13

“IF I HAVE SPURRED MEN TO GREATER EFFORTS, AND IF OUR WORK HAS WIDENED THE HORIZON OF MAN’S UNDERSTANDING EVEN A LITTLE, AND GIVEN A MEASURE OF HAPPINESS IN THE WORLD, I AM CONTENT.”

THOMAS AND MINA LEFT New Jersey for what would be his last visit to Fort Myers on January 20, 1931. On his eighty-fourth birthday, Edison dedicated a two-lane drawbridge, named in his honor, over the Caloosahatchee River. The Edisons celebrated their forty-fifth wedding anniversary on February 24. In March, Henry Ford joined them for a visit to Harvey Firestone in Miami Beach, and in April a group of local fifth graders toured the botanic research laboratory. Edison lunched on milk and crackers on the banks of the Caloosahatchee with schoolgirls from the Sarasota Open Air School.

Meanwhile, Edison continued his rubber experiments. As he told the Butte, Montana, Standard, his rubber research was “coming along nicely but slowly.” He expected to live to 100 and, by that time, see rubber plantations in the United States. Edison discussed plans with Henry Ford to mount a rubber exhibit at the 1933 Chicago Century of Progress Exposition. In late May he spilled acid on his hands during a rubber experiment.

Edison returned to West Orange on June 16. Excessive heat and fatigue from the trip prevented his immediate return to the laboratory and forced him to rest at Glenmont. On July 24, Mina’s brother, John Miller, publically denied newspaper reports that Edison had retired but admitted that the aging inventor had visited the laboratory only once since his return from Florida.

Edison collapsed at Glenmont on August 1. While newspapers reported that he was near death, the family summoned his doctor, Hubert S. Howe, who was vacationing on Long Island’s north shore. The family began issuing regular updates on his condition to the press, while the police assigned a protection detail to keep a curious public away from Glenmont. The Peoria, Illinois, Star editorialized, “Nature is about to collect a debt due from the greatest inventor the world has ever known. . . . [Edison] will never be able to work again and this fact, if nothing else may speedily end the old man’s days.”

Edison, however, rallied, and by August 4, Howe reported, “Mr. Edison slept eight hours and had the best night so far. He ate his breakfast with relish, read the morning papers and showed evidence of returning strength and health.” The family stopped the daily press briefings, and the police reduced the guard from five officers to two.

Edison was well enough to take a short drive through the Orange Mountains and enjoy a dinner of tomatoes, peas, fruit, and milk. Forbidden to smoke cigars, he told his doctor, “If I live through my 84th year, I’ll probably live ten years longer.” Dr. Howe tactfully agreed, but he knew better. Edison’s heart and pulse were strong, but he suffered from diabetes, Bright’s disease (of the kidneys), stomach ulcers, and uremic poisoning (symptomatic of kidney failure). As Howe told one reporter, “In my opinion he never will be strong enough to work. He will never be out of danger.”

Crowds of mourners wait on Lakeside Ave. outside the West Orange lab to view Edison’s body in the library, October 19, 1931.

By the end of September, it was clear to the family, friends, doctors, and the press that the end was near. Edison slept comfortably, but the lack of improvement depressed him. By October 13, he was refusing fluids, eating very little, and recognizing no one except Mina. The family resumed daily briefings for the reporters camped on the first floor of Glenmont’s two-story garage. One of Edison’s last visitors was “Uncle Bob” Sherwood, a retired circus clown and old family friend who later published a memoir, Hold Yer Hosses, the Elephants Are Coming! On October 15, Edison slipped into a coma. He died in his bedroom at Glenmont on October 18 at 3:24 am.

James Earle Fraser, a sculptor who had worked with Augustus Saint-Gaudens and designed the Indian Head nickel in 1913, prepared a death mask and cast of Edison’s hands before his body was moved to lie in state in the laboratory library. On Monday, October 19, and Tuesday, October 20, 50,000 mourners filed past Edison’s casket. Employees of the Edison Company paid their respects first, followed by the public. Average men and women, schoolchildren, and the discharged passengers of limousines driven by liveried chauffeurs stood in long lines snaking from the library through the laboratory courtyard and onto Lakeside Avenue.

