10

“I DON’T THINK NATURE WOULD BE SO UNKIND AS TO WITHHOLD THE SECRET OF A GOOD STORAGE BATTERY IF A REAL EARNEST HUNT FOR IT IS MADE.”

AT THE TURN OF the twentieth century, the question of whether automobiles would be powered by gasoline, electricity, or steam remained open. Nearly 30 percent of the automobiles produced in the United States in 1900 were electric, and although Edison had predicted that automobiles would replace horses in 1895, he doubted that vehicles would be powered by electricity. Four years later, he changed his mind and began experimenting on storage batteries in the summer of 1899, spending ten years and nearly $2.5 million developing a marketable storage battery for electric vehicles.

There are two types of batteries: storage and primary. Both have positive and negative electrodes immersed in electrolytes—or solutions of acids, alkaline, or salts—and both produce electricity through a chemical reaction between the electrolytes and positive electrodes. The chemical reaction in primary batteries depletes the electrodes and electrolytes, which must be replaced. The reaction in storage batteries is reversible, and the cells can be recharged.

Primary batteries were used in the nineteenth century to power telegraph and telephone systems. They also provided power for electrical experiments in research laboratories. French physicist Gaston Planté invented the first lead-acid storage battery in 1859. In the early 1880s, Edison considered using storage batteries to store electricity during electric light central station off-peak hours, but ultimately decided that they were not practical. When the Boston Herald asked him in 1883 if he saw any hope for the storage battery doing legitimate work, he answered, “None whatever.”

During the 1890s, the design of storage batteries had advanced far enough for electric utilities to start using them for power storage. This application may have convinced Edison that developing a practical storage battery was feasible. The first storage-battery-powered automobile was invented in 1894. However, because the batteries were heavy, difficult to maintain, and prone to corrosion and deterioration, they were not an ideal power source for vehicles. Edison began his storage battery research by outlining its technical requirements. To compete with lead-acid batteries, he would invent an easier-to-maintain, inexpensive, corrosion-resistant, lighter battery that would hold its electrical capacity for a long time.

Initial research focused on identifying materials to replace the electrolytes and electrodes in lead-acid batteries. Edison first considered using sodium hydroxide for the electrolyte, zinc for the positive electrode, and copper oxide for the negative. He soon settled on potassium hydroxide for the electrolyte but continued experimenting on electrode materials. For the negative electrode, the laboratory tested silver oxide, various copper compounds, and cobalt oxide before selecting nickel oxide. Cadmium was an early candidate for the positive electrode, but Edison concluded that it was too expensive and replaced it with iron. To increase the surface area between the electrodes, Edison ground the nickel oxide and iron into fine powders. This required the design of thin, flat pockets of nickel-plated steel, which held the iron and nickel inside the cell. Edison added graphite flakes to the nickel oxide and iron to improve conductivity.

By 1901, after conducting thousands of experiments on different combinations of metals and chemicals, the laboratory had settled on the basic components of the Edison storage battery: iron, nickel oxide, and potassium hydroxide. Identified as the Type E, each battery cell was encased in a steel container twelve inches high, six inches long, and four inches wide.

EDISON APPLIED FOR his first storage battery patents on October 15, 1900. Although the initial storage battery campaign ended by 1909, the West Orange lab continued improving the technology, and Edison submitted additional patent applications for battery modifications and manufacturing techniques. By the time he signed his last battery patent application on October 11, 1927, he had received 140 storage battery patents.

