Smile

On a darkening early December afternoon in 1946, I arrived from London at the Prague airport in a small passenger plane that flew on toward Warsaw, its ultimate destination. It was carrying journalists who worked for big wire services or newspapers, unlike myself, a stringer who was worth plane fare only as far as Prague. Toward midnight of that day, I would have to take a train the rest of the way to the Polish capital.

In the nearly empty airport, I saw a small neat-looking man with fair crimped hair who was evidently looking for me. We met; we shook hands. He was Jan. The gaze he fixed on me was steady and impassive; his lips were faintly widened in a half smile that didn’t leave his face during the hours I spent with him and his wife, Rose. Except when he was drinking tea, of course.

We took a bus to the city. At some point, I had an impression that his eyes were golden, but it was only a passing effect from the headlights of the one car we passed on the narrow road. I suppose his eyes were hazel.

He told me he had recently married Rose, an Englishwoman, who worked for a postwar refugee organization. It was she who welcomed me into their small flat in a building so cheaply and recently erected that it still smelled dankly of fresh plaster. She had made us tea, saying we must be frozen by that horrid wind that always sprang up toward the end of the day in the city of Prague. Beyond the two small windows of the living room, it was now black. She had bought a little cake and made a few coarse-looking sandwiches. “The bread,” she remarked, shrugging in a show of patient helplessness. Another thing to be borne as part of postwar life in Central Europe.

I had an impression she didn’t stop talking during the hours I spent in the flat, except when I interrupted her with questions of an ordinary sort. I didn’t care what she answered. I wanted to break the awful continuity of her bright, implacably cheerful voice that gave the same weight to whatever subject she brought up.

I knew so little, and the little I did know, I didn’t understand. My ravenous interest in those days was aroused by anything.

Jan watched Rose’s every move, the half smile fixed on his face. I slowly recognized in him an underlying desperation. Later, when we were on the trolley to the station, when he spoke to me of the fate of his family during the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia, I was unable to take in the meaning of his story except suddenly, and then for only a few seconds at a time. When I did, it was as though I grasped broken glass in my hand.

Rose’s avalanche of words slackened when she turned on their small radio, already tuned to an English news program. She sat down to listen. I realized she had been in constant motion since I’d arrived at the flat. Now she slipped her hands beneath her apron as though they were cold. I thought I could see her prominent knuckles through the thin cloth. But by then, it was time to leave.

Jan had pressed his cheek against hers when we arrived, and he did the same when we left. I turned away from them. The slow pressing of flesh against flesh was more intimate to me than a passionate kiss would have been.

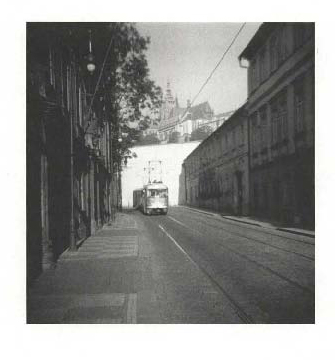

We walked several blocks in the shadowed gloom of Prague, the sidewalk lit fitfully by pools of light at the bottom of the few working streetlamps, until we heard the rumble of an approaching trolley. It halted for us, and we climbed up the narrow steps. Inside, a few women sat stolidly on slatted seats. Some stared at the floor; others looked out of dusty windows. One, wearing a babushka, fell asleep just as we passed the Charles Bridge.

Jan began to talk in a composed voice about his ten-year-old twin girls. I may have missed a few words because of the clamor of the trolley.

Annette Fournete/CORBIS

The twins had been taken to a camp run by Josef Mengele. Both had perished during something called an experiment by Dr. Mengele. Jan’s wife had died of starvation and despair in a concentration camp east of Prague. He himself had spent years in a different camp. No, he replied to my question, he wasn’t a Jew, only political.

He pressed my arm and nodded at a large building across the street. It was the railroad station.

There wasn’t any traffic as we crossed the broad street. In the dim station, I had a moment of fear and didn’t want to leave Jan’s side. He took my arm then and pressed me forward to the waiting train, its engine sending out white plumes of steam. As we stood at the foot of the black metal steps, he told me his second story.

“A professor I once knew,” he began, “had his whole family murdered by the Germans. One morning, I think it was a few days after the end of the occupation, he was staring from a window on the second floor of his house. He saw a German soldier running down the middle of the street. He ran down the stairs and out the door. The soldier was a few feet ahead, and the professor flung himself at him, catching his legs. The surprised soldier fell heavily to the pavement, knocking his head against a cobblestone. The professor looked up and saw an abandoned butcher shop, its windows smashed, its door gone. He carried the German into the shop and hung him by his neck from a meat hook, a very large hook intended for the carcass of a cow.”

I stared at him, holding my breath. He embraced me suddenly and said, “I hope you have an easy trip to Warsaw.”

I looked after him, but he didn’t turn as he made his way through the station.

As I walked up the steps and into the interior of the car, carrying my small suitcase, I thought about the smile that had not left his lips from the time I had met him at the airport and during his recounting of the stories I had just heard.

I had thought it was a grimace of pain and embittered amusement, more or less permanent. But as I settled onto a wooden seat, it came to me that it was a further punishment for the crimes that had been committed against him, that he should always be caught midway between raging laughter and lamentation.