Appendix

Kayin/Cain is a figure often demonised in ancient literature; some claiming he was the product of a liaison between Eve and the Devil, others that he grew horns! Why have I chosen to represent him differently? And why tackle this story at all? Besides (I believe) a prompting of the Holy Spirit, there are two main reasons:

1. I think it likely that, despite the horrendous murder, Cain was not especially evil or demonic, but rather his sin reflects the potential present in all human hearts. It is important to note that we are all capable of committing awful acts, given the right set of circumstances. Jesus implied that if we hate our brother, we are guilty of murdering him (Matthew 5:21–22). As such, my intention was to portray Kayin in a human light – as someone we could understand – and the murder not as a random act of rage but as a culmination of allowing sins (such as envy and pride) to take over our lives. That is not to excuse what he did, which is inexcusable. But let us never judge another without first examining our own hearts (Matthew 7:1-5).

2. I wished to redress an imbalance in our understanding of Cain based on the scripture rather than peculiar ideas that have been passed down the generations. To do this, I read Genesis 2–4 countless times in many different versions and considered what the whole line of Cain might look like, from Adam to Lamech’s offspring. I also considered the Bible verses where he is mentioned outside Genesis 4, as follows:

In Hebrews 11:4, it merely says Abel’s offering was more acceptable than Cain’s. In 1 John 3:11–12, Cain is described as belonging to the evil one, and given as an example of what we as Christians should not be: haters of our righteous brothers.

Jude v8–11 is the final reference regarding Cain and is worth quoting:

Yet in like manner these people also, relying on their dreams, defile the flesh, reject authority, and blaspheme the glorious ones… these people blaspheme all that they do not understand, and they are destroyed by all that they, like unreasoning animals, understand instinctively. Woe to them! For they walked in the way of Cain and abandoned themselves for the sake of gain to Balaam's error and perished in Korah's rebellion.

What does this imply about the manner of Cain’s sin, given that it was alike to the ‘ungodly people’ Jude is talking of? Jude is a complicated book, but we can glean some clues from it without getting stuck in the detail.

Firstly, the sin involves a form of blasphemy, blaspheming what is not understood, and being destroyed by carnal instincts.

Secondly, walking the way of Cain has something to do with Balaam’s error. Balaam was the prophet hired to curse Israel in Numbers Chapters 22-31. Balaam’s error was to compromise his convictions for material gain.

Lastly, it resembles Korah’s rebellion, which was when a group of Levites complained to Moses because they had not been selected for the priesthood (Numbers 16).

From all of this we can conclude that Cain was a believer (why else would he sacrifice?) albeit one who had rebelled, giving himself to the evil one, and had allowed hatred for Abel to consume him. Additionally, his sin had to do with blasphemy against God, choosing carnal desires over spiritual ones, choosing material gain over spiritual gain, and desiring a holy office that was not given him.

All these ideas are woven into my story. I cannot really take credit for this, for I must confess I had entirely missed the Jude passage until the final editing stage! When I found it, I was staggered at what I had been inspired to write, and I am supremely grateful to the Holy Spirit for the reassurance. I hope it also sets your mind at rest that my interpretation is not unbiblical.