The casket was moved back to Glenmont for a private funeral on October 21, attended by the family and 400 close friends and prominent mourners, including the Fords, the Firestones, First Lady Lou Henry Hoover, and General Electric president Owen D. Young. Rev. Stephen J. Heben read passages from the Bible, and Phillips Exeter Academy headmaster Lewis Miller delivered the eulogy. A performance of “I’ll Take You Home Again, Kathleen” and “My Little Grey Home in the West” by organist Alexander Russell and violinist Arthur Walsh followed. After the service, Edison was interred in nearby Rosedale Cemetery.

In the days following Edison’s death, his family received sympathy messages from around the world. Benito Mussolini, Pope Pius XI, and German president Paul von Hindenburg were among the prominent world leaders expressing their condolences. Church groups, professional societies, and schoolchildren sent tributes, which Mina carefully preserved in leather slipcases. One letter of sympathy came from Gus Winkler, an Al Capone hit man who wrote to Mina, “Except [sic] my deepest sympathy. Death is something humanity can’t prevent. One must be laid away in life’s everlasting sleep. May he rest in peace.”

THE CANONIZATION OF EDISON began before his death. During the late 1920s, he began receiving awards and tributes from the industries that he had helped establish, including the motion picture industry, which gave him an honorary Academy Award in October 1929. On October 20, 1928, the forty-ninth anniversary of the invention of the incandescent electric lamp, Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon bestowed on Edison a special Congressional Gold Medal. In a short radio speech delivered on that occasion, President Calvin Coolidge described Edison as “the master of applied science” who “literally brought light to the dark places of the world.”

The inscription on Edison’s Congressional Gold Medal reads, “He illuminated the path of progress by his inventions.”

These awards were part of a larger effort to preserve an account of Edison’s massive contributions to society. In the early 1920s, the Association of Edison Illuminating Companies (an electric utility trade group) and the Edison Pioneers (a fraternal organization of Edison associates from the Menlo Park period) began assembling a collection of Edison memorabilia that they planned to exhibit in the United Engineering Societies building in New York. The goal, according to F. A. Wardlaw, the secretary of the Association of Illuminating Companies, was “to place all the original examples of Mr. Edison’s marvelous genius possible of attainment, not only to protect that which still exists from any possibility of loss or damage, but also as a well-mounted tribute of affection and appreciation of one who has done so much to enhance the scientific and industrial progress of his native land.”

Treasury Secretary Andrew W. Mellon presents Edison with the Congressional Gold Medal at West Orange on October 20, 1928.

Edison allowed Wardlaw to inventory historical relics in his laboratory and, in the spring of 1922, approved Wardlaw’s request to repatriate the original tinfoil phonograph, which had been in London’s South Kensington Museum (today the Victoria & Albert Museum) since 1880.

The request sparked a four-year dispute between Edison and the South Kensington Museum. At issue was whether Edison had given or loaned the museum the tinfoil phonograph in 1880. The museum claimed that the phonograph was a gift and refused to send it back, but Edison contended that he loaned the machine, with the understanding that it would be returned upon request. At one point in the years-long exchange of letters and legal papers, Edison’s secretary threatened to go to London and remove the phonograph from the museum personally. Finally, in 1926 the U.S. State Department and the British embassy in Washington, D.C., convinced the South Kensington Museum to settle the matter. Secretary Mellon returned the tinfoil phonograph to Edison during the Congressional Gold Medal ceremony.

Preserving Edison history during the 1920s had personal, corporate, and cultural motivations. As Edison aged, his family became concerned about how history would remember him. Preserving the sites and artifacts associated with his career, the family hoped, would help ensure an accurate portrayal of Edison’s story.