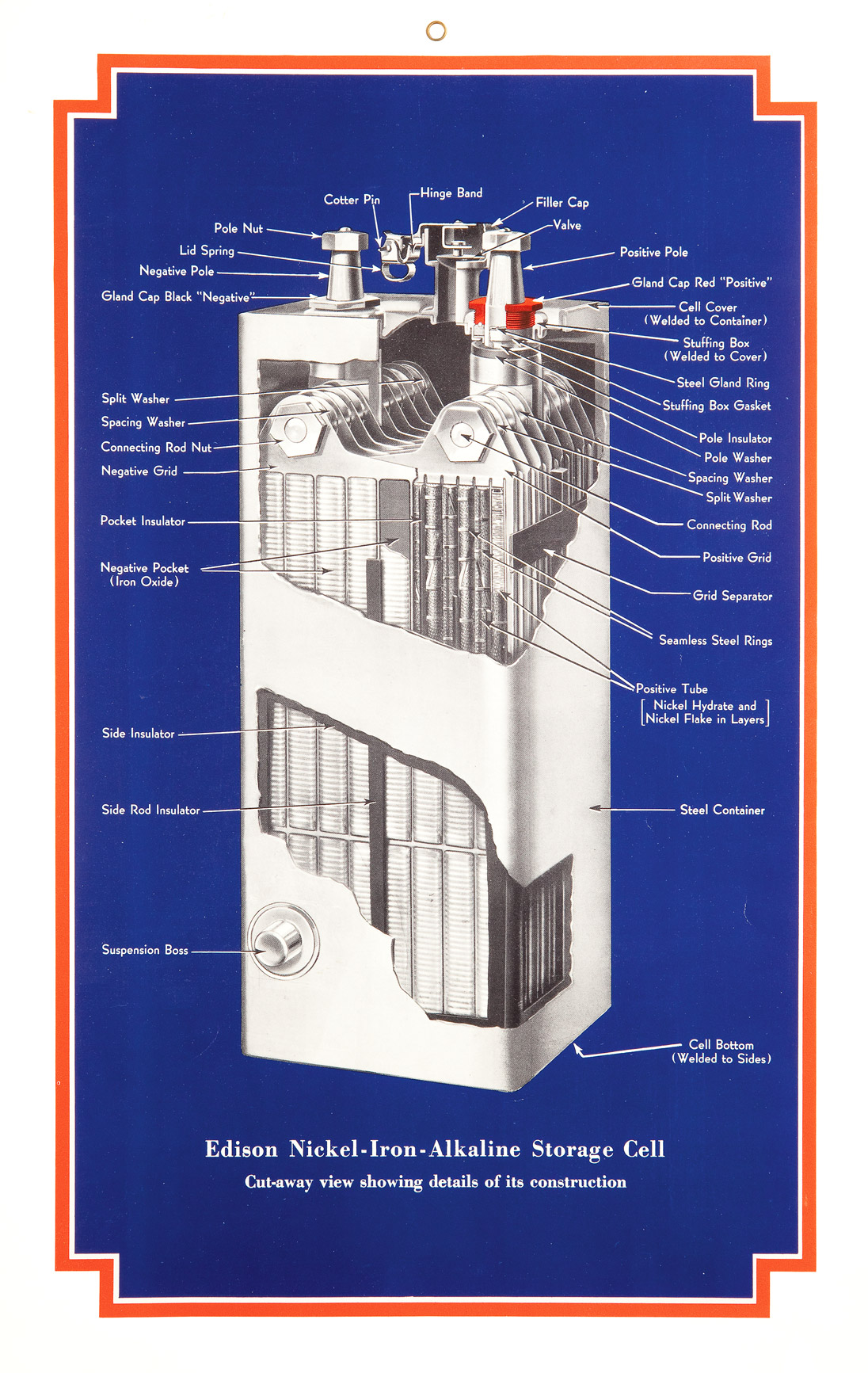

Edison steel alkaline storage battery cell. “Built like a watch, but as rugged as a battleship.” (Christopher Bain)

In May 1901, Edison organized the Edison Storage Battery Co. and established a battery factory in Glen Ridge, New Jersey. In June he sold his U.S. patents to the company for $1 million ($1,000 in cash, $999,000 in stock)—money he used to fund experiments and equip the factory. His marketing plan was simple: He would sell the batteries at discounted prices directly to automobile manufacturers, who were expected to design carriages to accommodate them. Consumers could purchase Edison batteries from the factory, but they were charged the list price: $10, $15, and $25 ($264, $396, and $659, respectively today), depending on the size of the cell.

Edison searched for his own sources of nickel to control raw material costs and to ensure reliable supplies. In September 1901, he sent his brother-in-law John V. Miller and a team of prospectors to locate nickel mines in Ontario’s Sudbury mining district. In July 1902, Edison organized the Mining Exploration Co. of New Jersey, with the financial support of United States Steel Corporation executives, to widen the nickel search to Connecticut and other locations.

