demonstrate the phonograph and send the names of potential buyers to the local Edison dealer. These marketing plans seemed to work when tried on a limited experimental basis, but to be effective against Victor and other competitors, they had to be implemented on a national scale. Edison, unfortunately, did not have the resources to organize and manage large-scale canvassing plans.

The West Orange lab music room, as it appears today. Experimenters developed recording techniques here in the 1890s. In the early twentieth century, Edison used this room to evaluate music and artists for his record catalog. (Christopher Bain)

Edison’s dealers complained about the lack of advertising. In July 1923, C. A. Lloyd wrote the company, “It has been a long time since we have seen an Edison advertisement in any of our national periodicals that I have forgotten what they look like. . . . There is no danger of anyone forgetting what a Victor advertisement looked like or a Brunswick or a Columbia advertisement for the reason that you can scarcely pick up any of our best magazines but the very beautiful, colored, artistic advertisements of these companies stare you in the face.” The company’s response summarized Edison’s view of advertising: “It is his belief and he has proved that Edison phonographs placed in the homes for demonstration sell to a very great extent. Mr. Edison argues that the superior tonal quality of the Edison when heard far outweighs the printed advertising of our strongest competitor.”

LEFT: A truckload of Edison disc phonographs en route to Rooney & Co., Brooklyn, New York. Edison relied on a national network of wholesalers and retailers to market his phonographs. RIGHT: In 1910, Edison dealers experiemented with horse-drawn wagons to deliver phonographs and records for free home trials.

DURING THE EARLY 1920s, phonograph manufacturers faced competition from radio. The first commercial radio station, Pittsburgh’s KDKA, began broadcasting in 1920. By 1922 there were thirty commercial radio stations in the United States. This number climbed to 556 in 1923. Hobbyists with a little knowledge and some radio parts could cobble together their own receivers, but manufacturers began producing radios under the patents of the Radio Corporation of America (RCA). Radio production increased from 100,000 sets in 1922 to 500,000 in 1923. By that year, 400,000 American households had radios.

Consumers began trading in their phonographs for radios, and a number of phonograph dealers began selling radios to regain lost business. Unlike Victor and other phonograph producers, who began manufacturing combination radio-phonograph sets, Edison refused to enter the radio business. He did not oppose radio—in time, he believed it would become an important source of news and information—but because the medium distorted the sound of his recordings, he did not believe it would be a popular source of entertainment. Edison also did not think the radio business would be profitable for his phonograph dealers because the field of licensed radio manufacturers was crowded, and any profits dealers made on radio sales would be eroded by service and repair calls.

