As discussed in the preceding chapter, the goal of a unified Germany was already being actively pursued during the first half of the nineteenth century. Yet, as was the case with France, there was much law to unify. The Napoleonic domination of German states and principalities during the first decades of the nineteenth century resulted in the adoption of the Code Civil by the states and principalities west of the Rhine River and Baden. This only added to the large number of local laws extant, including a Roman law that had been received in its totality by many principalities in 1495.2

Once a still-dismembered Germany attained its independence from France, writings advocating legal unification began to circulate. The most influential of these was a pamphlet published in 1814 by Anton Thibaut, a professor at the University of Heidelberg. He argued that the Roman culture that was an integral part of the received Roman law was not Germany’s and advocated enactments that would reflect German culture, written not in Latin, but in German. This pamphlet spurred a movement that encouraged the enactment of Germany’s private law codes: the Commercial Code, Handelsgesetzbuch, (hereinafter HGB) in 1897 and the Civil Code, Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, (hereinafter BGB) in 1900.3

Thibaut’s proposed Germanic law was opposed by the so-called Historical School. This school of thought viewed law as a set of norms developed in response to society’s need for change. For the Historical School, it was unreasonable to freeze the law, so to speak, by codifying it, especially when scholars were unable to agree on what law was needed and on how best to draft it. This point of view was advocated by Friedrich Carl von Savigny in his famous pamphlet of 1814, On the Vocation of Our Times for Legislation and Legal Science (Vom Beruf unsrer Zeit für Gesetzgebung und Rechtswissenschaft).4 Savigny argued for an intensive study of German legal history, prominently including the received Roman law, especially what he considered its superior analysis.5

Although Savigny rejected the idea of natural law as the basis for the new German law, he accepted the natural law point of view that legal science should pursue 410principles that would inspire an orderly and coherent legal system. One of his pupils, Georg G. Puchta, devoted himself to “systematizing” Roman law by applying to it a “pyramidal” analysis that would produce general or organizing concepts from which other, more specific ones would be derived.6

Puchta also relied on the “national spirit of the German people” (Volksgeist) as a natural-law-based principle that would help select the rules most consistent with that spirit.7 Yet, as also pointed out by von Mehren and Gordley, “[h]owever, abstract, doctrinal thinking dominated Puchta’s own writing to such an extent that the Volksgeist had no practical significance in his work.”8

Bernhard Windscheid, another pupil of Savigny, was less theoretically inclined than Puchta and wrote an exhaustive Roman law treatise, Lehrbuch des Pandektenrechts, whose purpose it was to serve as the ultimate reference work for scholars, judges and practitioners. This writing proved influential in the codification of the BGB, which was undertaken shortly thereafter.9

By the middle of the nineteenth century, legal positivism10 had become an ally of German nationalism. Nationalists and legal positivists advocated that, history aside, a national government had the inherent power to promulgate its own law. Legal positivism claimed support from the scientific positivism widespread among the increasingly prestigious German universities and research centers. Scientific positivism maintained that valid knowledge required: (1) empirical observation; (2) formulation of hypotheses based upon what was observed; and (3) a verification of the hypotheses by equally empirical means.

Legal positivists, relying on scientific positivism, rejected natural law as based upon metaphysics instead of the above steps. However, what German legal positivists understood as empirical research differed sharply from what natural or even the pioneering social scientists of the era understood by it. For the natural and social scientists, scientific legal research required not only an objective description of the law as found in written and unwritten or customary sources, but also an equally objective description of the manner in which it was being applied or observed. In addition, it required an analysis of its interaction with society’s economic, religious and ethical beliefs.

In sharp contrast with the scientific method of the exact and social sciences, the research of the nineteenth-century German “legal scientists,” inspired by Puchta’s methodology, was confined to what was observed and verified within a finite set of Roman law texts. Puchta’s followers looked for what could be identified as essential components of Roman legal institutions as found, for the most part, in the Corpus Juris Civilis, known in Germany as the Pandekts, and the law derived from it 411(Pandektenrecht). Accordingly, Puchta’s followers were known by the English designation “Pandectists.”11

If a Pandectist wanted to find out the essential components of, say, the right of possession, he would look at the Roman law remedies for the protection of possession such as in actions and “interdicts” as well as in the defenses against them. He would study the opinion of jurists, the praetor’s edict and his formulas, Gaius’ and Justinian’s Institutes, and the collection of laws. Once all these sources were briefed and classified, he would identify the common elements of these remedies and come up with a formula such as:

Possession = Physical control of the thing + The intent to possess it as an owner (Animus Rem Sibi Habendi or Animus Dominii)

Yet, what if the Pandectists missed an important source or relied on a questionable medieval addition or “interpolation” to a juristic opinion or edict? For example, what if the above components of possession disregarded remedies granted by a Praetorian edict not to owners, but to legitimate possessors such as bailees or carriers who did not intend to possess as owners? Or, what if they had unknowingly relied on an interpolation that granted possessory remedies only to Roman citizens (“quiritary owners”)? In that case, an adjustment of the earlier “scientific” finding would have to be made and the rewritten formula would lead to a more inclusive concept of possession:

Possession = Physical control + The intent to possess legitimately (Animus Possidendi)

In theory, the Pandectists should have produced a “truthful” and precise set of concepts, rules and principles of law making and interpretation, also referred to as “legal institutions.” By connecting these institutions and establishing their hierarchy, an analytical system could have been created to give the law maker, adjudicator and interpreter a feeling of “scientific” certainty.

To illustrate, assume that the same research conducted on possession was conducted on ownership and on other rights related to things immovable and movable. Thus, similar in rem remedies were given to the following: users of immovables whose rights to use were granted by owners, lawful possessors thereof, holders of life estates, easements or servitudes, and mortgagees and pledgees. Finally, assume that after a thorough study of the Pandectists, the researcher concluded that the only rights in rem granted were those just listed. If this finding could not be disproven or qualified by showing that a right may have existed but lacked a remedy such as ius distrahendi,12 the researcher could proudly announce that he or she had discovered an essential feature of the pyramidal or systematic concept of a right in rem: by nature or essence, these rights were limited in number (numerus clausus). Such a “scientific” finding would lead to the principle or rule that only the rights in rem on the researcher’s list were entitled to legal protection, including the ability to register them in the appropriate land or chattel registry.

If the reader finds a resemblance between this method of “system building” and that of French eighteenth-century neo-scholastics such as Robert Pothier, he is not mistaken. For, in order to conclude that because the Pandectists only protected a certain number of rights in rem, all rights in rem (whether found within or without the universe of the Pandectists) were limited in number, a huge metaphysical and unempirical leap had to intervene and it was buttressed solely by the Aristotelian essences. Both the Pandectists and the neo-scholastics were believers in the Aristotelian essences and in the metaphysical truth of logical sounding definitions and classifications. The major difference between the Pandectists and, say, Pothier, was that their research, albeit much deeper and more detailed, was confined to the universe of rules, concepts, and principles of interpretation found in the received Corpus Juris Civilis. Pothier relied not only on Roman law, but also on the writings of legal scholars, including natural law thinkers, and, although less frequently, on his own observations of French contract practice.

When it came to adapting the law to changing socio-economic circumstances, both the French neo-scholastics and the Pandectists were equally inflexible. Encouraged by Savigny’s high opinion of the analytical skills of Roman jurists, the Pandectist assumed that his “finding” of the applicable Roman law was also a finding of best possible law, and that if factual and socio-economic circumstances changed, all that had to be done was to adjust that best possible law, i.e., Roman law, to the new circumstances.

Yet, what if the found (and received) Roman law prevented such an adjustment? Consider the following incident.13 In order to rebuild Germany’s railroad system after its destruction in the Second World War, a group of lenders agreed to lend, but only if they could perfect their security interests in the railroad equipment, tracks and land beneath them. They took into account that the repayment of their loan required that the railroad operators be allowed to possess and use the above collateral. They also concluded that the best method to secure their loan was to create the equivalent in German law of an Anglo-American security or guaranty trust. In it, the lender-trustee would acquire a right in rem in the railroad equipment, rolling stock, tracks and land beneath them, while the rail operator would be the possessor of the collateral. This security interest would have to be recorded in order to protect the lenders against competing rights by other, subsequent creditors and purchasers of the collateral.