Edison began testing the Type E battery in the spring of 1903. In April he wrote to Levi C. Weir, president of the Adams Express Co., “I shall test five automobiles between the factory and Morristown [N.J.] and when the batteries have run 5000 miles each at a high speed and do not show any deterioration and I am entirely satisfied that they are all right, I will then start the factories.” In one of these tests, a light electric runabout equipped with twenty-one cells weighing a total of 322 pounds ran a sixty-two mile course between West Orange and Paterson, New Jersey, over hilly roads, reaching grades of twelve percent. Another test run covered eighty-five miles over muddy, rain-soaked New Jersey roads.

Edison in the West Orange library with his storage battery. Originally designed to power electric vehicles, Edison’s storage battery eventually found wide use in railroad signaling, mining, marine transportation, and other light industrial applications.

Edison subjected the storage battery to punishing road tests because, as he explained to New York banker William D. Sloane in August 1903, “The large carriage builders will go into the electric vehicle business on a considerable scale as soon as they are satisfied the battery is all right.” Road tests not only gave Edison information to improve battery design, but also demonstrated the battery’s performance to automobile manufacturers.

Edison was optimistic that his storage battery would, as the Chicago Record-Herald reported, “revolutionize the automobile business. . . . Mr. Edison himself expects to see his battery take the place of horses on delivery wagons of all kinds in cities, and he believes that in time the principle will be extended to the propulsion of street cars, railroad trains and steamships.” The new battery, Edison wrote to Levi Weir, “will I think solve the problem of vehicle traction. It will have half the weight of those now in use, requires no attention, is fool proof, and has the merit of having none or very slight depreciation.”

By 1904 several auto manufacturers, including the Pope Motor Car Co., Studebaker Brothers Manufacturing Co., the Baker Motor Vehicle Co., and the Electric Vehicle Co. had designed cars for the Edison storage battery. Edison recommended the Studebaker to William Sloane but preferred the Baker electric for women. “The Baker is a very light runabout, weighs 850 to 900 lbs and will go as far as a Studebaker but its generally used by ladies and young girls and its considerably cheaper. My daughter has used one constantly for 2 ½ years.”

The Glen Ridge factory began manufacturing storage batteries in January 1903. Weekly production soon reached 200 cells, and initial battery sales were promising. One Edison Co. official remarked in January 1904, “The storage battery has been on the market since July last. We have had so many orders come to us, it has not been necessary to advertise it.” In July 1904, Edison wrote, “We are getting along all right, we are manufacturing and selling all we can make, our business is now at rate of $300,000 per year.”

A Bailey electric car in the West Orange lab courtyard in 1910, after a 1,000-mile endurance run. To test their durability, Edison subjected his storage batteries to punishing trials.

In November 1904, Edison ordered the factory to stop battery production after he began receiving reports of leaking battery cans and loss of electrical capacity after several charges and discharges. He told Levi Weir, “At present I do not want to sell any more batteries than I am compelled to until I solve the leaking can problem.”

The leaks were caused by chemicals corroding the solder used to seal battery cans. Edison solved the problem by replacing solder with a new welding process to seal the cans. The loss of capacity was a more difficult challenge. Edison noted in October 1904 that “after a long run some cells maintain their original capacity while others lose 30% although all made under the same conditions.”

Cutaway of Edison storage battery cell. Each cell contains two sets of positive and negative plates. The plates support grids of tubes and pockets holding the active materials of nickel hydrate (positive) and iron oxide (negative).

It took Edison and his experimenters several years to identify and resolve this issue. Ultimately, they discovered that the nickel oxide electrodes expanded during the charging process and contracted during discharge, which increased the cell’s internal resistance and lowered capacity. Edison corrected this by designing a round electrode pocket to replace the Type E flat pocket. He improved the conductivity of the pockets by adding layers of nickel flake between the nickel oxide and by designing machinery to compact the layers of nickel under high pressure.