The preoccupation with Edison’s legacy also reflected a broader interest in honoring the nation’s technological heritage. Edison represented a class of inventors and engineers who had ushered in a new technological order in the decades between the Civil War and the 1920s. In the years following the First World War, several technology museums, including the New York and Chicago Museums of Science and Industry, were created to glorify this new order and the values that helped create it, including what historian Mike Wallace called “the belief in progress, reason, the arts and sciences, education and emancipation.”1 For many Americans, Edison’s career embodied these changes and values.

Edison in the West Orange lab with his Edison Effect lightbulb, 1919. In the early 1880s Edison observed that electrons inside an incandescent lightbulb moved from hot to cooler elements. The phenomenon, thermionic emission, became the basis of British physicist John Fleming’s 1904 invention of the radio vacuum tube.

Edison’s cultural status became a valuable commercial asset for his company, which struggled in the highly competitive phonograph market in the 1920s. Consequently, the company used Edison’s persona in its advertising. As one manager noted in 1927,

It is felt and earnestly recommended that full use should be made of the name of Thomas A. Edison and what he has done for the world in the advertising of each of the industries, and that all of these industries should embody in their advertising references to the other industries, and that Thomas A. Edison should be as a bright sun over all illuminating to the fullest extent each one.

The artifacts and documents in the West Orange laboratory became resources that could be used to create a historical narrative suited to the company’s marketing needs. This advertising strategy, combined with a growing public interest in Edison’s life, prompted better care of artifacts and historic documents.

The cot in the West Orange library reminds visitors of the long hours Edison spent working at the lab. (Christopher Bain)

Before the 1920s, Edison’s letters and business records, accumulated over a long career, were stored haphazardly in wooden crates in the library and other laboratory rooms. After the First World War, Thomas A. Edison, Inc., created a Vault Services Department to consolidate inactive records and, in the early 1920s, began identifying and inventorying historically significant material. In 1928 the company created a Historical Research Department and hired a librarian, who began cataloging the notes and documents in Edison’s library.

After Edison’s death, work at the laboratory continued into the late 1930s, when company managers began considering a preservation plan. In a December 1938 memo to Mina, Charles, and Theodore Edison, company executive C. S. Williams lamented the condition of the laboratory. “The present situation here is really appalling,” he noted.

The Laboratory and the buildings surrounding it resemble a jackdaw’s nest. Invaluable relics and models made under Mr. Edison’s continuing regard are hopelessly mixed with paint pots, old cigar boxes, records, seed catalogs, ten penny nails, and a general hodgepodge that is sickening to look at.

Williams wanted the company to preserve the buildings and their contents and to hire more staff to care for the objects and plan exhibits. With family support, the company transformed the laboratory into a memorial, opening the lab as a private museum in 1948.

The Edison family used the Glenmont den for informal entertaining. Decorated with souvenirs and gifts, including a desk set from German munitions maker Frederich Krupp, the room featured a large tree every Christmas. (© Gilbert King)

In 1946, the year before her death, Mina sold Glenmont to Thomas A. Edison, Inc., with the intent of preserving it as “a memorial to my dear husband and his work.” In December 1955, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior designated Glenmont “Edison Home National Historic Site,” and in 1959 McGraw-Edison, the successor to Thomas A. Edison, Inc., deeded the property to the National Park Service. In 1955 Thomas A. Edison, Inc., transferred ownership of the laboratory to the National Park Service. Congress designated Glenmont and the laboratory “Edison National Historic Site” on September 5, 1962.

BY THE 1920S, the original Menlo Park laboratory, long since abandoned, was dilapidated. The state of New Jersey dedicated a memorial tablet near the site on May 16, 1925, in a ceremony attended by Thomas and Mina. In the late 1920s Henry Ford took what was left of the lab and reconstructed it at Greenfield Village, a museum he built near his Dearborn, Michigan, home. Ford stocked the reconstructed lab with original tools and equipment that he obtained from Fort Myers and West Orange. To give the reconstruction an air of authenticity, he shipped original bricks from the New Jersey site and rebuilt the lab on top of Menlo Park soil.