At first, the German land registrar rejected such a recording based on the following reasoning:

The legal nature (meaning the essence) of such a security interest (the trust) is not a right in rem. If it is a right in personam, obviously it cannot be registered in the Land Registry because it records only rights in rem. If the trust purported to have in rem effects, especially on the land beneath the rails, it has to qualify as one of the rights set forth in the BGB Sections 873–928. 413If it was not one of them, which it does not appear to be, it could not be recorded in the land registry.14

When asked whether the enactment of a statute adding this “new” right in rem to the list could resolve the problem, his answer was that the list in the BGB was unchangeable because it embodied legal-scientific truth. Such truth, incidentally, came directly from the writings of Roman jurists on rights in rem as collated and interpreted by Pandectists. Ultimately, the land registrar was able to find a way to record the rights in question. Yet, had he not done so, would he have been justified in rejecting such a momentous recording, even following the enactment of enabling legislation, based on his “Pandectistically-inspired” findings and conclusions?

Not surprisingly, Rudolf von Ihering, with whom the reader is well acquainted by now, was one of the principal opponents of the “dogmatism” of the Pandectists.15 Despite having devoted a good part of his academic life to Roman law scholarship, von Ihering objected to concepts, principles, and even rules devoid of a socio-economic purpose and context. In von Ihering’s view, the main contribution of law to society stemmed from its ability to harmonize the social and individual interests at stake in judicial disputes and proposed legislation, and when that was not possible, to choose among them. The function of the law, as he saw it, was not to build abstract, permanent and symmetrical structures of rights and duties, but to find the right solution to these conflicts and thereby do justice.16

Pandectism did not deal adequately with issues of justice because it was only tangentially interested in the facts and interests at stake in legal disputes or in law-making processes. Its interest was in “abstract” inquiries such as whether rights in rem or in personam (as with typified contracts) are limited or unlimited in number. Hence, its ultimate goal was to formulate concepts, rules or principles loyal to Roman law and to logical legal symmetry.

Even though the German Civil Code ) (BGB) was enacted in 1900, three years after the enactment of the German Commercial Code (Handelsgesetzbuch of 1897 HGB), I will discuss the drafting of the BGB first because decades prior to its enactment there was a legislative attempt to harmonize it with the existing version of the HGB. As will be discussed below, in 1857, the lower house of the German parliament (the Diet) designated a commission of lawyers and businessmen to draft a general commercial law.17 The approved version of this law, the Allgemeines Deutsches Handelsgesetzbuch, (hereinafter ADHGB), became the federal commercial law of the entire new German Reich in 1871.18 However, its absorption by the BGB became one of 414the major issues during its drafting. This issue was resolved in favor of harmonizing the ADHGB with the BGB.19 From the inception of the HGB, then, a close, if not organic, connection with the BGB was taken for granted. The BGB eventually provided many rules and principles to fill in the numerous gaps in the HGB.

This harmonization had to take into account that prior to Germany’s unification and the creation of its “Second Empire” in 1871, four main systems of civil law were in force: the received Roman common law (das gemeine Recht),20 the Prussian General Land Law of 1794 (Preussiches Allgemeines Landrecht),21 the Code Civil of 180422 and the Saxon Code of 1863.23 Once its federal government was empowered to promulgate a code that would govern most aspects of Germany’s private law in 1874, a legislative pre-commission was placed in charge of appointing the drafters of the future BGB.24 It appointed eleven drafters comprised of six appellate judges, three government officials and two law professors.25

This drafting commission decided that the civil code should be divided into five parts, beginning with a “general” part. This method was consistent with Puchta’s pyramidal or “from the more general to the more specific” approach on how to best organize and summarize Germany’s private law. “[T]he commission assigned each of the five major parts of the proposed code to one of its members.”26 It met during the following thirteen years and completed its first draft in 1887.27

Serious objections were voiced against its drafting technique, complaining that it was too abstract, confusing, and crowded with cross references, and thus written only for highly trained lawyers and not for the people.28 In response to these and other objections, including the lack of attention to the needs of the poor,29 a second drafting commission was appointed in 1890. This commission consisted of twenty-two members: 415ten were lawyers, judges, or law professors, and the other twelve were laymen; the latter were to be consulted on special questions.30

Although this group had the appearance of a pluralistic sub-commission, its members were mostly from the business sector: owners of large farms, a bank director, a director of a brewery, a professor of economics and a professor of law.31 This second commission produced a new draft, including changes prompted by the previously-mentioned objections. Yet, as concluded by Von Mehren and Gordley, while this draft attempted to adapt to the needs of German society and recognize issues of social justice, the language was “not generally rewritten; the number of cross-references was reduced. However, its basic structure was not changed.”32 I would only add that the presence of the business sector in the drafting committee was responsible for the greater sensitivity to the importance of commercial contracts and their inclusion in the code. It was sent to the legislature in 1895 after adding changes on the law of associations, family, successions, and tort law. Finally, a third draft was approved on July 1, 1896 and signed by the Kaiser on August 18 of that year. Its date of effectiveness was January 1, 1900.33 Its adoption as a model for other civil law countries, while not as widespread as that of the Code Civil, was nonetheless impressive. At last count, the following civil law countries used it as a model for their civil codes: Estonia, Greece, Japan, Latvia, People’s Republic of China, Portugal, South Korea, Thailand, and Ukraine.

It will be recalled that the Code Civil was divided into books on persons, things and methods of acquiring property. Each of these books covered a different and purportedly self-contained subject of private law, much as was done by Justinian’s and Gaius’ Institutes. The BGB was also divided into books, but its first book was labeled a general part and was followed by books on obligations, property, family law and successions.

Because the BGB devotes a separate book to persons, one might be tempted to assume that when it named its first book “General Part,” it was just renaming the materials covered by the Code Civil’s first book on persons. This was not the case. After providing both principles and detailed rules on the subject of physical and legal persons or associations, the general part of the BGB provides the general principles and the nomenclature for the law of things, legal transactions, time limits and statutes of limitations, exercise of rights (including self-help), and security interests.

It is also noteworthy that unlike the Code Civil, the BGB, in the first section of the general part, deals with both civil, not-for-profit (non-economic) associations and for profit (economic) associations.34 And even though it did not regulate the latter in detail, it provided key principles such as the need for a state grant for economic associations 416to enjoy a separate legal personality in the absence of special provisions.35 Similarly, it set forth the principles and rules that govern the determination of the location or seat of these associations as well as their creation, representation, and management.36

The second section of the general part provides the basic concepts and principles for things whose more detailed regulation is found in the BGB’s Book 3 on Property. Hence, “corporeal objects are things in the legal sense”37 and the basic features of fungibles, consumer goods, component parts, fixtures, accessories, fruits, and so on are set forth in the code.38

The BGB originally consisted of 2,385 sections, 800 of which had been modified during its first century of existence.39 Many of these changes were enacted during the Nazi era and subsequently abrogated during the military occupation following the Second World War. Most of the changes took place in family and obligations law.40 However, the latter was revisited during the new millennium, and in January of 2002, a very substantial reform of the law of obligations (Schuldrechtsreformgesetz) became effective.41

One of the concepts that inspired the third section of the general part (on legal transactions) was the “juridical act” (Rechtsgeschäft). It was not defined in the BGB, although, as suggested in jest by F. H. Lawson, this definition was probably reserved for post-BGB Pandectists.42 To this remark, he added, also in jest, that he did not know whether the juristic act was “a true conquest of the human mind or an aberration.”43

In connection with the meaning and purpose of the juristic act, Professor Riegert asked: “What do offer, notice of rescission, and consent to adoption have in common?”44 One could have added to this list: executory promises of all types (which are less conditional than offers), notices of terminations of tenancies, a grant of authority to an agent, the making of a will, etc. The drafters of the BGB assumed that these acts had in common the embodiment of a juristic act or an act to which the legal order attached consequences even though a contract was not required for such an act to be binding. As stated by E. J. Cohn, the concept of a Rechtsgeschäft is wider than that of a contract or even that of an agreement; it includes acts in which one party promises or states something that the law deems binding or of legal relevance.45 An analogy to a precision watch comes to mind—one central part or mechanism that acts as the prime mover for all of the others to follow. In addition, please notice the peculiar meaning of empiricism 417in the drafters’ attempt to find a common denominator of all acts and promises that could be binding.