EDISON BEGAN MANUFACTURING the redesigned storage battery, which he named the Type A, in July 1909. In correcting the Type E’s defects, he had improved the battery’s electrical capacity and increased the time a cell could hold its charge. Edison expected a heavy demand for the new battery and began constructing a larger storage battery factory across the street from the West Orange laboratory to replace the Glen Ridge plant.

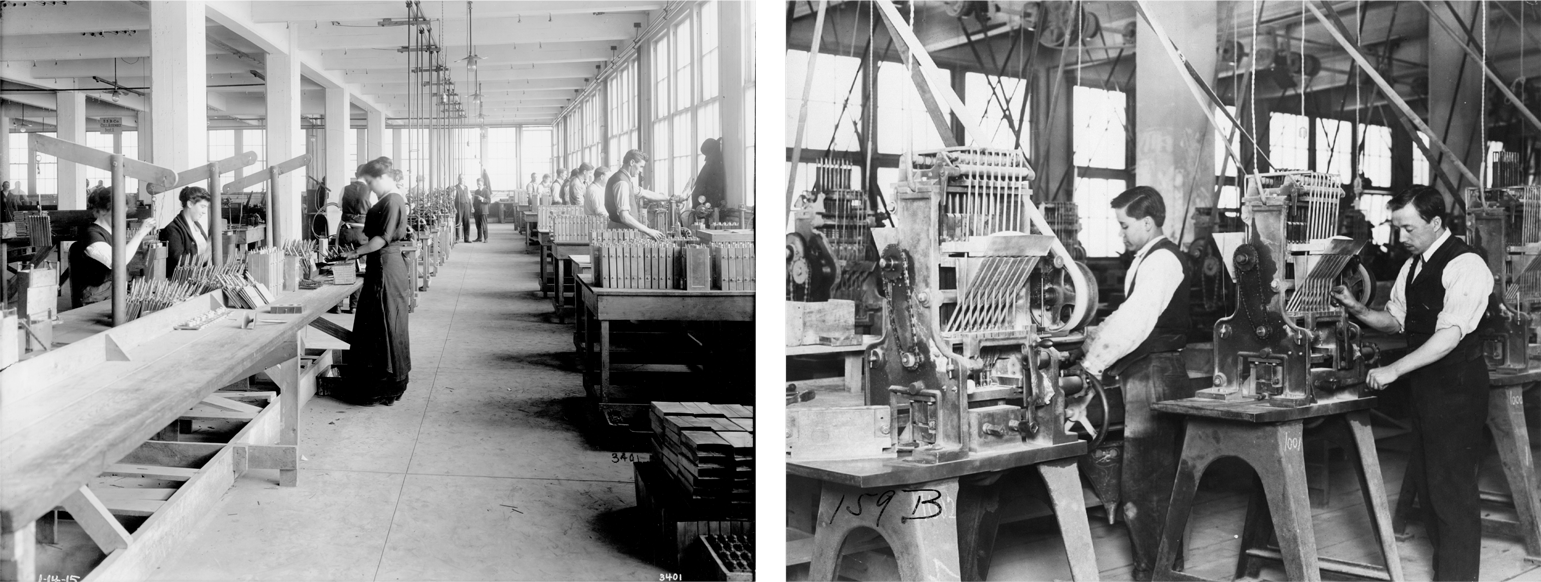

LEFT: Edison storage battery assembling department, West Orange, January 1915. RIGHT: Workers operate tube-loading machines in the West Orange storage battery manufacturing plant. Along with new products, the West Orange lab designed machines to mass-produce them.

By 1910, however, the market for electric pleasure vehicles had changed. In 1908 Henry Ford introduced his low-priced Model T, which made gasoline-powered cars more affordable. Before the invention of electric starters, gasoline engines had to be hand-cranked—an especially difficult task on cold mornings. Consumers appreciated the convenience of starting electric cars, but gasoline-powered cars were faster, were less expensive to operate, and had a wider touring range.

