12

“I AM TRYING TO ASSURE A DOMESTIC SUPPLY OF RUBBER FOR THE UNITED STATES—IF THE TIME SHOULD COME WHEN IT IS NEEDED.”

WITH THE FINANCIAL SUPPORT of his friends—automobile maker Henry Ford and tire manufacturer Harvey Firestone—Edison organized the Edison Botanic Research Corporation in 1927 to fund rubber experiments at West Orange and Fort Myers. From 1927 to 1929, he collected and tested the rubber content of thousands of domestic plants. In the last two years of the project, 1930 and 1931, Edison focused on selectively crossbreeding the most promising plant varieties.

Natural rubber is a hydrocarbon polymer found in plant latex. In its natural state, rubber is too soft and unstable for practical use. Vulcanization—a process, invented in the 1830s, of treating natural rubber with heat and chemicals—made it a stable industrial raw material.

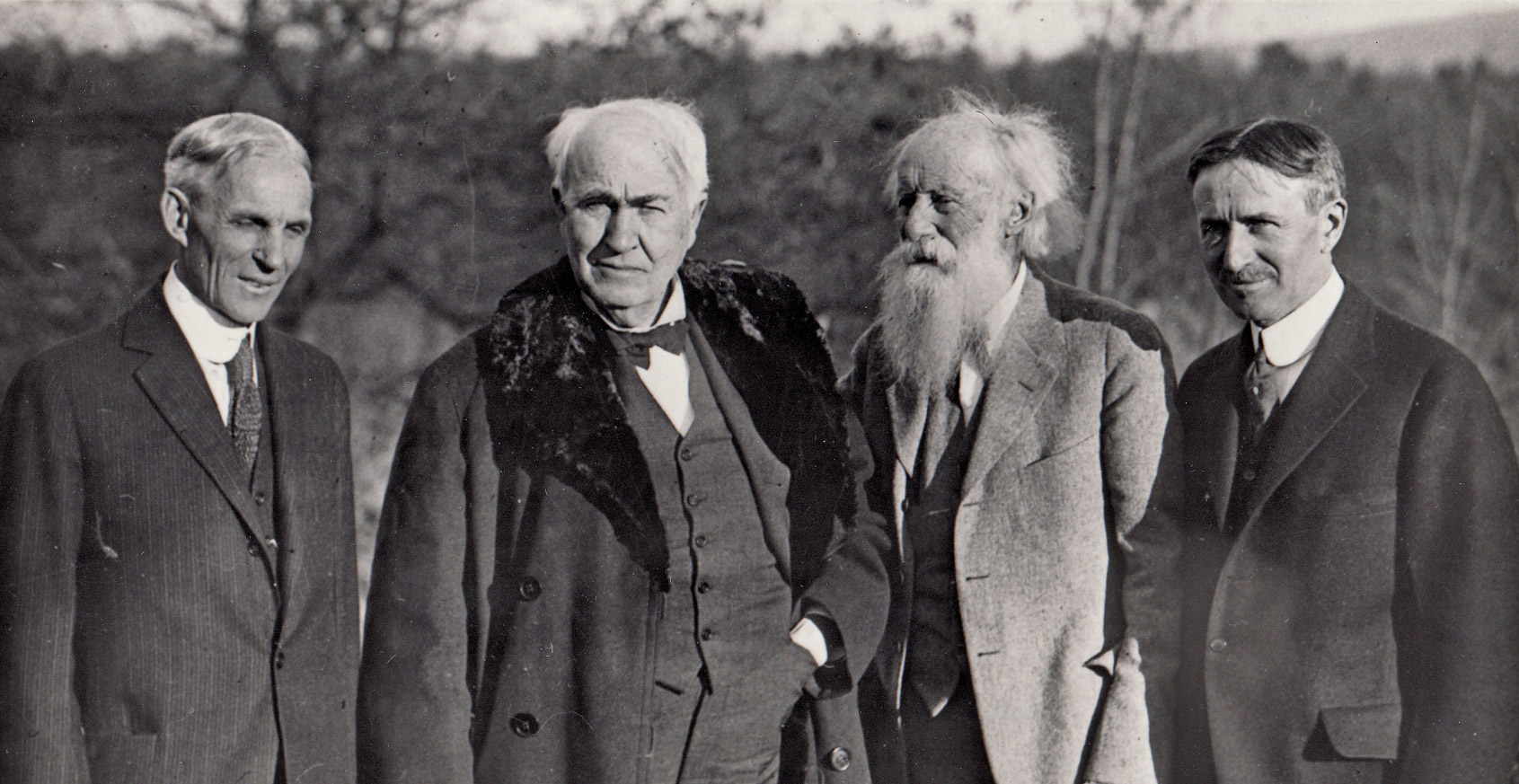

Edison with his camping companions Henry Ford, naturalist John Burroughs, and Harvey Firestone at Yama Farms Inn, Napanoch, New York, on November 15, 1920.

In the nineteenth century, the best source of rubber was a tree native to the Amazon River basin, Hevea brasiliensis. Brazil controlled the world’s rubber supply until 1876, when a British planter smuggled Hevea seeds out of Brazil and planted them in Malaysia. By 1900 the British controlled vast rubber plantations in Malaysia and their other Southeast Asian colonies, and the Dutch had established plantations in Indonesia.

Rubber consumption soared in the United States in the early twentieth century, as demand for automobile and bicycle tires, electric wire insulation, shoes, industrial tubing, and other products increased. By the 1920s, Americans consumed more than 70 percent of the world’s rubber output—but produced none of it.

During the 1920s, political and industrial leaders were concerned that war, political crisis, or natural disaster would disrupt American access to rubber grown on British- and Dutch-controlled plantations in Asia. The Stevenson Plan, enacted by the British government in 1922 to stabilize rubber prices by restricting output, only increased American fears of rubber shortages.

Edison was aware of the rubber problem. Rubber was an important component in his storage battery. During the First World War, he told a reporter that some varieties of American milkweed might produce rubber. He even grew rubber plants in the Glenmont greenhouse. In 1921 he considered making cylinder phonograph records out of rubber instead of the more expensive celluloid and, in 1925, constructed a factory to manufacture hard rubber for storage batteries.