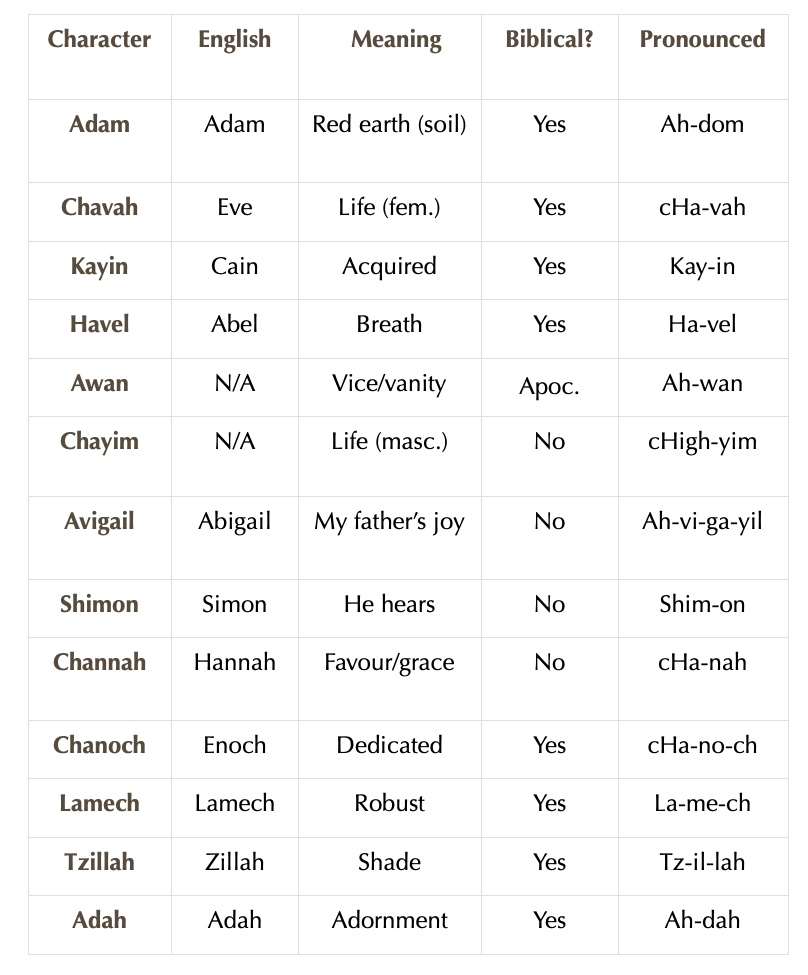

We have no way of knowing if the earliest language (never written down) was similar to ancient Hebrew – it may have been slightly or altogether different – yet it’s a reasonable guess. So, I decided to use Hebrew forms of the character names, rather than the ones we are familiar with, to give Kayin a chance to tell his story without facing immediate judgement. I hope it helped you to get alongside the characters and enter their world. The English informal names Dad/Mum were also replaced with the Hebrew Abba/Ima.

Hebrew is difficult to transliterate into English because we do not have all the same letters or sounds. For example, the sound written ‘ch’ is pronounced more like ‘ugh’ than the ‘ch’ in cheese. This sound forms the beginning of the names Chavah, Chayim and Channah. In most cases, I have transliterated the letters as closely as possible, using ancient Hebrew as my basis, not modern Hebrew. Where there were several variations of the spellings, I chose what reads most easily – to my eyes anyway. For the same reason, I left out some letters, such as the ‘y’ in Elohiym. Apologies if you are a Hebrew scholar and you disagree with me on any of the names.

For most of the story, I used variations of the Hebrew name for God, Yahweh Elohim, where Elohim represents the more formal name for God the Creator, and Yahweh, the personal name that God reveals to His people. The name of the LORD is debated, for written Hebrew did not originally include vowel sounds and the pronunciation of the letters y/j and w/v have caused confusion. Many would use the name Jehovah instead.

I chose Yahweh as it is most familiar to me. Most scholars agree that ancient Hebrew used the pronunciation waw for the modern letter vav (w for v in English), although it’s possible Yahveh might be correct. As even ancient Hebrew does not have a ‘j’ sound, I have assumed the first letter should be pronounced ‘y’. The difference in the vowels of Yahweh and Jehovah comes from the use of the vowels present in Adonai (meaning Lord/master) in place of the order in Yahweh when the name was considered too holy to say aloud. The Bible Project has some excellent videos on this if you’re confused or want to know more.