When Edison checked automobile registration records in Trenton, he learned that 98 percent of the electric cars registered in New Jersey from 1899 to 1906 had been abandoned because of the unreliability and expense of lead-acid storage batteries. Electric vehicle owners complained about the length of time it took to recharge batteries and about the low mileage they could travel on a single charge. As William M. Lawrence, the pastor of the North Orange Baptist Church, explained to Edison in June 1910, “If I were asked in a word what is the main difficulty, I would say the uncertainty regarding the length of time the car will go on one charge. Sometimes this year I have not gotten more than eleven miles.” Thomas W. Harvey, a doctor in Orange, New Jersey, complained about his electric car experience:

I put in new batteries about every 2,500 miles. I ran the car about 2,000 miles a year, it cost me about $500 a year, but I had the satisfaction of knowing that only the wealthy can really enjoy life, and I took great comfort from the fact that even if a five thousand dollar limousine did whisk past me at a forty mile gait, when I was laboriously doing four miles an hour, still my ride was costing me so much more than the other fellow’s that I could look down with disdain upon him.

Edison believed his new Type A storage battery would overcome these objections:

The mileage is such with the new battery that man & wife & child can go out all day on one charge, on good roads here 150 miles is being done. They will probably displace the cheap gasoline car as people are finding that the repairs & upkeep of the later are really prohibitive & they seldom last four years. Whereas any lady can run the electric & the up keep as compared to gasoline is a mere nothing.

Automobile owners who preferred electric vehicles, however, tended to purchase the Exide, the lead-acid storage battery manufactured by Edison’s principal competitor, the Electric Storage Battery Co. Although Edison’s battery was more durable and less expensive to operate over the long run, it was more expensive to purchase than the Exide. Washington, D.C., lawyer James K. Jones explained that he could buy a 1911 Columbia with an Exide battery, “which will make about 75 miles on a charge for $1,750, but the same car with the Edison battery will cost about $2,400. It would appear to make the Edison battery cost $650 more than the Exide battery, though you get more mileage out of the Edison battery and it would probably last longer.” Although Edison maintained that his batteries were less expensive to operate and service, they contained complicated components that were more expensive to manufacture. As a result, Edison could not compete with lead-acid batteries on price. Moreover, the Exide battery manufacturers guaranteed the quality of their batteries. Edison offered guarantees only to commercial truck owners because the company had no control over the installation of batteries on personal automobiles.

Edison aggressively searched for alternative storage battery markets. Pleasure automobile owners were more sensitive to battery purchase costs than commercial vehicle owners, who could amortize those costs over time. In August 1910, he asked P. V. DeGraw, the fourth assistant postmaster general, if the U.S. Post Office would be interested in an electric delivery truck. “If a light high speed (15 mph) delivery wagon carrying from 600 to 1,000 lbs could be made not costing more than 850 dollars & of extreme simplicity, employing electric motor & storage battery that would last for years, could the Post Office dept make use of such a vehicle in cities.”