The Pandectist origins of this concept are apparent. One only has to reformulate Professor Riegert’s question in a Pandectist fashion and the answer will become redundantly self-evident: To what manifestations of the human will (whether expressed by one or more persons) does the private law (especially in the Corpus Juris Civilis and gemeines Recht) attach binding or coercive consequences? A number of such manifestations will be found, and the next “scientific” question will be: What do these manifestations have in common? The inevitable answer will then be: They all are juristic or legal acts or transactions for which the law provides binding or coercive effects to acts or promises by members of German trading society.

How helpful is this analysis? The Pandectist would claim that having identified the common elements of the manifestations of the will to be bound, it will be possible to build an analytical system of code drafting and interpretation. Fewer rules would be necessary than if each possible manifestation were regulated and uncertainty and normative gaps were eliminated. The general principle that guides such manifestations will justify or reject the application of a specific rule to the facts in question. Thus, the interpreter will find it much easier to determine which manifestation of the human will is binding and which is unenforceable, regardless of its label or its location in the BGB. The judge, the arbiter, and the lawyers for the parties engaged in legal transactions will always be able to look for the common element(s) of these manifestations of the will and render an exact and true opinion on the enforcement of the transaction(s) in question.

Still, how helpful is it to be told that any manifestation of the will that the law deems binding or coercive is binding or coercive, and that the reason for such a binding effect is because, in a perfectly positivistic mood, the law says so? Clearly, the BGB Pandectists shared the same attraction to circular definitions as the neo-scholastics who drafted much of the Code Civil. In addition, they were also attracted by closed numbers of exclusionary rules. Professor Phillip Heck, a von Ihering disciple, pointed to the damaging consequences of one such exclusionary rule.46

As stated by Article 305 of the original BGB, “[f]or the creation of an obligation by a juristic act, and for any alteration of the substance of an obligation, a contract between the parties is necessary, unless otherwise provided by law.”47 As noted by Heck, a contract was necessary even when it was established that the person making the unilateral expression of intent was doing so with the intent of obligating himself, and when the person to whom this intent was expressed had, “in good faith, relied upon the existence of an obligation and could reasonably so rely.”48 Heck continued:

The contractual requirement (Vertragszwang) of the BGB stands in contradiction to two protective ideas that are decisive in modern law, the protection of private autonomy and of reliance…. What opposing interests are there which can justify such infringement of private autonomy and of the reliance interest? Actually, such opposing interests do not exist…. We have 418in the contractual requirement a remnant of the older law, which limited the parties to the use of typical forms.49

The general part of the BGB, which Franz Wieacker suggests also includes Book Two, is characteristic of the Pandectist drafting style. In Wieacker’s words:

Whereas the Prussian ALR portrayed rights and duties with a broad brush in concrete situations … the BGB “factors out” the common conceptual elements in different legal relationships and places them in two General Parts (Book One; Book Two, §§ 241–432).50

Thus, in its attempt to attain a gapless normative system, the BGB often winds up sending the interpreter through the length, height and breadth of Puchta’s conceptual pyramid. Von Mehren and Gordley give the example of the search for a buyer’s remedies in connection with a recently purchased cow that becomes sick upon its acquisition. The buyer of the cow would have to consult five distinct parts of the BGB before being able to determine his remedies.51 Even a less factually-circumscribed inquiry presents similar problems. As pointed out by Wieacker:

[I]n order to find the rules applicable to sale, which is after all a common enough occurrence, one must look to four different sets of norms: to the General Part (§§ 116 ff.; 145 ff.), the general provisions on obligations (such as § 275), the general provisions on contractual obligations (§§ 305 ff.; e.g. 323); and finally the provisions on the contract of sale itself (§ 433 ff.; e.g. § 446).52

Wieacker’s conclusion is that while the General Part “bespeaks a high degree of conceptual and systematic discipline … the fact is that it fails to produce that intellectual economy and harmonious clarity which are the hallmark of successful legislation.”53 A similar assessment is shared by many, though not all, von Ihering-influenced scholars.54

On the other hand, as Wieacker also points out, another component of the BGB—its general clauses—are “[a] better way of avoiding the twin pitfalls of colourless abstraction and clumsy detail….”55 These clauses are:

[G]uidelines in the form of maxims addressed to the judge, [and] designed both to control and to liberate him. They constitute a striking and welcome concession by the textual positivists to the judges’ sense of responsibility and to a higher social morality; here the legislator was following the example of the Roman praetor, who could instruct the judex to make his decision on the basis of what was required by bona fides or good faith. By such notions as Treu und Glauben [good faith], moral conduct, general practice, serious 419reason, proportionality, and so on the draftsmen were able to render their work more durable and more adaptable to the coming turmoil than they could have realized.56

Much of the ideological inspiration for the BGB came from the National Liberal Party, the dominant party in the 1871 parliament (Reichstag).57 In response to the forces described in the previous chapter,58 the liberals wanted to legislate, inter alia, on land law, family law and on the law of associations (civil and commercial). With this in mind, they obtained a crucial amendment to Article 4, Number 13 of the Law of December 20, 1873 which assigned to the future BGB the power to govern all of Germany’s private law. This power included contracts emerging from the commercialized agriculture (also described by Professor Blackbourn) and an increased ability to sell land as well as mortgages and other charges or security interests in it.59 Consistent with the encouragement of the commercialization of real and personal property, the ownership of personal or moveable property being transformed or worked upon was given to the person who transformed or worked on it rather than to the previous owner of original property.60

Wieacker dislikes this rule and calls it “nothing but an irritant in the relationship between manufacturer, financier, and supplier of materials on credit.”61 Yet, if the processor was a worker, artisan or craftsman, a rule that had conferred upon him pledgeable rights in the products he processed was bound to be helpful in a credit system that required that the borrower be the owner of the asset he pledged.

What are the effects of the priority granted to the crafsman vis a vis third parties? There might be other lenders or other bona fide purchasers of the goods manufactured as a result of the contribution of labor to the completed goods. Which rule protects the market better?

