THERE ARE TWO THOMAS EDISONS: the mythic, larger-than-life “Wizard of Menlo Park”—a tireless heroic inventor with an inexhaustible supply of ideas who gave us light, sound, and moving pictures—and the Innovator who spent his life solving technical problems in shops and laboratories and creating companies to manufacture and market new technologies.

One Edison could not have existed without the other. The Wizard inspired faith in financial backers, business partners, employees, and consumers, providing the Innovator with the resources and support he needed. The Wizard was based on a solid record of accomplishment; without the successes of the Innovator, no one would have paid any attention to the Wizard.

Both personas are significant. Edison’s fame reflected American faith in technological progress and reaffirmed a compelling national narrative: a young man with no family connections, no wealth, and little formal education rises through hard work, ingenuity, and perhaps a little luck to become the preeminent inventor of his age. Edison’s story reveals a different picture: a talented inventor and entrepreneur who worked within and took advantage of broader social, cultural, and institutional forces that ushered in the modern age of high-tech industrial capitalism, globalization, and consumerism.

The Wizard often overshadowed the Innovator, contributing to misleading assumptions about Edison. Maurice Holland, the director of the National Research Council’s Division of Engineering and Industrial Research, encountered both Edisons during a 1927 visit to the West Orange laboratory. Holland scheduled five days to study Edison’s method of invention. He wanted to know if Edison’s success could be attributed to his personal genius or the organization of his laboratory.

Edison welcomed Holland cordially, invited him to stay as long as he liked, and told him he did not need five days. “There is no organization; I am the organization,” Edison proclaimed. When Holland asked Edison how many experiments were in progress, the Wizard answered, “I haven’t any idea. I have enough ideas to keep the laboratory busy for years and break the Bank of England.” Holland described the laboratory as “a number of rambling buildings without any definite plan, obviously a product of evolution” and observed “elaborate records, detailed cost accounting, scheduling, requisitions and myriad devices considered necessary under the heading ‘Business Organization’ has no place here when judged by the practical standards of accomplished results.”

The Innovator, of course, knew exactly how many experiments were under way in the laboratory and precisely what his experimenters were doing. His businesses were organized; the laboratory’s physical layout was planned; and—as for the lack of financial records—187 linear feet of accounting records and 216 linear feet of requisition records survive in Edison’s archive.

Holland got some things right. He accurately observed Edison’s reliance on detailed experimental records and recognized his team approach to invention. After what he called “persistent questioning,” Holland coaxed from Edison his method of experimentation:

First state the problem clearly . . . formulate it, then write down every conceivable means of solution, including, as he expressed it ‘the damned fool ideas, for they sometimes work,’ build an experimental model to prove the principle, put it to every conceivable test encountered in actual service, standardize it for manufacture, turn it over to production experts for commercial production.

This is a fair enough description of how Edison worked, but Holland said nothing about how much time Edison spent on administrative, manufacturing, and marketing problems.

Holland’s report illustrates the difficulty of sorting Edison myth from reality. Edison contributed to this problem by reducing invention to witty sayings like “Genius is 1% inspiration, 99% perspiration”—folksy axioms that entertained newspaper readers but did nothing to explain how he operated. Edison attributed his success to hard work and what a San Francisco newspaper in 1898 called his “dogged persistence.” Edison’s legendary capacity for hard work, curiosity, and entrepreneurial drive are relevant, but these characterizations oversimplify a complex process.

Thomas A. Edison, Inc., combined the qualities of Edison the Innovator (scientific knowledge, teamwork) with the Wizard (optimism, humor, persistence) in this 1940s magazine ad.

Compounding the mystery are misleading assertions about Edison’s role as an innovator. Henry Ford, a close friend for the last two decades of Edison’s life, called him “the world’s greatest inventor but worst businessman.” In his 1985 book Innovation and Entrepreneurship, management expert Peter Drucker erroneously claimed that Edison “so totally mismanaged the businesses he started that he had to be removed from every one of them to save it” and that Edison’s principal ambition was to become a “tycoon.” This view of Edison as a poor business manager is often declared without the benefit of research on the organization and management of Edison’s companies.

