Perlita

My great-uncle, Antonio de Carvajal, lived in a flat in a very old converted mansion on one of the broad avenues of Barcelona called ramblas. In the spring of 1947, I stopped working for Sir Andrew and left Paris to visit him. I had $100 with which to support myself for the month I hoped to stay in Spain, pay I’d saved from my job as a news-service stringer in Eastern Europe. It didn’t leave enough for traveling, but after nearly a year in postwar Europe I had become practiced in converting my few pounds into other currencies at the best rates of exchange.

This was offered by professional black marketeers as well as by people who had once been teachers, engineers, actors, and musicians, and others with now-useless vocations, who had been exploded out of their ordinary days by the war and were drifting through the cities of Europe, waiting on the edge of hopelessness for work permits that might enable them to resume some version of their former lives.

I remember the clothes they wore, garments of dispersion, dark threadbare jackets, pants often held up by string, their cold-reddened hands thrust into torn pockets as they stood for hours in all kinds of weather near banks and post offices where foreigners tended to gather.

As I boarded the train in Paris, I was too young and too dumb to worry about entering a fascist country; what I was apprehensive about were my meager funds. But two days after I arrived in Barcelona, I was put in touch with a man who gave me a good exchange rate of pesetas for pounds. (The bills had been printed in Leipzig, in Germany.) He was a Republican doctor who was not allowed to practice medicine by the Falange. He earned a living of sorts in the black market. During the week, he could be found in any one of several Barcelona cafés. On weekends he went to the mountains with dozens of vials of penicillin to serve as best he could the medical needs of those remaining Republican soldiers and their families who lived there in desperate conditions.

Tío Antonio was my grandmother Candelaria’s only surviving brother. I had spent a few years of my childhood with her in the United States and Cuba. Her brother was the only person she still corresponded with. I yearned to meet a relative who was a real European.

Tío Antonio was in his early seventies. He was a handsome benevolent-looking man with blue eyes and the large head of a Basque. Part of the northern branch of the family were Basques from Asturia.

The origin of the Basques is obscure. No connection has yet been found between their language and other European language groups. It is known that they antedate the ancient Iberian tribes of Spain and resisted the invasion of the Visigoths from the north with great stubbornness. That they were unable to resist entirely is proved by the prevalence of reddish- and fair-haired people in Spain’s northern provinces.

Luisa, Tío Antonio’s housekeeper and, sometime after the death of his wife, his companion, told me that he had once been redheaded. By the time I met him, he had a white tonsure like a monk’s.

IT WAS A VERY COLD SPRING, FOLLOWING WHAT WAS SAID TO have been the coldest winter in Europe for twenty years. A brazier of coals burned beneath the table where we often sat. From a wood chest, Tío Antonio took out his most valued books to show me. Some had been written by his friend, the Spanish philosopher Ortega y Gasset. As a young man, Tío Antonio had met with Ortega on many an afternoon, to drink thick Spanish chocolate in a café on one of the ramblas and to talk about Spanish Catholicism, politics, and life.

Tío Antonio had a small elderly dog; he could only guess at her age. He had seen her from his window. She was standing, apparently frozen with fear, among the railroad tracks that ran behind his building. Having just recovered from a severe pneumonia, he was extremely feeble and could barely walk. But with Luisa’s help, he descended the long staircase (there was a cage elevator that had not worked for years and was not working when I was there) and went out to the tracks where, after nearly an hour, he managed to coax the dog to come to him and then to carry her up to the flat. It was, he said, half a blessing that the trains ran so infrequently.

He named the dog Perlita, Little Pearl. She was a stiff-legged animal, white-furred except for a few mustard-colored patches. She had the look of a circus dog in an old engraving. She was not unfriendly but had an air of world weariness; she was a dog who had been through too much to be especially enthusiastic about anything in this life. But her gravity and oddly professional look were immensely appealing.

The cause of my great-uncle’s frailty at the time when he rescued Perlita was political and bitter. Several months before he saw the little dog among the railroad tracks, he had written a letter to my grandmother on Long Island to thank her for some sacks of sugar she had sent him for Luisa to exchange on the black market for food. He had a pension of sorts, but it did not go far in those straitened days, and a few pesetas and supplemental food eased life a little. In the letter, he expressed his hope that since Europe had been liberated from the Nazis, Spain too might be liberated from General Francisco Franco and his Falange. A young cousin from Cadiz was visiting him at the time. The same day he finished and mailed it, she went to a police station half a mile away and reported to an official there that her elderly cousin had written a treasonable letter to his sister in America.

The political branch took Tío Antonio to the police station, held him for nearly a week in a cold damp cell without a blanket to cover himself or a board to lie down on, and beat him, although not as severely as they might have a few years earlier when the power of the Axis would have inspired their blows with greater savagery. Now and then they gave him something to eat. He was an old man and the insult to his body was great, but there is more to being beaten than the suffering of the flesh.

