The Vedic Civilisation succeeded the Indus Valley Civilisation in ancient India, but there is conflicting historical evidence about its origins. One theory points to the migration of Indo-European tribes, possibly from Central Asia, Iran, Scandinavia or Russia, into northern India in 2000 bc. These nomadic tribals, known as Aryans, mingled with the Dravidians from the Indus Valley and eventually established what came to be known as the Vedic Civilisation. It was spread across the Sapta Sindhu (Seven Rivers) region, in the present-day Indian states of Haryana and Punjab.

The ancient Hindu scriptures, the Vedas, dated between 1500 bc and 800 bc, provide extensive details of the Vedic Civilisation: The Rig-Veda, the earliest document of Indian history, gives a comprehensive account of life in the early days of the Aryan society, while later works such as the Sama-Veda, Yajur-Veda and Atharva-Veda provide details about the subsequent years. The Vedas were composed in the Sanskrit language, and the Vedic Civilisation takes its name from these ancient scriptures. The great Indian epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, are also believed to have originated during this period of Indian history. The Vedic age is divided into the Early Vedic Period (1700 bc–1000 bc) and the Later Vedic Period (1000 bc–500 bc).

The Aryans were tall and fair in appearance. They organised their community into small tribal units called jana, with chiefs (sabha) and ruling councils (samiti). The jana was further divided into smaller segments called vish and grama. There were several janas, and they fought amongst each other for cattle and land. The janas developed into janapadas, small kingdoms with a supreme chief, the raja or king, who commanded the army. The king was assisted by the senani (army chief) and the purohita (chaplain), who took on the role of a medicine man, curing diseases with the use of incantation.

The Aryans had a primitive nomadic culture and did not have knowledge of sophisticated urban planning as seen in the Indus period. Rather, their houses were simple structures built of mud. However, like the Indus people, the Aryans were skilled in making bronze utensils and weapons. Their main occupation was cattle rearing and agriculture. Cattle were highly valued and used as a medium of exchange in the barter system. The people also bred sheep, goats and horses, using the latter for their war chariots. Spinning, weaving and carpentry were other common trades.

The Aryans had a patriarchal society, with the father regarded as the head of the family and the mother occupying an inferior position. Monogamy was widely practised, and sons were coveted because the family heritage passed from father to son. It was during the Vedic period that India’s infamous caste system (varna) was born. Society was divided into separate classes based on occupation: the priests, known as Brahmins, were the dominant class and wielded the most power; the ruling and fighting classes were called Kshatriyas; traders and merchants were classified as Vaishyas and the labourers were known as the Shudras. Social distinctions became increasingly rigid and the classes developed into hereditary castes, with restrictions placed on intermarriage.

The religious consciousness of the Aryans was highly developed, although they did not pray at temples or worship images. Their rituals consisted of burning fires at home, singing hymns to the gods, making offerings such as rice and milk and sacrificing animals. The Aryan gods included Varuna (Thunder), Surya (Sun), Agni (Fire), Vayu (Wind) and Usha (Dawn).

Brahma AND The Caste System

According to popular belief, the four varnas were created from different parts of Brahma, the creator. The Brahmins were created from his mouth, the Kshatriyas from his hands, the Vaishyas from his thighs and the Shudras from his feet.

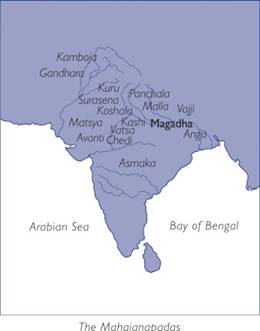

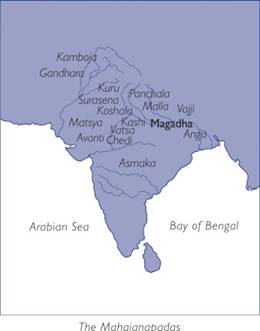

In the Later Vedic Civilisation, agriculture became the main economic activity of the people while cattle rearing declined. Popular crafts developed into vocations and goldsmiths, ironsmiths and carpenters came to the fore; iron, especially, became a commonly used metal during this period. Another change was the merging of the numerous small kingdoms or janapadas to create 16 large ones known as the mahajanapadas or great kingdoms. This period also saw progress in political and economic organisation, with a tight-knit monarchy replacing the earlier tribal rule. Power moved from the rural to the urban centres where noblemen usurped positions of authority. Strides were made in religious thought too, with ideas from a new Hindu culture taking root. The Aryans used the Vedic Sanskrit language up to the 6th century bc, when their culture gradually began to shift to Brahmanism, an early form of Hinduism. This marked the end of the Vedic Civilisation.

Laws Of Manu

The Brahmins, the most learned sect, laid down rules and regulations, customs, laws and rites for the rest of society in manuals called the Dharma-shastras. Of these the most ancient and most famous is the Manava Dharma-shastra (Laws of Manu), belonging to the ancient Manava Vedic school. The Laws of Manu comprises of 2,684 verses and deals with the norms of domestic, social and religious life in India.

Magadha was among the most powerful of the 16 Aryan kingdoms known as the mahajanapadas. It was also in Magadha where the religions of Buddhism and Jainism flourished in ancient times, posing a threat to the existing Brahmanism. Magadha was situated in north India, in modern-day Bihar and Jharkhand. Its capital was originally Rajagriha (now Rajgir) and later shifted to Pataliputra (now Patna). The kingdom gained prominence under the rule of Bimbisara (543 bc–491 bc), who was a contemporary and staunch supporter of the Buddha, the founder of Buddhism. Rajgir is considered a sacred site in Buddhism as the Buddha spent many years preaching there, delivering his sermons in Magadhi, the language of Magadha and a dialect of Sanskrit. In fact, the city was the venue of the first Buddhist council held in 486 bc, after the Buddha’s passing. The third Buddhist council was held at Pataliputra under the auspices of Emperor Ashoka of the Maurya dynasty. Besides the political and religious developments, Magadha and other kingdoms in northern India also witnessed a growth in agriculture between the 6th and 5th centuries bc.

There was also considerable progress in commerce during this period.

It was under King Bimbisara (543 bc–491 bc), who belonged to the Shishunaga dynasty, and later his son Ajatashatru, that Magadha achieved greatness. Bimbisara extended the empire by annexing the kingdom of Anga, now West Bengal, in the east. Ajatashatru, who was responsible for his father’s death, continued the expansion and built a fortress at Pataliputra during his war with the Licchavi republic. The expansionist Shishunaga dynasty was overthrown by the Nandas in 343 bc. The Nanda dynasty, founded by Mahapadma, ruled Magadha until 321 bc. when it fell to Chandragupta who made it the centre of his Maurya Empire. Later, in the 4th century ad, Magadha rose to prominence once again during the Gupta period.

Horse Sacrifice

A popular royal ritual was the horse

sacrifice or Ashwamedha Yagna. In this ritual, the king’s horse, accompanied by

warriors, was set free and allowed to go where it pleased for a full year.

The territories covered by the horse during this period then came under the

control of the king, with the warriors stepping in to enforce the king’s claim

of sovereignty in the case of opposition from the local inhabitants. The horse

was slaughtered at the end of the ritual.