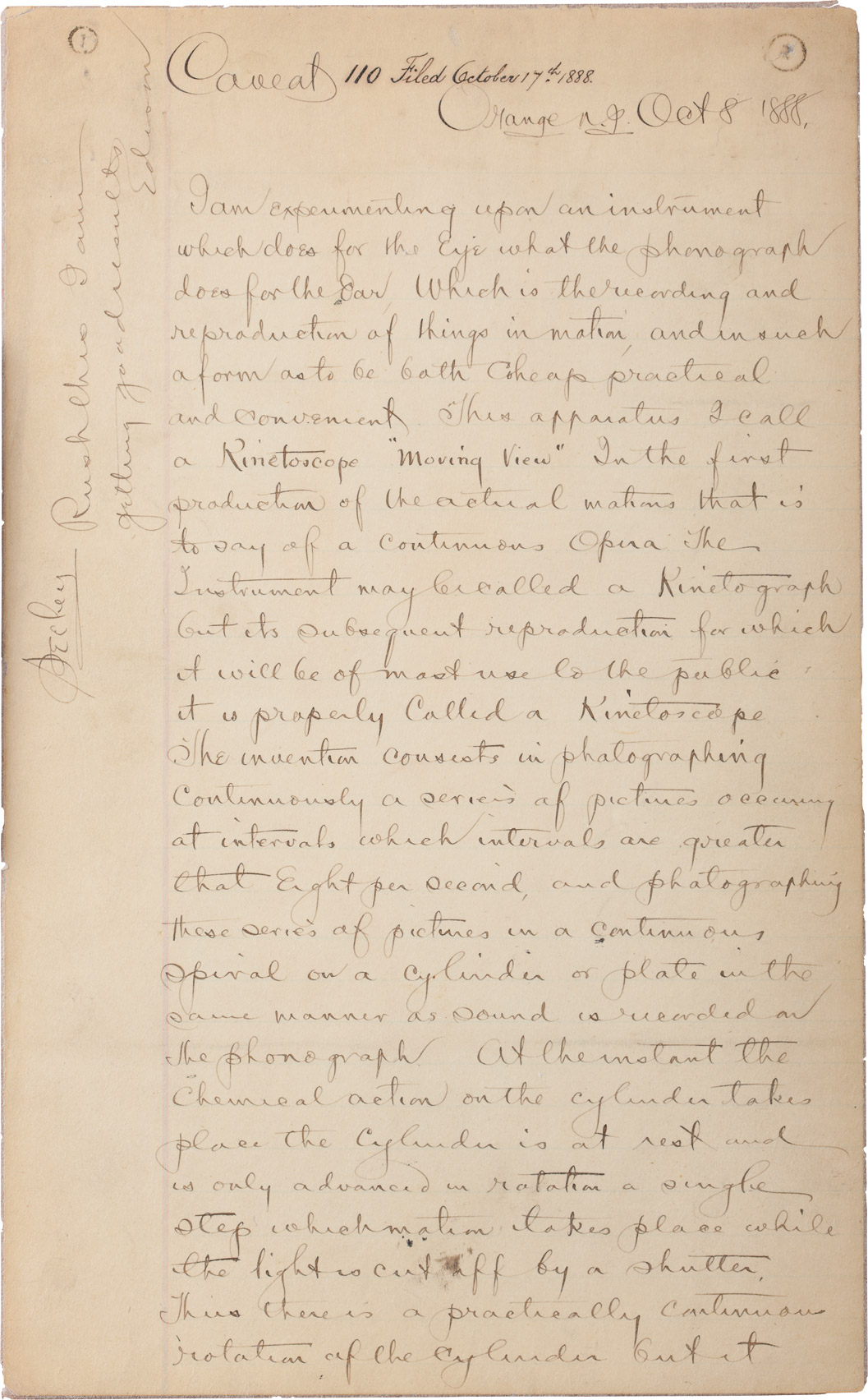

First page of Edison’s October 1888 patent caveat, describing his plan to invent a motion picture camera.

With millions of documents, thousands of historic photographs and artifacts, and several carefully preserved historic sites and museums in the United States, we have the resources for a fresh examination of Edison. This book traces Edison’s long career, from his formative years as a telegraph inventor in the early 1870s, to his first major research laboratory at Menlo Park, to the West Orange laboratory where Edison worked during the last forty-five years of his life.

Following a brief review of Edison’s childhood and youth in this introduction, the first chapter examines his first steps toward becoming an inventor in the early 1870s. Subsequent chapters focus on the Menlo Park and West Orange laboratories as organized research facilities or on specific technologies, including the phonograph, the electric light, motion pictures, ore milling, Portland cement, the storage battery, and rubber. Chapters also describe Edison’s transition from Menlo Park to West Orange and his role as an innovator during the First World War. A concluding chapter discusses Edison’s final illness and death and his memorialization through the preservation of historic sites and museum collections associated with his life.