He was a retired doctor. He had been a colonel in the army. He, like his friend Ortega, had written essays on philosophy, on Spanish history, and against the clergy. He told me about Miguel Primo de Rivera, the Spanish general whose dictatorship was established the year I was born and whose only good deed, Tío Antonio said, was to order that the horses ridden by picadors in bullfights be blanketed around their bellies to spare them from evisceration in the arena. He spoke of the monarchy, of Carlists, of Alcalá Zamora y Torres and his efforts to distribute church property, of Anarcho-Syndicalist rebellions in Catalonia, of Manuel Azaña and the Popular Front, and of Franco, always in terms of character: ignobility of spirit, malice, ambition, and human blindness, as though politics were no more and no less than direct aspects of human temperament. I understood that much, although the array of names and events bewildered me.

Luisa went to the police station each day he was there, taking food and warm clothing that was not given to him. And she was there that cold dusk when he was thrust out the door to faint in the street.

He was ill for a long time. It was during his convalescence that he saw the little dog and saved her.

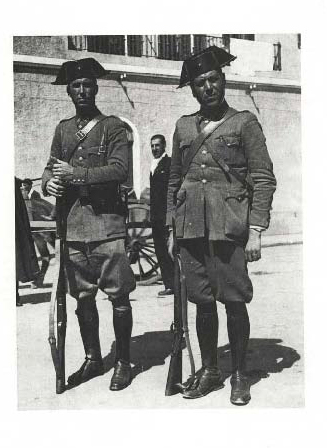

Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS

Perlita was such a strange creature. She would stand for a long time at the threshold of a room as though awaiting a sign. She was quite plump by the time I saw her. I asked him how he had fattened her up, for he had told me she was nothing but skin and bones when he rescued her.

“Sopa de ajo,” he answered, smiling.

Garlic soup.

When I lived with my grandmother in a small suburban village on Long Island, she occasionally sent me off to school in the morning with a breakfast somewhat different from cereal and toast. She minced cloves of garlic and spread them on a slice of dark bread that had been soaked in olive oil. On those mornings, my arrival at P.S. 99 was greeted by my schoolmates with cries of mock horror and hands stretched out to warn me not to come any closer.

I was the foreigner in a school whose population was made up largely, as I recall, of working-class Irish Catholics. The final damning evidence of my foreignness was my grandmother herself, when she came to school on those days set aside for parents to visit the classrooms.

She did not in the least resemble any of the other parents. She was much older, of course. She had a thick Spanish accent. She looked like a Spanish woman from northern Spain.

I loved the dark bread covered with cloves of garlic and soaked in olive oil, and I did not give it up.

Prejudice has its own headaches. I was a puzzle to the other children. I was fair-haired and might have been taken for a Scandinavian. One branch of my family in southern Spain was descended from the Emirate of Granada. If the other children had known I had Arab ancestors from North Africa, they might have been entirely floored or chased me out of the school. As it was, they didn’t know what to do with me. They settled for halfway measures, allowing themselves to torment me from time to time, becoming friendly when they forgot—as children will—what it was exactly they were tormenting me for. Toward the end of my time at the school, their attention was diverted from me by the arrival of two boys, also “foreigners,” an Armenian and a French-Canadian whose accent was as heavy as my grandmother’s. The three of us soon contrived a small country of our own.

When Tío Antonio told me what he had fed the starved Perlita, I recalled in one intense moment those puzzling, painful schooldays of mine. I looked at Perlita with a sense of comradeship. Garlic had saved her. In a way it had saved me too, confirming my position as an outsider and preventing me from absorbing easily any unquestioning assumptions of national superiority, so prevalent, so grotesque a phenomenon in our country, made up as it was and is, in large part, of transportees, captives, and immigrants.

When I think of Spain, I imagine my great-uncle sitting at the table, its wood warm from the heat of the coals in the brazier, Miguel de Unamuno’s The Tragic Sense of Life open before him to the pages from which he is reading aloud to me, and Perlita standing quietly near him. After a while, she seems to feel it’s safe to lie down, her back a few inches from the brazier, and a few minutes later she sleeps.

Underwood & Underwood/CORBIS

I see the great black stones of the police station. I did go look at it. A man emerged from the building as I stood there. He was wearing a thin white raincoat, which I had learned all policemen wore who worked in the political branch. Fashions, I saw, existed also among fascist police.

He said something to me with a smile that meant he thought I was from Asturias. I felt a fleeting pleasure in that—not to be thought a foreigner. When I reluctantly shook my head, he asked me if I was English. I told him I was from the United States. He said, “I suppose you think we eat babies over here.” I did, but I didn’t say so.

I think of what is called political life, so abstract until a cane is laid across one’s back. I think of the life of the spirit that would send a sick old man out to rescue a stray animal he had glimpsed on the railroad tracks. And I think of the civil wars, of the young cousin from Cadiz and her cruel act, licensed by ideology, and of the degradation and, finally, destruction of family and fellow feeling.

But what I see most vividly now, six decades later, is Perlita, saved!

As I look at her in my mind’s eye, I am reminded not of the loftiness or dignity of the human spirit but, rather, its sudden capacity in dire circumstances for an overarching sympathy, its redemptive humbleness.