Greenfield Village, a collection of historic buildings that included the Wright brothers’ bicycle shop and Noah Webster’s home, opened on October 21, 1929—the fiftieth anniversary of the invention of the incandescent lamp. Edison, President Herbert Hoover, John D. Rockefeller, and other notables attended the celebration—Light’s Golden Jubilee—which featured a reenactment of the invention of the electric light and was broadcast nationally on the radio.

LEFT: Reconstructed Menlo Park lab at the Henry Ford Museum, Dearborn, Michigan, as it appears today. Dedicated on October 21, 1929, the fiftieth anniversary of Edison’s electric light, the restored lab is part of Greenfield Village, an open-air museum Henry Ford created in the 1920s to preserve significant buildings in the history of American agriculture, manufacturing, and transportation. (From the collections of The Henry Ford) RIGHT: Edison and President Herbert Hoover at Light’s Golden Jubilee, Dearborn, Michigan, October 21, 1929.

In 1932, New Jersey created an Edison Park Commission to consider proposals for a memorial and “museum of light” at Menlo Park. Among the suggestions was an eleven-mile highway connecting Perth Amboy and Plainfield, New Jersey, which would pass through a chain of lakes and parkland visible to motorists. Edison’s daughter Madeleine endorsed a proposal for dual monuments linking Menlo Park and West Orange. The base of the Menlo Park monument would be a stylized dynamo projecting a shaft of light into the night sky. Another idea called for a circular museum building, surmounted by a 175-foot-high shaft bearing an “eternal light.” On February 11, 1937, exactly ninety years after Edison’s birth, the Edison Pioneers announced plans to construct a permanent 135-foot Art Deco–style cement tower at Menlo Park, topped by a fourteen-foot-high light bulb made of segmented Pyrex glass. The tower was dedicated on February 11, 1938.

Edison Memorial Tower in Menlo Park, New Jersey, illuminated at night during the 1930s. The 118-foot high Art Deco–style tower stands on the site of Edison’s original Menlo Park lab.

Edison’s parents had sold their Milan home when they moved to Port Huron in 1854, and Edison’s sister, Marion Edison Page, had purchased the Edison birthplace in 1894, living there until her death in 1900. In 1906, Edison bought the property and asked his cousin, Nancy Wadsworth, to act as caretaker.

Edison paid his last visit to Milan on August 11, 1923, following President Harding’s funeral. As Thomas and Mina, accompanied by the Fords and Firestones, drove down Main Street, a local band played “Yes! We Have No Bananas.” The car stopped in front of a country store, where the mayor gave Edison the keys to the city. Henry Ford, who was considering a run for president, overshadowed the celebration. As Ford moved among the crowd, shaking hands and noting how clean the village looked, he heard shouts of “There’s our next president!”

Before leaving for the next leg of their trip—camping in the woods of Michigan—Edison visited his birthplace and was shocked to learn that his cousin still lighted the home with oil lamps and candles. In 1944 Mina Edison decided to preserve the birthplace as a memorial. It opened as a museum on the centennial of Edison’s birth: February 11, 1947.

Mina Edison continued her annual visits to Fort Myers after Edison’s death, with the exception of the 1943 and 1944 seasons. In the late 1930s, she considered using the Fort Myers property on the east side of McGregor Boulevard for the construction of an Edison Memorial Library. An architect hired in 1939 submitted plans that included a Mission-style library with several reading rooms, an art gallery, and a goldenrod garden. The plan, estimated to cost nearly $100,000 ($1.6 million today), called for the removal of Edison’s botanic research laboratory. In 1941 Mina rejected this idea and hired another architect, who drafted a plan for a smaller library building, an arboretum, a reflecting pool, and preservation of the research lab. For unknown reasons, Mina abandoned the idea before the groundbreaking, but the library was included in a summer 1945 proposal for the creation of an Edison Research University at Fort Myers. The U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development drafted the proposal—calling for a university that would promote independent scientific and technical research and train scientists for war service—and submitted it to President Harry S. Truman. However, the cost was prohibitive, and the plan was dropped.