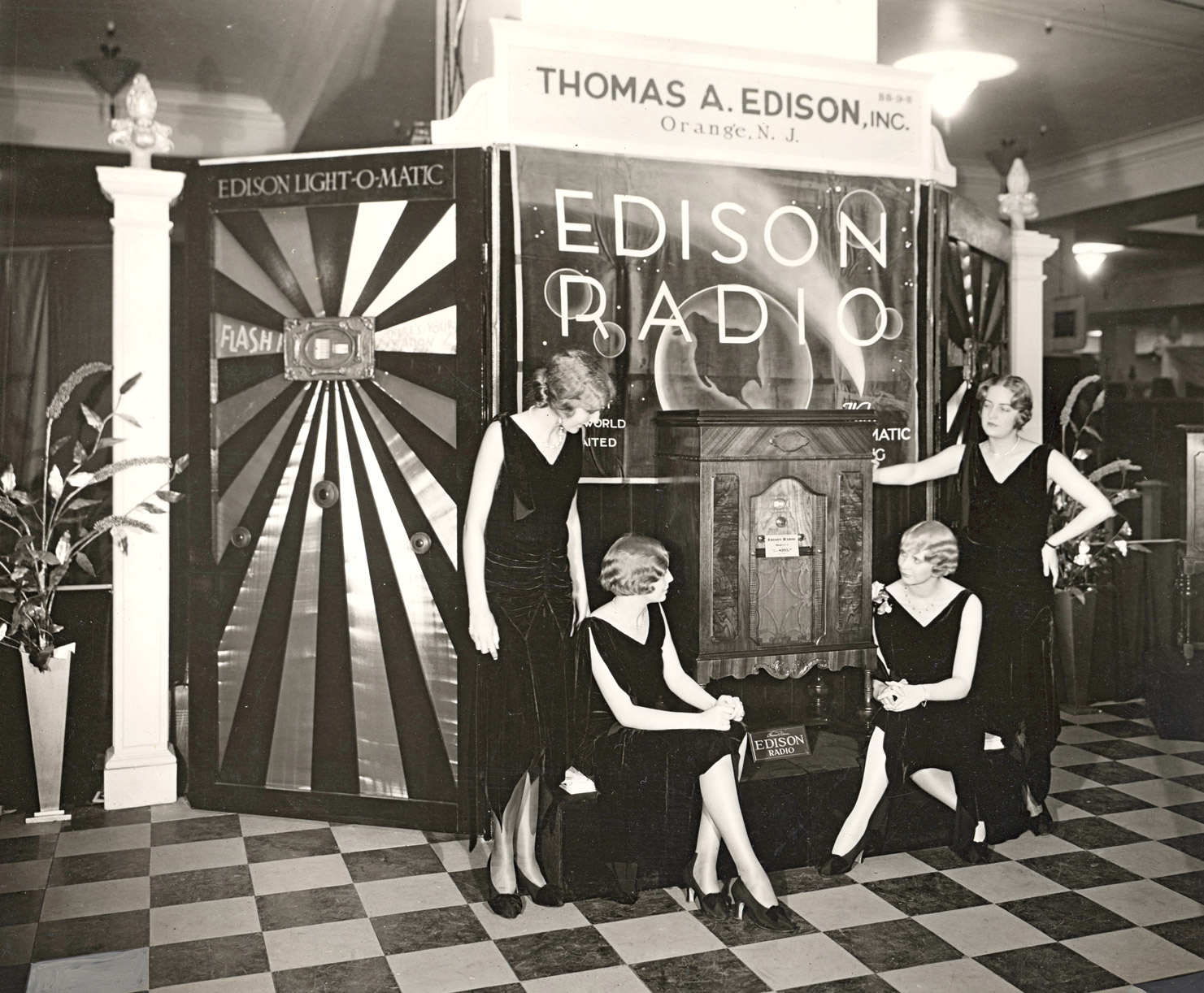

Edison exhibit at the Radio World’s Fair, September 1930, Madison Square Garden, New York City.

In 1928, the company overcame Edison’s opposition to radio and purchased the Newark, New Jersey–based Splitdorf Radio Co., which had a license to manufacture radios under RCA’s patents. Edison’s youngest son, Theodore, took charge of the design of an Edison combination radio-phonograph, but it was too late to save the phonograph business. As Edison predicted, the radio business was not sustainable in the late 1920s; there were too many radio manufacturers who began to cut prices to increase sales. The Edison Co. could not compete in this market.

Edison never regained his early leadership in the phonograph industry. In 1919 he produced 7.2 percent of the phonographs and 11.3 percent of the records manufactured in the United States. By the mid-1920s he controlled 2 percent of the domestic record market. As one Edison dealer lamented in 1926, “Instead of Edison being the most popular machine it is one of the least popular. The Edison, the original, thew Daddy of them all should not take second place for any of them.” After years of steady losses, Edison stopped producing entertainment phonographs and records in the fall of 1929.

In 1903, as the National Phonograph Co. expanded the market for entertainment phonographs, the West Orange laboratory resumed work on an office dictating machine. Unveiled in 1905, the Edison Business Phonograph allowed office workers to dictate letters onto a wax cylinder, which stenographers could then replay to type a paper letter for mailing.