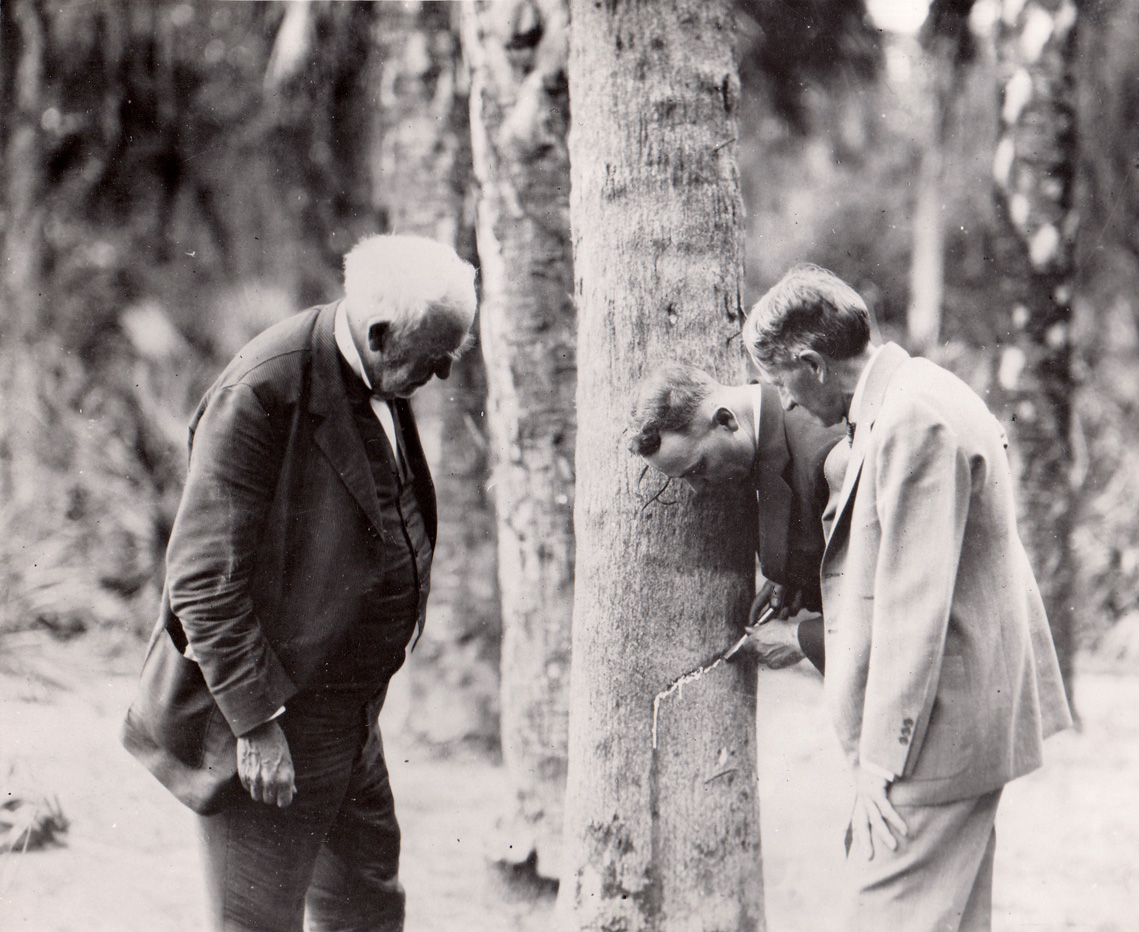

Edison and Harvey Firestone watch M. A. Cheek tap a rubber tree at Fort Myers, March 1925. Cheek was a rubber expert employed by Firestone.

Edison probably discussed the rubber problem during his camping trips with Ford and Firestone, who were heavy users of rubber. Firestone noted after their 1919 camping trip that Edison was remarkably well informed about the industrial elastomer.

As rubber prices increased in the early 1920s, Firestone and Ford became more interested in finding a domestic source. Firestone adopted the slogan “America Should Grow Its Own Rubber” and lobbied the federal government to survey the world’s rubber supply and support domestic rubber research. Ford and Firestone also began supplying Edison with plant samples, seeds, and scientific literature on rubber. Edison conducted his first rubber experiments in 1923, when he investigated the possibility of extracting rubber from milkweed. Edison’s chemists also began experiments on chemical rubber extraction processes. In 1924, Edison received a supply of Brazilian rubber tree seeds and planted them at Fort Myers.

When he began rubber research in earnest in 1927, Edison had a clear conception of the type of plant he wanted: a fast-growing perennial weed with broad leaves that could be harvested mechanically. To expand the area of rubber cultivation north of Florida, he also sought a frost-tolerant plant. Edison explained his objective in a December 1927 Popular Science Monthly interview:

We are looking for an annual crop, something which a farmer can grow in the field, by machinery, which will come to maturity in eight or nine months, which can then be harvested by machinery by processes almost entirely mechanical, with the least amount of hand labor. It must be something which will stand light frosts, for there is no part of the United States where there are not occasional frosts.

Beyond the botanical specifications, Edison carefully estimated the cost of growing, harvesting, and processing a plant crop to supply the 450,000 tons of rubber that the United States consumed annually. From these calculations, he found that he could not produce domestic rubber for less cost than importing rubber from Southeast Asia. As a result, Edison regarded the rubber project as an emergency measure, to be implemented when war or international crisis justified the additional cost of growing domestic rubber.