Edison’s winter home in Fort Myers, Florida. Each February the City of Fort Myers celebrates Edison’s birth with the Festival of Light, an annual event that began in 1938 and today includes a parade, concerts, an antique car show, and an inventor’s fair. (Alamy: © M. Timothy O’Keefe)

In February 1947, Mina donated the Florida estate to the city of Fort Myers. She deeded land on the east side of McGregor Boulevard on the condition that it become a public park dedicated to Edison’s memory. The property on the west side of McGregor Boulevard, along with Mina’s gift of $50,000, went to a nonprofit corporation that would preserve the site as an educational and cultural resource. Upon Mina’s death in August 1947, the city assumed ownership and soon opened the estate to visitors. The city of Fort Myers acquired the adjacent Ford property in 1991, and the combined sites are today operated as the Edison & Ford Winter Estates.

THE PUBLIC’S ADULATION OF EDISON verged on the hagiographic. Elihu Thomson, an inventor and cofounder of the Thomson-Houston Electric Co., thought the Wizard had received too much acclaim. In a 1915 evaluation of Edison for the president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Thomson wrote, “He is undoubtedly deserving of a great amount of appreciation from his fellow men, but it has sometimes in the popular estimation gone much too far, even almost to regarding him as the sole author and pioneer in electrical work.”

Mrs. W. C. Lathrop of Norton, Kansas, encapsulated Thomson’s view when she wrote a letter to Edison in March 1921, thanking him for all of his inventions. “I feel that it is my duty as well as privilege to tell you how much we women of the small town are indebted to you for our pleasures as well as our utmost needs.” Mrs. Lathrop credited Edison with all of the electrical appliances her family enjoyed—even the products he had not invented.

The house is lighted by electricity. I cook on a Westinghouse electric range, wash dishes in an electric dish washer. An electric fan even helps to distribute the heat over part of the house. . . . I wash clothes in an electric machine and iron on an electric mangle [rollers used to wring water from wet clothes] and an electric iron. I clean house with electric cleaners. I rest, take an electric massage and curl my hair on an electric iron. Dress in a gown sewed on a machine run by a motor. Then start the Victrola and either study Spanish for a while or listen to Kreisler and Gluck and Galli-Curci in almost heavenly strains.

If Edison noticed the reference to his competitors (the Victor Talking Machine Co. made the Victrola, and Amelita Galli-Curci was a Victor recording artist), he did not mention this in his response; he simply asked his secretary to “thank her very much.”

Mrs. Lathrop—an upper middle-class, college-educated mother of four and wife of a prominent local surgeon who had entertained the governor of her state—may not have been a typical consumer of the 1920s. But her praise reveals the public’s association of Edison with the technologies that were transforming modern life.

Americans appreciated Edison for his specific inventions, but in the early twentieth century his persona became synonymous with broader values of ingenuity, creativity, and practicality. Edison embodied American faith in material progress, can-do spirit, and optimism in the future. He confirmed the belief that if you had a good idea and worked hard, you would succeed, even if you came from humble origins. In an age that saw the growing influence of large public and private organizations, Edison proved that individuals still mattered.

The cultural assumption equating Edison with innovation endures today. The lightbulb over the cartoon character’s head—the universal symbol for a great idea—is inspired by Edison’s most notable achievement. A number of modern management books draw upon Edison’s methods of collaboration and personal characteristics of creativity, imagination, and persistence to inspire modern innovators.2

In an episode of The Simpsons (“A Tree Grows in Springfield,” original air date November 25, 2012) Homer Simpson becomes obsessed with his “myPad,” prompting his irritated boss, Mr. Burns, to demand that he “unhand his Edison slate.” The reference, a sly joke at the expense of an old man who thinks Edison is responsible for every new technology, speaks to the Wizard’s continued cultural relevance.

Edison was an exceedingly practical inventor and entrepreneur who excelled at bringing together the money, tools, technical and scientific information, and skilled workers needed to operate productive research laboratories. Within the lab, he was gifted at solving technical problems. He was also a capable product engineer who could effectively lead teams to build and test invention models and design manufacturing facilities to mass produce his inventions. It also didn’t hurt that he was savvy about promoting himself. Edison instinctively knew how to project the right mix of authenticity, know-how, and optimism that inspired confidence in his endeavors and attracted investors.

Edison with his tinfoil phonograph and dictating machine in the West Orange library, December 1913.

At Menlo Park and West Orange, Edison established a close relationship between product design, manufacturing, and marketing, demonstrating that the collaboration of these different functions could result in a more innovative operation. His efforts to market his inventions were not always successful, proving that even a good idea combined with the world’s best-equipped laboratory did not always ensure success. Edison did not let failure defeat him, though. If something didn’t work, he tried something else until he got it right.

While the collective impact of Edison’s specific inventions was significant, even more significant was his impact on the process of invention itself. Before Edison became a professional inventor in the early 1870s, the introduction of new inventions was largely the work of independent inventors or mechanics who were fortunate enough to find the financial backing to market their ideas. Machine shops created to support textile mills and other factories were an important source of technical knowledge, but these shops existed mainly to solve manufacturing problems—not to turn out new products. Few companies, if any, supported industrial research. As a result, innovation was a haphazard process contingent on inventors finding the right investors, producers, and promoters.

Edison’s achievements as a telegraph inventor convinced the managers of companies like Western Union that supporting Edison’s laboratory would be an effective way of developing the technologies they needed to control and expand their markets. By establishing a reputation for reliability and by creating productive research facilities, Edison proved to the capitalists who controlled these companies that permanent industrial research laboratories would be more efficient than waiting for independent inventors to approach them with their ideas. Edison thus made technological innovation a safe and reliable investment, demonstrating that corporate capitalism could create and control facilities that turn out new ideas and products on a regular basis.

Because of Edison, team-based industrial research became an important model for innovation in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In this period, a number of large corporations, including General Electric, DuPont, AT&T, Corning, and Western Electric, had established their own research laboratories. According to historian Carroll Pursell, by the First World War there were about 375 research laboratories in the United States, and by 1931 that number had increased to 1,600.3 Companies that could not afford to operate their own labs could use the services of contract researchers like Arthur D. Little, an MIT-trained chemist who created his consulting firm in 1886. Independent inventors like aviation pioneers Orville and Wilbur Wright could still make contributions, but in the twentieth century, teams of researchers working in industrial, government, and university laboratories were the driving force in technical innovation, introducing important developments in chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and nuclear energy, among other achievements.

In recent years, some firms have scaled back their support for research and development or closed their laboratories in an effort to reduce costs, raising questions about how these companies can remain innovative in a highly competitive, rapidly changing economy. Edison’s experience is relevant today because he grappled with the same problems, and we can look to his example for ways to overcome the many challenges of operating a profitable, self-sustaining enterprise. We can stand in his laboratories and see how he organized his workspace. His lab notebooks allow us to see how he translated his ideas into tangible products. His correspondence with his employees, associates, and consumers allows us to learn how he responded to questions about the best way to design, manufacture, and market his inventions. Not only did Edison develop new technologies that formed the basis of entirely new industries, but he also pioneered the movement of investor capital inside companies—a dynamic that continues today and drives much of our economic development.

In October 1930, Edison answered a five-page health questionnaire for Irving Fisher, a Yale University economist, vegetarian, and exercise advocate who had coauthored How to Live: Rules for Healthful Living Based on Modern Science (1915). The questionnaire—which asked specific questions about the respondent’s medical history, diet, and sleeping habits—reveals the state of Edison’s health in the last year of his life.

For an eighty-three-year-old man who no longer had his own teeth, never exercised, bathed less than once a week, chewed tobacco continually, smoked two or three cigars a day, and suffered from indigestion and gas, Edison was in pretty good health. At five feet nine and a half inches, Edison weighed 170 pounds. His heart rate was “about 74,” and his blood pressure was normal for his age.

