Astronomy Lesson

One early evening I borrowed a station wagon from a social worker at Sleepy Hollow, an institution in Dobbs Ferry, New York. Seven adolescent boys hurled themselves into the seats, yelling, shouting, hitting, laughing. When I got in the driver’s seat, they all calmed down somewhat. It was in the mid-1950s.

I had gotten the job as tutor through a friend. Sleepy Hollow was partly administered by the Manhattan School Authority; it was nondenominational. Most of the children were troubled and lived in cottages with an adult married couple. During the day they saw social workers. Some of them went out to the local public schools; half did not. They were defined as too antisocial by the psychiatrist who visited monthly.

They ranged in age from eleven to seventeen. They were immensely excited that evening—getting away from the institution—and seemed to me to find even breathing a new sensation. They had all been brutalized when they were younger: incest, beatings, desertion, and—in one case, Jimmy’s—left as an infant in a garbage dump. Another boy, the oldest, Frank, was black. He was tall and thin, quick on his feet, and, as he said about himself, made for basketball. But he didn’t care for sports. What he was interested in was outer space. It was largely for him that I had made an arrangement with Dr. Lloyd Motz, the astronomy professor at Columbia University, to use their telescope on the roof of a building named Pupin. That was where we were headed that night.

Frank had spent most of his life in foster homes. He had a rootless quality; he always seemed on the point of departure. He perched on the edge of his desk and listened tolerantly while I tried to show him what a complete sentence was, but he was thinking of something else.

Someone had told me Frank was a sociopath, but I had difficulty attaching that word to him. He loved the talking part of my evenings at Sleepy Hollow, after the work was done in arithmetic or spelling or composition: the stories, the jokes we made, the tides of spoken memories.

I saw him angry only once. That was when the institution children, himself among them, went out to neighborhood schools, having been issued special food tickets because, it was said, they frequently spent the money they were allotted for lunch on cigarettes and candy. The local kids did too. Drugs were rarely available in those days.

Frank and the other children refused to go to school until the administration stopped the use of the food tickets. It was hard enough on them to be known as institution inmates, but to be so dramatically singled out as they were at the moment when they had to hand over their maroon tickets to the cafeteria cashier was intolerable to them. They were often bullied and baited by the local children, who exalted themselves and their own circumstances—whatever those might have really been—at the expense of the strangers in their midst, a form of cruelty not restricted to children.

When Frank was seven, he had asked his mother to take him to a movie. She said she couldn’t; a friend was driving her to an appointment with a doctor. Frank told her he wished she was dead. She was killed in an automobile accident that afternoon, although the driver, her friend, was not seriously hurt. Frank’s father had deserted his family several years earlier. There was no one to take care of Frank. He began his institutional life a few weeks after his mother had been killed.

I don’t know how deeply, or in what part of his mind, he felt there was a fatal connection between his fleeting rage, the wish he had expressed that his mother die, and her death later that day. I know he suffered. His very abstraction was a form of suffering.

One night Frank lingered at the gatehouse where I held my classes. He asked me if I had ever been in another place like Sleepy Hollow. I said yes, once. Then for some reason I told him about the concentration-camp children I had met ten years earlier in the high Tatra Mountains in Poland. I spoke a little about the Holocaust. We were sitting on a step. It was a clear night in spring, with a little warmth in the air. The stars were thick.

“I never heard anything like that,” he said. He asked me what had happened to those children in the mountains. I said I didn’t know, except what happens to everyone—they would have their lives, they had endured and survived the horror of the camps, and each would make what he or she could of life. He looked up at the sky.

“What’s after the stars?” he asked. “What’s outside of all we’re looking at?”

I named a few constellations I thought I recognized. Although his school grades were low, he’d read an astronomy textbook on his own. He corrected my star guesses twice. “But what do you think about way past out there?” he urged.

I said there seemed to be a wall in the mind beyond which one couldn’t go on imagining infinity—at least, I couldn’t. “Me neither,” he said.

We sat for a few more minutes, then said good night and walked away from the gatehouse, me to my car and he to the cottage where he would live a few months longer before he ran away and was not heard from again.

The children in that residence accepted a certain amount of discipline—do your homework, eat the carrots before the cupcake—though they complained noisily. What they really hated was to be told how and what they were. They had heightened sensitivities to questions that were not questions but sprang from iron-clad assumptions about them and their troubles.

There were many people on the staff who were sure they knew everything. They had forgotten—if they had ever known—that answers are rarely synonymous with truth.

Those staff members were imprisoned in their notions as much as the children they met with weekly were prisoners of case-history terminology. Each profession requires a system of reference and language to express it, but the cost to truth is high if there is no reflection of other possibilities beyond their systems of judgment.

“What’s outside of all we’re looking at?” Frank had asked.

Driving the station wagon to Columbia University that evening, I was hoping the telescope might show a thing or two.

I’d not been there myself. Dr. Motz had advised me that the atmosphere in New York City was so filthy we would be lucky if we glimpsed Venus. Columbia owned another viewing telescope in South Africa where, of course, astronomers had better visibility. As I parked on Broadway, the boys had begun to sing raucously, except for Frank, who told me later that he had been sweating with excitement.

I led my group to the Pupin building at the north end of the campus, where we took an elevator to the top. Duckboards covered the tar roof and the gravel scattered over it. All around us were twinkling city lights, like stars. The wind was blowing so hard it was difficult to open the door. The boys whooped as they clustered around the entrance.

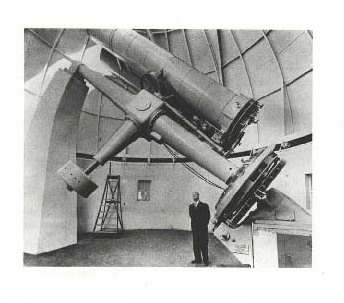

Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS

Inside was the assistant to Dr. Motz, who’d been told we were coming. An enormous slice of the sky—it was clear that night, as clear as it could be in New York City—was visible in the domed roof far above us. A curved metal section had been retracted, and the huge telescope was aimed through it at space. The assistant looked through the eyepiece on one side of the telescope and adjusted it for what seemed an hour; then he gestured to me to look. The boys were silent as they stood behind me in the dimly lit room. On their own, they had formed a small line.

I looked and saw at once a rose-colored pulsating marshmallow—water vapor, the assistant explained—that was the planet Venus. Then I saw the rings of Saturn, tides of gases, a myriad of star clusters and, close up, the sweet moon, pitted with craters and reassuring in all that vastness. It was as though I had swung through space on a swing whose ropes extended from unimaginable depths of the darkness all around.

I stepped back and motioned the boys forward, one by one. Frank was last, and he spent the longest time looking through the eyepiece.

It took more than an hour. Then we went back over the duckboards and down the elevator. The boys didn’t speak on the drive back to Sleepy Hollow. I heard someone sigh.

It took me a few days to understand their silence that night. I had imagined, at first, that it was because they had seen things that were larger than themselves, that gave them new perspectives on their lives, on everyone’s life—the usual sentimental relativism.

But now I think they were quiet because for the first time, in the observatory at Columbia, they had seen something other than themselves.

I too had had that experience ten years earlier. The Second World War had caused devastation all over Europe, and millions upon millions of people had been slaughtered, yet my year over there had shown me something beyond my own life, freeing me from chains I hadn’t known were holding me, showing me something other than myself.