Havel also uses the name Ruach Elohim, which is the Spirit of God. Ruach literally means breath or wind. Interestingly, the word is similar in meaning to Havel, though without the connotation of shortness, or meaninglessness. (Havel/hevel is the word used in Ecclesiastes 1:2). It is Ruach Elohim who hovers over the waters in Genesis 1:2, and ruach that Elohim breaths into Adam in Genesis 2:7.

Why did I choose to use Yahweh when that name is often reserved for times post-Exodus 6 where God tells Moses that the patriarchs (Abraham, Isaac and Jacob) did not know His name? I believe it is likely that the God who walked with Adam in the Garden also revealed His holy name to the first family. In Genesis 2 (the ‘personal’ account of creation), The LORD God: Yahweh Elohim, is used. It is also used repeatedly in Gen. 4, and is particularly notable in Gen. 4:26, where people began to ‘call on the name of Yahweh’. Therefore, if the name of Yahweh was forgotten at some point before Abraham and re-revealed to Moses at the time of the Exodus, that doesn’t mean it was not used in a personal way by His followers in the most ancient times.

I did choose not to use any later names for God, though (such as Adonai). I stuck to the words used in the first few chapters of Genesis as this was the basis of my book.

Whilst the meanings of names were significant, some of them were unclear. As I built several name meanings into my character profiles, I picked the meaning that best fitted my narrative anytime there was debate. Here’s my list for those of you who might be interested:

You may have noticed that Awan’s songs and Havel’s prayers are drawn from the Old Testament scriptures and paraphrased to fit my story. Am I suggesting that Psalms from thousands of years afterwards were actually written by my made-up first worship leader, Awan? No, of course not.

And yet there is a sense in which, just as our modern-day songs and hymns draw on biblical verse, so biblical verse would have drawn on an ancient pattern of Yahweh worship, featuring phrases, picture language and theology that had been handed down through generations of worshippers since the beginning of time. So we see similar language in the ancient songs of Moses and Miriam as we do in the much later Psalms of David and Asaph, for example.

Nothing happens in a vacuum, and our LORD is wonderful, eternal and consistent in His dealings with His people throughout all generations. I like to think that the first family praised Him for that just as David and others did millennia afterwards.

For your reference, the most significant passage used for this purpose in this book was Psalm 50. Havel’s prayer at the first sacrifice and Elohim’s words to Kayin are paraphrases of Psalm 50. By using scripture, I hoped to keep the voice of the LORD authentic.

For me, writing Kayin’s story was an opportunity to explore theology through storytelling, not a historical investigation. Nevertheless, I have tried to make it realistic. Some may criticise me for allowing modern concepts or theologies to creep into the mouths of ancient people. Yet, my purpose was to explore the tale within the parameters outlined above rather than worrying about whether it happened this way, which we can never know the truth of. For this reason, I allowed myself artistic license on that front.

Many will have different opinions on the age of the earth and the historical accuracy of what we find in Genesis. I have no intention of causing arguments among Christians, who are called to love one another despite our differences. Therefore, I do not offer an opinion on the age of the earth, which is an incredibly complex debate, but leave it open to the reader’s interpretation.

That said, I personally believe there are theological consequences in adopting a narrative of human evolution.Therefore, I wished to demonstrate how it might be possible for a literal reading of Gen. ch.2-4 to fit in with what we know about history and archaeology. Where the Bible is silent (like, for example, on how many siblings Kayin and Havel had and when exactly they were born), I fill in some of the gaps to fit with my story. Where it gives us information, I have tried to stick strictly to that.

I base my farming and geographical descriptions roughly on ancient Mesopotamia, assuming that, before the flood, this would have been a quite different world. Although most scholars no longer hold objections to rain occurring before the flood, I barely mention rain due to the climate I adopted and my interpretation of the curse on the ground.

Rodinia is modern science’s name for the first super-continent (pre-tectonic plate shifts.) There is much debate about what it looked like and what parcels of land it featured. Assuming Rodinia to have been the pre-flood world, I based my map of the east on one scientific projection of Rodinia and married it with the four rivers model from Genesis 2.

As regards animal varieties and early hominoid activity, I cannot consider every issue in this story of the very first human family, but – mainly for fun – I begin to explore them.

Tanninim (plural) and tannin (sing.) is a general term used in the Hebrew bible to describe monster-like creatures that inhabited both the sea and land (e.g. Gen. 1:21, Job 7:12, Jeremiah 51:34). It is also used of serpents (e.g. Exodus 7:9) and refers to the crocodile in later times. However, it is distinct from tannim (pl.), which is Hebrew for jackals. The famous creatures described specifically in Job – leviathan and behemoth – represent a giant sea creature and land creature, respectively. I interpret them to be types of tannin.

Even if some creatures might be regarded as mythological, it is possible that during the most ancient times, man inhabited earth with some giant tanninim. They may well have been what we know of as dinosaurs and their contemporaries. All myths start somewhere and, without some kind of cohabitation, it’s unlikely that dragons and the like would have made it into so many myths – though granted, the accounts were highly embellished.

Again, my intention is not to propose one view over another. Even so, I spent some time considering the question of meat-eating before Noah’s ark. Many believe that meat-eating did not happen before the flood, according to Gen. 9:3, where God says, ‘As I gave the green plants, so now I give you everything.’ However, Gen. 3:21, 4:4 and 6:11 seem to suggest meat-eating did take place, so I wanted to give this question a fair presence.

Also, in Gen. 7:2, before He apparently allows meat-eating, God distinguishes between unclean and clean animals, telling Noah to take seven pairs of clean animals onto the ark. This is the first time this distinction is recorded in scripture, but that does not mean it was the first time God had made it. Noah then offers clean animals on the altar in Gen. 8:20. The language for ‘every creature’ in Gen. 9:3 may then refer to God removing the distinction between clean and unclean rather than between plant and animal. Interestingly, the language is similar to that in Leviticus 14, which re-establishes the forbidden unclean animals. So, the Mosaic law may have reflected the intended state of things in Gen. ch.4-9. Then we make sense of Gen. 6:11, where God says the flood was necessary because all flesh had been corrupted, particularly concerning the lifeblood mentioned in that chapter and the need to destroy all animals, not just humans.

In conclusion, I do not believe it is theologically necessary to claim that nobody ate meat before the flood. However, neither do I want to abandon the straightforward meaning of the text by suggesting that it was right to do so. Therefore, I have my original family in this story eating some ‘clean’ animals, but I leave whether this was right or wrong open to the reader’s interpretation (consider particularly the incident while hunting in the woods, Havel’s reluctance to kill his sheep, and Lamech’s family – who have entirely strayed – roasting a hog).

Wasn’t Abel’s murder premeditated?

In the NIV version of the Bible, we read, ‘Now Cain said to his brother Abel, “Let’s go out to the field.” While they were in the field, Cain attacked his brother Abel and killed him.’ (Gen. 4:8).

This suggests Abel’s murder was premeditated. However, this may be a case of a paraphrase going beyond the original text. Many translations insert the contents of Cain’s speech after the first phrase, following the Septuagint and Vulgate. However, the Masoretic text literally reads, ‘Cain spoke to his brother Abel, and while they were in the field…’, so we cannot infer from that exactly what Cain said to Abel or when he said it. That Cain requested Abel to come out to the field so that he could kill him is of course possible, but I principally followed the ESV translation when I was writing, which does not insert Cain’s speech. It reads simply, ‘Cain spoke to Abel, his brother. And when they were in the field, Cain rose up against his brother Abel and killed him.’

There is a theological doctrine, which is much debated, regarding the impassibility of God. To be impassible is to be ‘not subject to passions’. In other words, because God is immutable (He cannot change), He cannot be affected by the actions of humans or relate to them in a reactive way. Does this mean that Kayin was wrong to think he could hurt God by murdering Havel in my account? Well, Kayin was wrong about many things! However, I do portray God as reacting emotionally to Havel’s death, for the following reasons:

Throughout scripture, we see God portraying Himself emotionally to His people (consider much of the prophets and Psalms and, of course, Jesus himself.) Now it could be, as some theologians have surmised, that God is merely accommodating himself to our limited human understanding – to communicate with us in a way we can understand. However, the sheer depth of emotion in these texts leans me away from this interpretation.

Rather, whilst affirming that humans cannot affect God’s nature in order to change who He is, I would affirm that being relational and feeling emotion towards His people is part of who God is. After all, He exists in a relational trinitarian form. I would not go so far as to say God has emotions in the same way we humans do. For example, although he can grieve (e.g. Ps 78:40–41), He cannot be overcome by this grief. And this grief is consistent with His holiness and love. He is always in control; His nature and character remain the same even while He interacts with His creation in time and space. He is not subject to human suffering (except as Jesus), but He meets us in it.

Therefore, I am comfortable with the idea that God would speak in a tone of grief at Abel’s death, a tone I hear frequently when I read scripture. He loved Abel and would have mourned Cain’s actions. However, I believe my Kayin was wrong in thinking he could actively ‘hurt’ God by killing Havel. God knew what was going to happen and would not have been taken by surprise. Besides, when he died, Havel went home!

Other versions of the story

Finally, the questions these chapters of scripture raise are not new. Indeed, the myriad forms of the story in Jewish, Catholic and Coptic tradition shows that it was often considered by our forefathers.

Several traditions claim that Cain and Abel were both twins and married their own twin sisters. I decided not to go down this route because if Abel had a wife, he would likely have had offspring, which he presumably didn’t, as Seth bore out his line (Gen. 4:25). Therefore, I left Kayin on his own for a while and made only Havel a twin, which fitted my narrative and characterisations. As the birth of women was rarely recorded in the Old Testament, a female twin being born with Havel is not unscriptural.

Some people suggest that, because they had perfect bodies in the Garden, it would have taken Adam and Eve little time to conceive, and therefore it is likely Cain was born in the Garden. I rejected this hypothesis for two reasons. Firstly, theologically, if a child was born pre-fall, then it would have been necessary for that child to directly sin and be banished from God’s presence, yet the Bible gives us no indication of this. Romans 5:12 is quite clear that sin entered the world through one man, and death through sin, “and so death spread to all men because all sinned.” Therefore, it was necessary for Cain to be born into sin after the judgement took place. This is also why I believe there was only one ‘first family’ (see also Gen. 3:20), although some maintain there could have been many.

Secondly, Seth was born when Adam was 130 years old (Gen. 5:3). Clearly, I agree with the traditional stories that other children were born between Abel and Seth (otherwise, who was Cain’s wife?) Yet, with perfect bodies, it is not likely that a great amount of time would have passed between the conceptions of these children. It is also probable, in my mind, that Adam did not lie with Eve in the Garden. Jesus tells us that in the resurrection, people will not marry (Matt 22:30, Mark 12:25, Luke 20:34–35.) In the presence of God, we do not need marriage, though we require fellowship. In Gen. 2, Eve is given as an ally (an ezer) to Adam, but the pronouncement in Gen. 2:24 is abstract from Adam’s situation (he had no father and mother to leave) so it does not necessitate that they were cleaved together in sexual union at that point in time.

Therefore, Cain is not conceived in my story until Adam is eighty years old (you need to read the next book in the series to figure this out.) The reason I give for this delay is envisaging a longer period spent in the Garden, rather than just a few days, and a great deal of wandering time after the banishment when the difficult relationship between Adam and Eve inhibits conception. When you consider what they say about each other before the LORD in Gen. 3, such difficulty is not inconceivable!

As I mentioned in the Author's Note, all these things are merely my opinion, and the story is not intended to add to the Bible. It is, if you like, a theological reflection on Genesis 4, in the form of fiction. Even if you disagree on anything above, I hope you were able to enjoy it.