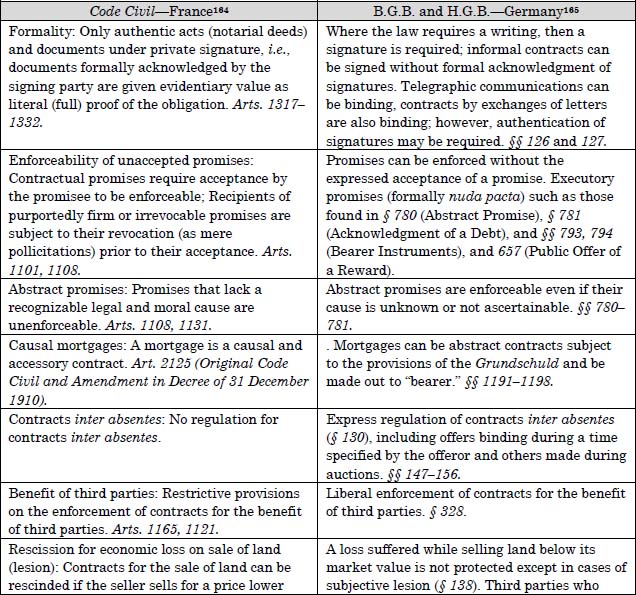

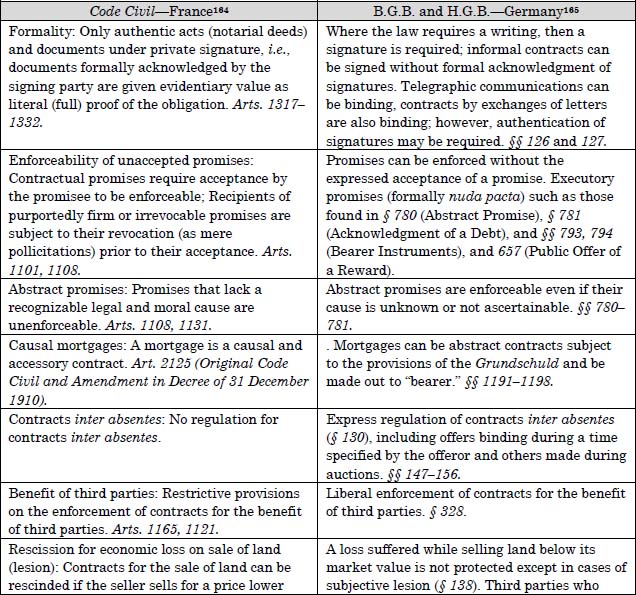

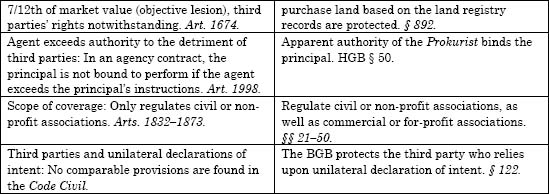

The BGB helped to commercialize many of the theretofore “civil” (or not-for-profit) transactions. Had the same transactions been governed by the Code Civil, they would have been subject to a more restrictive, if not crippling, regulation. For example, the BGB did not declare illegal the Roman Pactum Commissorium (as was done by the Code Civil and its progeny) whereby creditors could repossess, retain, or resell property pledged or mortgaged. As discussed earlier, unlike the Code Civil, the BGB governed a number of aspects of for profit (economic) associations as well as not-for-profit (civil) associations.62 It also liberally enforced contracts for the benefit of third parties and 420simplified claims by the third party beneficiaries.63 In contrast with the Code Civil, the BGB regulated offers and acceptances inter absentes, typical in commercial transactions, including offers binding during a time specified by the offeror and others made during auctions.64 It made certain oral offers binding upon the offeree as well as the offeror under specified circumstances.65 The BGB also included several executory promises that could be enforced without the express acceptance of the promisee. Among such are: abstract promises;66 the acknowledgment of a debt;67 obligations in bearer instruments;68 and the public offer of a reward.69 Furthermore, it enforced “abstract” promises or obligations regardless of the underlying transaction or its cause, thereby deemphasizing, if not doing away with, the requirement of causa.70 The abstraction or separation of conveyances and assignments from their causa enabled the negotiation of charges and security interests on land by means of transferable and bearer paper.71 I should add that this feature of German mortgages and land charges has yet to be attained by a number of countries whose civil codes have followed the “causal” model of the Code Civil. For similar market-protection reasons, the BGB rejected the Code Civil’s rescission of sales of real property when the seller suffered a laesio enormis.72

While the BGB contained considerable scholastic conceptualism and its application to everyday life was often questionable, it also provided many wise and practical rules that encouraged the entrepreneurial spirit prevalent in Germany at the end of the nineteenth century. It did this, principally, by granting enhanced negotiating freedom to contracting parties and by protecting the buyers of both real and personal property as well as creditors who relied on the security of such property. While its impact upon scholarship and code drafting in other civil law jurisdictions has been exceeded by the Code Civil,73 its impact upon economic development has been much greater, especially because of its closer and supporting relationship with the HGB.

The HGB was not a product of Pandektenrecht. The “spirit” of the HGB can be found in a seminal and early nineteenth-century commercial statute whose method of drafting and key features differed sharply from those of its French counterparts as well as from the BGB.

While the content and methodology of the proposed national codification was being debated by legal scholars, Germany started its attempts at commercial legal uniformity. The first attempt dated back to the 1830s and involved bills of exchange. As was discussed in the previous chapter, these were the same instruments whose use by non-merchants had troubled Napoleon. Yet, as noted by Dr. Karl Einert’s 1839 influential monograph,74 by the middle of the eighteenth century, bills of exchange and promissory notes were being used not only as a means of payment of commercial obligations, but also as devices with which to provide credit to merchants and governments in England and Germany. The ultimate providers of this credit were third parties to the underlying transactions who, as purchasers in good faith of these instruments (also known as “holders in due course,” “holders in good faith,” or “protected holders”), enjoyed a higher degree of legal protection than did their predecessors, the original parties to those very same instruments.

Henry Diedrich Jencken, whose important comparison of early European negotiable instruments law we studied in the preceding chapter, referred to the common conviction of the confederate German states to adopt a uniform or general law of bills of exchange (Allgemeine Deutsche Wechselordnung); what was at stake was the health of “the commercial and financial intercourse of Germany.”75 This was a wise conviction because as just pointed out bills of exchange were being used in Germany and neighboring countries as instruments of payment and credit. In the latter capacity, they provided financing to governments, banks and merchants, including agricultural, railroad and construction businesses. It is therefore not surprising that in 1847, when the Cabinet of the Confederate States of Germany sitting in Berlin invited all the member states to participate in a conference to draft a uniform law of bills of exchange, most participated. It started its sessions in Leipzig on December 9, 1847 and finished (after 35 drafting sessions) in May 1849 by promulgating what became known as the Law of Bills of Exchange (Wechselgesetz).76

The Einert-inspired Wechselgesetz remained in force only for a short period of time because of the collapse of the National Assembly of Confederate German States. Nevertheless, within fifteen years of this collapse, the individual states promulgated this same law as part of their own law. In 1871, as a result of Germany’s final unification, it became a national statute and as such remained in effect without major changes until 1933 when it was replaced by Germany’s adoption of the Geneva Convention on Bills of Exchange and Promissory Notes. Nonetheless, the Wechselgesetz was adopted as a national or provincial negotiable instrument law by Austria, Finland, Serbia, Sweden and the Swiss cantons.77 It also influenced the English Bills of Exchange Act of 188278 and the United States Uniform Negotiable Instruments Act of 4221896.79 The reader is encouraged to refresh his or her memory by revisiting the preceding chapter’s comparison of the French and German laws of bills of exchange and to reflect on the reasons for the common features in German, English and subsequently United States law. Could at least one of these reasons be a growing common commercial culture?

In 1857, the lower house of the transitional German parliament (the Diet) designated a commission of lawyers and businessmen to draft a general commercial law.80 In 1871, it approved the final version of the General Code of Laws Relative to Commerce (Allgemeines Deutsches Handelsgesetzbuch (ADHGB)).81 The purpose of this rather brief code was to guide those it identified as merchants on their rights and obligations in key commercial transactions and on their duties to the local and future national authorities. These duties included the merchants’ registration of their business associations, commercial names and marks, and their proper keeping of accounting books and records. In return, they had the right to use their names exclusively and rely on their records as evidence in disputes with other merchants and non-merchants. Because the Diet lacked the power to enact national legislation, it recommended passage of this statute by each individual state. Finally, in 1871, the ADHGB became the federal commercial law of the entire new German Reich.82

Once the BGB was on the drawing table, one of the major issues was whether it would absorb the ADHGB and become the private law code of Germany. This issue was resolved by harmonizing the ADHGB with the BGB, eliminating contradictions and redundancies between the two codes, but leaving in force those texts that were compatible in both. Accordingly, a partly-commercialized BGB became effective January 1, 190083 and a harmonized and amended ADHGB was enacted as the HGB in 1897 and became effective in 1901. Its text, enlarged by numerous and continuously incorporated amendments, remains in effect today.84

In marked contrast with the BGB, the HGB was largely drafted for merchants and thus it has an easily understandable and close-to-the-marketplace style. Yet, what it gained in clarity, it often lost in precision. In the words of one of its translators:

[W]hereas in the BGB the same concept is almost always described in identical words … in the HGB this is not always the case. On the other hand, the language of the HGB can be described as rather simpler, less convoluted and less impenetrable than the language of the BGB.85

Typical of the HGB drafting style were its provisions on a firm name:

§ 17 [Concept]

(1) The firm name of a merchant is the name under which he carries on his business and gives his signature

(2) A merchant can sue and be sued in his firm name.86

§ 18 [Firm name of sole merchant]

(1) A merchant who conducts his business without a partner or only with a silent partner must use his family name with at least one of his Christian names fully written out as first name….87

To determine its scope, the HGB first established the status of merchants and did so based upon the businesses or enterprises they were engaged in.88 As stated by Section 1(1) of the HGB: “A merchant within the meaning of this Code is a person who carries on a commercial enterprise.”89

It is worth emphasizing that the listing of the transactions in the HGB, unlike that of the Code de Commerce, had the purpose of making those who habitually practiced the listed transactions automatically eligible for the status of merchants. The HGB conferred such a status and its privileges unhesitatingly, unlike the Code de Commerce, whose conferral was hesitant and fearful of the accusation that the drafters ignored the equality of treatment of all French citizens. Thus, while the policy of the Code de Commerce did have a predominantly choice-of-law purpose by making sure that its law applied as little as possible to non-merchants, the HGB cared much less if it applied to non-merchants. Whoever carried on a business was entitled to its privileges and subject to its duties. Once one realizes the differences between these two legislative policies, one also realizes that the longstanding objective-subjective dichotomy relies on the fallacious assumption that both had the same purpose, i.e., to determine when commercial law is the applicable law.