Although Edison was already familiar with the rubber literature in 1927, he read more extensively on the subject, including abstracts of foreign-language articles provided by an assistant, Barukh Jonas. He needed to know more about what was going on inside plants, so he also studied plant biology. In July 1927, he visited the library of the New York Botanical Library to study tropical rubber plants.

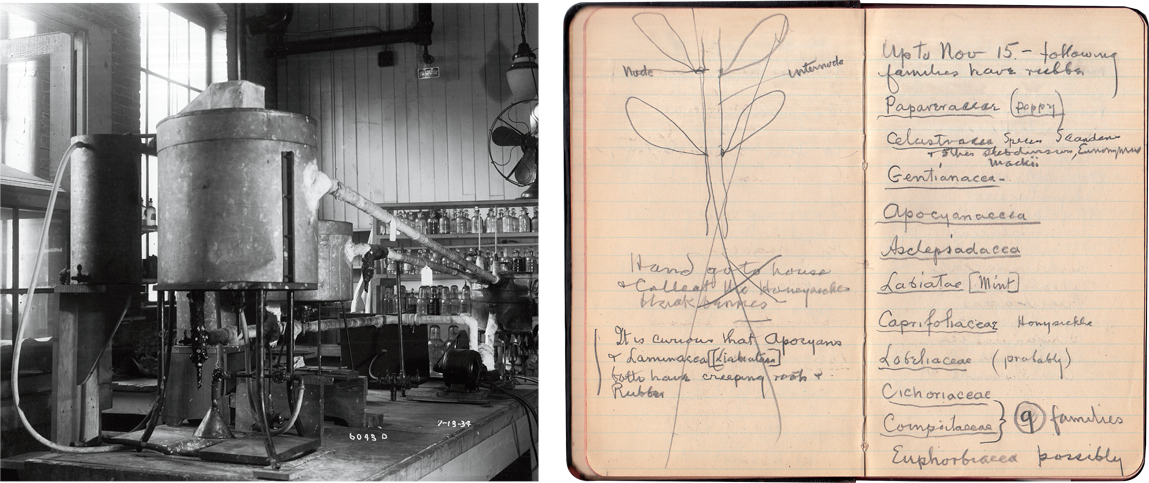

LEFT: Edison used this distiller in the West Orange chemistry lab to recover acetone and benzene after they were used to extract rubber. RIGHT: During the rubber project, Edison studied the physical characteristics of many plant varieties. In this 1929 list, he identified some of the plant families containing latex.

During the spring of 1927, Edison and his chemists developed a process to extract and test the rubber content of plants. Plant leaves were dried and crushed in a meat grinder, then boiled for two hours. After boiling, the leaves were dried and crushed again, then sifted through a mesh screen. Edison used acetone in a Soxhlet extractor—a laboratory apparatus that separated soluble compounds from liquids—to dissolve any nonlatex materials from the crushed plant. After filtering out the acetone and dissolved material, he dried the leaves again. He then added benzene to the leaves to dissolve the latex, which remained after the benzene evaporated. This process could take up to eight hours.

In the summer of 1927, Edison began collecting samples of lactiferous—or milk- producing—plants. He cast a wide net, sending fifteen collectors to Cuba, Puerto Rico, and states along the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic seaboard. Their instructions were simple: “Cut everything in sight.” The collectors kept detailed records, noting plant location, size, and soil condition, then packed, labeled, and shipped the samples to West Orange and Fort Myers for testing. Edison also received plant samples from private collectors and Union Pacific Railroad station agents. To determine the plant’s rubber content, Edison’s chemists weighed samples on sensitive scales or balances, testing more than 1,000 plant specimens in 1927. During the spring of 1928, the inventor supplemented his extensive plant collection with an additional 2,000 samples that he had personally gathered throughout southern Florida, including the Everglades and the Lake Okeechobee area.

At the end of the summer, Edison reported promising results to Ford and Firestone. He told Firestone, “Experiments in the chemical end are progressing fairly well,” and noted in another letter, “Things look very promising for us, and with the cooperation we are getting we certainly will have rubber Trees galore in Florida.” One Edison researcher had identified rubber in 26 percent of the plants he tested. Edison himself estimated that there were more than 38,000 species of plants that contained some rubber.

IN THE FALL OF 1927, Edison sent an assistant, William Benney, to Fort Myers to supervise repairs to the old 1886 laboratory. He planned to use the laboratory for rubber research when he traveled to Florida in January for his annual vacation. The building, which had been used to store surplus furniture, was in disrepair. Edison used the old lab until June, when workers dismantled the building piece by piece and loaded it on a train bound for Dearborn, Michigan, where Henry Ford planned to reconstruct it at Greenfield Village.

Edison examining a goldenrod sample at Fort Myers, 1931.

As the old laboratory left for Michigan, workers completed construction of a new botanic research laboratory. It included a plant nursery, storage barn, gas-powered oven for drying plants, and Portland cement vault used to store documents and supplies. There was also a machine shop with a lathe, grinder, drill press, and other tools for cutting and shaping metal; a photographer’s dark room; a grinding room for crushing plants; and space for a glassblower to make specialized glassware.

Edison’s rubber research team included eight chemists led by Francis S. Schimerka, plant collectors, and two machinists (Fred Ott and Joe Ziemba). Jerome Osborne managed the corporation’s records, herbarium, and reference library. William Benny was the superintendent of the Fort Myers laboratory. Walter Archer worked as a garden laborer in Florida, and Barukh Jonas was employed as a researcher. Edison also employed botanists and a glassblower.

After investigating 17,000 plants and identifying several with some promise—including oleander, flame vine, and black mangrove—in May 1929, Edison concluded that goldenrod, a wildflower that grew abundantly in southern Florida, was the plant. Its rubber yield was not as high as that of some other plants, but goldenrod had a couple of advantages going for it: it grew quickly, and its latex could be easily extracted by Edison’s chemical process. Edison also believed that mechanical harvesting methods could be developed for goldenrod, which would help lower labor costs, and that selective breeding could increase goldenrod’s rubber yield. For this research, he set aside nine acres of land on the grounds of the Fort Myers laboratory to grow varieties of goldenrod.

Edison botanic research lab, Fort Myers, Florida. (Courtesy Edison & Ford Winter Estates, Inc., Fort Myers, FL, www.edisonfordwinterestates.org)

Goldenrod, however, turned out to have several limitations that prevented its adoption as a domestic rubber source. It was difficult to fertilize and did not grow well north of Florida. Edison was also unable to design an efficient mechanical harvester for it.

BY 1931, THERE WAS a rubber surplus, and the conditions that prompted his rubber experiments had changed. The widespread unemployment and reduced industrial production caused by the Depression resulted in lower demand for rubber, and, consequently, its price dropped. Nevertheless, after Edison’s death in October 1931, Mina Edison decided that the rubber research should continue under the supervision of her brother, John V. Miller, who, along with a team of chemists, aimed to improve the rubber yield from goldenrod. In 1934 the Edison Botanic Research Corporation, faced with mounting research costs in an economic depression, considered whether it should stop the project or convince the federal government to assume control of the experiments.

Harvey Firestone and his son, Roger, with Edison in his Fort Myers botanic research lab, March 15, 1931.

In early April, Charles Edison and John Miller met with Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace, who was interested in the research but explained that the government had cut its budget for rubber experiments. Later that month, the U.S. Department of Agriculture agreed to transfer parts of the goldenrod project to its experimental station in Savannah, Georgia.

Lack of funds, however, hindered federal research, and in January 1935, Secretary Wallace asked President Franklin D. Roosevelt to increase funding. Roosevelt did not consider the rubber project as important as other needs and declined to request additional money from Congress. Mina Edison, who regarded the rubber project as an important part of her late husband’s legacy, supported research at Fort Myers until May 1936, when she agreed to dissolve the Edison Botanic Research Corporation.

Ford, Edison, and Firestone outside the botanic research lab in Fort Myers, sharing a laugh.

Edison’s views on the strategic value of domestic rubber were confirmed during the early years of the Second World War, as the Japanese seized control of rubber plantations in Southeast Asia. President Roosevelt appointed a committee that included physicist and MIT president Karl Compton, chemist and Harvard University president James Conant, and prominent financier Bernard Baruch to study the problem. The committee studied earlier efforts, including Edison’s research and later attempts to develop synthetic rubber. Ultimately, however, the committee decided that synthetic materials—not domestically grown latex-bearing plants—offered the best solution to meeting the nation’s rubber needs.

In a 1912 Good Housekeeping magazine interview, Edison predicted that “the kitchen of the future will be all electric, and the electric kitchen will be as comfortable as any room in the house.” Edison’s vision became reality as more American homes became electrified in the early twentieth century and manufacturers began marketing vacuum cleaners, toasters, refrigerators, and other electric appliances.

As phonograph sales steadily declined in the late 1920s, Thomas A. Edison, Inc., sought other products to manufacture in West Orange to keep its factory in operation. In 1928 the company introduced a line of electric appliances— coffeemakers, waffle bakers, sandwich grills, electric irons, vacuum cleaners, and aquarium heaters—that it called the Edicraft Products.

The coffeemaker, named the Siphonator, came in three models priced from $17.50 for the least expensive to $87.50 for the Menlo to $125 for the Manhattan ($230, $1,150, and $1,640 today, respectively). The Menlo and Manhattan models came with serving trays, sugar bowls, and creamers. The waffle baker retailed for $18 and the toaster, for $15.

The Edicraft products reflected the West Orange laboratory’s shift from innovation to product engineering in the 1920s. Laboratory researchers were no longer developing new inventions; they were engineering existing technologies to meet the company’s manufacturing and marketing needs. The Edison Co. purchased the patent rights for the Edicraft line’s most notable technical feature, a durable thermostat called the Birka regulator, which had been invented in Europe.

Edison was not personally involved with the Edicraft line, but his emphasis on high quality and technical performance influenced their design. The Edicraft products would incorporate “good electrical performance, good mechanical performance and an external appearance which would appeal to the buyer and reflect the engineering design within the device.” In other words, performance and attractiveness—not price—were the selling points.

To promote the appliances, the company used Edison’s name, image, and reputation. Edicraft advertisements featured Edison’s signature and his personal message: “Edicraft products are the only electrical appliances developed in my laboratories, made in my factories and authorized to carry my signature.” The company employed what marketing experts today call “brand signaling,” that is, using Edison’s reputation as an inventor to convey the desirable qualities of the Edicraft products. As one ad promised, “The signature of Thomas A. Edison assures you of its mechanical and electrical correctness.”

The company marketed the Edicraft line to upper-middle-class households—families that could afford to buy more expensive appliances but were not wealthy enough to employ servants. The coffeemaker, sandwich grill, and waffle baker offered what the company called “Table Cookery”: “For all those times when it is really a nuisance to go out into the kitchen and prepare a meal, table cookery comes graciously to the housewife’s aid.” To help consumers plan meals, the company issued a booklet with recipes for macaroni waffles, peanut butter omelets, and broiled bananas and bacon.

The Edison Co. introduced the appliances at the beginning of the Depression in the 1930s, when most consumers were sensitive to high-priced products. At a time when the average office worker earned $32.50 per week ($438 today) and competing models sold for $2.50 ($33 today), most could not afford to spend $18 on a waffle baker. The company stopped actively marketing the Edicraft appliances in 1932 and stopped production in 1935.

LEFT TO RIGHT: Edicraft electric iron, toaster, and coffeemaker. (Christopher Bain)

Edicraft ads emphasized Edison’s reputation for reliability and durability, but the appliances were priced beyond the reach of most consumers in the early 1930s.