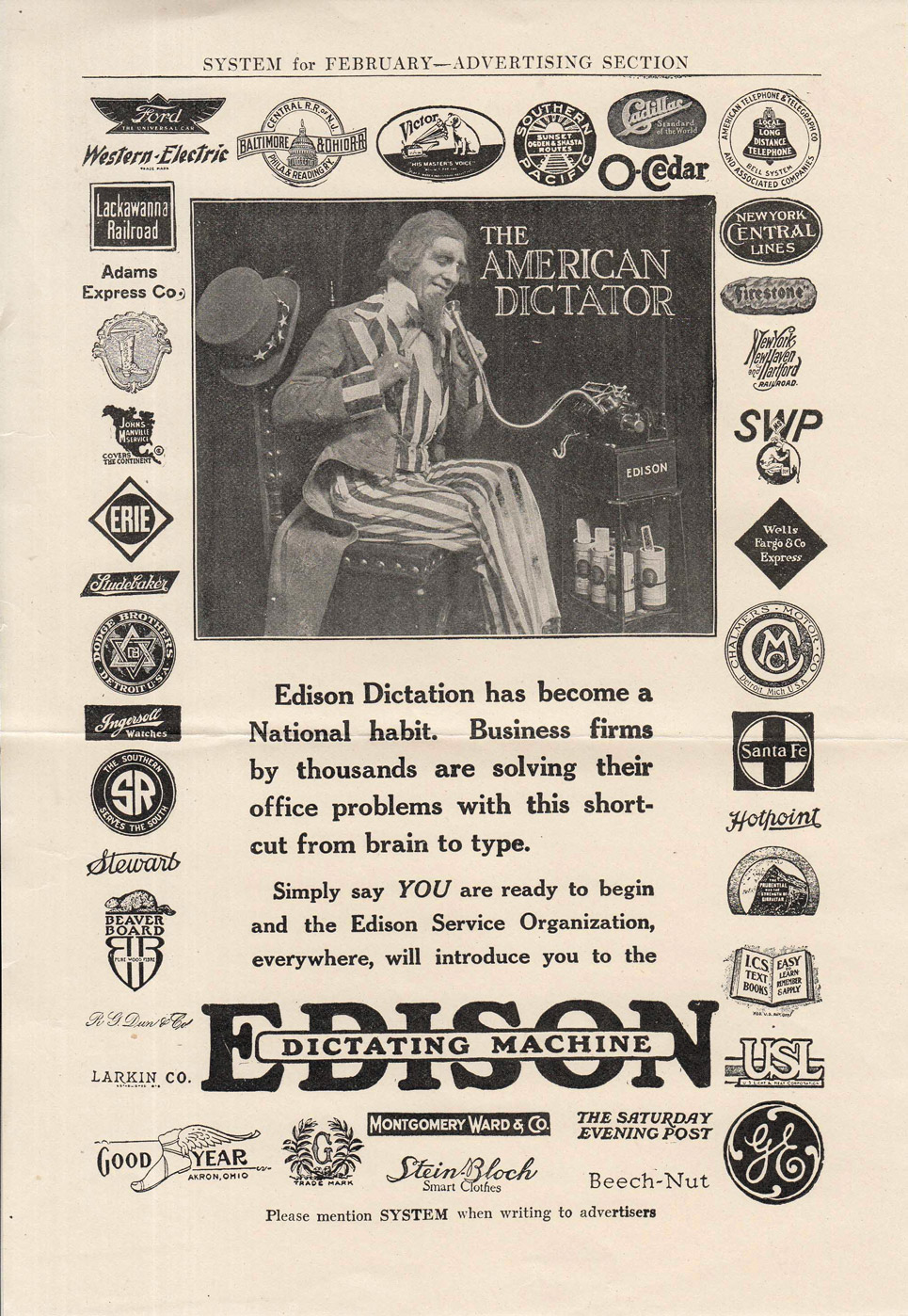

In 1912 the company renamed the business phonograph the “Edison Dictating Machine.” Between 1911 and 1914, the laboratory’s engineering department designed an integrated office dictating system, which included an executive model, a secretarial machine, and a shaving machine to recycle used cylinders. Laboratory engineers also designed the Telescribe, which recorded telephone conversations on a phonograph cylinder. Introduced in 1914, the Telescribe did not perform well in noisy offices. In 1918 it was improved and reintroduced. That same year, Edison’s advertising department renamed the “Edison Dictating Machine” the “Ediphone”—a less cumbersome name that evoked its inventor and more closely resembled the name of a competing machine, the Dictaphone, which was becoming a generic term for office dictating equipment.

During the 1920s, the West Orange laboratory continued to improve the Ediphone’s design, making it simpler, smaller, and less expensive. As Edison claimed in a late 1920s advertising booklet, “I have spared no effort in developing the Ediphone because ambitious people use it and they deserve the best assistance.”

The company continued manufacturing Ediphones after Edison’s death in 1931. In 1951, the company redesigned the Ediphone again and introduced the Edison Voicewriter, producing a portable version the following year. Thomas A. Edison Inc. and its successor, McGraw-Edison, manufactured Voicewriters into the mid-1960s.

Despite Edison’s failure to develop an office dictating machine market in the 1890s, he reintroduced his business phonograph in 1905. (BOTTOM: Christopher Bain)