The objective-subjective dichotomy has, indeed, been regarded as the touchstone for the application of commercial law by generations of law professors, especially in France, Spain and Latin America.90 It assumes that, depending upon whether the commercial code is of an objective or subjective nature, some disputes will be governed by the commercial code and others by the civil code. Accordingly, if the dispute involves acts which are not part of the list of acts of commerce of the Code de Commerce, the applicable law will be the Code Civil. Similarly, if the dispute does not involve a merchant as defined by the HGB, it will be governed by the BGB as the counterpart to the Code Civil.

In addition to assigning to it the same choice-of-law purpose, those who affirm the existence of this dichotomy for choice-of-law purposes assume that commercial and civil law each possess peculiar and unchanging qualities. For lack of a better term, I will refer to one of these qualities as “civility” and will attribute this quality mainly to the Code Civil. It denotes the presence of, among others: non-profit-making transactions, entered into sporadically inter praesentes (as contrasted with the inter absentes feature of many commercial transactions); a concern with the protection of bourgeois landowners; a preference for contractual causa and for notarial formalities; and only a modicum concern for the rights of third parties.91

The polar opposite of the quality of civility is supposed to be the commerciality of the transactions regulated by the Code de Commerce and its progeny. Its transactions are all motivated by profit making; they are generally standardized and carried out in large numbers, and they are mostly informal and often inter absentes. Causa still plays a role in these transactions, especially when it is immoral or illegal, and seeks to protect the rights of third parties, but the degree of protection varies with the type of commercial code involved. For example, in addition to the less-protected status of a holder in due course of a French bill of exchange discussed in the preceding chapter,92 those who relied on the authority conferred upon holders of powers of attorney issued by French merchants under the original regime of the Code Civil and Code de Commerce were less protected than those who relied on a Prokura governed by the HGB.93

Yet, as discussed in the preceding section, the BGB absorbed many commercial provisions originally intended for Germany’s first General Code of Commercial Laws (ADHGB). This absorption made the BGB a much more commercial code than was the Code Civil. Hence, the consequences of applying the BGB to a transaction involving a non-merchant could be much more “commercial” than they would be if the applicable code were the Code Civil and its progeny.

For example, the BGB enforced “abstract” promises, i.e., promises binding merely because as stated by Section 780, the promise itself creates the obligation (regardless of the underlying reason or cause of such a promise).94 Not surprisingly, and in contrast with the BGB, the Code Civil and its progeny enforced only those promises whose issuance was supported by a morally- and legally-valid causa.95 As was apparent in the discussion of the business of the House of Rothschild,96 abstract promises for the payment of sums of money or for the future delivery of investment securities or commodities had become key legal elements of the global financial marketplace. This abstraction became possible in the HGB and in the BGB because their drafters, unlike the drafters of the Code Civil and Code de Commerce, did not require a legally- and 425morally-valid causal connection between monetary promises and their underlying causes.

Clearly, the Code Civil and the BGB had different legislative goals and levels of civility and commerciality. The different legislative goals of the Code de Commerce and the HGB, as well as their discrepancies, rendered the objective-subjective dichotomy questionable. For if the HGB’s goal was to provide an inclusive legal umbrella for German merchants, big and small, to do whatever the marketplace regarded as business, it had little in common when it came to policy with the Code de Commerce, whose goal was to make sure that only those who performed its short, but in principle exhaustive list of acts of commerce that came under its umbrella. In that light, whether a given transaction was an essentially civil or commercial act was subordinate to the inclusionary or exclusionary goals of the respective codes. Thus, such questions do not belong at the forefront of commercial legal research. At best, they are scholastic exercises that offer no valid reasons in favor of or against unifying our contemporary private law. For this is a law inhabited preponderantly by commercial transactions and by commercialized versions of Code Civil, Roman-law-inspired versions of transactions such as sales (emptio venditio), agency (mandatum) partnerships (societas) and loans of things and money (commodatum and mutuum), whose adaptability to present day commerce has been and will be shown to be impracticable. On the other hand, whether a unification of the law that governs commercial and formerly civil transactions is possible and functional has been proven by the Swiss Code of Obligations of 1911 and the Italian Civil Code of 1942 and, to a more limited extent, by the U.C.C.

Consider, for example, the following sections extracted from the Table of Contents of the Swiss Code of Obligations of 1911 and notice how contracts regarded traditionally as “essentially civil,” such as that of a donation or of sale of real property, became part of the same code and were regulated side by side with “essentially commercial” contracts such as residential and commercial leases. In addition, notice how consumer protection provisions, also housed in the same code, protect residential and commercial lessees from abusive practices:

Division Two: Types of Contractual Relationship

Title Six: Sale and Exchange

Section One: General Provisions

Section Two: The Chattel State

Section Three: Sale of Immovable Property

Section Four: Special Types of Sale

Section Five: Contract of Exchange

Title Seven: Gifts

Title Eight: The Lease (Formerly civil and commercial)

Section One: General Provisions

Section Two: Protection against Unfair Rents or other Unfair Claims by the Landlord in respect of Leases of Residential and Commercial Premises.97

Similarly, the Italian Civil Code of 1942 includes in the unified Book Four on Obligations, Title III (Individual Contracts), transactions regarded traditionally as “essentially” civil and commercial such as:

Sales of Immovable Property

Agency (Including a Presumption of Profit making)

(Chapter IX, Section 1) Deposit or Bailment (Formerly civil, but now including a Presumption of Non Profit)

(Chapter XII, Section I) Credit Accounts (Commercial)

(Chapter XVI, Section III) Banking Contracts (Commercial)

(Chapter XVIII, Sections I and Following) Perpetual Annuity (Formerly civil now commercial)

(Chapter XIX, Sections I and Following) Life Annuity (Commercial)

(Chapter XX, Sections I and following) Insurance (Commercial)98

To this day, no major disruptions of either Swiss or Italian private law have been reported as a result of having unified their law of obligations. In fact, following the fall of fascism, Italian legislators had the opportunity to abrogate the unified arrangement and chose not to do so. What I believe these legislative experiences teach us is that when the unified codes protect non-merchants from the exploitation of the superior expertise or bargaining power of merchants, or when they delegate this protection to other statutes such as for the protection of consumers, they provide a degree of certainty of applicable law that is missing in the objective-subjective, commercial-civil code dichotomies. I will come back to this question when we discuss the scope of the U.C.C. and the various methods of commercial contract interpretation.99

The original version of Section 1 of the HGB, defined a merchant as follows:

§ 1 [Merchant by virtue of type of business]

(1) A merchant within the meaning of this Code is a person who carries on a commercial enterprise.

(2) Every business enterprise, which has as its objective one of the kinds of business indicated below, is deemed a commercial enterprise:

1. The acquisition and resale of movable things (merchandise) or of securities, without distinction as to whether the merchandise is resold unchanged, or after treatment or processing;

2. The acceptance for treatment or processing of merchandise for others, provided that the enterprise is not carried on as an artisan one;

3. The underwriting of insurance in exchange for premiums;

4. Banking and currency exchange transactions;

5. Undertakings for the maritime transportation of goods or passengers, the business of carriers or establishments for the transportation of persons overland or on the inland waterways, as well as the business of towing barges;

6. The business of factor[ing], forwarding agent, or warehouse keeper;

7. The business of commercial agent or broker;

8. Publishing as well as other businesses engaged in the book or art trade;

9. The printing trade, provided the enterprise is not carried on as an artisan one.100

It is important to note that someone who did not practice one of the listed businesses, such as an artisan printer not falling under subsection 9, could still enjoy the important protection of, for example, the exclusive use of his firm’s name by filing this name with the Commercial Register. Up until that filing, he was unprotected because, having failed to qualify for an ipso facto status, he was not deemed a merchant. After he filed “according to the provisions in effect for the registration of commercial firms,”101 he was deemed a merchant and his commercial firm’s name was protected.