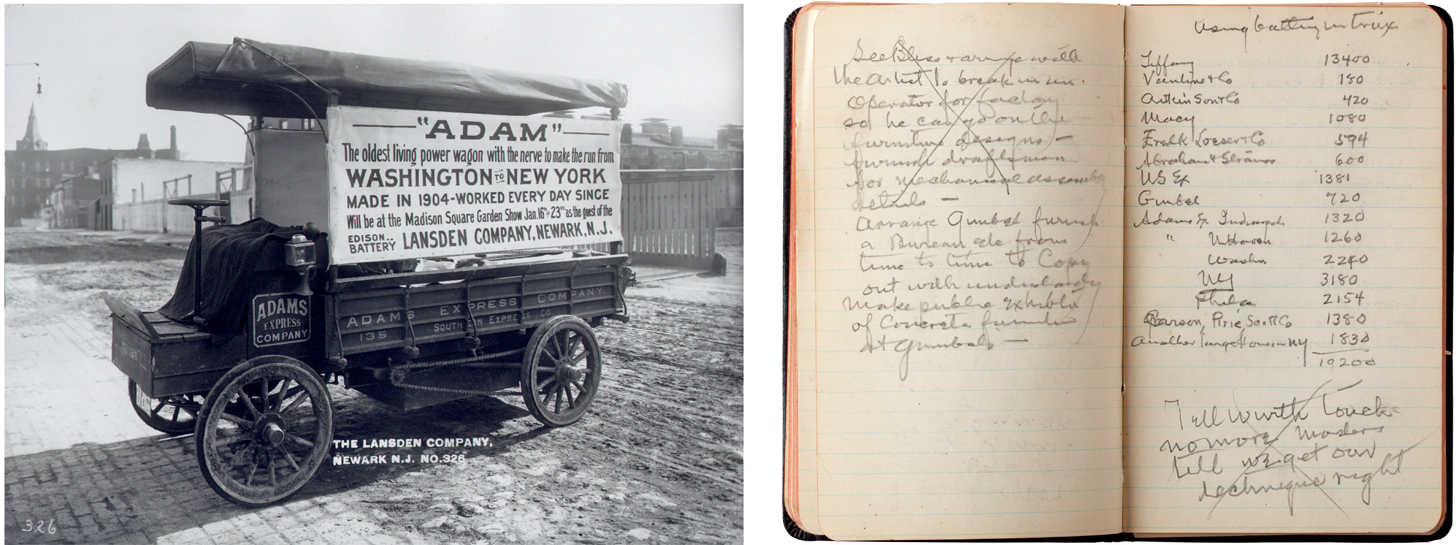

LEFT: The Adams Express Co. tested Edison storage batteries on twenty-two trucks in Indianapolis for five years. Each year, the trucks ran an average of 40,000 miles at a cost of two and a half cents per mile. RIGHT: Edison’s list of the companies using storage batteries in their delivery trucks, including Tiffany, Macy’s, Abraham & Straus, and Gimbels. On the opposite page he jotted notes about exhibiting cement furniture at Gimbel’s department store in New York City.

The electric delivery truck was not a new idea in 1910. According to The Grid, an Edison Storage Battery Co. trade publication, Edison had recognized the potential for electric delivery wagons back in the spring of 1900, while waiting for a ferry to take him back to New Jersey after a business trip to Manhattan. Edison experienced difficulty reaching the Cortlandt Street ferry because of congested traffic. “For two hours he stood watching this conglomeration of loaded trucks, irate teamsters and fretting horses.” As The Grid related, Edison used the time to jot some ideas in his notebook: “Problem—narrow streets. Comparatively large street area covered by horse drawn vehicles. Slow speed. Limited loads. Congestion. Resulting delay and expense therefrom.” Under these notes, he wrote, “Solution—electrically driven trucks, covering one-half the street area, having twice the speed, with two or three times the carrying capacity.”

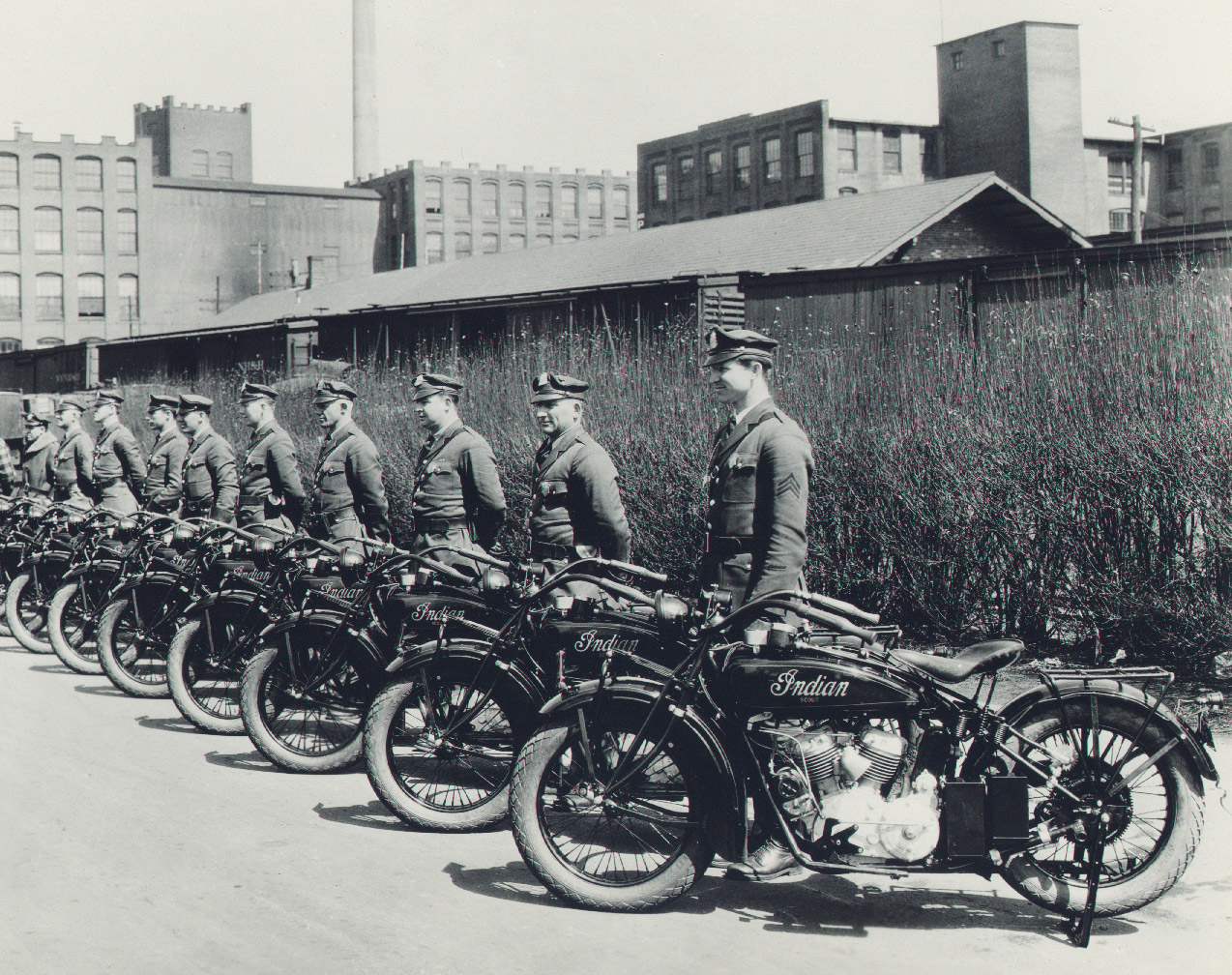

Indian Scout motorcycles equipped with Edison storage batteries. The Hendee Manufacturing Co. (renamed Indian Motorcycle Co. in 1928) manufactured the Scout from 1920 to 1946.

By March 1905, 250 commercial trucks used Edison’s storage battery. Tiffany & Co. in New York operated twenty-one delivery wagons powered by Edison batteries in the fall of 1906. In crowded cities, electric delivery trucks had a few advantages over gasoline trucks. Electric wagons could be operated all day and garaged overnight for recharging. Because they were easier to start, electric delivery wagons were suitable for frequent delivery stops. When the first electric starters were introduced in 1912, electric trucks lost this advantage, but the Edison Storage Battery Co. continued to market batteries for delivery vehicles into the 1920s.

Edison also worked with Ralph Beach, a former General Electric engineer, to develop storage-battery-operated streetcars, and Beach organized the Federal Storage Battery Car Co. in 1910. In March of that year, a Beach streetcar equipped with Edison batteries began operating on a line in Manhattan. On September 25, 1912, three battery-powered Beach railcars, carrying 140 passengers, traveled from Pennsylvania Station in New York to Long Beach, Long Island. The train completed the 25.6-mile trip in fifty-six minutes.

Beach cooperated with Cornelius J. Field, who designed an electric omnibus capable of carrying twenty-eight passengers. “It is not a beauty, it is a very husky car & very practical,” Field told Edison. “It made a run from New York to Atlantic City, 135 miles & back 150 miles without any trouble, speed about 10 miles an hour.” Edison opted not to work with Field because of unfavorable credit reports.

One of the ideas that Edison entertained involved using the motion of ocean waves to charge batteries on lighted navigation buoys. He also liked an idea suggested by the owner of a Norwegian waterfall: use hydropower to charge storage batteries on ships and then sell the electricity in England. Edison’s chief engineer, Miller Reese Hutchison, asked the Electra Cycle Co. in Detroit if they were interested in using Edison’s battery in their electric motorcycle. Electra put Hutchison off, claiming they were undergoing reorganization, but the Hendee Manufacturing Co. of Springfield, Massachusetts—the makers of Indian motorcycles—was interested in Edison’s battery. On November 17, 1911, company president George M. Hendee asked Edison for a meeting to “talk over the question of Edison battery and electric motor for motive power on motorcycles.” Edison agreed, although no record of an actual meeting exists.

Edison examines a storage-battery-powered searchlight in the West Orange lab courtyard, June 10, 1915.

Edison had more success marketing his storage battery as a component of his Country House Lighting system. Designed to provide electricity for homes and farms too remote to buy power from utilities, this system included a gasoline engine, a generator, a switchboard, and storage batteries. The board of directors of Mount Vernon, George Washington’s Virginia home, purchased an Edison lighting system in 1920. The board, “after considering the dangers of oil lamps used up to the present, decided to install electric lights for the protection and preservation of this wonderful old home.” During installation the local contractor concealed the electric wires. For areas inaccessible to wires, Edison provided Mount Vernon with several six-volt portable light batteries to power table lamps.

Edison also attempted to promote the storage battery for submarines. The submarine was an effective weapon in the arsenals of Great Britain, France, Germany, and Russia, but 200 sailors were killed in explosions, accidents, and collisions between 1903 and 1915. Edison believed that many of these accidents had been caused by leaking sulfuric acid from lead-acid storage batteries. When mixed with seawater, sulfuric acid forms lethal chlorine gas. His storage battery, which used no acid, would be a safer alternative. Hutchison told Edison, “Those submarine boys are dead crazy to get Edison batteries on the boats . . . you cannot well blame them when they are taking their lives in their hands every time they make a dive owing to the constant threat of chlorine gas.”

Edison promoted his storage battery as a safe, reliable source of electricity for mines, boats, and ships. According to a 1915 Edison Storage Battery Co. Bulletin, the presidential yacht Mayflower installed 100 Edison cells for emergency radio and lighting.

The U.S. Navy agreed to test Edison’s storage battery and installed them on the E-2 submarine at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in November 1915. However, tests revealed that the Edison cells released explosive hydrogen gas during the recharging process. On January 15, 1916, while the E-2 was in dry dock for the installation of a ventilation system, the submarine exploded, killing five men and injuring ten.

The explosion was a personal embarrassment for Edison who had claimed that his storage battery was safe. The navy’s final report on the accident, sent to Congress in December 1916, did not specifically fault Edison, but concluded that no Edison storage batteries would be used in submarines until they were proven safe. Meanwhile, the navy refitted the E-2 with lead-acid batteries.

DESPITE THE E-2 EXPLOSION and Edison’s inability to market storage batteries for electric vehicles (his original goal), the Edison Storage Battery Co. successfully promoted the battery for a variety of industrial applications, including the powering of truck and automobile lighting and ignition systems, telephone switchboards, and emergency lights for factories, stores, and theaters. Edison’s battery also provided electricity for ships and boats, radio sets, train lighting, and railway signaling and switching equipment.

Safety, durability, and reliability were strong selling points for a small battery Edison developed for miner safety lamps. These lamps illuminated dark mines while reducing the danger of gas explosions caused by candles, kerosene lamps, or other lights with open flames. Edison even produced a safety lamp for the mules used in mining operations. The locomotives used in mines to transport coal and other minerals were also operated with Edison batteries.

Additionally, the Edison storage battery was a lightweight, economical option for powering forklifts and tractors in factories, lumberyards, railroad terminals, and other industrial sites. As the Edison Storage Battery Co. boasted in January 1920, “Large industries, freight and steamship terminals and warehouses are finding that these storage battery trucks and tractors are effecting savings as high as 50% in handling costs besides speeding up organization and eliminating much unnecessary hand labor.”

The Edison Co. continued to manufacture storage batteries in West Orange until 1960, when it sold the business to Edison’s former rival, the Electric Storage Battery Co.