Genetics may have contributed to his longevity. His mother died at age seventy of what Edison called “worry,” while his father lived to age ninety-four. Edison did not know how long his father’s parents had lived, but his maternal grandfather reached the age of 103, and his maternal grandmother died at ninety.

Because he had no teeth, Edison claimed, he confined his diet to orange juice and six glasses of milk per day. Following the teachings of Luigi Cornaro, a fifteenth-century Venetian who lived to age ninety-eight on a restricted-calorie diet, Edison ate moderately for most of his life. In response to one of the many letters he received asking about his eating habits, Edison said he “followed no special diet, I eat every kind of food, but in very small quantities, 4 to 6 oz to a meal.” In 1921 he listed the following meal plan: For breakfast he drank a cup of coffee (half milk, half coffee) and ate two pieces of toast, plus another piece of toast with two small sardines. Lunch was a glass of milk with two pieces of dry toast. For dinner, Edison drank two glasses of milk and ate three pieces of dry, thin toast, a small piece of steak, and a small baked potato, followed by one piece of chocolate with nuts.

Edison did not follow Fletcherism, a popular food trend named after Horace Fletcher, a nineteenth-century health-food promoter who believed food should be chewed thirty-two times before it was swallowed. When the New York Times asked Edison in 1914 if he Fletcherized, he replied, “Fletcherize nothing, bolt I bolt my food; that’s the thing. Fletcherized food is too quickly digested. All animals bolt their food.”

Edison also had strong views on sleep. In Fisher’s survey, he noted that he slept with his windows open for about six hours a night—an increase from the less than five hours he typically slept throughout his life. “Eating too much is a habit, just like sleeping too much,” Edison argued. “If the sun never set men would get out of the habit of sleeping, they would get used to going without.” He believed sleep was an evolutionary holdover from early human history, when there was little to do after sunset, and predicted, “The man of the future will spend far less time in bed than the man of the present does, just as the man of the present spends far less time in bed than the man of the past did.” Of course, the technologies he developed—like the electric light, phonograph, and motion pictures, which extended day into night—may also have contributed to sleep-deprived modern life.

In August 1911, Edison summarized his rules for a long life: sleep six hours, never retire, study music, and eat a handful of solids at each meal.

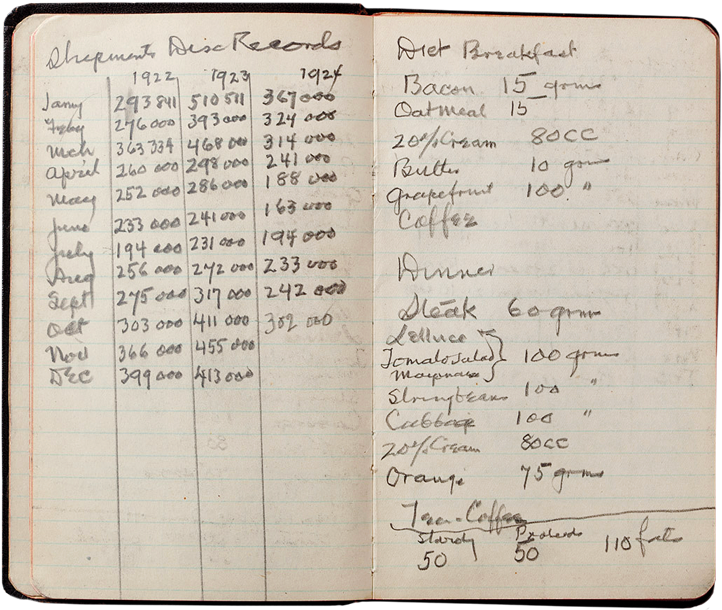

Mixing personal and business affairs, Edison tracked the shipment of phonographs and his daily food consumption in this 1924 pocket notebook.

Edison on the front lawn of Glenmont, June 30, 1917.