Having a registered firm name was important not only because of the business’s ability to prevent competitors from using its established and valuable name, but also because it increased a merchant’s credibility in court and among actual and potential lenders or investors. Those who were typified as Section 1 merchants were “automatically” deemed so by virtue of their type of business.102 Their registration was merely “declarative,” i.e., they had the preexisting right to be protected as merchants and the registration merely recognized the existence of these rights.103

In contrast, those not typified as merchants, such as the above-mentioned artisans or those engaged in agriculture and forestry, could qualify as merchants only by virtue 428of their registration in the Commercial Register.104 In their case, their registration was “constitutive” of rights from the time it was granted to the registrants, at which time these rights could be enforced.105 An additional constitutive right granted to non-Section 1 merchants by their registration as merchants was their ability to convey powers and commercial authority to Prokurists. As stated by the original Section 49(1), when a commercial establishment conferred the power to sign in its name (Prokura), it “authorize[d] juridical and extra-juridical acts and legal transactions, of all kinds, which are involved in the conduct of a commercial enterprise.”106 And, as made clear by the original Section 50(1): “A limitation in the scope of the signing power is ineffective as against third parties.”107

As was discussed in the previous chapter,108 this “abstract” or non-causal approach of the Prokura protected those who relied on the appearance of commercial authority of the Prokurist and thus encouraged the contracts between these third parties and the frequently unknown or distant principals (acting through their presumably authorized agents or intermediaries). As will become apparent in our discussion of agencies and powers of attorney in jurisdictions that adopted the French and Spanish “causal” (as opposed to the German “abstract”) approach to dealings with agents and holders of powers of attorney, the reliance by third parties on the appearance of commercial authority is rendered much more perilous.109

With respect to small merchants, Section 4(1) of the original HGB provided that: “The provisions concerning firms, commercial books and authority to sign shall not apply to persons the nature or scope of whose trade does not require a business enterprise equipped in the manner of a commercial business.”110

Since its enactment, the HGB has undergone a number of amendments. The most substantial of these took place in 1998, especially with respect to its scope.111 Section 1 of the 1998 amendment now states in an open number (numerus apertus) and thus contrasting fashion with the exhaustive listing of the acts of commerce by the Code de Commerce: “A merchant within the meaning of this Code is one who conducts a business.”112 In turn, subsection 2 of the same section defined a merchant’s business as: “[E]very commercial operation unless the enterprise by type and volume does not require a commercially organized business operation.”113

This was indeed an open-ended definition, in contrast with the partially closed-ended definition of the 1897 text. In that text, and as just mentioned, only those types of businesses (not mere individualized acts of commerce) listed and described could 429characterize the person or entity that carried them out as a merchant. However, keep in mind that it was only a partially closed list because, say, an artisan’s registration of his trade mark or copyright in the commercial registry entitled him to the protection of his intellectual property and to do his business as a merchant.

That the original Section 1 was drafted in the nineteenth century can hardly be missed. For example, while its subparagraph 2, subsection 5 includes the business of maritime overland and inland waterways transportation of goods or passengers and even that of towing barges, it does not mention air transportation. In addition, it left out what Dr. Martin Peltzer and Elizabeth A. Voight, two code annotators and translators, describe as “many service industries which in the meantime had become increasingly important [such as] … cinemas, theatres, schools, hotels, advertising [and] … the entire construction business.”114

The 1998 amendment of Section 1 had to take these new businesses and other marketplace facts into account. Wisely, it decided not to engage in a numerus clausus exercise by eliminating the list contained in the subparagraph 2 of Section 1. Now “anyone conducting a business is a merchant regardless of his field of commercial activity, be it production, trade, or services.”115

As pointed out by Peltzer and Voight, there are two exceptions to the applicability of the HGB to those engaged in profit-making transactions. One is guild-like in that it involves the activities of professionals such as lawyers, notaries, and physicians, among others. The other is a remnant of the 1897 system: Where a business is so small that it need not be organized in a formal manner, the person or persons involved in such a business are not deemed merchants. Nonetheless, these small merchants are allowed to apply for registration in the commercial register and, upon registration, they become registered merchants.116 Peltzer and Voight summarize the amended scope provisions as follows:

[Now] [a]nyone conducting a business is a merchant, be he registered or not. The revised Commercial Code applies to him. The merchant has a duty to register and can be compelled to file for registration by a coercive fine (§ 14 Commercial Code). Members of the professions do not carry on a commercial business, and, therefore, the Commercial Code does not apply to them. The very small business is exempted from the application of the Commercial Code, but it can file for registration and thereby become a merchant (§ 2 Commercial Code) … Agriculture and forestry are also exempted, but can likewise file for registration in the commercial register where a commercially organized business operation is required …117

These authors raise the question of why small merchants or members of civil law associations would want to file for registration and be subject to the commercial code regime. After all, this regime frequently imposes harsher obligations and stricter duties of diligence on merchants than those applicable to non-merchants under the BGB or other enactments. For example, oral guarantees made by merchants as well as other informal promises are more likely to be enforced against them than when made 430by non-merchants.118 Similarly, buyer-merchants, unlike non-merchants, have the duty to examine goods bought by them for defects immediately upon their delivery.119 Additionally, some types of merchants are deemed to have accepted offers even though they merely remained silent after receipt of these offers.120

The reason for the choice of a commercial status under the HGB lies in the considerable benefits that the application of the commercial code brings to borderline or occasional merchants, for example, a “clearly defined and undisputable limitation of liability for the limited partner of a limited partnership.”121 To these benefits, I would add: easier access to commercial intermediaries and commercial credit, and greater credibility of books and records, whether in judicial or extrajudicial procedures.

As with the Code de Commerce, the HGB sets forth in Book One the qualifications for the status of a merchant, the requirements for conducting a commercial business, and the key features of the relationship between merchants and their assistants or auxiliaries. Accordingly, Sections 1 through 58 delineate the rules that govern the existence of a business, its notice to the public, and its bookkeeping and personnel: Merchants,123 Commercial Register,124 Commercial Firm Name,125 Business Books and Records,126 Commercial Agency (Prokura) and Power of Attorney.127 Thereafter, it 431governs the status of Commercial Clerks and Commercial Apprentices,128 Commercial Agents129 and Commercial Brokers.130

What follows is a short description of illustrative sections in Book One and some of the following books.

Chapter Seven of Book One is devoted to the “commercial agent” (Handelsvertreter). Its uncharacteristically casuistic regulation reflects the myriad of activities performed by commercial agents throughout the European Union. Accordingly, Section 84 defines this agent as one:

(1) who, as an independent person engaged in business, is regularly authorized to solicit business for another entrepreneur (the “principal”) [unternehmer] or to enter into transaction in his name. A person is independent if he is essentially free to structure his activity and determine his hours of work.131

The commercial agent is distinguished from an employee in the following fashion:

Any person who, without being independent within the meaning of Sub-section 1, is regularly authorized to solicit business for a principal or to enter into transactions in his name, is deemed to be an employee.132

Among the duties of a commercial agent listed by Section 86 are:

The commercial agent is obligated to make efforts towards the solicitation or conclusion of business transactions. In connection herewith he must act in the interests of the principal … He shall give the principal all necessary information, i.e. inform him immediately of every solicitation and conclusion of every transaction … He must fulfill his duties with the care of a [honest or proper] prudent merchant [ordentlichen Kaufmanns].133

In turn, the duties of the principal are set forth in equal detail by Section 86(a), among others. The principal must provide the commercial agent with all materials which are necessary for the performance of his duties, such as samples, drawings, price lists, advertising material, and terms and conditions of business.