Sidebars introduce lesser-known Edison inventions or products, including the electric pen, the electric railroad, the talking doll, X-ray equipment, and the Edicraft appliances. Sidebars also explore Edison’s laboratory notebooks and the 1880s “battle of the currents.”

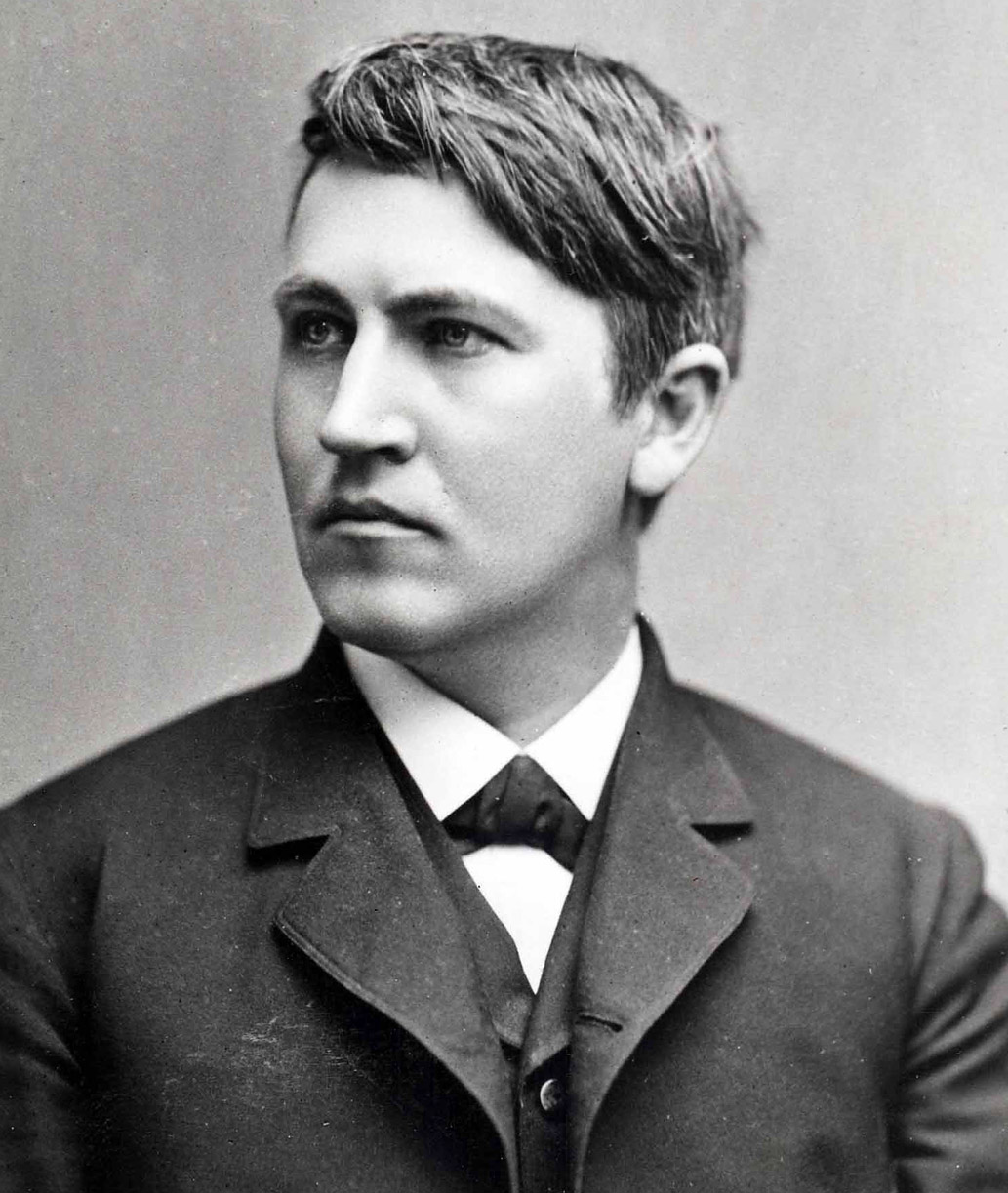

Edison in June 1881.

In reframing Edison, this book argues that innovation is not simply a linear “idea-to-product” process, where inventors take an idea, build a prototype or working model, put the model into production, and sell the manufactured articles to consumers. Instead, a close examination of Edison’s innovation methods reveals a social process involving the interaction of inventors, manufacturers, marketers, consumers, and others answering important questions about which technologies society should develop and how they should be designed, produced, marketed, and consumed—answers shaped by the goals, values, and assumptions of the people involved in the process. From this perspective, Edison’s inventions reflected the evolution of broader societal conditions, the goals of his investors and business associates, and the information and resources available to him, in addition to his own perceptions of what society needed or wanted.

Edison relied on the technical and scientific reputation of his laboratory to market his Portland cement.

THE CHARACTER TRAITS that defined Edison emerged in his childhood and youth. Edison was born in Milan, Ohio, on February 11, 1847, the youngest of Samuel and Nancy Elliott Edison’s seven children. Milan was connected to Lake Erie by a short canal, which helped the village become a prosperous shipbuilder and grain port. Milan’s thriving economy allowed Edison’s father—a carpenter, shingle maker, and land speculator—to build a sturdy brick house on the bank of the canal. Edison left Milan when he was seven years old, but he recalled the grain elevators along the canal and the busy shipyard. He also remembered the town square filled with wagon teams delivering barrel staves and covered wagons staged in front of his house, preparing for their journey to the California gold fields.

Milan’s economy declined the early 1850s after the opening of a railroad between Mansfield, Ohio, and the Lake Erie port of Sandusky allowed grain shippers to bypass the canal. Samuel Edison moved his family to Port Huron, Michigan, in the spring of 1854 to find better opportunities. In Port Huron, Samuel sold lumber, speculated in real estate, and built and operated an observation tower that offered tourists views of Lake Huron. Samuel also worked a ten-acre vegetable farm. Edison remembered working on this farm, planting corn, onions, and other vegetables. With a horse and wagon, he helped Samuel sell the crops door-to-door.

Edison may have learned entrepreneurship from his father, but his mother, a former schoolteacher, was largely responsible for his early education. Edison attended school for less than a year. There is no evidence that a teacher dismissed Edison because of a learning disability; rather, the family’s limited resources may have prevented additional formal schooling. It was not uncommon for boys of Edison’s age and social class in the mid-nineteenth century to receive the basics of reading, writing, and simple arithmetic and then to take jobs to help supplement family incomes.

Edison credited his mother with teaching him how to read. As he told New Jersey grammar school students in 1912, “My mother taught me how to read good books quickly and correctly, and as this opened up a great world in literature, I have always been very thankful for this early training.” As an adult, Edison was a voracious reader, and his ability to read and absorb large quantities of printed information contributed significantly to his success.

LEFT: Edison’s father, Samuel Edison Jr. RIGHT: Edison’s mother, Nancy Elliott Edison.

Nancy, a devout Methodist, may have taught Edison to read from the family Bible. Edison also had access to Samuel’s library of political tracts, which included works by Thomas Paine. Beyond basic reading and writing, Edison demonstrated an early interest in science, reading elementary textbooks like Richard Green Parker’s First Lessons in Natural Philosophy (1859). Archeological studies of Edison’s Port Huron home have uncovered remnants of a chemistry set.

The railroad and telegraph—two technologies that transformed nineteenth-century America—gave Edison his first significant employment opportunities. In 1859 Nancy gave him permission to work as a newsboy for the Grand Trunk Railway. Each morning, twelve-year-old Edison boarded a 7:00 a.m. Detroit-bound train to sell newspapers, magazines, candy, and fruit. The train returned to Port Huron at 9:00 p.m. Soon, Edison employed two Port Huron boys to operate stores selling magazines, vegetables, and butter. He stocked the stores with produce purchased in Detroit at wholesale prices or from farmers along the railroad. To save on shipping costs, Edison used unoccupied space in the baggage car and enlisted the cooperation of railroad workers by selling discounted butter and vegetables to their wives. Edison expanded his news business by hiring boys to sell newspapers on other trains.

In early 1862 Edison purchased a secondhand printing press and began publishing a newspaper, the Weekly Herald, in the train’s baggage car. For a monthly subscription of eight cents, the newspaper provided readers with local news, train schedules, birth announcements, advertisements, and egg, butter, and vegetable prices. In his spare time, Edison experimented with chemicals in the baggage car, until a jar of phosphorus caught fire and the angry conductor, Alexander Stephenson, tossed the printing press and chemicals off the train.

Edison’s birthplace, Milan, Ohio. (Courtesy of Edison Birthplace Museum, Milan, Ohio)

Edison noticed a loss of hearing at an early age. No one knows the cause of Edison’s deafness, but he later blamed it on conductor Stephenson who, depending on the account, either boxed Edison’s ears or lifted him by the ears onto a railcar. A doctor who examined Edison later in his life believed that the hearing loss was caused by a congenital defect, but scarlet fever, which Edison contracted soon after the family moved to Port Huron, may have contributed to the problem. Whatever the cause, Edison claimed that his hearing loss did not seriously hinder his work because it allowed him to concentrate and disregard extraneous noise.

An act of bravery in the fall of 1862 gave Edison a life-altering opportunity. While standing on the Mount Clemens, Michigan, station platform, Edison saw the stationmaster’s three-year-old son in the path of an oncoming railcar. As Edison’s secretary later recalled, “Springing to his assistance, Edison succeeded in getting the boy off the track a few seconds before he would have been crushed.” In gratitude, stationmaster James Mackenzie fed Edison dinner for three months and, more important, taught him telegraphy.

In the winter of 1863 the fifteen-year-old Edison took his first job sending and receiving telegraph messages at a jewelry store in Port Huron. The following summer he worked as a telegraph operator for the Grand Trunk Railway in Stratford Junction, Ontario, and between 1864 and 1867 he was employed as an itinerant telegrapher in cities throughout the Midwest and South, including Cincinnati, Fort Wayne, Indianapolis, Memphis, and Louisville.

Map of the Grand Trunk Railway, where Edison worked as a newsboy in 1859 and as a telegrapher in the early 1860s. (David Rumsey Map Collection)

Most telegraphers in the post–Civil War 1860s were young, unattached men who moved from town to town, looking for positions in telegraph offices. They were part of a community of skilled operators who acquired a reputation for leading carefree, dissolute lives. Operators were expected to have a basic understanding of the technology so that they could maintain, repair, and adjust equipment, including the chemical batteries that powered the system. As a telegrapher, Edison acquired these skills, but he was part of a smaller group of operators who wanted to further their education through self-study and to design improved telegraph equipment.

LEFT: The young Edison read about science in textbooks like Richard Green Parker’s First Lessons in Natural Philosophy. (Courtesy of Ames Historical Society) RIGHT: Edison at age fourteen.

Because Edison was better at receiving telegraph messages (listening to the clicks of an incoming signal and transcribing the message on paper) than sending (tapping outgoing messages on a telegraph key), he worked the night shift, when press services transmitted long newspaper copy. Working nights gave Edison ample time to read, study the technical literature, and experiment. In an early notebook Edison kept when he worked in Cincinnati in 1867, he sketched ideas for improving telegraph equipment, including designs for new relays that would increase the strength of incoming telegraph messages; repeaters that would allow the transmission of messages over longer distances; and multiple telegraph circuits, designed to send more than one message over the same wire.

LEFT: Edison’s early technical education included drawing designs for telegraph circuits and relays, as seen in these pages of a pocket notebook from the late 1860s. RIGHT: Edison’s understanding of electricity and magnetism, crucial to his success as a telegraph inventor, was influenced by the research of British scientist Michael Faraday. The work of Faraday, inventor of the electric motor, laid the scientific foundation for electrical technologies in the nineteenth century. (Courtesy Wikimedia Foundation)

With spare money, Edison purchased books, tools, and equipment to conduct experiments. Among the technical books Edison read in the late 1860s were Michael Faraday’s Experimental Researches in Electricity (1855) and Dionysius Lardner’s Electric Telegraph (1867). Edison’s frequent book purchases nearly led to his being shot in 1866 in Louisville, where he bought fifty volumes of old North American Reviews at a junk auction. As Edison recalled:

One morning after getting through the press I took 10 volumes on my shoulder & started for home. It was rather dark & while nearing home which was a room above a saloon I heard a shot & stopped. A policeman ran up & grabbed me by the throat. Fortunately I knew him. He had yelled but I being rather deaf did not hear . . . he supposed I had stolen the books.

Edison left Louisville and returned home to Port Huron in the fall of 1867 for an extended visit with his family. After spending a few months in Port Huron, he became restless and asked a telegrapher friend who worked in Boston if there were any jobs for him. The friend told Edison to come immediately.