The principal must keep the commercial agent generally informed. In particular, he must inform him promptly of the acceptance or rejection of a transaction procured by the agent or a transaction concluded by the agent without authority, and of the non-fulfillment of a transaction procured or concluded by him. He must inform him promptly if he desires, or will likely be able to, conclude transactions only on a 432significantly reduced scale in comparison to that which the agent could expect under normal circumstances.134

The same degree of detail is provided with respect to the agents’ entitlement to remuneration, its due time and its amount. The regulation takes into account factors such as the type of commercial agency and the agent’s guarantee of the fulfillment of the commissioned transaction, the right to an accounting and to the reimbursement of expenses, and the agent’s lien or right of retention for what is lawfully owed to him.135

Book Two of the revised HGB governs general, limited and silent partnerships. The distinctive features of the general partnership are: (1) its purpose—which is the operation of a commercial enterprise; (2) its form—a common firm name; and (3) its liability—no partner’s liability is limited with regard to what is owed to partnership creditors.136 As a sign of the degree of commercialization of the BGB, the HGB states that “to the extent that this section does not provide otherwise, the provisions of the Civil Code concerning partnership shall be applicable to commercial partnerships.”137

The concern with the partners’ authority to bind the partnership, especially when dealing with third parties, is apparent. After setting forth the broad scope of the partners’ powers of representation, including judicial and extrajudicial proceedings, alienation and encumbrance of real property, and conferral and revocation of a Prokura, the code states:

Any limitation of the extent of power to represent is ineffective as against third parties; this is applicable in particular to the limitation that the representation should extend only to certain transactions or kinds of transactions, or that it should be allowed only under certain circumstances or for a certain period or in particular places.138

As with the preceding books, Book Two provides a highly detailed regulation of the general commercial partnership including: the extent of the partners’ liability;139 the defenses available to them when sued for partnership debts, including the repayment of partnership loans;140 the liability of a partner joining an existing partnership;141 the dissolution of the partnership and withdrawal of partners;142 the termination of the partnership by the personal creditor of a partner;143 and continuation of the business with the heirs of a dead partner,144 concluding with its liquidation.145

As with the general partnership, the limited partnership is distinguishable by: (1) its purpose—the operation of a commercial enterprise; (2) its form—a common firm name; and (3) its liability—limited with respect to one or more partners up to the amount of their capital contributions, a limitation combined with the absence of limitation in the case of the general partners.

Many of the provisions applicable to the general partnerships also apply to the limited partnership, including the formalities of organization, bookkeeping, etc.146 One additional distinguishing feature is that limited partners are excluded from the management of the business and cannot object to actions taken by the general partners unless these actions “exceed[] the scope of the partnership’s ordinary business.”147

The key feature of the silent partnership is that the silent partner makes his capital contribution in such a manner that it is transferred directly to the assets of the owner of the business. Thus, “[t]he owner alone will have the rights and obligations arising from the transactions made in the courses of conducting business.”148 Evidently, the silent partner is more trusting than the limited partner because, in the limited partnership, the limited partner contributes to the partnership’s capital while the silent partner’s contribution is to the assets of the owner.

Reflecting this higher degree of entrustment, the method for sharing profits and losses does not have to be specified in the silent partnership agreement. Where not specified, the silent partner’s share of the profits is that which is “appropriate in the circumstances.”149 His right to profits may not be excluded even if the partnership agreement stipulates that the silent partner is not to participate in the losses.150

The provisions on record keeping in the revised HGB contain some of the most innovative provisions found in contemporary commercial codes, especially as updated for corporate governance in a June 14, 2007 amendment of the 2003 revision.151 The following are summary illustrations of what was accomplished in these two revisions. According to Section 238 of the 2003 revision, every merchant is obligated to keep books and:

Make visible his commercial transactions and the state of his assets according to the principles of orderly accounting. The accounting must be in such a condition that an expert third party can have a general insight concerning the operation of the business and concerning the state of the enterprise….”152

In addition, “[i]n the keeping of business books and other required records, the merchant shall employ a living language….”153

These principles depart radically from the nineteenth-century Spanish commercial code that required a mandatory set of books and entries, regardless of whether they reflected generally accepted accounting principles.154

Book Four governs selected commercial transactions, such as sales, commission transactions, warehousing, freight forwarding and transport of goods. The reason for including some of these provisions in the HGB rather than allowing the BGB to govern is the commercial status of the parties. For example: the time when performance can be demanded is related to the merchant obligor’s “usual business hours”;155 the stipulation of merchandise by means of generic characteristics is to be fulfilled by tendering goods of “average description and quality”;156 the computation of measure, weight, currency, time, and distance is to be made in accordance with what is customary at the location where the contract is to be fulfilled;157 the silence of a merchant offeree with respect to an offer made to him by someone with whom he has a business relationship is deemed an acceptance if the offeree does not reply immediately.158

The provisions on the contract of transportation govern exhaustively the rights and duties of the parties to inland as well as multi-modal transportation and apply to documents that are mere receipts such as truck or rail waybills, as well as to documents of title such as negotiable bills of lading.159 Negotiable instruments continue to be governed on the whole by the Geneva Convention adopted by Germany, among many other civil law countries, in 1933.160 Similarly, Book Five of the HGB, devoted to maritime law, applies the Hague-Visby rule on liability for damage to maritime cargo, both to inbound and outbound shipments.161

In contrast with the paternalistic and anachronistic proevisions of the Code de Commerce discussed in an earlier chapter,162 the HGB is a more market-sensitive code. Both its original version as well as its 1998 revision, and especially the latter, allow the market to determine who is a merchant governed by the HGB. Its so-called “subjective” nature, typical of a code written for professionals rather than for certain specified acts, has made its interaction with the BGB more effective than that between the Code Civil and the Code de Commerce. One of the key ingredients in this positive interaction is 435that of German customary law, especially as found in the standard contractual terms and conditions of the various businesses as incorporated into the so-called “general conditions of trade,” which will be addressed in the following chapter.163

The following comparison of provisions in the French and German civil codes (including one provision located in the HGB, but whose rule is consistent with BGB principles) provides the opportunity to evaluate the effects of applying their respective rules (and underlying principles) to commercial transactions, including their protection of third parties.

__________________________

1 See Wieacker, A History of Private Law, at 300–29, 334–70 (a thorough yet illuminating comparison of the views of Romanists and Germanists).

2 Von Mehren & Gordley, The Civil Law System, at 10–11 (the various reasons for this en masse reception of Roman law).

3 Id. at 61.

4 Id. at 62 (citing to a translation of Vom Beruf unsrer Zeit für Gesetzgebung und Rechtswissenschaft by A. Hayward in 1831).

5 Id.

6 Id. at 62.

7 Id. at 65.

8 Id. at 62.

9 Id. The BGB is sometimes referred to as the “Little Windscheid.” See, e.g., Robert A. Riegert, The West German Civil Code, its Origin and its Contract Provisions, 45 Tul. L Rev. 48, 59 (1970) (noting Windscheid’s influence).

10 See Glossary, “Legal Positivism.”

11 See Glossary, “Pandectists.”

12 See Glossary, “Ius Distrahendi.”

13 This incident, including the notes concerning the Registrar’s first opinion, was relayed by the late Professor Milton Katz of the Harvard Law School, one of the United States legal officials involved in the implementation of the Marshall Plan in Germany, to my friend, the late Professor Raul Cervantes Ahumada of the National University of Mexico Law School. Professor Cervantes Ahumada allowed me to copy them shortly before his death in 1994.

14 Id.

15 See Wieacker, A History of Private Law, at 355–57 (an insightful summary of von Ihering’s evolution from leading Romanist to founder of the sociological jurisprudence movement in Europe and elsewhere).

16 Von Ihering’s most coherent views on the purpose of the law can be found in his book Law as a Means to an End. See generally von Ihering, a Means to an End. Of particular interest is his analysis of the idea of justice in commerce. Id. at 101–03.

17 Von Mehren & Gordley, The Civil Law System, at 73.

18 Id. at 73–74.

19 Id. at 74.

20 Riegert, supra note 9, at 49. Riegert points out that by the end of the nineteenth century, the Roman common law still covered about 33 percent of the German population. Id.

21 Id. at 51. Riegert attributes to the Prussian Code an application that was “partly primary, partly subsidiary … over 43 percent of the German population.” Id.

22 Id. Riegert attributes to the Code Civil an application over “17 percent of the German population.”

23 Id. at 52. Riegert attributes to the Saxon Code an application over “7 percent of the German population,” although he also ascribes to it a predominant influence as “the organizational model for the BGB….” Id.

24 Von Mehren & Gordley, The Civil Law System, at 75.

25 Riegert, supra note 9, at 52.

26 Id.

27 Id.

28 See id. at 53. Riegert points out that:

Professor Windscheid, the author of what was the leading text on the Pandects, was a member of the commission and his influence on the final product was pervasive. There were charges that the 1887 draft was “Windscheid’s book with additions.” Those Germans who favored the reception of the Roman law praised the draft, while those who rejected the reception criticized it. A third group, who called for more consideration for the less privileged in society, also joined the opposition.

Id. (Citations omitted.)

29 Id. See also Von Mehren & Gordley, The Civil Law System, at 76 (referring to Otto von Gierke’s and Anton Menger’s objections based on social and public policy considerations).

30 Riegert, supra note 9, at 53.

31 Von Mehren & Gordley, The Civil Law System, at 76.

32 Id. at 77 (citation omitted).

33 Id.

34 BGB § 22 (Goren, 1994) states:

An association whose object is the carrying on of an economic enterprise acquires legal personality, in the absence of special provisions of [Federal] law, by state grant. The grant is within the competence of the [State] in whose territory the association has its seat.

35 Id.

36 Id. §§ 24–54.

37 Id. § 90.

38 Id. §§ 90–103.

39 BGB (Goren, 1994) xviii.

40 Id.

41 German Civil Code—Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, iuscomp.org, http://www.iuscomp.org/gla/statutes/BGB.htm (a German-English translation of the reforms). Some of these reforms will be discussed in the following chapter.

42 F. H. Lawson, Seminar Discussion at the University of Michigan School of Law (Fall 1959).

43 Frederick Henry Lawson, A Common Lawyer Looks at the Civil Law: Five Lectures Delivered at the University of Michigan 167 (1955).

44 Riegert, supra note 9, at 59.

45 E. J. Cohn & W. Zdzieblo, I Manual of German Law 73 (2d ed. 1968).

46 Von Mehren & Gordley, The Civil Law System, at 831 (on Phillip Heck’s criticism of § 305 of the BGB).

47 Id. at 829.

48 Id. at 830 (citing Philipp Heck, Grundriss des Schuldrechts 122 (1929)).

49 Id. at 831.

50 Wieacker, A History of Private Law, at 376 (citation omitted).

51 Von Mehren & Gordley, The Civil Law System, at 78.

52 Wieacker, A History of Private Law, at 376.

53 Id. at 377.

54 Riegert, supra note 9, at 62–65 (discussing the advantages and disadvantages of the BGB’s abstraction). It is surprising to see that Max Rheinstein, a faithful disciple and translator of Max Weber’s seminal legal sociology, lines up with the supporters of abstraction. Id. at 63–64.

55 Wieacker, A History of Private Law, at 377.

56 Id. Some of these general clauses, such as §§ 138, 157, & 242, will be transcribed in the following chapter in conjunction with their use in judicial decisions.

57 Wieacker, A History of Private Law, at 371.

58 See supra § 11:1(B).

59 Id. See also Wieacker, A History of Private Law, at 371.

60 Id. at 373. See BGB § 950 (Goren, 1994), which states in its relevant part:

A person, who by processing or transformation of one or several materials produces a new movable thing, acquires the ownership of the new thing, to the extent that the value of the processing or transformation is not substantially less than the value of the material….

61 Wieacker, A History of Private Law, at 373.

62 BGB §§ 21–79 (Goren, 1994).

63 Id. §§ 328, 330.

64 Id. §§ 130, 147–156, 158–163.

65 Id. § 295.

66 Id. § 780.

67 Id. § 781.

68 Id. §§ 793, 794.

69 Id. § 657.

70 Id. §§ 780, 781. See also Von Mehren & Gordley, The Civil Law System, at 805–11 (a good commentary on these provisions and the lack of a French counterpart).

71 Wieacker, A History of Private Law, at 382.

72 See Glossary, “Laesio Enormis or Lesion.”

73 Wieacker, A History of Private Law, at 383–85 (discussing the impact of the BGB upon legal scholarship and code drafting in Austria, China, Greece, Hungary, Japan, Latin America, Poland, Switzerland and Yugoslavia).

74 See supra § 11:2(D)(2)(b).

75 Henry Diedrich Jencken, The Codification on the Law of Bills of Exchange and Negotiable Securities in Europe and the United States, Jurisprudence, in II The Law Magazine and Review: A Quarterly Review of Jurisprudence 80 (1877) [hereinafter Jencken, Codification]

76 Id. at 81.

77 Id. at 82.

78 Bills of Exchange Act, 1882, 45 & 46 Vict. c. 61 (Eng.), available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Vict/45–46/61/contents.

79 See Uniform Negotiable Instruments Act (1896). The Uniform Negotiable Instruments Act was promulgated by the National Conference of Commissioners of Uniform State Laws in 1896 and subsequently enacted in all states in the United States.

80 Von Mehren & Gordley, The Civil Law System, at 73.

81 Id. at 73–74.

82 Id. at 84.

83 Von Mehren & Gordley, The Civil Law System, at 77.

84 Id. at 74.

85 HGB (Goren, 1998) xiii.

86 Id. § 17.

87 Id. § 18.

88 See generally Cohn & Zdzieblo, supra note 45.

89 HGB § 1(1) (Goren, 1998). But c.f. Introduction to German Law 130–31 (J. Zekoll & M. Reimann eds., 2nd ed. 2005). In this book, editors Zekoll and Reinmann separate merchants into three distinctive categories: 1) Merchants by Option; 2) Business Associations; and 3) Merchants by Appearance. It is not easy, however, to see the difference between these categories. Id.

90 See, e.g., Ripert, at 3–6 (France); Rodrigo Uría, Derecho Mercantil 5–6 (6th ed. 1968) (Spain); Roberto L. Mantilla Molina, Derecho Mercantil 8–9 (1966) (Mexico).

91 See Kozolchyk, Commercialization, at 12, 16–17, 22, 26–27.

92 See supra § 11:2(D)(2).

93 See supra § 11:2(G).

94 BGB § 780 (Goren, 1994) (“For the validity of a contract whereby an act of performance is promised in such manner that the promise itself is to create the obligation (promise of debt), a written statement of the promise is necessary, unless some other form is prescribed.”).

95 See C. Civ. (Fr.) art. 1131 (Barrister 1804) (“An obligation without a cause, or upon a false cause, or upon an unlawful cause, can have no effect.”); C.C. (Spain) art. 1275 (1889) (“Contracts without a cause, or with an unlawful cause, do not produce effects whatsoever. A cause is unlawful when it conflicts with the law or with morals.” (author’s translation)).

96 See supra § 11:4.

97 This list of contracts was extracted from the section headings of the Swiss Code of Obligations. Obligationenrecht [OR], Code des obligations [CO], Codice delle Obligazioni [CO] [Code of Obligations] Mar. 30, 1911 SR 220, RS 220 (Switz.), available at http://www.admin.ch/ch/e/rs/2/220.en.pdf.

98 Codice Civile E Leggi Complementari 513–23 (F. Carnelutti & W. Bigiavi eds., 1964) (source of this extracted list).

99 See infra ch. 22.

100 HGB § 1 (1897).

101 Id. at § 2, which states:

An artisan or like business enterprise, the carrying on of which is not deemed a commercial enterprise under § 1(2), but which according to its nature and scope requires a business establishment organized in a commercial manner, is deemed a commercial enterprise within the meaning of this Code, insofar as the firm name of the enterprise has been entered in the Commercial Register. The proprietor is obliged to effect the registration according to the provisions in effect for the registration of commercial firms.

102 See Peltzer & Voight, at 4.

103 Id.

104 See HGB § 3 (Goren, 1998).

105 Id.

106 Id. § 49(1).

107 Id. § 50(1).

108 See supra § 11:2(G).

109 See supra § 5:13(B).

110 HGB § 4(1) (Goren, 1998).

111 See Peltzer & Voight, at 1–3.

112 Id. at 35.

113 Id.

114 Id. at 3–4.

115 Id. at 4.

116 Id.

117 Id. at 4–5.

118 Id. at 5 (citing to § 350 of the German Commercial Code). Section 350 states: